5,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

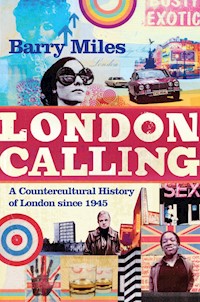

London has long been a magnet for aspiring artists and writers, musicians and fashion designers seeking inspiration and success. In London Calling, Barry Miles explores the counter-culture - creative, avant garde, permissive, anarchic - that sprang up in this great city in the decades following the Second World War. Here are the heady post-war days when suddenly everything seemed possible, the jazz bars and clubs of the fifties, the teddy boys and the Angry Young Men, Francis Bacon and the legendary Colony Club, the 1960s and the Summer of Love, the rise of punk and the early days of the YBAs. The vitality and excitement of this time and years of change - and the sheer creative energy in the throbbing heart of London - leap off the pages of this evocative and original book.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

Copyright

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2010 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

Copyright © Barry Miles, 2010

The moral right of Barry Miles to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Acts of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

wC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

First eBook Edition: January 2010

ISBN: 978-1-843-54613-9

Contents

Cover

Copyright

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Part One

1 A Very British Bohemia

2 The Long Forties: Soho

3 Sohoitis

4 The Stage and the Sets

5 This is Tomorrow

6 Bookshops and Galleries

7 Angry Young Men

8 Pop Goes the Easel

9 The Big Beat

Part Two

10 The Club Scene

11 The Beat Connection

12 The Albert Hall Reading

13 Indica Books and Gallery

14 Up from Underground

15 Spontaneous Underground

16 International Times

17 UFO

18 The 14 Hour Technicolor Dream

19 The Arts Lab

20 The Summer of Love

21 Dialectics

22 Performance

23 The Seventies: The Sixties Continued

24 The Trial of Oz

Part Three

25 Other New Worlds

26 Fashion, Fashion, Fashion

27 COUM Transmissions

28 Punk

29 Jubilee

30 New Romantics and Neo-Naturists

31 Leigh Bowery and Minty

Afterword

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Richard Adams, Kate Archard, Peter Asher, Don Atyeo, James Birch, Peter Blegvad, Julia Bigham, Christine and Jennifer Binnie of the Neo-Naturists, Victor Bockris, Joe Boyd, Sebastian Boyle of the Boyle Family, Valerie Boyd, Lloyd Bradley, Udo Breger, Alastair Brotchie and the Institutum Pataphysicum Londiniense, Peter Broxton, Aaron Budnick at Red Snapper Books, Stephen Calloway at the V&A, Simon Caulkin, Pierre Coinde and Gary O’Dwyer at The Centre of Attention, Harold Chapman, Rob Chapman, Chris Charlesworth, Tchaik Chassey, Caroline Coon, David Courts, David Critchley, Virginia Damtsa at Riflemaker Gallery, Andy Davis, David Dawson, Felix Dennis, Jeff Dexter, Michael Dillan at Gerry’s, John Dunbar, Danny Eccleston at Mojo, Roger Ely, Michael English, Mike Evans, Marianne Faithfull, Colin Fallows at John Moores Liverpool University, College of Art, Nina Fowler, Neal Fox, Raymond Foye, Richard Garner, Hilary Gerrard, Adrian Glew at the Tate Archives, Anthony Haden Guest, Susan Hall, Jim Haynes, Michael Head, Michael Henshaw, John Hopkins (Hoppy), Michael Horovitz, Mick Jones of the Clash, Graham Keen, Gerald Laing, David Larcher, George Lawson, Mike Lesser, Liliane Lijn, Paul McCartney, Owen McFadden at BBC Radio Belfast, Michael McInnerney, Howard Marks, John May, James Maycock, James Mayor of the Mayor Gallery, Susan Miles, Theo Miles, Amanda Lady Neidpath, Thomas Neurath, Jon Newey at Jazzwise, Philip Norman, Melissa North, Lady Jaye and Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, Mal Peachy at Essential Works, John Pearce, Gary Peters, Dick Pountain, Susan Ready, Marsha Rowe, Greg Sams, Jon Savage, Andrew Sclanders at Beatbooks.com, Paul Smith, Peter Stansill, Susan Stenger, Martha Stevens, Tot Taylor at Riflemaker Gallery, Paul Timberlake, Dave Tomlin, Dan Topolski, Charlotte Troy at the Hayward Gallery, Simon Vinkenoog, Anthony Wall at BBC Arena TV, Nigel Waymouth, Mark Webber, Carl Williams at Maggs Brothers Rare Books, John Williams, Mark Williams, Andrew Wilson at the Tate Gallery, Michael Wojas at the Colony Room, Peter Wollen.

To Michael Head for his recordings of my onstage interview with Michael Horovitz (Riflemaker Gallery, 30 January 2007); to Jon Savage for giving me access to his punk interviews, his London photographs and his CD compilations of London songs; to Rob Chapman and also Andy Davis for providing valuable DVDs of archive fifties and sixties TV documentaries; to James Maycock for some extremely rare DVDs; to Owen McFadden for hard-to-find DVDs and CDs of radio and TV programmes; to Anthony Wall for Arena documentaries; to Andrew Scanders for finding tricky sixties documentation.

Special thanks to the Society of Authors for an Author’s Foundation award which enabled me to extend my research. To James Birch, Valerie Boyd, Caroline Coon and Genesis P-Orridge, who kindly allowed me to interview them. To Toby Mundy, Sarah Norman and Daniel Scott at Grove Atlantic, to Mark Handsley for his fine copy-edit – all remaining mistakes are still mine – and, most of all, to Rosemary Bailey for reading and re-reading the manuscript, correcting my numerous mistakes and, as usual, making extremely valuable editorial suggestions.

Introduction

Look at London, a city that existed for several centuries before anything approximating England had been thought of. It has a far stronger sense of itself and its identity than Britain as a whole or England. It has grown, layer on layer, for 2,000 years, sustaining generation after generation of newcomers.

DEYAN SUDJIC, ‘Cities on the Edge of Chaos’ 1

My earliest memories are of London in the forties: watching the red tube trains running across the rooftops, which was how it looked to a three-year-old peering out of the grimy window on the second floor, seeing the Metropolitan line trains on their way to Hammersmith. I remember running with a gang of local kids to buy chips from the fish and chip shop on the corner: they had to hand the pennies up to the counter for me because I was too small to reach it myself. But these were memories of a visit. My parents had lived in London before the war when my father drove a London tram, but my mother returned to her family in the Cotswolds when my father joined the armed forces to fight against the Nazis. Consequently, though I’m told I was probably conceived in London, I was born in the Cotswolds. I always felt there had been some mistake. After demobilization, my father returned to London Transport and drove a bus so we often visited him in London. But the bombing had caused a tremendous housing shortage and there was no way we could join him there. Eventually he got a job in the Cotswolds, and we settled into country life. But I never forgot London and hankered after the city throughout my childhood.

On the bus between Cheltenham and Cirencester I would fantasize all the way that there was a row of houses on each side, blocking out the trees and fields. In 1959, shortly after turning sixteen, I hitch-hiked around the south coast with a friend, a copy of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road in my pocket, spending the nights in barns, with London as our ultimate destination. I had a cousin whose family had been rehoused in a prefab in Wembley and the previous year he and I had explored Soho together, so we headed there, the only part of London I knew. We went to the 2i’s coffee bar and the Partisan coffee house on Carlisle Street, where a bearded man wearing sunglasses at nighttime strummed a guitar and people sat around playing chess and drinking coffee from glass cups. We finished up just down the street, two doors from Soho Square, drinking wine with the waiters at La Roca Spanish restaurant, now the Toucan Irish bar. That night they let us unroll our sleeping bags in the basement among the wine racks and shelves of plates and napkins. To a teenage Cotswold lad, this was the height of bohemian life, just the sort of thing that Kerouac might have done. This was the life I wanted. I was determined to live in London and throughout my years at art college I hitch-hiked to town as often as I could, staying on couches and floors, sometimes even finding a welcoming bed. In 1963 I achieved my aim. I lived in Baker Street, Westbourne Terrace, Southampton Row and Lord North Street before settling in Fitzrovia almost forty years ago.

‘London calling’ were the first words heard on the crackling crystal sets across the nation when, on 14 November 1922, the 2LO transmitter of what would become the BBC first went on the air. Radio was the height of modernity and the phrase caught on immediately, so much so that Noel Coward launched a new show called London Calling! Since then the phrase has had a deep emotional association with the capital. BBC newsreaders always announced themselves with the words ‘London calling’, and throughout the war they brought a message of hope, and sometimes terrible news, to people huddled around clandestine radio sets in Nazi-occupied countries. The BBC made a point of detailing setbacks before the Nazi propaganda machine could use them because in that way people would believe the BBC when there was good news, or possibly the call to arms. Even when Broadcasting House itself received a direct hit, the news reader, Bruce Belfrage, continued his broadcast as if nothing had happened despite being covered in plaster and dust. All listeners heard was a distant ‘crump’ as the music library and two studios were destroyed, killing seven people. Even now, for millions overseas, it is the call signal of the BBC World Service, bringing uncensored news and, for many listeners, free English lessons.

Edward R. Murrow always opened his nightly CBS reports from the war-damaged capital with the words: ‘Hello, America. This is London calling’, drumming up support for Britain in the hope that the Americans would one day enter the war. These days in Britain, ‘London calling’ immediately brings to mind the name of the Clash’s single and their best album, the title of which came from this collective memory. The phrase evokes a melange of feelings: of nostalgia, of history and pride, memories and fantasies. To some in the provinces it provokes a simmering distrust of ‘trendy Londoners’ but to many more it evokes a destination to aspire to, the source of so much wealth, art and culture. Unlike the USA and numerous other countries, Britain combines its cultural, political and financial capital all in one place. To reach the top in any of these areas, you have to move to London. The Beatles PR Derek Taylor was not joking when he suggested that the ‘fifth Beatle’, of endless press speculation, was London; it was London where they did everything that mattered. 2

This book is concerned with the creative life of London and, more particularly, with its bohemian, beatnik, hippie and counter-cultural life since World War Two. As this is not an encyclopedia, I have usually described the people I know, or whose work I am most familiar with, thus the B2 gallery on Wapping Wall, but not the equally significant 2B gallery on Butler’s Wharf; I describe C O U M Transmissions and Genesis P-Orridge but not Bow Gamelan and Paul Burwell, who were doing equally interesting work. The subject of underground rock ’n’ roll is altogether too large for this book, and has been mulled over in hundreds of books already; only with punk bands do I deal with the subject directly. The jazz world and the lives of black musicians and visiting American jazzmen in London should, by rights, be included but it is largely outside my experience. Fortunately Val Wilmer has already written a magnificent history of this subject in her book Mama Said There’d be Days Like These. In fact, to attempt to cover all aspects of avant garde, or transgressive activity in London would have led me ‘into fields of infinite enquiry’, as Ruskin said. I have concentrated on people who make their art their life, who live in the counter-culture, not comment upon it, those who want to transform society, and not necessarily from within. I also wanted to make the book accessible and amusing as humour is an often overlooked side of the avant-garde, so many of the anecdotes are included purely for the sake of levity.

The underground life of any city, Paris, Berlin or New York, and also smaller places like San Francisco, Amsterdam or Copenhagen, is shaped not just by the prevailing social and political situation but also by its built environment: the availability of cheap accommodation, the provision of cafés, bars and meeting places, the existence of galleries or performance spaces, the physical sense of place created by its local architecture. There are always neighbour-hoods where artists and students gather. So it is in London.

Chelsea was once just such an area but in the 1920s many of the streets of working-class houses were demolished to make way for blocks of flats for the rich. The rise of the motorcar allowed developers to dismiss the grooms and coachmen and convert their mews cottages into bijou residences for artistic young people of the sort described in Dorothy L. Sayers’ novels. In 1930 there was an insurrection by tenants armed with ‘thick sticks, clappers, bells and whistles’ resisting eviction to make way for luxury flats. They were overcome by a small army of mounted and foot police accompanied by massed bailiffs. Soon the wealthy newcomers were exclaiming over Chelsea’s delightful ‘village atmosphere’. After the war Chelsea was shabby and run-down but the bomb damage was quickly repaired, and, with a few exceptions such as Quentin Crisp, only the wealthier bohemians could afford to live there.

Soho, on the other hand, had always been the cosmopolitan centre of London, its character formed by successive waves of refugees. Greek refugees from Ottoman rule settled there in 1670, giving Greek Street its name. They were followed by French protestant Huguenots in the 1680s, and more French escaping the Revolutionary Terror of the 1790s. Belgians arrived fleeing the Germans in 1914 and Germans and Italians have been settling in Soho ever since the 1850s. Many Polish and Russian Jews moved there from the East End in the 1890s. But until World War Two, Soho took its character mainly from the French: they had their own school on Lisle Street, a French hospital and dispensary on Shaftesbury Avenue, four churches, including the French Protestant church on Soho Square, and a full supporting cast of restaurants, cafés, boucheries, boulangeries, pâtisseries, chocolateries and the like. When I first came to London in the early sixties, you could buy vegetables and homemade cheese at La Roche on Old Compton Street sent over three times a week by the owner’s French relatives; all the signs were in French and that was the language of the store. The Vintage House down the street sold wine en vrac and the meat at La Bomba was butchered in French cuts. Until the Street Offences Act, most of the prostitutes on the streets of Soho were also French. The French still have a presence in the area now, but most of the community has now settled around the French lycée in South Kensington.

Superimposed on French Soho was Italian Soho, which by the 1940s was of equal importance to the French presence and introduced the British to spaghetti and pizza, olive oil and Chianti. Italian restaurants sprang up all over Soho and are still plentiful. With them came wonderful Italian food stores, some of which survive. Soho was also home to a large Cypriot community and also housed numerous Hungarians and Spanish, and from the seventies onwards came the Chinese, who have now developed their own Chinatown. Almost from the day it was first built Soho has been truly cosmopolitan and remains so. At the end of the war, it was the only place in Britain that had a genuine continental flavour, as the bistros and cafés tried to scrape together meals for a war-weary population. Strange to think that a candle in a Chianti bottle and a fishing net across the ceiling was then considered unbelievably romantic and sophisticated.

Before the war the area north of Oxford Street was often included in the definition of Soho, when it was not referred to as Fitzrovia, and like Soho it had a large continental population, including so many Germans that Charlotte Street was known as Charlottenstrasse. I loved Schmidt’s on Charlotte Street which used the German system of the kitchen selling the food to the waiters, who then sold it to the customers. Inevitably there was hot competition over where the guests sat and fights were commonplace. One of my earliest memories of living in London is of one of the waiters at Schmidt’s shrieking: ‘Hans! Again you haff stolen my spoons!’ and lunging across the huge room wielding a carving knife. Hans escaped through the swing doors.

Regrettably, the re-zoning of Fitzrovia as light industrial to meet the demand for office space after the war let in the property ‘developers’, who lost no time in finishing off the destruction wrought by the Nazis: down came Howland Street and the artists’ studios of Fitzroy Street to be replaced by tacky office blocks, most of which have since been replaced. Down came John Constable’s beautiful eighteenth-century house and studio in Charlotte Street to be replaced by a glass box containing PR companies and advertising agencies, and next door looms the great bulk of Saatchi and Saatchi, replacing a whole block of eighteenth-century houses. The Bloomsbury Group lived in these streets, as did Nina Hamnett and the painters of the Euston Road School. It is entirely appropriate that in twenty-first-century Britain streets that were once filled with artists now contain Britain’s highest concentration of advertising agencies; real artists displaced by the counterfeit, the second rate; creative individuals prostituting their talent.

Not surprisingly then, it was to Soho that people came to get away from Britain for a few hours. It was in Soho that British jazz and British rock ’n’ roll found their beginnings in dozens of late-night clubs; it was in the Soho pubs, like the French, which even today does not possess a pint mug, where bohemia thrived and painters and boxers and students and prostitutes mingled; it was where the bookshops were, and the cheap Greek and Italian cafés, and the drinking clubs, and spielers and brothels, and where even a few art galleries tentatively opened their doors on to bomb-shattered streets.

When I first was first taken to the French pub in the early sixties, I felt immediately at home. In the Cotswolds I had always felt a complete outsider in the pubs with their horse brasses and red-faced gentlemen farmers in cavalry twills and chukka boots. At the French, in contrast, the faces of the clientele were deathly pale, they wore shades and looked like artistic gangsters. They were drinking wine and pastis and there was not one mention of agriculture. It was wonderful.

This book is set largely in the West End; it is there that the magnet which draws people into London is located. The bohemia of Fitzrovia and Soho during the war years drew in the next generation: poets like Michael Horovitz graduated from Oxford and moved straight to small flats in Soho. The beatniks of the early sixties congregated around Goodge Street in Fitzrovia, giving the One Tun as their mailing address, thereby making it the destination of the next wave hitch-hiking in from Newcastle and Glasgow. The underground scene of London in the sixties was perceived as a West End phenomenon: that was where the U F O Club, Middle Earth, Indica Books, the IT offices, the Arts Lab and other centres of activity were located, but by then most of the contact addresses scribbled on grubby bits of paper would have had w10 or w11 postcodes because that was where the cheap housing was.

Only in the nineties did the focus shift further east to e1 and e2, as artists colonized the grim industrial wastelands and tower blocks of the East End proper. Writers such as Iain Sinclair, Peter Ackroyd, Stewart Home and Patrick Wright have staked a claim to the East End as a dynamo of cultural ferment, crossed by ley-lines, studded with vertical time pits connecting the present with the eighteenth century, inhabited by eccentrics and bohemians. Sinclair’s psychogeographical wanderings are especially valuable in making this disparate part of London coherent. But there was pitifully little there in the eighteenth century except market gardens and meadows. It was, and remains, suburban. They have made the best of a landscape of flooded air-raid shelters, the floorplans of long-gone Nissen and American Quonset huts and post-war emergency prefabs; vistas enlivened by the occasional remaining detail on a graffiti-covered Victorian town hall or an unusual allotment hut. They even have a Hawksmoor church or two, but until recently this was not the London that pulls people halfway across the world.

The London of dreams is Swinging London: the King’s Road of rainbow-crested punks and Austin Powers; tourists on the zebra crossing at Abbey Road; Big Ben and the statue of Eros at Piccadilly Circus. It is more specifically the West End, which has been the cosmopolitan centre of London for 300 years: the impeccably dressed old man slumped in the back of a shining chauffeur-driver Rolls-Royce powering up Hill Street in Mayfair at 3 a.m.; drunks trying to find their way out of Leicester Square; it is the late-night drinkers emerging from Gerry’s on Dean Street, blinking in the sunlight as people push past them on their way to work. It is Chris Petit’s Robinson, Colin Wilson’s Adrift in Soho, Michael Moorcock’s Mother London and the Jerry Cornelius novels. Swinging London lives on in the imagination. But the scene has now shifted eastward. Recently, walking down Great Chapel Street in Soho, I overheard two young men talking. ‘You know,’ one of them said, ‘looking at this, you could easily be in Shoreditch.’ It is true; the vast acreage of the East End is now the artistic neighbourhood of London, though it is too spread out to have any real centre: artists have studios everywhere from Hoxton to Stoke Newington to Bow. They do engage with the older residents, but often their studios – where many of them live – are in semi-industrial areas with few people living nearby. There are scores of small galleries, but as soon as they become successful they usually move to the West End.

This book concentrates on the role of London as a magnet and its clubs and pubs as energy centres. With the advent of the internet, Eurostar and cheap European air flights, the importance of London as a location has been reduced as people travel to Barcelona, Berlin, Paris and all over for shows and art fairs, keep up to date with the latest events in New York, Sydney and Moscow on the net, and use Skype to chat to friends working in Vancouver or Amsterdam. Globalization and cheap instant communications mean that no matter how outrageous and cutting edge an event might be, people all over the world can know all about it seconds later; a true underground is impossible now unless the participants are sworn to secrecy. For the same reason, though many artists and musicians use London as their theme, many more could just as easily be working out of Paris or Berlin. This is the twenty-first century, and things have changed.

Before World War Two, London was the greatest city on Earth; by V E Day, 8 May 1945, it was devastated: damaged buildings standing in a sea of stones, bombsites overgrown with weeds, dunes of brick dust, rubble piled alongside hastily cleared streets. Condemned structures stood windows open to the sky, strips of wallpaper hanging in flaps, stairs leading to nowhere. More than a million houses had been destroyed in the blitz, leaving one in six Londoners homeless. Many buildings were occupied by squatters who bravely set up house between walls shocked into strange angles by the bombs, sometimes propped up by wooden buttresses. Cellars were flooded with stagnant, murky water bobbing with detritus and the corpses of rats, and equally dangerous were the emergency static water tanks, large rectangular iron cisterns placed near vulnerable buildings to counter the German incendiary bombs when the water mains were shattered: four foot deep and filled to the top, enough to drown a child. Sheep grazed on Hampstead Heath, there was a piggery in Hyde Park and the flowers of Kensington Gardens had been replaced with rows of cabbages. The city was beaten down, it was drab and monochrome, joyless. There was stringent rationing of even basic food and fuel, poverty was apparent everywhere from the skinny kids playing on the bombsites, the muttering tramps sleeping rough on the Embankment, many of them unhinged by the war, to the tired whores in Soho and Park Lane. But despite the greyness and the smog, some of the pre-war spirit prevailed. The old bohemian areas of Fitzrovia and Soho still had flickers of life in them.

There were communities overlapping in Soho: the local people who worked in the markets, restaurants and small workshops; the sex workers and artists’ models, along with a few painters and writers and the bohemians and eccentrics who patronized the bars and clubs from mid-morning until after midnight. Soho was desperately run down and parts had been badly bombed. Ninety per cent of its population used the Marshall Street baths; Friday afternoon was the usual day for waiters. A first-class hot bath was 6d and second class 2d, cold baths were half-price. People arrived with brown-paper parcels containing their clean clothes, soap and towel. Most of them were the families of Italian waiters who lived in cramped rooms in Dean Street and Greek Street, saving every penny to retire back to Italy and buy a farm. With Mediterranean staples like olive oil and wine virtually impossible to get, these restaurateurs performed miracles daily to produce a semblance of Continental cuisine and provide the ambience necessary to keep the spirit of Soho alive.

Soho was still very much a village despite wartime evacuation and the bombing. The same laissez-faire attitude that had always attracted artists and writers, students and journalists, also attracted strippers and brothel keepers, gamblers and pornographers. Throughout the war it was sustained by thousands of British and American troops who were there more for the brothels and gambling dens than the food but who kept Soho alive, giving it a reputation as a red-light district that still remains in the popular imagination. Hardly a street in Soho was without bomb damage; even St Anne’s was destroyed, leaving its tower standing alone in a mountain range of rubble.

Despite the destruction, many people never left its streets; they would have felt like refugees anywhere else. There is a story about an artists’ model, a regular at the Highlander on Dean Street, who appeared one Saturday morning formally dressed complete with gloves and stockings. She even wore a hat, a previously unseen occurrence. Asked if she was going to a wedding, she replied: ‘No. Going away for the weekend. To Swiss Cottage.’ 3As Sammy Samuels, the owner of a series of spielers or gambling clubs, wrote about one of his clients: ‘he found his way into Soho and so far as I know, has not been able to find the way out. And Soho does get some types of people that way. Maybe it’s the air, or the feeling that you’ve gone “foreign” like in Africa or India, and it’s too good to change.’

There were some artists and writers who were locals but mostly they arrived by taxi, tube or bus to eat and, most importantly, to take up their favourite positions at the bars. The bohemian community of London conducted its business in the pubs and cafés of the streets between Charlotte Street in Fitzrovia and Dean Street in Soho; a few minutes walk. It never took long to find someone you knew because no matter where people actually lived, they always travelled to Soho to meet their friends. The pubs were dingy and uncomfortable and everybody stood. They did not go there for comfort; they were there for the conversation, the ideas, the alcohol and the atmosphere of male bonhomie which few women were permitted to enjoy. Beer was from the barrel, people drank whisky and Guinness and the air was a thick fog of Craven ‘A’ and Senior Service. Soho and its environs were the stage, the various cafés, pubs and clubs were the stage sets, and in them, propping up the bar, were the characters, talking and talking. George Melly: ‘Soho was perhaps the only area in London where the rules didn’t apply. It was a Bohemian no-go area, tolerance its password, where bad behaviour was cherished.’ 4

Part One

1 A Very British Bohemia

It was from the nests in Whitfield Street, Howland Street and Fitzroy Street, with the Fitzroy Tavern for home run, that the idea of Fitzrovianism in the verbal sense was first born… the idea of our group as vagabonds and sadhakas or seekers, as the Buddha was at the start… The fact that the name I gave, Fitzrovia, persists, does not surprise me, because of the unity of spirit and atmosphere which made it unique in London in those days.

TAMBIMUTTU, ‘Fitzrovia’ 1

The underground scene in London didn’t spring into being, ready-formed, at the end of the war. It grew slowly, the product of many factors, and in the early days there were precious few individuals who could really be considered particularly unconventional. The colourful characters of the time like Tambimuttu and Julian Maclaren-Ross would not perhaps have merited so much attention had they lived a few decades later but in the mid-forties they constituted bohemian London.

‘Fitzrovia’ as a name for the neighbourhood was coined just before the war by Tambimuttu, one of the central characters of wartime literary London, a unique publisher and editor, whose magazine Poetry London was a magnet to the most talented of writers in Britain at the time. Meary J. Tambimuttu, known universally as Tambi, was a Jaffna Tamil, born in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) in 1915. 2 He was an attractive, romantic figure, with long silky black hair that required constant jerks of his head to keep it from his eyes. The art dealer Victor Musgrove said that he and Tambi were the only two men in the second half of the forties in London to wear shoulder-length hair. Tambimuttu had tremendous charm, and a naive belief that everything would always work out: printers would be paid, drinks would be forthcoming, he would not starve to death. He was a literary hustler of exceptional ability. He loved literature, particularly poetry, though he encouraged a rumour to develop that he never actually read the manuscripts he was sent, relying instead on instinct and the feel and quality of the paper. Certainly he was known to inform complete strangers that he would publish their poetry, despite never having read it.

I first met him in the sixties when he came into my bookshop. We had numerous friends in common, including Timothy Leary, and he had gossip about them all. Then he quite casually suggested that he wanted to publish my poetry, a suggestion which I found quite extraordinary as I didn’t even write poetry. Despite this he was a superb editor. Unfortunately he was also untrustworthy and dishonest, he borrowed money constantly and did not repay it, he was sloppy and disorganized and lost manuscripts entrusted to his care. On one occasion the only copy of one of Dylan Thomas’s new poems was found in the chamber pot beneath his bed. This is not as surprising as it might seem as, when he finished reading a manuscript, he would reach down the side of his bed and stuff it into the chamber pot, which was used as a rudimentary filing cabinet. He later invested in a cardboard box. He lived mostly in Fitzrovia: 45 Howland Street, 2 Fitzroy Street, and 114 Whitfield Street in a house filled with poets next door to Pop’s café; all now gone, bombed or levelled for office blocks.

His magazine, Poetry London, began publication in 1939. At the end of the war he had offices at 26 Manchester Square (now number 4). The publishers Nicholson and Watson had the first floor and they paid the running costs of PL. Editions Poetry London occupied the front room on the third floor, with Nicholson and Watson in a smaller room at the back. PL’s long windows looked out over the square through the trees to the Wallace Collection opposite. Their room led off a large carpeted landing at the top of a gracious curving staircase. There was an elaborate marble mantelpiece cluttered with invitation cards and memorabilia. Tambimuttu’s desk was between the windows, facing the door. 3

Tambimuttu wore the same clothes until his staff could no longer stand the smell and would insist on him talking a bath. His secretary Helen Irwin remembered the occasions:

In the middle of the morning I would scrub his back. Such was the din – the shouts, the howls, the splashings of water – that you would have expected help to rush up from below. Like a schoolboy Tambi made the most of it, calling through the open door: ‘Nick, Gavin! She’s raping me!’ To which, after a bit of banter, they replied they rather doubted it. 4

Whenever he spent a weekend in the county with friends he liked to run naked through their houses.

Lucian Freud was a frequent visitor to the offices. One of his projects there was to illustrate Nicholas Moore’s The Glass Tower. Freud used to disappear into the green bathroom for up to an hour at a time. When asked what he did in there he replied that he lay in the empty bath and thought. Other visitors included Henry Moore, who did numerous illustrations for the magazine, Edith Sitwell, Elizabeth Smart and Roy Campbell, who was shunned by many on the Fitzrovia–Soho scene because, as a Catholic, he supported Franco’s side in the Spanish Civil War.

The Hog in the Pound, on the corner of South Molton Street and Davies Street, off Oxford Street, was their local. The landlord, George Watling, was sympathetic and never fazed by their outrageous behaviour. When the pub closed at 2.30 in the afternoon they would make their way to the Victory Café, on the left-hand side of Marylebone Lane for a late lunch of sausage and mash or spaghetti bolognese. Before six o’clock, however, Tambi and some of the office staff would set out on what was known as the ‘Fitzrovia’ pub crawl. Tambi originally invented this word to define the action: the Fitz-roving, but it quickly became used by his circle of friends to define the area stretching roughly from Fitzroy Square to Soho Square which had no precise name: it was North Soho, East Marylebone or West Bloomsbury, none of which were satisfactory. Thus Fitzrovia.

The first stop on the pub crawl was, of course, the Hog in the Pound, an hors d’oeuvre before they headed east down Oxford Street first to the Fitzroy, then the Wheatsheaf and on down into Soho, usually finishing at the Swiss Tavern. Tambi ate little and drank a lot, but his contribution to English literature was enormous: he edited fourteen issues of Poetry London, and more than sixty books of poetry and prose, often beautifully illustrated, always well designed, produced from 1938 to 1949, featuring everyone from Dylan Thomas, Louis MacNeice and Stephen Spender to Lawrence Durrell, W. S. Graham and Katherine Raine, He published the first books of Herbert Read and David Gascoyne as well as Henry Moore’s Shelter Sketchbook. He recognized the genius of Elizabeth Smart and published her By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept, the brilliant autobiographical account of her disastrous marriage to Soho poet George Barker that enraged Barker because it was so much better than anything he could ever have written. Tambi introduced British audiences to Nabokov, Henry Miller, Anaïs Nin and scores of other little-known foreign writers.

Tambi died in 1983, when he was living at the October Gallery on Old Gloucester Street, but his spirit lives. Tambimuttu: ‘It was only an attitude of mind that comes to each generation in every country, and in different ways, but for me it happened in lovely Fitzrovia.’ 5

*

The morning after V E Day, in May 1945, the Scala Café on Charlotte Street was filled with artists nursing their hangovers from the celebrations of the night before. The artist Nina Hamnett found the Fitzroy Tavern open but the Wheatsheaf and other local pubs were closed, probably having run out of drink. She lived just two blocks away in two rooms on the top floor of 31 Howland Street, and had to pass the Fitzroy on her way to Soho. She always looked in, but even if that did not detain her for very long, she sometimes got no further than the panelled rooms of the Wheatsheaf. Nina Hamnett more than anyone represented the pre-war spirit of Fitzrovia. 6 Born in Tenby, Wales, in 1890, she had studied at a number of art colleges in both London and Paris, where she famously danced naked as a model for her fellow students, and also became a respected artist in her own right. She experimented with various styles but the majority of her paintings and drawings were portraits: solid, almost sculptural affairs of friends, lovers and often just of people she liked the look of. She exaggerated and simplified her compositions to create what she called ‘psychological portraiture’. She had numerous West End gallery shows and sold quite a bit of her work in the twenties and thirties, but by the forties her work began to suffer badly from her fondness for drink and her busy social life.

Often described as the ‘queen of bohemia’, she had posed in the nude for Sickert, became a close friend of Augustus John and was Roger Fry’s mistress. She had an affair with Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, who made several marble torsos of her and a sculpture of her dancing naked – she was proud of her body and liked to strip off at parties. Artists liked her long slender figure and she was a much sought-after model. She introduced herself to the poet Ruthven Todd by saying: ‘You know me, m’dear. I’m in the V&A with me left tit knocked off ’, a reference to a Gaudier-Brzeska bronze torso of her which had been damaged when the original plaster cast was made. In Paris before the Great War and in the twenties, she knew all the most important artists from Modigliani and Picasso to Diaghilev and Stravinsky. She had countless affairs, and had sex with anyone she fancied. Aside from artists and writers – she took the virginity of 21-year-old Anthony Powell – she had a particular fondness for boxers and sailors. When asked what she liked about sailors she exclaimed: ‘They go back to their ship in the morning!’ By the late thirties she was spending virtually all of her time in the pubs of Fitzrovia and Soho, and hardly any at her easel. She was a great raconteuse, and anyone prepared to buy her a drink was treated to endless – often salacious – anecdotes about her life in the studios of Montparnasse.

By 1945, the tensions of the war years and the effects of alcohol had made a pathetic creature of her. She lived in squalor in Howland Street, with cockroaches and bedbugs, and visitors even reported seeing rat shit on her bedcovers. There was no bathroom – only a communal one on the ground floor – but there was a small washbasin in the corner of the staircase. In February 1947, when her landlady, Mrs Macpherson, took her to court in an effort to empty her house on Howland Street and sell it with vacant possession, she claimed that Nina had ‘misused the sink’. But the magistrate would hear none of it; he interrupted her testimony, saying: ‘What do you mean, a woman urinating in the sink? It is not possible’, and refused to accept her evidence. This caused great hilarity among Nina’s friends in Fitzrovia, who knew that her landlady was perfectly right in her accusation.

A convenient fire in the building shortly afterwards caused her to move out. She took two rooms on the second floor of 164 Westbourne Terrace, near the railway lines leading to nearby Paddington Station. The Westway had not yet been built and there were pleasant walks to the nearby canal basin, where she painted some views of the canal bridges. The area was popular with younger artists and writers but she remained loyal to Fitzrovia and Soho. She never really adjusted to the move from Howland Street and did little to make her new apartment habitable. Her wire-link bedstead was covered with old newspapers to keep in the heat and make it less uncomfortable and she hung her clothes on a piece of rope strung across the room. She had a rolltop desk but no comfortable chair or sofa. Her books were kept in a row on the mantelpiece and on a shelf above, which was propped up with a pile of Penguins. The threadbare carpet was badly stained with spilled drinks and was scattered with empty bottles, cigarette ash and opened books.

In the mid-twenties, she, Augustus John and Tommy Earp had been responsible for consciously making the Fitzroy Tavern on Charlotte Street a meeting place for artists in the spirit of a Paris café, and establishing a rival claim to that of Tambimuttu in having given the neighbourhood a name. With the war over, Nina still remained loyal to the Fitzroy, even though it was now better known as a pick up place for gay servicemen than for artists; an element of protection was afforded by its more celebrated regulars: the gay MP Tom Driberg, Hugh Gaitskell, Scotland Yard detectives Jack Capstick and Robert Fabian (‘Fabian of the Yard’), as well as the official hangman, Albert Pierrepoint. Most days Nina could be found at the bar and, if drinks were forthcoming, she would sometimes stay there all evening. If not, it was on to the Wheatsheaf, the French or the Swiss House on Old Compton Street.

There she would sit, perched on her stool, in her twenties coat with a furcollar, her beret cocked on the side of her head, often looking the worse for wear. In her autobiography Janey Ironside, professor of fashion at the Royal College of Art, described her as wearing ‘a very shabby navy suit with a rusty black shirt and grubby wrinkled cotton stockings. She was dirty, smelt of stale bar-rooms, and very pathetic.’ 7 Her conversation became increasingly abrupt and bizarre, her opening gambit inevitably: ‘Got any mun, deah?’ delivered in her cut-glass public school accent while rattling the tobacco tin in which her friends, and anyone else she could beg from, were expected to contribute to the price of the next double gin. When she did try and clean herself up the results were disastrous. ‘I took my grey dress to the dry cleaner’s and my dear, it just shrivelled up because of the gin soaked into it over the years. All they gave me back was a spoonful of dust.’ 8 She was only sixty-six when she died in 1956, falling on to the iron railings outside her flat in Paddington; almost certainly a suicide.

After six o’clock the northern reaches of Fitzrovia became depopulated as the nomadic tribes moved south in a tidal drift towards Soho and the pubs of Rathbone Place: the Wheatsheaf, the Marquis of Granby and the Bricklayer’s Arms. London boroughs had different opening times for their pubs. Through a quirk of the asinine licensing laws, the Fitzroy Tavern, the Wheatsheaf and the Bricklayer’s Arms all closed at 10.30 p.m. because they were in Holborn so that as closing time drew closer there was an exodus to the nearby Marquis of Granby which, being on the other side of Rathbone Place, was in Marylebone and stayed open until 11 p.m.. The more energetic hotfooted down Rathbone Place and across Oxford Street to Soho, where all the pubs stayed open until eleven. The nearest acceptable one was the Highlander (now inexplicably called the Nellie Dean), on Dean Street.

The Wheatsheaf on Rathbone Place is famous as the home from home of another fixture of that period, the writer Julian Maclaren-Ross as well as being one of the many watering holes frequented by Dylan Thomas. They were on friendly nodding acquaintance, having worked together writing film-scripts during the war, but both demanded their own courtiers and the loyalties and allegiances of the Wheatsheaf ’s patrons were much fought over so they never stood at the bar together. Maclaren-Ross had a fixed routine: from midday until closing time at 3 p.m. he drank at the Wheatsheaf, standing in his habitual place, propped against the far end of the bar near the fireplace. If he thought he would be late he tried to send someone to take up the position for him; it would have been intolerable to him to have to join the jostling crowd in the middle of the bar, where the service was not so good.

He stood beneath one of the tartans – not his own, as he often pointed out, (unnecessarily, as most people knew this was not his real name; he was born James Ross in South Norwood in 1912 – the Julian was an affectation, and was the name of a neighbour who assisted with his birth). 9 Dressed in his usual moth-eaten teddy-bear coat, dark sunglasses despite the pub gloom, a fresh pink carnation in his lapel, his black wavy hair swept back, waving a long cigarette holder housing a Royalty extra-large gold-tipped cigarette and sometimes gesticulating with his gold-topped malacca cane, Maclaren-Ross had successfully reinvented himself as a member of London high bohemia. Before the war, he had been a lowly door-to-door vacuum-cleaner salesman in Worthing, a tragedy retold in Of Love and Hunger (1947), but his stories of war-time conscription had been well received by both the critics and the public. Now he was a fixture of Fitzrovia, drinking beer with whisky chasers which he ordered using the Americanism ‘Scotch on the rocks’ that he had picked up from the popular films and thrillers he loved so much. When red wine once more became available after the war he switched to that.

After a late lunch at the Scala restaurant on Charlotte Street he would stroll around the bookshops on Charing Cross Road, where the only shop that sold Royalty cigarettes in Soho was located. He was back at the Wheatsheaf for opening time. He drank until 10.30 closing, then came a quick trot down Rathbone Place to the Highlander on Dean Street for a final half-hour drinking. He then walked back to Fitzrovia for supper and coffee at the Scala and home to wherever he was staying at the time: hotel, flat or park bench. Throughout all these hours, Maclaren-Ross would have been talking non-stop; virtually anyone would do as an audience. ‘At the sound of his booming voice, the habitués of the back tables, accustomed though they were to its nightly insistence, looked up in a dull horrified wonderment. There was no getting away from that voice,’ wrote Henry Cohen in Scamp.

Even at closing time, Maclaren-Ross would avoid going home, and would stop off for a nightcap with any of his long-suffering friends who would let him in. The writer Dan Davin and his wife were a frequent target and it never occurred to Maclaren-Ross that they might need to rise at a normal hour. He would settle down, drinking their whisky, an endless flow of anecdotes, some entertaining, others boring, and descriptions of movies recently and not so recently seen, emitting from his mouth until the bottle ran dry or his hosts nodded off to sleep in their armchairs. When he finally got home he would write, taking more amphetamines to keep him alert. In the middle of the night, using his gold Parker fountain pen, which he always referred to as ‘the hooded terror’, he would fill endless sheets of paper with his tiny meticulous handwriting, always writing two drafts, and correcting neither. They were always perfect, ready to be typeset.

Maclaren-Ross was known for his series of witty, cynical, largely autobiographical short stories collected as The Stuff to Give the Troops (1944), Better Than a Kick in the Pants (1945) and The Nine Men of Soho (1946). These days his reputation rests on his evocation of London’s wartime bohemian literary scene in Soho and Fitzrovia, Memoirs of the Forties (1965). Sadly he had only completed 60,000 of the projected 120,000 words when he died of a heart attack on 3 November 1965, but these chapters alone are regarded as masterful. The critic Elizabeth Wilson wrote: ‘For bohemians such as Maclaren-Ross, life was an absurdist drama, a black joke. This bleak, stiff-upper-lip stoicism was a rather British form of bohemianism, and Fitzrovia was a very British Bohemia.’ This was a view echoed by the critic V. S. Pritchett: ‘There is nothing else that more conveys the atmosphere of bohemian and fringe-literary London under the impact of war and its immediate hangover.’

Anthony Cronin worked for the literary magazine Time and Tide and employed Maclaren-Ross to write the occasional piece. Sometimes he would appear in the office quite broke, unable to write because ‘the hooded terror’ and his malacca cane, both heirlooms from his father, or so he claimed, were in pawn. His friend Anthony Powell, then on the Times Literary Supplement, gave him a regular supply of book reviews and ‘middles’ to write, which kept him going, and later, when Powell moved to Punch, he employed Maclaren-Ross to write literary parodies. Powell used Maclaren-Ross as X. Trapnell in A Dance to the Music of Time, now probably the main reason why people remember his name. Anthony Carson called him Winshaw in Carson Was Here and he appears in many memoirs of the period. Dan Davin wrote: ‘To be a friend of his meant not being a friend of a good many other people. He was arrogant and exacting in company. He did not like to take his turn in conversation; or rather, when he took his turn he did not let it go.’ 10

Maclaren-Ross’s snobbery and pretensions meant that the moment he had any money he would move into a suite at the Imperial or some other luxury hotel with no thought that in a week the money would run out and he would find himself on a park bench, a friend’s couch, or railway station concourse – he regarded Marylebone station waiting room as the most comfortable. He felt the same way about the newly established National Health System, preferring to owe money to a private doctor, and to have applied for unemployment money was not even considered. He was constantly on the move, pursued by irate landladies, hoteliers, bailiffs and tax collectors, rarely staying more than a week in a rented room before declaring that he had no money. It then took two weeks to legally evict him, during which time he sought his next accommodation. Some landladies fell for his hard-luck stories and extended him credit; one, who had finally to set the law on him, allowed him to run up an enormous rent arrears, £100 of it being paid off by the Royal Literary Fund, which paid the landlady directly knowing that she stood little chance of seeing it if they made the cheque out to Maclaren-Ross.

Despite his boorish and imperious manner, Maclaren-Ross could also be very funny. Wrey Gardiner, publisher of the Grey Walls Press, recalled:

Maclaren-Ross is tall, handsome and amusing. He came into the back of Subra’s bookshop the other day showing me round an imaginary exhibition of new painting. ‘Board with Nails,’ ‘Apotheosis’, ‘Coming of Spring’ – a bucket and brush, pointing all the time to real articles in the room. The painter, he said, was one Chrim. He will be immortal. 11

Though he regarded the fifties as ‘a decade which I could well have done without’, it did produce one of Maclaren-Ross’s more highly regarded books, The Weeping and the Laughter. But mostly it was a period spent in decline; he never stayed anywhere more than a few weeks before running out on the rent, dodging the bailiffs, living off a constant stream of advances for BBC radio scripts, talks, and parodies or articles and commissions that he rarely completed, all the while berating his long-suffering publishers and the producers at the BBC who had bent the rules for him.

The BBC Third Programme was the great unsung saviour of British bohemia. It came into existence in September 1946, directly after the war. Designed to propagate culture in its highest forms, it immediately became a major, and sometimes the only, source of funds for poets, playwrights, essayists, composers, short-story writers and public speakers. In his book In Anger the historian Robert Hewison identified a ‘BBC Bohemia’ but the majority of its inhabitants did not live in London; like an American ‘commuter campus’, it was a commuter bohemia. This was truly ‘London calling’. They included Hugh MacDiarmid, who lived in Scotland; Dylan Thomas, who spent most of his time in Wales when not touring America; W. H. Auden, who visited from New York; Laurie Lee, who lived in the Cotswolds; Robert Graves visiting from Majorca and Lawrence Durrell from Corfu; the travel writer Rose Macaulay; and a few London residents such as Muriel Spark, C. P. Snow and George Orwell. Hewison concluded: ‘The features department spent most of its time out of the department and in the pubs where virtually all BBC business was conducted in a miniature BBC bohemia.’ 12 For many of the Fitzrovia and Soho regulars this necessitated a change in drinking habits, though they only had to walk a few blocks to the pubs surrounding the BBC, where the commissioning took place.

Though the BBC Music Department was in Marylebone High Street, the new BBC Third Programme staff quickly adopted the George on the corner of Great Portland Street and Mortimer Street, which had long been the traditional watering hole of the classical music fraternity. BBC producers, writers and actors joined motor-car salesmen from their showrooms on Great Portland Street, and orchestral players from the nearby Queen’s Hall. Sir Henry Wood, musical director of the Queen’s Hall (and director of the Promenade concerts), is said to have named the George ‘The Gluepot’ because he could never get his players out of it. BBC classical music producer Humphrey Searle remembered it in his memoirs: ‘It was then a real rendezvous des artistes not usually overcrowded; many BBC programmes were discussed and settled within its walls.’ 13

This area was the centre for London’s classical music: visiting conductors traditionally stayed at the Langham Hotel – now the Langham Hilton, across from Broadcasting House – and before the war they walked across Portland Place to the Queen’s Hall to rehearse and perform. The Queen’s Hall had the finest acoustics in London. When it was bombed, the government promised it would be rebuilt but inevitably an ugly sixties hotel, the Saint George’s Hotel, went up in its place (though the view from its top-floor bar, ‘The Heights’, is superb). The much smaller Wigmore Hall, a few blocks away, was spared and is still in use. The George continued for many years as the meeting place for musicians and BBC producers but was taken over eventually by Regent Street Polytechnic students and by the sixties it had lost its charm.

For the written words the principal BBC Radio commissioning editors were the poet Louis MacNeice, John Arlott, later better known for his cricket commentaries, and the right-wing demagogue Roy Campbell. Writers and essayists began frequenting the pubs surrounding the BBC while waiting to rehearse or to broadcast, to meet producers and editors or simply to waylay producers in the hope of persuading them to give them work. As a consequence the Wheatsheaf, the Bricklayer’s Arms, the Highlander and the Marquis of Granby gradually fell from favour. The new pubs of choice became the Horse and Groom on Great Portland Street, nicknamed ‘The Whore’s Lament’, after the despair of the whores when the American servicemen left London at the end of the war (you have to drunkenly slur the pub’s name to reach this particular derivation), the George or Gluepot, the Dover Castle on Weymouth Mews on the way to Marylebone High Street, and the Stag’s Head on New Cavendish Street. In her memoirs, the BBC television presenter Joan Bakewell called the BBC commitment to the pub as a cultural institution ‘Dublinesque’: ‘the background to good, even inspirational talk, the setting in which to exchange and develop ideas, commission programmes, cast plays, transact business, pursue love affairs, avoid involvement in the bureaucracies that were even then shaping up inside the BBC.’ 14

For someone like Dylan Thomas, the Third Programme was a lifeline. His first solo broadcast for them was a reading from the work of Keats and in their first year he did fourteen more broadcasts for them as well as a further thirty-two for other BBC radio services such as the Eastern, and Light services. Dylan’s carefully enunciated rather upper-class tones quickly became well known to the educated British public. He was often employed to recite the work of other writers and he took a malicious delight in collecting other poets’ worst lines and using them in conversation. One evening in 1950, at the Stag’s Head, Dylan read aloud sentences and whole passages from George Barker’s The Dead Seagull which struck him as unbearably funny, as they did his audience. In 1953 for one of his many BBC broadcasts, Dylan was to read a poem by Edith Sitwell. That midday, after rehearsal, Dylan went to the Stag’s Head and did an imitation of Dame Edith bleating her poetry that had everyone in stitches.

Such was Dylan’s fame – he made over 200 broadcasts for the BBC and several television appearances, most of which the BBC didn’t bother to keep – that even a decade after Dylan’s death, it was still possible to run into people in the local pubs who would turn to you at the bar and begin: ‘When I was drinking with Dylan…’ Of course, some of the drinking stories are deservedly legendary, such as when, in October 1953, during a particularly drunken binge, he lost the only copy of the work by which he is best remembered, Under Milk Wood. His producer at the BBC, Douglas Cleverdon, traced his movements from bar to bar and recovered it from the Admiral Duncan pub on Old Compton Street.

Dan Davin, who spent a lot of time with Dylan in those days, remembered a day when Dylan met up with Henry Miller, who was visiting London:

They did a protracted round of the pubs and finished up at the little dairy on Rathbone Place which served sandwiches. The staff wore white and blue uniforms and the dairy was spotlessly clean but Henry Miller was not only drunk, but also short sighted, and got it into his head that Dylan had taken him to some particularly sophisticated brothel. Despite the waitresses protestations and Dylan’s wild attempts to set him straight, Miller refused to believe otherwise and it took a lot of Welsh tact to avoid the appearance of the police. 15

Davin has many insights into the man:

In adult life the drive towards the extreme, for he could do nothing by quarters and never drank a half, meant that when he was not at home writing poetry, one and the most intense pole of his being, he was in the pubs among the hard men. And hard men they were as long as they lasted: people like Roy Campbell, John Davenport, Louis MacNeice, Bertie Rodgers, Julian Maclaren-Ross, to name only those whose iron is now rusting in the grave. 16