Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

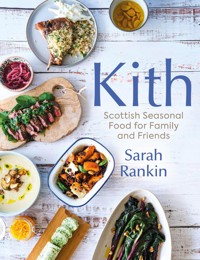

MasterChef finalist Sarah Rankin has a passion for Scottish produce and flavours and for feeding people. Being a food lover encompasses not just a passion for the ingredients themselves, but also for the seasons and weather which nurture them, and the people who tend, harvest and prepare them. Taking those ingredients and creating something delicious for those you love is the highest compliment you can pay any vegetable, beast, fish or fowl. In Kith, Sarah shares stories on her family favourites, the inspiration for her recipes, and why food is the greatest way to show your love. Kith is a collection of practical and inviting seasonal dishes, mixing the traditional and the contemporary, and celebrating the extraordinary versatility of Scotland's larder in a hundred recipes: from Grouse with beetroot and cherry, to Arbroath smokie souffle, Squash ravioli with sage butter, and Lemon posset with caramelised white chocolate and oat crumble. It also includes a section of drinks and canapes. The chapter 'Things of Beauty' encompasses brines, pickles, ketchups and a range of other extras that make the food you serve shine a little brighter, and a section named 'Firm Foundations' helps to arm the home cook with a repertoire of sauces, stocks, pastry, bread and pasta, and butters and creams.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 258

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Sarah is a Highlander, now living in Perthshire. After reaching Finals Week on the BBC’s MasterChef in 2021, she began cooking full time. She is now a Supper Club chef, caterer, food writer, broadcaster and culinary event host, and can be found regularly on the food festival circuit around the UK.

Sarah’s passion is seasonal Scottish food, and her recipes celebrate Scotland’s larder and the wonderful producers who nurture it.

First published in 2024 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Sarah Rankin 2024

Photography by Katie Pryde, 2024www.katieprydephotography.co.uk

The right of Sarah Rankin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78027 836 0

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Mark Blackadder

Papers used by Birlinn are from well-managed forests and other responsible sources

Printed and bound by PNB, Latvia.

To my Kith.

They are many in number and have inspired me in a hundred different ways.

Mum and Granny, who proved that the best food is food made with love.

Dad, who showed us that with hard work anything is possible. And that you can still claim you made dinner if all you did was stir.

My children, who have unknowingly been testing recipes all their lives, their critique unflinching.

The Birds, who have always had my back, but have the palates of savages.

But mostly, to Mr SRC, who quietly clears up the devastation I wreak in the kitchen, and in life. And is prouder of me than I deserve.

Contents

Introduction

Housekeeping

Firm Foundations

SPRING

SUMMER

AUTUMN

WINTER

Bits & Drinks

Things of Beauty

Acknowledgements

Index

Introduction

Food is love. For me, it always has been. Whether a swap for a pickled onion Monster Munch with your own-brand ready salted in the playground, or sharing a tasting menu experience somewhere fabulous and Michelin-starred, food is about the people you eat it with just as much as it’s about what you actually eat. My love of food started young. It was humble and of the ’70s and I loved it. Tinned Heinz vegetable salad and thick slices of home-cooked ham on summer weeknights, and tartan flasks of homemade lentil soup on the summits of misty Munros.

Being a food lover encompasses all. Loving the ingredients, of course, but also the seasons – the weather that brought them to you – and the people who tend, harvest and prepare them for you. Treating everything you use in the kitchen with respect is the highest compliment you can pay any vegetable, beast, fish or fowl.

Kith is a collection of seasonal dishes that work perfectly in certain situations – or many – some with an accompanying tale. The story may be about the ingredient: how it was produced, where and by whom. Or about how I came to create the recipe and what it means to me and those I share it with.

Each recipe section lists a range of wonderful produce you are likely to find during that season. I have, of course, left out many of the everyday things, but this in no way diminishes their value or deliciousness.

I’ve tried hard to focus on produce grown in Scotland and the UK first and foremost, or those ingredients synonymous with Scottish and British cooking, as well as throwing in a few forgotten gems in the hope you can help revive them. Bear in mind, of course, that much of our food is imported, so there are many things which, although seasonal, will be available to us all year round. Do your best to buy from local growers wherever you can.

Scotland is my home, and although I have lived elsewhere and am inspired by flavours from everywhere, it is the food and ingredients of Scotland that I turn to most often. Our larder is a bounty, and our land is awash with makers, bakers and artisans who celebrate the best it has to offer. I want to share their stories, shine a light on their products, and spread the word on the wonderful array of delicious things that this great land and its people create. I hope that Kith will do the same.

These are the dishes I love, old and new. The things I cook and eat at home, to share with the people I love or to enjoy in rare moments of solitude. All of the recipes can be easily made for one, two or a houseful. Most can be multiplied when the hordes descend, and where I’ve used game or a very seasonal or hyper-local ingredient, I’ve offered alternatives if those prove hard to find.

I am a glug of this and a handful of that kind of cook, so don’t get too hung up on measurements (except in desserts or baking – there must be no deviation there; this is science, after all), and feel free to switch out any herbs, spices or flavours you don’t enjoy with something you do.

Cooking is, above all, an activity to be savoured. Food, for me, is love. And these recipes are the ones I love the most.

They have at their heart, I hope, a sense of mine.

Housekeeping

Just a few notes on the general rules I’ve stuck to in my recipes. You will no doubt find a host of exceptions, but these are what I set out to live by.

SEASONING

When I say salt, I mean fine sea salt. When I finish a dish with sea salt, I mean good quality sea salt flakes such as Blackthorn or Isle of Skye. For black pepper, always use peppercorns in a grinder, fresh. White pepper, fine and ready ground, is best for white and cheese sauces, where you don't want colour compromised.

BUTTER

British and unsalted, unless salted is stated. Salt burns, so can affect the taste and leave a hint of scorching on the palate. Also, butter manufacturers rarely list the amount or type of salt used, so the cook has no control over the seasoning of the final dish. In baking, particularly, too much salt can toughen the final texture of a sponge or batter, so best to keep control of the volume of salt in any recipe.

EGGS

Medium, unless otherwise stated, and only ever free-range. And, where you can, from somewhere local so you can get the freshest eggs possible. Over 1 million UK households keep hens these days. Make friends with those folks and get access to fresh eggs and good people. Duck eggs are larger – about the equivalent of 2 medium hens’ eggs – and have a richer flavour, so make fabulous pasta and hollandaise.

SPICES

Up to you. Usually, most of those I’ve listed are there for a reason, but if you’ve a particular aversion to one, switch it out or replace it with something you do like. Ditch anything more than about 8 months old if it’s in ground form. Whole spice like coriander seed or cinnamon can last for years. I’m sure I have a small jar of whole nutmegs that came from two houses ago.

If you use a lot of spices, Asian supermarkets offer absolutely the best value, with much larger 500g bags for about the same price as the small glass jar you’ll find in a traditional supermarket.

There are a few pointers that can help if you’re trying to recreate something you’ve tasted but aren’t sure what the exact spices are. I’ve created a little list that might help nudge things in the right direction, but as with all things, be flexible, add what you like and don’t pay too much attention to ‘the rules’.

Middle Eastern dishes tend to use aromatic spices like cumin, saffron, sumac, za’atar, dukkha, cloves, allspice and cinnamon, as well as herbs like mint, parsley and oregano.

South Asian and Indian dishes focus on cumin, coriander (both dried and fresh), chillies, turmeric, cardamom, garam masala, mustard seeds and nigella seeds. Dried whole chillies leave an underlying heat while fresh give a much zingier, brighter spicy hit.

Spanish and Mediterranean foods use paprika (sweet, smoked and picante), fresh parsley, bay and oregano, as well as basil.

British dishes at the traditional end of the spectrum focus on nutmeg, mace and good old black pepper, with herbs like rosemary, sage and thyme for darker proteins, and dill for fish. Tarragon works brilliantly with chicken and fish dishes too.

HERBS

The general rule of thumb is: soft and fresh at the end of a recipe, and woody or dried at the start. I don’t keep a huge number of dried herbs, as I most often use fresh.

Be aware that a dried and fresh version of the same herb will taste completely different, and there are times when dried is preferable. In a dressing for spicy onion relish, for example, I’d choose dried mint over fresh, and soups and stocks are nothing without bay leaves. A pizza sauce or tomato ragu will be lent an air of Mediterranean authenticity with a good whack of dried oregano and marjoram.

If you buy fresh herbs from the supermarket in pots, split them out when you get home. There are generally three or four plants in there to help them look nice and full on the shelves. They are all competing for nutrients in that little space, so split them and you’ll have healthy fresh herbs for weeks to come.

STERILISING

Sterilisation is a step that must not be missed when making pickles, potted meats or anything you are storing in a jar, as harmful – even deadly – bacteria can build up in containers not properly treated.

Wash your jars, lids and seals in hot, soapy water, rinse and leave to dry on kitchen paper.

In a large pan, place an upturned plate on the base and put your jars on top without lids or seals. Fill the pan with cold water so that the jars are covered and bring to the boil. Boil for 10 minutes, then turn off the heat, cover and leave until ready to fill. Start sterilising your containers as close to the time you intend to fill them as possible, so that they remain warm and sterile.

Place your lids and rubber seals into another pan and fill again with cold water until covered. Allow to come to a simmer and keep at a simmer (around 85°C) for 10 minutes. Do not boil, as this will affect the life of your rubber seals. Turn off the heat, cover and leave until ready to fill. Just as with your jars, don’t leave for too long before using.

Before filling, remove the jars, lids and seals carefully with tongs and leave to air dry on kitchen paper. Fill and seal as soon as they are dry.

KIT LIST

The following items will make your life altogether easier. Some are essential, some are nice to have, some are downright luxurious. I shall leave it to you to decide which is which.

You should note that I haven’t listed anything that I don’t actually use. That’s why you won’t find a madeleine tin or an oyster knife, two things which when chatting to a friend about this section they were amazed I didn’t possess!

Knives

I have a very expensive set of 14 knives I requested as a post-MasterChef birthday gift. I use two of them.

Find a good 7-inch chef’s knife, keep it sharp and never put it in the dishwasher. A smaller paring knife can be useful too.

Blenders

I have a bullet blender with two different-sized cups, which can deal with pretty much any job, and a stick blender for everything else. The stick blender was a panic purchase while I was filming MasterChef and practising in my hotel room, and it cost under a tenner. I use it more than the very fancy branded one I had at home, which is nothing like as powerful.

Cheesecloth/muslin

I know this seems ludicrous, but whilst proofing this book I found I had mentioned these 15 times! Great for straining sauces and stocks and making oils. Honestly worth the couple of quid.

Deep-fat fryer

Deeply unfashionable now, but I wouldn’t be without mine. A much safer way to deep fry. With a temperature control, so you never have to guess how brown that cube of bread really is.

Air fryers can work in place of them, but I find that the final results are often drier in texture and you do run the risk of burning. Air fryers cook best at 10–20°C lower than the temperature a standard recipe calls for.

Electric hand whisk

This is so useful and very easy to clean. Whipping cream or egg whites by hand is far too much like hard work.

Food processor

Full disclosure: I have a very expensive, Wi-Fi-enabled, all-singing, all-dancing one. But I managed perfectly well with a standard version until I got this as a gift. One which has chopping, grating and shredding blades is incredibly useful.

Mandolin

I am a cook, not a trained chef. And my knife skills reflect that. Although I can handle a knife pretty well, my extra thinly sliced work is not as consistent as it should be. A mandolin is now a really affordable bit of kit and with it, you’ll take minutes to prep a whole bag of potatoes for dauphinoise. Buy one with a hand guard. And use it.

Non-stick frying pans

I use stainless steel pans in the main, but a good non-stick is essential for pancakes, omelettes and a host of other uses. Buy the best quality you can afford, one small and one large. With rounded sides so you can sauté like a pro and metal handles so they can go from hob to oven.

Pans

Stainless steel are my go-to. I’ve had my current set for at least 20 years. They don’t degrade like non-stick ones and are easy to clean. Go for a set with insulated handles. You’ll need a range of sizes but don’t do without a large stockpot, two medium pans and a small milk pan, all with lids. A non-stick griddle pan is also useful.

Pastry cutters

Useful for biscuits, scones and for using as moulds. I use metal, straight-sided ones, which can go in a pan and be used to make crumpets and fry eggs in perfect circles.

Pestle and mortar

The best tool for making pesto sauces and salsas and for crushing nuts and whole spices.

Tins and trays

I have a very well-seasoned roasting tin from a student flat that I am almost certain I stole; a deep-sided tin that can double up as a bainmarie; a baking sheet for shortbread and biscuits; a square tin for brownies, tablet and fudge; and a bun tin. I also have one round springform tin that I use for cakes and pies. Anything else is a bonus.

Slotted spoons

Metal ones for stainless steel and for working in hot oil, and plastic if you’re using them on non-stick.

Spatula

A heatproof spatula is probably the one thing I cannot manage without in the kitchen. For turning and folding a slow cooked scrambled egg, or scraping the last vestiges from a bowl of cake batter, it’s the tool I reach for first.

Thermometer

This is by far the item I use the most in the kitchen. Brilliant for sugar work and for testing the temperature of hot oil for deep frying. I wouldn’t be without it. I use the Thermapen brand, but there are a huge range out there. I have had little success with the probe style that goes into the protein whilst cooking, and the other that attaches to a reader outside your oven, both having failed pretty quickly.

Wooden spoons

As many as you have space for. I buy in bulk from a major Swedish retailer, as they have a set which includes one with a nice long handle, ideal for larger stock pots.

I once worked in a caterer’s when I was a student – I was not allowed anywhere near the food, other than putting croissants into paper bags, but one of the ladies in the kitchen once scolded another by telling her that leaving her wooden spoon in the pan was simply seasoning the spoon and allowing the gas flame to scorch the handle. I’ve never forgotten it. Never stopped doing it, but never forgotten it.

Other tools

Silicone pastry brush, grater, microplane for zesting citrus or grating garlic and ginger, fish slices, potato peeler for veg and shaving parmesan, sieves of various sizes, casserole dishes and ramekins (charity shops are great for picking these up), wire cooling rack, several hundred tea towels.

CONVERSION TABLES

Firm Foundations

There are a few wee things worth knowing that help any cooking venture go smoothly. An endless supply of tea towels is one (someone to put them to good use is another). The following are a few others that I’d suggest getting on top of to help you get the best out of your time spent in the kitchen.

Sauces

Traditionally in classical cooking there are five mother sauces. Some are well worth knowing and using, but there are a couple that I’ve never had call for, so I’ve listed the sauces I use most below.

Beurre blanc

1 shallot

120ml white wine

50ml white wine vinegar

225g butter

Do not be afraid. Beurre blanc has a reputation of being difficult, but even a split sauce can be recovered with a few drops of hot water. Chop the shallot into what chef types call a ‘brunoise’. This is just a very fine dice created by cutting your shallot in half lengthwise, slicing into julienne, then turning 90 degrees and chopping again. Add 1 tbsp of the shallot to the white wine and the white wine or chardonnay vinegar. Reduce until only about 2 tbsp of liquid remains. You can strain at this point if you want a smooth sauce. Take 225g of cold, cubed butter and whisk in on a low heat. Ensure each cube is emulsified into the vinegar and shallot mixture and looks glossy before adding the next. You must serve this sauce immediately, as cooling and reheating risks splitting. If it does split, a few drops of boiling water may bring it back for you.

Beurre noisette

100g butter

squeeze of lemon or dash of caper brine, to taste

This is the easiest sauce ever and is fantastic with fish. Just melt your butter over a medium high heat, swirling it constantly until it starts to turn brown. Don’t let it go too far, as it will burn and be bitter. Dunk the base of the pan into cold water to stop the cooking. Add a squeeze of lemon or a little caper brine before spooning over pan-fried fish fillets.

Béchamel

50g butter

50g plain flour

500ml whole milk, warmed

sea salt and ground white pepper

nutmeg

This is the base for your cheese sauces, or the key component in an oozing lasagne. Start with the butter melted in a pan on a low heat. Add the plain flour and stir in well to make a roux. Warm the whole milk and add a little at a time to the roux, stirring or whisking to prevent lumps. Warming the milk helps with this, I find. Add salt and white pepper to taste, and grate in a little fresh nutmeg. It’s the all-important nutmeg that takes it from a plain old white sauce to béchamel. Use as is, or add your favourite grated cheese. A good Scottish cheddar-style cheese, or a Swiss Gruyère, have just the right density and moisture content for the perfect oozing, melting texture.

Red wine

1 stick celery

1 small onion

1 small carrot

1 bay leaf

a few springs of thyme

1 garlic clove

½ bottle of red wine

375ml beef stock

1 tbsp demi-glace (optional)

couple of knobs of butter

Learn to whip up a good red wine sauce and you’ll have nailed cooking for ever. I use a mirepoix as a base, which is simply a mix of diced celery, onion and carrot cooked slowly over a low heat to tease out all their natural sweetness. Once the vegetables are soft, I turn up the heat, add a bay leaf, a few sprigs of thyme, a whole garlic clove – which I smash with the flat edge of a knife – and a half bottle of red wine. It is always worth using decent quality wine for cooking. If the flavour is awful, your sauce will be awful, so use a wine you’d be happy to drink. I say this like there is a red wine I’m not happy to drink. As if.

Reduce this down to about half, then add the same amount of beef stock and, for a super-rich finish, a tablespoon of demi-glace (an ultra-reduced veal stock in jelly form). Reduce again until about one third of the volume of liquid remains and the sauce has thickened a little. Strain and return to a clean pan and whisk in a couple of small knobs of butter, one at a time, until the sauce is glossy and thick.

Bordelaise

1 kg beef bones (marrow scooped out, chopped and reserved)

1 litre chicken stock

1 onion, sliced

4 garlic cloves, crushed

a few sprigs of thyme

large glass of white wine

1 shallot

2 tbsp flat leaf parsley

This is a super fancy and super cheffy sauce with quite a long process, but the intense flavour is incredible. Best saved for properly showing off. Ask your butcher for beef bones and bone marrow. You’ll need to scoop out the marrow, then roast the bones (about a kilo of them) in a hot oven for about half an hour. Add those, and all the tray juices, to a large pan with the chicken stock. Bring to the boil, then simmer for 2 hours. Sieve and chill. Once cold, you’ll be able to skim off any fat that rises to the top. Fry off the onion, cloves of crushed garlic and a few thyme sprigs in a little oil. Add the wine and reduce until almost no liquid remains. Add the chilled stock and simmer gently until thickened and shiny-looking, and strain again. When you are ready to serve, add a very finely diced shallot, the finely chopped flat leaf parsley and 1 tbsp of diced bone marrow. Warm a little and serve immediately.

Hollandaise

125g butter

2 egg yolks

½ tsp white wine vinegar

squeeze of lemon juice

This contains artery-furring amounts of butter so is not to be entered into lightly, but there is nothing as good as a banging fresh hollandaise.

Melt the butter. Place the egg yolks into a bowl over a pan of just simmering water. Whisk them well and drizzle in the melted butter slowly. It will start to thicken as the butter and egg emulsifies, and once it reaches the thickness you like pour in the white wine vinegar and check for seasoning. I quite like it on the sharp side so add a quick squeeze of lemon juice too. I have been known to add a shot of sea buckthorn juice in place of the lemon for more tartness and citrussy zing. Use immediately.

Tip: I would not advise using a blender for this as the harshness of the speed often causes the sauce to split.

Béarnaise

1 shallot

50ml tarragon vinegar

2 egg yolks

120g butter, melted

sprig of fresh tarragon

seasoning, to taste

This is similar to the hollandaise recipe, with the addition of tarragon and shallot. It works amazingly well with steak but is equally fabulous for dunking chips into. The anise hit from the tarragon imparts a lovely freshness that tastes like summer. I use this as a dip for asparagus that have been wrapped in Serrano or Parma ham and crisped in the oven. Delicious.

Traditionally, the butter is clarified (melted and then the clear butter is poured off the cloudy milk solids). I have done it both ways and see no difference, so save yourself the extra faff and leave out the clarification.

Chop the shallot and put in a pan with the tarragon vinegar (make your own by adding a couple of sprigs to a bottle of regular white wine vinegar). Add a little water and cook until reduced by half. Strain and set aside to cool. Place the egg yolks in a bowl over a pan of simmering water, add the strained vinegar and whisk until it starts to thicken. Remove from the heat and drizzle in the melted butter very slowly, whisking in each addition until fully emulsified and thickened. Add some fresh tarragon and check for seasoning. Serve immediately.

Stocks

I urge you to make your own stocks wherever possible and try and avoid cubes if you can. Many are full of oddly named or numbered ingredients that can dull the flavour of the fantastic fresh ingredients you’re using with overwhelming saltiness. I find the gel pots you see more often now are a decent tasting and convenient halfway house between homemade and shop-bought liquid stock.

Using your own stock makes all the difference to the flavour of your food. You know exactly what it contains and it cuts down on waste. Freezing chilled stock in freezer bags laid flat is a great way to save space and means you’ll always have a delicious soup or sauce base on hand at a moment’s notice.

I am utterly bewildered by the current trend for ‘bone broth’, spouted as a ‘superfood’ as though it’s something new. My granny made it and so did yours. This is not a phenomenon and you certainly don’t need to buy a wildly expensive branded carton in a chi-chi grocery store to get the same flavour. Simply roast your chicken, chuck in some aromats like bay, half an onion, a leek, a carrot and a few peppercorns. Let it simmer. And Bob is indeed your stock-making uncle.

Chicken stock

To ensure the most flavourful stock, the base ingredients are key. Use either a bag of frozen chicken wings – make sure to use a brand unadulterated with any seasoning – or the carcass from your roast chicken. Throw the wings into a roasting tin with a couple of quartered onions, a bunch of thyme and a bay leaf and season them well. Toss in some vegetable oil to coat and roast them on a very high heat – around 200°C (fan) – for about 20 minutes until well browned. Tip the contents of the tray into a large pan with water, along with a roughly chopped carrot, a couple of ribs of celery, more onion and a few peppercorns.

Deglaze the tin with a little hot water or white wine to ensure you scrape up all the good bits and add that to the pan too. Bring up to a simmer, then cover and cook on very low for about 2½–3 hours, skimming off the top whenever needed. Strain through a very fine sieve or cheesecloth, check for seasoning, then chill. You can skim off any solidified fat, which will rise to the top once completely cooled.

Be sure not to cook for much longer than 3 hours, particularly if using a precooked carcass. If overcooked, the amino acids in the bones can break down too much and impart a bitter flavour from which there is no coming back. It’s also vital that you don’t skip the straining and seasoning. It would be a great shame to spend all that time and effort, only to end up with a cloudy or insipid stock.

Beef stock

Just like with a chicken stock, you can use bones from a cooked joint, but as we’re more likely to use a boneless cut when it comes to beef, ask your butcher for stock bones. Brown them with any trimmings you have from prepping your joint in a tray in the oven, just as with chicken stock.

Then transfer to a pot with roughly chopped onion, carrot, celery, bay, thyme and rosemary. Top up with 1 litre of cold water and bring up to a simmer. I like to leave those working away for about 2 hours to ensure maximum flavour extraction. Skim during the simmering to remove any impurities that rise to the top. Pour through a fine sieve lined with a muslin and then allow to cool. Store in 100ml portions in the freezer.

Demi-glace

This is super cheffy but an absolute game changer when it comes to creating the richest, beefiest base for red meat-based dishes or sauces. It takes a fair bit of time so is a nice weekend project. I certainly wouldn’t be trying to knock this out for a Tuesday night dinner.

2kg veal bones (your butcher will be able to help)

1 large onion, roughly chopped

1 large carrot, roughly chopped

2 celery ribs, roughly chopped

1 bulb of garlic, cut in half

200ml red wine

1 tbsp tomato puree

bunch of thyme

bunch of flat leaf parsley

2 bay leaves

1 tsp whole black peppercorns

2 tbsp dried mushrooms

• • •

Roast your bones in vegetable oil in a hot oven – 200°C (fan) – for about 50 minutes or until well browned. Meantime, add the veg to a pan and brown well in oil. Add the bones when roasted and deglaze the baking tray with a little of the red wine. Add the deglazing liquid and any burnt flavour bombs from the tray to the pan.

Add the tomato puree, herbs and pepper, and the rest of the wine. Bring to the boil and add the dried mushrooms. Simmer and reduce until you are left with about a third of the original volume of liquid.

Add 2 litres of cold water, turn down to a simmer and cook on a low heat for around 6 hours, skimming when necessary.

After 6 hours, turn off the heat and leave to cool. Strain through a fine sieve lined with muslin and return to a clean pan. Boil and then turn down to a simmer for a further 45 minutes or until the liquid has reduced again by half. Cool. This is a super concentrated stock and around 1 or 2 tablespoons will take the flavour of any red meat dish to stratospheric levels. It will keep in the fridge for weeks or in the freezer until the end of time. (Or a year or two.)

Fish stock

Liquid fish stock is tricky to find sometimes and the cubes, I think, bear no relation to a fresh, fragrant homemade version. It’s easy to make your own and is essential in creating a rich sauce to go with your pan-fried fillets or in a creamy fish pie.

If you buy your fish whole, or have dressed crab, keep the shells, bones and heads and freeze them in a large plastic container until you want to make your stock. I often keep langoustine and lobster shells for making intense shellfish bisques.

Add them to a pan with butter and gently heat them. Be very careful not to take them too far; fish bones are delicate things, and burning them will make the stock taste acrid and bitter.