33,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Serie: AutoClassic

- Sprache: Englisch

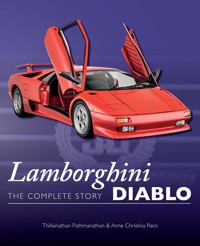

This book examines the Diablo in detail, starting with Ferruccio Lamborghini's objectives for his eponymous supercar company and his diktat that it eschew racing, which would go on to heavily influence the Diablo's design and development, even though the founder had long since left the company. Each of the model variants is examined in detail, as are the socio-politico-economic factors that that made designing and developing the Diablo imperative and unavoidable , and which forced the Sant' Agata works into making evolutionary modifications as well as introducing radical innovations over the course of the Diablo's long reign. Written by two passionate and deeply knowledgeable owners who for over two decades have run two wedge shaped, spaceframe, Bizzarrini-engined Lamborghini flagships, this book also delves into pre-purchase considerations, the Diablo's known foibles and the value of a pre-purchase inspection, before discussing the buying process, the trials and tribulations of periodic servicing, preventative maintenance, and garaging, after which it shares the sheer elation and exhilaration of actually piloting a Diablo.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 355

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Other Titles in the Crowood AutoClassics series

Alfa Romeo 105 Series Spider

Alfa Romeo 916 GTV & Spider

Alfa Romeo 2000 and 2600

Alfa Romeo Alfasud

Alfa Romeo Spider

Aston Martin DB4, 5, 6

Aston Martin DB7

Aston Martin V8

Austin Healey

Austin Healey Sprite

BMW E30

BMW M3

BMW M5

BMW Classic Coupes 1965–1989

BMW Z3 and Z4

Citroën Traction Avant

Classic Jaguar XK – The Six-Cylinder Cars

Ferrari 308, 328 & 348

Frogeye Sprite

Ginetta: Road & Track Cars

Jaguar E-Type

Jaguar F-Type

Jaguar Mks 1 & 2, S-Type & 420

Jaguar XJ-S

Jaguar XK8

Jensen V8

Land Rover Defender 90 & 110

Land Rover Freelander

Lotus Elan

Lotus Elise & Exige 1995–2020

MGA

MGB

MGF and TF

Mazda MX-5

Mercedes-Benz Ponton and 190SL

Mercedes-Benz S-Class 1972–2013

Mercedes SL Series

Mercedes-Benz SL & SLC 107 Series

Mercedes-Benz Saloon Coupé

Mercedes-Benz Sport-Light Coupé

Mercedes-Benz W114 and W115

Mercedes-Benz W123

Mercedes-Benz W124

Mercedes-Benz W126 S-Class 1979–1991

Mercedes-Benz W201 (190)

Mercedes W113

Morgan 4/4: The First 75 Years

NSU Ro80

Peugeot 205

Porsche 924/928/944/968

Porsche Boxster and Cayman

Porsche Carrera – The Air-Cooled Era

Porsche Carrera - The Water-Cooled Era

Porsche Air-Cooled Turbos 1974–1996

Porsche Water-Cooled Turbos 1979–2019

Range Rover First Generation

Range Rover Second Generation

Range Rover Third Generation

Range Rover Sport 2005–2013

Reliant Three-Wheelers

Riley – The Legendary RMs

Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud

Rover 75 and MG ZT

Rover P5 & P5B

Rover P6: 2000, 2200, 3500

Rover SDI

Saab 92–96V4

Saab 99 and 900

Shelby and AC Cobra

Subaru Impreza WRX & WRX ST1

Sunbeam Alpine and Tiger

Toyota MR2

Triumph Spitfire and GT6

Triumph TR6

Triumph TR7

Volkswagen Golf GTI

Volvo 1800

Volvo Amazon

Dedication

To Nallini Pathmanathan, Supreme Court Judge,Master of Middle Temple, sibling and surrogate parent.

First published in 2023 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2023

© Thillainathan Pathmanathan & Anne Christina Reck 2023

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 4245 0

Cover design by Blue Sunflower Creative

CONTENTS

Introduction

Timeline

CHAPTER 1FERRUCCIO LAMBORGHINI AND HIS EPONYMOUS SUPERCAR COMPANY

CHAPTER 2THE COUNTACH INFORMS THE DIABLO

CHAPTER 3PROGETTO 132: A STAR IS CONCEIVED

CHAPTER 4THE ORIGINAL DIABLO: PURITY EXEMPLIFIED

CHAPTER 5BUILDING THE DIABLO

CHAPTER 6DIABLO VT: RADICAL EVOLUTION

CHAPTER 7DIABLO SE30: THE ANNIVERSARY ROAD RACER

CHAPTER 8DIABLO SV: THE LIGHTWEIGHT LEGEND

CHAPTER 9DIABLO ROADSTER: A SANT’AGATA FIRST

CHAPTER 10THE SECOND GENERATION VT, VT ROADSTER AND SV: AUDI FACELIFTS THE 1999 MODEL YEAR DIABLO

CHAPTER 11DIABLO GT: SCION OF A RACING LINEAGE

CHAPTER 12DIABLO 6.0 VT: VW-AUDI REIGN SUPREME

CHAPTER 13MURCIÉLAGO: THE NEXT IN LINE

CHAPTER 14RANDOM MUSINGS OF A DILETTANTE

Appendix: Lamborghini Diablo Specifications

Acknowledgements

Index

INTRODUCTION

The Lamborghini Diablo was the product of three immutable factors: the supercar heritage of Sant’Agata Bolognese, the unrelenting pressure from new technology adopted by rival supercar manufacturers, and the ever-fluid and inexorably forward-moving social, political, economic and environmental influences of the late twentieth century. The Diablo story can only truly be understood by studying each of these elements.

If Sant’Agata readily gained entry into the very highest echelons of the supercar world by way of the Lamborghini Miura, this Emilia-Romagna based manufacturer definitively established its name by designing and building another of the defining supercars of all time, the refulgent Lamborghini Countach. The Miura’s supposedly novel mid-engine layout had been seen in earlier racing and road cars, but the Countach’s revolutionary south-north engine-gearbox orientation, its extreme wedge shape and its startling scissor doors were all unique and had not been seen before in any production car. With these features the Countach started a dynasty that continues today, and the Lamborghini Diablo was the first evolution of this Countach bloodline.

But the Countach had faults and foibles aplenty. Rival supercar manufacturers stood eager and ready to topple this acknowledged King of the Supercars. The Countach was largely early 1970s technology, and teams in Stuttgart and Maranello, in 1985 and 1987 respectively, demonstrated just how far the ‘Science of Supercars’ had progressed when they launched the Porsche 959 and the Ferrari F40. By the late 1980s the Countach had been comprehensively outclassed in many different areas, but most notably in the field of aerodynamics. A completely new replacement car, which came to be the Lamborghini Diablo, was the only pragmatic solution. If the Countach begat the Diablo, then aerodynamics was its midwife.

Lamborghini could call upon expert designers, highly specialised engineers and skilled artisans from within its existing ranks to produce a worthy successor to the Countach. Money, or rather the lack of money, was also no longer a restraining factor. For much of its history Lamborghini had been shackled by financial woes, but not any more. While the Diablo was still on the drawing board, Lamborghini was bought by Chrysler. Given Detroit’s immense financial firepower, money would no longer limit innovation and progress at Sant’Agata.

The greater challenge facing Lamborghini was how to respond to the fluid demands of customers, politicians and activists. The Diablo had to be faster, and faster accelerating, than the Countach: customers would accept nothing less, if only for bar-room bragging rights. The Diablo also had to be more spacious, more comfortable, more user-friendly and more reliable. Ralph Nader’s seminal 1965 treatise Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-In Dangers of the American Automobile still reverberated into the late 1980s, and politicians were forced to legislate on ever more stringent pedestrian, passenger and driver safety mandates. The Diablo had to accommodate these new government decrees, just as it had to entertain the fallout from the 1973 OPEC oil crisis, which demanded huge improvements in fuel efficiency. Similarly, strident calls for air pollution controls from environmental activists, that had started with William Wordsworth’s Romantic Movement in the nineteenth century, had morphed into the Earth Day protests of the 1970s, and there was no way a massive North America-based multinational like Chrysler could ignore, or swerve around, demands for less polluting cars.

Lamborghini certainly had its work cut out in designing, testing, developing and finally building the Diablo while still working within the limits of these multi-faceted constraints. Later in its production cycle the Diablo faced even more stringent legislation, as well as more advanced rivals like the Bugatti EB110 and the McLaren F1, both of which really pushed the technological envelope far forwards.

That the Lamborghini Diablo succeeded so spectacularly is a reflection of Sant’Agata’s inherent strengths. Today, more than twenty years after its debut, the Diablo still retains the power to startle and stupefy any driver, passenger or casual bystander.

TIMELINE

1916 Ferruccio Lamborghini born in Renazzo di Cento, near Bologna

1963 Automobili Lamborghini SpA presents its first car, the 350GTV, in prototype form

1964 Launch of the 350GT, the first production Lamborghini car

1966 The Miura makes its debut at the Geneva Motor Show

1971 The prototype Countach, the LP500, is shown on the Bertone stand at the Geneva Motor Show

1974 The first production Countach is delivered

1990 The Lamborghini Diablo, Sant’Agata’s replacement flagship for the Countach, makes its debut in January at the Sporting Club de Monte Carlo

1993 The four-wheel-drive Diablo VT is launched in March at the Geneva Motor Show. Limited edition Diablo SE30 launched in September

1995 The stripped-down Diablo SV makes its debut in March at the Geneva Motor Show. Lamborghini Diablo Roadster is launched in December at the Bologna Motor Show

1998 Now under the ownership of the VW-Audi conglomerate, in September Lamborghini presents a 1999 Model Year facelifted trio: the Diablo VT, Diablo SV and Diablo Roadster

1999 Diablo GT makes its debut in March at the Geneva Motor Show

2000 The Diablo 6.0 VT is launched in January at the Detroit Auto Show

2001 The Diablo’s replacement, the Murciélago, is presented in September on the foothills of a still-smoking Mount Etna in Sicily

CHAPTER 1

FERRUCCIO LAMBORGHINI AND HIS EPONYMOUS SUPERCAR COMPANY

The Lamborghini Diablo, in its earliest guises and most common forms, was the product of Ferruccio Lamborghini’s singular diktat that his supercar company should never make racing cars, or indulge in motor sport. It would be long after Ferruccio had relinquished his ownership of Lamborghini, more than three decades later in fact, that Sant’Agata finally broke with this policy and produced a track car. This first factory-sanctioned Lamborghini racing car was a Diablo derivative. The Diablo, however, like its illustrious predecessors the Countach and the Miura – and indeed its earliest ancestors, the 350GTV, 350GT, 400GT, Jarama and Espada – was conceived and designed purely as a road car. This remains a key defining feature of the Lamborghini Diablo.

Ferruccio Lamborghini: hemp farmer, schoolboy artisan, wartime mechanic, tractor manufacturer, Italian industrialist and supercar visionary.

Ferruccio’s influence also permeated through the Diablo by virtue of his shrewd appointments at the very beginning of the company’s history. Giotto Bizzarrini had designed Lamborghini’s stalwart 60-degree V12 engine in 1963, but a modernised version of this powerplant was used in the Diablo throughout its production life. Ferruccio quickly identified the very young Giampaolo Dallara as the most promising automotive engineer of his generation, and appointed him as Lamborghini’s first Technical Director in 1963. Dallara was responsible for the Miura’s rear-wheel drive and transverse mid-engine layout, which set the scene for the Diablo’s own layout. When Dallara left in 1967, Ferruccio immediately asked Paolo Stanzani to take over as Lamborghini’s next Technical Director. Stanzani was a true genius who realised that a longitudinal mid-engine layout, as he adopted for the Countach, held many advantages and the Diablo religiously followed the Countach with a longitudinally oriented V12 engine. But Stanzani’s real engineering brilliance was shown in the conception, design and delivery to production of the Countach’s revolutionary south-north engine-gearbox orientation. Here again, the Diablo obediently followed the Countach’s novel design. And why not? It was a supremely elegant engineering solution, which would also be adopted for the Murciélago and Aventador. It was also Ferruccio Lamborghini who brought in Nuccio Bertone and Marcello Gandini, who in time would almost become Lamborghini’s in-house stylists. Gandini’s extreme wedge-shaped cars, and his jaw-dropping guillotine doors, would go on to influence a generation and a half of supercar design, including the Diablo.

No comprehensive story about the Lamborghini Diablo would be complete without examining Ferruccio Lamborghini’s own history, the life experiences that moulded him and guided his business decisions, simply because without him there would never have been a Lamborghini supercar manufacturer, let alone a Lamborghini Diablo supercar.

The period after Ferruccio Lamborghini was forced to sell his car company should also be examined as this was a particularly turbulent time for Sant’Agata, with multiple changes of ownership, lawsuits, receivership and creditors constantly at the door asking for cash. This was the world in which the Lamborghini Diablo was conceived, developed, manufactured and marketed, and the Diablo was the child of all this chaos and uncertainty.

FERRUCCIO LAMBORGHINI

Ferruccio Lamborghini’s distaste for racing cars and motor sport only extended as far as the involvement of his own supercar company. As a young man he was a keen amateur racer, who designed and built racing car parts, and even extensively modified a whole car. While still in his early thirties, and at a time when he was not yet a rich man, he nevertheless indulged his craving for motor sport by taking part in the Mille Miglia. His reluctance to get Lamborghini SpA involved with racing stemmed from sheer pragmatism, and to understand the origins of this hard-headed, unsentimental rationality we will need to examine his childhood and early adult life.

Lamborghini was born on 28 April 1916. His birth sign, Taurus, became the emblem of Automobili Lamborghini S.p.A.

Ferruccio Elio Arturo Lamborghini was born on 28 April 1916 into a family of canepa (hemp) and fruit farmers. His forefathers had cultivated their land in Renazzo, a village in the commune of Cento, for generations. Renazzo lies about 24 kilometres north of Bologna, and his parents Antonio and Evelina earned a comfortable if not luxurious living from their labours off this ancestral land. From an early age Antonio and Evelina taught Ferruccio the vital importance of hard work, but he was also brought up within the unforgiving environment of farming, where luck in terms of the weather and plant disease was equally as important to success as hard work. Ferruccio quickly learned to make his own luck.

Seen across what would have been the Lamborghini family’s hemp fields and fruit orchards in 1916, the red house is where Ferruccio Lamborghini was born. His early mechanical exploits were carried out in an adjacent barn, which he burned down in the course of one of his technical experiments.

Antonio and Evelina quite reasonably expected Ferruccio to follow in their footsteps and become an agricultural farmer. But he was fascinated by machinery, and while still a child persuaded his parents to give him some space within one of their barns to set up a small machine shop. This was one of the earliest recorded instances of Ferruccio making his own luck by enthusiastically and aggressively pursuing what he wanted, rather than simply following the path that was expected of him. His fabled battle with Enzo Ferrari was a later example of this same dogged fighting spirit, wherein he decided to enter into direct competition with Ferrari rather than meekly tolerate the abuse that the patrician Enzo felt he could direct at a simple Emilian farm boy.

Through hard work and an instinctive feel for mechanical components and basic engineering principles, the young Ferruccio was soon modifying and improving his parents’ farm machinery. Not every task went exactly to plan though, and on at least one occasion Ferruccio set his workshop alight! His parents recognised Ferruccio’s love and aptitude for engineering, and, being modestly well-to-do, were able to support his ambition to become an engineer. They paid for his education at the Fratelli Taddia Technical Institute where he studied engineering and industrial design.

Lamborghini made his first fortune from lightweight tractors known as carioche.

Ferruccio Lamborghini turned global disaster into personal luck with World War II. In many ways this was the making of his personal and professional life. Ferruccio enrolled in the Italian Infantry (and not, as his son Tonino Lamborghini patiently explained to the authors during one of several interviews, the Regia Aeronautica, as is so commonly misstated in many publications) and was sent to the island of Rhodes. There he started as a junior mechanic with the rank of Caporale in the 50th Autoreparto Misto di Manovra. Again his enthusiasm and aptitude soon gained his promotion to Head of the Workshop Division, but Ferruccio also made his own luck by getting to know and earning the trust of the base’s commanding officer by expertly servicing and modifying the commander’s beloved red Alfa Romeo 1750. But as with the burnt-out barn back home, not every modification went smoothly. Ferruccio conducted a ‘modification and improvement’ exercise on the Alfa Romeo’s braking system that failed spectacularly while the commander was driving along one of Rhodes’s coastal roads. The 1750 ended up in the Mediterranean, but the commander forgave the very likeable Ferruccio.

In 1944 the British overran Rhodes. Ferruccio was taken prisoner and put to work servicing and repairing British army vehicles. During this time, when he met his future wife Clelia Monti, he also gained experience and insight into the workings of British engines. This knowledge would turn out to be instrumental in his future success when building tractors.

On his return to Renazzo in 1946 Ferruccio found that mainland Italy’s industrial base had been devastated by the war, and that Italian farmers throughout the country were desperate for tractors. His wife Clelia, sadly, had died shortly after giving birth to their first child, Antonio (Tonino) Lamborghini. Soon after, however, Ferruccio married his second wife, Annita Borgatti, and it was during their honeymoon in Romagna that Ferruccio happened upon a discovery that would change his life. He heard that the British military were selling off their surplus war equipment, and he bought a 4-cylinder Morris truck from the occupying force. He drove the truck back to Renazzo and converted its 1548cc petrol engine to run on Italian agricultural fuel, which was then both cheaper and more readily available. With further modifications, Ferruccio then made his first carioca, a lightweight tractor that would soon gain immense popularity in post-war Italy.

Ferruccio made more of his own luck by choosing to launch his new tractor in the town of Cento, the region’s agricultural centre, on 3 February 1948, which happened to be the feast day of St Blaise (Biagio in Italian), Cento’s patron saint. On this one day all the region’s usually hard-working farmers would be partying late into the night in Cento’s central piazza, and Ferruccio astutely parked one of his new cariocas nearby. By the end of Cento’s San Biagio festivities, Ferruccio had secured eleven orders for his new carioche (as they became known in Emilia-Romagna).

This was just the start of a very successful period for Ferruccio. By the end of 1948 he had garnered so many orders for carioche that he set up a purpose-built tractor factory in Pieve, not far from Renazzo. By 1952 he was manufacturing all new tractors of his own design, and by 1954 he was building air-cooled diesel tractors. By the early 1960s about 5,000 tractors were being produced every year under the Lamborghini Trattori banner.

In 1960 Ferruccio Lamborghini visited the United States as part of an Italian trade delegation. He was hugely impressed by what he saw happening across the Atlantic, and on his return to Italy decided to enlarge and diversify his already massive industrial empire. He founded Lamborghini Bruciatori to manufacture domestic and industrial air-conditioning and heating equipment.

Part of Lamborghini Bruciatori’s almost immediate success was due to Ferruccio following the same sales, marketing and after-sales protocol that he had established for Lamborghini Trattori. Central to this strategy was his novel approach to customer care, establishing in-house quality control protocols that were strictly adhered to, and his companies were among the first in Italy to offer comprehensive after-sales service plans for their products. Ferruccio’s supercar company would later follow this same customer-oriented doctrine. He said that he wanted to produce only the finest cars, and that he wanted his customers to be delighted with their vehicles. It didn’t always turn out this way, but that was his stated intention. By the time he was in his mid-forties he was one of Italy’s key industrialists and a very rich man.

Ferruccio had always had a passion for motor cars and motor racing. As a young man he modified an old Fiat 500 Topolino and entered it into the 1948 Mille Miglia. The Topolino’s 569cc engine was bored out to 750cc, and Ferruccio cast his own cylinder head out of bronze to squeeze as much power and torque as possible out of this still minuscule engine. His Topolino would have to compete with purpose-built 6- and 12-cylinder giants from the likes of Alfa Romeo, Ferrari and Maserati on the Mille Miglia’s tortuous 1,000-mile, figure-of-eight public road circuit between Brescia and Rome and back. For the first 700 miles (1,126km) Ferruccio did well, but he lost control of his car when passing through the commune of Fiano at speed and crashed into a roadside restaurant. Later he would often quip: ‘I finished my Mille Miglia in an osteria, which I entered by driving through a wall.’

Lamborghini made his second fortune through heating and air-conditioning machinery.

Ferruccio’s passion for motor sport and racing cars cooled following his Mille Miglia accident, but not his infatuation with road cars. His considerable wealth allowed him almost unlimited licence to indulge in this craving, and his fleet included cars from Mercedes, Mustang, Buick and Maserati.

By the early 1960s Ferrari had established a reputation that transcended motor sport. Its road cars were commonly acknowledged as some of the fastest, most beautiful and most prestigious available. Naturally these very special cars would soon come to Ferruccio’s attention: he bought a white two-seater Ferrari 250 GT short-wheelbase Berlinetta in 1958, and then another, and later a grey 2+2 Ferrari 250 GTE. Contrary to common belief, Tonino Lamborghini emphasised to the authors during an interview in 2019 that his father loved his Ferraris. Ferruccio was very impressed by the quality of their design and engineering, particularly their ‘perfect balance, and the strong engine that went very well’. Tonino stressed that his father’s only complaint about his Ferraris related to their clutches.

Again there is a popular belief that Ferruccio Lamborghini’s battle with Enzo Ferrari over clutch wear was the sole factor that led him to establish his eponymous supercar company. This is almost certainly an over-simplification of the myriad of considerations that probably led to the establishment of Automobili Lamborghini SpA, but it was certainly a very important factor.

Ferruccio was a proud man: not at all arrogant, but proud, open and honest about his humble beginnings and how far he had come through hard work, and he hated the disdain with which Enzo Ferrari treated him.

The infamous Lamborghini-Ferrari fight was a long time coming. Ferruccio used all his cars hard, extracting the most from their acceleration, braking and cornering potential, driving them in this extreme manner more frequently than the average supercar customer might. Time and again he found that the clutches of his Ferraris would slip under hard acceleration, even immediately after a brand new clutch replacement. After a few visits to the Ferrari works at Maranello, none of which permanently resolved this clutch problem, Ferruccio decided to look into the matter himself. With the help of one of his tractor mechanics, he stripped down a Ferrari clutch mechanism and discovered that the clutch plate was too small in diameter to cope with the engine’s torque output. The problem was cured by replacing the Ferrari’s original clutch with a larger diameter clutch from one of his tractors.

Having found a solution to this previously apparently unsolvable problem, Ferruccio decided that it would be in everyone’s interest to inform Enzo Ferrari about the primary cause of the clutch issue and how it could easily be resolved. Ferruccio was a very straightforward character, maybe blunt to a fault, but never one to bear malice. Tonino explained that Ferruccio approached Enzo politely and in good faith.

The Commendatore was, however, cut from quite different cloth. As a way of keeping people in their place, Enzo was known to intentionally make customers and guests wait for long periods in an ante-room before granting them an audience – and he kept Ferruccio waiting for hours after the appointed time before receiving him. When Ferruccio complained about this delay, Enzo’s reply was ‘One day I kept the King of Belgium waiting, so you Mr Lamborghini, builders of tractors and boilers, really have no cause for complaint.’ From then their conversation took a progressively downward trajectory. When Ferruccio complained about the clutch and politely explained his new-found solution, the Commendatore became furious and said, ‘Lamborghini, you may be able to drive a tractor, but you will never be able to drive a Ferrari properly.’

According to Ferruccio Lamborghini, it was this singularly venomous statement, said aloud at their meeting, that ignited his momentous decision to set up a rival supercar company. Ferruccio has been widely quoted as saying, ‘This was the point when I finally decided to make a perfect car.’

AUTOMOBILI LAMBORGHINI SpA

It is highly unlikely, however, that the shrewd, worldly-wise and financially astute Ferruccio Lamborghini would have committed to such a major undertaking solely after an insult from someone he barely knew. Rather there were almost certainly other major factors at play. By the early 1960s Ferruccio had more money than he knew what to do with. What he wanted now was power and recognition. Establishing a bespoke supercar company catering to the world’s most exclusive clientele, and directly entering battle with Ferrari at Maranello, was surely the fastest way of grabbing everyone’s attention, particularly in car-mad Italy. Another reason for setting up Automobili Lamborghini SpA was to diversify his industrial empire. From his work on his tractor and heating and air-conditioning businesses, he already knew exactly how to work his way around Italian government legislation and how to exploit generous government subsidies, so this new venture promised lucrative gains for relatively little effort and risk. Thirdly, a Ferrari-rivalling supercar would garner wide and positive publicity for the Lamborghini name, and this reflected glory would bestow much welcome publicity upon his tractor, heating and air-conditioning businesses. And finally, of course, he was a genuine petrolhead who had been an engineer and mechanic at heart from childhood.

Not one to procrastinate, Ferruccio bought 9 hectares of land on the outskirts of Sant’Agata Bolognese in 1962. This was an inspired choice of location because it was close to Modena, from which Ferruccio could recruit specialist workers skilled in engineering, manufacturing and tooling, and also because Sant’Agata had excellent transport links through which raw materials could be brought in efficiently, and gleaming supercars could be shipped out effortlessly. The two-flavoured icing on the cake was that the local council was offering concessions and grants to attract new businesses to the region, and additionally Sant’Agata was close to Cento, where the Lamborghini tractor, heating and air-conditioning factories were already established.

By the middle of 1963 Ferruccio had established Automobili Lamborghini SpA and had spent 500 million lire on the first phase of the factory build. At that time this was a vast amount of money for a small car factory, but Ferruccio was determined that his new plant should be outstanding in itself, and not just for the products that came out of it. It was a well thought-through and modern factory, with half a million square feet of factory floor space housed within two long buildings, and it featured a twin-track production line, a spare parts repository and a service department. The factory boasted a very futuristic feel with natural sunlight flooding onto the production line from large galleried windows, and there was of course the now famous terracotta tiled flooring. Clerical staff were based in offices on the first floor of the buildings, a service road encircled the whole factory perimeter, and the word Lamborghini stood out proudly in bright yellow lettering from the top of the factory roof. Despite the many substantial factory renovations that have taken place since 1963, some of these original features can still be seen today, and many were present in an unaltered form when the authors visited the factory at the end of the Diablo’s production run in 2001.

The lead author with Automobili Lamborghini’s first car, the concept 350GTV, at the factory museum in Sant’Agata Bolognese.

When Ferruccio Lamborghini launched his first prototype, the Lamborghini 350 GTV, on 20 October 1963, the invited motoring journalists, potential customers and high-ranking government guests were as stunned by the cutting-edge factory as they were by his avant-garde prototype supercar. He had just won one of the prizes he most coveted – recognition. At first this recognition was limited to local dignitaries, petrolheads and the specialist motoring press, but with the launch of the Lamborghini Miura in 1966 the wider motoring world would come to recognise that they had a genuine Ferrari-beater in Lamborghini. The launch of the Lamborghini Countach prototype in 1971 brought instant worldwide fame and recognition from all those who swooned in automotive lust at Ferruccio’s wedge-shaped, guillotine-doored, wonder car. The Lamborghini Diablo would continue in this tradition – sprinkling the fairy dust of expensive, elusive and much-wanted publicity on the Lamborghini name and all its associated brands and products. Ferruccio had succeeded in his second aim too.

Making a success of Automobili Lamborghini SpA as a self-financing business, however, would prove to be greatest of the three challenges. Base raw materials flowed into one end of Lamborghini’s Sant’Agata factory and, through some glorious alchemy, the most astounding and extraordinary cars came out of the other. The Lamborghini 350 GT, 400 GT, Jarama, Espada, Miura and Countach were usually in high demand by very well-heeled customers worldwide, but this was not always the case and keeping the balance sheet in the black during bleak recessions and lesser economic downturns would plague Automobili Lamborghini SpA throughout its early history. The Lamborghini Diablo’s conception, birth and development would almost be defined by the company’s financial fortunes and misfortunes.

The company banner flutters at the entrance to the Sant’Agata factory.

The high point of Ferruccio Lamborghini’s involvement with supercar manufacture probably came with the Miura. The company gained instant and widespread recognition through this revolutionary supercar, and it was also in rude financial health at this time. In 1966 Ferruccio’s industrial empire employed about 4,500 people and he was one of Italy’s most important industrialists. He was awarded the title of Commendatore Ordine al Meritodella Repubblica Italiana for his services to Italian manufacturing, and later in 1969 was awarded the further honour of Cavaliere del Lavaro.

But industrial unrest was just round the corner. Strike action began in earnest in 1970. The seeds of this unrest had actually begun with students staging protests about the cost of living and university fees in 1967, and trade unionists started agitating about pay and employment terms and conditions in 1968. When the students joined forces with the more militant trade unionists the touchpaper was lit for crippling economic chaos. By 1973 more than 6 million Italians were on strike, and all industrialists were seen as exploitative mega-capitalists who should be treated as social pariahs. Ferruccio had never forgotten his roots, had never knowingly abused any of his workers, and was in fact recognised as a very considerate boss who was ever ready to roll up his sleeves and crawl underneath a faulty tractor or a misbehaving supercar. He was very upset at being cast as an unscrupulous and uncaring plutocrat, and his misgivings about business began at this time, which also coincided with the Countach prototype’s debut. The additional fame that the Countach brought Ferruccio was therefore something that he both desired but also eschewed. In happier times he would merely have bathed in all the exaltation. Any unhappiness was further fired up when his own workers, with whom he had previously had an excellent relationship, also became more bellicose and militant purely through osmosis.

LOSING CONTROL

The killer blow came in 1972 when the Bolivian government cancelled an order for tractors. This hit was intensified by the 1973 oil crisis and the subsequent 1973–4 stock market crash. The Bolivian government had previously placed an order for 5,000 tractors in good faith, and in equally good faith Lamborghini Trattori had sourced the necessary materials and built these tractors without taking a deposit or any other form of pre-payment. In 1972 political and economic turmoil in Bolivia sent shock waves far and wide, including to Emilia-Romagna in Italy. The Bolivian government’s abrupt cancellation of their tractor order came with no financial compensation, and Ferruccio was left with a serious cashflow problem. He managed to get through this sudden downturn by selling off some of his tractor factory buildings to Giovanni Agnelli, the ‘Godfather of Fiat’, at well below market value. At Agnelli’s insistence, an unwilling Ferruccio also had to transfer some of his best tractor factory staff onto Fiat’s payroll. When this proved insufficient to keep his creditors at bay, he sold 51 per cent of Lamborghini Trattori to the giant Italian tractor company S.A.M.E., which had been pursuing Ferruccio for years in the hope of buying into Lamborghini Trattori and thereby gaining a seat on the board of the Emilian tractor company. The Bolivian debacle gave them just the opportunity they had been looking for.

The impact of the Yom Kippur war extended as far as Sant’Agata. In October 1973 the Organisation of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) imposed an oil embargo on all those countries they deemed supportive of Israel. This embargo lasted until March 1974 and during this time the price of oil quadrupled, resulting in petrol rationing in some countries, the introduction of stringently monitored and fiercely enforced speed limits, and societal rejection of gas guzzlers. None of this advanced Sant’Agata’s cause, or indeed that of any other company producing 170mph, petrol-thirsty supercars. When both the New York and London Stock Exchanges dived in 1973 it was the start of a global recession that impacted exactly the sort of potential Lamborghini customers who otherwise would have had the financial wherewithal to indulge their supercar cravings. And meanwhile the union-led industrial problems were continuing apace.

The 1972 Bolivian tractor debacle soon forced Ferruccio to sell 51 per cent of Automobili Lamborghini SpA to the Swiss businessman Georges-Henri Rossetti. The completion of this quick and involuntary sale was necessary simply to keep the company afloat. A more considered sale of his remaining 49 per cent stake in Automobili Lamborghini SpA to René Leimer, one of Rossetti’s many business associates, took place over the following eighteen months. This came about partly because Ferruccio was tired and traumatised by the never-ending ups and downs of his business empire, and partly because he was reluctant to give in to the combative, constantly demanding and never happy trade unionists in his supercar factory. A further factor was that he recognised that society’s new environmental, safety and social concerns would make it ever more difficult to sell extravagant, very high-speed, highly polluting, bespoke supercars.

In 1974, having divested himself of any further involvement with Automobili Lamborghini SpA, Ferruccio Lamborghini retired to La Fiorita, a 32-hectare vineyard near Lake Trasimeno in Umbria. He lived out the rest of his days on this estate, actively participating in his new wine business surrounded by his beloved Sangiovese, Merlot, Gamay and Ciliegiolo vines. One of the most famous wines his vineyard produced was officially called ‘Colli del Trasimeno’, but unofficially this outstanding red wine was called ‘Sangue di Miura’ (Miura’s blood). This final stage of Ferruccio’s life was peaceful and happy. He passed away on 20 February 1993 after an unexpected heart attack, and his body was taken back to Renazzo where it was interred alongside those of his ancestors.

La Fiorita, the Umbrian vineyard where Ferruccio spent his last days.

Ferruccio Lamborghini’s fingerprints are all over every Diablo ever produced, although he had officially left the supercar company a full decade and a half before the Diablo made its debut, and even though the Diablo was barely a fifth of its way through its production life cycle when Ferruccio drew his last breath. Sant’Agata’s recognition of his contribution to the Diablo was most tellingly demonstrated when one of the earliest Diablo pre-production prototypes was sent across the Apennines from the factory to La Fiorita, just to get Ferruccio’s blessing for Automobili Lamborghini’s latest flagship car. The authors visited La Fiorita in 2018 and were lucky enough to meet and interview Ferruccio’s long-standing secretary from this period, Giuseppina Maccioni. Signora Maccioni said that Ferruccio was delighted that Sant’Agata had remembered him, and recollected the Diablo’s arrival at La Fiorita. In the peace of his vineyard Ferruccio had inspected the Diablo closely and at leisure. His considered verdict on the Lamborghini Diablo: ‘A true Lamborghini’.

FERRUCCIO’S HEIRS

The stewardship of Automobili Lamborghini SpA by Georges-Henri Rossetti and René Leimer makes for a sorry story. They were very hands-off owners with little interest in their new acquisition, and even less understanding of the complexities of supercar manufacturing. They hardly ever visited Sant’Agata, abdicating almost all responsibility for the running of the business to the factory managers. The Countach almost single-handedly kept the company afloat during their tenure as sales of the Espada, Jarama and Urraco during this period were thoroughly underwhelming. Combative trade union policies and practices made running the factory efficiently very difficult, and this was compounded by the continuing fallout from the oil crisis and the stock market crash, both of which were adversely affecting the global economy. Chronic poor management might have been the primary factor that drove the company to the wall, but it was an acute cashflow problem that rang the death knell for Rossetti’s and Leimer’s ownership.

In August 1978, after essentially running out of money, the company went before the Italian courts. Judge Mirone, who was well disposed to the company and Italian industry, astutely placed Automobili Lamborghini SpA under the control of Alessandro Artese, a shrewd and insightful accountant. He in turn appointed Giulio Alfieri, the acclaimed ex-Maserati engineer, as Technical Director, and retained the experienced and industrious Ubaldo Sgarzi as Sales Director. This triumvirate provided new dynamism and direction for the company, and they almost succeeded in finding a new owner for Automobili Lamborghini SpA Sadly, at the very last moment, a conglomerate headed up by Hubert Hahne was unable to secure the money needed to buy the company. A huge amount of work and hope had gone into this potential sale and both parties were deeply disappointed when the deal fell through. Worse was to follow: on 28 February 1980 Automobili Lamborghini SpA was declared bankrupt and placed into receivership.

In July 1980 two French brothers, Patrick and Jean-Claude Mimran, took over management of the company and renamed it Nuova Automobili Ferruccio Lamborghini SpA. Heirs to a vast industrial empire stretching across most of the globe and encompassing a multitude of industries, the Mimrans were superbly well placed to run the company. Patrick Mimran in particular was a genuine car and Lamborghini enthusiast, and both brothers were young, energetic and enthusiastic. They revamped the company’s management structure with Patrick Mimran becoming Chairman, Emile Novaro his immediate abettor, Alfieri promoted to Technical Director-cum-General Manager and Sgarzi retained as Sales and Marketing Director. In May 1981, happy with the growth and improvement they had been able to inject into the company, the Mimrans bought Nuova Automobili Ferruccio Lamborghini SpA outright. They paid 3,850 million lire for the company (about US$3 million). Patrick Mimran was quickly able to establish his new acquisition on a genuinely solid financial footing, and he was also instrumental in providing the direction and funding for the Countach’s further development. The Countach LP 400 was still in production when Patrick Mimran took over the company, but over the course of his tenure at Nuova Automobili Ferruccio Lamborghini SpA the company developed and produced the Countach LP 400 S, the Countach LP 500 S, the Countach 5000 QV and laid the groundwork for the 88 1/2 Countach 5000 QV. Patrick Mimran saved Automobili Lamborghini from oblivion and successfully re-established the company as one of the world’s foremost supercar manufacturers, an astounding achievement bearing in mind that he was barely twenty-four years old when he took over the management in 1980. The Mimran brothers sold Nuova Automobili Ferruccio Lamborghini SpA to the Chrysler Corporation in 1987. Chrysler paid US$25 million for their trophy Italian supercar company, thereby netting the Mimrans a very healthy profit.

Giampaolo Dallara, Lamborghini’s first Technical Director, examines a copy of Crowood Press’s Lamborghini Countach:The Complete Story and a photograph of 5000 QV F920OYR (seeChapter 14).

Lamborghini’s successor flagship to the Countach was first mooted in the Mimran era, but the Diablo only came to market in 1990 under Chrysler. Chrysler, and in particular its chairman Lee Iacocca, had been looking to buy into, or preferably buy outright, a high-profile, top-drawer supercar manufacturer with which to crown and hopefully lift up Chrysler’s rather utilitarian image. Chrysler’s market was largely based in North America and catered to a mainly down-to-earth clientele. What better way to sprinkle a pinch of fairy dust upon Chrysler, than to have a bespoke, ultra high-performance, European subsidiary within Chrysler’s portfolio. As Lee Iacocca was of Italian ancestry, and very partial to his heritage and culture, an Italian supercar manufacturer was the ideal candidate. Iacocca started off by buying a 15 per cent share in Maserati, but no Maserati could compare with the contemporary Lamborghini Countach 5000 QV. In fact nothing in series production by any manufacturer on the planet could remotely compare with this latest Countach. By a happy coincidence the Mimrans were looking to sell just when Iacocca was looking to buy. Patrick Mimran had invested money, time and some of his soul into Nuova Automobili Ferruccio Lamborghini SpA and he was determined only to sell the company to someone, or to some entity, that would cherish, nurture and advance it. In Lee Iacocca he saw someone genuinely keen on Sant’Agata, and in Chrysler he saw a major player with the financial wherewithal and the business acumen to take the company forwards.

Chrysler invested heavily into Lamborghini, providing not only money but also technical resources. The 88 1/2 Countach 5000 Quattrovalvole was said to be built to a higher standard than any of its predecessors purely because the factory workers now had all the exact parts they needed: prior to Chrysler’s takeover they often had to modify whatever parts they needed from whatever was then available in the parts bin. Chrysler also helped by insisting on more stringent build and quality control than Sant’Agata had ever previously judged necessary.

Tonino Lamborghini, Ferruccio Lamborghini’s son, expands on the family’s long association with farming, tractors and supercars.

If the Countach’s replacement had originally been conceived under the Mimran administration, it was under Chrysler that the Diablo was gestated, developed, refined and finally launched in 1990, as will be described in detail in the following chapters. Suffice it to say here that the Diablo was received with great acclaim by potential customers, the motoring press and the general public alike. The order book filled up almost immediately, and a long waiting list full of customers hungry for Lamborghini’s latest flagship soon developed. For once Lamborghini was destined for that rarest of treats – it was going to make a profit. The Sant’Agata engineers and designers, the Chrysler accountants and Lee Iacocca were all delighted, and the latter two parties felt totally vindicated in their decision to cross the Atlantic and buy a tiny, almost loss-making car manufacturer. But as so often in Lamborghini’s history these halcyon days were short-lived. Rising inflation caused the world’s major central banks to raise interest rates and enact restrictive monetary policies that, combined with the 1990 oil price shock, pushed the West into recession. Existing Diablo orders were cancelled and new orders simply never materialised. Soon Lamborghini was back to its hitherto normal state of making losses and Chrysler’s love affair with Sant’Agata went cold. By 1992 Chrysler quietly made it known that it wanted to offload its now tarnished Italian jewel.