21,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

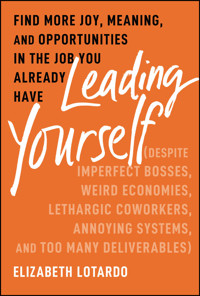

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

Create the work experience you want in the less-than-perfect job you already have.

In Leading Yourself, celebrated workplace thought leader Elizabeth Lotardo delivers an engaging guide to owning and elevating your work experience. With tips, watchouts, and funny stories, Leading Yourself will give you the encouragement and tactics to up-level your career, even if you aren't in your dream job. You'll learn to manage your self-talk, find meaning in the mundane, optimize your time at work, and build relationships with the people who matter.

Lotardo, a wildly popular LinkedIn Learning Instructor, shares key behaviors and habits that will transform the way you experience your job and unlock opportunities for career growth. You'll discover:

- Strategies to overcome self-doubt, embrace change, and navigate uncertainty

- Talk tracks for handling difficult bosses, like micromanagers, know-it-alls, and leaders who constantly change their mind

- How to avoid the awkwardness of giving and receiving feedback and what to do when the feedback is wrong

- Tips for preserving your own reputation when other people don't deliver (or if your company majorly messes up)

- Frameworks for evaluating and making your next career move

Leading Yourself puts the power back in your hands. Even if you work for a fallible boss or imperfect organization, you can change the way you experience your job. An indispensable guide to self-leadership for aspiring and current managers, executives, directors, and other business leaders, Leading Yourself is the roadmap you've been waiting for.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 326

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

Why I Wrote This Book

Defining Your End Game

What We Want Out of Work

What We Hate About Work

What If …

Part I: Mindset: Managing the Space Between Your Ears

Chapter 1: Finding Purpose in a Normal Job

The Purpose Backstory

You're More Than Your Job

It's OK If You're Not Passionate

Purpose and Our Health

Purpose Creates Performance

When Your Company Has a “Purpose” But You Don't Feel It

How to Find Your Purpose (Amongst Your Deliverables)

There's No Guarantee

Chapter 2: You See What You Look For

“Nobody Wants to Work Anymore” and Other Workplace Lies

Dissolving Your Own Load‐Bearing Neural Pathways

Adding Support Beams

The Risk of Toxic Positivity

When It (Inevitably) Still Goes to Shit

Chapter 3: Quiet Fear

The Upside

Deciding When to Go for It

Own Your Potential

Chapter 4: Embrace Change and Uncertainty

This Is Your Chance

Lose Your Attachment to Sunk Costs

Avoiding the Ick of “Startup Culture”

Don't Wait for Everything to Be “Settled”

Part II: Behavior: Showing Up as Your Best Self (Most of the Time)

Chapter 5: Hit Goals with Momentum

The Overpromising Trap

Why Performance Reviews Result in Mediocre Goals

Good‐Enough Goals (That Your Manager Will Approve Of)

If (When) You Fall Short

The Magic Is in the Pursuit

Chapter 6: Don't Look for Energy – Create It

Your Boss Doesn't Care About Your Enneagram

Start Where It Feels Fun

Work from Where?

Enduring Things (or People) Who Make You Tired

Give Your Brain the Learning Fuel It Craves

Chapter 7: Know When to Phone It In

Be Invaluable, Not Indispensable

Choosing What Matters and What Doesn't

Nobody Is Going to Bleed Out on the Table

Beyond Your 9 to 5

Overcoming the Mental Hurdle

Part III: Working with Other People (Even Annoying Ones)

Chapter 8: Boss Management

Your Boss Is Not Your Servant (and You Aren't Theirs, Either)

Beyond Status Updates: Making Your 1‐1 Impactful

Surviving Your Boss's (Annoying) Idiosyncrasies

They're (Probably) Not Doing It On Purpose

How to

Temporarily

Work for an Asshole

Making the Most of an OK‐Enough Boss

Chapter 9: Disagree and Commit

Trust the Experts

Disagree and Commit in Action

Appeasing the Illusive Corporate Overlords

Determining Your Hill to Die On

You Always Get to Decide One Thing: Your Response

Chapter 10: Feedback Without the Awkwardness

Asking for Feedback: A Lesson from Cartoonists

A Clear Ask

The Feedback Behind the Feedback

Assess, Don't Obsess

Don't Make Other People Pay the Price for Your Discomfort

Chapter 11: All Those Other People

The Misery of Unmet Expectations

Safeguarding Yourself Against Negativity

Friends at Work

Dealing with Lazy Ants

Who Is the Common Denominator?

Giving the Benefit of the Doubt (Even to People Who Seemingly Don't Deserve It)

Chapter 12: Your Next Play

Don't Linger Too Long

Honing in on Your Superpower

Networking (Ugh)

Don't Burn Bridges … Except in These Three Situations

When It Doesn't Go According to Plan

When It

Does

Go According to Plan … and Still Feels Bad

Listening to Your Gut When Your Gut Has Anxiety

Conclusion

Notes

Introduction

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Illustrations

Chapter 1

Figure 1.1 Ikigai representation.

Figure 1.2 Passion versus purpose.

Figure 1.3 Purpose cycle.

Figure 1.4 Lack of purpose cycle.

Figure 1.5 Impact map template.

Figure 1.6 Example impact map.

Chapter 2

Figure 2.1 Belief cycle.

Figure 2.2 Counter thoughts.

Figure 2.3 Annoying, garbage, or abuse.

Chapter 3

Figure 3.1 Board presentation risk versus reward.

Figure 3.2 New idea risk versus reward.

Figure 3.3 Tough feedback risk versus reward.

Chapter 4

Figure 4.1 This is my chance examples.

Chapter 5

Figure 5.1 Four burner theory.

Figure 5.2 Hockey stick projection.

Figure 5.3 Output to input goal shift.

Chapter 6

Figure 6.1 Learning mindset.

Chapter 7

Figure 7.1 Choosing what matters.

Chapter 8

Figure 8.1 Purpose‐driven leadership.

Figure 8.2 1‐1 Priorities.

Figure 8.3 Clarity and control boss challenges.

Chapter 9

Figure 9.1 Concrete cascade.

Figure 9.2 Intent and impact.

Chapter 10

Figure 10.1 Thought process feedback delivery.

Chapter 11

Figure 11.1 Negativity cycle.

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Begin Reading

Conclusion

Notes

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Index

End User License Agreement

Pages

iii

iv

v

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

13

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

123

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

223

224

225

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

Leading Yourself

FIND MORE JOY, MEANING, AND OPPORTUNITIES IN THE JOB YOU ALREADY HAVE (DESPITE IMPERFECT BOSSES, WEIRD ECONOMIES, LETHARGIC COWORKERS, ANNOYING SYSTEMS, AND TOO MANY DELIVERABLES)

ELIZABETH LOTARDO

Copyright © 2024 by McLeod & More Inc. All rights reserved.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per‐copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750‐8400, fax (978) 750‐4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748‐6011, fax (201) 748‐6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permission.

Trademarks: Wiley and the Wiley logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762‐2974, outside the United States at (317) 572‐3993 or fax (317) 572‐4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic formats. For more information about Wiley products, visit our website at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data:

Names: Lotardo, Elizabeth, author. | John Wiley & Sons, publisher.

Title: Leading yourself : find more joy, meaning, and opportunities in the job you already have / Elizabeth Lotardo.

Description: Hoboken, New Jersey : Wiley, [2024] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2024014708 (print) | LCCN 2024014709 (ebook) | ISBN 9781394238705 (hardback) | ISBN 9781394238729 (adobe pdf) | ISBN 9781394238712 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Career development. | Success in business.

Classification: LCC HF5381 .L666 2024 (print) | LCC HF5381 (ebook) | DDC 650.1—dc23/eng/20240506

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2024014708

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2024014709

Cover Design: Paul McCarthy

To my son … you are never powerless.

Introduction

“I don't like to gamble, but if there's one thing I'm willing to bet on, it's myself.”

—Beyoncé

I was never more optimistic and excited about the working world than I was before I entered it.

The month before I graduated from college, I was hanging out in a bar with a group of friends. We were sharing updates about what we'd be doing after graduation.

During school, I had waitressed, tutored, and nannied, but now, I was about to set out on my first full‐time professional gig. I gushed to my friends about the amazing job I had gotten as an Account Manager at an ad agency.

Most of my friends were equally enthused to be embarking on their “grown‐up” careers. One was starting work as a teacher, and another was an entry‐level engineer. Two had jobs selling software, one was going into consulting. Our eyes were wide and we felt ready to take on the exciting opportunities ahead. We were finally adults (or at least, that's what we thought).

Flash‐forward 10 months later; we got together again, at the same bar, even sitting in the same corner booth. Yet, the energy was drastically different. Most of us felt jaded, some even defeated. Only a few in the group were holding on to the enthusiasm we all had less than a year ago.

It was discouraging, to say the least. Perhaps you've experienced similar disillusionment yourself.

You apply for what seems like a great job, you eagerly prep for the interview, and you make sure all your references are in order. You ooze enthusiasm during the interview process. When you first get the offer, you're elated. You call your partner, your parents, or your friends, gushing about how excited you are to take this next step.

Then somehow, a year or so later, your dream job becomes the very job you're dreading on Monday morning. The projects you were excited about don't feel as inspiring anymore. The changes you wanted to make seem laborious instead of empowering. And the coworkers who once seemed so awesome are now a little bit annoying.

You may have assumed that I was one of the few 20‐somethings at the bar that night who still felt a zest for careerhood. Sadly, I wasn't. Less than seven months into the job I was once thrilled to get, I felt totally empty.

Yet, this all‐too‐common career comedown didn't happen to all of us sitting there in the booth. Just most of us. Three members of the group were still just as excited as they had been before we started our jobs. The rest of us assumed those three got lucky. They probably had better offices, better bosses, or more opportunities at work.

Spoiler: They didn't get lucky. In fact, one still‐ambitious, optimistic changemaker had the exact same job at the same company as another friend who was currently miserable.

In hindsight, I now see that those three people were leading themselves. They had shifted, from waiting to creating, from reactive to proactive, and from powerless to powerful, all within the constraints of a normal corporate job.

While the majority of us were hoping meaning, joy, and opportunities would come out of our work experiences, they were willing it into existence.

At the time, I didn't know what they were doing differently. All I knew was that they seemed happier and more fulfilled than I was. It's funny how a single event sticks with you, and as time marches on, you find yourself unpacking it more deeply.

As I moved through my career, working with different organizations, I started noticing how crazy it is that people with the exact same job (and sometimes even the same boss) experience wildly different realities at work. Time and time again, I watched one person flourish in their job, while their counterpart in the same role was floundering.

In retrospect, that scene at the bar makes total sense. I was right, those three people were experiencing more meaning, joy, and opportunities than the rest of us. What I was wrong about was assuming that they got lucky.

Since that time, I've deepened my studies. I've unpacked why some people can thrive in imperfect conditions. Not just survive enough to not get fired, but actually experience fulfillment through the messiness. While others, in the same circumstances, feel uninspired, disengaged, and often, powerless.

Ten years after spotting the power of self‐leadership in that bar, and seven years after coining the phrase “leading yourself” on LinkedIn Learning, I now see clearly that leading yourself is the difference between being happy and successful at work versus being bored and miserable.

For some people, like my three special friends, leading yourself is innate. For most people, me included, it's not.

Leading yourself is both a philosophy and a skillset that many of us bar‐goers did learn, after several years of painstaking progress (at least in my case).

Over time, we all got better at self‐leadership, the thing that came so naturally to those special three. We adjusted our expectations of prefect, learned to control the controllable, and got really clear about what we wanted work to be.

No matter where you are, things probably aren't perfect right now. Maybe parts of your job suck, or your boss doesn't listen, or your industry is a little behind. Maybe this isn't your dream job, your coworkers aren't your best friends, and you don't see a clear path to anything beyond Friday. Maybe things are actually pretty good, but you can't shake the gnawing feeling that they could be better. This book is going to meet you where you are.

Instead of waiting for the perfect job, the perfect boss, or the perfect market conditions, you take the reins now. You can create the work experience you want in the job you already have.

Why I Wrote This Book

In my last decade of consulting, I've read a ton of business books. The vast majority of them fail to make any lasting impact for two reasons:

They're aimed at the C‐Suite

… of which 99% of people are not in. Most people have zero direct reports. They don't control the products their organizations sell, the systems they use, or the goals they set. That's not a bad thing, it just means pie‐in‐the‐sky projections about the future of business are generally unhelpful, especially if you're an individual contributor.

They're frighteningly abstract

… Business books are full of studies and theories that show the benefits of innovation, purpose, and kindness in the workplace. These are things we instinctively already know. Obviously, people have more ideas when they're not being bullied at work, and when someone cares about something, they try harder. You don't need a book to tell you that. What's generally lacking is what do you

DO

with that information, at your actual job.

This is a book about real‐life work, not theoretical musings from an executive think tank.

My goal is to give you the tools to help you navigate all the imperfections of the working world in a way that leaves you happier and more successful. This book is full of talk tracks, templates, and examples from people at normal jobs inside of normal companies.

We're going to cover things like:

What do you say to your micromanager on Monday morning? (

Chapter 8

)

What do you do when all the people on the project you're leading stop responding to your emails? (

Chapter 11

)

How do you keep yourself from going insane through another re‐org? (

Chapter 3

)

What do you do if your boss or organization sets unrealistic goals? (

Chapter 5

)

How do you prioritize when everything feels urgent? (

Chapter 6

)

How can you not be mad every day when you disagree with the direction your organization is taking? (

Chapter 9

)

Here's the tough truth: If you're frustrated with your organization, your job, your coworkers, or your boss, you're the one paying the price. Not them. You're the one who's not going to do your best work, you're the one who is going to wake up in a bad mood, and you're the one whose career will suffer.

Leading yourself is about controlling the controllable. It's owning, from whatever seat you're in, your work experience. Your mindset, how you show up, and the relationships you build are what you control. Nothing else. That truth can be defeating or empowering, depending on how you look at it.

The world of work is annoying sometimes, no matter where you work or who you work for, and it's up to you to navigate that in a way you're proud of.

Leading yourself can help you do that.

Defining Your End Game

Think about someone you know who loves their job. They're always talking with excitement about the projects they have coming up. They have a good relationship with their boss. They're optimistic about the future, instead of afraid of it.

These people often aren't in the C‐Suite. They don't work for the exclusively cool‐kid companies. They don't typically have prestigious educations, unlimited resources, or generational wealth. They have ordinary jobs, at ordinary companies.

Yet, their work experience is anything but ordinary. They find meaning at work, despite annoyances. They're joyful, despite bureaucracies, setbacks, and dear god, another “pivot.”

You might find them admirable. You also might find them annoying. For most of us, it's a little bit of both.

The people who love their job have created a work experience worth loving, and you can do the same. Maybe not today, but you can set the wheels in motion.

Let me be clear on what I mean when I say “the work experience you want.” You might not want to be the CEO. You might not even want to be a boss at all. The “ideal work experience” varies widely because people and their priorities vary widely.

Here are some examples of what the work experience you want could look like:

You get promoted within 12 months to a managerial role. After that, you climb the ladder even more, making your way to executive leadership before you're 40.

You stay in your current job. Over the coming year, the people on your team regard you as one of the best, most supportive colleagues they've ever worked with. Your network of goodwill is second to none.

You gain autonomy to invest your brain space in things that are most interesting to you. After seeing how dialed in and strategic you are, your boss develops incredible trust in you and mostly leaves you alone.

You make your job even more efficient and impactful, enabling you to work a four‐day workweek, turn your email off at 3 p.m., or take a month's hiatus each summer to be with your family.

Your expertise becomes so valuable that you're put in charge of the next cool innovation project. Eventually, you get an interview at a cool startup you've been stalking on LinkedIn.

Only you can define what you're after, and that will likely change over time. The mindsets, skills, and beliefs of leading yourself can help you bounce between potentially all of the above throughout your career.

Before we dive in, I'm going to be really candid. Privilege makes leading yourself a lot easier. Money, time, emotional support, physical health, a strong network … it helps. A lot. Not having to deal with microaggressions, biases, or downright prejudice is an intellectual and emotional freedom only a portion of the workforce experiences today.

I'm going to challenge us to run a dual path:

We're all responsible for creating a more diverse, equitable, and inclusive world of work. Each of us has a personal duty to leave our colleagues, our customers, and our organizations better than we found them.

At the same time, we're going to work with what we've got. That is not synonymous with tolerating injustice. It's acknowledging the very real inequities, while at the same time, charting our own way and creating the unique future we desire.

What We Want Out of Work

How often do you experience the feeling of joy at work? Is it after a good performance review, a lunch with your colleagues, or finally achieving inbox zero?

In a recent Harvard Business Review survey, nearly 90% of respondents said that they expect to experience a substantial degree of joy at work, yet only 37% report that such is their actual experience.1 Even for those who are experiencing a substantial degree of joy at work, there's always room for more.

Joy is connected to meaning; those who view their role as critical to the success of the team are much more likely to experience joy at work. Those who feel their talents are utilized effectively are even more so.

That's not surprising. When we feel like we're making a difference, we're more likely to feel joyful. Finding delight in something you view as a perfunctory waste of time is nearly impossible.

Joy and meaning are what we want today, but as humans, we often find our minds concocting the next play. The retention research bears that out. Seventy‐six percent of employees are looking for opportunities to expand their careers. Eighty‐six percent of employees say they'd switch jobs for one with more chances to grow.2

Most disgruntled work experience stems from a lack of (at least) one of these three crucial elements: Joy, meaning, or opportunities.

The mistake I, and so many of my peers, made, is assuming that you can't make those things yourself. Is it easier if all of that is present the moment you onboard? Yes, but the absence doesn't have to be permanent.

No career will be an end‐to‐end experience of joy, meaning, and opportunities. If it was, you would pay your boss and we'd call it Disneyland. Yet, with you in the driver's seat, joy, meaning, and opportunities can be more frequent.

What We Hate About Work

We watch shows about how dreary the office can be. The comic strip Dilbert ran in thousands of newspapers for 30 years. There was even a movie about three friends who conspired to murder their awful bosses. In humor, there's truth. Yes, work can be fulfilling, rewarding, highly profitable, and a worthy endeavor. It can also be really frustrating.

In all the interviews I've done for this book, the research I've pored over, and in my own experiences, there are clear themes. No matter the industry, no matter the size of the organization, and no matter how well‐intended everyone is, the inevitable woes arise.

Here are some of the most common grievances, in no particular order:

Imperfect bosses.

We've all heard the expression: people don't leave their jobs, they leave their managers. While it's typically more complicated than that, the expression highlights just how crucial a manager is in the satisfaction and performance of their teams. Even a great boss has their imperfect moments. In a survey of 3000 employees about what employees dislike most in a manager, incompetence, a lack of availability, and micromanagement were at the top of the list.

3

Weird economics.

Are we going into a recession? Will AI spike unemployment? Why is chicken so expensive? As of writing this, according to a survey by Wolters Kluwer Blue Chip Economic Indicators, there's a 50% chance of a recession in the next 12 months

4

… so, there's also a 50% chance there won't be a recession in the next 12 months. Not exactly reassuring in either direction.

Lethargic coworkers.

According to CNBC, 90% of Americans have a coworker who annoys them and 55% of people reported that they still get annoyed with their coworkers several times a week in a remote vs. in‐office environment.

5

One leader I spoke to said, “My actual job is easy, it's working with the other 748 people here that can be challenging.”

Annoying systems.

Fill out a timesheet in military time, share your files on that platform, but not as a PDF, only a doc, your email that you read on your phone has somehow vanished on your desktop, oh, and don't EVER click the link. If you find yourself overwhelmed and frustrated by systems that claim to make work easier, you're not alone. McKinsey reports that employees spend 1.8 hours every day searching and gathering information.

6

A Compucom survey cited that the average employee faces 18 technical frustrations during the work week.

7

Too many deliverables.

When technology, the economy, and competitors are changing quickly, the project roadmap changes too. And rarely are things removed – they're just piled on. In a multinational survey with more than 1,600 responses, through various industries, only 6% of people say they do

not

experience stress at work.

8

So, turns out, most of us are lying awake at night ruminating, at least some of the time.

This research isn't compiled from the “worst companies ever” list. These things (though incredibly frustrating) are normal. Annoyance is an inevitable part of the work experience, but what you do in the face of it is your choice. With the exact same annoyance, one person will be derailed for weeks while another rolls their eyes and moves on.

We want work to be joyful, meaningful, and a gateway to opportunities. But, our purest intentions of fulfillment are often marred by clunky systems, busy people, and the perils of uncertainty.

Yet somehow these things don't get in everyone's way.

You'll notice that I've left out a very popular grievance: pay.

Because it's not an “always‐present‐must‐accept‐at‐least‐a‐little‐bit annoyance.” It's more malleable.

If you are not being paid a competitive wage, based on your skills and the value you provide to the organization, you're in a gray area. You may accept that less‐than‐stellar paycheck in exchange for more flexibility, better benefits, or an exceptional work environment. You may know that your salary now is only temporary, with a clear path to substantial raises in the not‐distant future. You may be slightly grumbly about it, but not enough to change jobs right now for whatever reason, and that's fine, too.

If you are truly not being paid a living wage, that has to change first. No amount of leading yourself can override food insecurity, a lack of housing, or inadequate medical care. To employ the mindsets of a self‐starter, you must be at baseline economic survival. No company is perfect, but some companies are cruel. We'll talk about more distinctions between “imperfect” and “cruel” but when it comes to compensation, not paying a living wage is cruel. If that describes your employer, you need to put every ounce of mental effort you have into finding a new job. Skip to Chapter 12.

What If …

You might be thinking … but you don't know my boss. You don't know how frustrating my company is. There's no way this could work for me.

Maybe you're right. There's a chance you could diligently employ the strategies in this book and nothing changes. Every shred of research would indicate otherwise, but anything could happen. You're a grown‐up; you can dig your heels into the sand if you want to.

But let me ask you this: What if you started proactively leading yourself … and everything changed?

What if you woke up with more energy?

What if you had a better relationship with your boss?

What if you didn't want to roll your eyes at your inbox or count down until your next vacation?

What if you got to bring the most authentic, ambitious, and engaged version of you to work every day?

What would that feel like?

You might have to power through some awkwardness. There will likely be setbacks, frustrations and disappointments. It won't break you. Really, it's not that hard.

There's a saying I fall back on when I'm getting the courage to start something new.

“The best time to plant a tree was 100 years ago. The second‐best time is today.”

The best time to start leading yourself is when you're starting your first job at age 15. The second‐best time is today.

We all deserve to feel purpose at work. We deserve to have our expertise valued, to have opportunities to grow, and to work with people we enjoy (most of the time).

You have the power to give that gift to yourself.

Part IMindset: Managing the Space Between Your Ears

Our mental frame is a filter through which we process our lives. At work, our mental frame impacts how we perceive our job, our boss, our customers, our company, and even our own contribution.

People who lead themselves lean on four distinct mental abilities that propel their daily actions and work experiences:

They find purpose in the everyday.

They train their brains to avoid mental ruts.

They act in the face of fear.

They can tolerate uncertainty.

As we unpack these four abilities, we'll look at why they work and how you can leverage them in your own work life. We'll also look at the very real obstacles to maintaining these abilities and how you can overcome them.

Chapter 1Finding Purpose in a Normal Job

“Our deepest desire is to make a difference, and our darkest fear is that we won't.”

—Lisa Earle McLeod

A key underpinning of experiencing more joy and meaning at work is knowing that your work makes a difference. Having a sense of higher purpose, knowing that our work matters, is what enables us to feel fulfilled even when things don't go perfectly.

The good news is, you don't have to quit your job and join the Peace Corps to feel greater purpose at work.

If your work impacts your customers, your colleagues, or the communities you serve, you're making a difference. Otherwise, your job wouldn't exist. The challenge is, for most of us, the larger impact of our work is often buried in an overflowing inbox. Or it's passed from department to department, eventually escaping our field of vision.

We're tackling purpose as the first mindset in leading yourself because job satisfaction and long‐term motivation depend upon us knowing that our work counts for something beyond a monetary transaction. Without purpose, feeling engaged is an impossibility.

People who are leading themselves don't wait for the big rah‐rah meeting or the corporate purpose video to feel good about their job. Instead, they tether themselves to a personal sense of higher purpose that fuels them through big goals and tough setbacks. Clarity about how you make a difference (in your regular job) is imperative for energy.

Your company may be changing the world, or they may be just improving the world of accounting. No matter what they're doing, finding purpose in your job is about directing your site line toward the impact of your personal contribution.

Unfortunately, most job descriptions aren't particularly inspiring. They're functional, like a to‐do list. Rarely is it perfectly articulated why the role exists and what impact the role has beyond simply completing the aforementioned functional tasks. Waking up every day to a punch list of disconnected action items is a quick path to burnout.

The consequences of our collective lack of meaning and purpose at work became painfully obvious during COVID.

At the start of the COVID‐19 pandemic, a large percentage of the workforce went home. At first, people were just happy to do their jobs and they jumped in doing what their company needed to stay afloat. But as weeks turned into months, and we began to question if we would ever leave the house again, our adrenaline faded, and we started to ponder: What am I actually doing with my days? Does it even matter?

You probably remember where you were when it started to get “real.” The swanky office sat still, the boujee coffee bar empty, and the glass whiteboards bare.

The peripheries of cheerful colleagues and office perks that made work mostly tolerable faded away. All that was left was you, your laptop, and the work.

In a crisis, you tend to reevaluate your life. Something like a job loss, a health scare, or a death in the family stops you in your tracks. You ask yourself: Who am I? What am I doing with my life? Am I happy where I am?

Typically, these kinds of existential experiences happen (mostly) in isolation, to a singular person or family facing a challenge. At any given time only a small percentage of the population is thrown into “reflection” mode.

But in 2020, it happened on a global scale. Personal reflection occurred en masse and it fundamentally changed the way we live and the way we work. To be clear, people have always craved purpose and meaning, but historically, most of us settled for a paycheck, some perks, and a nice work environment. Not anymore.

A portion of those people are probably happier now. This pandemic‐induced awakening gave many people the courage to leave abusive bosses, toxic work environments, and dead‐end paths. However, for most of those people, making a massive career change didn't deliver the inspirational high that they were hoping for.

For millions of people, the way work had been done before was no longer cutting it. The Great Resignation ensued. People changed jobs or industries or completely reconstructed their lives in the quest for fulfillment.

In fact, inspiration was so apparently lacking in these new opportunities that many returned back to the job they left. A 2023 Harvard Business Review report showed that 28% of new hires in a multi‐year study were boomerang hires (employees who had resigned within the previous 36 months).1

Further research reported that 43% of people who resigned during the Great Resignation admitted they were better off at their old job and 41% felt they quit their job too quickly.2

Despite significant numbers of people making moves to seek more meaning and purpose at work, employee engagement remained relatively flat during this time of upheaval. According to Gallup, in 2012, 33.6% of the US workforce was actively engaged, meaning nearly 70% of people were not emotionally invested in their jobs.3 A decade later, the numbers remain almost unchanged. In 2022, 32% of the US workforce was actively engaged (a scant 1.6% lower than 10 years earlier).4

So, as the saying goes, the grass isn't always greener. Despite a massive shift in the job seeker landscape, plus substantial raises and incentives, things are kind of … the same.

The Purpose Backstory

The quest for purpose that fueled the Great Resignation isn't a new human aspiration. Our search for meaning has been eternal. For centuries, in every part of the world, people have expressed a fundamental desire to make a difference.

The first traces of “purpose” as a concept date back to about 350 BCE. Aristotle often referenced the Greek term eudaimonia, a broad concept used to describe the highest good humans could strive toward – a life “well lived.”5 For many years, scholars translated eudaimonia to mean “happiness.” Now we know the concept is more nuanced than that. Eudaimonia is actually closer to “contentment through virtue.”

Over the span of a few centuries, the idea of “purpose” wove its way through the world, becoming the core of religions, the galvanizing force behind revolutions, and the inspiration powering breakthrough innovations.

Eventually, purpose made its way from a philosophical musing to a cornerstone of the working world. Contrary to what the purpose‐washing headlines of the 2020s would lead you to believe, purpose in the workplace isn't a recent development.

If you've spent any time on the internet, you've likely seen the “Ikigai” graphic, a Japanese concept that emerged a few thousand miles East and a few centuries after Aristotle.

It looks so straightforward in