14,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

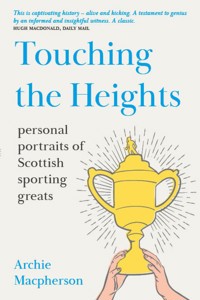

They all excited and inspired me by how they fought their corners […] So I want to place them all round a fantasy dinner-table, not just to dine, but to relive how I saw them in action and how much they had in common. Who would be on your dream dinner party guest list? Over his 50 years in broadcasting, Archie Macpherson has seen many sports personalities come and go; in Touching the Heights he collects the 13 who have inspired him most around his fantasy dinner table. Some are well-known, others less so, but all shaped both their sport and those, like Macpherson, who watched their careers unfold. Tommy Docherty · Jackie Paterson · Jim Baxter Eric Brown · Jimmy Johnstone · Sandra Whittaker Dr Richard Budgett · Ally MacLeod · Jock Stein · Sir Alex Ferguson · Bill McLaren · Jim MacLean · Graeme Souness From football to golf, boxing to athletics, Touching the Heights celebrates the breadth of Scottish sporting achievement. Whether telling the tale of a boy who acquired new shoes by stealing them from the local baths, or that of a distinguished medical scientist at the centre of sporting transgender debates, one thing unites them all: Without them life would have been much poorer.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 419

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

ARCHIE MACPHERSON was born and raised in Shettleston in the east-end of Glasgow. He was headteacher of Swinton School, Lanarkshire, before he began his broadcasting career at the BBC in 1962. It was here that he became the principal commentator and presenter on Sportscene. He has since worked with STV, Eurosport, Talksport, Radio Clyde and Setanta. He has commentated on various key sporting events including 3 Olympic Games and 6 FIFA World Cups. In 2005 he received a Scottish BAFTA for special contribution to Scottish broadcasting and was inducted into Scottish football’s Hall of Fame in 2017.

First published 2022

ISBN: 978-1-80425-054-9

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 11 point Sabon by Lapiz

© Archie Macpherson 2022

To Pat Woods, my researcher, who through the decades has been a constant source of inspiration.

Contents

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER 1The Bowery Boy

CHAPTER 2The Punch

CHAPTER 3The Left Foot

CHAPTER 4The Bomber

CHAPTER 5Il Topolino

CHAPTER 6One-Hundredth Of A Second

CHAPTER 7Stormy Waters

CHAPTER 8Pipe Dreams

CHAPTER 9The Aberdeen Rose Bowl

CHAPTER 10The Hawick Troubadour

CHAPTER 11The Wise Man From The East

CHAPTER 12The Odd Couple

CHAPTER 13The Coal Face

Acknowledgements

I WOULD LIKE to thank Dr Gerry Hassan for his overall critique of my manuscript and I am grateful to the BBC’S Tom English and John Beattie for their evaluations of segments of the book. Tommy Gilmour, former boxing promoter, guided me carefully as I ventured into his sport, as did former Ryder Cup player Bernard Gallagher in pursuance of Eric Brown on to the links. I am indebted to Lara Scott, assistant editor of the Daily Record picture desk for her assistance in providing the photographs from the newspaper’s archives. I was rightly kept in line throughout by the meticulous care of my editor Kira Dowie. As the book is also a product of the time of the Coronavirus lockdown, I hold AstraZeneca in awe for keeping the wolf from the door.

Prologue

FRIDAY AFTERNOON WAS that magical time I have always associated with the emergence of the Scottish hero. Just after two o’clock, on those days, our teacher in the primary school in the east end of Glasgow, Miss Paton, would tell us to sit back, put everything away and just listen. She would leave her desk and sit in a chair in the middle of the floor in front of us, to remould herself as storyteller, distinct from the strict martinet she damn well was. One day she told us a tale from this russet-coloured book about Eric Liddell and the Olympic Games in Paris in 1924. It thrilled and puzzled me. His strict Christian beliefs prevented him from running in the 100 metres heat on a Sunday, for which he was favourite, and instead he won the 400 metres gold on a weekday. It was difficult to grasp. I could understand the likes of shunning football in the backcourt to attend bible class on the Sabbath, but tossing away the chance to win the coveted Blue Riband event and the honour associated with it, was a sacrifice that was beyond the comprehension of a ten-year-old.

It was not until decades later in 1970 that I fully grasped the effect Miss Paton’s story was to have on me. It was during the Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh. Fortune had smiled benevolently on me. For in the BBC’S Games office, in the media centre in Edinburgh, my desk was only feet away from that of the great Harold Abrahams, then a BBC athletics pundit. As anybody who has seen Chariots of Fire will know, Abrahams won the 100 metres gold in 1924, principally because the British record holder for that distance, Eric Liddell, had refused to compete.

Thinking back to the day I first heard Liddell’s story in that classroom, I was in awe of this old man sitting near me. Then aged 71, he commanded respect from everyone and from his desk he intoned, like a cardinal, about athletics; his statistics sounding as if they had been plucked from the Old Testament. But, in fact, he also turned out to be a cantankerous old bugger, breaking hardly a smile in all the time I was in his presence and clearly not suffering fools gladly with his waspish delivery to all and sundry. And as a result, for a fledgling like myself in broadcasting then, he had become virtually unapproachable. When I recounted my disappointment to the superb BBC radio commentator Welshman Peter Jones, he was at pains to alert me to the disappointments the great runner had suffered in later years and that at heart, Abrahams was a romantic, as portrayed by Ben Cross in the film. For hadn’t he taken a sliver of gold from the medal he had won, almost certainly because of Liddell’s absence and converted it into a wedding ring for his betrothed? And then had not both medal and ring subsequently been stolen from his home? It was a kind of precis of the collapse of his fortunes. It didn’t ease my discomfort though at being so close to his hovering truculence and I assumed that had I brought Liddell into the conversation Abrahams would have barked my head off. Admittedly, I was something of a faint heart then, so I learned nothing of that tumultuous time of Paris 1924 from that iconic figure. And, in any case, weighing heavily on me was the feeling that it was not the occasion for reflection and analysis of the past, amidst the helter-skelter of reporting on the Games, so eventually I was swallowed up in pursuit of other events. I still regret that.

But it was then I realised I was in debt to Miss Paton. For she had brought a sportsman into the classroom where previously her history stories were about kings and queens, knights and battles. She had given sports its proper place in the forefront of our appreciation of the past. So I can claim to trace my sports zealotry back to the Liddell story and of the mission I found myself following, of convincing people of how vital the battles in sports arenas were in shaping society’s character, and lending us safety valves to ventilate deep-rooted feelings. It has never been easy. For instance, I used to relish coming across some hugely buttoned-up administrative BBC mandarin who would affect a disdainful air when you associated yourself with sport, clearly regarding it as waste of anybody’s time. Then suddenly, from the depths of their subconscious they might utter, ‘The ball’s in their court’; or ‘it’s par for the course’; or, as the executive said to me just as I was leaving the BBC, ‘You’ve had a good innings’; and as a reflection of the kind of political scene in the last decade, ‘They’re moving the goalposts’. All as if sport had slipped under their radar, triumphantly embedding itself in their language. They certainly were indifferent to my acceptance of George Orwell’s assessment of sport as being, ‘...war without the shooting.’ It reached a peak of callousness for me in 1971 in a discussion about the Ibrox disaster, when 66 people, including some kids, were killed in a staircase accident, and Pat Walker, a BBC executive asserted to me, ‘66 out of 80,000. Not all that many.’ A mining disaster of that dimension would have provoked a different sort of response.

But progress was made. Not long after that I proposed to BBC Scotland’s new flagship news programme, Reporting Scotland, that they should establish a regular Friday evening sports bulletin and weekend preview when, at that time, sport was barely mentioned in news except when some football personality transgressed the law of the land. The almost dismissive resistance to that idea was such that I became painfully aware of how a suffragette must have felt in fighting for the vote. Then along came a new tough but progressive news editor in George Sinclair who was a regular attender at Scottish football, saw the light and thus was born the Friday night sport niche, the kind of which is seen on any news channel in the land now. Of course, my main passion was football which figured heavily in that preview. But I was also occasionally unfaithful to it and strayed. I found myself courting boxing, athletics, golf and even rugby personalities, as will be seen in this narrative. They all excited and inspired me by how they fought their corners in their private lives and taught me something about how to survive in their harshly competitive world. Some well known, others less so. Certainly their stories of sporting excellence would have been fit for that Friday afternoon story-time spot, given that Eric Liddell had paved the way for them. So I want to place them all round a fantasy dinner table, not just to dine, but to relive how I saw them in action and how much they had in common. I suppose some would end up throwing bread-rolls at one another, or at me, and certainly a few would end up legless under that table. I would recount their stories to prove how much they had in common.

My first invite would be to the man who grew up near me, ate from the same fish and chip shops, swam in the same baths, clambered along similar backcourt dykes, played on the same ash pitches and, as life proved, certainly did not squander those character-building pursuits.

CHAPTER 1

The Bowery Boy

THE DOC STRODE into the BBC building, in 1971, with a smile on his face, armed with a ready quip about the lah-de-dah folk of Glasgow’s west end around Queen Margaret Drive, sat back in a chair like he had staked it forever and then proceeded to hold the Corporation to ransom. He had arrived for an interview. You felt instantly that Tommy Docherty was playing a role on a stage to a wider audience than merely the handful around him in the BBC sports office. A seismic change was about to take place in the humdrum normality of that setting which ran daily on the principle that nothing ever changes much. It was about to. For without further ado he asked a question.

‘How much am I getting for this?’

It had the nonchalance of a man asking for a cup of tea, but a silence immediately fell over an office containing several producers, a scattering of secretaries and a television presenter, all of whom had never heard that sentence uttered in their presence before. In that office where money and contracts were never mentioned, it had the effect of someone farting openly and loudly without any apology. All this was accentuated by the fact that nobody there could answer that question. He then made it clear that he would not be doing any interview, unless he knew what we were crossing his palm with. No hostility in his voice, no aggression. It was going to be a friendly stand-off, because nobody really knew what to do next. Anybody in the media business would have known that all this should have been arranged in advance by somebody somewhere, even someone in that office, except for the fact that the BBC was quite unlike any other business. His request would have to go through various strata of bureaucracy, with an added complication that the interview I was about to conduct with him would be used by our colleagues in London on one of their network programmes, so the cross-border political question would have to be thrashed out as to who was actually going to pay for his presence. Of course, we were hoping the lords of the manor in London would stump up whatever the fee was likely to be. In any national issue, major or minor, we in BBC Scotland always played the subordinate role.

I knew this would take some time, as one of the producers set off to tackle this problem with a look on his face of a man asked to find the source of the Amazon. Meanwhile the Doc sat there and flicked over a newspaper, humming and whistling, awaiting the outcome of our tackling the labyrinthine BBC accountancy system. Our colleagues in London were interested, simply because the Doc was popular in England, particularly throughout the media, where he was seen as a sure antidote to bland clichés. After all, in his interview with Chelsea directors for the managerial post, he admitted afterwards to the press, in referring to Vic Buckingham, the other man in consideration, ‘If I get the job you’ll get a coach. With the other man you’ll get a hearse!’ His tongue was quicker than that of the lizard. He had been in the south since 1949 having only played senior football for two years in Scotland with Celtic, where on his debut they lost 1–0 to Rangers. Then he moved on to Preston North End. But what really caught their imagination in the south was his management of Chelsea, right in the heart of the metropolis, where they could boast of support from a wide array of public personalities, including many from the entertainment business – like the late Hollywood actor Steve McQueen, Tom Courtenay, Tommy Steele or the late Sir Richard Attenborough who became obsessed with the club after being allowed to train there for his demanding role as Pinky in the film Brighton Rock. Ultimately he was to become a director of the club at the time the Doc was manager. That glitzy decor suited the Doc with his ability to reach out to the media as if he were part of showbiz himself. After leaving Chelsea he had drifted to four other clubs before accepting an interim provisional two-match post as Scotland manager, in September 1971, when he was holding a minor assistant manager’s job with Hull City. Throughout though, he still carried that confident swagger that was a combination of the Glesca ‘fancy-your-chances-then-big-man?’ confidence and the cosmopolitan ease he had soaked up on his travels. All that was irresistible to the media.

On the assumption that somebody would cough up enough to satisfy the new Scotland man I sat alone with him, the sun shining strongly through the window, in keeping with his sunny, cheery disposition of non-compliance. It was then I decided to play my trump card.

‘I was born in Shettleston,’ I told him. ‘771 Shettleston Road. Above a Tally’s. Billiard hall just round the corner. Palaceum cinema just across the road.’

He located that immediately. He put down his newspaper and I knew that the familiarity of that geography had slipped through his guard. There was a popular belief, which I think still exists, that he had been born and brought up in the Gorbals area of Glasgow which, since its generational association with deprivation and squalor, suited the dramatisation of his rise to fame. In fact, his family left the Gorbals before he could walk and he lived in the east end right up to his teens, only half-a-mile away from where I was born in Shettleston. He certainly did not have an easy life there. He told the Daily Telegraph once,

If you wanted a new pair of shoes you went down the swimming baths in bare feet and just nicked a pair. I didn’t think it was morally wrong. It was the thing to do.

His lamp-lighting mother Georgina, who brought up her family in dire straits, recounted to Jack Webster the writer and journalist in 1971, on the week the Doc accepted the Scotland job, of a compassion that never left him from childhood. She had come home one night and found a strange boy sleeping in the family bed. The Doc had found him in an air-raid shelter and said to his mother, ‘Ma, we cannae leave the wee sowl sleepin’ out in that damp shelter.’ Georgina and the Doc cared for him for the next ten years.

But all of that was not in the Gorbals. It was in that area of Shettleston streets we called the Bowery. Nobody knows why it was thus named, although the strong suspicion was that it was to mirror the rough, tough neighbourhood that was pictured in the highly popular Hollywood series, The Bowery Boys. Unsurprisingly we identified a lot with American cinema. Because of that lurid reputation, we always gave the streets around his home a wide berth, since tribal affiliations could sometimes lead to combat, which was not always unarmed. The Doc though, was proud of where he was brought up and especially of our mutual love of the first club he played for, Shettleston Juniors. That day, as he sat waiting for some princely sum to come his way, he suddenly became more contemplative when I informed him that in 1947 I saw him making his debut for Shettleston, or the ‘Town’, as it was called in junior circles.

Standing in the crowd I heard the first sounds of ‘C’mon, Doc!’ being shouted from the small but packed terracing to the right-hand side of the pavilion, where stood a phalanx of blinkered men who introduced me to an appealing variety of inventive curses that I kept in store, and effectively used, in later years. They were also men who could tell the quality of a player in his first couple of touches on the ball and knew he was a class above the rest. But it was not that the Doc, playing there for the first time, was a stranger to many of them. In a close-knit community they would have known about his qualities from the days he would have been watched from the windows of the tenements playing in the backcourts, before graduating to the likes of amateur football on Shettleston Hill pitches where Corinthian values were scarce and crowd invasions were hardly rare. He was no longer a fledgling, but a bona fide Shettlestonian by wearing the white jersey of the Town which I always considered to be the shirt of neutrality, given the strong Celtic and Rangers sectarian identities which permeated the entire east end. Of course, the others who were playing for the Town around that time made him look like a young prince. One player seemed to typify the loveable peculiarities which surfaced at junior level. Doc McManus was his name. He came from the distinctive tradition of Scottish inside forward play, owing much to stunted growth, a fondness for the bevvy, a disdain of sprinting any more than six yards and a body swerve in which the heavily endowed backside and torso seemed to part company for a fraction of a second. But loveable, for all those reasons, because he could also bewilder the opposition. Others around him there had less subtlety and would have put the boot into a begging infant if required.

It is not that junior football did not excel in many ways and could produce great players in those days. It drew big crowds. In the immediate post-war years there was a hunger for the game at that level because it nurtured local identities, was relatively cheap and convenient to the workplace. I used to see men, having come straight from work in the bottle-works adjacent to the Town’s ground, Greenfield Park; maybe having a quick pint; putting a bet on with the illegal bookie, hidden in a close somewhere; and then queuing up to get into the match in their dungarees. The smell of sweat and the pungent odour of their working clothes wafts towards me again even as I write this.

The Doc was not part of that scene very long. Only six games later he left to go to his beloved Celtic. The affection for that club, and his identity with the upbringing that was deeply influenced by St Mark’s Catholic School just off Shettleston Road, clung to him for the rest of his life. Although, he couldn’t supress his natural irreverence about anything, so long as it made people laugh. I recall sitting beside him at the top table of a dinner he was speaking at in a Glasgow hotel when, during his hilarious speech, he quipped about his religion, ‘I was a Catholic until I watched The Thorn Birds’, referring to the TV series that portrayed illicit love between a priest and his married lover. Nothing escaped his wit, which was honed around the streets of the Bowery where a quick mouth earned you respect. It was no surprise then that he could always refer back to his childhood with ease as if it were only yesterday.

With all of that in his background it is certainly true that the pull of his native land had something to do with him accepting the Scottish managerial post. Here was a feisty fighter from the Bowery who joined Chelsea as manager when they were in dire straits and heading for relegation. He could not save them from that fate, but steered them to promotion in the next season and then went on to win the League Cup in 1965. Playing attractive attacking football which earned his team the name ‘Docherty’s Diamonds’, they went on, in the following two years, to reach two FA finals as runners-up and reached the European Fairs Cup semi-final. More than a reasonable record for a native son. But he was always restless and sometimes stubborn to a fault.

His downfall at Chelsea, for instance, can be traced back to the night in Blackpool when eight players broke a night-time curfew before the match, including the revered Terry Venables. The Doc sent them packing back to London on a train the following morning, and with his virtual reserve team resultingly defeated 6–2, their chances of the English League title had disappeared. Even some of his admirers were critical of that reaction, given that the players had been cooped up in a hotel for a solid week in advance of the League game and that he had misjudged their mood. It began a chain of events which saw increasing hostility between himself and his board, until he simply walked out on them in 1967 – to the alarm of many supporters, one of whom paid for a death notice in the Times, ‘In memoriam. Chelsea FC, which died Oct 6 1967, after 5 proud and glorious years.’

He was assistant manager for Hull City in 1971 when the emergency call came from the SFA to become caretaker manager replacing Bobby Brown who, after a glorious start to his reign in 1967 by beating the World Champions England at Wembley in 1967, 3–2, had suffered seven defeats and one draw in his last eight games. On the Doc’s temporary appointment on 12 September 1971 the Glasgow Herald reflected the mood of the entire media when they described the Doc as ‘the 42-year-old fiercely partisan Scot’. The rest of the media immediately played up his fiery, cross nature with little scrutiny of that other restless, ambitious side of him and most certainly, his relationships with various football directors, some of whom he was not slow to call ‘parasites’ to their faces. On top of that some people could not stomach his breathtaking candour. When, for instance the Chelsea director Mr Pratt, who was eventually to become chairman, clearly irked by the Scot’s cockiness, asked him in exasperation, ‘Is there anything you’re not good at?’ The Doc instantly replied, ‘Failure!’ Pratt could not grasp the instinctive irreverence of the Bowery Boy whose quips could flatten any ego, and eventually they were to clash dramatically on the eve of his departure from Chelsea.

When the SFA decided to opt for him as interim manager and put him effectively on trial for two games, they were in desperate straits and were banking on his personal popularity to lift spirits all round. They paid scant attention to the fact that he had been a wanderer – four clubs since leaving Chelsea – and I was not alone in thinking that whatever happened back among his ain folk that this post was not his ultimate ambition. It was the immediate future though that was in everyone’s mind as 58,612 hopefuls turned up for his first challenge against Portugal at Hampden on 13 October 1971. Something exceptional occurred in that game which could have made you believe it was manufactured by some mystical force to reflect the personality of the man in the dugout. Scotland had gone into the lead through John O’Hare in the 23rd minute, as the product of an overall brisk, aggressive performance that was enthusing the crowd. However, we were in cautionary mood at half-time. Then came a remarkable period of play. Portugal equalised in the 57th minute from Rodrigues. His free-kick bent round the wall, wrong-footed goalkeeper Bob Wilson – the Arsenal Anglo-Scot and my later broadcasting colleague – which produced that eerie silence of anti-climax that sadly we recently had become accustomed to, in what had previously been a buoyant crowd. It is what happened next that confirmed we were in the presence of a new dynamic. Scotland equalised in exactly 60 seconds. Not only is an instant reply, to put you back into the lead, one of the most inspiring rebuffs to the opposition, but the manner in which it was achieved was as if the Doc had come out of the dugout himself to score it. For a man even smaller than the Doc, Archie Gemmill rose to a cross with their towering goalkeeper Damas and incredibly beat him to the ball and forced it over the line for a 2–1 victory. It ignited a volcanic response from the crowd. It was as if Scotland had played out one of his quick, fiery quips to flatten some loudmouth trying to outsmart him. The Doc had arrived. And with it came the kudos.

Jim Parkinson of the Glasgow Herald reported that Scotland ‘reclaimed some of the pride that has drained away from the Scots in international matches in recent seasons’. And the manager received the ultimate accolade from the great Eusébio who had retired injured in the game: ‘It was much better for the Scots than in Lisbon. Tommy Docherty has already helped Scotland. He is a very good manager.’ Davy Hay, with Celtic at the time and who played in defence that night, talked to me about the huge impact of that game on the players.

‘What counted was the way he could talk to you and drive you on. You just felt a bit taller and stronger after his words. He was tactically aware of course but I think it was his ability to coax you into a performance, that was his biggest asset. And, of course, I have a kind of affection for him because when Celtic were playing Ujpest Dozsa once and he was a pundit on a television show he called me “The Silent Assassin”. That name stuck to me. I think it was meant as a compliment. You know, I can put this simply. I enjoyed playing under him. And that’s the biggest compliment you can give a manager.’

The press conference afterwards was like a beatification after the recurring wakes of the tail end of Bobby Brown’s tenure. The Doc milked it for all its worth, as he was entitled to do, accompanied by a barn-storming session of quips to pressmen and broadcasters that we all lapped up like travellers at a desert well. The SFA did not drink at the well with us but preferred to give him his second contracted game before making any decision about his future. Scotland did triumph again against Belgium 1–0 on 10 November, after which he accepted the job, six days later, on what was called a ‘permanent basis’. The fact that the SFA had now appointed no fewer than ten managers in the space of 17 years, and linked it now with a man whose volatile nature caused him to bounce around the footballing world like a Mexican jumping bean, meant they were blissfully unconcerned that permanency was not a concept well understood by them, or by the Doc.

Then came Copenhagen on 18 October 1972. It helped shape his long-term future and sucked into his orbit the Celtic manager Jock Stein in a duel that even affected Stein’s health. The Doc had stabilised the squad and had lost only one competitive game in that time, against England 1–0 at Wembley in the British Championship. The Idrætsparken stadium that night was surprising to those of us who had never been in that country before. We expected the crowd to reflect something of their nation’s reputation for cool, austere design given that their furniture was all the rage in the UK at that time. In fact, they were as belligerent a crowd as any I had witnessed around Europe, but made little impact on the Scots whose 4–1 victory turned out to be one of the most significant on foreign soil, with consequences that went much deeper than historical statistics and the easing of our path towards qualifying for the 1974 World Cup in Germany. For back in Scotland Stein was watching this with interest because one of his players had starred in the game. Stein, alert as always, had sniffed something was afoot.

THE TUG O’ WAR

A troublesome triangle had formed. It comprised of the Doc himself; Lou Macari, a favourite player of his; and the manager of Celtic, still in command of his patch. Central to all the twisted events of the aftermath was the man who scored the opening goal in Scotland’s astounding 4–1 romp, which had an even more intoxicating effect on us than some of the local Carlsberg brew we partook in celebration. Lou Macari put a gleam in the Doc’s eye. Small, elusive, fleet of foot and nipper of many goals, he bonded immediately with the manager who saw in him something of himself, short in stature, but with abundant confidence and ability. But I could tell from my chats with him in his early days with Celtic that Macari was no ordinary man. It did not surprise me that when I met him in England during his managerial career down there he had set tongues wagging with his unconventional management style which bordered on the bizarre, especially when he appointed a former professional circus clown as his kit man at Stoke City. But what lifted him above the mundane was his social conscience. This became dramatically evident when during the Covid epidemic in 2020 he set up shelters for the homeless and provided them with the basic sustenance to survive. This led to his development of ‘glamping’, the system of pods which put roofs over the heads of many who would have gone without. All that indicates that Macari was a man of independent mind who, after that Denmark game, would become the centre of one of the great footballing tug o’ wars between the two giants Matt Busby and Jock Stein. It was firstly about Stein that Macari wanted to talk when I spoke to him from his home in Stoke.

‘I played under Jock Stein who never spoke about the opposition, never talked about any of their players, and if he did he just rubbished them to give you the sense that you were better than them. Tommy was the same. He never laid out any schemes based on their players. He talked about ourselves. And he was just great company. He would make you relaxed in the dressing room. It was a laugh a minute. He was the funniest man I ever met in life, not just in football. And before you knew where you were, you were heading out to play, with his last words something like “Go on. I know what you can do. Go out and do it.” Simple.’

The night in Copenhagen had turned out to be such a contrast to some previous trips abroad when you had to skulk back home. We knew we were returning to ecstatic headlines like that of Glasgow’s Evening Times the following day, ‘Our Best Team In A Long Time’ with the experienced writer Hugh Taylor almost beside himself with admiration,

So one swallow doesn’t make a summer and we are a long way from the finals in Munich, but this is the best combined Scottish team I have seen – a young team geared for attack – and how they attacked.

And significantly the Doc went public with some words of gratitude to the men whom he knew might influence his future one way or the other. He told the Evening Times the following morning, ‘Incidentally I greatly appreciate the telegram of congratulations from Scotland’s football writers. These things mean a lot.’

It was obviously the start of a love affair. Sadly, it only lasted a few embraces. For another man was in the throes of admiration. That was the very evening that Sir Matt Busby, having seen the action from Copenhagen on television, was finally convinced that he had to bring the Doc to Old Trafford. He had watched an attacking performance that seemed to fit the nature of United’s proclaimed vision of football – on the front foot, progressive, adventurous. At that stage Sir Matt was simply a director of the club, but nobody disputed the fact that he still carried enormous influence there and as he had revealed with his previous interest in Jock Stein, his Scottish genes were vibrating again. Lou Macari acknowledges that.

‘Sir Matt and the others sat up and took notice of the manager. Here was a fellow Scot who had gone to Denmark and won, but won handsomely in attacking style, and, of course, that’s got to be the way at Manchester United as many managers have found out to their cost.’

Scotland did indeed win their second game with Denmark at Hampden 2–0, with the opening goal scored in only two minutes by a young player called Dalglish; a result that enhanced the notion that Scotland would reach the World Cup finals for the first time in 16 years. Meanwhile, United sacked their manager Frank O’Farrell on 19 December 1972, at the same time as George Best was writing a letter to the United board stating categorically, as reported in the Glasgow Herald, ‘I have decided not to play football again. And this time no one will change my mind.’ He hadn’t met the Doc yet! But United were in a mess. After a 5–0 defeat by Crystal Palace they were in danger of relegation.

I have little doubt that the Doc knew, either by press gossip; or instinct; or actual contact, which in that business was hardly unheard of; and that given United’s interest, he was already beyond Hadrian’s Wall on the way south. Over and above that he had experienced, as a player in two World Cup finals, the instability of the national managerial post. In 1954 in Switzerland the SFA had their manager Andy Beattie walk out on them, because of interference in his player selection, after a first game defeat by Austria, 1–0. Manager-less in the following match, they were run over by Uruguay, 7–0. In the World Cup of 1958 in Sweden, with Matt Busby unable to take on the job as he was recuperating from his serious injuries of the Munich air disaster, it was left to the trainer of Clyde, Dawson Walker, to take overall control of the squad, but the team talks were led by the goalkeeper, Tommy Younger. Doc, in later years used an old Glasgow expression to describe the SFA’S handling of these events: ‘They couldn’t run a menage!’ Being witness to a succession of events that made the SFA seem like a three-wheeled waggon competing for customers in the age of aviation, made him very wary of how this would turn out for him. But it was an offer that had put him back into the limelight from relative obscurity. He had to take his chance. But United were now offering him a renewal in England.

‘There is no way he could have turned down the United job,’ Lou Macari told me. ‘For a start he would be getting a huge increase in his wages. And there was a challenge for him because as he could see himself he still had great players there, or at least that’s what he judged before he went.’

His acceptance of the United post produced an appropriate headline to Ian Archer’s article in the Glasgow Herald the day after the news broke of his resignation. ‘No Need For Wailing – Docherty Has Left A Rich Inheritance’, under which he wrote, emphasising the views many of us had about his tenure, ‘Those of us who followed him around the grounds and in trains and planes, always suspected that his term as Scotland’s manager might be short.’

It had been 14 months. So United gave the Doc double his Scotland wages of £7,500 and from the outset he saw the need for change. The player he wanted most from Scotland was Lou Macari and Jock Stein the Celtic manager knew that now, only too painfully. He would know that the Doc would be hunting Macari. And he would know Matt Busby would be looming large over proceedings. Over and above that he would know Macari would jump at it because he was in a long-standing feud with Celtic about wages. Stein was a bad loser. There was no way he would bow the knee to the man who had taken the very United job that he had turned down after his Lisbon triumph. Pride was involved. Stein made it his mission to prevent it. But, despite the Celtic manager lending the impression that he was invulnerable, the pressure of dealing with games and the increasing demands of more emboldened players to speak up about money was seeping through his defences. Stein had an explosive temperament and his anger over Macari might have tipped his health over the edge. One day, in the final week of December 1972, driving out of Parkhead with the Macari issue still burning in his mind, he became ill and ended up in the Victoria Infirmary because of an underlying heart condition that was to lie in ambush for him a few years hence.

Certainly, he had tried everything he could to prevent Macari from moving to Old Trafford. He had gone out of his way to arrange a meeting between his player and his old mate Bill Shankly at Liverpool, with the obvious encouragement to sign for them. It is a meeting that was observed by a United visitor, assistant manager Pat Crerand, who alerted United to that. The Doc, now firmly installed at Old Trafford as manager, swooped. Stein’s particular anger mostly stemmed from how he thought he had been duped by Lou in allowing him to believe that he would sign for Shankly. But in accepting the inevitable, in a final flourish he insisted that United pay £20,000 more than he would have accepted from the Liverpool manager.

As Stein lay in his bed in the infirmary on 6 January 1973, listening to the radio commentary of the Old Firm game and hearing of his team losing 1–0 to Rangers, he knew Lou was on his way south. Two days later the Doc had got his man. The player is adamant that he handled the process fairly. They had offered him a deal which simply enriched him.

But he also told me, ‘I went because they were struggling so I knew I would get my chance there to play at the top. And I also went because Best, Law and Charlton were there. Little did I realise that the Doc was going to get rid of them. Indeed, they were the only three players I saw him falling out with and getting really angry over. And, of course, I just got on well with the Doc.’

Most people did. Little did I realise that the game at Hampden against Denmark on 15 November 1972 would be the last time I would watch him manage any side. He was lost to me for years as he continued to ply his trade, principally with Manchester United, and so many others, which gave rise to his famous utterance, ‘I have had more clubs than Jack Nicklaus.’ Or, still being able to smile adversity in the face like his reflection on his time at Rotherham, ‘I promised I would take Rotherham out of the Second Division – and I took them into the Third. The old chairman said: “Doc, you’re a man of your word!”’

It was when he left United in 1977 that we met up again. One night in a Stirling hotel, late on at the bar, just after both of us had spoken at a dinner to a packed audience, he revealed a bitterness that I had never witnessed before. It was shortly after he had been abused by fans in a railway station who had shouted lewd remarks to him about the exposure of his love affair with the wife of the Manchester United physiotherapist Laurie Brown. He brought it up himself, as if he wanted to unload his frustration on someone. Not a plea for sympathy, just a burst of anger, and then it passed. Perhaps it wasn’t the lewdness itself that still irked him, but a stark reminder of what the terracings can do with mention of sex and of how the relationship ended his career at United. When he talked to me that night, he did not mention Sir Matt by name, but his bitterness about the club sounded like a proxy attack on the saintly figure of the great Scot whom he felt could have supported him. He actually said when he left that he was the only manager ever to be sacked for falling in love. I suppose it was difficult for many of us to associate this witty, but also pugnacious personality, with romantic inclinations and perhaps it was too obvious for his detractors to associate his relationship with the wife of physiotherapist Laurie Brown as anything other than venal. Clearly it was not. Equally clearly he had committed adultery and that collided terminally with the morality which stemmed from the figure of Sir Matt. There was no chance of survival there under the circumstances.

But, of that night when he opened up to me, he had reinvented himself as an after-dinner speaker and being on the circuit myself at times, I was meeting him frequently. Frankly, he made my efforts sound like readings from a telephone directory. It seemed easy for him. You could imagine him using that sharp wit in a street in Shettleston or in a dressing room coping with massive egos and proving nobody could top him. He could convulse a room of fat cats in the burgeoning hospitality environment of the modern game, or have them rolling in the aisles at a miners’ welfare. Much of it was self-deprecatory, but even though he used the same material repeatedly, it was always like listening to him for the first time. He had never really left Shettleston behind. It echoed in every quip, and the instinct for survival honed in those streets kept him buoyant when many others would have sunk without trace. It kept him going to the age of 92.

However, that night in Stirling when, for a fleeting moment he did look like a tired and beaten man, was in stark contrast to the day at the BBC in 1971 when I had first encountered a bubbling personality in his prime. That was the Doc I care to remember – brimming with self-confidence, unperturbed by the cloistered nature of the BBC, determined in a way that reminded people of the Hollywood tough man Jimmy Cagney. Add the impish Puck of A Midusmmer Night’s Dream to that description and you get close to what he was at his peak. And, indeed, we settled with him that day. He accepted £200 pounds. A sum which, at that time, took our breaths away. In 2021 it would have been the equivalent of £1,200. It was daylight robbery. The kind that came naturally to a Bowery Boy.

At my fantasy table I would sit boxer Jackie Paterson next to the Doc. They were both wee men who could punch above their weight. Paterson literally so.

CHAPTER 2

The Punch

ON THE 23 December 1985, Umkhonto we Siswe an operative of the banned African National Congress planted a bomb in a rubbish bin outside a shopping centre in one of the paradisial stretches of the South African coast, where golden sands and white-crested surf provided the perfect seductive poster advert, even for a country poisoned by apartheid at that time. There was nothing particularly exceptional about the statistics of five people killed and 40 seriously injured as a result, because even worse events had been occurring in the struggle against the existing political system. In that sense, when I read about the atrocity, it might have been swallowed up among the other ghastly incidents which had taken place and simply laid aside. But something stirred me, subconsciously. It was the specific name of the town where the atrocity had been committed. Amanzimtoti. I knew I had seen it somewhere before but couldn’t quite pin down its strange echo in the mind. But then it did break through the fog, and it struck me with a force that drew its strength from the indissoluble links with boyhood. A hero of mine had died there years before. According to the report he had been murdered – a broken bottle thrust into his neck where once fists, garbed in boxing gloves, used to land. A later report described it as an accidental fall on broken glass during a drunken binge. But, whatever, it was the squalid end of Jackie Paterson.

That Zulu place-name brought back to me the sadness I felt in hearing of his death on 19 November 1966, just as Tommy Docherty was still pulling them in at Stamford Bridge. It was thousands of miles distant from the environment where Paterson developed into a world boxing champion. He had entered my early years like a legendary knight, slaying dragons and putting villains in their place with his unsheathed, famed right hook. He also gave me one of the nights of my life.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that you could get on in life in Glasgow if you were handy with your fists. If you used them spontaneously in the streets you could gain awesome neighbourhood credibility. If you worked hard at cultivating them within the constraints of the noble art and made the gym an essential part of your life, you could conquer the world. Jackie Paterson, in the boxing ring, did exactly that. His birthplace was actually in Ayrshire although his frequent presence in Glasgow rings lent the impression he had slugged his way up from the city’s streets. He achieved success particularly with his famed punch, which from early on in his career had secured him a place in the demolition business. So, when I was told I was to be taken to see him in action for the first time in 1946 and, more than that, defending his World title at our great national institution Hampden Park, especially against an Englishman, I felt I was being ennobled. In retrospect I also believe that my father, whom I cannot recall ever attending a church and chose a registry office for his nuptials, must have assessed that night as the equivalent of a coming-of age ritual, somewhat akin to a first communion or a bar mitzvah.

He simply adored the little flyweight and spoke rapturously about his right hook, like an arms salesman extolling the virtues of the Kalashnikov. It was almost like listening to the incantation of boxing liturgy when he would return from a fight and describe it to me, blow-by-blow, like he was still on a high from just having seen Paterson put someone on the canvas, which he sometimes did with apparent ease. My father, a baker, was little different from many other men in our neighbourhood who could talk with authority about that sport and mix it easily with their other passion: football. Manliness, apparently, was not simply about the hair on your chest, but your ability to segue from one sport to the other and talk with authority about both, in the sure knowledge that you were confirming the proper characteristics of your class. And your sex. At that time women in my neighbourhood were in purdah, rarely seen inside a football or boxing stadium, or heaven forbid, drinking in pubs. A blinkered patriarchy existed. And, yes, men who showed no interest in the testosterone-induced passion for the two sports were considered odd. About that time I was to become aware of the exclusionary word, ‘poof’. Contrast that with the liberated 1984 Olympian Sandra Whittaker, whom I present in a later chapter.

But it was a fighter who came before Paterson that spurred my interest in the southpaw. In 1982 I wrote and narrated a short film for BBCGrandstand on John Burrow’s excellent book Benny: The Life And Times Of A Boxing Legend. Paterson, who trod in the footsteps of Lynch had to come up in discussion. So that short film drove him into my vision again and revived thoughts of how ‘twinned’ football and boxing were in my city.

This was expressed well by Tommy Gilmour, a contemporary of mine, who maintained the highly successful family traditions of boxing promotion, stretching back to his grandfather who could claim to be an amateur champion of Great Britain himself, when he wrote in his autobiography, A Boxing Dynasty: The Tommy Gilmour Story