Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

At a time when the Royal Navy was the biggest and best in the world, Georgian London was the hub of this immense industrial-military complex, underpinning and securing a global trading empire that was entirely dependent on the navy for its existence. Philip MacDougall explores the bureaucratic web that operated within the wider city area before giving attention to London's association with the practical aspects of supplying and manning the operational fleet and shipbuilding, repair and maintenance. His supremely detailed geographical exploration of these areas includes a discussion of captivating key personalities, buildings and work. The book examines significant locations as well as the importance of Londoners in the manning of ships and how the city memorialised the navy and its personnel during times of victory. An in-depth gazetteer and walking guide complete this fascinating study of Britain, her capital and her Royal Navy.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 424

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

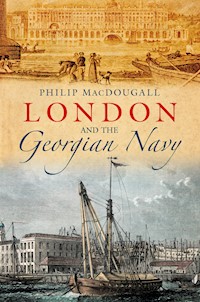

Front cover illustrations. Top: Somerset House from the south or riverside, c. 1820; below: The naval dockyard at Deptford in 1810.

Contents

Title

Introduction

1 Prologue: Death of a Hero

PART 1: The Administrative Hub

Introduction

2 The Admiralty

3 The Civilian Boards

4 Conflict in the Metropolis

PART 2: The Downriver Naval Industrial Complex

Introduction

5 Limehouse Reach: the Underpinning Foundation

6 The Naval Multiplex of Kentish London

PART 3: The Social Dimension

Introduction

7 Those of the Lower Deck

8 The Officers of the Quarterdeck

PART 4: Merchants, Tradesmen and Profiteers

Introduction

9 Finance and the City

10 Cheats and Racketeers

A Gazetteer and Walking Tour

Bibliography

Plates

Copyright

Introduction

While many books have been published on the history of London, none have concentrated on the metropolis and its associations with the Royal Navy. Yet, as I demonstrate in this book, there were few areas of the capital that were not, in some way, either connected with the Navy or dependent upon it for survival and growth.

The most obvious connection was that London was the centre where all decisions relating to the Navy were taken and then actioned. Here, the Palace of Westminster and Downing Street were important players in the decisions taken as to levels of funding and how the fleet would be deployed. In addition, the Admiralty possessed a number of administrative buildings strung across London, together with supply and manufacturing bases that turned a government desire into actuality.

As for the City, London’s original business zone, this was no less connected with the Navy. During the Georgian period the City was dominated by expanding mercantile companies together with the banks. Indeed, it was entirely dependent upon the sea service for its very existence. Without the Royal Navy there would have been few possibilities for growth, given that the City’s financial expansion was very much dependent on overseas trade. Fundamentally, the Navy ensured the existence of safe sea lanes that permitted extensive numbers of London-based companies to embark upon overseas trade in the first place. Of equal importance was a strong and powerful Navy able to support overseas military expeditions of conquest that also created trading monopolies controlled by the larger City trading enterprises. And this goes without even mentioning the Navy’s own insatiable desire for materials, much of them met by London-based merchants operating through the city markets. In fact, the Navy was as dependent on the City, as the City was upon the Navy. While the latter provided security for overseas trade, the City ensured that the infrastructure (including credit facilities) was available for the Navy to expand in unison with trade.

Another important connection with the Navy existed to the east of the City and in many of those outlying parishes that were part of the great urban conglomeration. Administratively separate from London they might have been, technically falling into the counties of Essex, Kent and Middlesex, but physically they were either indistinct or, in the case of Kentish London, rapidly becoming indistinct by way of geography and common pursuit from the city. Here existed the Navy’s industrial base: various dockyards, both private and government owned, that built and repaired many of the Navy’s ships while also housing the artisans who carried out this skilled work. Nor did it stop there, for on the east side of London were various centres for the processing and storage of food as required by the crews of these same warships together with storage areas for various items of ships’ equipment including ordnance.

And the connection still does not end. A sizeable proportion of any crew that manned the Navy’s warships would also be drawn from London. Many ships had 30 per cent or more of their crew drawn from the London area. This particularly applied to the lower deck, the seamen who carried out the labour-intensive tasks of moving the sails and manning the guns. For the most part they also came from the east side of the metropolis, an area dominated by the shipping world and so spawning trained seamen in great number. In total contrast, the more affluent areas to the west were home to many officers of the quarterdeck, not necessarily born and bred in London, but living there because of its proximity to the Admiralty.

1

Prologue: Death of a Hero

Georgian London and the Royal Navy were a completely intertwined entity. Each and every sector of the great metropolis was connected in some way with the sea service. The most palpable of these links was direct employment, with thousands of Londoners at various times having either served on board a ship of war or contributed to the work that kept the Navy at sea. Far less obvious was the connection that most others in London also had with the Navy, through the fact of London’s wealth being dependent on the ability of the Navy to protect overseas trade. London was entirely reliant on this trade, being a great commercial city that had been created to sustain the merchant and the financial profits he generated. Everyone who lived in London benefited in some way from the Navy. It was a symbiotic connection but, because of its partial invisibility, many were quite oblivious of this uncontracted bond.

How could it be otherwise? The near-destitute crossing sweeper or marginally better off waterman might make few connections between the possession of an income, however minimal, and the wealth that supported the complex infrastructure of which they were a part. But recognition of the Navy as special was something they did share with those who, through being more closely connected with commerce, were more aware of how the naval and commercial world were mutually dependent.

Of course, there were down sides to this close association, and these affected Londoners in different ways. Most obvious was the expense of maintaining such a force: this was borne by those with any sort of income. And even if you could not afford to pay for the Navy, you might end up serving in it. The press gang was only one way that the Navy recruited men to its service. But any resulting concerns were seemingly put aside when the capital was mourning a naval loss or celebrating a triumph. Sea battles, in particular, would result in adulatory crowds, celebratory banquets and gifts galore poured upon those who had orchestrated such a masterful stroke. Similarly, anyone perceived to have failed or to have acted against the immemorial traditions of the service, would find a London mob stoning the windows of their town houses or having an effigy of their likeness publicly burnt.

The Battle of Trafalgar, resulting in the destruction of a combined French and Spanish fleet, was one of the most decisive naval engagements ever fought. It brought London’s adulation of the Navy to new heights. Yet the tone of the celebrations was tempered by the loss of the city’s favourite admiral, the often controversial Lord Nelson. As one London newspaper, TheTimes editorialised:

That the triumph, great and glorious as it is, has been dearly bought, and that such was the general opinion, was powerfully evinced in the deep and universal affliction with which the news of Lord Nelson’s death was received. (The Times, 7 November 1805)

Suggestive, indeed, of a widely held viewpoint was the notion, also pursued by TheTimes, that:

There was not a man who did not think that the life of the Hero of the Nile was too great a price for the capture and destruction of twenty sail of French and Spanish men of war. (TheTimes, 7 November 1805)

TheMorning Post, another widely read London newspaper, put a different spin on the event, but still regarded the loss of Nelson as a tragedy:

But while we mourn at the fate of Britain’s darling son, we have the consolation to reflect that he has closed his career of glory by a work that will place his name so high on the tablet of immortality, that succeeding patriots can only gaze with enthusiasm, scarcely hope to reach the envied elevation, whilst a nation’s tears, to the latest period of time, will drop like so many bright gems upon the page of history that recalls the fall of the great hero. (The Morning Post, 7 November 1805)

Although the battle itself had taken place on 21 October 1805, the news was not confirmed until a dispatch from Admiral Collingwood arrived at the Admiralty in Whitehall during the early hours of Thursday 6 November. This told of ‘a complete and glorious victory’ but one tainted by the loss of him ‘whose name will be immortal and his memory ever dear to his country’. First Lord of the Admiralty, Charles Middleton, 1st Baron Barham, having been awoken at 1.30 a.m., immediately set about ensuring that the news was taken to the King, then at Windsor Castle, and various ministers of state. Among the latter was Prime Minister William Pitt; an Admiralty messenger took the news to nearby Downing Street. Pitt was awoken from his sleep, something to which he was not unaccustomed, although on this occasion he was unable to return to his repose, continually reflecting on the image of the ‘immortal Admiral’ whom he had so recently spoken to in that very house.

News of Trafalgar now began to spread by word of mouth, helped by the publication of an ‘extraordinary’ edition of the government-authorised London Gazette together with a second, late morning edition of some of the London newspapers. For those who, by mid-morning, were still not in the know, a hint of something unusual having taken place was given by the firing of an accolade of guns in Hyde Park and on the Tower. Yet, through the loss of Nelson, feelings towards the victory were mixed, resulting in a confused response. While guns may have been blazing away in the morning, many of the owners of larger houses around the city, who would normally have bathed their mansions in a blaze of light, merely showed a few plain lamps in the windows, these soon to be joined by wreaths that bore the telling motto, ‘Nelson and Victory’. The theatres of London also reflected this ambiguity. The Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, in an impromptu addition to the evening performance, had on stage statuesque naval heroes and a half-length portrait of Nelson that carried the epigram ‘Horatio Nelson OB 21st Oct’.

It was not until the following day, Thursday 7 November, that full details of the battle really became available. The morning editions of all the London papers carried the unedited copy of Collingwood’s dispatch that had appeared in the London Gazette Extraordinary.

By now, others had considered how they would treat the event. In particular the larger business institutions of the City, in contrast to the muted lighting to be found elsewhere, elected to emphasise their indebtedness to Nelson and the Royal Navy by heavily decorating the exterior of a number of key buildings. The Guildhall, with a bust of Nelson as a centrepiece, was emblazoned with a crown and anchor over the front of the building, while India House, the home of the East India Company, was decorated with lamps that were offset by a huge anchor motif to the front and stars on each side of the building. So impressive was this particular display that ‘it was hardly possible to move along the street’ due to the illuminations having ‘attracted such a crowd of people’ (The Morning Chronicle, 8 November 1805). At the Theatre Royal in Covent Garden, music was now added to the original impromptu display while at Drury Lane, performances were ending with a rousing chorus of Rule, Britannia!

The behaviour of those from the seamier underside of the metropolis, otherwise known as the London mob, was also strange. Normally, the mob could turn any piece of sensational news into several nights of lawlessness, but it too was muted, for not ‘a single pane of glass was broken from one end of the town to the other’, with the knowing correspondent of TheMorning Chronicle explaining that while ‘the voice of the mob is in general more imperative’ on this occasion its views were exercised in ‘moderation’ (The Morning Chronicle, 8 November 1805).

As the weekend approached, so did one of London’s grandest annual events: the banquet at Mansion House that honoured the newly elected Lord Mayor, on this occasion, Sir James Shaw. Attended by the elite of the City and those in London that the City most wished to impress, the guests included royalty, high-ranking ministers of state (including the Prime Minister) and leading merchants. Among those also invited were the Russian, Prussian and Turkish ambassadors. Inevitably, therefore, every effort was made to emphasise both the importance of the recent victory and the capital’s commitment to the on-going war against Napoleon’s France. To this end, Nelson became a useful point of focus, with the TheTimes on the morning of the banquet reporting:

The preparations made for the dinner on this day are on a very grand scale. The inside of Guildhall is adorned with different devices. The whole length portrait of Lord Nelson is removed out of the council chamber, and placed over the seat of the Lord Mayor, with a prodigious number of lamps, and the flags of the different nations he has conquered. At the Sheriff’s table is placed a bust, in marble, with the brow of the conqueror of the Nile adorned with oak and laurel leaves. (TheTimes, 11 November 1805)

Lloyd’s, through its particular connections with maritime trade, was another London institution heavily indebted to the Navy. At that time housed in the Royal Exchange, Lloyd’s showed its gratitude through establishing in July 1803 the Patriotic Fund that provided grants for those wounded while in the service of the Crown. Trafalgar, although a British victory, had resulted in a considerable number of British seamen suffering death or injury. At a special meeting of the fund management committee, held on 14 November, it was agreed that a further appeal should be sent to both existing and possible new subscribers, with pledged sums accepted by all branch banks within the greater metropolis and also at the bar of Lloyd’s Coffee House. By mid-December, over £23,000 had been received, with Lloyd’s and its subscribers contributing the greatest amount but with additional sums also received from collections made in churches. This was made easier by the King declaring Thursday 5 December as a day of General Thanksgiving to Almighty God. Temple Church and Lincoln’s Inn Chapel, which were frequented by the legal fraternity, raised £321 and £181 respectively.

For most Londoners, the desire to celebrate the victory at Trafalgar was impeded by an equal need to mourn the loss of the hero. Giving generously to church collections on the day of remembrance was, in itself, a significant act that helped resolve the problem while helping reinforce the clear line that stood between celebrating the victory and grieving for the dead. In placing notes and coins into the collection plates, many were heard to mention the name of Nelson with a sigh. Of even greater importance, and further assuaging London’s desire to memorialise the man who had led the fleet, was that Nelson was soon to be honoured with a state funeral. Admittedly, in his will, Nelson had requested that he be buried alongside his reverend father in the churchyard of Burnham Thorpe, but he had then conveniently added ‘unless his majesty should be graciously pleased to direct other ways’. Almost certainly, if Nelson had not provided the necessary codicil, the request in his will would have been ignored, since it had become an essential national requirement that St Paul’s Cathedral should be his final resting place.

The planned funeral procession, which would pass from the Admiralty in Whitehall, into the Strand and then along Fleet Street, would have the advantage of providing a suitably extended route that would allow thousands of Londoners to line the streets and be part of the final act. Previous to this, the general populace was also to be given the chance of paying its respects to the body lying in state at the Seamen’s Hospital in Greenwich.

It was on board Victory, the flagship at Trafalgar, that Nelson was returned to England, secured in a complex arrangement of coffins that saw the body directly placed in one of elm, the timber for this previously taken from L’Orient, a French ship destroyed at the Battle of the Nile. In turn, this elm coffin had been placed into a completely sealed lead coffin, before the two were placed in a much larger one also made out of elm. With Victory anchoring off Sheerness on Sunday 21 December, the body was then transferred on the following day to the Seamen’s Hospital at Greenwich, carried up river by the naval yacht Chatham. Arriving just after 1 p.m., the triple coffin arrangement was taken off at dusk and carried by some of the crew of Victory to King William Court and the vast Painted Hall.

However, the coffin viewed by the general public on the three days of lying in state was outwardly different from the one that was brought from the Mediterranean. Instead of the plain elm exterior, something much more magnificent had been added. Designed by a number of leading London craftsmen, the publicly seen coffin was of mahogany and decorated with a series of panels representing national symbols or Nelson’s past deeds. Included, for instance, was a lion holding the union flag and a crocodile that represented the victory at Aboukir Bay.

During Nelson’s lying in state, the Painted Hall was hung with black cloth and brilliantly lit by fifty-six candles in silver holders. Placed at the upper, raised end of the hall was the decorated mahogany coffin, covered by black drape with only the foot uncovered. Set around the coffin were various flags, including ten placed a few steps back and emblazoned with the single emotive word: Trafalgar.

This was the opportunity for which much of London had waited: the chance to directly pay respect. With Sunday 5 January set aside as the first day, the township of Greenwich was thrown into total confusion. All regular stagecoaches travelling to Greenwich were packed, with the passengers they disgorged into the town joined by hundreds more who had travelled by hackney carriage. Accidents by the score were reported to litter the roads around Greenwich, and a number of carriages overturned in their haste to reach the sought destination. Adding to the confusion were many thousand pedestrians thronging the roads out of London, all making their way to the gates of the hospital. Chaos reigned supreme! Matters were not helped when an official announcement that the hospital would open at 9 a.m. was later countermanded by an instruction that, due to a service taking place in the Painted Hall, the gates of the hospital would remain closed until 11 a.m. This ensured that by mid-morning a great and eager multitude had assembled. Upon the gates being opened, and despite attempts to limit entry, the crowd simply pressed forward:

The scene now became very alarming. The most fearful female shrieks assailed the ear on every side. Several persons were trodden underfoot and greatly hurt. One man had his eye literally torn out by coming into contact with one of the entrance gateposts. Vast numbers of ladies and gentlemen lost their shoes, hats, shawls and the ladies fainted in every direction. (The Morning Chronicle, 2 January 1806)

Fortunately, on approaching the Painted Hall and the steps that provided access, matters were better organised and a large contingency of the Greenwich Volunteers ensured a single-file entry and exit.

On the following day, through the arrival of the King’s Life Guards, accidents were much reduced. Of events on the third day, TheTimes provided a graphic description:

The steps leading up to the entrance of the Great Hall was the principal scene of contest; and curiosity, the ruling passion of the fair sex, rising superior to all of the suggestions of feminine timidity, many ladies pushed into the crowd, and were so severely squeezed, that many of them fainted away, and were carried off apparently senseless to the colonnade; we were however highly gratified that they were rather frightened than hurt and that no injury occurred more serious than a degree of pressure not altogether so great as could be wished. (TheTimes, 8 January 1806)

Elsewhere in London, plans were going ahead for the organisation of the actual funeral, with considerable responsibility placed into the hands of the Royal Heralds and the College of Arms. Traditionally responsible to the Sovereign for all matters connected with heraldry, it also had a general responsibility for the organisation of large state occasions. It was this body that announced that the public would be admitted to the hospital at 9 a.m. each morning, so helping create the chaos that descended upon Greenwich on the Sunday. It was the College of Arms that would establish orders of precedence, requiring that nobility, clergy and gentry who wished to join the public funeral procession from the Admiralty to St Paul’s Cathedral should supply their title, names and addresses. With this information they would be ‘ranked in the procession according to their several degrees, dignities and qualities’. It was also laid down that dress was to be mourning, with any servants in attendance to be similarly attired.

It is at this point that another hero of the age, albeit the fictional creation of C.S. Forester, enters the story. This is Horatio Hornblower, then a newly appointed captain in the Royal Navy and charged with overseeing the transfer of Nelson’s body from the Seamen’s Hospital to Whitehall Steps. As with the funeral procession itself, this was to be a highly formal occasion, with the College of Arms once again playing a leading role. For this reason, Hornblower has to meet with Henry Pallender, described as the Blue Mantle Pursuivant at Arms at the College of Heralds. Undoubtedly, Hornblower was referring to the Bluemantle Pursuivant of Arms in Ordinary, a junior officer of the College of Arms, a post at that time held not by Henry Pallender but by a certain Francis Martin. At the meeting Hornblower receives details of the task ahead of him:

Along the processional route apparently there were fifteen points at which minute guns were to be fired, and His Majesty would be listening to see that they were properly timed. Hornblower covered more paper with notes. There would be thirty-eight boats and barges in the procession, to be assembled in the tricky tideway at Greenwich, marshaled in order, brought up to Whitehall Steps, and dispersed again after delivering over the body to a naval guard of honour assembled there which would escort it to the Admiralty to lie there for the night before the final procession to St. Paul’s. (C.S. Forester, Hornblower and the Atropos, 1953, Ch. 1)

Although in the book Hornblower encountered a problem with the funeral barge he commanded, when it sprang a serious leak and nearly sunk, no such difficulty was encountered in reality. On Wednesday 8 January, Nelson’s coffin was carried out of the Painted Hall to the northern gates of the hospital that led to the river. Proceeded by 500 Greenwich Pensioners together with a royal band of fifes and drums playing the Dead March from Saul, it was followed in turn by Sir Peter Parker, Admiral of the Fleet and chief mourner, together with his supporters and assistants. Also in attendance were numerous naval officers including six lieutenants from Victory:

The body being placed on board the state barge, the several members of the procession took their place on board their appointed barges, when the Lord Mayor of London Corporation, proceeded from the Painted Chamber, uncovered, to the river side, and went on board their respective barges, appropriately decorated for the solemn occasion, the great bell over the south-east colonnade chiming a funeral peal the whole time. (TheTimes, 9 January 1806)

The barge, rowed by sailors from Victory, carried Nelson’s coffin along the Thames towards the City. A flood tide flowed in its favour, but there was a strong wind blowing against the barge.

Along the banks from Greenwich to Westminster Bridge, an immense concourse formed, while to witness the carriage of the coffin from Whitehall Stairs to the Admiralty, the overlooking windows and streets were crowded with spectators.

With Hornblower much relieved that his charge did not sink below the waters of the Thames, and with the coffin safely secured within the Admiralty, the final act was now about to commence. This was the ceremonial carriage of the coffin to St Paul’s Cathedral and the service of interment. Everything now hinged on the Court of Arms having thoroughly prepared for that day. With the eyes of the nation and hundreds of thousands of Londoners wishing to play their part, nothing could be permitted to go wrong. Among the best prepared were the owners of buildings that stretched along the Strand and Fleet Street, many of them having advertised the availability of their windows to those who might be interested. In various London newspapers, adverts, including this one in TheTimes, appeared in the days leading up to the funeral:

LORD NELSON’S FUNERAL. – LADIES and GENTLEMEN may be accommodated with SEATS to see the Grand PROCESSION, on the First Floor, having a commodious bow window, commanding an expansive view of St Dunstan’s Church nearly to the Old Bailey. Enquire at No. 184 Fleet Street. Please ring the bell.

A vast number of labourers were fully occupied during the night that preceded the funeral, cleaning and laying gravel along the length of Whitehall, the Strand and Fleet Street. Just as the labourers completed their work, and with morning beginning to break, volunteer units, such as the East London Militia, the Royal York Marylebone Volunteers and the East India Regiment, began to take up position along the now cleansed length of the three thoroughfares. At Hyde Park too, mounted Life Guards were also present at this unusual hour. They were responsible, under instruction from the College of Arms, for assembling the arriving carriages that would be joining the procession before leading them across Piccadilly, into St James’s Park and through Horse Guards to the Admiralty. A failure to ensure that the officers were fully versed with their task was to create problems later in the day, when it was discovered that not everyone had been correctly placed by rank, quality and status, requiring an impromptu reorganisation outside the cathedral and thus causing one unnecessary delay.

At half past ten, the procession set out from the Admiralty, led by the Duke of York at the head of several regiments. Following immediately behind were twelve marines and forty-eight seamen who had served under Nelson. They were playing a particularly important role in the day’s events and drew a firm connection between the battle and those who had suffered. The College of Arms had also bestowed upon itself a particularly important position within the procession, with messengers of the College, the Blue Mantle Pursuivant and the Rouge Dragon Pursuivant of Arms, all in separate carriages, among the front rank. As for the nobility, still not in order of status, they were immediately in front of the coffin that had been placed on a funeral car designed to take on the appearance of Victory through having been given a stern carved in naval fashion.

At St Paul’s Cathedral, several tiers of seating had been set aside for the public, with these fully occupied by 7 a.m. To prevent the remaining reserved seats being similarly taken, 200 members of the London Regiment of Militia had been ordered on guard. Fortunately, for the dignity of the College of Arms, they were completely successful in carrying out this arduous use of their military training. As for the funeral procession, this did not even begin to arrive at the cathedral until well past midday, with a two-hour service not to commence until around 4 p.m. As such, one has to marvel at the dedication of those members of the public who had to remain in position for over nine hours, since the slightest attempt to move would almost certainly have resulted in the loss of that precious seat.

Much now went as might be expected: those who formed the funeral procession having arrived and entered, anthems were sung, orations given and the coffin finally brought to its assigned area beneath the great dome. Here, the stone floor had been cut away, allowing the coffin to be lowered directly into the crypt. First though, the dean of the cathedral read the remainder of the funeral service, with a herald from the College of Arms proclaiming the style and title of the deceased and concluding with a full description of the merits of Lord Nelson. Now the ceremony of lowering the body began, continuing for about ten minutes, during which time the building was in total silence. Breaking into the planned arrangement, however, were the actions of the crew of Victory who had escorted the coffin. At the end of the ceremony it had been intended that they should carefully furl the scarred battle flags that Victory had flown at Trafalgar and which covered the coffin. However, instead of following their instructions, the crew tore the flag in strips, each taking a piece as a memento of the commander they so admired.

Two notable absentees were the Prime Minister, William Pitt, and the King. For his part, Pitt had the perfect excuse. Terminally ill, he had less than two weeks of life ahead of him and was at the time of the funeral convalescing in the spa resort of Bath. As for the King, such an event was probably viewed as beneath his dignity. But much more important, in the case of Nelson, the King was one of the few people in the country who despised the man, disapproving of the way Nelson had discarded his wife and embarked on a very public relationship with Emma Hamilton. Invited to a levee at the Palace of St James shortly after the Battle of the Nile, the King, aware as he was of the relationship with Emma Hamilton, had asked of Nelson a question but then pointedly turned away before the answer was given. Nor did Nelson’s success at Trafalgar temper this lack of regard, for on receiving the news at Windsor the King certainly expressed his regret but went on to dictate a letter that bestowed all of his praise upon Nelson’s second-in-command, Lord Collingwood.

With London having now laid to rest the man who had masterminded the great triumph, attention could be given to how best to maintain and make use of this acquired seaborne supremacy. Much of Nelson’s legacy was to be in the hands of London’s merchants and traders, who now had a further assurance that vessels sent out would be even safer while at sea. For this reason, ever-greater numbers of ships began to leave the wharves and newly built docks along the banks of the Thames. The decisive victory at Trafalgar and the continued employment of Royal Navy warships throughout the world’s oceans ensured that London (if it did not already) had surely reached the point where it as good as ruled the world.

Part 1

THE ADMINISTRATIVE HUB

Introduction

London was the administrative hub of the Georgian Navy and, as such, the home of a massive bureaucratic infrastructure. Here were to be found the men who ultimately controlled the destiny of the nation, manipulating the world’s largest seagoing fleet to ensure the continuance and growth of London’s dominance over much of the world. While a few of the individuals in the upper echelons of naval administration also appear in the wider annals of history, the vast majority, even if they were generally known at the time, have been lost to subsequently written history. But, known or unknown, they ensured the global presence of the Navy, giving it the ability to defend Britain’s commercial interests wherever they might be threatened. By the end of the Napoleonic Wars, this administrative hub was responsible for the building of warships, the repair and maintenance of over 900 ships in service, the recruitment, provisioning and medical needs of 130,000 seamen, and the delivery of stores to meet Navy and Army needs throughout the world.

Central to this task was the Admiralty, housed on the west side of Whitehall, in a building purpose built to provide office space and residential accommodation. This building primarily served the needs of the Board of Admiralty, an overarching body that took responsibility for all matters relating to the Navy other than that of strategy. Strategy was the responsibility of the Cabinet, of which the senior member of the Board, the First Lord, was always a member. It was his task to advise members of the Cabinet as to the value of any adopted strategy, with the Admiralty, once an order had been confirmed in writing, issuing the necessary instructions for the mobilisation and disposition of both individual warships and assembled fleets. A printed report of December 1787, addressed to George III, described the work of the Admiralty in the following terms:

The business of the board of Admiralty is to consider and determine upon all matters relative to Your Majesty’s Navy and Departments thereunto belonging; to give direction for the performance of all services, all orders necessary for carrying their direction into execution; and generally to superintend and direct the whole Naval and Marine establishment of Great Britain. (Fees Commission, 5th Report, 1)

Not all the members of the Board had naval experience. It was certainly not a requirement of the First Lord, with a number of holders of this post being civilians appointed as much for their loyalty to the party in government as for their experience in the management of a government department. However, this was more likely during the later Georgian period than in the earlier years, with a number of noted seagoing officers achieving this senior naval position in the years leading up to the Napoleonic Wars. Ensuring that naval expertise was always available to the Board, irrespective of any such knowledge held by the First Lord, was that at least one junior commissioner was always a naval officer.

Housed within the Admiralty were the various offices required by Board members, with other rooms set aside for secretaries and clerks. In addition, the building also housed the Marine Office (the headquarters of the Royal Marines) and the Hydrographer (responsible for cataloguing and assembling navigational charts with Alexander Dalrymple, appointed in 1795, the first holder of this office).

For the performance of duties relating to the material side of the Navy and the overseeing of an extensive civilian workforce that included clerics, artisans and labourers, the Admiralty was dependent on a number of civilian boards. Each had its own area of expertise, with none of them housed in the Admiralty. Instead, and up until the 1780s, each of the boards had offices that were on the east side of London and within the shadow of the Tower. Of these, that of the Navy Board was particularly significant, having had a continuous existence since 1660, when it was responsible for overseeing all activities associated with the upkeep of the fleet and those who served in it. However, as warships grew in size and quantity, the Admiralty had concluded that it would be better if a number of specialised boards were created, leaving the Navy Board to concentrate on the material condition of the fleet and control of naval expenditure. The former was undertaken through the Board’s direct management of the government-owned royal dockyards and the issuing of contracts for the building and repair of ships in private yards, while control of expenditure primarily involved the scrutiny of accounts and payments made together with preparing the annual naval estimates and approving payment of seamen and workmen employed in the dockyards.

Among the various boards to be subsequently created were the Victualling, Sick and Hurt, and Transport boards. As for the specialisms that each undertook, the Victualling Board was responsible for meeting the food and liquid needs of British seamen in whichever ships and on whichever seas they served. To undertake this task, the clerical staff employed under the Victualling Board arranged contracts for the supply of provisions while directly administering a number of victualling yards that stored provisions in bulk while undertaking manufacturing and food processing activities. In addition, the Victualling Board also performed a range of similar duties for the Army, arranging bulk supplies for the Army store premises at St Catherine’s Dock, which stood close to the Tower, and establishing contractor-run depot ships for garrison towns abroad. As for the Sick and Hurt Board, this took responsibility for the supply of medicines to warships and all naval facilities, together with the appointment of surgeons and the overseeing of naval hospitals. Finally, the Transport Board was responsible for the hire of ships for the transport of troops and stores and, given that it only existed in wartime, liaising withthe Admiralty to ensure that ships being thus utilised were adequately protected from an enemy attack by naval escort ships.

In addition to the offices of the various boards operating under the instructions of the Admiralty, there were two other bodies linked to the administrative needs of the Navy. Also located on the east side of the capital, they were the Navy Pay Office and the offices of the Ordnance Board. The former served much as if it were the Navy’s private bank, receiving and disbursing all cash sums on behalf of the civilian boards. Whether it was seamen’s wages, officers’ pensions or cash demands by contractors, all payments were handled by the cashier and clerks of the Navy Pay Office. As for the various ledgers that recorded these payments, they were eventually forwarded to the relevant branches within the Navy and Victualling offices where they were audited and filed. The Ordnance Board on the other hand was much more distantly associated with the Admiralty, being technically outside the Admiralty’s domain. Responsible for the supply of guns and other weapons to the Navy, its duties were considerably more diverse as it was also responsible for artillery, engineers, fortifications, military supplies, transport and field hospitals. While not falling directly under the hierarchy of the Army, the most senior member of the Ordnance Board, the Master General of the Ordnance, would always be drawn from the senior ranks of the Army and would, accordingly, sympathise with the needs of the land forces rather than the Navy.

This splintering of naval bureaucracy, combined with a tendency for each of these bodies to claim varying degrees of independence, resulted in the Admiralty not always being in a position to fully implement the orders and instructions it had issued. The Boards, seeing themselves as professional experts, would challenge the Admiralty, questioning the correctness of an Admiralty requirement, especially when influenced by the need to overcome technical or logistical difficulties. These might be unseen by members of the superior board whose concerns were those of seagoing fleets rather than the difficulties of building and designing ships or ensuring that essential quantities of stores could be suitably gathered. In the case of the Ordnance Board, a further range of difficulties emerged, with a natural desire on the part of that Board to prioritise the needs of the Army with this resulting in less attention to naval ordnance.

2

The Admiralty

The Admiralty’s location was dictated by the land in Whitehall upon which it stands becoming available for development. This was in 1694 when an earlier property, Wallingford House, the family home of the Villiers, had been razed to the ground. Coincidentally, Wallingford House was already connected with the Navy through George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham (1592–1628), having been First Lord of the Admiralty and using the house to conduct the business of the Navy. Furthermore, the Lords of the Admiralty continued to meet here until 1634. Upon its demolition the Lords of the Admiralty were able to strike a deal with the leaseholders and trustees of the site for construction of ‘a new house for an Admiralty office’ (TNA ADM2/174, f.455). Construction was soon under way and the building was completed by June 1694. However, this was not to be the building occupied by those who administered the Navy during the Georgian era. For, although the new office was a sizeable building that had been constructed of ‘well-burnt brick and substantial timber’, it was of a poor standard (Survey of London: Vol. 16, pp. 45–70). Leastways, within thirty years, the Admiralty required the building to be replaced by an entirely new structure on the same site.

It is to the Admiralty, still referred to at this time as Wallingford House, that greater attention now needs to be given. It was in February 1723 that the Lords of the Admiralty determined to move forward on the construction of this building, placing before the King in council a memorial that outlined the poor state of the office and the proposal that ‘the same shall be taken down and others erected in their room’ (TNA ADM3/34, 2 February 1723). In giving its approval to this request, the council also agreed to the estimated cost of £22,400. This had been the figure submitted by the Office of Royal Works, with Thomas Ripley the Admiralty’s chosen architect for the project. Previously, Ripley had been employed on the Customs House, a building that, in common with the new Admiralty offices, dramatically failed to keep within the given estimate.

Having gained approval for a new office building, progress was rapid. Within weeks the clerks of the Admiralty had been removed to temporary premises in St James’s Square with the old building completely demolished by the end of May 1723. To facilitate the erection of the offices, the Ordnance Board was induced to remove a small facility they possessed in St James’s Park, as ‘otherwise the said buildings cannot be carried on in the manner directed by his Majesty’s Order in Council’. Although ready for occupation in September 1725, the new Admiralty Office was not completely finished for a further twelve months.

The addition of a later stone screen that was placed in front of the building in 1759 resulted from a request made by the Westminster Bridge commissioners to acquire part of the land that fronted the offices for the purpose of widening the road that ran between Westminster and Charing Cross. In return for the Admiralty’s agreement, which at first was not forthcoming, the Bridge commissioners agreed to pay £650 in compensation and also to provide the Admiralty with an unused parcel of land (24ft by 25ft) left over from the widening programme. To facilitate construction of the road, the Admiralty was also required to demolish an existing wall and ‘to Cause a new stone-wall with one large gate and two doors to the same and other conveniences to be erected … for fencing … so much of the said Admiralty Court-Yard as shall remain after the said Street shall be widened’. The demolition of the old wall and the erection of the new screen was entrusted to Robert Adam, whose accepted estimate of the cost was £1,293 11s. At around this time, use was also made of the additional land acquired from the Bridge commissioners, to the north of the offices and providing space for a porters’ lodge (Survey of London: Vol. 16, pp. 45–70).

The screen represents Adam’s first major work in the capital, with the architect subsequently working on a number of town houses in London. Generally regarded as an architectural masterpiece, the building nevertheless has its critics. According to one early twentieth-century writer, Adam’s 140ft screen together with the Admiralty building ‘harmonise as badly as could be expected of a bluff old sea-dog and a genteel dilettante’ (Hussey, 1923). The screen, not inappropriately, has a naval theme, with engravings of sea horses and prows of a Roman galley and a naval frigate. The latter possesses particular interest, being of the eighteenth century and having its gun ports open and projecting cannons.

One advantage of the screen, apart from it hiding the ill-proportioned Admiralty building with its unnecessarily massive colonnaded entrance porch, is that it protected the building and its occupants from over-enthusiastic Londoners. The screen came into its own in February 1779, when it stood as a barrier to a crowd determined upon laying siege to the building. They were supporters of Admiral Keppel and following his acquittal in a politically charged and motivated court martial were attempting to wreak their vengeance on Vice-Admiral Hugh Palliser, the man who had laid charges against Keppel. At that time Palliser held office as a junior naval lord and the building represented the most obvious symbol of Keppel’s opponent.

A further alteration to the Admiralty complex of Wallingford House was undertaken during the eighteenth century, with construction of an official residence for the First Lord, known as Admiralty House. Before this building was built, the First Lord had been accommodated in Wallingford House (nowadays more commonly referred to as the Ripley Building), thus intruding on space that was under pressure due to a need for more offices. However, it was the lack of privacy resulting from the First Lord having to share his living quarters with the junior lords of the admiralty and the clerks who often worked late into the night that led one holder of the office, Richard Viscount Howe, to request of the Prime Minister in 1783 ‘a few small rooms of my own where [I] might dwell in greater privacy’. Following a discussion in Parliament the proposal, together with a building estimate of £13,000, was agreed. In preparing the site, which immediately connected to the building designed by Ripley, it had become necessary to purchase adjoining land on which stood two houses ‘called Little Wallingford House and Pickering House’. Then owned by Sir Robert Taylor, the purchase was finalised on 16 December 1785 at a cost of £3,200. These houses were pulled down in the course of the following year, with a three-storey building of thirty rooms designed in a simplified form of the Palladian tradition blended onto Wallingford House. Approached from Whitehall, the main front is of brickwork with stone dressing but attracts little attention through it being partially hidden by the Adam screen. Even from St James’s Park, where more of the building was once visible, there was little hint of its true size, appearing only as a square Georgian block with a small, railed garden from which there was (and continues to be) no point of entry (Survey of London: Vol. 16, pp. 45–70; Cilcennin, 1960, p. 9).

Not unnaturally Wallingford House and Admiralty House became familiar to naval officers of the period as it was here that they reported when seeking a new post or being praised on a service performed. Having passed through the porticoed main entrance that gained entry to both buildings, a clerk would make a note of their name, before requesting they sign the First Lord’s Visitors’ Book, to the right of the door. Having carried out these formalities, they would be ushered into the Captains’ Waiting Room, immediately to the left of the entrance. Here they would remain for a varying length of time before being directed into the library of Admiralty House for a meeting with the First Lord.

All this provides a useful starting point for a more detailed examination of the Admiralty complex as it existed upon the completion of Admiralty House in 1788. The hall that stood immediately beyond the porticoed entrance had walls adorned with Doric pilasters supporting a frieze and cornice, while from the ceiling, suspended by a chain with a royal crown, was a lamp of late eighteenth-century workmanship. Also in this entrance hall were a number of leather chairs provided for the porter and doorman. Excessively large for a hallway, it was warmed by a large, open fire with a grey marble surround. The Captains’ Room, although adjacent to the hallway, was entered from a doorway from a corridor to the left. Despite its performance of a fairly mundane task, it was entered through a heavy, oak door with a pediment surround, while the room itself had panelled walls and a vaulted ceiling.

Assuming that the awaiting officer was directed to the library, which was used by the First Lord as a reception room and office, he would cross the entrance hall and continue through a doorway pierced in the old south wall of Wallingford House that gave access to Admiralty House. This brought him to the inner hall, another room designed to impress through it having been given a wagon-vaulted ceiling which immediately catches the eye. A further feature of this room was a cast-iron stove designed as a copy of the rostral column in Rome that had been erected to celebrate a naval war. Again, chairs were in evidence, the ones in this room bearing the Admiralty shield and dating to c. 1722. Ordered at the time when the Ripley-designed building was under construction, they had been made from mahogany specially imported from Jamaica.