22,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Robert Hale Non Fiction

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

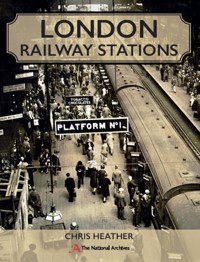

Built as part of the massive expansion of Great Britain's railway network during the nineteenth century, London's thirteen mainline railway stations are proud symbols of the nation's industrial and architectural heritage. Produced in association with The National Archives, and profusely illustrated with period photographs and diagrams, London Railway Stations tells the story of these iconic stations and of the people who created them and used them. Though built in an age of steam, smoke, gas lamps and horses, most retain features of their original design. This book will bring new light to these old buildings, and help you to see London's mainline stations through new eyes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 318

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Waterloo Station Junction COPY1409/219

First published in 2018 byChris Heather, an imprint ofThe Crowood Press Ltd,Ramsbury, Marlborough,Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2018

© Crown Copyright

Images reproduced by permission of The National Archives, LondonEngland 2018

The National Archives logo device is a trade mark of The National Archivesand is used under licence.

The National Archives logo © Crown Copyright 2018

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 2765 5

Disclaimer

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace and credit illustration copyright holders. If you own the copyright to an image appearing in this book and have not been credited, please contact the publisher, who will be pleased to add a credit in any future edition.

Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1 London Bridge, 1836

Chapter 2 Euston, 1837

Chapter 3 Fenchurch Street, 1840

Chapter 4 Waterloo, 1848

Chapter 5 King‘s Cross, 1852

Chapter 6 Paddington, 1854

Chapter 7 Victoria, 1860

Chapter 8 Charing Cross, 1864

Chapter 9 Cannon Street, 1866

Chapter 10 St Pancras, 1868

Chapter 11 Liverpool Street, 1874

Chapter 12 Blackfriars, 1886

Chapter 13 Marylebone, 1899

Index

Introduction

WHEN THE RAILWAYS BEGAN TO BE built in Britain over 180 years ago, London was already the largest city in the world. With a population of around two million people in 1830, London was not only a capital city: it was the hub of the British Empire, soon to become the largest empire the world had ever seen. No wonder, then, that London became a magnet for business, trade, work and entrepreneurs. A key aspect to this development was the coming of the railway, a transport system that changed the face of London forever.

Nearly three billion rail journeys are undertaken each year in the UK, and nine of the ten busiest stations are in London. Waterloo Station alone deals with a quarter of a million passengers each day. There are thirteen mainline termini in London, more than in any other capital city. Moscow, for example, has only nine mainline stations, while the French capital, Paris, a city of similar age and status to London, has a mere seven. There are two main reasons why London has so many stations: firstly, Britain was the first country to develop a railway system at a time of huge industrialization, when goods and people needed to move around the country, and businessmen saw opportunities to make large profits. London was therefore ahead of the game.

Secondly, the British Government saw no need to provide an overall plan for the railway network across the country, or in the capital. It was left to individual companies to propose new railway lines, seek parliamentary approval, and raise enough capital to get started. This led to huge competition and rivalry between the various railway companies, each one striving to make money by choosing a different ‘market’, whether it was holiday traffic to Devon, the movement of beer from Burton-on-Trent, daily commuters to London, or collecting goods arriving at the Thames docks. This freedom was fertile ground for engineers and architects to come up with unique buildings and structures, many of which can still be seen today.

The laissez-faire approach to transport infrastructure also led to the duplication of lines, the unnecessary embellishment of buildings, the demolition of housing, vast over-expenditure by companies, and many other issues, which can be seen as good or bad depending on one’s perspective. Nevertheless, this is how the railways evolved, and how they came to influence the layout of the capital city we know today.

The story of London’s stations is one of co-operation and competition, personal ambition and corporate determination. It includes instances of innovative design, technological invention, devotion to service, and triumph over bureaucracy and difficult physical terrain. All thirteen mainline stations were built during a sixty-four-year period, starting with London Bridge Station, which opened in 1836, and ending with Marylebone, which was the last to open in 1899. Each one has its own personality and its own charms and idiosyncrasies. These were determined by location, the functions the stations were designed to perform, the status of the architect, the pride of the railway company, and of course the amount of money available at the time.

These buildings were new inventions in themselves. No one had created a large railway terminus in a capital city before, and nobody knew how they should look or what they should include, and although mistakes were sometimes made, architects had a free rein to create buildings that would be both functional and impressive. Often they would borrow from the grand styles of classical Greek, Roman and Gothic architecture, and this theme would be extended to the associated railway hotel, many of which are today some of the most richly decorated and luxurious hotels in London. As well as hotels, each station could have a retinue of support buildings: offices, stables, goods yards, signal boxes, bridges, viaducts and railway lines, which provided succour to new urban development along their routes, with housing and businesses contributing to the suburbia that would eventually become Greater London.

This book tells the story of each of these stations, how they came to be positioned where they are, who designed them, and what happened to them over time. Through these pages we meet some of the people who built them, worked in them, passed through them as travellers, and even died in them. A wide variety of human activity can be seen here, each anecdote contributing to the narrative of these vital structures that are so familiar to us, and yet which come from another age – an age of steam, smoke, gas lamps and horses. This was an age when a rented brass foot warmer was the height of luxury, and when hailing a cab from the station meant travelling by two wheels and four hooves.

These stations have survived many changes over the years, some more sympathetic than others, but most of them include preserved examples of their original design, bearing testament to the perception, skill, enthusiasm and foresightedness of their Victorian creators. I would encourage you to visit them, to take in the atmosphere and to spot some of the original features, since all can be reached in a couple of hours quite easily from the Circle Line on the Underground. And I hope this book will bring new light to what may be for you very familiar buildings, and help you to see London’s mainline stations through new eyes.

Chris Heather, 2018

Chapter 1

LONDON BRIDGE, 1836

THE STORY OF LONDON BRIDGE STATION begins with Lieutenant-Colonel George Thomas Landmann, your archetypal Victorian adventurer. A man with an entrepreneurial spirit, he played his part in literally building parts of the British Empire. The son of a German professor, he was born in the grounds of the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, in 1780. He lived a full and varied life, and his colourful escapades, and his inventiveness and ability to get things done, helped to change the face of London.

Landmann was educated at the Royal Military Academy from the age of fourteen, and went on to join the Royal Engineers two years later in 1795. He was posted to Canada, where he built fortifications and a canal. It is said that he once came across a native Indian tribe who were about to torture and burn a woman and her child from another tribe. Landmann stepped in and bought them for six bottles of rum, and returned them to their own people, receiving valuable animal skins by way of acknowledgement. He later moved on to build bridges in Portugal, and in Spain he commanded troops, and built fortifications as part of the defence of Cadiz. The King of Spain thanked him personally for helping to quell an uprising, and he served in several battles and sieges before returning to England because of ill health in 1812.

He continued to serve in the military in Ireland before retiring from the Army in Yorkshire in 1824. Once retired he embarked on a career in civil engineering, becoming a member of the Institution of Civil Engineers, and was appointed engineer to the Preston and Wyre Railway and Harbour Company, helping to build docks at Fleetwood in Lancashire. It was while working on railway projects that he had the idea of building a railway to the City of London.

In October 1831 Landmann and his colleague George Walter, who had previously tried and failed to launch a railway company called The Southampton and London Railway Dock Company, decided to form a new railway company called the London and Greenwich Railway (L&GR). The line would be a short one of just under four miles, running from Greenwich up towards the City, terminating just to the south-east of London Bridge. London Bridge itself was fairly new at this time, having been completed in 1831, and built by civil engineer John Rennie. This was the bridge that was dismantled and replaced in 1971, having been bought by Robert P. McCulloch, an American oil tycoon, who rebuilt the structure at Lake Havasu in Arizona, USA. It is often said that McCulloch thought he was buying London’s iconic Tower Bridge, but this is just an urban myth.

A Viaduct for the L&GR

A shareholder’s prospectus for the L&GR was printed in May 1833, listing the company directors, auditors and bankers, with George Landmann proudly highlighted as ‘Engineer to the Company’. In it the company acknowledge that constructing a rapid means of conveyance into a central part of ‘this great Metropolis presents difficulties of no ordinary magnitude’, due to the prospect of interfering with the traffic. To solve this problem they announce that ‘This Railway is therefore to be constructed on Arches, and in such a manner that Passengers and Carriages may pass along the Streets which the Line will cross, without being obstructed.’ Construction of the track was indeed difficult because of the number of streets already built along the line of the proposed track. Landmann could have created a line with numerous level crossings, but this would have meant slower trains and continual obstruction to road traffic, so an elevated viaduct, high above the streets, was the innovative answer.

This new line would be in direct competition with boat traffic on the Thames, the number of boat passengers up and down the Thames during 1831 being estimated at 400,000. The number of people travelling between Greenwich and the city was about 2,000 per day, and then there were horsedrawn coaches as well, so the L&GR needed to provide fast and reliable transport in order to compete. The L&GR would be a raised railway line supported by a series of 878 brick arches, which Landmann hoped to rent out as stables, shops, workshops and even dwellings. A couple of two-storey show homes were built inside two of the arches, each with six rooms, and two windows on the first floor and a window and door at ground level. However, these arches were not watertight, and the continual noise of the trains made them unsuitable as homes. Nevertheless, the archways did prove popular with light engineering companies and for use as lock-up garages. One arch halfway along the viaduct was converted into a pub, known as the Halfway House Tavern, later the Railway Tavern; it survived from the 1850s until 1967.

To provide for large users of the arches, small connecting transverse doorways were built into the walls of each arch, and these could either be left open or bricked up as required. The problems with damp were eventually solved by the application of a further layer of concrete and asphalt, and early on there were even plans to provide the arches with heating and lighting, although this never came to pass.

The land over which the viaduct was built was quite soft and peaty, and the 400 navvies used to build the structure were forced to dig foundation pits up to twenty-four feet deep, so as to provide enough stability to support the viaduct. Landmann was also obliged to use concrete reinforced foundations, and iron ties to stop the piers spreading and collapsing. It took five years to build the viaduct using sixty million bricks, all made in Sittingbourne, Kent, and transported to the site by barge along the Thames. The cost of the structure was £733,000 (almost double the original estimate of £400,000), much of which was spent on buying the necessary land and property.

Parapet walls were built along the sides of the viaduct, 1.3 metres high to prevent walkers, and any trains that might derail, from leaving the viaduct. The train carriages were specially designed to have a low centre of gravity to give them additional stability along the viaduct. This was the work of George Walter, secretary of the L&GR and founder of the Railway Magazine, who turned the usual carriage frame upside down so that the axles were above it rather than underneath it. The heavy frame, now running only four inches above the rails, meant that the vehicles were less likely to sway and rock along the track. The passenger compartments were then raised on blocks up to their previous level, some twenty-five inches above the rails, and this design proved to be very successful in providing stability and avoiding derailments.

Chronological plan showing the development of the London & Greenwich Railway and associated line. ZSPC11/345

Next to the track, along the top of the viaduct, was a ‘pedestrian boulevard’ along which members of the public could walk at the cost of a penny a time, allowing them to enjoy views across London and the nearby countryside, and to experience the railway close at hand. This walkway was soon converted to an additional train line when the profitability of further train lines was realized. The track itself was laid initially on to concrete sleepers, but these proved to be too rigid on top of the solid viaduct, and caused problems through noise, vibration and broken wheel axles, so they were eventually replaced by wooden sleepers on a bed of gravel ballast, which provided a little more flexibility.

Another feature of the original plans for the Greenwich Railway was a roadway and gravel path, planted with trees, which was to extend twenty-four feet on each side of the viaduct from end to end. This road was designed to provide access to the archways along the viaduct, and to become a great thoroughfare in itself, along which families and respectable people could promenade in the shade of trees, protected by railway company policemen, and all for the modest cost of 1d per visit. Parts of the road were constructed, but it was not well maintained and soon became rough tracks of muddy ruts and puddles in wet weather. Revenue was collected for a few years (£500 in 1839) but the widening of the viaduct on both sides meant that the avenue was no longer viable, and the tolls were discontinued around 1845.

The whole project provided an early template for many later railway viaducts constructed across London and other cities. Technically speaking the structure is actually nineteen separate viaducts, which are linked together by twenty-seven road bridges. Even today it is the longest run of arches in Britain, and one of the oldest railway viaducts in the world. The original viaduct was widened in places in the 1840s and 1850s along both its north and south sides.

On 9 June 1835 the engine Royal William, weighing fourteen tons, carrying several passengers and her tender primed with water and coal, completed a trial run of one mile in four minutes near Blue Anchor Road, watched by company directors and shareholders. A glass of water filled to the brim was placed on one of the stone sleepers, and not a drop was spilled as the engine passed along. More trials took place with full-length trains this time; then on 12 November a carriage came off the tracks, and although it ran a number of yards, no one was injured. Landmann, ever the optimist, congratulated the shareholders on the derailment as it showed how safe the viaduct was even when accidents occurred. Royal William was Engine No. 1 of the L&GR, built by Tayleur and Co. at the Vulcan Foundry, and was the first steam engine ever to provide a passenger service in London.

The Sceptics

Not everyone was in favour of the new railway, most notably George Shillibeer, the famous pioneer horse bus proprietor, who had set up a business running twenty omnibuses linking London, Greenwich and Woolwich in 1834. He promoted the idea that train travel was dangerous, and by contrast his buses would neither blow up nor explode ‘like mines’, that no one need fear travelling in them. He said that the railroad was not worth investing in as it would be put out of business by horse buses. Unfortunately for him he was proved wrong when his buses were all seized by the Stamp Office when he fell into arrears with his payments shortly after the new railway opened.

Similar scepticism was evident in the comments of the Quarterly Review publication for March 1835, when speeds of eighteen miles per hour were expected of the new railway: ‘We should as soon expect the people of Woolwich to be fired off from one of Congreve’s rockets as trust themselves to such a machine going at such a rate.’

The Opening of the L&GR

The first section of the London and Greenwich Railway line opened to the public on 8 February 1836, running from Deptford to Spar Road, near the junction with Rouel Road, and such was the excitement generated by the new service that it managed to carry 13,000 passengers on its first day alone. This effectively makes Spar Road Station London’s first ever railway terminus, although it was little more than a couple of wooden platforms atop the viaduct, and a rickety wooden staircase up from ground level. The line soon reached London Bridge Station, which opened on 14 December 1836, after several postponements. Formal invitation cards for the opening ceremony had been printed for Tuesday 1 November, but the event was put off and the cards were over-printed with 14 December.

The London and Greenwich Railway and associated lines. RAIL1075/146

The opening ceremony was a grand occasion, where four trains made their way down to Deptford at a steady twenty miles per hour, carrying the Right Honourable Thomas Kelly, Lord Mayor, and various city dignitaries in the first train, while the band of the Scots Guards played them off. A short distance outside the station the Mayor’s train halted while the three other trains passed by on the other line in procession. Then the three trains stopped while the Mayor’s train passed by to applause, leading the way to Deptford, where the band of the Coldstream Guards welcomed them playing both ‘popular and national music’.

Whilst at Deptford the Lord Mayor inspected the company works underneath the station, before walking from the High Street to the Ravensbourne River where he inspected the bridge. He then received a deputation from the inhabitants of Deptford, gave a speech, and then returned to London by train, this time reaching speeds of up to thirty miles per hour. Around 2,000 people attended the ceremony, with 500 enjoying a formal dinner afterwards, where they celebrated the railways reaching the capital.

London’s First Passenger Railway Terminus

London Bridge Station can therefore be said to be London’s first passenger railway terminus, beating the London and Birmingham Railway’s Euston Station, which opened on 20 July 1837. The actual station building, however, was very basic. On the south side of the London end of the viaduct was a simple three-storey building which housed the booking office and the company offices. The rest of the station simply comprised two platforms serving three railway tracks. There were no waiting rooms and no roof or train shed of any kind. Passengers would climb steps, or use a ramp to make it up to platform level, where they would wait in all weathers for their train to depart.

Houses under the arches of the railway approach to London Bridge Station. ZSPC11/345

First Customer, the L&CR

The L&GR did not set out to make a statement with their station, as other railway companies would try to do in the coming years. Instead their plan was to stake a claim to a convenient access point to London, and then make their fortune by charging other railway companies for access to it. From the outset the directors planned for the potential continuation of the line from Greenwich down into Kent and Sussex, and even to Dover for connection with the continent by boat. By keeping the station simple they could save on initial outlay, yet at the same time they owned enough land around the terminus to expand at a later date once they had become fully established. Their first customer was the London and Croydon Railway Company (L&CR), which used the L&GR line to build their own terminus to the north of the L&GR station, opening on 5 June 1839.

Further back along the line the L&CR built their own viaduct to take their trains south, branching out from the original arches at a junction near Corbett’s Lane, and forming the world’s first railway junction. At the point where the tracks diverged a ‘policeman’, or signalman, was positioned in a wooden tower so as to control trains moving between the two lines. At night time signalling in the form of red and white lights was introduced, and the tower therefore became known as the Corbett’s Lane Lighthouse. This was in effect the world’s first signal box.

Water Refuelling System

Engines leaving London Bridge Station would always run ‘backwards’, with their tender or bunker first. This was because there was no water crane at London Bridge, and water was taken on board at the other end of the line at Greenwich, where, on arrival, the carriages would be uncoupled and the engine would continue beyond the station a little way on to a turntable, next to which the water crane was located. The turntable was basically a short section of track that could revolve, lining up with a number of different lines, above a shallow circular pit. Once refuelled with water the turntable would rotate and direct the engine on to the appropriate line for the return journey to London. The system worked well, apart from on one occasion in 1861 when a driver backed his engine on to the turntable, not realizing that the track was still aligned with the tracks for London. His tender ended up in the pit, thus blocking the only water source for the whole of the line.

New Lines for the SER and the L&BR

The South Eastern Railway and the London and Brighton Railway also began to run over the London and Croydon tracks and into London Bridge Station, joining the original London and Greenwich tracks at Corbett’s Lane, Deptford. Due to the increase in traffic the viaduct was widened between 1840 and 1842 to four lines from Corbett’s Lane to London Bridge. The new lines were added along the south side of the viaduct, although they were intended for use by the Croydon, Brighton and SER trains, whose station was on the northern side of the L&GR station. This would have required a complicated points system, and the danger of trains crossing each other’s tracks, so the directors of all the companies concerned agreed to swap stations – the L&GR would move into the new L&CR station, while the remaining companies would take the original station, which they promptly decided to demolish in order to build a bigger one.

A New Joint Station

By 1844 a new, much larger, Italian palazzo-style joint station had been built, designed by Lewis Cubitt and Henry Roberts, and large enough to cope with the additional traffic from the SER and the L&BR. Early drawings of the proposed station show it as having an ornate bell tower at one end, although in actual fact the tower was never built and the station was never finished.

When the service began the company provided carriages for three classes of passenger. First class compartments had horse-hair cushions and sloping seats with leather inserts, while second class coaches had narrow, upright seats. Accommodation for third class passengers was very basic, being open wagons without seats, known as ‘standipedes’ or ‘stanups’. Complaints regarding such poor accommodation were brushed aside by the directors, who considered there was ‘no justification for the murmur. If the people would insist on travelling at so cheap a rate, it was only reasonable that they should pay the penalty in a certain amount of discomfort!’ The third class option had been withdrawn by 1842 when the secretary of the L&GR, a Mr Akerman, replied to a government survey regarding third class passengers – his letter provides a useful insight to the accommodation provided on their trains:

The trains on this line run every quarter of an hour each way. There are no third class, but only first and second class passengers. The carriages on this Railway are similar to those of the Blackwall, the second class passengers occupying the end division and the first class the middle. The end divisions hold about 20 second class passengers and are 7 feet wide by 5 feet long and 7 feet from the floor to the roof. They are without seats.

The two first class divisions are 7 feet wide by 5 feet long, and hold eight passengers. All the above carriages are provided with undersprings, draw-springs and buffing apparatus, and are mounted on six wheels.

The L&GR were charging the other railway companies high fees for the use of their facilities, 3d per passenger, and so the SER obtained permission to build their own terminus at Bricklayers Arms, also opening in 1844. This meant that only the L&GR and L&BR were left using London Bridge Station. In 1845 the L&GR relented and reduced their fees to 1¼d per passenger, and leased the whole of the line to the SER for a term of 999 years. The SER now controlled the approach to London Bridge Station.

Early sketch of the advertisement ‘Trains to London Bridge every fifteen minutes’. ZSPC11/345

London Bridge Station Divided

In 1846 the L&CR merged with the L&BR and others to form the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LBSCR), which used the joint station until 1849 when it was knocked down in order to build a larger station. Meanwhile the SER took over the L&GR station on the northern side of the site, which they rebuilt between 1847 and 1850 to a design by Samuel Beazley, incorporating a solid wall between the two stations, emphasizing the division of the station into two separate halves. Their Bricklayers Arms station was then converted into a goods depot, then a parcel depot in 1969, and in 1981 the line was closed.

The LBSCR build the Terminus Hotel in 1861, alongside the station. It was leased to a private hotel company, but was not very popular, being on the south side of the river, and in 1892 it was taken back by the railway company and turned into office accommodation. It was built on land previously owned by St Thomas’s Hospital, and occupied by low grade housing. The architect of the hotel was Henry Currey, one-time colleague of William Cubitt and designer of St Thomas’s Hospital. The building was constructed from white bricks with Portland stone dressings. There were 250 rooms, and the hotel cost £111,000 to build. Sadly, the building was badly damaged by bombing in 1941 and was demolished thereafter.

Provision of Services

London Bridge Station continued to evolve in a divided way, as two separate stations, run by different companies, each with their own style and agenda, the SER controlling the northern side, and the newly formed London, Brighton and South Coast Railway managing the southern half. This meant that rules and procedures in place on one side of the station would not apply in the other half. For example, in 1888 the SER entered into an agreement with the London Road Car Company for them to provide a horse-drawn omnibus service to pick up and deliver passengers to the station. This gave the car company permission to traverse the SER-owned approaches to the station, but not those owned by the LBSCR, for which they would pay the SER three shillings per week for each omnibus used. By 1913 the service had been replaced or supplemented by a Mr Frederick Tindle, who used his single horse-drawn omnibus to provide a similar service, paying the SER five shillings per week for the privilege. However, his omnibus was specifically forbidden to loiter on the approach, and his servants were not permitted to tout for business.

Some services did end up the same in both halves of the station, although this was more by luck than through planning. Mr John Perrett was already running the refreshment rooms in the SER side of the station when in November 1862 he answered an advertisement in The Times newspaper for someone to run the refreshment room in the LBSCR side. He wrote three letters to the company explaining that he was ideally situated to provide the service, and was willing to pay £1,000 per year in rental, or 5 per cent more than anyone else submitting a tender. The LBSCR, perhaps realizing that Mr Perrett was perfectly positioned to provide the service, but also that he was so keen to strike a deal that he could be persuaded to pay a little more, offered him a contract at £1,400 per year for the following seven years. Mr Perrett accepted the offer on 3 December, and passengers could therefore enjoy the same standard of tea and cake in whichever half of the station they found themselves.

Increasing Traffic Brings Problems

Passenger numbers grew rapidly in the next few years, and both halves of the station undertook changes to deal with increased traffic. The SER side converted into a through station, with new tracks out to Charing Cross, while the LBSCR side grew in terms of additional, longer platforms. The viaduct into the station was widened to carry eleven tracks, and the LBSCR introduced electric motive power via an overhead cable system for some services. This was replaced between 1926 and 1928 by the third rail system of electric power, overseen by the new Southern Railway Company formed by the amalgamation of the railways companies of southern England in 1923. So finally, after eighty-four years, the two halves of London Bridge Station were united and run as a single entity.

London Bridge Station had begun to get a reputation for being difficult to navigate – confusing for passengers and for being overcrowded. The decisions of the various rival railway companies in the mid-1800s had badly affected the design of the station, leaving lasting repercussions for passengers, making it one of the most difficult London stations to navigate. However, in 1928 a footbridge was installed joining the two halves of the station for the first time, and allowing passengers to make connections without having to leave one half of the station to walk round to the other half. This was a great improvement considering the station dealt with around a quarter of a million passengers each day. However, an article in the Railway Magazine published in February 1937 shows that the problems were still present:

Perhaps as a result of its promiscuous begetting, London Bridge station has not the most efficient layout in the world. This is noticeable particularly during the evening rush hour when in the Central section passengers stream in from a dozen different entrances, and if their destinations should take them over to platforms 16–22 they may become entangled with a succession of newspaper vehicles, post office vans, parcel vans and packages, and also with a crossflow of passengers speeding towards the low-level and Eastern sections, who meet another cross-flow coming in the opposite directions over the footbridges and through the narrow single barrier between the Central section and the low-level section.

During the 1930s there was an average of 446 people employed at the station. This included two assistant station masters, sixteen booking clerks, thirty-seven ticket collectors, seventy-two parcel porters, sixty-seven platform porters, seventy-four passenger guards, and a host of other workers. The station also ran a post office, which turned over £75,000 per year, much of its business coming from the sale of 107,000 postal orders, the sending of 52,000 telegrams, and the issuing of 196 dog licences and 854 radio licences – all services no longer required or available at post offices today.

Hop pickers leaving at midnight from London Bridge, 1891. ZPER34/99

London Bridge Station in World War II

During World War II some of the roads and archways under the station were used as air-raid shelters. One particular shelter was located along Stainer Street, running inside a London Bridge Station arch between Tooley Street and St Thomas Street. In October 1940 the shelter was examined by Home Office engineers and health inspectors, and the conditions they discovered were so shocking that one inspector stated that he found it difficult to put his impressions into words. The premises regularly held around 3,000 people sheltering each night, yet there was only one tap for drinking water, there was no flooring apart from trodden earth, and the few toilets that were present were entirely inadequate and located behind temporary screens with sacking material hanging as ‘doors’.

There were four exits from the shelter, one of which was large enough to allow trucks access, and next to this was a room where the hides of freshly killed horses were piled. Blood and the accompanying refuse was seen flowing out into the passage where the shelter bedding was stored. The medical officer reported that this was the finest breeding ground for an epidemic that he had ever seen.

There was a first-aid post, but it was manned by volunteers who had no medical training, and most of the medical supplies had gone missing anyway. Many of the passageways through the shelter were blocked by filthy bedding, and passengers using the railway during an air raid often preferred to take the risk of being above ground rather than staying down in the shelter. Even so, many people did use the shelter, and marshals were present to try to supervise the crowds – but anything they said was usually ignored. The police had refused to oversee the shelter since it was on railway property and they believed that railway staff should be running it. The Home Office report on the shelter ends with the inspector’s assurance that he had never seen anything more entirely sickening than these public shelters. He states that 120 more toilets should be installed, the rubbish should be cleared from the passageways, and three-tiered bunk beds supplied, along with at least one paid first-aider.

The Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Sir Philip Game, in a letter to the Home Office sent on 28 October 1940, made his thoughts clear on these shelters, calling them ‘death traps’. His concern was that the shelters were not strong enough to protect those inside. The crown of the arch was not proof against even a small fifty kilo bomb, and the long passageway needed to be divided up by ‘baffle walls’, which would contain any explosion damage to one small section of the tunnel. He urged the government to seek the advice of someone who had knowledge not only of the strength of materials, but also the blast and destructive effect of heavy bombs.

Sure enough, on the night of 17 February 1941, a 500 kilogram bomb hit the Strainer Street shelter, and another landed just outside in St Thomas’s Street. The second bomb was a delayed action device, falling at 10.30pm, but not exploding until the following morning. Out of the 300 people sheltering, sixty-eight were killed and 175 injured. Many of those killed were hit by the steel doors, each weighing ten tonnes and installed at the entrance to the shelter, and designed to protect those inside, which were blown down into the shelter when the bomb hit, crushing those underneath. Other casualties were medical staff from nearby Guys Hospital, who were tending to the injured when the second bomb exploded. The depth of the bomb crater and the amount of rubble were so great that it is thought that the bodies of some victims were never recovered, and still lie beneath the road that passes through the tunnel today.

Bomb damage at London Bridge Station, 1940–41. RAIL648/132

Modernization

After the war, electrification continued under British Railways from 1948, but by the 1960s, in common with other London termini, the dated layout, combined with sheer passenger numbers, meant that the station needed modernizing. Between 1972 and 1978 the station underwent major improvement works, receiving new signalling, a new concourse, and a new roof over the old SER platforms, although the original arched roof over the Brighton side was repaired and preserved. During the 1980s and 1990s the station remained largely unchanged, the main development being that platforms were extended to enable the use of twelve-carriage trains.

Below ground, however, the work on extending the Jubilee Line to East London provided the stimulus to redevelop the station’s link to the Underground system during the 1990s, converting the rundown area under the station platforms into a bright new booking hall, with shops and cafés added to the new complex, which opened in 1999.

‘The First Railway in London.’ ZSPC11-345

The Building of the Shard

Perhaps the biggest change to the appearance of London Bridge Station came between 2009 and 2012 with the building of a ninety-five-storey glass-clad skyscraper, stretching 309 metres into the air and towering above the station: the Shard, and Britain’s tallest building. It was built as part of the London Bridge Quarter redevelopment, which in effect provided a new roof over the terminal level concourse of the station.