26,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

What is that lace? How old is it? Has it been made by hand or machine? What would it have been used for? These are the types of questions that this practical guide sets out to answer. Lavishly illustrated, it shows you how to identify the sort of lace that you might find hiding away in drawers and cupboards, or buy at a vintage textile fair. It deals predominantly with the hand-made and machine laces of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Topics covered include: an introductory survey of the different types of lace, their history and construction; guidelines for a systematic approach to lace identification and advice on cleaning and storage; chapters on the different types of lace: bobbin lace, needlelace, craft laces such as crochet and tatting, machine lace and lace based on tapes and nets. There are exercises on distinguishing similar pieces of lace made using different techniques and there are illustrations of how lace has been used and of some of the tools used in the making. Written by experienced lacemakers, Gilian Dye and Jean Leader, it presents items from their own collections to illuminate and inspire others who wish to know more about this fascinating textile. Lace Identification is a complete guide to the beauty of this stitch craft, and will richly reward all those who study the treasures they may own.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 232

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

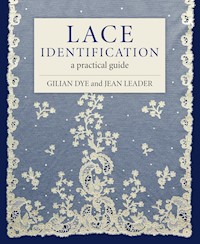

LACE

IDENTIFICATION

a practical guide

Stole of Brussels Application lace.

LACE

IDENTIFICATION

a practical guide

GILIAN DYE and JEAN LEADER

First published in 2021 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

This e-book first published in 2021

© Gilian Dye and Jean Leader 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 867 2

AcknowledgmentsThis book would not have happened without the help of our families and friends who have supported us over many years, providing encouragement, examples for the illustrations and assisting with dating and other research. Particular thanks go to Barbara and Tony Tapper, Barbara Pannel, Adrienne Thunder and Susan Wallace for substantial donations to our collections. Also to the lace volunteers at the Discovery Museum in Newcastle (Jo Davis, Ann Hotchkiss, Karin Jackson and Val Lloyd) for creative discussions.

We are also very grateful to the teachers who have passed on their technical lacemaking skills and historical knowledge, the students who have asked difficult questions and curators and others who have provided access to lace collections large and small.

Front cover: A long stole of Carrickmacross lace, probably made at the end of the nineteenth or beginning of the twentieth century. The many shamrocks in this beautifully designed piece confirm the Irish origins. Other typical Carrickmacross features are the scattering of little dots (known as pops) across the background, the loops of thread around the outer edge and the spaces with decorative fillings.

Cover design: Design Deluxe

CONTENTS

Introduction

1

Types of Lace and Materials

2

Approaching an Identification

3

Continuous Bobbin Lace with Mesh Grounds

4

Continuous Bobbin Lace with Plaited Grounds

5

Non-continuous Bobbin Lace

6

Needle Lace

7

Net and Tape Laces

8

Craft Laces

9

Machine Lace

10

Spot the Difference

11

But What is it For?

12

Odds and Ends

Glossary

Time Line

Resources

Index

INTRODUCTION

Lace is part of our lives and has been for generations, from underwear to high fashion, from cathedral vestments to cottage tablecloths. Lacemaking began in Europe in the sixteenth century, the main techniques being needle lace (developed from cutwork embroidery) and bobbin lace (evolving from surface braids). The thread used was usually linen – occasionally silk or precious metal. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries lace became more varied and worn extensively by both men and women in the higher levels of society: it was an expensive commodity.

Four weeks after we agreed to write this book, Gil’s sister Barbara handed her a small cardboard box labelled ‘Narrow Lace Pieces’. The box, packed tight with lace, had been unopened since it came to her from her husband’s grandmother, Mrs Maud Tapper, who had married the Rev. Martin Tapper in June 1901. At the top of the box was a rather crumpled length of bobbin lace with a machine lace edging and below that a fine crochet cuff mounted on net. Looking a little deeper it was clear that the box held exactly the sort of small lace pieces that the wife of a country parson could have used and re-used at the beginning of the twentieth century, examples that we might want to include in a reference book of everyday laces. This picture includes many of the edgings and insertions from the box.

Early in the 1800s there was a transition from lace being accessible only to the wealthy, to lace finding a place in the wardrobes and homes of a growing and increasingly affluent middle class. This was helped by the lowering of prices as a result of the Industrial Revolution: first came machine-made net to serve as a basis for handwork, and then machine-made imitations of handmade lace. Middle-class women had more leisure time, and crafts such as crochet and tatting became extremely popular.

The twentieth century saw the demise of handmade lace as an industry, although the last fifty years have seen a revival of lacemaking as a recreational pursuit. More recently there has been increasing interest in working in colour and non-traditional materials, in addition to traditional white lace worked in linen or cotton thread. While many lacemakers still enjoy the challenge of interpreting traditional patterns, others are using lace techniques for pictures, hangings and three-dimensional objects. Some of these items might not be immediately recognizable as lace, but a closer look will reveal the centuries-old techniques.

Most lace purchased new today is machine made, but large amounts of older lace can be found tucked away in drawers and boxes, or on sale at vintage fairs or other second-hand outlets. Some of this lace will also be machine made, but much will have been made by hand using a variety of techniques.

This book started life as a straightforward guide to the laces of the past 200 years. Not the top-of-the-range seventeenth-century exhibition pieces held in the major textile and costume collections, but the sort of lace that is likely to be treasured as a family heirloom, find its way into a local non-specialist museum or turn up in a charity shop. As the material came together we realized that it would be helpful to put the lace into context – social, domestic and commercial – so this is what we have tried to do.

Most of the illustrations are of items in the authors’ collections. Neither of us is an active collector; occasionally we buy interesting pieces, but many items have been gifts from people who are keen to pass on lace that they know will be cared for and shared with others on a formal or informal basis. Our thanks go to these people, many now anonymous, and to the friends and relatives who have allowed us to include illustrations of their lace.

We hope this book will be of interest and help to collectors, to those trying to make sense of lace they have inherited or are sorting for a charity, and to museum staff who have no specialist textile background, but need to understand the lace in their stores before they can make it available and accurately labelled for their visitors.

CHAPTER 1

TYPES OF LACEAND MATERIALS

Needle lace and bobbin lace are the two classic laces, sometimes considered the ‘real’ laces. Needle lace is a form of free embroidery, made with a needle and a single thread. In contrast, bobbin lace is more like plaiting or weaving, made by manipulating multiple threads, each wound on a separate handle known as a bobbin. Both bobbin and needle lace evolved during the 1500s and many distinct styles have emerged over the succeeding centuries (see Chapters 3, 4, 5 and 6).

A nineteenth-century collar which combines bobbin and needle lace. The central panel (the back of the collar) is needle lace with flowers and leaves of closely worked stitches set in a background of open mesh. At each side of the collar is a row of four small circles that are also needle lace. The woven look of motifs in the rest of the collar indicates that these are bobbin lace.

Other types of handmade lace are often described as craft laces. Some of these have been worked commercially, but most of the pieces you find will have been made in the home. Knitting and crochet are the most widely practised forms of craft laces (Chapter 8).

Working a needle lace motif. On the left a pattern has been tacked to a fabric backing, then two threads couched along the outline of the motif, with stitches going through both pattern and backing. On the right the motif has been filled with rows of buttonhole stitches, linked at each end of the row to the couched outline, but not going through the pattern. Additional threads laid over the couched outline are now being buttonhole stitched in place to give a raised outline and finish the lace. Once the stitching is complete the lace will be removed from the support by snipping the couching threads.

Working bobbin lace. A pattern, known as a pricking, is pinned to a firm pillow, then bobbins wound with thread are used two pairs at a time to work the stitches, which are held in place by pins placed in holes in the pricking. The lace being worked is an English bobbin lace known as Bucks Point.

Hand-knitted lace is worked in rows or rounds of interlinked loops using two or more needles and a single thread. This doily, worked in cotton, is typical of lace knitted in the home for domestic use. Knitted lace shawls, scarves and baby clothes have been worked both commercially and domestically in fine, soft wool.

Filet (also known as lacis) is based on hand-knotted square-mesh net. In the earliest form designs are embroidered using a simple darning stitch. A greater variety of stitches were used when the craft was revived in the Victorian period. Stitching is easier when the net is stretched in a frame.

Crochet is worked with a single thread and a small hook. A basic looped stitch produces a simple chain; other stitches are built up with additional movements. Many crochet items are assembled from motifs; this example has nine flowers with four small connecting squares and a chain-stitch border with picots. Knitted lace is often finished with a similar crochet chain.

Tatting is a knotted lace worked with a small shuttle. Designs are composed mainly of rings and arcs, with picots that are both decorative and a means of linking different sections.

Tenerife lace is composed of linked needle-woven circles. The technique developed from a form of openwork embroidery known as sol lace. It is worked on a temporary support, such as a circle of pins on a pincushion.

There are other forms of craft laces which are based on woven fabric or machine-made net, also various laces that combine two or more techniques, for example needle lace with machine-made tapes.

Three examples of machine-made lace. The lace at the top has a mesh background and open-work areas which may give the appearance of handmade bobbin lace, but closer inspection shows rather muddled threads in the mesh and tightly packed threads in the more solid areas; these are typical of lace made on a Leavers machine. Lace worked on a Barmen machine can be more difficult to distinguish from handmade bobbin lace, but the extreme regularity of the repeats in the second lace gives a clue that this piece is also machine made. The fuzziness of the third lace gives it away as being chemical lace – worked by machine embroidering on a background that was then chemically dissolved away.

Experiments in using machines to make lace started towards the end of the eighteenth century and by 1809 it was possible to produce a hexagonal net that became the foundation for the wide variety of embroidered and appliquéd laces described in Chapter 7. Over the following decades machines were adapted to produce patterned nets. Then a stream of technical developments led to a variety of machines all aiming to copy existing lace or create new styles, to satisfy an ever-increasing demand for fashion and household fabrics (Chapter 9).

Making lace by hand continued alongside developments in machine lace until the end of the nineteenth century, by which time neither bobbin lace nor needle lace were commercially viable except at the very top end of the market. The small industries that produced knitted and crochet lace, or net- or fabric-based open work were also struggling, but many of these continued as domestic crafts until well into the twentieth century, enjoying intermittent revivals up to the present day. Machine lace had its ups and downs over the twentieth century, never completely losing its popularity for underwear and household furnishings, and now in the twenty-first century making considerable impact on the catwalks and in the online stores.

Sketches of collars taken from fashion plates and other sources where the date of a collar is known.

In Britain there was a great revival of interest in handmade lace in the 1960s and 70s with classes and new books, and a general mixing of ideas and techniques including use of coloured threads and non-traditional materials. Lacemaking has struggled in the twenty-first century, but there are signs that the internet may be helping to reverse this trend.

Dating lace

This is an area that is notoriously difficult. It is usually possible to give the earliest date that a particular type of lace was made, but similar lace may have been made at any time up to the present day and in any part of the world. Only on rare occasions will an item have a clear date provenance. Sometimes a knowledge of fashion history may help since the style of an item can give a clue to the age of the lace involved, but lace is a valuable fabric and often re-used, sometimes combining pieces of different types and ages – something that is not always obvious at first sight.

The focus for this book is lace that has been made since the end of the eighteenth century, the time when machine-made lace began to compete with handmade bobbin and needle lace. There is a time line at the end of the book that gives dates for the first appearance of certain laces and some of the social and other factors that influenced the making and wearing of lace.

Terminology

Lace has been made and used in many ways, in many places and over many hundreds of years, so it is not surprising that the terminology can be confusing. In the Glossary towards the end of this book we have given the meanings of specialist words we use.

Materials

Lace can be made with any material that can be cut, drawn or twisted into a thread. Most of the early lace was worked in linen (spun from flax). Coloured silk and metal threads were also used extensively for bobbin lace in the sixteenth and seventeenth-centuries. Delicate bobbin and needle laces made in the eighteenth century required exceptionally fine linen threads, the best being produced in Flanders. Cotton started to replace linen for working bobbin and needle laces in the middle of the nineteenth century.

Fine wool was the yarn of choice for knitted lace scarves and shawls in the nineteenth century, and wool and other natural fibres such as bamboo are now being used for bobbin lace scarves. Some of the heavier bobbin lace trimmings popular in the Victorian period were also worked in wool.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, silk was the only fine thread available that was smooth and strong enough to cope with the stresses of working machine net and lace. A strong, smooth cotton thread became available around 1810 and was the yarn of choice for machine laces until synthetic threads took over in the 1950s.

It is sometimes possible to distinguish between cotton and linen by feel or looking at a thread under magnification – cotton threads are usually smooth, while linen threads have little bumps. Silk and artificial silk are difficult to distinguish by look and feel, but silk is an animal protein and artificial silk is plant-based cellulose so if you are prepared to sacrifice a small amount of thread, you can try a burning test – silk will smell like burning hair, artificial silk (rayon) like burning paper. For detailed information about the structure of threads see Pat Earnshaw’s Threads of Lace from Source to Sink.

Today most machine lace is made with one of the many synthetic threads, or a blended yarn such as polyester and cotton, while a lacemaker might utilize anything from the traditional silk, linen and cotton threads to wire, found objects or strips of plastic.

Thread structure and thickness

Most bobbin laces and many early needle laces were made with 2-ply linen thread, occasionally silk, and later cotton thread was used. Some techniques, such as crochet, require a firmer, more rounded thread; this is usually achieved by twisting together three 2-ply threads. Synthetic threads are usually produced as continuous filaments, which are twisted to produce similar structures.

Most 2-ply threads used by lacemakers are S-twist, so the line of the twist is in the same direction as the diagonal of a capital S – as in the example on the left. Twisting a group of S-twist threads together results in a Z-twist cord (on the right).

Stranded embroidery cotton (also known as embroidery floss) is not a traditional thread for making lace, but it is becoming increasingly popular for coloured lace and it is a thread that many people know, so we are mentioning it here as a rough guide to the thickness of threads used for making lace. The majority of laces are made with threads that are in thickness between one and four strands of embroidery floss, but there are a number of machine nets and bobbin laces, such as Honiton, that are worked with finer threads.

Place of origin

Unless otherwise stated lace described here was originally made in Europe, but lacemaking has now spread worldwide, with numerous combinations of styles and techniques. Lace is often named after a location where it was made – Honiton, Bruges, Alençon and so on – but this defines neither where all lace of that name was made, nor the style of all lace made in that place.

CHAPTER 2

APPROACHING AN IDENTIFICATION

Lace is a complicated subject. This is only to be expected with a fabric that has been made in the home with a pair of knitting needles or in a vast factory with complex machinery. It is a fabric that has adapted over five centuries to the vagaries of fashion and, in the past 200 years, to rapid developments of technology. This can make identification tricky and sometimes it is necessary to record an item as being ‘x type’ or ‘probably y’. The good news is that certain types of lace turn up more frequently than others, and the common laces often have features that make them relatively easy to identify; some examples are given later in this chapter. Also, the more lace you study, and preferably handle, the easier identification becomes. For study purposes small pieces, or those that are in poor repair, are often as interesting as larger items.

A group of machine and handmade laces showing a variety of styles and techniques.

Table prepared for a study session. In addition to the lace there is the lace identification app prepared by Jean and David Leader, tape measure, notebook and pencil, and two means of magnification – a magnifying glass and a Phonescope – all laid out on dark purple jersey fabric.

If you are working on the identification of a batch of laces then it is worth getting yourself organized. In a museum setting a curator’s requirements would be that you wash your hands, remove jewellery and other items that might catch on the lace, avoid fluffy jumpers and keep food and drink well clear of your study area. This is good practice when working with your own collection. Obviously, it is not practical when rummaging through a box at a car boot sale; there you must trust your instincts and be prepared to pay a reasonable sum for a piece of interest that can be examined later at your leisure.

If no mannequin is available a polo-neck sweater on a padded hanger provides a useful substitute for viewing a collar.

Putting a baby’s bonnet on a large wine glass allows you to see its shape, and also in this example to see what appears to be a dirty mark on one corner – closer inspection shows that this is the remnant of a coloured ribbon. A coloured background is needed to show detail of stitching, which is provided in the second picture where a soft ball covered in dark green fabric has been balanced on a jar.

Ideally you will have good lighting, a dark background on which to view light-coloured lace and a light background for black lace. Some simple props for collars, bonnets and other three-dimensional items can be helpful.

Other useful items to have to hand include: notebook and pencil (avoid pens as they could mark the lace); reference book(s) and/or identification app; tape measure; magnifier. At one time we relied on a pocket magnifier (loupe) or linen tester to see the detail of lace stitches, these are still useful tools, but digital cameras on our phones or tablets can be equally helpful.

Start by looking at the whole piece. What is the overall shape – is it a complete item (for example a collar or table mat), a single repeat, a short or long length? Is it a border (edging) or an insertion? Look at it from different angles, and if it is an item such as a collar try to view it on an appropriate support. If it is your own lace you can try it on yourself or a friend, but this is not usually permitted in a museum – there you might have mannequins you can use. (Be aware that some mannequins are very strange shapes.)

A roll of coloured fabric slid inside a sleeve allows you to see the detail of stitches, while something as simple as a ball or pudding basin balanced on a jar allows you to see the way a bonnet would look in use. Be inventive in your choice of support, but also be careful so you don’t damage the lace in any way by catching it on sharp edges or allowing dirt or colour to be transferred from the background.

Make a note of anything you know about the history of the piece, including when and where you acquired it – this is its provenance (preparing this book would have been a great deal easier if we had followed this advice twenty years ago!). However, be wary of family tradition unless you have documentary evidence – it is a real bonus when you can match up a piece of lace with a family photo.

Then look at the detail.

The relevance of the following questions will become clear as you read about the structure of different laces in the chapters that follow.

• Does the lace appear to be worked as a continuous piece or assembled from separate sections?

• Do the front and back look similar?

• Is there a net (mesh) background? If so, what shape is the mesh?

• Are there gaps between motifs that are crossed by connecting bars? Do the bars have decorative loops (picots)?

• Are there picots along the outside edge?

• Are all the threads the same thickness?

• Can you see a tape (braid) that meanders through the lace?

• Does the piece appear to have been altered in any way? Are there places where the lace is coming apart?

• Is the lace mainly composed of looped stitches?

• Is there anything that might make you think it is machine lace? A fuzziness? A ribbed effect? The same error on every repeat? Very wide pieces with no sign of a join?

• Is there a strip along one edge that looks very different from the rest?

This bobbin lace edging is composed of separate motifs linked by bars decorated with the little loops known as picots, and there are also picots all along the lower edge. The strip along the top is of a different density worked with a different thread and almost certainly machine made. Borders, collars and other items often have a separate strip stitched along one edge, which is known as an engrelure and is there to protect a more valuable lace so it is not damaged when the lace is removed for washing or re-use.

After studying the overall look of a piece you may need a more detailed view of the structure before reaching a decision on identification; this is where magnification may be required.

A Phonescope is an inexpensive gadget that fits over the lens of a mobile phone and allows close-up photos to be taken – very helpful when studying background stitches. (Phonescopes can be found online and in museum shops and the larger garden centres.)

Many laces are composed of relatively dense pattern areas – known as clothwork – set in a background mesh – known as a ground. Some types of lace have many varieties of ground; illustrations at the end of this chapter, all taken with a Phonescope attachment for a mobile phone, show a variety of hand- and machine-made stitches. There is also a page showing snapshots of nine common laces laces that you are likely to find in a general collection. Each lace is described in more detail in the relevant chapter. (Illustrations are not to scale.)

Record keeping

Once you start building up a collection it is a good idea to start an organized record of the lace you own. There are several ways to approach this. You might start with a notebook making notes on each of your pieces, perhaps a page per item, written as each piece is studied, but leaving space for additional information. The disadvantage of this approach is that as the collection becomes larger it will become more difficult to find individual records.

Using a loose-leaf file or a pack of index cards instead of a notebook will allow sorting of records into sections, for example according to type of lace (bobbin, needle, crochet, machine…) – or type of item (edging, doily, collar, undergarment…). Similar records can be kept electronically, either as simple Word documents, or in more specialist programs that will allow the use of key words to search the records – for example to find details of all your crochet collars.

The two record cards show two different approaches to recording an item of lace. The one at the top uses a database program that could be used for museum records, with words in bold appearing on every card. The more informal approach of the second card might be more appropriate for a small personal collection.

The record cards shown both give the type of object and style of lace, together with the size and an indication of the lace’s provenance. Both say when the lace was acquired, and both have space for adding additional information – either on the back of the card, or at the bottom of the page if this is an electronic record. This is the bare minimum of information to include. How much other information you record depends on the type of item, the size of the collection and how you expect to use it.

RECORD CARDS – SOME SUGGESTIONS FOR HEADINGS

Location – where the lace is stored.

File – category of item, for example lace edging, pattern, bobbin, collar…

Identity number – any item accepted into a museum is given a unique ‘accession number’, for example 2020/009, which indicates that it is the ninth item acquired in the year 2020. This number would be recorded on the item’s packaging and a label attached to the item itself.

No. of items – a pair of cuffs, for example, would be recorded as 2 (in this case they might have accession numbers 2020/012a and 2020/012b).

Date – there are four places on the card that ask for a date; the first is the date the item was made, the others are records of when things have happened within the collection.

Colour