Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

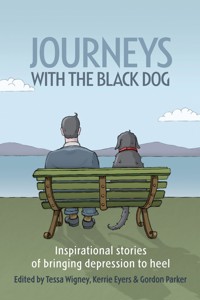

Depression can be a dark and lonely experience: sharing with a friend can make all the difference. In Journeys with the Black Dog many people share their stories of living with depression. Personal stories of first symptoms, the path to getting diagnosed, the confusion and frustration, and all the many ways of keeping depression at bay - whatever it takes. Written with raw honesty and sharp humour, these stories demonstrate it is possible to gain control over depression. Journeys with the Black Dog is genuinely inspiring reading for anyone who suffers from depression and those who care for them.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 353

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

TESSA WIGNEY is a writer with an Honours degree in Sociology. She is undertaking a PhD at the University of New South Wales, based at the Black Dog Institute.

KERRIE EYERS is a psychologist and teacher, and is the Publications Consultant at the Black Dog Institute. She is editor of Tracking the Black Dog (UNSW Press, 2006).

GORDON PARKER is Professor of Psychiatry at the University of New South Wales, and Executive Director of the Black Dog Institute. He is a mood disorders researcher with an international reputation, and authored Dealing With Depression (Allen & Unwin, 2004).

www.blackdoginstitute.org.au

JOURNEYS

WITH THE BLACK DOG

Inspirational storiesof bringing depression to heel

Edited by Tessa Wigney, Kerrie Eyers & Gordon Parker

First published in 2007

Copyright © Black Dog Institute 2007

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Journeys with the black dog : inspirational stories of

bringing depression to heel.

Bibliography.

Paperback ISBN 978 1 74175 264 9

E-book ISBN 978 1 92557 583 5

1. Depressed persons - Biography. 2. Depression, Mental.

I. Wigney, Tessa. II. Eyers, Kerrie. III. Parker, Gordon, 1942- .

616.8527

Internal design by Lisa White

Pawprint artwork by Matthew Johnstone

Set in Bembo 11.5/15 pt by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Printed in Australia by McPherson’s Printing Group

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Foreword

Acknowledgements

An invitation

1.

The landscape of depression

Introduction to the illness

2.

Into the void

Confusion and chaos at onset

3.

The slippery slope

Sinking into depression

4.

At the edge

Lure of the dark sirens

5.

Stepping stones

Diagnosis and disclosure

6.

Finding a way

The power of acceptance and responsibility

7.

Roads to recovery

On seeking professional help

8.

Travelling companions

Perspective of family and friends

9.

Staying on course

Wellbeing strategies

10.

The view from the top

Some positives

Tips from the writers on maintaining wellbeing

Afterword

Where to from here?

Glossary

References

Foreword

The suffering of depression is difficult to quantify, which is why story and metaphor are so valuable. While there have been many inspiring and evocative descriptions of depression (Kay Jamison’s An Unquiet Mind (1995) and William Styron’s Darkness Visible (1990) are key examples), most such accounts have been written by people highly prominent in their own professional lives, raising the question: Can everyone expect such positive outcomes? This book reassures us that, yes, it is possible.

The narratives in this collection arose from a writing competition organised by the Black Dog Institute, which called on people with mood disorders and their family members and friends to describe how they live with the black dog. The wealth of stories so benevolently shared contains precious insight and practical wisdom which help deepen our understanding of what is often a ‘silent disease’. Individuals chart their journey with depression—describing its forerunners, its onset and impact on their lives, and, for many, their achievement of self-management, and in some cases even transcendence.

This collection captures the voices of hundreds of people aged from fourteen to over seventy, ‘ordinary’ at one level but at another level extraordinary in demonstrating their resilience. Many articulate that developing a mood disorder made them a ‘better person’. Collectively, the grit with which these writers navigate the rocky terrain of mental illness, and the generosity with which they share their wisdom, humour and practical strategies, is motivational.

One of the great privileges of working in the mental health field is that while you see people at their worst—in terms of psychological distress—you also see people at their best. During times of mental turmoil, individuals are often open, undefended, vulnerable, yet paradoxically displaying remarkable resilience. Not only do they have to deal with a harrowing mood state, but also with the associated impairment which infiltrates their relationships with partners, friends and colleagues, as well as their capacity to work. Regrettably, this struggle commonly occurs with little external recognition or acknowledgement of the severe physical and mental anguish they are fighting, or the deep reservoirs of personal strength needed to sometimes simply face the next second, the next minute or the next day.

This collection presents a selected set of writers, in relation to the type of ‘depression’ they experience. Depression can range from the very physical types such as bipolar disorder and melancholia, through to the non-melancholic disorders that typically reflect the interaction between life stress and personality style. We were struck by the extent to which the writers described a particular type of depression—melancholia. Melancholia may be precipitated or augmented by stressful events but, as with other illnesses such as Parkinson’s syndrome, there are also changes in the neurocircuits of the brain that have profound effects on the sufferer. During a melancholic episode, not only does the individual enter a world of intense blackness and experience a desperate sense of futility and hopelessness, but also it is a very physical state. As an individual once described, ‘It is as if my brain is in a bottle beside my bed’. During such times a normally active and vital person might find it difficult to even get out of bed to wash or eat. In such near-paralysis, an individual might need someone to feed and wash them, even to take the lid off their medication bottle.

It is not always easy to know how to connect and be empathic with an individual experiencing the black dog of depression. As a consequence of the mood state, the depressed individual becomes asocial and insular, retreating from relationships and closing down communication channels, including those with their intimate partner, their family members and their friends. Dilemmas faced by those who care are obvious—to retreat or advance, to feel anger or concern, to offer advice or stay quiet, to protect or respect? The voices in this book provide some answers about how support can be offered—sometimes through practical strategies, but most simply through increasing understanding of the profoundly disabling and affective nature of the beast. It is clear from these stories that support and a sense of connection are important factors in generating resilience.

A common analogy used in the stories is that depression is like fighting a war. In the battle for sanity, there is a desperate scramble to survive the threat to self, to discover a path, and then to stay on it in an attempt to navigate through and escape from one’s mood disorder. It is an unknown landscape, often with no clear end in sight. Thus we note a consistent theme—This too will pass. For many, these four words have become a mantra, an integral part of the coping repertoire for both sufferer and carer. This realisation, in concert with appropriate medication, professional help and social support, can help counter the sense of profound isolation, hopelessness and negativity that is depression, reminding the individual that the state is not permanent and that they can once again regain their balanced sense of self.

Participants felt they had personally gained through writing their story. For some, this was the first public admission of having suffered depression and they were surprised to find that setting down the shape of their ordeal was therapeutic. This collection reveals there is no one correct ‘way’, yet taking up responsibility for one’s own pathway through depression was almost universally quoted as the first stage in learning to live with the illness, including, for many, a recognition that the black dog was likely to be a companion for life. We hope you will be inspired by the fighting spirit that grounds so many of these voices.

Tessa WigneyKerrie EyersGordon Parker

Note: For anonymity, identifying details have been changed and all writers were assigned a number. This number appears at the end of each story. All royalties from this book will go to the Black Dog Institute to support its Consumer and Community program.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our warm gratitude to the people who helped make the writing competition, and hence this book, a reality. Hats off to our three judges, Anne Deveson, Margret Meagher and Leanne Pethick, for surmounting the huge task of selecting one winner amongst them all; our indebtedness to Sue Grdovic, our Community Project Manager, for her tireless efforts behind the scenes; and Ian Dose, our PR Manager, for his boundless energy in shaping and promoting the competition. A fond tribute to Matthew Johnstone for his inspired artwork and special thanks to Peter Bakowski, Leigh Kibby and Michael Leunig for kindly granting us permission to include their own creative gems; and the R.A. Gale Foundation for their generous donation in memory of Duncan Snelling. Finally, our warm appreciation to all six hundred and thirty-four entrants whose spirit and grace illuminate these pages: without your voices there would be no story to tell.

An invitation

No-one enters the labyrinth of depression willingly. So if you find this book in your hands, you have probably been led to it through your own pain and your own search for answers.

Or you may be a caregiver, family member or friend who is charting the peaks and troughs of life with depression as you witness the struggle of someone you love.

It is our hope that you find wisdom and inspiration in these pages—perhaps even a little humour to bring a wry smile.

This book is a map, of sorts. All the voices contained within these pages are the voices of those who have journeyed with depression, and they evoke a landscape with many reference points. Individuals share their stories, their advice, and the strategies that help to keep them well.

As you read, you may be moved to reflection, so you might like to keep pen and paper handy to record your own responses, questions, ideas and thoughts on your own journey so far.

And so we begin . . .

The traveller who looks immediately behind,

Sees only the dust of the journey.

The traveller who looks immediately in front,

Sees only the next footfall.

And the traveller who looks all around,

Sees the trail as it winds from valley to hill,

Sees the sky at day and night,

Sees the creatures, plants and land,

And sees a reflection in the stream,

And sees as far as the eye can see,

And thinks as far as the mind can dream,

And feels as deep as the heart can be.

Leigh Kibby

Truth be known, my sofa deserves anOscar. An Oscar for the best supportingfurniture in a clinically depressedepisode.

1. The landscape of depression

Introduction to the illness

On a moonless night he comes, the epitome of malevolent darkness, stalking his prey with the endless patience of a predator, glowing yellow eyes gazing ever-watchfully at me, seeking a weakness, hypnotic eyes, second-guessing every move.

Following, ever following. Slip and he strikes, ready and willing to tear out my throat. Invincible he appears, powerful haunches, razor-like fangs framing a long muzzle. A blood-red tongue lolling in a spiteful sneer, a powerful body, black shaggy fur matted with blood, his battle trophies he wears with fierce pride.

I can never be fully rid of him, for he will always be there, lurking in the back of my mind, ready to strike . . . All I can do is lengthen the time between his attacks.

It is often very difficult to understand how depression feels if you have not experienced it yourself first-hand. Most people with a mental health problem will say that the experience is virtually indescribable, that the pain is incomprehensible, that there are simply no words to adequately explain it.

This attempt to explain the nothingness, the darkness, the pain and despair seems to fall drastically short of the indescribable horror of my self-despised existence. The isolation between sadness and total despair were the parameters in which I functioned. How could anyone understand? I couldn’t understand. I had become the black dog’s dog.

That is why metaphors are so often invoked, to provide an image that will help others move a little closer to understanding the suffering inherent in depression.

I walked the path of emptiness with despair my loyal companion, struggling through a sopping mud pit that sucked at every morsel of energy I possessed. It was a numbness that hung over me like a stinking skin of rotting flesh, putrid and decaying with the deception of each dawning day. I loathed every breath of my existence.

I felt besieged. It felt like my head was a hellish prison, a gloomy and frightening labyrinth alive with relentless, malevolent beasts; like someone had taken out my brain and put it back in sideways.

Of course, pain is a very subjective experience, no matter what the illness. But what is not often understood about depression is that the suffering goes well beyond the physical realm of insomnia, loss of appetite and low energy. Depression infiltrates your thoughts and takes over your mind. It distorts your senses, as well as your perception of the past and the future. It is a state of excruciating isolation. It fuels the most negative emotions: excessive guilt, disabling sadness and despair, and crippling self-hatred. At its worst it can hijack your most innate survival mechanism—the drive for self-preservation. To put it plainly, for most, depression is a living hell on earth.

Deeper and deeper I fell into the black pit of hell, tumbling down in a blacker than black bottomless pit, devoid of doors or windows. Hell on earth, a living nightmare.

However, as these stories illustrate, in most cases the sufferer’s sense of self, agency and future optimism can be restored with the right diagnosis, help, treatment, persistence, support and healing strategies.

Depression has long been an illness shrouded in a silence that has bred misunderstanding, fear and shame. Only by encouraging discussion and being willing to listen and share personal experiences can we hope to generate a discourse that will help demystify the condition. Through the richness of these stories, we gain insight into the world of suffering that is lived depression, an invaluable perspective that will help develop a more compassionate understanding.

Each day was like having to drag your own shadow around behind you—heavy, weighted, leaden.

The accounts collected here create a multi-dimensional view of the experience of depression. In piecing together these vignettes, we aim to capture the essence of what depression feels like in order to fully represent the depth of suffering involved in coming to terms with such a disabling, and often misunderstood, condition.

Indisputably, however, in seeking inspirational stories about how people cope with depression, a certain ‘type’ of depression account has been privileged. We are therefore conscious that this collection is biased towards those who describe a positive resolution to their depression story—a focus which, it could be argued, fundamentally opposes the very nature of depression itself. One writer read the tide, and swam against it:

I am not going to be cheerful or optimistic about depression. I am not going to fabricate a worthy tale of recovery which ends with an uplifting thought. I have no story of how I am grateful that depression has given me insight. This is not an inspirational story. This is a story about why inspirational stories do not help; how they do not speak to me; how they alienate me, exclude me, tell me I do not belong in a discussion about something that is intrinsic to who I am.

There appears to be a dissonance between the possibility of redemption and recovery, and what people actually say about their experiences and their despair. What does it feel like for someone who is depressed to encounter these stories? In seeking inspirational stories, what kind of talk about depression is being asked for? It suggests the language of parables, of mythology, of the hero overcoming obstacles—a desire to see the overcoming of adversity by people like ourselves.

There is a need for discourse but there’s also a need for stories which are not uplifting, which express hopelessness and what depression is actually like, stories that are not addressed to someone who is not depressed.

The competition framework could also be taken to exclude many other experiences of depression, for example, from those who may lack the resources, capacity or ability to articulate their experiences.

Yet it is not our intention to exclude, or silence, the darker aspects of dealing with depression. In many stories, a very bleak reality is presented. There are many harrowing elements that touch on negative aspects such as self-harm, suicide attempts, hospitalisations, relapse, and drug and alcohol abuse. Yet some of the most motivational narratives are precisely those which have highlighted the ‘ugly nature of the fight’ because, in their honest description of the journey from torment and attempts at self-destruction to some form of resolution, the reader gains insight into the true nature of the battle and the reservoirs of determination and strength needed.

So while we recognise the extremes of desperation within depression, we have chosen to emphasise the positive aspects of the journey towards wellbeing. For alongside each distressing testimony there emerges a resolution—a gathering resilience, tentative hope and growing strength—and it is the effort of moving forward that is the ultimate focus of this book. Taken as a whole, the collection evidences the indomitable strength of the human spirit.

The stories we have chosen are inspiring—even if only in reassuring others that they are not alone. While we do not want to impose a concept of recovery onto the accounts, in synthesising these stories we do hope to highlight the fact that coming to terms with depression is an unfolding process and there are many avenues open to individuals trying to negotiate their way through their illness to a more mellow (albeit vigilant) adaptation.

Any victim of depression can find stories of people who fell by the wayside. It is not often that stories are told of inspirational people who recover and reclaim their lives. I have never shared my story before. It has been a closely guarded part of my life. We live in a society that still doesn’t look kindly upon those who have suffered in this way.

Dealing with depression raises questions, many of which remain unresolved. Sufferers do not simply have to learn how to cope with physical and psychological symptoms of the illness, but also with related issues of freedom, determinism, responsibility, destiny and choice.

Why? I don’t deserve this! Why not? There’s no answer to either question. It just is. It’s up to you whether you allow it to take over your life.

How did it start? When will it end? Was I born this way? Or destined? I will never be the same. I have changed immeasurably.

The narratives that follow show that there is no one way of coping with depression. Everyone reacts to and deals with it differently—just as people have unique personalities, goals and dreams, so too do they have distinct ways of managing illness.

Depression is part of me, just like my smile, my laugh and my tears. It is all me and, like everything else about me, it is individual.

There’s no easy answer. What works for one person may not work for another.

Beyond doubt, each individual has to find their own path through the pain and struggle to find their own meaning. As depression strikes at the heart of what it means to be human, understanding its meaning—whether medical, biological, social, existential, practical or spiritual—is pivotal in learning how to cope.

Depression has much more to do with the soul than with science.

Meaningless itself has meaning. It forces us to find, or to make, our own meanings. Lack of meaning provides the landscape in which we can seek out new truths and rediscover that which gives us purpose.

The level of engulfment—the extent to which depression is perceived as peripheral or dominant in people’s lives and identity—is varied. Individuals often find themselves fighting to balance the split between their actual and ideal self. Some individuals cope by identifying with their illness and learning to co-exist with it. They come to accept it as an inherent part of themselves:

I live with it because I am alive, and it lives because I am alive. It’s a strange and often amicable symbiosis. It is me. To curse this depression is to curse myself. I hope one day to be well. But for now, this is who I am.

Nobody asks for depression. Nobody enjoys it. Nobody wants to live with it. NOBODY uses it as an excuse to garner sympathy or hurt others. When I refer to the ‘black dog’, I am referring to the person I become when I am unwell. I AM the ‘black dog’. I BECOME the ‘black dog’. It is not a separate entity.

It’s a part of who I am, and although it sounds strange, I wouldn’t feel me without it. I have to ride it out.

Others manage by separating the condition from themselves and regarding it as something external to themselves:

Depression doesn’t define who you are. You are a person coping with an illness.

I find it liberating to visualise this illness as a black dog that is separate from the bright, friendly, capable woman I know myself to be. I live with it by acknowledging his presence, not feeling guilty for his existence.

Typically, a diagnosis of depression catapults individuals into a complex trajectory of distress and adaptation. For some, diagnosis is welcomed with relief, representing a positive turning point and vital step in seeking treatment:

It was a huge relief to know that my problem was depression—not failure, weakness of character or a flawed personality.

For others, diagnosis is the trigger that turns their world upside down and threatens their entire self-concept and sense of coherence:

The diagnosis shocked me. I did not believe it. I’m not the sort of person who gets a mental illness. I am in control of myself. Surely the doctor has made a mistake. I don’t have time to be ill.

A common thread that runs through these stories is one of loss and grief—loss of authentic self, agency, control, hope for the future and capacity for pleasure:

The girl in the photo, it’s me. I remember her but she seems like someone I loved, but lost, and now grieve for. I want to write in the second or the third person, to isolate me from the ‘dog’, to give the ‘dog’ its own entity, to show depression and me as two separates living parallel, occupying the same space. I can’t. I am the black dog, and he is me. We are a single, inseparable unity, greedily possessing and devouring each other . . . I stopped being me a long time ago and I grieve for the things the black dog has stolen from me and buried like a bone in the dirt.

I faded away to a shadow of my former self. It’s a savage disease that destroys your very soul and the essence of your being. Depression takes away the one thing that you thought could never be taken—yourself.

Yet, while the overwhelming, debilitating nature of depression is explicitly portrayed in a selection of these stories, there is also a strong message of empowerment. For the majority of our writers, it is clear that being threatened with depression does not mean they have to be passive victims of their illness. Choice—in deciding to seek help, pursuing treatment, asking for support—is still an option.

Depression is a real illness. People don’t choose depression, but they can choose how to deal with it. It does not have to dictate your life. You are not your illness.

If things aren’t going well, don’t wait around for another person to help you. Get in and help yourself. The sooner you tackle a problem, the better. The longer you leave it, the more scars you will have deep down, and these scars take a long time to heal.

Consistently flagged through the accounts in this book is the need for early recognition of the illness, commitment to seeking help, taking responsibility for staying well and, at all costs, maintaining belief in a positive future. Those who attest to overcoming their illness often carry an enduring sense of vulnerability and emotional sensitivity. Many are fearful of future episodes and for this reason remain vigilant.

I am a survivor from a lifelong wrestling match with an entity that has tried to take life from me and I have emerged victorious, but cautious. I will always need to be vigilant. Judging from my family history, it is part of my make-up. I have lost too much of my life in the lacunae of episodes and the distress between them. I don’t intend to lose any more.

But, encouragingly, these stories illuminate a fact: the pain of depression can also heighten the capacity to experience joy:

There is an upside to depression—joy at being alive. I now have a wonderful appreciation for the good things in life. At times I feel pure exhilaration at being alive and a pulsating sensation from the very forces of life.

In the following chapters, we will explore the various paths used to forge a way through depression—initial confusion, disintegration, denial and escapism; reactions to diagnosis and disclosure; the role of acceptance and responsibility; and the support of others. The writers outline their coping repertoires, and describe what sustains and inspires them on the journey. We hope to provide a multifaceted foundation from which to view, and understand, the complexity of the ‘parallel universe’ that is depression.

Ultimately, the enduring message in these stories is one of resilience and hope.

This too will pass. This is the law of your life, the only law that you must remember.

To begin, six individuals tell their stories, charting their different ways of learning to identify, travel with, and finally master the black dog of depression.

With doubt on my side!

It’s a very tricky beast, that black dog. It can render your life intolerable and then tempt you with a fatal remedy, all the while robbing you of the energy to save yourself. And it achieves all this destructive mayhem in the privacy of your own mind. It turns your thoughts and emotions against you. Taming it may not be a quick process, but it is possible.

The most profound step in my recovery has been learning to doubt the veracity of my own thoughts and feelings. It was not an easy thing to come to terms with—that my inner landscape was not to be trusted. But once I could objectify my thoughts and feelings, I could allow the possibility of feeling better, that change could occur, and it was something I could build upon. The new serotonin-uptake medication was the final breakthrough I needed, but the confidence I have about staying well has more to do with insights into the nature of the illness.

Depression tricks you, it tells you lies, it is a lens that distorts your experience and it’s no-holds-barred when it comes to fighting it.

It’s been nearly seven years since it last blighted my life and I have revelled in every good, bad or indifferent day. Life without depression is like breathing without a flat, heavy stone on your chest and I’ll do what I can to stay free of it. I believe that learning to challenge my own irrational thinking, recognising that parts of my body other than my brain can affect how I feel, and the judicious use of modern pharmacology now gives me a considerable edge.

The black dog first bit down seriously in my early twenties when I was living in hippy paradise with my husband. As despair doused me, I became inert, balled up in bed for long hours, then weeping, balled up in front of daytime TV. I went back to bed early or late, whichever best avoided sex. My feelings had heightened significance and they were all awful. I felt a sort of superior insight, I could see how pointless and futile life was—why didn’t anybody else get it?

I made the sexual dysfunction a cause to seek help. I got genuine concern and sedatives at best, dismissive indifference at worst. It was the start of a pattern of reaching for help, which was a mixed bag of disappointment and relentless pessimism and tiny sparks of hope.

Over the next two decades the black dog turned up many times. While sometimes acute, my depression often tapered off to a low-level, grey numbness until I thought I was that person. Woven through all that was a sort of black romance with suicidal ideation. I planned and imagined, researched and obsessed. Only twice did I take any step towards action, and I pulled up well short of danger both times. But wanting to be dead was a regular part of my inner landscape.

Whenever I became overwhelmed with melancholy, with deep immobilising despair, my thoughts got busy making sense of it all. There was always plenty of grist for the cognitive mill as my life usually provided enough material to work with—relationship breakdowns, past hurts, an indefinable sense that there should be more. And if that wasn’t enough, there was always the state of the world—plenty to despair about there. I believed I deserved to feel this way, I had this special insight into how awful it all was, there wasn’t any other way to feel.

There were plenty of ideologies to reinforce my dodgy thinking. Depression is your frozen rage, or the result of a bruised self-esteem at the hands of your toxic parents, or even a past life. Just express that righteous anger, speak that truth, confront that fear, and you will be free. But those cathartic processes didn’t actually work because my brain was still stuck on a broken track—shunting me back and forth on a well-worn path of gloom and self-destruction. Like the emperor’s new clothes, no-one (least of all me) dared to say—maybe those feelings and thoughts are not real.

But my work with victims of domestic violence exposed me to some cognitive behavioural methods. Simple tools like affirmations (the lies you tell yourself until they are true) could peg back my destructive self-talk and slowly build a new outlook. I didn’t have to wait until I felt better to try to start thinking differently—the process could work the other way around. Some small relief could be gained with distraction, the mornings felt different to the nights. Giving my right brain some air time was also beneficial, drawing stopped the bullying verbal onslaught of my left brain. So did exercise, especially weight-resistance exercise. Of course, when my blackness was at its worst, I couldn’t find the energy to take any of those steps but I would get back on the horse as it abated and it gave me a small sense of control.

Finally, I got to the point where I could recognise that, despite having a good job, a caring partner and a life that was actually quite OK, the sense of doom could still be there. It wasn’t a true fit, it wasn’t about me at all, it wasn’t even about my life. It was just something my brain was manufacturing, in the same way that a big night on the red wine or some party drugs could leave me shattered and morose the next day. It would pass, and, with appropriate new medication, I could even shut down the suicidal thinking loop.

These days I celebrate all my moods, even the bad ones. I can be normally sad and I can have just plain old contented days along with everyone else. I can be happy too, but contrary to some ill-informed opinion, freedom from depression is not about seeking constant happiness. It is the absence of that black fog that numbs the senses, muffles sound, dulls colour, divides you from your fellows and invites you to see the sense in ending it all.

It’s been many years since I’ve needed medication. I have become a bit of a gym junkie and I no longer work in the despair industries, choices that I believe contribute to staying free of depression. But most importantly I know that ‘dog’ for what it is now. If its subtle workings started to bite into my inner landscape, I would ramp up all my efforts to expel it, including seeking medical help. I don’t deserve that pain, no-one deserves that pain, and I won’t give in to it without a fight. And I’ll win because I know that its toxic whisperings are delusion.

I have doubt on my side!

The D Club

I’m the perfect party guest. Put me anywhere and I’ll energise. Sit me next to the nerd and we’ll be digitising computers and code, saddle me up to an artist and it’ll be all art house and film noir, introduce me to a mum and we’ll be gushing over the new-born. Well, until baby needs a nappy change.

Yep, I’m an energetic kind of guy. I’m into things. All things. Passion is my mantra. Be passionate, be proud. ’Tis cool. ’Tis sexy.

What’s more, people respond. I ask questions. They give me answers. It’s like I have a truth serum aura or something. My intuition is strong, it is real, it is Instinct. It is David Beckham.

Well now that you have my RSVP profile and we’re on intimate terms, I can tell you a little secret. A kind of friend-for-life, confidante, I-trust-you-a-whole-lot secret. I’m not always the bundle of kilowatts you see before you. I’m not always the interested, interesting persona who invigorates, and who epitomises the successful young professional—the man about town who’s hip, happening, sporty and fashionable.

Yep, while I sit here typing this on my new ultra-portable, carbon-coated, wireless notebook, because looks are important, I am reminded of my darkest hours. ‘My achey breaky heart’ hours. And I hated that song from Billy Ray Cyrus and his mullet.

Only a few months ago I finished Series 5 of ‘Desperate Individuals’. It’s my own spin-off from Desperate Housewives, except with a limited budget there were no major co-stars or Wisteria Lane—just a cast of two, with my sofa taking the supporting role.

Truth be known, my sofa deserves an Oscar. An Oscar for the best supporting furniture in a clinically depressed episode.

My sofa does what it always does when I’m alone in my depressive mindlessness. Cradles me, protects me and warms me. We’ve become quite acquainted over the years since my late teens. We hide from the phone together, cry together and starve together. Ain’t that a shit. I have a relationship with a couple of cushions. At least they cushion me from a world I can no longer face, expectations I can no longer live up to, productivity that has left me behind.

It makes for good television. Because my life as a depressive is today’s TV. It’s 100 per cent reality. It’s repetitive. It’s boring. It’s cheap. It’s a mockumentary to everyone but the participant.

My sofa doesn’t eat; you can tell that from the crumbs under the cushions, and with clinical depression, I’m not hungry either, so we’re a perfect match. Food? My tongue is numb and I can’t taste anything so why bother.

Looking back, it’s hard to see when each period of depression started. That’s because most depressive episodes end up being a blur; a juvenile alcoholic stupor forgetting the hours between midnight and 4 a.m., except in my mental state it’s a whopping six months that are hazy and foreign.

Seconds don’t exist in my world of depressive dryness. Seconds have become hours. Hours are now days. Months are lost in a timeless void of nothingness. No sleep, no interest, no energy. And it is here that life becomes its most challenging.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m all for the comfortable cinema vicarious experience with stadium seating and popcorn. I just wish depression was a two-hour affair on a cold Sunday afternoon instead of the rigor-mortic torture that makes it too painful to stay in bed, but even more painful to get up.

Depression is incoherence—the death of wellbeing, direction and life. Everything aches. Everything! Your head. Your eyes. Your heart. Your soul. Your skin aches. Can you smell it? Oh yeah, ache smells and I’ve reeked of it. My grandmother ached. She told me just before she died of cancer. From then on I saw the ache in her eyes. Sometimes in the middle of a depressive episode, I see it in mine. To look in the mirror and see your own total despair is . . . horrendous.

Now all of this is sounding downright pessimistic and I mustn’t dwell on the pain of the past. After all, I’m here to tell my story when many others are not. For I write this not to recapitulate history but to shed a little light on an illness that affects 20 per cent of adults at some time in their life.

For those of you who have been or are currently clinically depressed, welcome to the club—the members-only ‘D Club’. Here’s your card and welcome letter, and don’t forget that we have a loyalty program. You get points for seeking help, points for talking to friends and family, and points for looking after yourself.

Now news headlines would count the economic cost of depression, which is in the billions, but from a human perspective, it’s simply a hell of a lot of agony.

The good news is that public perceptions, which not long ago relegated mental illness to that of social taboo, are slowly being broken. Courage, dignity and honesty can be used to describe Western Australia’s former Premier, Dr Geoff Gallop, who detailed his depression at the start of 2006. Here’s a small excerpt:

It is my difficult duty to inform you today that I am currently being treated for depression. Living with depression is a very debilitating experience, which affects different people in different ways. It has certainly affected many aspects of my life. So much so, that I sought expert help last week. My doctors advised me that with treatment, time and rest, this illness is very curable. However, I cannot be certain how long I will need. So, in the interests of my health and my family I have decided to rethink my career. I now need that time to restore my health and wellbeing. Therefore I am announcing today my intention to resign as Premier of Western Australia.

Stories like Dr Gallop’s allow more of us to talk about how depression can affect our health, jobs, families, partners and friends. It’s not a sign of weakness to express our inability to function mentally. It is in fact a sign of courage, openness, sincerity and trust.

It is not unusual for those of us who are suffering from depression to feel guilty, as if we have somehow brought this illness on ourselves, that we are weak, it’s all in our head, or that we’re somehow protecting those around us by hiding our mental paralysis.

Truth be known, so many of us are lost in today’s frenetic lifestyle that we don’t see the signs of unhappiness and helplessness in our loved ones. Sometimes it takes a meltdown to even see it in ourselves. But it is only through acknowledging mental illness that we can get treatment and start to finally feel better. Who would’ve thought that asking for help would be so hard?

For someone suffering from clinical depression, just to talk can be exhausting. During my last episode, I had repeating visions of falling asleep on my grandmother’s lap because there I could forget the worries of my world. Memories of her gentle hand caressing the back of my neck are safe and warm. A simple gesture can mean so much.

Today, instead of my grandmother, I have dear friends who offer to cook, clean, wash and care for me. They fight my fierce independence and depression-induced silence with frequent visits and constant dialogue. Their lives haven’t stopped, they don’t feel burdened and they haven’t moved in. They are now simply aware that I have a mental illness, and we are closer because of it.

I, too, have taken responsibility to seek assistance from qualified medical practitioners. Don’t get me wrong—taking the first, second and third steps to get help from a doctor can be traumatic. It’s not easy admitting that you’re not coping with life. And finding a physician who you feel comfortable with, and antidepressants that work, can take time. But I am testimony that you’ve got to stick with it.

And so, as I sit here and start to daydream as I look out of the window, I am reminded of a recent time when I lost my ability to sing, to share in laughter, to swim, to eat, to talk, to enjoy, when waking up was just as difficult as going to bed. It’s a frightful place that sends shivers up my spine.

However it’s a fleeting memory, because Mr Passion, that energetic kind of guy, is back, and he doesn’t have time to dwell on the past. This D Club member is in remission and it’s time to party.

Blessed are the cracked

What images does the term ‘black dog’ conjure up for me? It makes me think of those dark pre-dawn hours when you feel so melancholy, so anguished, so alone, and that gnawing feeling of overwhelming sadness has a vice-like grip on you, like the proverbial ‘dog with a bone’ (apologies for the obvious dog reference), and it feels like it will never abate, regardless of what you do. (Anyone who has suffered depression would agree that things always seem worse at night.)

I have chosen to write about how I live with depression for two reasons. Firstly, I thought it would be a great way for me to reflect upon myself and the way that I deal with my mood disorder, and thus enable me to live better with it. Secondly, I wanted to share with people the way that I deal with depression in the hope that my coping strategies may be of benefit to others.