Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Mercier Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

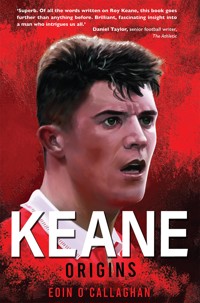

Pick your favourite Roy Keane moment. The header against Juventus? The tunnel clash with Patrick Vieira? The bone-crunching challenge on Marc Overmars at Lansdowne Road? All worthy choices that complement his aggressive, combative warrior persona. But that was Version 2.0. Keane: Origins delves into the inexplicable story of what came before. Focusing on the period between 1988 and 1993, charting Keane's journey from an economically-ravaged Cork to a spectacular three-season spell under Brian Clough at Nottingham Forest via a memorable stint on a government-funded training scheme and brief spell in the League of Ireland. With contributions from former team-mates, coaches and those who knew him best, Keane: Origins examines a largely over-looked, under-appreciated and unheralded time in the legendary midfielder's career that set him on the path to immortality.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 473

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To Joan, who I miss dearly.

For Lyndsey, who I don’t deserve.

MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

www.mercierpress.ie

www.twitter.com/MercierBooks

www.facebook.com/mercier.press

© Eoin O’Callaghan, 2020

Epub ISBN: 9781 78117 732 7

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Prologue

February 1990.

A Sunday morning.

A bitter one, with frost on the ground.

The sun glints through a windscreen heavy with condensation. Soft heads, sore eyes, warm bodies. The zips on their tracksuits pulled high, their temples resting on the windows.

Another trip to Dublin.

Belvedere again.

A replay.

Typical.

The first game was a nightmare. At St Colman’s Park, he’d put Cobh Ramblers in front with twenty minutes left and a massive win was theirs. Surely. Then a cross came in, the goalkeeper didn’t get there.

An equaliser.

A fucking mess.

The usual.

As the bus rattles along, Roy Keane stares into the abyss.

Frustration.

The relentless grind. And for what? The League of Ireland First Division? He’d spent the season with Ramblers’ first team and experienced enough shit-hole venues and bitter old veterans to last him a lifetime. He’d left Rockmount to test himself at a higher level. But this was a joyless, aimless, long-ball dirge. They’d tap him on the shoulder and say, ‘Fair play, Roy. Character building.’ Bullshit. He was a midfielder. Young. Creative. Quick. He spent most games dodging the craters in the ground and wild lunges from fellas twice his age. Occasionally, he’d meet a kindred spirit on the other team. They’d share a knowing glance. This was no place for them. But what else was there?

He’d gotten a taste of it underage. Pulling on a green shirt. People knowing his name. And then it went away. Turned out he was forgettable. Faceless. Confidence, that innate local swagger, was always second nature, but it was harder now. Friends were cross-channel, signed to proper clubs. They were on a path. And he was worried. Worried about what was next, if it didn’t work out. There was a pressure, a fear.

The FÁS course, the government football scheme he’d signed up for five months earlier, was coming to an end. He’d loved it. There was a purpose. He felt like a full-time athlete. He was improving. He was getting stronger. He was earning a few bob. But he was down the pecking order. Others were better than him. And there were still no trials, no phone calls, no interest. Would it have been different at Cork City? Maybe. But they’d annoyed him. They hadn’t even cared enough to get him registered properly. Another let-down.

But Cobh had backed him. They wanted him. They were there. They were loyal.

Their youth coach, Eddie O’Rourke, had watched him play as a kid. He’d waited years to get the chance to sign him. And Roy enjoyed playing for him. There was a freedom to the underage side. He could be himself. He could influence. He could dictate.

Today was Fairview Park, one of those heralded Dublin football spaces. With its litany of pitches and freshly manicured surfaces, it reeked of privilege. There was the multitude of whispering ‘insiders’ on the sidelines too, the Stepford Wives, all dreary anoraks and immersed in the incestuous workings of schoolboy football in Ireland. The decision-makers. The centralised stakeholders. Funnily enough, you’d never see them at a First Division game.

Fuck them too. This was for Eddie and those who believed in him. Those who knew his talent. Those who wanted him to succeed.

Part 1

‘If cities are sexed, as Jan Morris believes, then Cork is a male place. Personified further, I would cast him as low-sized, disputatious and stoutly built, a hard-to-knock-over type. He has a haughty demeanour that’s perhaps not entirely earned but he can also, in a kinder light, seem princely. He is certainly melancholic. He is given to surreal flights and to an antic humour and he is blessed with pleasingly musical speech patterns. He is careful with money. He is in most leanings a liberal. He is fairly cool, usually quite relaxed, and head over heels in love with himself.’

Kevin Barry

1The First Half

Dublin lets on to be a capital, Frank O’Connor once said. Keane had a difficult relationship with the place.

In 1982 The Late Late Show, RTE’s agenda-setting television production, focused on Cork for a particularly memorable episode. At one point there was a light-hearted vox-pop segment, where a reporter took to the streets of Dublin and asked the locals how they felt about Cork.

‘I think they’re a nice race of people,’ one man warmly offered.

There was never any malice intended. There was merely an assumption from Dubliners that anywhere outside of their cocooned existence was a kind of rural, agricultural wasteland with an array of madcap characters immersed in various kinds of buck-toothed buffoonery. Cork, the country’s second-biggest city and a place boasting huge historical influence, cultural resonance, a proud sense of identity and an acerbic wit, always took this worst. The ignorance, indifference and flippancy grated.

Keane was from Mayfield, at the heart of Cork city’s northside. He was in his early teens when his city was decimated, the heavyweights – Ford, Dunlop and Verolme – all shutting down their operations in the space of eighteen months from 1983 to 1984, deciding they didn’t need Cork any more. Thousands of fathers, including his own, were left to beg, borrow and barter for bits and bobs. When the country was gripped by recession in the late 1980s, it felt like Cork had already been battling it for a decade.

The city informed Keane, certainly. That runt of the litter mentality. They may not have had much, but what they had was special.

As it turned out, Dublin didn’t particularly like Keane very much either.

In 1987 he’d lost to Belvedere, an intimidatingly well-run and highly acclaimed club from the northside of Dublin, in an Under–15 national final in miserable circumstances. After forcing a draw in the capital, his Rockmount team surrendered a two-goal lead and lost 3–2 in the replay back home, missing out on a first Evans Cup success in twenty-five years.

He was there too for Ireland Under–15 trials but was ultimately ignored, deemed too small by the selectors. His Rockmount teammates Paul McCarthy, Damian Martin, Len Downey and Alan O’Sullivan all made the grade, which irritated him further. It had always been a solid quintet, a group made famous by the Kennedy Cup photograph taken when all five represented Cork at the Under–14 national tournament in 1986. Keane had captained that side to their first title in a decade as they annihilated an Offaly selection 10–1 on aggregate. Replete in their red and white, Downey is a towering presence on the far left of the picture. Second from right is McCarthy, already a powerful unit. Martin and O’Sullivan are a strong, commanding pair. All four have their shoulders back, chests out and hands clasped firmly behind their backs. A miniature Keane is dead centre, hands draped in front like he’s defending a free kick. His posture makes him seem even smaller, a world away from adolescence. Just a boy. But they were all in it together. Written off, abused, criticised. Only Rockmount. Still, the five of them got there. And the Ireland team was next.

But not for Keane. Yet.

He was already known as an elite schoolboy player, which made the snub all the stranger. At the country’s most influential football nurseries, the top brass were well aware of Roy Keane. And many of his fellow players and rivals were becoming aware of him too.

‘It would’ve been Under–12 or Under–13 level and I was with Home Farm,’ Tommy Dunne says. ‘We played that Rockmount team so I was up against Roy throughout the game. At that stage, he was sharp in his mind. A little bit ahead of his years in a way. His movement was really good. And I remembered him, even back then.’1

The memory is etched in Richie Purdy’s mind too, who also featured that day. ‘It was an All-Ireland game up at Mobhi Road on Dublin’s northside – it could’ve been a quarter-final or a semi-final – and there was this tiny little fella. Rockmount had a really good side at the time but he was the standout. His aggression was unbelievable. He was whingeing and kicking. So he hasn’t changed much. Then I met him again at Ireland trials, but he didn’t get picked because he was too small and that was a bit of a shock.’2

At Rockmount, the coaches had famously called Keane ‘The Boilerman’. The guy who got things going. The playmaker. But there was another alias too, owing to just how diminutive he was.

‘His nickname was The Dot. A full stop, like,’ says Noel Spillane, the long-time soccer correspondent for Cork’s Evening Echo and Examiner newspapers, who covered Keane’s ascent in detail. ‘That’s what the lads would say during the games. “Give it to The Dot.” That’s what he was known as.’3

Keane was aware of his physical shortcomings, but that was out of his hands. So he turned a laser-focus to things he could control: fitness, proficiency on the ball and a dedication to the game that seemed out of sync with the moodiness and restless energy of hormonal teenage years.

‘A few years after first playing against him, there was a week’s camp at The King’s Hospital in Dublin and Roy was part of the Cork group invited to attend,’ Tommy Dunne says. ‘There were two things that stand out. He might talk now about hard work and attitude and how it’s not about technical ability, but at that time, Roy won the award for most technical player in our age-group. And the other thing I remember was that we were a load of young lads away at a camp. The King’s Hospital had dormitories because it was an old Protestant college. We were there in the summertime and, with the exception of one person, everyone was always messing around. That person was Roy. And the reason? He was resting up because the next day was all about training. I’ll never forget it. I used to go into the dorm where the Cork lads were and he was just chilled out.’

Darren Barry was an underage teammate of Keane’s at Rockmount.

‘Gene O’Sullivan, the manager of Rockmount schoolboys for years, and who was a lovely man and who, sadly, didn’t get to see Roy make it, told me one time about him,’ he says. ‘It was the day of Roy’s Confirmation and Rockmount had training. But he still came down to train. He just loved playing that much.’4

Keane did eventually get a call-up to the Irish Under–15 squad for a game against France at Bray’s Carlisle Grounds in June 1987. But he didn’t make the match-day squad, something he’d quickly get used to.

Still, there was a better experience in September, when Keane was named in the Under–16 panel. In a crucial draw with Northern Ireland, he earned an especially rave review and was subsequently included in Joe McGrath’s squad for the European Championships in Spain the following summer.

‘I suppose we will be out there as underdogs,’ coach Maurice Price admitted at the time, before outlining the players he felt could catch the eye. ‘It will be a great opportunity for some of the lads not with English clubs to impress. Paul McCarthy from Rockmount looks to be a terrific prospect and so do Richard Purdy and Jason Byrne.’5

Keane wasn’t afforded a mention but, considering what followed, it was hardly surprising.

In Spain, the Irish team turned in a superb performance and went undefeated in an immensely tough group. They held Portugal, who’d go on to reach the final against the hosts, to a scoreless draw in their opener and then drew 2–2 with Switzerland. Qualification for the semi-finals was still possible heading into their last fixture against Belgium but, despite winning 1–0, the Portuguese did enough in their game against the Swiss to pip Ireland to top spot.

Keane was a spectator for the entire tournament.

From the sixteen-man group, he was one of only two players, the other being the reserve goalkeeper, who saw zero game-time. Even in a brief newspaper report that offered an overview of how the Irish team had fared, he was literally an afterthought: ‘Also in the squad were Roy Keane (Rockmount) and John Connolly (Hillcrest).’6

Purdy remembers Keane’s disgust when McGrath was forced to make changes for the clash with Belgium but still decided against using him. ‘It always sticks out in my memory,’ he says. ‘We had a few injuries after the second game against the Swiss, including myself, so there were some changes for the final fixture against Belgium. I saw Roy’s face in the dressing room when he knew he wasn’t involved and he was like a demon. I remember looking across at him. I knew by his demeanour that he was devastated at not getting a run. And that was our last game because we didn’t qualify for the next stage.’

Keane was badly burned and there’d be plenty of scar tissue. The entire experience – supposedly a proud achievement – was underwhelming.

It didn’t help that, despite the FAI seeing a substantial windfall for the senior team’s historic qualification for the 1988 European Championships, there was a remarkable occurrence before the Under–16s group departed for their own Euro adventure.

In the middle of May, Keane had appeared in The Cork Examiner alongside Downey, McCarthy and Rockmount chairman Jim Deasy. Also in the photograph was Teddy Barry from the New Furniture Centre, the team’s main sponsors. Barry was handing over a cheque to ‘help with expenses’ for the players’ forthcoming trip to Spain.

According to the Evening Herald later that month, the Irish Under–16s had to contribute £40 each towards the cost of their uniforms. ‘We had a very generous sponsorship for both our Under–15s and Under–16s but it is custom and practice to ask the boys to contribute to the cost of such items,’ FAI board member Frank Feery told the paper. ‘The boys were consulted as to the style of clothing and as a result, they looked extremely smart. Just as important, it was Irish-made.’7

Forty-eight hours later, another photograph appeared in the Herald. It was of the entire squad, before they had left for Spain, looking refined in their dark blazers and beige slacks.

‘The Republic of Ireland Under–16 side kitted out in their Castle Knitwear,’ the accompanying caption read.

It was PR fluff and, inevitably, Keane is front-row and glum.

‘The FAI were a joke,’ Purdy says. ‘They’d give us tracksuits to wear if we were playing games or at tournaments, but we’d have to take them off in airport toilets and hand them back.’

By the start of the 1988/89 domestic season, it seemed everyone was moving on and stepping up. Price was right about the Euros acting as a shop window for some of the Irish underage group. Alan O’Sullivan had signed for Luton Town and McCarthy was picked up by Brighton, along with Derek McGrath. Selected for Maurice Setters’ Irish youth squad, Keane was now envious of those around him. David Collins was already appearing for Liverpool’s reserves. The likes of Kieran Toal (Manchester United), Jason Byrne (Huddersfield) and Paul Byrne (Oxford) were all cross-channel too.

The steady migration of his peers was harming Keane’s progress.

In October 1988 the Cork Gaelic football team lost an All-Ireland final replay to Meath at Croke Park by a point. A few days later, Keane would feel a similar sense of bitterness.

‘At last, Cork people have something to smile about,’ went the GAA-inspired opening line of an Irish Press report on the Ireland youths’ win over Iceland in their first European Championship qualifier.8

But the reference wasn’t to Keane. It was to O’Sullivan, who scored twice in the space of four minutes at Dalymount Park. Keane had been named in the initial twenty-two-man squad but failed to even make the bench for the game. Meanwhile, his Rockmount teammate Downey suffered ignominy too, being replaced after half an hour.

When Setters later named an eighteen-man group for a winter tournament in Israel at the end of the year, McCarthy went, O’Sullivan went and even Downey went. Keane was ignored completely.

From the seven home-based players included in the squad, six were from Dublin.

The usual.

Cherry Orchard.

Home Farm.

Belvedere.

For Keane, it was embarrassing. It hadn’t been long since some glittering newspaper reports described how he’d ‘shone in midfield’ in the Under–16 Euro qualifier against Northern Ireland. Now, still stuck at Rockmount, he was being left behind.

There was a pattern. The perception seemed to be that he was good but not good enough. Turning the corner into 1989, there seemed a genuine chance that he could just slip through the net.

McCarthy, through his father, tried to engineer a trial for Keane at Brighton but, mysteriously, it never materialised as the same well-worn excuses were wheeled out.

‘The night before I was due to leave, Paul called to say the trial was off,’ Keane said years later.9

McCarthy went into more detail when he appeared in the RTÉ documentary Have Boots, Will Travel in 1997, which charted Keane’s rise.10

‘He was a very small young fella,’ McCarthy recalled. ‘If you saw a picture of him when he was fifteen, you’d never think it was the same fella. A lot of scouts would have looked at him, seen the size of him and that would’ve put them off. He was meant to come over to Brighton – my dad set it up. But in the end the Irish scout put the Brighton manager off it because he questioned his temperament and his size. But his ability was unbelievable. He never gave the ball away. He scored a lot of goals. He was only tiny, but he’d never be knocked off the ball and if there was any trouble, he’d be there and would never back away from anything.’

Decades later, Harry Redknapp alleged a different version of the story. He detailed a second-hand yarn – passed on to him by a pal – of how then-Brighton manager Barry Lloyd had agreed to watch Keane play in an Ireland youth international upon a recommendation from an unnamed scout.

‘The scout went to see the [Ireland] schools manager and explained the situation – that this was Roy’s big break and he could become an apprentice at Brighton if they liked the look of him,’ Redknapp writes in A Man Walks On To A Pitch: Stories from a Life in Football. ‘“He’s been in every squad but he hasn’t played a minute of any game,” he [the scout] said. “Can you make sure he’s involved on Tuesday?” The coach said no. “We’re not here to showcase kids, we’re here to win football matches,” he said. Keane never played and Brighton didn’t take him.’11

The scout in question was Brian Brophy, who offers up a slightly different version of events.

‘The Under–16s had qualified for the European Championships and Barry [Lloyd] asked me to go over to Spain to have a look at Roy,’ Brophy says. ‘So myself and two representatives from Brighton – their youth officer, Ted Streeter, and youth coach, Colin Woffinden – turned up. The first game was against Portugal and he didn’t play. Then it was Switzerland and he didn’t play. And the third game was against Belgium and he wasn’t playing. We had gone there purposely to watch him. And we were probably the only club out there. We already had Paul McCarthy and Derek McGrath, and Brian McKenna’s parents wanted him to do his Leaving Cert before joining us, so he stayed in Dublin for a while longer. Anyway, we approached Joe [McGrath] and asked him to put Roy on. And he said, “No, no. He’s not good enough.” And we said, “Look, we’ve come all this way.” But, he never played. Roy and the sub goalkeeper, John Connolly, never got on the pitch.’12

Brophy continues, ‘With regards to the story of Paul McCarthy’s father arranging for Roy to go for a trial, I didn’t know anything about it. So I wouldn’t have been in a position to tell Brighton, “No, don’t take him.” I don’t know if it was genuine or if somebody else had arranged it or what happened. But it certainly had nothing to do with me.’

According to Ted Streeter, his motivation for going to Bilbao was to watch McGrath and McCarthy, Brighton’s two recent acquisitions.

‘I hadn’t heard anything about Roy,’ he says. ‘Obviously with his boy having joined us, Joe [McGrath] was keeping an eye on some of the [Irish] lads. But he never mentioned Roy. He was quite small and Joe never recommended him. So Roy was just another member of their squad. We thought Joe just didn’t fancy him and that’s why he didn’t play him. If I had seen him and fancied him, I would’ve made arrangements for Roy to come over. I don’t judge a player on their size and Derek [McGrath] was quite small. So there was no follow-up from me. Also, I certainly don’t remember offering Roy a trial at Brighton and then cancelling it afterwards. I wouldn’t ever call off a trial anyhow. So that wasn’t me. Unless something had been done through Barry Lloyd, the manager.’

Lloyd shatters the myth a little.

‘I don’t think we were even close to bringing Roy over,’ he admits. ‘I was told he wasn’t the biggest and it’s a real difficult one for me. History says we missed out on him, but that’s the name of the game, isn’t it? And in some respects we were happy in our ways because we brought a few boys over from Ireland in that era.’13

And the trial that never was. Does it ring a bell?

‘No, not at all. In principle, we travel to see the player in their own environment. We find it more beneficial than the player being amongst a group of boys they don’t know.’

Those at Rockmount remained perplexed by Keane’s continued absence from the Irish team and his inability to land a trial with a cross-channel club.

‘It was bizarre,’ says Darren Barry, Keane’s midfield partner at Rockmount for three seasons. ‘It was bizarre that he wasn’t being picked up by English clubs because other players in Cork were. He captained the Cork Under–14 Kennedy Cup team that destroyed Dublin in the semi-finals and then went on to win the national trophy. Therefore, they were the best team in the country and Roy was the skipper. Rockmount were one of the best teams in Ireland at the time too. So he was well known to everyone. Anybody who saw him play at that time would have said he could play professionally, without a doubt.

‘It would certainly have been discussed by players, parents and anyone who was watching that Roy wasn’t getting the rewards that his talents deserved. Alan O’Sullivan was a magnificent schoolboy player and probably the best in our team. But people were putting Roy’s name forward to the Luton scout, who was Eddie Corcoran. But he said Roy was too small, which was ridiculous. Regardless of his size, he was still outstanding. I remember in an Under–15 game, he scored a goal very similar to the one he got in Turin for Manchester United in the Champions League semi-final in 1999. He wasn’t very big but he rose up above everyone and headed it across. You rarely saw that at schoolboy level – a player heading the ball like that and particularly somebody who wasn’t tall. It was purely based on timing and rising to meet the ball. He had no height advantage. So I’d seen him do that and knew he was that good in the air even then.’

‘Clubs in England kept giving him the excuse that it was his height, because he was four foot nothing when he was fifteen,’ says Jamie Cullimore, who played alongside Keane in the Kennedy Cup team and faced him constantly at club level. ‘I’ve no doubt it played on his mind. I don’t think it sat very well with him because there was a fight in him from day one. A fifty–fifty header and he’d win it every time and he was half the size of me. It was in him. His timing was superb, his leap. And I don’t remember him ever getting a smack either because his timing was so good. I had about six inches on him when I was underage and I don’t think I ever won a header against him. And it was that attitude. Nothing was going to stop him getting to where he wanted to be. Full stop. He was tenacious.’14

But the local support mattered little, and by the summer Keane was despondent. The season had started with international involvement but that evaporated quickly.

When the Irish youth team beat Northern Ireland in a May friendly, O’Sullivan and McCarthy were both involved, but Keane, snubbed again, was back in Cork instead. A few days earlier, he and Downey featured in the Munster Youth Cup final for Rockmount at Turner’s Cross. They came from behind twice to draw 2–2 with Limerick City.

Another replay.

Typical.

And, as the Irish underage group was beating Malta in a crucial Euro qualifier at Dalymount Park at the end of the month, Keane’s focus was on something a little lower-key. On the June Bank Holiday Monday, Rockmount traipsed down to the old Priory Park to face Limerick again. They lost in a dramatic penalty shoot-out.

Another season over, another year gone and Keane was right where he had started. The local team. Small time.

***

Desperately in need of a reset that summer of 1989, the League of Ireland offered Keane a chance of better exposure and some extra cash. Rockmount, whose senior side played in the Munster Senior League, could provide neither. Approaching his eighteenth birthday, it wasn’t a difficult decision.

And when Brian Carey signed for Manchester United from Premier Division side Cork City that summer, it proved to Keane that maybe it wasn’t too late. Carey had never even featured at underage level for the Republic of Ireland. He’d grafted in the local leagues and enrolled in college to study construction economics, impressing as a commanding centre-half when City came calling. He was getting a high-profile move at twenty-one, and there had been plenty of other interest too, from the likes of Celtic and Arsenal.

By late June, it seemed Keane would be a Cork City player too and a report in The Cork Examiner detailed how he, Downey and another young prospect, Fergus O’Donoghue, had all agreed terms. But then everything went quiet and for good reason.

There are many local myths regarding Keane, and two pertain to how Cork City managed to squander his signing. One version is that a City employee failed to make it to the post office in time one Friday afternoon to send Keane’s documentation to the League of Ireland headquarters. The other is that instead of posting Keane’s application to Dublin as soon as he signed it, City waited until they had Downey’s and O’Donoghue’s too and could send all three in the same envelope.

‘For a 28p stamp, Cork lost a potential star,’ TheIrish Press claimed later.15

The truth? ‘It was just one of those things,’ said then-City secretary Seamus Casey afterwards. ‘I decided to wait until July 1 to send it off. I was trying to be businesslike.’16 It wouldn’t have been an issue if City were Keane’s only suitor, but unbeknownst to them, Cobh Ramblers were also claiming Keane as their player and managed to submit their paperwork before the weekend. It was a sliding doors moment. And considering another crucial administrative occurrence later in Keane’s career when Blackburn Rovers attempted to complete his transfer from Nottingham Forest in the summer of 1993, quite the coincidence.17

In his first autobiography, Keane says he completed a form committing himself to Cork City and that Cobh Ramblers, who played in the League of Ireland’s second tier, only came in for him afterwards. ‘Cork City hadn’t bothered to send the form I’d signed,’ Keane wrote, simplifying the entire episode.18

In reality, it was messier than that and contrasted significantly with what Cobh would eventually tell the league.

The stand-off between Ramblers and City over Keane actually continued into February of the following year, when his first league campaign with Cobh was inching close to completion. Described as a ‘transfer wrangle’ and an ‘ongoing saga’ in the local press, there was even a meeting arranged involving the clubs, League of Ireland officials and Keane himself to find a satisfactory resolution. According to the report, City wanted a ‘substantial fee’ as compensation. But John Meade, the Ramblers’ secretary, maintained that Keane had signed for them earlier in the summer and then subsequently signed for City too. More importantly, Cobh argued, they were first to register Keane with the league.

Still, City were the bigger club. They played top-flight football. They had reached the FAI Cup final the previous season and, despite their loss at Dalymount Park in the replay to Derry City that day, still qualified for another European competition. Earlier in the 1989/90 campaign, they’d faced Torpedo Moscow in the first round of the Cup Winners’ Cup and, though they were ripped to shreds over two legs, it was clear they were operating at a different level to Ramblers. With Carey having secured a move to England owing to his performances for City, maybe more cross-channel teams would be monitoring Noel O’Mahony’s side? If Keane was looking for a platform, City presented him with the biggest one. But, despite all of that, despite having to repeatedly trek all the way from the city to a small harbour town and back again, despite his close friend Downey already being at Cork City, Keane didn’t appear too interested and seemed stung that City had been so flippant regarding the administrative side of things.

When The Cork Examiner reported on Keane’s situation, the final line was short, simple but revealing.

‘It’s understood that Keane wants to continue playing with Cobh Ramblers.’19

It really was that simple. Cobh had been good to him. They wanted him. They’d never messed him around. And by February 1990 – unlike Downey at City – he was playing regularly at an elite level. And making that step up had been his biggest motivation to walk away from a club he’d been at since he was eight years old.

‘He loved Rockmount and he could’ve joined their senior team at eighteen,’ says Jamie Cullimore. ‘But already he was looking to push himself at a higher level. He said goodbye to all of his buddies to go down and play with Ramblers.’

Cobh had got the deal done through youth coach and local carpenter Eddie O’Rourke, who’d been mesmerised by Keane the first time he watched him play in 1985.

‘I never in my life saw anything like him,’ O’Rourke said later, speaking in exalted terms about the rampaging ‘dot’ who consistently inflicted so much damage upon various local teams, including Cobh youth club Springfield. ‘It was like looking at a salmon. He would leap to head the ball from his own area; next minute he’d be up the other end making the final pass. I made up my mind that if ever I got the job as youth manager with Cobh, I’d go after him.’20

He succeeded and Keane was quickly promoted to the senior team for a high-profile pre-season friendly against West Bromwich Albion at St Colman’s Park, where there were a couple of familiar faces in the home dressing room that calmed any nerves.

One was Cullimore, who’d battled Keane many times while at Springfield, was a teammate on the Kennedy Cup side and had also been called into Ireland underage squads. The other was Keane’s older brother, Denis, a gifted local player for Temple United, who was being courted by Cobh boss Alfie Hale. The fixture against the Baggies was his audition and he passed with flying colours.

‘Denis was Man of the Match every second week for Temple,’ Noel Spillane says. ‘Regarding natural talent, he had more than Roy. He’d go past four or five fellas, nutmeg the keeper and back-heel it into the net. But he just had no interest in training.’

Keane’s debut was solid and largely uneventful against a Baggies side that were on a three-game tour of Ireland. A few days earlier, they’d knocked four past Shelbourne at Tolka Park and they did the same down south. Some footage remains of Keane from that evening, scampering down the right side as Cobh break quickly on a counter-attack. Wearing number eight on his back, it’s unmistakably Keane: the running style, the gait, the speed.

In front of a thousand-strong crowd, Cobh put some respectability on the scoresheet with two goals of their own, Cullimore grabbing the second. For the guests, one of theirs came courtesy of Gary Robson, younger brother of Bryan – the player Keane would effectively replace at Manchester United.

Keane went close on two separate occasions, ensuring some mentions in the local press reports the following day. But, in keeping with the sibling rivalry, his big moment was usurped.

‘Denis came down for the game and they gave him the Man of the Match award, but I’d have given it to Roy,’ Cullimore says. ‘I think they were eager to hold on to Denis by giving it to him. He was a class act, but you knew Roy’s heart and soul was in soccer and I was never convinced Denis’ was. He’d play the ninety minutes, but after that he was out gallivanting with the boys. Roy was happy to do that too, but you felt soccer was always in the back of his mind.

‘It sounds really silly saying it, but I always knew there was something special about him. Even underage. At Under–14s he was the smallest fella on the pitch, but he was still our captain. He was thinking faster than other people. When he chested the ball, it was into space. As young fellas you didn’t do that. You chested it and just made sure you controlled it. I was playing for Springfield against Rockmount one day and offside was pretty big in the game back in the eighties, obviously. He was coming at us and there was about five of us in a line. And we were like, “Nah, we’ll catch him offside if he tries to play one of the boys in.” But all he did was dink the ball over the five of us, ran around us and buried the fucking thing in the net. He was a small bit cuter. He always had something that would drive him on further.

‘After a game, he’d let you know that he’d won the dual between you and him. There was this constant fight, no matter who he was playing against, that he was going to win that battle.’

2All Out In The Open

It was January 1988 when The Economist surveyed Ireland for their latest issue. The headline was ‘Poorest of the rich’ and carried a Dickensian photograph of a woman with a child begging on the streets. The magazine detailed the dereliction, social decay and forecast an immensely bleak future.

They were right.

By the end of the year, Anglo-Irish relations were at an all-time low, as Taoiseach Charles Haughey and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher had clashed repeatedly in private meetings. One hundred and four people had lost their lives in The Troubles – the highest number of fatalities since 1982. The unemployment rate was over sixteen per cent while 60,000 people emigrated.

There seemed an air of weary resignation.

The melancholy had a wider cultural resonance too. This was the era when contemporary laments were chart successes in Ireland. Jim McCann sang about Grace Gifford, the forgotten wife of Joseph Mary Plunkett, the youngest of the 1916 revolutionary leaders. Both The Wolfe Tones and Dublin City Ramblers had simultaneous top-ten hits with ‘Flight of Earls’, an ode to an entire generation’s forced departure. And Jimmy MacCarthy’s ‘As I Leave Behind Neidin’, a song about parting lovers, carried that haunting, desperate, metaphorical refrain of ‘Won’t you remember me?’

‘The Irish Rover’, an age-old folk song, was given a rebirth too as The Pogues partnered with The Dubliners for a number one single. The country seemed stuck between the past and present, probably because the future seemed so out of reach.

An RTÉ television news report looked deeper into the mass exodus and spoke to a group of young men heading to England in search of work.

‘Are you trained in any particular skills, lads?’ they were asked.

‘No, none whatsoever.’1

Also in 1988, a government initiative had been announced: Foras Áiseanna Saothair, or FÁS. Effectively, it was a state training agency put in place to try and stem the bleeding as Ireland buckled under the stress of economic collapse. FÁStranslates as ‘growth’ and the organisation’s purpose was to provide people on the unemployment register – in particular those in their late teens and early twenties – with educational courses and schemes that could subsequently better their chances of finding a job.

It wasn’t a radically new idea. Before it, there had been An Chomhairle Oiliúna (The Training Council), or AnCo for short. Still, it was a rebranding exercise that enabled the Fianna Fáil government to show they were tackling a devastating social problem and not simply paying it lip service.

Enrolling in FÁSmeant coming off social welfare and walking into a classroom. But some felt it was a smokescreen, that those in power were merely fiddling the numbers to make themselves look better.

After a multitude of FÁS schemes were announced for East Cork in the summer of 1989, one local Fine Gael politician, Paul Bradford, likened the strategy to putting band aids on the Titanic.

Roy Keane later described FÁSas ‘one part well-meaning, three parts cynical’, but, regardless, it proved a seismic experience for him.

In late June 1989 two jobs were advertised in a variety of national newspapers. Under the name Football Apprenticeship Programme, the full-time roles for Programme Director and Assistant Programme Director were outlined and applicants were encouraged to send their details to the League of Ireland offices at Dublin’s Merrion Square.

The Cork Examiner filled in some blanks and in a brief report on the pending scheme revealed that every League of Ireland club would be entitled to nominate one of their players to take part in what was a full-time training opportunity.

FÁSwould offer a nominal weekly payment plus expenses and, given the fact that the best young players in the country were either first-team squad members or on the cusp of a breakthrough, it meant two separate football incomes. It wasn’t much, but it was certainly better than the dole queue.

By mid-August, the programme was officially launched at an event in Dublin. Maurice Price, one of Keane’s underage coaches at international level, was unveiled as the director, and Larry Mahony, then in charge of St Joseph’s Boys, confirmed as his assistant. Overseeing everything on behalf of the FAI was another figure Keane knew well, the national team manager of Ireland’s Under–16s, Joe McGrath.

‘We’re breaking new ground,’ said League of Ireland president, Enda McGuill, at the time. ‘While the benefit may not be immediately evident, I’m certain the long-term effects will be of tremendous importance in the development of the game in this country.’2

A report in the Sunday Independent described the course as McGrath’s ‘brainchild’ and added it incorporated ‘the best features of the English YTS scheme with some improvements’.3

TheIrish Press went into more detail: ‘The objectives of the scheme, which will operate initially for a year, are to provide opportunities for young players to receive full-time training in their own country – in addition to bringing about an improvement in players’ technical skills, plus the chance to obtain a basic education, including acquiring a foreign language and experience in technology and computer programming.

‘The duration of the programme is forty-eight weeks and players interested in the scheme should be between sixteen and twenty. Players joining the scheme from provincial clubs will live in approved accommodation in the Palmerstown area, while the participants will be given the standard FÁS allowances.

‘Clubs with players taking advantage of the scheme are expected to contribute nominally to the running costs and development of the programme.’4

The initial idea of each League of Ireland club – from both the Premier and First Divisions – enrolling one young player quickly changed. Reigning champions Derry City, as well as the likes of Shamrock Rovers, didn’t take up the offer. So, Cobh Ramblers, Cork City, Drogheda United, Finn Harps, Home Farm and Shelbourne all secured two representatives.

In total, twenty players were selected for the finalised group, including two Republic of Ireland Under–21 internationals, Pat Fenlon and Tommy Fitzgerald, who’d been at Chelsea and Tottenham respectively but failed to make the grade. Others, such as Tony Gorman, who’d had an unsuccessful stint at Mansfield Town and returned to sign for Finn Harps, were in a similar boat.

Keane was part of a Cork foursome. Aware of the course starting in the autumn, he had told Ramblers prior to arriving that if they secured him a place, he’d join.

‘The deal was if I got him on the course, he’d sign. That clinched it,’ Eddie O’Rourke later confirmed. ‘Roy was desperate to go.’

Alongside him was his Cobh teammate Jamie Cullimore, while representing Cork City were Keane’s long-time pal Len Downey and goalkeeper John Donegan. There were other familiar faces too, including Tommy Dunne and Richie Purdy, the latter having featured in Irish squads with Keane.

The start date was set for Monday 4 September, and the day before, Keane was in Ballybofey for a First Division season opener against Finn Harps. Ramblers were fortunate to only come away with a 3–1 defeat, as midfielder Tony Gorman missed a first-half penalty for the hosts.

Afterwards, Gorman headed for Dublin to get settled before the FÁScourse began. He was glad of the victory over Ramblers and especially pleased with having got one over on their mouthy midfielder who was on his case for the entire afternoon.

It was the first time he’d ever met Roy Keane. And his second meeting with him happened a lot sooner than he expected.

‘We had a right battle,’ Gorman says. ‘We kicked each other, had a few unpleasant things to say to each other. There was a lot of effing. He was this and I was that. I was gonna kill him and he was gonna kill me. After I missed the penalty, he was in my face. To arrive into Dublin the following day and one of the first people you see is the guy you were in combat with the day before … You just thought, “Jesus, not him.”

‘We probably didn’t speak all week. When we finally got talking, I told him Cobh’s best player was their left-winger, who turned out to be his brother, Denis! Technically, he was really good and skilful and had a bit of pace about him, and I suppose, at that time, Denis looked the better Keane.’5

Gorman remembers plenty about that first interaction in Finn Park, but mainly the insults. They continued during the course too. ‘Langer was the obvious one,’ he says. ‘We heard langer a hundred times a day down there [in Palmerstown], between the whole lot of the Cork lads. And d’you know what? I think we started using it ourselves. We’d come back to Donegal and call people langers.

‘It was a difficult game against him. Tough. He was quick. He was very good in the air. He was competitive. Some people might say, “We knew he was going to be this or that”, but you couldn’t have judged from that game. First impressions were that he was physical, a really athletic player and a tough opponent. He had a skinny upper body but I thought his legs were quite big. It was Adidas gear that Cobh had at the time and the shorts were the real eighties kind where they’d cut the balls off you and were really tight. For somebody who I thought was light, he was still incredibly strong, mainly because he was so bloody competitive.’

The FÁS course was ritualistic. The Cork contingent would all meet at Kent Station early on a Monday morning for the train to Dublin. Cullimore, music-obsessed and a budding singer/songwriter, would bring his guitar.

‘The Monday morning blues just to get you in the right frame of mind to go up to the second capital,’ says John Donegan. ‘And c’mere, who doesn’t like a good sing-song?’6

From Dublin city centre, they’d hop a bus to Palmerstown, walk down the back of Stewarts Hospital and get things started.

With the players involved in club games the previous day and so many of them spending the morning commuting to Dublin, Mondays were usually quite light, but it was a 9 a.m. start for the rest of the week. Because it was a FÁSscheme, the group also had academic commitments, so on Tuesday and Thursday afternoons they’d head for classes, where the curriculum was certainly unique.

‘We probably did about two hours each day,’ Gorman says. ‘We did English and we studied Spanish too, don’t ask me why. There was a computer class where we did some basic typing as well. But I remember the book we studied in English class was To Kill A Mockingbird. I actually enjoyed it so much, and what we were doing, that I went and got a copy myself because we were only getting through a chapter at a time and I couldn’t wait to get to the end of it. We had to read passages in front of everyone and I remember thinking, “Atticus Finch – what a brilliant name.” But we didn’t have any tests or anything.

‘One day, some lad came into us to talk about sex. There was a banana and a condom. It was one of those moments where all the stupid questions started. “How long does it take?” and all of that. So my two abiding memories of the FÁScourse are To Kill A Mockingbird and some lad shoving a condom over the top of a banana.’

Dunne remembers the classroom stints for a different reason. ‘We used to walk from Palmerstown to Collinstown College, which is a decent stretch. And we used to all have these shell-suits on us. They were black but had pink and white and blue on them. We looked like something getting off the latest fucking spaceship, like the Discovery. We went into class and we all hated it, but we did have some great characters. There was a guy called Mick Wilson who was from Monaghan, and he was mad. The Liffey ran by where we trained at Stewarts Hospital and any of the balls that went into the river, he’d take off all his gear but leave his boots on and dive straight in to get them. There could’ve been anything in there. He didn’t even know the depth of it but was head-first into it.’

‘Those tracksuits were like something you’d wear to a rave,’ according to Purdy. ‘We were like a load of drug dealers walking around Neilstown. How we didn’t get mugged I’ll never know. I think Stewarts Hospital actually got robbed one day by some kid and he still left all the tracksuits behind. That shows you how bad they were. Absolutely desperate.’

The coaching staff felt differently. ‘The tracksuits were the best of swag at that time,’ says Larry Mahony, defiantly. ‘It was the best of gear they had. It was shiny but everyone was wearing that style.’7

Returning to a classroom brought out an anxiety in Keane and he tried his best to skip the mandatory lessons, regardless of the consequences.

‘Roy was a quiet, shy young man in the senior Cobh dressing room and, to be fair, it was a daunting place for an eighteen-year-old as there were a few “less-than-shy” characters already in there,’ says Fergus McDaid, an experienced member of the Ramblers squad. ‘Liam [McMahon], who was in charge by that stage, had received the usual monthly report from Dublin on Roy’s progress. There was no difficulty with ability, effort, performance, etc. Roy was applying himself fully in every sense. But there was an issue with an academic element: attending classes. So, Liam deftly employed the schoolteacher – me – to address this issue with the allegedly reluctant student. When I broached the subject with Roy, the coyness and shyness disappeared. He left me in no doubt as to where his ambitions lay. English First Division football was what he wanted. Academic pursuits were not for Roy and were never mentioned again! Next conversation …’8

Much to his shame, Keane had failed his Intermediate Certificate, and he later admitted that he felt he’d let his parents down as a result. Having just turned eighteen – the age when so many other teenagers were college-bound and taking the first steps towards the rest of their lives – there was some trepidation, perhaps even a fear, of his own future. He’d dedicated himself to football and for what? Some underage caps? He put on a good show but seemed concerned about what was next. One Monday morning, as the train pulled out of Kent Station on its way to Dublin, Keane caught a glimpse of his possible future.

‘We passed a load of workers on the side of the railway tracks,’ Cullimore remembers. ‘And Roy says, “Look at them fuckers out there and they’re going like the hammers. I have to make it as a footballer.” He knew the brains weren’t there, in that way, so he had to make it at soccer. He put everything into trying to make it. In Palmerstown, we’d have to walk to get to our classes and Roy would be like a dog. He didn’t want to go near computers or have anything to do with them. During the class, Roy would turn his off in front of the teacher and just say, “I don’t want to do it, I don’t want anything to do with it.” But that was Roy. All he wanted to do was play ball. “I don’t want to know about computers.” That’s just how headstrong he was when it came to soccer.’

John Donegan, who’d sit alongside him every Monday morning on the way to Dublin, picked up on the single-mindedness too. ‘The fellas working outside on the train tracks had no meaning for him, other than he knew he didn’t want to be there,’ he says. ‘There was only soccer. There wasn’t a case of him having a job. There wasn’t a case of him doing anything else. This was his path. He was well known on the way up but got overlooked. And this was another platform for him. He grabbed it. He said, “I’m going to do it.” And he did it. Growing up, school for Roy was probably the same as that computer course in Collinstown College – he just didn’t want to be there. He probably felt he could’ve been doing something better, like playing ball.’

Still, Keane had carried that determination and hunger for years and knew from previous setbacks that it wasn’t necessarily enough. He admitted to Gorman that watching his former teammates get opportunities in England while he remained at Rockmount was a tough swallow.

‘I remember him saying he’d had a few disappointments where lads were going on trials, like Paul McCarthy and Alan O’Sullivan, and he’d come to a junction in the road,’ Gorman says. ‘There was a road leading him to GAA and another one towards boxing, but he chose the one leading to football and he was going to give it a go. Where other fellas at thirteen or fourteen would still have been playing different sports, he made the choice to concentrate on football.’

The FÁScourse became Keane’s obsession. It was intense. It was full-time. It was draining. But there was a feeling of accomplishment. Under Price and Mahony, the training was technical and challenging. Regular games against local teams were uncompromising. The gym work ensured he was building himself up. He had never been as fit and strong, and a growth spurt finally added some inches to his frame. He had constant access to a pitch and a ball and he even seemed to consider meal times an inconvenient interruption.

‘We’d have a lunch break for maybe forty-five minutes,’ Cullimore says. ‘But within twenty minutes, Roy had the ball under his arm, was out the door and back down practising free kicks or taking shots. And there wasn’t many guys who would do that – give up their lunch break and start fannying around with the ball. But that’s all he wanted to do.’

Each weekend, Keane was also getting an opportunity to showcase the improvements in his game. However dismal things were at Cobh and however patchy the general standard of First Division football was, it remained an important education. Many of his peers felt it was a more impactful experience than what cross-channel trainees were being exposed to.

‘It wasn’t like you were playing underage soccer,’ Donegan says. ‘When you played, you played. And in the League of Ireland, you had to man up pretty quickly. I’d say that really helped Roy a lot. In my case, Phil Harrington was the keeper at Cork City but got injured just before the start of the season and I played about six league matches. He was still injured when we played Torpedo Moscow, so I was lucky enough to play in a massive European game at just eighteen years of age. And that brought a bit of confidence. Going up to the course, you saw all the good players and you had to do a bit better. But the craic was unbelievable too. So it was really full-time training without the pressure of full-time training. And a lot of boys thrived on it. Maybe in England it would’ve been a harsher, harder regime, but we worked really hard and enjoyed it as well. There was a good bit of fun in it but we were still going back playing at the highest national level at the weekend.’

Cobh’s early season form was alarming. Prior to the opening-day loss to Gorman and Finn Harps, the domestic campaign had started with three successive August defeats in Group A of the Opel League Cup. Away to Kilkenny City, where Keane made his competitive debut alongside Denis, they lost 2–0, but worse was to follow.

A few days later, Keane featured again as Cork City visited St Colman’s Park for what proved a tempestuous local derby and where the eighteen-year-old was reminded of just how unforgiving an environment the League of Ireland was.

The fuse was lit shortly before half-time when City midfielder Mick Conroy, who’d already been booked, was involved in an incident with Cobh’s Ken O’Neill. Referee Pat Kelly decided against taking more action against the ex-Celtic player, and Cobh boss Alfie Hale stormed onto the field to remonstrate. He was subsequently sent to the stands, which fuelled the home side’s sense of injustice.

With the interval approaching, Cobh’s goalkeeper and assistant manager Alex Ludzic – whose mistake earlier in the half resulted in a debut City goal for Cormac Cotter – thumped the ball out of the ground in frustration after Kelly whistled for a City free kick. As Kelly reached for a yellow card, Ludzic unleashed a volley of abuse and was sent off instead. Trudging towards the dressing rooms, Ludzic whipped off his jersey and threw it at Kelly in disgust.

The story made the front page of the following day’s Cork Examiner. ‘Conroy’s tackle was the nearest thing I have seen to physical assault in a football match,’ an incensed Hale told reporters afterwards.9 But, his protestations mattered little and he was handed a four-week dugout ban by the FAI.

By the middle of September, however, Hale had walked away. Based in Waterford and running his own business, the commitment and commute proved too much, so, after a 1–0 away defeat to Sligo Rovers, he stepped aside and Ludzic was promoted to player-coach.