28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

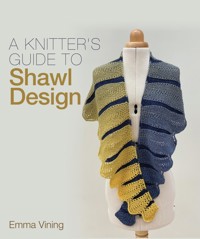

As a desirable item of fashion, a cherished gift or a wardrobe essential, the shawl enjoys enduring popularity among knitters and non-knitters alike. The most admired of these beautiful accessories are designed with inspiration drawn from a wide range of themes and ideas. This creativity is achieved by blending a knitter's imagination with their knowledge of how to translate a source of inspiration into an exciting new design. A Knitter's Guide to Shawl Design will inspire knitters of all levels to personalize their knitting and create original shawl designs. Author Emma Vining describes her own design processes, encouraging readers to explore and experiment with shawl shapes and stitch patterns. Beautifully illustrated with photographs, sketches and explanatory diagrams, this book explores tradition and innovation in shawl design. It demonstrates the effects of yarn, knitting techniques and finishing choices on the end design and considers the framing effect of edges and borders and how to plan these into your project. The geometry of the shawl shape is examined - there are individual chapters on squares, rectangles, triangles, circles, semi-circles and crescents. Finally, the design process is illustrated in full over five detailed case studies, each culminating in a full shawl pattern by built environments.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 292

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

A KNITTER’S GUIDE TO

Shawl Design

A KNITTER’S GUIDE TO

Shawl Design

Emma Vining

First published in 2021 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

© Emma Vining 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 964 8

Cover design: Maggie Mellett

CONTENTS

Abbreviations and Chart Symbols

Introduction

Part 1 SHAWL DESIGN IN CONTEXT

1 Tradition, Innovation and Inspiration

2 Yarn, Tools and Techniques

3 Edgings and Borders

Part 2 INDIVIDUAL SHAWL SHAPES

Introduction

4 Squares

5 Rectangles

6 Triangles

7 Circles and Semicircles

8 Crescents

Part 3 SHAWL PATTERNS

Introduction

9 Riverside Shawl

10 Cardiff Bay Shawl

11 Modernism Shawl

12 Open Doors Shawl

13 Las Setas Shawl

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Index

ABBREVIATIONS AND CHART SYMBOLS

Abbreviations

dec’d: decreased

inc’d: increased

k: knit

k2tog: knit the next two stitches together (1st dec’d)

k2tog-tbl: knit the next two stitches together through the backs of their loops (1st dec’d)

k3tog: knit the next three stitches together (2sts dec’d)

m1 and m1l: make one and make one left – make 1 stitch by bringing the tip of the left-hand needle from front to back under the strand of yarn running between the stitches sitting closest to the tips of the left- and right-hand needles and then knitting through the back of this loop (1st inc’d)

m1r: make one right – make 1 stitch by bringing the tip of the left-hand needle from back to front under the strand of yarn running between the stitches sitting closest to the tips of the left- and right-hand needles and then knitting this loop (1st inc’d)

mrk: stitch marker

p: purl

p2tog: purl the next two stitches together (1st dec’d)

p2tog-tbl: purl the next two stitches together through the backs of their loops (1st dec’d)

p3tog: purl the next three stitches together (2sts dec’d)

patt: pattern, work in pattern

pm: place marker

psso: pass slipped stitch over, often worked as a part of a decrease such as ‘sl1, k2tog, psso’ or ‘sl1, p2tog, psso’

rep: repeat

RS: right side or right-side

sk2po: slip 1st, k2tog, pass slipped st over – slip the next stitch from the left-hand needle to the right-hand needle knitwise, knit the next two stitches together (k2tog), and pass the slipped stitch over the first stitch on the right-hand needle (2sts dec’d)

sl1: slip one stitch (purlwise) – slip the next stitch from the left-hand needle to the right-hand needle purlwise, unless working the slipped stitch as part of a ‘sl1, k2tog, psso’ decrease, in which case slip this stitch knitwise

sl1 wyif: slip one stitch (purlwise) with yarn in front (wyif) – slip the next stitch from the left-hand needle to the right-hand needle purlwise while the yarn is held at the front of the work

sl2: slip two stitches (knitwise) – slip the next 2sts from the left-hand needle to the right-hand needle, one at a time, knitwise

SR(s): short row(s) or short-row

ssk: slip, slip, knit – slip the next 2sts from the left-hand needle to the right-hand needle, one at a time, knitwise; insert the left-hand needle into the fronts of these 2sts at the same time; knit these 2sts together through the backs of their loops (k2tog-tbl) (1st dec’d)

st(s): stitch(es)

w&t: wrap and turn, used with short-row (SR) shaping; a stitch is wrapped to avoid a gap remaining in the knitting where each short row is worked. This wrapping action is known as wrap and turn. To wrap a stitch, knit to the stitch to be wrapped; slip the next stitch purlwise; take the yarn to the back of the work; slip the slipped stitch back to the left-hand needle purlwise without working it; take the yarn to the front of the work; and turn the work. When the wrapped stitch is reached on the subsequent row, work the wrap loop and the wrapped stitch together, to close the gap between the wrapped stitch and the adjacent stitch

WS: wrong side or wrong-side

wyif: with yarn in front

yo: yarn over – take the yarn over the right-hand needle from front to back (1st inc’d)

yo twice: yarn over twice – take the yarn over the right-hand needle twice, and, on the next row, work k1, p1 (or p1, k1, as required for pattern) into the double-yarn-over loop (2sts inc’d)

Table of chart symbols.

INTRODUCTION

As a hand-knitting designer, I am fascinated by pattern. My favourite patterns are inspired by the world around me, from nature to the built environment. I capture my ideas through sketches and photographs and use these to help me design knitting stitch patterns. Shawl design is the perfect framework in which to place my designs and to explore stitch patterning through the creation of a beautiful, wearable accessory. There are several complete knitting patterns in this book, with full explanations of how the designs were developed through my design process. However, there is so much joy to be found in creating and customizing designs to suit your own preferences. I encourage you to experiment and explore. In this book, my aim is to inspire you to look for your own design source material and to help you to translate your designs into personalized shawls that can be worn, gifted and treasured.

Each chapter throughout this book contains my photographs and sketches of inspirational sources. Examples include archive research, architecture, infrastructure and decorative ironwork. These sources are used to develop ideas for shawl shapes and stitch patterns. Alongside the inspiration, practical advice includes instructions detailing how to knit individual shawl shapes, building up to working with complex combinations of multiple shapes and stitch patterns. With the emphasis on design development, each section contains examples of how different factors affect shawl design. For example, choosing a different yarn fibre can transform a design.

In Part 1 of this book, shawl design is put in a historical context, with illustrations from the Knitting and Crochet Guild (KCG) Collection. By taking a close look at shawls knitted in a variety of what can be considered traditional styles, we can see that knitters have always made their own additions and alterations to established design conventions. Building on these fascinating examples, the next section explores a variety of techniques and tools required for knitting shawls, before going on to consider the effect of using different yarn weights and fibres, and to look at options for edgings and borders.

A fundamental building block of shawl design is the overall shape of the shawl. Part 2 uses inspirational photographs and sketches as a way to approach designing shawl shapes. These shapes are illustrated by knitted swatches, with full instructions provided to recreate the swatches. The emphasis of this section is on the design decisions taken into account when planning a shawl project. Beginning with rectangles and squares, this part goes on to explore triangles, circles, semicircles and crescents.

The final part of this book contains five detailed case studies. Each case study includes the initial inspiration, a detailed description of the shawl’s design development and finally the full written knitting pattern. These patterns, and the accompanying images and sketches, along with any of the sections in this book, can be enjoyed as interesting knitting projects. I encourage you to use them as starting points for your own original designs, and I look forward to seeing the results!

Engraving from La Gazette Rose, 15 Octobre 1865, No. 680: Robes et Cachmires, Louis Berlier, after Héloïse Leloir-Colin, 1865, Rijksmuseum Collection (http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.490597).

What is a Shawl?

The first association with the word ‘shawl’ is often ‘christening’, but have you ever come across a ‘tippet’, a ‘wrapper’ or a ‘cloud’? These terms date from Victorian times, and the accompanying incomplete list shows how much variety there can be in design. When considering the origin of the word ‘shawl’ in her book Knitted Shawls and Wraps (1984), Tessa Lorant explains:

The word shawl is derived from the Persian ‘shal’, and was adapted from this into Urdu and other Indian languages. From there it found its way into the European languages in similar forms. However, the term shawl was not in general use in Europe until the end of the seventeenth century, and it did not refer to an article of European dress until almost a century later.

From these early definitions, shawls have developed into extremely popular fashion accessories and even as symbols of status or wealth. Enormous and extremely costly nineteenth-century shawls produced in Paisley, Norwich and Edinburgh were designed to be displayed over the vast, wide skirts fashionable at that time, such as that shown in the accompanying illustration. More recently, Burberry-monogrammed blanket-size ponchos and iconic Hermès silk scarves are instantly recognizable high-fashion accessories.

Shawl with ornamental boteh design, made in Kashmir, France or Great Britain, anonymous, c.1820, Rijksmuseum Collection (http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.28464).

A shawl can also be categorized by the material from which it has been made, the construction method used, whether the pattern was woven or printed, and the shape and size of the whole shawl. The accompanying example of the paisley-pattern shawl shows how a single design motif has defined the name of this particular shawl. Although the shawl material could be silk, wool or cotton, it is the presence of this pattern motif that results in the name. Some shawl definitions have been established by long-standing traditional construction methods. However, these methods can overlap. For example, a traditional rectangular shawl can be knitted by using several different methods. It may also include specific stitch patterns typical of a distinct region that are designed specifically to fit within that particular rectangle construction.

When considering why one would ever bother with a knitted wrap, as opposed to one of an alternative material or fibre, Tessa Lorant tells us:

Well of course it doesn’t have to be knitted; but for keen knitters making some sort of wrap is a delight; even the beginner can learn to make a ‘patterned’ rectangular wrap without the need to shape or worry about the tension. And an advanced knitter can show intricate pattern knitting off to perfection. Not only that, wraps can be made in thick yarn or in thin, and in knobbly, brushed or other fancy yarn as well as in the ordinary knitting fingerings. They can also be made in different fibres, in many colours, in toning colours, or in a single colour only. The wrap can be embellished with lace edgings, with frills or with flounces, or it can simply be fringed to finish it off.

Knitting a shawl can therefore be considered as a way of experimenting. This can be with a new yarn, an interesting technique or a beautiful stitch pattern. There blanket cape christening cloud comforter crossover Estonian Faroese fichu hap muffler neckerchief neck handkerchief nightingale pashmina pelerine poncho rebozo ruana ruffle scarf shawl Shetland stole tippet veil wedding wrap wrapper are a very large number of beautiful and interesting shawl patterns already designed and ready to knit. However, this book is all about creating shawl designs that are truly personal to the knitter or the intended recipient. Bringing new inspiration into shawl design may call for a new set of names and descriptions that reflect the very personal inspiration of the designer and wearer. Although choosing to design your own shawl can at first seem daunting, creating a new and original design is extremely rewarding and enjoyable.

List of shawl names

blanketpelerinecapeponchochristeningrebozocloudruanacomforterrufflecrossoverscarfEstonianshawlFaroeseShetlandfichustolehaptippetmufflerveilneckerchiefweddingneck handkerchiefwrapnightingalewrapperpashminaDesign Inspiration

Thinking about the particular inspiration and starting points of a shawl in detail can give structure to a project and really help to communicate the design to other knitters. These ideas can be used to spark other ideas for new stitch patterns, shawl shapes or colour schemes. Most importantly, it can help with decision-making during the designing of the whole shawl. The chosen inspiration can feed into some parts only or the whole of the design, affecting the shape, edgings and pattern placements. It is the combination of all of these inspirations together that results in original shawl designs.

Las Setas, Seville, Spain.

Detail from the Las Setas Shawl.

Look out for these inspirational elements wherever you go. Carry a notebook, and make sketches and take photos of anything that catches your eye. Tiles, paving stones, railings, flowers, clouds and buildings are just a few examples that can be found in the world around us. Tiny details can be scaled up through design development to become bold patterns. Complex tree branches can be simplified into smooth cable curves. Consider colour, shape and perhaps location. The key point is to feel inspired and think about what has inspired you. For example, the structure, shape and colour of Las Setas in Seville, Spain, inspired the shawl design of the same name. The description and explanation of designing this shawl can be found in Part 3 of this book, along with the full knitting pattern.

Las Setas Shawl.

Taking inspiration from the world around us can also generate new and exciting ideas. Researching a building or a plant in great detail can reveal interesting facts that can be reflected in the design. By choosing subjects that have an interesting background, a design can become a very personal expression for the knitter. For example, knowing that a plant produces berries in autumn can lead to a series of stitch patterns that include leaf motifs, flower inspiration and berry bobbles. These individual stitch patterns will all relate to each other and are unified through the research undertaken on a single subject.

Another excellent starting point is an exploration of a particular knitting technique such as cable knitting or a style relating to a tradition or geographical region. Research at a museum or heritage collection can provide an excellent framework in which to explore shawl styles, shapes and patterns. Using historical research to inspire a shawl design has the added benefit of highlighting techniques that have been in use for a considerable period of time. These techniques can be the building blocks of new designs. The KCG Collection has many beautiful shawls, and a selection of these are considered in detail in this book.

The design can be further developed by using a different yarn weight or fibre, or an additional colour. A stitch pattern can appear completely different when worked in a different yarn or fibre. Small changes can have drastic effects on scale, colour balance and pattern. The effect of different yarn weights and fibres are highlighted throughout this book. Knitted swatches demonstrate the differences that can be achieved, especially in the design-development stages.

Having set the scene for shawl design, the next step is to place shawls in a wider context: Chapter 1 explores shawls through tradition, innovation and inspiration.

Part 1

SHAWL DESIGN IN CONTEXT

CHAPTER 1

TRADITION, INNOVATION AND INSPIRATION

There is a very large number of well-recognized and much-loved traditions in shawl design. Each tradition has its own signature style and construction conventions, in many cases defined by the shape of the shawl and the placement of pattern. However, these distinctive patterns have been amended and adapted over time, to suit the different requirements of different designers, knitters and wearers. Examining the skills and knowledge of knitters over time and in different geographical areas helps us to understand the techniques that were used to create their shawls. Additionally, we can attempt to infer what actually inspired the original shawls and stitch patterns. In many cases, the answer and impetus are a combination of outstanding technical skill, economic necessity and a keen eye for pattern. Tradition, innovation and inspiration are therefore strongly linked and exert equal influence over historical and contemporary shawl design.

Pattern detail from mirror-imaged rectangular shawl, KCG Collection (1998.071.0010).

In her excellent 2008 book Knitted Lace of Estonia, Nancy Bush likens the knitting of a shawl to handwriting, demonstrating the individuality of style within established tradition:

Although I originally thought that there was a single right way to knit these shawls, I have learned that there are nearly as many ways as there are knitters. Just like handwriting, each knitter has her own way of knitting certain parts of a shawl, and I found that it is quite acceptable to make a change because it worked better for me.

Commenting on the recording of the shawl patterns, Nancy Bush also highlights a way of passing on information that is common to many traditions:

The Estonians had no written instructions for their patterns – the techniques and designs were handed down from one generation to the next. Stitch patterns were preserved on long knitted samplers or as individual sample pieces.

The passing on of information in this way allows small changes and customization to be incorporated into the designs, all within the boundaries of the tradition.

Seventy-five individual stitch patterns for Haapsalu shawls were compiled for the beautiful book Knitted Shawls of Helga Ruutel (2013). These designs represent only a small selection of approximately 200 charted designs created by Helga Ruutel over several decades. Instantly recognizable as traditional Haapsalu shawls, Helga placed her own individuality into Haapsalu shawl patterns. Her comments reveal that she was very much aware that she was breaking with tradition:

I changed the yarn overs and decreases of historical shawl patterns. Many thanks to master knitters who did not utter any bad words to a young troublemaker. My wings were not clipped and so, until now, patterns from here and there have been scattered upon my shawls.

These examples clearly demonstrate the importance of the individual in creating traditional patterns. Over time, traditional shawls have been adapted and altered by generations of knitters. Established patterns therefore contain design elements from all of the previous generations of knitters and designers, each bringing their own inspirations and ideas to the traditional practice.

The first section in this chapter explores tradition and innovation in shawl design through selected items held in museums and collections in the United Kingdom (UK). These resources can be accessed either in person or through digital archives. It is important to recognize and to reference techniques and ideas already in existence. This understanding provides the context for new designs. A case study of items from the KCG Collection helps to show the importance of this type of research.

This chapter concludes by placing shawl design in the wider context of fashion. This shows how accessories have been influenced by fashion trends over the years, from simple shapes of a length of cloth wrapped around the wearer for warmth, to elaborate paisley-pattern shawls used to show the wealth and status of the owner. Innovations in technology now allow customization of machine-knitted accessories. However, this book proposes that the ultimate for a customized design is a hand-knitted shawl with a shape, edgings and stitch patterns inspired by sources with personal importance to the designer and wearer.

Museums, Exhibitions and Collections

Researching shawls in museums and archives can really help to achieve a good understanding of traditional styles. This can be undertaken through the handling of items, through the reading of books, leaflets and patterns, and through the viewing of digital archives. There are many excellent resources available for online research and in-person visits. In this section, several examples are considered to demonstrate the breadth of information available in the UK.

The Knitting Reference Library at the University of Southampton Winchester Campus provides a wealth of information for knitters and researchers. Browsing the shelves reveals most of the major knitting styles from over the last hundred years. The online collection of Victorian knitting books takes the reader further back in time and allows the exploration of knitting, crochet and netting during the Victorian era. All of this taken together provides a helpful overview and starting point before exploring new shawl shapes and designs. For example, writing in the second volume of the Lady’s Assistant in Knitting, Netting, and Crochet Work, Mrs Jane Gaugain provides a pattern for a fichu. As well as a detailed set of written instructions for this small shawl, Mrs Gaugain provides her readers with a schematic diagram. The diagram shows the outline of a triangular shawl with the addition of a curved notch for the neck. Blocking instructions highlight this feature and show that, although the basic shape of the fichu is a triangle, Mrs Gaugain encourages knitters to adapt the shape for a custom fit.

Entire museum exhibitions have been devoted to particular symbolic shawl styles. The Fashion and Textile Museum (FTM) in London was host to a wonderful exploration of the rebozo shawl. In the 2014 exhibition ‘Made in Mexico: The Rebozo in Art, Culture and Fashion’, the FTM highlighted a shawl style made popular by the artist Frida Kahlo. Placing the shawl in a wider context, the exhibition considered how the rebozo has promoted Mexico throughout the world. This shawl not only is considered a traditional garment but also captures the essence of the country of origin and became known as a cultural emblem. As a source of inspiration, this exhibition provided a wealth of colour, texture and technique. Visitors were able to discover a wide variety of historical and contemporary examples of rebozo-shawl design.

Studying specific examples of shawls in museums, exhibitions and collections also reveals evidence of knitters customizing traditional designs. This can be an unexpected pattern placed within the shawl shape or an interesting new construction method. The following examples were encountered on a research visit to the KCG Collection that provided the opportunity to view knitted shawls and knitting publications and, most importantly, to talk to the knowledgeable archivists.

The Knitting and Crochet Guild Collection

A large number of fascinating shawl examples can be found in the KCG Collection. The Collection is located in Britannia Mills in Slaithwaite, UK, and is available to view by appointment. Many items are now digitized and can be viewed through the Guild’s website, https://kcguild.org.uk.

The shawls in the KCG Collection provide an excellent insight into of some of the main styles of what are sometimes called traditional shawls. Many of the items in the Collection are donations from anonymous knitters or their families. The Guild accepts these donations as they are a record of items knitted in the home by knitters of many different skill levels. This section examines a selection of these shawls as examples to demonstrate how exploring the detailed construction of a shawl can inspire ideas for new shawl designs.

There are many ways to explore knitted items in a collection. These include handling the item carefully, usually wearing gloves, to examine joins, seams and edgings; photographing interesting details for a record of the visit; and sketching and drawing details. In particular, the technique of close-looking can be very helpful in this type of exploration. Art and dress historian Dr Ingrid E. Mida promotes drawing as a research tool in her recent book, Reading Fashion in Art (2020). In her lectures, most recently as part of a series of talks hosted by the Sartorial Society, she encourages this method of examining items. The close-looking approach is where the researcher uses drawing to visually explore the subject. It can lead to insights that would otherwise be missed by only taking a photograph:

Drawing slows down and extends looking and, in the process of translating marks on to the page, the brain is able to discern additional information not otherwise seen in a single glance.

Details from shawls in the KCG Collection are described in this section, with reference to my own drawings and photographs of the items. Exploring these different shawl construction methods reveals many different ways to knit a shawl, especially focusing on examples of knitters adapting methods for their own particular designs.

Nineteenth-century rectangular shawl

One of the most straightforward ways to knit a shawl is to make a rectangle by casting on a number of stitches, knitting until the desired length is reached and then casting off the stitches. The effect of pattern placement and shawl construction within rectangles is beautifully illustrated through examples in the Collection.

An example of a hand-knitted nineteenth-century stole is this rectangular shawl knitted in a delicate lightweight cream wool yarn. The garter-stitch edgings have been knitted at the same time as the central pattern. Several rows of garter stitch have been worked before the main stitch pattern starts. Garterstitch side borders, a few stitches wide, are worked at the beginning and end of each row. This simple border contrasts beautifully with the interlocking-leaf design knitted in the central panel.

Detail from nineteenth-century rectangular shawl, KCG Collection (2020.000.0030).

Sketch of nineteenthcentury rectangular shawl from the KCG Collection.

Pattern detail from nineteenth-century rectangular shawl, KCG Collection (2020.000.0030).

Sketch of detail from nineteenth-century rectangular shawl from the KCG Collection.

An overall sketch of the stole and the stitch patterns helps to provide the starting point for a close exploration of the design. Drawing the delicate detail of the pattern shows how a long series of pattern repeats can be used as an elegant design feature. In this case, the same leaf motifs are repeated over the width and length of the shawl, creating unity in the design. Each leaf is formed with a series of eyelets. The curving lines of the motif contrast with long lines of eyelets running the full length of the rectangular shawl.

This shawl is an excellent example of the principles of creating a rectangular shawl. There is a border pattern that begins at the cast-on edge and runs up both sides of the shawl. The border appears to be knitted at the same time as the pattern. The knitter has calculated the number of stitches needed for the pattern repeats, added those needed for the two side borders, and then cast on this number of stitches. The choice of yarn has an effect on the pattern: knitted in a pure-wool yarn, the stitch-pattern structure is clearly visible.

Mirror-imaged rectangular shawl

Another rectangular-shawl example from the Collection shows several traditional construction techniques, including an intriguing mirror-imaged stitch pattern. This fine shawl has been knitted in Jamieson and Smith 1-ply (singles) cobweb-weight yarn. Close-looking reveals that this shawl is knitted from the centre outwards, with a border added after the rectangles were completed.

Centre-section detail from mirror-imaged rectangular shawl, KCG Collection (1998.071.0010).

A provisional cast-on is the starting point for the first rectangle. After this rectangle is completed, the stitches from the provisional cast-on are unravelled. The revealed stitches are most likely picked up and used as the starting point for the second rectangle. Alternatively, a second matching rectangle is knitted with a provisional cast-on and the two rectangles are later grafted together. Both of these techniques ensure a mirror-imaged pattern. The two sides are nearly identical. The only difference is the starting point for the second rectangle. The whole central panel is worked as part of one of the rectangles and the join is on one side of this panel. The stitch pattern can be viewed either way around. However, close inspection reveals the direction of the stitches and the location of the join.

Sketch of centre section of mirror-imaged rectangular shawl from the KCG Collection.

To complete this rectangular shawl, an outer border has been added around the whole shawl shape. Stitches were cast on for the border, and it was most likely attached as it was worked. To do this, the last stitch of every right-side row was knitted together with a loop from the edge of the shawl. Again, to create a seamless join, the border cast-on can be a provisional version. When the border is completed, the final stitches are grafted together with the cast-on stitches themselves or, if a provisional cast-on has been used, with the revealed live stitches at the cast-on end of the border.

Close-looking through sketching and drawing helps to reveal many details that are not immediately apparent. The sketches are made on different scales, from an overall plan of pattern placement to detail of the eyelets. Through these sketches, the direction of the stitch pattern becomes clear, and the joins between the sections of this fine shawl are a joy to observe. This stunning shawl is clearly the work of a master knitter.

Sketch of detail from mirror-imaged rectangular shawl from the KCG Collection.

The techniques used throughout this spectacular shawl demonstrate that shawl shapes can be made up of many components. From the mirror-imaged pattern to the order of construction, this shawl shows that there are many different ways to construct rectangle shapes and to place stitch patterns within these rectangles. The addition of the border after the centre was completed in the second example contrasts with the first shawl example, where the border was knitted at the same time as the central pattern. Decisions on pattern placement and construction order are key to the appearance of the final shawl design.

Construction methods can be explored further in books. An excellent resource is Heirloom Knitting by Sharon Miller, published in 2002, a copy of which is held in the KCG Publications Collection. In her book, Sharon Miller provides beautiful illustrations of many Shetland-shawl construction methods. She includes ways to construct rectangles, squares, triangles and circles. The steps involved show how knitters use a combination of inherited traditional techniques combined with their own creativity to design shawls that are passed down through families over the years. The merging of individuality with tradition has resulted in truly original ideas.

Centre-section detail from square shawl, KCG Collection (2002.065.0009).

Square shawl

A square shawl can be constructed in a similar way to a rectangle, with stitches being cast on for the full width, rows being worked until the sides are the same length as that of the cast-on edge and then casting off to complete the shape. This fine-gauge square shawl in the Collection demonstrates a different construction technique; it is worked from the centre of the shawl outwards. There are four lines of increases, and the initial centre increase pattern has been used as a decorative feature, creating a beautiful flower motif.

Sketch of centre section of square shawl from the KCG Collection.

This central pattern has rotational symmetry, with each of the four flower-petal panels being worked in the same way. The pattern contrasts beautifully with the outer-panel patterns. The long lines of eyelets that create the square shape begin within this motif and extend to the four corners.

Circular shawl

It can be seen from the previous examples that there are many different ways to knit shawl shapes. The KCG Collection features several variations on circular shawls, including one that demonstrates a wonderful swirl effect. Similar to the previous square-shawl example, this circular shawl is worked from the centre outwards. This knitter has also started the shawl with a distinctive decorative-centre increase section. In this case, the centre is worked in stocking stitch, contrasting with the main-panel pattern. To create a circular shape, there are seven increase lines radiating outwards for the centre panel. The decorative increase lines are formed of eyelets, and they spiral outwards towards the outer border. In contrast to the straight lines of increase in the square-shawl example, these increase lines appear to move. This is achieved by working the increase one stitch after the position of the increase of the previous increase round.

Detail of circular shawl, KCG Collection (2012.000.0054).

Sketch of circular shawl from the KCG Collection.

The use of a variegated yarn, with multiple shades, in combination with a single-shade cream yarn, creates a lovely marl effect within the stitch pattern. The stripes of the colours are readily apparent within the stocking-stitch centre. These subtle stripes of colour become blurred within the main-shawl panels.

The shawl is completed with two border patterns; one is knitted as part of the main-shawl body and a second one is added around the entire outer circumference. The first border is worked in an old-shale or chevron pattern, in the round. Once this first border pattern is complete, a small number of stitches are cast on and a striped garter-stitch border is worked lengthwise. One stitch at the end of every right-side row is knitted together with a live stitch from the outer edge of the shawl. This border has been worked in stripes, using the same yarn shades as used for the main-shawl body. It creates a beautiful contrast to the main-shawl stitch patterns, with the stripes at right angles to the main-shawl colour stripes.

Edging detail from circular shawl, KCG Collection (2012.000.0054).

Sketch of edging from circular shawl from the KCG Collection.

The interaction between the edging and the main shawl is shown in the sketch of the spiral-shawl border. A lovely scalloped edge has been formed by working the knitted-on edging after the chevron pattern. The increases and decreases of the chevrons cause the garter-stitch edge to undulate.

These fascinating examples from the KCG Collection demonstrate just a few of the myriad techniques that can be used to create a variety of different shawl shapes. They also demonstrate that knitters have always adapted and refined their work to suit the project and their own strengths. An appreciation of the shawls and the people who created them adds context to new designs.

Engraving from Journal des Dames et des Modes, Costume Parisien, 25 Octobre 1809, Rijksmuseum Collection (http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.487455).

Fashion Trends and Shawl Design

Fashion trends have a profound effect on accessories of all kinds, and shawls are no exception. Looking at historical and contemporary fashion trends can put designs into context and stimulate new ideas for shawls. For example, as dress silhouettes evolved to include wide skirts in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, shawl sizes increased in scale to be displayed over this framework. Shawls, such as the paisley shawl, have in turn influenced garments. In this case, after the fashion for this style of shawl began to wane, paisley shawls were remade as garments, with the distinctive patterning appearing on clothing of all kinds. The dialogue between accessories and fashion is ongoing. Importantly, accessories are often the more accessible and affordable part of high-fashion catwalk collections.

Shawl, anonymous, c.1800–1825, Rijksmuseum Collection (http:// hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.28406).

Illustration from La Mode, 25 September 1835, Pl.472: Chapeau de pail de rim, Georges Jaque Gatine, after Louis Marie Lanté, 1835 (http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.488615).

Online museum collections, such as those of the Rijksmuseum, the Netherlands, can provide an excellent visual timeline of changing styles through art and design illustrations. Searching and browsing beautiful images provides an overview of shawl shapes and shawl patterns and reveals how they have changed over time. Beautiful illustrations from the Mode de Paris