28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

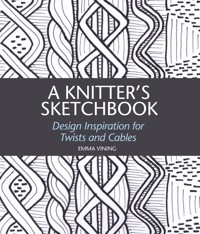

Inspiration for twist and cable designs can be seen everywhere in the natural world and the urban environment, from the cracks in the pavement to building walls, posts and pillars. In A Knitter's Sketchbook: Design Inspiration for Twists and Cables, creative designer Emma Vining shares her experience of capturing pattern ideas in many diverse locations and settings, offering a design-led approach to creating unique knitting stitch patterns. This inspirational book takes a new look at hand knitting techniques that uses twisted stitches and cables. It can be used in many different ways: as a stitch library, a collection of knitting patterns or as a starting point to inspire designers for a personalized knitter's sketchbook. This beautifully illustrated book explores: the history of knitted twists and cables; demonstrates how using different yarns affect stitch patterns; describes twist and cable techniques and terminology; presents a wide-ranging stitch library with ideas to inspire further designs; illustrates the techniques with ten creative accessory patterns. This book illustrates these techniques with ten creative accessory patterns in the form of 189 colour photographs and 141 line artworks.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 350

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

A KNITTER’SSKETCHBOOK

Design Inspiration forTwists and Cables

EMMA VINING

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2019 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2019

© Emma Vining 2019

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 538 1

Frontispiece: Tulip-bud scarf (seeChapter 13).

CONTENTS

Introduction: What is a Knitter’s Sketchbook?

Part 1: Context

1 Historical Context

2 Terminology and Techniques

3 Yarn and Tools

Part 2: Line and Shape

4 Straight Lines

5 Curved Lines

6 Straight-Sided Shapes: Diamonds

7 Straight-Sided Shapes: Hexagons

8 Curved Shapes: Circles And Ovals

Part 3: Enhanced Twists and Cables

9 Combined Curves

10 Openwork

11 Texture

12 Short Rows

13 Layers

Glossary of Terms

Abbreviations

Bibliography

Further Information

Acknowledgements

Index

INTRODUCTION:WHAT IS A KNITTER’S SKETCHBOOK?

The title of this book reflects a design-led approach to creating knitting stitch patterns. This method of design combines my love of knitting with an awareness of pattern inspiration at different scales and from diverse locations. Inspiration for twist and cable designs can be seen everywhere in the natural world and in the urban environment, from cracks in pavement to patterns in the walls of buildings and from posts and pillars. Sometimes just looking down at the ground can provide the best source material, from an elegant mosaic pattern in a town plaza to shadows cast by the sun shining on railings on a bridge.

Fig. 1

Part 1: Context

CHAPTER 1

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Before beginning to explore new stitch patterns, a look back in time is essential. By gaining an understanding of the historical uses of twists and cables in knitting, we can appreciate the enormous range of techniques that have been in use over several hundred years.

Fig. 5 1891 knitted stitch sampler. (KCG Collection; photo: Angharad Thomas)

Traditional knitting styles have used twist and cable patterns in many different ways, such as an embossed, raised line on a plain background or as a design feature within lace knitting. In gansey knitting, for example, cables are just one element of these garments containing multiple stitch combinations. In this style of knitting, the link between the twists and cables and the many ropes found on a fishing boat is clear. In Aran knitting, the individual twist and cable stitch patterns themselves have taken on meaning, with many complex combinations having their own specific names.

The review of historical examples in this chapter sets the context for the new designs in this book. So many beautiful cable patterns have been created already, and the aim of this book is to add to this body of design, not reproduce it. As well as referencing twist and cable designs that have been extensively used and are much loved for their specific stitch combinations, this chapter looks back to the time before Aran and gansey patterns became established. By considering early cable designs, the techniques and applications common to all twist and cable designs become apparent.

Although it would be exciting to find the very first example of a knitted twist or cable, this is not possible, for several reasons. Historical knitting research is restricted by the lack of actual examples that exist. Conservation of knitted items is a relatively recent development. Previously, knitted items of clothing were seen as functional objects for everyday wear. Many of the knitted garments and accessories would have been unravelled and reknitted as the wearer grew out of them or simply wore them out. Additionally, as an organic textile, knitted items made of wool decay over time, and, in many cases, only fragments of the original fabric remain. Examples of exceptional knitting do exist in museum collections; these include brocade silk jackets knitted in Italy and silk stockings knitted for wealthy landowners and royalty. Although these examples show texture, colourwork and surface decoration, there is limited evidence of the movement of stitches that we would call a twist or a cable.

Knitted samplers

Some of the earliest evidence of twist and cable knitting from the British Isles can be found within knitted samplers. These samplers were typically knitted by students either learning from a teacher or knitting at home. The samplers exist in several different forms, with some containing individual swatches stitched into a fabric book and others consisting of a long, narrow strip of multiple stitch patterns. Several beautiful examples are held in textile collections, such as those of the Victoria and Albert (V&A) Museum Collection.

Fig. 6 Sketch of detail of the 1891 knitted stitch sampler.

Fig. 7 Sketch of detail of the 1891 knitted stitch sampler.

Many of these samplers do not have a specific date of making. Instead, a wide time period over which they may have been made is referenced in the catalogue descriptions, for example, 1750 to 1850. Although catalogue entries often describe the sampler stitch patterns as being of lace or openwork knitting, many of the samplers also contain twisted stitches and cables. The stitch gauge of the knitted samplers is very fine, making the cables prominent against the background stitch pattern. Cable and twist stitch patterns found on many of the long-strip samplers include textured lattice arrangements, such as the example represented in the sketch shown in Figure 6. Another example is the long lines of twisted stitches separated by contrasting stocking stitch bands, represented in the sketch shown in Figure 7.

Fig. 8 Sketch of twisted stitches and eyelets from a section of the KCG 1891 knitted stitch sampler.

Fig. 9 Sketch of cables and lace lattice from a section of the KCG 1891 knitted stitch sampler.

Fig. 10 Sketch of cablecrossing detail from a section of the KCG 1891 knitted stitch sampler.

These types of stitch arrangements are also found within a late-nineteenth-century sampler held in the extensive collection of the Knitting & Crochet Guild (KCG) of Great Britain. This sampler, shown in Figure 5, is made up of sixty-three different knitting stitch patterns. One of the sections includes the initials of the maker and the year of the knitting: ‘A.F. 1891’. Fine, white, cotton yarn has been used in this project, and the gauge has been measured at seventy-eight stitches by one hundred rows over ten centimetres (four inches). Working at this level of detail results in the beautiful stitch definition of the patterns. As shown in Figure 5, a fifty-pence piece has been placed next to the sampler, to reveal the scale of the stitch patterns. The majority of the stitch patterns in this sampler are of lace. However, as with other sampler examples, there are several knitted twist and cable sections in amongst the knitted lace panels. These sections are illustrated in the sketches shown in Figures 8, 9 and 10.

The sketch shown in Figure 8 represents a twisted stitch and eyelet design from the sampler. The twisted stitches move from side to side within a narrow panel. Each narrow panel is separated by a long line of eyelets, with the eyelets having been worked on every row.

The sketch shown in Figure 9 represents a cabled lattice-stitch pattern in the same sampler. The lattice includes eyelets on the lower part of each diamond shape and an eyelet pattern in the centre of each diamond. The cable stitch movements at the intersections of the diamonds are all worked in the same way. This detail is shown in Figure 10.

Knitting publications

The knitting of samplers can be related to an explosion in publications about knitting, netting and crochet that occurred in Victorian times. These publications marked the change of knitting from a functional skill, for the production of everyday garments in continuous use, to a leisure activity for Victorian ladies. As a leisure activity, many delicate and detailed accessories were created, and new ideas and patterns were constantly sought by knitters. Before these publications became widely available, knitting was a skill that was mainly taught by word of mouth and by example. Patterns were passed on as children learned to knit by watching a family member or a teacher. Richard Rutt, in the historical glossary (p.226) of his 1987 book A History of Hand Knitting, lists the term ‘cable’ as first appearing in print in a knitting context in 1844. He points out that, although there are very few published references to knitting before 1837, terms used around that time will most probably already have been in use for a considerable period of time, even centuries.

Some of the earliest knitting publications are held in the National Art Library at the V&A Museum in London. A wide selection of Victorian knitting books, by several of the leading knitting figures of the day, are available for study. While references to cable patterns in any form are very limited, there are some interesting technique observations to be found in these delightful books.

Miss Lambert’s needlework book of 1844 is one example that contains a cable pattern that is actually titled ‘Cable Knitting’ (p.54). Miss Lambert’s cables are six-stitch cables worked with a left slant. The pattern instructions do not allow for any stitches to be worked between the cables. The cables are worked after seven rows of ‘pearl’ knitting and plain knitting. The pattern uses a third needle on which to slip the first three stitches. This stitch pattern sits amongst a variety of patterns for a great number of projects and stitch patterns. However, it is the only cable pattern in the entire book. It appears to be noted purely as an additional stitch pattern that is available for the knitter to use, as it does not form part of an accessory or garment pattern.

The cable patterns in these publications all specify a third needle or wire to work the cable. Each pattern gives directions as to where to place the stitches and the third needle, at either the front or the back of the work. Some patterns, such as the ‘Cable Insertion’ in Mdlle Rigolette de la Hamelin’s The Royal Magazine of Knitting, Netting, Crochet and Fancy Needlework, No. 4, instruct the knitter to work the cable over two rows. The spare stitches remain on the third needle until the position of the cable is reached when knitting the second row.

Fig. 11 Sketch of twists and cables similar to those of old Scotch stitch.

‘Beautiful Old Scotch Stitch’ is referred to in the third edition of The Lady’s Assistant in Knitting, Netting and Crochet Work, published in 1846, by Mrs Jane Gaugain. This stitch pattern is described in detail in the book and is used in knitting patterns designed by Mrs Gaugain. Old Scotch stitch consists of a combined twisted stitch, cable and lace pattern. There are several different types of twist and cable stitch movements, including two cables of different numbers of stitches. Figure 11 shows a sketch of combined twists and cables that are similar to those of old Scotch stitch, with eyelets forming an integral part of the pattern.

Most importantly, in an accompanying note to a pattern ‘For Baby’s Caps, Cuff, &c. &c.’, Mrs Gaugain informs her readers of the stitch pattern’s origin: ‘This stitch is copied from a knit cap which was worked in Scotland more than 140 years since; I shall afterwards, in this Volume, produce it for a bed coverlet, &c. &c.’ (p.45).

Mrs Gaugain’s comment implies that cables had been in common use from the beginning of the eighteenth century. Although not conclusive evidence, this shows that there was already an assumption about the extensive use of cable-style knitting in the nineteenth century.

Bedcovers and counterpanes

As well as the many fine and detailed accessories created by Victorian knitters, other popular knitted items of the time were bedspreads, carriage blankets and counterpanes. The descriptions of knitted counterpanes in Mary Walker Phillips’s 2013 book Knitting Counterpanes reveal that a cable was often used as a way of making a long, straight, vertical, raised line. Construction of the counterpanes was usually in separate pieces that were sewn together in the desired configuration after the knitting was complete. The cabled sections were often knitted in multiple long strips containing a mix of stitches.

In these patterns, the long lines of twisted columns are being used as part of the overall design of the knitted item. It is important to note the scale of the knitted item. A bedcover, counterpane or carriage blanket is a very large item that can have multiple decorative details on the same piece of work. Stockings and hats, the mainstay of earlier domestic knitting, have a smaller area available for decoration. Much of the detail would have been added afterwards through embroidery, and possibly with a contrasting shade of thread or yarn, rather than as a knitted-in twist or cable feature.

Fig. 12 Detail of knitted bedspread by Hannah Smith, 1837. (KCG Collection; photo: Angharad Thomas)

Fig. 13 Sketch of stitch patterns on 1837 knitted bedspread.

The KCG Collection includes the knitted bedspread that is shown in Figure 12. This item is quite unusual, as it can be dated and attributed to a specific maker. The name of the knitter and the date of the knitting have been recorded in purl stitches on a stocking stitch background within the bedspread itself. The panel reads ‘Hannah Smith 1837’. The bedspread uses the long-strip technique and includes multiple cables, as well as sections of contrasting textural knitting. There is even a beautifully darned area, showing that the bedspread was well used and constantly maintained. A selection of intersecting stitch patterns are highlighted in the sketch shown in Figure 13. A textural basket-weave pattern contrasts with the bold cables on a garter-stitch background and with the neighbouring honeycomb pattern.

A published example of this long-strip technique, also including the old-Scotch-stitch pattern referred to previously, can be found in the 1846 publication of The Lady’s Assistant in Knitting, Netting and Crochet Work by Mrs Jane Gaugain, in a pattern for a ‘Very Handsome Knit Bed-Cover’, which is ‘Composed of alternate stripes of the Old Scotch Stitch and a stripe of basketwork stitch. When knit to the length required, and as many stripes as are wished for the width of the counterpane, sew or knit them together’ (p.122).

The instruction for the basketwork stitch includes a precise description of the knitting technique required, as Mrs Gaugain had written a detailed footnote (p.125) to help the knitter:

Here lies my difficulty of description. – Take the right hand pin, and insert the point of it through to the front, between the first and second stitch on the left hand pin; work the second stitch in the common way, keep it on the left hand pin; you now have one stitch on the right hand pin; now work the first stitch from off the left hand pin, which is done in the common way. Now lift them both off the left hand pin. I gave this to a girl of 14 years of age to try, and she accomplished it, although I had my doubts concerning it. Both stitches in this bed-cover will not be found in the knowledge of many persons.

The description shows that the basketwork pattern comprises a two-stitch twisted stitch. The pattern instructions use the description for both right-side and wrong-side rows, revealing that the twists are worked as pearl stitches as well as plain. This bedcover pattern therefore contains both cables and twisted stitches, worked on both the right side and the wrong side of the knitting. It appears from the description that, despite her claim mentioned earlier, that the old-Scotch-stitch pattern has been in existence for the previous 140 years, Mrs Gaugain feels that the techniques required to achieve the stitch patterns are not well known. Clearly concerned that her readers would not be able to achieve either stitch pattern, Mrs Gaugain gives her knitters an alternative stitch pattern: ‘Should the basket-stitch be found too difficult for comprehension, common garter stitch stripes may be substituted’ (p.126).

Gansey and Aran knitting

The word ‘traditional’ implies a set knitting procedure that has been used again and again over many years and is instantly recognizable. Gansey and Aran knitting certainly fit this description. However recognizable these stitch patterns are, there is much evidence to show that they have evolved and changed over time, by either the deliberate or the accidental sharing of ideas.

The many ropes used on a fishing boat were an obvious inspiration source for early cable knitters. This link between ropes and knitted twists and cables is clear when reading the dictionary definitions of the words. The 1976 Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English noun definition of ‘twist’ refers to a ‘thread, rope, etc., made by winding two or more strands, etc., about one another’, and the verb definition of ‘twist’ means ‘the act of twisting, condition of being twisted’ (p.1256). For ‘cable’, the noun is defined as a ‘strong, thick rope of hemp or wire’, and the definition of ‘cable stitch’ is a ‘knitted pattern looking like twisted rope’ (p.137).

As representations of different sizes of ropes, cable stitch patterns on a gansey sweater were worked on different scales, with different numbers of stitches and numbers of rows between twists. From fine, two-stitch lines to wide, eightstitch braids, ropes provided knitters with a great inspiration source. Combinations of knitting stitches have been attributed to specific geographical areas and, in some cases, specific knitters. However, similar patterns can be found in very different geographical areas throughout the British Isles. The emergence of these related patterns in different parts of the country can be explained by the very nature of the fishing industry that inspired the patterns in the first place. As the fishing boats arrived in different ports, the patterning of a gansey from a far-away port was brought up close to a knitter who may in turn have been inspired to develop their own version. New stitch combinations emerged, but the similarity remained; hence, the evidence of the occurrence similar patterns at distant ports is accounted for.

Aran knitting emerged as a distinct style in the twentieth century. In Gladys Thompson’s 1979 book, Patterns for Guernseys, Jerseys & Arans, the author makes some interesting comparisons between these different but closely related types of knitting. She notes that, while ganseys have always been knitted in the round with a very particular construction method, Aran sweaters were often knitted in pieces and then seamed. However, Thompson proposes that it is the use of travelling stitches across the surface of the knitting, along with cables in the design, that makes Aran patterns distinct from those of ganseys.

Later developments in Aran knitting in the early twentieth century have also resulted in many stitch combinations being named after the pattern that they resemble or the inspiration source that they came from. These clues to the knitters’ thinking are important to recognize. The horseshoe cable, for example, actually resembles a horseshoe. The many versions of wave patterns are much more of an interpretation of the sea. Although the patterns all refer to waves, they are constructed in several different ways. A similar approach is taken throughout this book. The inspirational source material is the key component of the designs, and the stitch combinations chosen represent the essence of the pattern, shape or form from the source and the response to it. The naming of a pattern is helpful but does not always reveal the specific design behind it.

In her 1983 book, The Complete Book of Traditional Knitting, Rae Compton suggests that a great deal of experimentation was present in early Aran-style knitting before the designs became more commercialized. Compton suggests that early Aran garments were usually created for a specific wearer, with the knitter having complete control over the design. The pattern would often be different between the front and back of the garment, but the designs would always be linked. The set-in sleeves of these early Aran sweaters also functioned as the link between the front and back patterns. Knitters would add design elements while they were knitting and would experiment with different stitch combinations in different sweaters.

As the Aran industry became more commercialized, there was a need to standardize some of the stitch patterns. This was in part driven by the requirement to make multiple sizes of a similar design. The stitch-pattern panels were often bordered by a more simple design that could be widened or narrowed as needed. Raglan sleeves were introduced. Another change at this time was the need to write patterns down in order to share the instructions. Previously, patterns had been handed down by word of mouth, with no need for the instructions to be written line by line.

Alice Starmore, in her book Aran Knitting, defines an Aran sweater (p.46) as follows:

… a hand knitted garment of flat construction, composed of vertical panels of cabled geometric patterns and textured stitches. On each piece of the sweater there is a central panel flanked by symmetrically arranged side panels. The use of heavy undyed cream wool is a classic – though not essential – component of the style.

This definition is an excellent way to consider the underlying structure of many of the historical Aran sweaters in museum collections. It also provides a framework with which to view the developments that occur within Aran-style knitting as consumer demand and fashion trends called for an expanding variety of styles and construction methods.

Barbara Smith, publications curator for the KCG, considers the development of these new twist and cable stitch patterns as an evolution of Aran style. Rather than there being a single definitive set of stitch patterns, or a definitive method of Aran garment construction, the many different cables, twists, bobbles and lace stitch patterns have continuously evolved and changed, to reflect the fashion trends of their times.

Fig. 14 Reconstructed 1936 Aran sweater. (KCG Collection; photo: Norman Taylor)

Three garments held in the KCG Collection are examples of some of the changes that occurred within Aran-style knitting during the twentieth century. The first example, shown in Figure 14, is a reconstruction of a sweater that was knitted in Dublin, Ireland, in the early twentieth century.

The original sweater was one of the first recorded examples of complex Aran patterning and was purchased in Dublin in 1936 by the historian Heinz Kiewe. The stitch patterns on this original sweater were recorded and illustrated by author Mary Thomas in her classic 1943 book, Mary Thomas’s Book of Knitting Patterns.

Fig. 15 Sketch of front stitch patterns of the reconstructed 1936 sweater.

Fig. 16 Sketch of sleeve stitch patterns of the reconstructed 1936 sweater.

This garment has a clearly defined central panel and symmetrically arranged side panels. The stitch patterning is complex, and there are at least eight different twist and cable stitch variations on this sweater, as well as textural patterning. Looking at the stitch patterns on the garment in detail, with reference to Mary Thomas’s descriptions, highlights the pattern variations and complex repeats found on this single garment. The sketches shown in Figures 15 and 16 represent some of the knitted lines in these patterns.

The patterns include two variations of a diamond lattice, one using a two-stitch twist and the other a four-stitch cable. The four-stitch cable lattice, or travelling rib, has moss-stitch texture within the outer diamonds and that of reverse stocking stitch within the centre diamonds. This texture beautifully echoes the moss-stitch diamonds that are visible on the outer sections of the front of the sweater. These diamond lattices form the centre panels of the sweater’s front and sleeves. The four-stitch cable lattice on the front is bordered by a five-stitch rope cable on each side. On the sleeves, the two-stitch-twist lattice is also bordered by a rope-style cable, but, in this case, it consists of two-stitch twists. Although the positioning of the rope cables on the front and sleeves is symmetrical, all of the twists have been worked in the same direction on each side of the centre panel, rather than as mirror images, with opposite twists.

Working outwards from the centre, the next pattern panels are combinations of twisted stitches. One combination forms a twisted stitch, diamond-column design with a twisted stitch rib pattern in the centre. This type of twisted stitch rib is made by knitting into the back of the stitch, making it appear more prominent. The column is placed on a stocking stitch background and has the same appearance on the front and the sleeves. The other combination forms zigzag lines of two sets of two-stitch twists on a reverse stocking stitch background. Again, the zigzags are worked in the same direction, rather than as mirror images. The welt comprises twisted stitches that are crossed on every eighth row. In Mary Thomas’s description, the stitches are slipped on to a match (rather than a wire or spare needle) and dropped to the front of the work to create the twist.

Aran-style knitting became less popular both during and after the years of the Second World War. One reason for this was that twist and cable knitting uses a considerable amount of yarn for a single garment. Wartime rationing meant that knitters had access to only extremely limited amounts of yarn. Knitters at that time devised many clever ways to make their limited supply of yarn go further. After this time, as yarn became more freely available again, twists and cables began to re-emerge as design features; nevertheless, the way that the stitch patterns were used began to change.

Fig. 17 1959 knitted cable sweater. (KCG Collection; photo: Barbara Smith)

The sweater shown in Figure 17 was knitted from a pattern originally published in Woman’s Weekly magazine in 1959. This sweater has a central panel, with symmetrical stitch-panel placement on each side of this panel, so it could be considered a traditional Aran sweater.

Fig. 18 Sketch of knitted detail on the 1959 sweater.

The knitting techniques used in this sweater, such as the bramble-stitch centre panel, the travelling, twisted stitch Vs and the double cable lines, were all commonly found on Aran-style garments. However, the square neckline and the shawl collar were not classic Aran constructions. These features, highlighted in the sketch in Figure 18, show the influence of fashion at this time. The cable designs found on the 1959 sweater are in the style of Aran knitting, but the pattern is beginning to move into new design territories. Designers were using the Aran techniques in new ways and with different weights of yarn. For example, in 1957, the yarn company Patons had released a series of Aran-style patterns that were all designed for 4ply yarn.

By 1965, Patons had developed a heavier-weight knitting yarn called Capstan that was specifically for Patons Aran patterns. This yarn, initially available only in natural white, either oiled or scoured, proved so popular that by 1968 it was made available in several different colours. At around the same time, the Patons Aran Book was published. Although other ways of using twist and cable techniques in knitting had emerged, it was the huge popularity of Aran knitting in the late 1960s that set the style of what is now referred to as ‘classic’ Aran knitting.

The influence of fashion trends on all knitting is also seen from this point onwards. In the 1970s, bright neon colours made their way into hand-knitting patterns and, in the 1980s, oversized shoulders resulted in many cable sweaters being knitted with drop shoulders. A 1984 sweater from the KCG Collection, shown in Figure 19, demonstrates a clear inspiration source and the use of Aran techniques, but the result is very different when compared to the previous examples.

Fig. 19 1984 Knitted wheatsheaf sweater. (KCG Collection; photo: Barbara Smith)

In the 1980s, picture knits were extremely popular, and the wheatsheaf sweater shown in Figure 19 is part of this fashion trend. The pattern is from a magazine supplement of The Sunday Times from 9 December 1984, also held in the KCG Collection. The Sunday Times describes the sweater as a ‘wonderful modern interpretation of the traditional Aran’. The free pattern is one of two on offer to readers. The suggested yarn is Wendy Kintyre pure Aran wool. Interestingly, the second, much requested, pattern is a winter jacket designed by the Bishop of Leicestershire, Richard Rutt.

As with the previous sweater examples, the wheatsheaf sweater fulfils many of the requirements for it to be called Aran. The colour and weight of the yarn, the range of knitting techniques used and some of the garment construction methods can all be defined as Aran. However, this sweater is clearly different to a classic Aran sweater.

Fig. 20 Sketch of knitted and embellished detail on the wheatsheaf sweater.

The wheatsheaf image itself is a very traditional symbol, and it is placed on the garment as the central panel, with additional symmetrical pattern panels on each side. The details are depicted in the sketch shown in Figure 20. However, the pictorial nature of the knitted wheatsheaf motif is very different to the Aran patterning of the previous example garments. Although knitted to include twisted stitch ropes, the design also incorporates additional surface-embroidery techniques. The cable patterning on each side of the central panel is worked in the style of a horseshoe or print-o’-the-hoof cable. The textured underside of the sleeves and the outer sides of the front are knitted in moss stitch, contrasting with the reverse stocking stitch background of the wheatsheaf motif. The cuffs, lower edging and neckband contain a combination of a zigzag travelling cable with bobbles and two-stitch twists worked as ropes.

The three garment examples from the KCG Collection highlight a few of the ways in which Aran style evolved during the twentieth century. The stitch-pattern combinations of classic Aran knitting originated with highly skilled, individual knitters experimenting with their knitting. Their ideas were shared, deliberately or accidentally, at a national and then international level throughout the twentieth century, with fishing boats taking gansey patterns to new destinations and design interpretations from other countries appearing in national newspaper supplements and magazines. Additional changes in the use of twist and cable patterns occurred in response to widening yarn availability, increased consumer demand for new knitting patterns and ever-changing fashion trends.

The continuing influence of twists and cables

This historical overview has included references to knitted samplers, garments and accessories that are held in several important textile collections. As well as forming the basis for research into historical knitting, these important items have themselves become the inspiration for new designs and directions in knitting. In recent years, knitted items containing twists and cables have been featured in several diverse exhibitions and within the collections of several renowned designers. In addition to being used as a reference point, these items have already generated and will continue to generate a multitude of new ideas when combined with other crafts and disciplines. This cross-fertilization into other areas of design reveals an exciting future for these most traditional of techniques.

In the exhibition Future Beauty: 30 Years of Japanese Fashion, held at the Barbican Art Gallery from October 2010 to February 2011, creative knitted garments featured alongside other examples of innovative Japanese fashion design. The impact of designers such as Rei Kawakubo and Tao Kurihara for the Tao Commes des Garçons label showed how, beginning in the 1980s and continuing until the present, Japanese designers have used traditional techniques in new and innovative ways. From Kawakubo’s large-scale sweaters with loosely woven cable structures to Kurihara’s use of underwear as outerwear, the approach of these influential designers was to deconstruct traditional ideas and construct a new style. Several knitted garments and accessories were featured in the exhibition, but one in particular showed this use of traditional techniques in a new way. An ivory, wool, knitted bodice and cable-knit shorts, designed by Kurihara for Tao Commes des Garçons for the Autumn–Winter 2005/06 season, were inspired by her detailed study of classic undergarments. The new designs had the appearance of delicate undergarments, but the features were completely reconfigured by using knitting techniques more usually associated with outerwear. The garments were knitted with bold, raised lines of twists and cables, as well as a travelling-stitch lattice filled with knitted bobbles. Crochet embellishment and laced ribbons completed the very delicate design that reflected the Japanese street style of the time.

Another Barbican exhibition, held in the summer of 2014, showed more examples of combinations of creative cables and twists and unexpected additional techniques. In The Fashion World of Jean Paul Gaultier: From the Sidewalk to the Catwalk, knitted twists and cables were displayed alongside high fashion.

The twists and cables were just one of the couture techniques used by the designer to create his visionary collections that featured on the catwalks throughout the world.

The importance of items in museum collections was highlighted in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York, USA, from October 2017 to January 2018. This exhibition featured an iconic Aran sweater from the Country Life collection of the National Museum of Ireland. This 1942 sweater is one of several that have been studied by historians and researchers exploring the history and impact of Aran design. This example has similar design features to the reconstructed sweater from the KCG Collection looked at earlier in this chapter. In the MOMA exhibition, called Items: Is Fashion Modern?, the sweater is displayed as an example of a classic design with enduring popularity. It is one of 111 items of clothing and accessories, each selected to explore the notion of the past, present and future of world-renowned designs. This historically important Aran sweater, with its complex combinations of twists and cables, was displayed alongside other iconic designs such as Levi’s® 501® jeans, the Breton shirt and the little black dress, clearly showing the enduring popularity of Aran style. The inclusion of this 1942 Aran sweater in the context of global design is a reminder of the endurance of twists and cables throughout fashion history.

These examples illustrate the nature of knitted twists and cables changing over time. The techniques used remain constant, but the way that they are applied has developed in many fascinating ways. This change of use and context reflects the skill and creativity of the designers involved. However, all of the twist and cable techniques owe their origin to the knitters and designers who developed the skills and ideas that form the link between all of these designs. Without the old Scotch stitch, the ganseys and the Arans, these new directions in the fashion world would not have been possible. As with the fishing boats transporting gansey-sweater patterns across the British Isles, the museum displays provide another means for the deliberate or accidental sharing of ideas to promote new design directions.

CHAPTER 2

TERMINOLOGY AND TECHNIQUES

This chapter looks at twisted stitches and cables in detail, beginning with the definitions, moving on to the knitting actions needed to create the stitch movements, then looking at the effect on the knitted fabric and concluding with how to work from a knitting chart.

Knitted lines

A knitter’s sketchbook is all about the interpretation of pattern by using inspiration sources. Knitted lines and shapes are the building blocks for interpretative designs. The lines and shapes are formed by using a variety of widths of knitted lines. It is therefore essential to make a distinction between the fine lines of twisted stitches and the broader lines of cables, as the width of the line in the knitting is very important.

Fig. 21 Examples of widths of lines in knitting.

The twists and cables can be considered the equivalent of the strokes of pens, pencils or brushes. Narrow lines of twisted stitches can draw a delicate image similar to that achieved with fine pencil lines. A wide, chunky, multiple-stitch cable evokes a broad brushstroke. The knitted swatch shown in Figure 21 demonstrates how changing the number of foreground stitches changes the width of the knitted line, from the single twisted stitch on the right to the broad cable on the left. Although all of the stitch movements could be called cables, this distinction between the fineness of the lines will be clearly defined in the following section.

The knitted lines in the swatch shown in Figure 21 have been worked on the foreground of the knitting, which in this example is the right side of the work. The background stitch pattern, again on the right side of the swatch, is also critical to the overall design. The background stitches are like the paper that is used for drawing on. In the same way that the choice of paper will change the look of a drawing, the choice of background stitch will affect how the foreground stitch pattern of the cables and twists will appear. Choosing to work on textured or smooth paper has a similar result to that of choosing to work on a moss-stitch or stocking stitch background.

Describing twists and cables

Before beginning a pattern, the most important advice for any knitter is to read the abbreviation definitions carefully. Never assume that any particular symbol means to perform the same action as that described in a context that you have previously encountered the symbol; different publications and patterns can use the same symbol to mean a completely different stitch movement. This book uses a consistent series of symbols and definitions throughout. The symbols are all part of the Stitchmastery charting software. These symbols allow the knitter to ‘see’ the stitch movements, both in the format of charts and as the stitches appear within the knitted swatches. New symbols will be explained as they are used, and the terminology will be clearly explained. There is a full list of all of the symbols and definitions at the back of this book (see Abbreviations).

Twists

There are several definitions of a twist or twisted stitch, and all depend on the context of the stitches being worked. A twist can be a single stitch crossed over another single stitch or a group of stitches. This type of stitch movement can also be called a cross stitch or travelling stitch. The stitch movement can be a simple exchange of places between neighbouring stitches or a complex lattice worked over many rows. The twisting can be worked in the same position within the fabric, to create a vertical line, or can be linked over several rows across the fabric, to create diagonal lines. The twisting can be to the left or the right and be worked in a variety of different stitch textures. In many cases, this kind of stitch movement is referred to as a cable. The term ‘twisted stitch’ can also describe a stitch that results from the action of working into the back of that stitch, creating a twist in that particular stitch. Working this kind of twisted stitch throughout the knitting creates dense knitted fabric but without any crossing of stitches over each other.

There is a strong case to label all of the lines resulting from the movements of groups of stitches as cables. However, for this book, the distinction between the fine lines created by single-foreground-stitch movements, for delicate stitch patterning, and the broader lines created by moving larger groups of multiple stitches is very important. This book therefore defines a twisted stitch as a single foreground stitch that is moved or crossed over one or more background stitches. The knitted line on the right-hand side of the fabric shown in Figure 21 is an example of a twisted stitch.

Cables

A cable can be defined as a group of stitches that are crossed over another group of stitches. The group of foreground stitches can be worked over any number of background stitches and in a variety of textures. Cables are similar to twists, as they involve an exchange of position of the stitches. Cables are usually named after the number of stitches involved and the direction of movement of the front stitches. In this book, the cable stitch movements supply a huge variety of width of foreground line.

Cables are also sometimes referred to as travelling stitches. A travelling stitch moves in a similar way to a cable, usually over several background stitches. In her 1979 book, Patterns for Guernseys, Jerseys & Arans, Gladys Thompson makes a distinction between cables and travelling stitches in the section about Aran knitting. Cables are described as being worked amongst the travelling stitches that run across the knitted-fabric surface. The stitch movements involved are the same movements as used in a vertical cable column; however, the effect is to create a moving line.

Cable stitch movements in this book therefore refer to two or more foreground stitches being moved over one or more background stitches. The stitch movement may be repeated in a vertical column or used to move the foreground stitches across the knitting. The knitted lines in the centre and on the left-hand side of the fabric shown in Figure 21 are examples of cables.

Front and back versus left and right