5,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

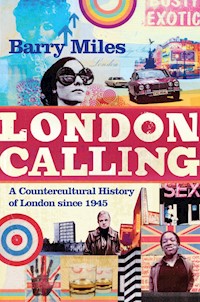

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

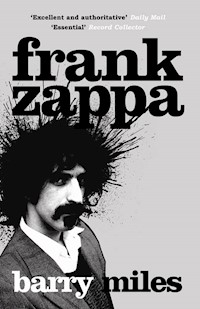

Barry Miles knew Frank Zappa intimately and was present at the recording of some of his most important albums. This sparkling biography brings the Zappa the musician and composer, Zappa the controversialist and Zappa the family man (despite his love of groupies, he was married for more than 30 years) together for the first time. Barry Miles' biography follows Zappa from his sickly Italian-American childhood in the 1940s (when his father, Frank senior, worked for the US military and was used to test the efficacy of new biological warfare agents) to his death from cancer in the 1990s. Miles shows how Zappa's goal had been to become a classical composer, until he realised that he would starve to death pursuing this ambition in post-war America. In an effort to make music people would actually listen to, in the mid-1960s he joined a noisy new band called 'The Mothers of Invention'. Before long, Zappa had taken over as singer, song writer and lead guitarist and together they exploded on to the San Francisco freak scene. Following the release of recordings such as Freak Out, Absolutely Free, We're Only In It For the Money and Hot Rats, Zappa's reputation in the United States and in Europe, especially the UK, Germany and Holland, took off. When the Berlin wall fell, Frank was surprised to learn that his extravagant music embodied sixties liberty for a generation of dissidents (including Vaclav Havel, who invited Zappa to be his minister for culture). Frank Zappa is an authoritative and hugely enjoyable portrait of a singular man and a vivid evocation of the West Coast scene.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Frank Zappa

Barry Miles is one of the most famous biographers of the sixties and seventies music scene. He is also one of the few writers to have been intimately acquainted with the rock stars whose lives he has chronicled. He knew Frank Zappa well and was present at many recording sessions, including the recording of Hot Rats.

Miles is the author of a number of seminal books on popular culture. His books include the authorised biography of Paul McCartney, Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now, Ginsberg: A Biography, Jack Kerouac: King of the Beats, In the Sixties, The Beat Hotel: Ginsberg, Burroughs and Corso in Paris, 1957–1963 and Hippie which was published in 2003.

‘Excellent… while it’s hard to warm to such a smartarse misanthrope, the book makes you realise what a uniquely talented musician Zappa was.’ Sunday Times

‘I am a big rock biography fan, and Frank Zappa was one of my heroes. The Barry Miles book made me look at him in an entirely different way. It is a serious work about a man who deserves to be treated seriously.’ Matthew Wright, Daily Express

‘Funny and revealing’ Evening Standard

‘Barry Miles’ prose style is lucid and unflustered – the perfect foil for the outlandish tales it comes to tell.’ Arena

First published in Great Britain in 2004by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

This paperback edition, with revisions and corrections,published by Atlantic Books in 2005

This digital edition published in Great Britain in 2014by Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Barry Miles 2004

The moral right of Barry Miles to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored ina retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781782396789

Designed by Richard Marston

Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondon W C1 N 3 J Z

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To David Walley, Urban Gwerder, Alain Dister and Mick Farren; pioneer Zappaists.

Contents

IllustrationsIntroduction1

Baltimore 2California 3Lancaster, CA 4Ontario, CA 5Cucamonga 6Studio Z 7The Strip 8Freak Out! 9Laurel Canyon10New York City11The Log Cabin12Bizarre/Straight13200 Motels14Waka/Jawaka15On the Road16Dr Zurkon’s Secret Lab in Happy Valley17Days on the Road18Orchestral Manoeuvres19Wives of Big Brother20One More Time for the World21On Out22Afterword

NotesBibliographyDiscographyFilms and BooksIndex

Illustrations

Frontispiece: Frank Zappa (Michael Ochs/Redferns)1

Baby Frank 2Frank and family 3Frank at graduation 41819 Bellevue Avenue, Echo Park 5The Canyon Store, Laurel Canyon Blvd 6Frank and his brothers 7Frank with his early band, the Black-Outs c. 1957 8Frank and Gail living in New York, 1968 9Frank with bull on the set for Head

10

Edgard Varèse11Composer Igor Stravinsky at rehearsal12Frank and his Mum13Frank and his Wife14Frank at home with his children15Frank and the Mothers at rehearsal16Frank conducts the LSO17Frank in Paris in the early seventies18Frank in London, 196719Frank with William Burroughs at the Nova Convention, New York, November 197820Frank reading from Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, New York City, November 197821Frank testifying at senate hearing22Frank Zappa as guitar hero

Introduction

In 1965 Cucamonga was just a village: a few streets clustered either side of Foothill Boulevard, historic Route 66, where it crossed Archibald Avenue about 75 miles east of Los Angeles. Around 7,000 people were scattered in the suburban desert sprawl that extended all the way to LA and connected the twin towns of Ontario-Upland to the west and San Bernardino to the east. Though this was the mid-sixties, the Cucamongans lived in a fifties time warp. It was a conservative, right-wing village and the male population wore short-sleeved white shirts and bow ties. Even a T-shirt was looked upon with suspicion. Cucamonga had a high school, a court house, a holy-roller church, a malt-shop and a recording studio, Studio Z, built by local boy Paul Buff, but now owned by 24-year-old Frank Zappa.

Business was slack: few Cucamongans wanted to record their bands, even at the very reasonable rate of $13.50 an hour, so Frank had to drive 75 miles to Sun Village in the High Mojave Desert every weekend where he earned $7 a night playing in a bar band. With him in the studio lived his 18-year-old girlfriend Lorraine Belcher and his high-school friend Jim ‘Motorhead’ Sherwood.

One of Zappa’s schemes was for a low budget science-fiction movie: Captain Beefheart Versus the Grunt People, starring Captain Beefheart (aka Don Vliet) and his parents. Zappa had bought $50-worth of stage flats that took up much of the back room of Studio Z, and had painted them with cartoon designs for a rocket ship and a mad scientist’s lab. Despite having no money, he had confidently announced a casting call for the movie. This drew the attention of the local police. Tipped-off by the Cucamonga police department, Detective Sgt Jim Willis from the San Bernardino sheriff’s office vice squad auditioned for the part of Senator Gurney (the ‘role of the asshole’, as Zappa put it) and was convinced he had uncovered a vice den.

To Sgt Willis, Studio Z looked like a bohemian ‘pad’. The walls were covered with newspaper clippings and memorabilia: a threat from the Department of Motor Vehicles to revoke Zappa’s driver’s licence, his divorce papers, a still of him on The Steve Allen Show, rejection letters from several music publishers, pop art collages and song lyrics. One was ‘The Streets of Fontana’, a parody of the folk music standard ‘The Streets of Laredo’, which Zappa used to sing with Ray Collins in the local clubs as a joke.

As I was out sweeping the streets of FontanaAs I was out sweeping Fontana one dayI spied in the gutter a mouldy bananaAnd with the peeling I started to play . . .

To Sgt Willis this was no joke. Zappa was clearly a threat to society. He ordered a surveillance team to drill a hole in the wall of the studio and for several weeks undercover police gathered evidence of subversive behaviour.

Then Sgt Willis visited the studio, this time in the guise of a used-car salesman. Attracted by the smart sign over the door (TV PICTURES), he explained that he and the boys were having a little party and wondered if Zappa could make him an ‘exciting film’ to suit the occasion. Zappa – who was living on peanut-butter sandwiches and instant mashed potatoes scrounged by Motorhead from the blood-donor centre – rapidly calculated that such a film would cost $300 to make. This was beyond the budget of the San Bernardino vice squad, so Zappa suggested that a tape-recording might suffice and would cost only $100.

Willis outlined all the things he would like to hear on the tape (including ‘oral copulation’) and Zappa said it would be ready the next day. Their conversation was relayed to a police tape recorder in a van parked across the street via a wrist-watch transmitter, like something out of a Dick Tracy cartoon.

That evening Zappa and Lorraine bounced around on the bed to make the springs squeak for a half-hour tape and added gasps, moans and what the police later described as ‘blue’ dialogue. There was no actual sex. Zappa edited out all the giggles and laughter and then, ever the professional, added a musical backing track. Sgt Willis showed up the next day and offered him $50.

Zappa complained that the deal was for $100 and refused to hand over the tape. At that moment the door burst open and two more sheriff’s detectives, plus another from the Ontario police department, rushed in, closely followed by a reporter from the Ontario-Upland Daily Report and a photographer. Zappa and Lorraine were arrested and handcuffed. Willis and his team searched the premises while the photographer’s flash bulbs went off. They seized every scrap of tape and strip of film in the studio and even took away Zappa’s 8mm projector as ‘evidence’.

Zappa and Lorraine were taken to the county jail and booked on suspicion of conspiracy to manufacture pornographic materials and sex perversion, both felonies.

It was front-page news in the Daily Report: under the heading 2 A GO-GO TO JAIL they breathlessly described how: ‘Vice squad investigators stilled the tape recorders of a free swinging a-Go-Go film and recording studio here Friday and arrested a self-styled movie producer and his buxom red-haired companion.’

Paul Buff loaned Zappa the money to get out on bail and Zappa got an advance on royalties from Art Laboe at Original Sound – who had a Mexican Number One with ‘Tijuana Surf’ by the Persuaders (Zappa had written the B-side: ‘Grunion Run’) – to have Lorraine released. They were arraigned the next week at the Cucamonga Justice Court across from Studio Z.

Before the trial, Zappa’s elderly, white-haired lawyer took him aside and asked: ‘How could you be such a fool to let this guy con you? I thought everybody knew Detective Willis. He’s the kind of guy who earns his living waiting around in public rest rooms to catch queers.’ Zappa had never heard of anything like it. The idea that there were people employed in the police department to do such things was a revelation.

He and Lorraine – now described as ‘a buxom red-haired girl of perfect physical dimensions’ by the increasingly excited Daily Report – appeared before the judge. At one point in the proceedings, he took them both, along with all the lawyers, into his private chambers to hear the ‘pornographic’ tape. It was so funny the judge started laughing, which outraged the prosecution. The case was being brought by a 26-year-old assistant district attorney who demanded that Zappa serve time for this piece of filth, ‘in the name of Justice!’

The case against Lorraine was dropped and Zappa was found guilty of a misdemeanour. He was given six months in jail, with all but ten days suspended, then put on three years probation. During this time he was not allowed to be in the company of a woman under 21 without a chapter one and, most importantly, must not violate any of California’s traffic laws.

The ten days in San Bernardino County Jail had a traumatic effect on Zappa, shocking him out of his innocence and creating the cynical, suspicious persona that defined him throughout his life.

Forty-four men were crammed together in Tank C in temperatures reaching 104 degrees. The lights were on all the time. There was one shower at the end of the cell block, but it was so grimy Zappa didn’t shave or shower at all. One morning he tipped his aluminium breakfast bowl over and at the bottom, stuck in the creamed-wheat, was a giant cockroach. He enclosed it in a letter to Motorhead’s mother, but the prison censor found it and threatened him with solitary confinement if he tried anything like that again. Zappa was powerless to fight back and sat there imagining monster guitar chords powerful enough to crack open the walls.

By the time he got out, he no longer believed anything the authorities had ever told him. Everything he had been taught at school about the American Way of Life was a lie. He would not be fooled again. He made sure that his pornographic tape was heard by everyone – he remade it time and time again, at least a couple of times on each album, rubbing it in the face of respectable society, making America see itself as it really was: phoney, mendacious, shallow and ugly.

1 Baltimore

Zappa means ‘hoe’ in Italian, symbol of the back-breaking toil of the Sicilian peasants who had to scratch a living from the dry stony ground. Frank Zappa’s father, Francis Vincent Zappa, was born on 7 May 1905 in Partinico, western Sicily, a small town of about 20,000 people. Partinico is twelve miles west of Palermo along a twisting mountain road. An area of astonishing beauty, with Greek temples, Roman bridges, Saracen mosques, Romanesque churches and cloistered monasteries set among olive groves and vineyards, it is also the Mafia heartland.

After the Second World War, the ‘Partinico Faction’ was the main supplier of heroin to members of the ‘Partnership’ – the ‘Partinico West’ families – who controlled Detroit, San Diego, Miami, Las Vegas, Tucson and other cities. Partinico is now dominated by five mafia families and is the capital of il triangolo d’oro di marijuana, the ‘golden triangle’ where cannabis grows in high-tech greenhouses among the vines. But when Francis Zappa was born, the mafia was only just coming into existence.

Family legend has it that he weighed an astonishing 18 lbs at birth. He was clearly healthy and was one of only four children to survive his mother’s 18 pregnancies. Francis had a brother, Cicero (later known as Joe) and twin sisters. Sicilian peasants lived in grinding poverty, with all its accompanying ill-health, disease and child mortality. They left in their thousands to find work in America, including Vincent and Rosa Zappa, Frank Zappa’s paternal grandparents. They arrived in Baltimore in 1908 on an immigrant boat with Francis and Cicero, their surviving children (sadly the twin girls died in a train crash).

The contrast could not have been greater: Partinico was a sleepy medieval town on the Mediterranean. Baltimore was a noisy Atlantic sea-port: a harbour filled with ships, a mixture of races and nationalities. It must have been a culture shock for Zappa’s grandparents. Vincent brought with him the peasant lifestyle of the old country. Frank Zappa: ‘What they said about my grandfather was that he never took a bath, used to drink a lot of wine and started every day with a full glass of Bromo Seltzer. And because he didn’t take a bath he wore a lot of clothes, and put cologne on. He had a terminal case of ring around the collar; one of those kind of fat Italian guys who would sit on the porch.’

The Zappas were hardworking immigrants determined to make a success and they worked all hours, eating pasta three times a day and saving their dollars and cents. They settled in a house on York Road in north Baltimore and Vincent used his savings to buy a barber-shop on the waterfront by the pier. Little Francis also did his bit. Zappa: ‘One of my father’s first jobs in life, he must have been about six [actually eight], was standing on a little wooden box in his father’s barber shop. He got paid a penny a day to put lather on the faces of sailors.’

The teenage Francis used his hairdressing skills to supplement his allowance while studying at Polytechnic High School. He was a good scholar and told Vincent that he wanted to go to college. This was the immigrant dream and his father dipped into his savings to give Francis $75 – a huge sum in those days. This, combined with his earnings as a bridge-player, enabled him to attend the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he gained a degree in History.

At college Francis was on the wrestling team and also played guitar in a musical trio. They stood under the windows of the dormitories and serenaded the co-eds with such catchy twenties ditties as ‘Pretty Little Red Wing, the Indian Maiden’ (a song with questionable lyrics). One of these girls was Nel Cheek. It was a college romance and Francis and Nel were soon married.

In November 1931 they had a daughter, Ann. Francis had graduated that summer and took a job teaching in Rose Hills, North Carolina, but there he encountered prejudice: they didn’t like Catholics and they didn’t like Italians. There had been mounting problems between Francis and Nel, but the final break came when he decided to take a job teaching in Baltimore. Nel did not want to leave her family and friends in Chapel Hill. They divorced and Ann stayed with her mother.

In 1935 Francis met Fifi Colimore, who liked him, but thought he was more suitable for her sister Rose Marie. She telephoned her at work and arranged for the three of them to meet for tea at the Italian consulate that evening, telling her sister she was going to meet a ‘nice man, a college graduate’. They got on well and Francis invited Rose Marie on a date. She met him at his college and watched from the back of the schoolroom while he taught a history class. Afterwards they had dinner in the college bookstore, which had a beer garden. But to Rose Marie’s Catholic family, the idea of her dating a divorced man with a child was completely unacceptable and they did everything they could to prevent it.

Frank Zappa’s mother, Rose Marie Colimore (known as Rosie), was born on 7 June 1912 in Baltimore, a first-generation American, the tenth in a family of eleven children. Her father, Charlie Colimore, came from Naples and her mother, Theresa, was born in Italy of French and Sicilian ancestry. They owned Little Charlie’s, a lunchroom at 122 Market Place, a block from the waterfront, as well as the adjacent confectionery store. The Colimores lived on Market Place, close to the store. Little Charlie’s was in the centre of Little Italy and had some pretty tough customers: sailors, stevedores and tug-men. Charlie and Theresa served the usual Neapolitan working-class fare: soup, pasta, fish, grilled or fried brains, fried calves’ liver, hog’s head, collard greens, sweet pastry or apple fritters and plenty of strong coffee.

Like many of the older immigrants, Theresa spoke little English. She would tell the young Frank Zappa stories in Italian and in his autobiography he remembered the tale of the mano pelusa – the hairy hand. ‘Mano pelusa! Vene qua!’ she would cry, running her fingers up his arm to scare him. Theresa was a strict Catholic and the church was the centre of her social life. Rosie remembered her childhood as ‘horrible’ – her mother never picked her up or held her. Perhaps Theresa was scared of getting too close to her children. It was an era of high infant mortality; the pain and anguish of a child’s death was too much to bear and she had borne many. Of Rosie’s siblings – Frank Zappa’s uncles and aunts – one sister died at birth; another, Margaret, died aged two of measles. Yet another, Rose, died shortly afterwards. Brother Louis got involved with a bad crowd and simply disappeared, aged 19, never to be seen again. It hurt to get too close.

Rosie attended the Catholic Seton High School and got on so well with the nuns that she almost joined the order. But her mother sobbed and protested until the idea was dropped. Theresa’s plan was for Rosie to remain a spinster and look after her in later life.

Rosie graduated from high school in 1931. She worked as a librarian and helped her mother at home before joining her older sister Mary as a typist at the French Tobacco Company in 1933. She made $17.50 a week – good money in those poverty-stricken days. It was while she was typing invoices and letters in French that she met Francis Zappa.

Theresa was appalled at the idea of her daughter marrying a divorced man, so Rosie and Francis met in secret. They dated for four years until one night, as they stood talking on the front porch, Theresa invited Francis in for the first time. She still wanted Rosie to look after her in old age, so only agreed to their marriage if they lived in the Colimore home. Rosie was 26 and legally independent, but she had been brought up in the strict Catholic ways of the old country and dared not defy her family. So Francis and Rosie were married on 11 June 1939 and moved in with Theresa and Charlie at 2019 Whittier Avenue, West Baltimore.

Frank Vincent Zappa was born on 21 December 1940 at Mercy Hospital in Baltimore. He almost didn’t make it. According to his Aunt Mary (Maria Cimino), who was there, the doctor had already delivered about nine babies that day and didn’t want to do any more, so he gave Rosie some kind of drug to retard her labour. ‘The baby was born breech and was going from bad to worse. At one point it looked as if they might lose both mother and child.’ Rosie had to have a blood transfusion. She was in labour for 36 hours and when Frank was finally pulled out by a nurse he was limp, the umbilical cord was wrapped around his neck and his skin was black. Francis was crying, convinced the boy would die.

But Frank recovered and was taken home (Aunt Mary remembered that he had ‘such beautiful eyelashes’). His parents only lived at Whittier Avenue for a short time. In 1941 Rosie’s father Charlie died after a long illness and Theresa sold the house. Francis was now teaching mathematics at Loyola Blakefield High School, a Jesuit preparatory school in suburban Towson, Maryland, so he moved his family to an apartment in the 4600 block of Park Heights Avenue in the north of Baltimore, an easy commute to the new school and closer to Rosie’s sister Mary. Zappa: ‘I remember it was one of those rowhouses. There was an alley in the back and down the alley used to come the knife-sharpener man – you know, a guy with the wheel. And everybody used to come down off their back porch to the alley to get their knives and scissors done.’

Frank’s younger brother Bobby was born on 28 August 1943. Theresa would care for him while Rosie and Aunt Mary took young Frank shopping with them on weekends at Hecht’s, Hutzler’s, Stewart’s and Hochschild Kohn, a quartet of elite department stores at the junction of Howard and Lexington Streets. He used to wear a sailor suit with a wooden whistle on a string around his neck. Aunt Mary remembered on one outing, when Frank was about three years old, he saw some nuns in the street and said: ‘Look at the lady penguins!’

After tea at Hutzler’s they would sometimes visit the Lexington Market, close to where Zappa’s grandfather Charlie had had his lunch-room. In the forties, hurdy-gurdy men could still be heard in all those East Coast cities with strong Italian neighbourhoods: New York, Baltimore, Philadelphia and Boston. A visit to Baltimore’s Little Italy at that time was like a trip to Italy itself.

Much of the Baltimore of the forties has been swept away by the switch to a service economy, the flight to the suburbs and by ‘urban renewal’. No more the screech of the street cars taking a corner on their iron rails, their web of overhead cables lacing the streets into long wide rooms or the steam whistles of the red tugboats of the Inner Harbour. Some fragments remain: the sound of wooden mallets breaking apart freshly steamed crabs, the polished marble steps of the distinctive Baltimore rowhouses, the leafy parks, the bay, the shot-tower – Zappa remembered being taken there as a child. It was the tallest structure in the United States until the Washington memorial was erected after the Civil War. Zappa also recalled visiting Haussner’s in East Baltimore, the enormous German restaurant with 112 items on its menu and every inch of wall space covered with paintings (though Zappa was too young to appreciate the naked ladies painted by Gérome and Alma-Tadema). Occasionally, the Zappas would also dine in Little Italy.

One of the most hated dishes of Zappa’s childhood was pasta with lentils. He claimed that his mother made enough to last all week and that after a few days in the icebox it would turn black. (Rosie hotly disputed this.) Either way, he had a lifelong aversion to pasta. The only Italian food he could bear to eat was pizza. He had an abhorrence of anything with garlic or onions in it, even the slightest trace, which meant he rarely ate in Italian restaurants.

As a child he enjoyed blueberry pie, fried oysters, fried eels and especially corn sandwiches (white bread and mashed potatoes with canned corn on top). As an adult he mostly survived on Hormel chilli straight from the can and ‘plump-when-you-cook-’em’ hot dogs cooked on the end of a fork over a gas ring. In a restaurant he would order hamburgers, simple steaks or chicken. He was plagued by digestive problems throughout his life.

The position of Italian-Americans in Baltimore was sometimes a difficult one. Prohibition had struck at the heart of Italian family life, where wine is an essential ingredient of a meal, both to drink and to cook with, causing people within the Italian community to import and sell it illegally. At the same time gangsters began to produce and sell alcohol and Italian-Americans were stigmatized by the actions of a few members of their community, mostly based in Chicago near the Canadian border, where much of the alcohol came from.

On a more positive note, in 1926 Baltimore elected the Sicilian Vincent Palmisano to the US Congress, the first Italian to take such high office. When the Second World War broke out, however, many Americans questioned the loyalty of Italian-Americans. Then Italy declared war against America and Italians became enemy aliens. Anyone who had supported Fascism and Mussolini was arrested by the FBI. As a result, Italian-Americans were especially conspicuous in the war effort, with patriotic fundraisers and large numbers of sons of immigrants enlisting to fight.

Francis Zappa’s loyalty was clearly unimpeachable, because he next took a job with the Navy in Opa-locka, Florida, working in ballistics research, calculating shell trajectories. Zappa’s father would be employed in the defence industry for the rest of his life. Rosie was reluctant to abandon her mother, but her duty was to be with her husband. Frank was a sickly child and his parents hoped the warmer climate would improve his health. They were right. The move to Florida had a tremendous impact: Frank’s condition improved almost overnight and he grew ‘about a foot’ in height.

Zappa told interviewer Rafael Alvarez: ‘All my life I had been seeing things in black and white while living in Maryland. And here I was down there and it was flowers, trees, it was great. It seemed like suddenly BOOM! Here’s Technicolor.’ Opa-locka is a northern suburb of Miami, which during the war housed a large military base. Much of the architecture has an Arabic flavour: houses with minarets and street names like Ahmad Street, Ali Baba Avenue, Sharazad Boulevard and even Sesame Street.

The Zappas lived in military housing for $75 a month and because they were in the Navy they didn’t experience the privations caused by gasoline and food rationing. Opa-locka is between Biscayne Gardens to the east and Miami Lakes to the west, and Zappa’s memories of Florida included watching out for alligators, because they sometimes ate children. He recalled a lot of mosquitoes and that if bread were left out overnight, it grew green hair. He was only four years old, but he also remembered air-raid drills: every once in a while they had to hide under the bed and turn out all the lights because ‘someone thought the Germans were coming’.

Then Rosie developed an abscessed tooth, which for some reason needed to be treated in Baltimore – perhaps through a family friend. However, Francis knew that once Rosie was back with her mother, she would never return, so he packed up the house and transferred to another military establishment at Edgewood, 21 miles north-east of Baltimore. ‘Even though I was sick all the time,’ says Zappa in his autobiography, ‘Edgewood was sort of fun.’ These years in small-town suburbia remained his principal memory of his childhood in Maryland.

His father worked as a meteorologist at the Edgewood Arsenal, headquarters of the Army Chemical Center. It was his job to discover ways of predicting the best delivery trajectories and weather conditions for gas warfare, a position that brought with it a top-secret military security clearance and Army housing on the camp. The Zappas moved into 15 Dexter Street in a now-demolished Army housing estate. Zappa had a clear memory of the place: ‘We were living in a house that was made out of cardboard . . . They were duplexes made out of clapboard . . . real flimsy stuff, real cheezoid.’

Winters on the Chesapeake Bay were very bad and the thin walls meant the house was always cold, despite a coal fire in the kitchen. In the mornings, before it was lit, Frank and Bobby would warm themselves by opening the door of the gas water heater to expose the flames. Around Christmas one year Bobby stood too close and the trapdoor flap on his pyjamas caught fire. His father beat out the flames with his bare hands, but neither of them were badly burned.

Zappa: ‘In those days they were making mustard gas at Edgewood and each member of the family had a gas mask hanging in the closet in case the tanks broke. That was really my main toy at the time. That was my space helmet. I decided to get a can opener and open it up. It satisfied my scientific curiosity, but it rendered the gas mask useless. My father was so upset when he found out . . . he said, “If the tanks break, who doesn’t get the mask?” It was Frankie up the creek. I was fascinated by [poison gas] . . . the idea that you could make a chemical and then all you had to do was smell it and you die . . . For years in grammar school every time we had to do a science report I would always do mine on what I knew about poison gas.’ Gas masks remained a source of interest and amusement in later life; for instance, the album Weasels Ripped My Flesh (1970) contains a track called ‘Prelude to the Afternoon of a Sexually Aroused Gas Mask’.

Francis brought home a lot of laboratory equipment – Florence flasks, beakers, vials and test tubes – for his sons to play with. He also brought home petri dishes full of mercury. Frank would pour the mercury on the floor and hit it with a hammer, making thousands of little blobs explode across the room. Eventually the floor of his bedroom was coated with a grey paste consisting of mercury mixed with dust balls. ‘My first interest was chemistry,’ said Zappa in 1981. ‘By the time I was six I could make gunpowder. By the time I was twelve I had had several explosive accidents. Somewhere around there I switched over to music. I gave up chemistry when I was fifteen. Chemical combinatorial theories persist however in the process of composition.’ In fact, although he knew how to make gunpowder at the age of six, he merely play-acted mixing the ingredients, dreaming of the day he would really cause an explosion.

When America entered the Second World War, the US Chemical Warfare Service had only one manufacturing installation to make conventional ammunition and toxic chemicals: Edgewood Arsenal, Maryland. Workers developed gas masks and protective clothing, trained Army and Navy personnel and tested chemical agent dispersal methods. The Army had been manufacturing and testing poison gas at Edgewood since 1917 and by the forties the site was contaminated by various toxic agents including sarin, mustard and phosgene.

Frank would often go with his father to catch catfish and crabs for the family table. Even today, Delaware, DC, and Maryland, the states surrounding the Chesapeake Bay, have the three highest rates of cancer in the United States. The bay is contaminated, but local people, especially those on low incomes, still catch and eat the toxic fish, crabs and snapping turtles in the bay.

Most of Zappa’s memories of living in Maryland are associated with ill health. He was prone to severe colds, sinus trouble and asthma. ‘In my earliest years my best friend was a vaporizer with the fucking snout blowing that steam in my face. I was sick all of the time.’ He was also inclined to earaches, which his parents treated with an Old World remedy: pouring hot olive oil into the ear. ‘Which hurts like a mother-fucker,’ said Zappa. As a young child he often had cotton wool hanging from his ears, yellow with olive oil. His sinus problems were treated by an Italian doctor using the latest technology: pellets of radium which he inserted into Frank’s sinus cavities on both sides with the aid of a long wire. The dangers of long-term exposure to low-grade radiation were unknown at the time.

Asthma, recurrent flu, earaches and sinus trouble are all symptoms of exposure to nitrogen or sulphur mustard gas. The fact that these ailments disappeared when the family moved to Florida and recurred when they returned to Maryland suggests that Zappa’s childhood illnesses were caused by living in a toxic environment. The toxicity of the Edgewood home was increased by a big bag of DDT powder that Zappa’s father brought home from the lab to kill bugs. This, he maintained, was so safe you could eat it. It was later banned as carcinogenic. Frank almost died at birth and was a sickly child; it is likely that the fact that he spent most of his life in the warm climate of Southern California, avoided drugs and rarely drank alcohol prevented a series of disabling illnesses.

Francis Zappa supplemented his income by volunteering for ‘patch tests’: the human testing of chemical agents. An unknown chemical or agent was spread on his skin and covered with a patch. He was not to scratch it or look under the patch, which he wore for several weeks at a time. Zappa remembered that his father came home each week with three or four patches on his arms or different parts of his body. For each patch he received $10. According to the Department of Veterans Affairs, an estimated 4,000 servicemen and civilian personnel participated in secret testing of nitrogen, sulphur mustard gas and lewisite at Edgewood and other test sites during the war. Later studies showed a relationship between exposure and the development of certain diseases for which veterans were entitled to financial compensation.

The Edgewood years were difficult ones for Frank and he spent much of his time alone in his sickbed. Rosie told Rafael Alvarez: ‘The whole time he had to stay in bed and rest he would have all his books on the bed. He was always creating something or inventing; he never liked sports. Every month something new would come for him in the mail.’ Frank later took to studying at the local library. He drew a lot (usually Indians and trains) and made puppets, sewing their clothes with a careful hand – a skill that proved useful later when he needed to repair torn clothing on the road.

At Edgewood Frank had three good friends: a Panamanian boy called Paul, whose grandmother used to cook them spinach omelettes; a crippled boy called Paddy McGrath, whose mother made them peanut butter sandwiches; and Leonard Allen, who shared Frank’s interest in chemistry. The two of them, in fact, succeeded in making gunpowder at Leonard’s house.

Frank, Leonard and their friends would ride their bicycles to the woods at the end of Dexter Road and climb trees. The road ended in a polluted creek where they caught crawdads. When it snowed, the children used flattened cardboard boxes to toboggan down the hill near the project. Frank also had his brother Bobby to play with, though sometimes sibling rivalry got the better of them. Francis was a strict father and Rosie tried not to let him know if the boys had been fighting.

Frank’s parents wanted their children to assimilate quickly and made a point of not teaching them Italian. They only used it at home to discuss something in private. Though Frank was just four years old when the war ended, people remembered that Italy had been America’s enemy and he came in for a certain amount of bullying. As he later observed: ‘World War Two was not a good time to be Italian-American in America.’

Frank was enrolled in Edgewood School on Cedar Drive. His teacher was Mary H. Spencer, who remembered him as ‘fairly mischievous, but he wasn’t naughty’. His parents were involved with the school and his father launched a campaign to have screens installed to prevent flies getting in to the classrooms. As a result of his efforts the cafeteria was eventually screened.

Frank seems to have been a popular child. His childhood sweetheart, Marlene Beck, then aged eight, remembered: ‘He was a cut-up . . . kind of like being the class clown. He was a very nice person, but he was always kind of strange.’ Zappa told Kurt Loder: ‘I first found out I could make people laugh when I was forced to give a little speech about ferns at a class in school. I don’t know what made them laugh, but they laughed, so I thought, “All right, not bad.” So I tried to develop it into a – I won’t say fern routine . . . ’

Zappa was about eleven at the time, as his third-grade teacher Cybil Gunther told Rafael Alvarez: ‘We had 40 or more in a class and kids could get lost in a crowd. Frank didn’t get lost in the crowd, but it wasn’t music he was into – he was big on drama. If for any reason I had to leave the room, I could turn to Frank and he would hold the class enthralled with something. I never did figure out what it was, but there was never any trouble with the class because Frank was doing something that never really made any sense to me. It was some sort of drama . . . some sort of cowboys and Indians. I don’t know that he liked the attention, but he liked what he was doing. I always had the feeling that he was doing it for himself. That it was rather immaterial to him whether people really sat there and listened. But he was happy in what he was doing.’

Zappa claimed his class act was a recreation of the scene in the 1949 Cecil B. DeMille movie Samson and Delilah, where Victor Mature pushed over the columns holding up the temple. Frank used cardboard tubes and rolls of linoleum as pillars.

Despite such efforts to be popular, there was one bully at school who kept beating him up. When Frank complained, his father told him he had to deal with it himself, or he would take care of Frank. The next day Frank waited for the bully and jumped on him, pummelling him with his fists. Bobby witnessed the attack and shot home to tell Rosie, who ran to the scene and pulled Frank off. Then they went home, put an ice-pack on Frank’s knuckles (and on Rosie’s forehead) and all ate a pot roast. The Principal telephoned and told Francis that his son was a brute and a troublemaker, but the next day Francis visited the school and gave the principal such an earful that she ran and hid in another room until he left.

Zappa frequently described his family as being poor, but ‘parsimonious’ seems a better word. In one interview he said that the idea of taking a family drive to see where their grandfather used to cut hair was regarded as ‘a rather large waste of money’ and he once complained: ‘I swear I don’t remember a single Christmas present.’ Yet childhood photographs show him in a sombrero, seated on a tricycle, and he mentions riding his bicycle when they lived in Edgewood, so he appears to have had the usual children’s toys. The Zappas also took the usual holidays, Rosie and the children spending summer at the seaside.

In his autobiography, Zappa recalls living in a boarding house in Atlantic City, where the owners’ Pomeranian used to eat grass and throw up something that resembled white meatballs. But rather than actually living there, as he suggests, the Zappas were undoubtedly spending the summer ‘down the ocean’, as they say in Baltimore (pronounced ‘downy eauchin’, according to Baltimore film-maker John Waters). It suggests they were never poor, as Zappa’s father told David Walley: ‘All my life I’ve made good money. It all went for food, clothing and environment. I’ve paid for everything I’ve wanted.’

Francis was fiercely protective of his family and not afraid to use his fists on anyone who criticized them or their background. In his autobiography, Zappa describes how Rosie had to dissuade his father from using his chrome .38 pistol to shoot his neighbour Archie Knight, who had been insufficiently respectful. Francis remained at heart a Sicilian.

Like all Catholic children, Zappa’s early memories were of kneeling a lot. He attended Mass with his family on Sundays and took Communion. He was confirmed and went to confession on a regular basis until he was 18. Zappa once said that his mother was from a ‘very strict religious family’, but he also told Peter Occhiogrosso: ‘I didn’t come from a family where everybody was kneeling and squirming all over the place in holy water fonts.’

In 1980 he told John Swenson: ‘The Baltimore catechism is one of the most absurd things in my recollection. It’s so vivid. That little blue and white cover and the stuff that was in there. I used to have to go to catechism class and the nuns would show you charts of Hell. They would flip the page back and show you the fire and monsters and shit in there that can happen to you if you do all this stuff. I’m going, “Hey, this is something. This is really exciting.” But you know, I’ve seen worse monsters in some of the audiences we’ve played for, and they were probably suffering more than the ones in that fake fire on the poster.’ There were also competitions. If you recited certain texts accurately, you were given a relic as a prize. Frank won one: a little card and a package with something sewn up inside it, which he was warned never to open.

Francis and Rosie wanted Frank to be an altar boy and sent him to parochial school, but he only lasted two weeks. He took one look at the nuns in their black vestments and starched white coifs like giant lilies, and revolted. After a nun hit him on the hand with a ruler he refused to go back. ‘I lasted a very short time,’ he said. ‘When the penguin came after me with a ruler I was out of there.’

Zappa was enrolled in the scapular: two small squares of brown woollen cloth, joined by tapes across the shoulders. He was never supposed to take it off, because the Virgin Mary had promised: ‘Whosoever dies wearing this scapular shall not suffer eternal fire . . .’ Zappa complained to Peter Occhiogrosso: ‘How can you do this? These strings are gonna rot from sweat, y’know? You go through life with brown felt stinky things with a picture sewn on one side and some strings that are full of sweat going over your shoulder. You’re supposed to wear this under your clothes for the rest of your life? I didn’t like that.’

There were other things he did not like. For instance, the way that kneeling to pray crinkled the toes of his shoes (‘You could spot a Catholic a mile away’); nor was he prepared to wear the brown corduroy trousers the church favoured. Nevertheless, the young Zappa accepted Catholicism as a significant element in his life and he was devout: ‘I just liked it. It felt right for me – I was that kind of kid. Some kids have that mystical bent; they can envision the whole aura of religion and it gets to them. That was my style at the time.’

Zappa’s illnesses continued and Francis decided they should settle permanently in a warmer climate. In 1951 he was offered a job at the Dugway Proving Ground in Utah, a division of the Chemical Warfare Service and closely connected with the Edgewood Arsenal. He came home with pictures and asked the family how they would like to live in the desert. ‘My father was so nostalgic for where he used to live in Sicily,’ said Zappa, ‘and the terrain looks like Arizona. It’s got that same kind of desert and mountains.’ Francis thought it would be a wonderful life, but his family did not. Zappa: ‘He showed us more of these cardboard houses . . . I was going, “No, I don’t want to go there.” But he thought it was nice.’ Under pressure from Rosie, Francis eventually decided against it. Instead he took a job at the Naval Post Graduate School in Monterey, California.

By this time, Zappa had two more siblings: a brother Carl (born 10 September 1948) and a sister Patrice, known as Candy (born 28 March 1951). According to Zappa’s Aunt Mary, Rosie told her the move to California was not permanent. She had missed her mother and sister while living in Florida and was saddened at the prospect of moving to the other coast. But theirs was an old-fashioned marriage and Francis made all the important family decisions.

The Navy shipped out their furniture and they prepared to leave. Francis bought one of the new Henry J two-door compacts introduced that year by Kaiser. It had a distinctive bullet-like shape, but there is nothing more uncomfortable than sitting in the back seat of a Henry J, as the three children discovered (just a few months old, Candy was on her mother’s lap). ‘That seat was a piece of wood with covering,’ said Zappa. ‘To spend 3,000 miles riding in the back of car like that with all your worldly possessions piled on top of you, that is not a terrific experience.’

They left in December 1951, taking the southern route. While driving through South Carolina they saw a black family working in a field. Francis stopped the car, went over to them and gave them every stitch of winter clothing they owned, telling them ‘Take it with our blessings.’ They were very grateful, but his family began to regret Francis’s altruism when they reached Monterey. In northern California it rained constantly and they no longer had any coats. Francis had assumed that all of California was like the Westerns he loved.

2 California

Francis taught metallurgy at the US Naval Post Graduate School on University Circle in Monterey and Zappa attended yet another new school. In his autobiography, he remembers that his father’s idea of a weekend outing was to pile into the Henry J and drive 18 miles inland to the lettuce-growing area around Salinas, where they would follow the farm trucks and pick up any lettuces that fell off. Francis was on a reasonable salary, so other factors must account for this level of penury. Possibly his self-published volume Chances: And How To Take Them (1966) provides us with a clue to their perpetual poverty.

It was dedicated, somewhat enigmatically, to his wife: ‘Whose kindness, patience and understanding has guided me through the many years of our married life. She knows not how to gamble, but she does know when and how to take a chance.’ The chapter headings are: (1) Probabilities, (2) Systems, (3) Keno, (4) The One-Armed Bandits, (5) Roulette, (6) Dice or Craps, (7) Poker, (8) Horse Racing and Sports Betting, (9) Black Jack or Baccarat, (10) Miscellaneous Dice and Card games, and (11) Mathematics of Possibilities. Virtually any one of these could lead to a college professor having to grub about in the gutter for damaged lettuces.

Zappa did his best to fit into his new school and overcame his self-consciousness and shyness by reprising his role as the class clown. He was an early developer and the first traces of his famous moustache were already visible on his upper lip: ‘I had a moustache when I was eleven, big pimples and I weighed about 180 pounds.’

It was not long before his ever-restless father upped and moved the family to Pacific Grove, a few miles west along the peninsula. A pretty little seaside town, ‘PG’ (as the locals call it) is famous for the thousands of Monarch butterflies that winter in its trees. It was an easy commute to Monterey and the quiet little town was better for the children.

Intrigued by his father’s profession, Frank longed for his own scientific apparatus. He particularly favoured the large-size Gilbert chemistry set that included the wherewithal to make tear-gas, but his parents demurred. Zappa told an interviewer in 1972: ‘My father wanted me to do something scientific and I was interested in chemistry, but they were frightened to get the proper equipment, because I was only interested in things that blew up.’ Ever resourceful, he experimented with household objects. He had some success with powdered ping-pong balls, which turned out to be ‘rewardingly explosive’. He also managed to produce a shower of little orange-yellow fireballs from the packing of some 50-calibre machine-gun bullets stolen from a garage across the street.

In his autobiography, under the heading ‘How I Almost Blew My Nuts Off’, Zappa fondly recalls one especially satisfying detonation. He gathered some used firework tubes from the gutters after the Fourth of July and primed them with his own special ping-pong ball dust. You could buy single-shot caps for toy guns and Zappa improved their performance by cutting away the extra paper. He sat on the dirt floor of his parents’ garage with the fireworks between his legs, pressing the trimmed single-shot caps into the tubes with a drumstick. He pressed too hard, igniting the charge. The resulting blast blew open the garage doors, left a crater in the floor and threw Zappa backwards several feet, though fortunately there was no anatomical damage.

The drumstick had come from Frank’s first instrument: a snare drum. In 1951 he joined the school band and became interested in music. Zappa: ‘I went to a summer school once when I was in Monterey and they had, like, basic training for kids who were going to be in the drum and bugle corps back in school. I remember the teacher’s name was Keith McKillip and he was the rudimental drummer of the area in Pacific Grove. And they had all these little kids about eleven or twelve years old lined up in this room. You didn’t have drums, you had these boards – not pads, but a plank laid across some chairs – and everybody stood in front of this plank and went rattlety-tat on it. I didn’t have an actual drum until I was 14 or 15 and all of my practising had been done in my bedroom on the top of this bureau – which happened to be a nice piece of furniture at one time, but some perverted Italian had painted it green and the top of it was all scabbed off from me beating it with the sticks. Finally my mother got me a drum and allowed me to practise out in the garage – just one snare drum.’

Zappa played his drum in the school orchestra and his first composition was a solo for snare drum entitled ‘Mice’. It apparently dates from the summer of 1953, when Frank was twelve. Zappa: ‘We had a year-end competition where you go out and play your little solo.’

He got his first record on his seventh birthday in 1947. It was ‘All I Want For Christmas Is My Two Front Teeth’ by Spike Jones and his City Slickers – a big Christmas hit that year. Frank liked it so much he wrote a fan letter to RCA Victor asking for a photograph. ‘I was expecting a photograph of Spike Jones in the mail,’ he told Charles Amirkhanian, ‘but instead, I got a photograph of a man named George Rock, who was the actual vocalist on that tune, and he looked like a master criminal. It was, like, a frightening thing to receive in the mail.’ In fact a photograph of Spike Jones, with his loud check suit and squashed-up, Mickey Rooney face, might have had a similar effect.

Zappa had a lot in common with Spike Jones: they were both perfectionists who only employed top-class musicians who were good sight readers and who were prepared to endure long rehearsals. Like Zappa’s groups, Jones’s musicians were expected to perform any crazy idea he might think up. The City Slickers were a comedy group and used a battery of unusual instruments to produce amusing sounds: washboards, pots and pans, doorbells, car-horns, cowbells and football rattles. Later he added pistols, guns and even a small cannon to his arsenal and employed a full-time arms roadie to look after them. As with Zappa’s later bands, many of Spike Jones’s players were fine jazz musicians and he always longed to produce more serious music. After the war, Jones formed a large dance band named the Other Orchestra to perform his more serious compositions, but it disbanded in 1946 after losing a lot of money (shades of Zappa’s 1988 touring band). ‘I used to love Spike Jones,’ said Zappa. ‘He had a lot of special instruments built to do all that stuff, like arrays of car-horns that you could honk that were in pitch. In the early sixties, when I moved to Los Angeles, they were having an auction of that equipment and I would have dearly loved to have bought it, but I had no money.’

In 1953 Zappa’s father, exasperated by the cold foggy climate of Northern California, took a job as a metallurgist with Convair in Claremont, about 30 miles east of LA, on the edge of the open desert he had always dreamed of. (Claremont was used by George Lucas as the location for American Graffiti.) It was another quiet suburban community. ‘Claremont’s nice,’ said Zappa. ‘It’s green. It’s got little old ladies running round in electric karts.’

Zappa transferred to Claremont High School. The other students were polite, reserved, white conservative types who wore the Californian equivalent of Ivy League clothes and studied hard to graduate in order to go to one of the local colleges. But before Zappa could really settle and make new friends, his father was off again, this time to El Cajon, an eastern suburb of San Diego.

El Cajon was not all that different from Claremont. Francis worked on the Atlas missile project and Frank moved to Grossmont High School. The California climate appeared to be doing him good. His illnesses had disappeared and at 13 he was taller than his father.

Grossmont High was not quite as white middle-class as Claremont, but the majority of the students aspired to San Diego State or Tempe, Arizona, and studied hard for their diplomas. It was a large school with a marching band, cheerleaders, a student government and all the elements of the archetypal American high school that were later celebrated by the Coasters, Chuck Berry, Eddie Cochran, the Beach Boys, Gene Vincent, Gary US Bonds, Dee Clark and scores more.

Frank took part in student activities. He had been interested in art from an early age and at Grossmont High he won a prize for designing a poster for Fire Prevention Week in a competition involving 30 schools. Zappa’s entry was headlined NO PICNIC and showed the faces of three disappointed looking children. Beneath it read: WHY? – NO WOODS. PREVENT FOREST FIRE.

Zappa was always very good at art, while his essays such as ‘50s Teenagers and 50s Rock’ for Evergreen Review show that he could have been a writer. His parents had no interest in music and there was no radio or television in the house, so the only music Zappa heard as a child came from outside: movie soundtracks, background music to soap operas, the big band music that was still popular in the early fifties, which he heard at friends’ houses. Zappa: ‘I think the first music I heard that I liked was Arab music and I don’t know where I ever ran into it, but I heard it someplace and that got me off right away.’

Then came the big breakthrough. Around the time of his thirteenth birthday, Frank was riding in the Henry J with his parents when ‘Gee’ by the Crows came on the radio, followed by the Velvets singing ‘I’. ‘It sounded fabulous,’ said Zappa. ‘My parents insisted it be dismissed from the radio, and I knew I was on to something . . .’ (Incidentally, ‘Gee’ by the Crows was also Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead’s first introduction to R&B, so it plays a key role in sixties American music.)

This was the music that moulded Zappa’s musical sensibility. R&B was his first and last love. ‘I think that one of my main influences, and probably one of the things that turned my ear around since the very beginning, is rhythm and blues,’ he said. ‘There’s just something about it. The earliest, most primitive rhythm and blues. All different styles from Delta stuff to Doo Wop vocal groups. I just loved it because of what was in it. Not because of the nostalgic aroma that goes with it, but musically, because of the sound of it, and because of the feelings that the performers had in that music at that time. It really said something to me. It’s something that I’ve always admired, a musical tradition that should be carried out into the future. I hate to see it go.’

In the summer of 1954 the Zappas acquired a Decca record player from the Smokey Rogers Music Store in El Cajon. It had a speaker on the bottom, raised on little triangular legs, and the pick-up arm needed a quarter balanced on it to ensure accurate tracking. Zappa remembered it as a ‘really ugly piece of audio gear’. The record player came with some free 78s, including a copy of ‘The Little Shoemaker’ by the Gaylords, which had entered the Top 10 in July 1954. Rosie liked to play it while she did the ironing.

Now that he had something to play music on, Zappa bought his first record: a 78 of ‘Riot In Cell Block Number 9’ by the Robins on the Spark label. (In fact, the A-side was ‘Wrap It Up’, but the B-side became a classic.) It was a prescient purchase by the 13-year-old Zappa, as the Robins had not yet had their big hit ‘Smokey Joe’s Café’, which prompted Carl Gardner and Bobby Nun to leave and form the Coasters. It showed Zappa’s ear for quality. This record also occasioned his first public appearance. Zappa: ‘The first thing I ever did in “show business” was to convince my little brother Carl to pretend he was my ventriloquist dummy, sit on my lap and lip-sync “Riot In Cell Block Number 9” by the Robins at the Los Angeles County Fair.’