20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

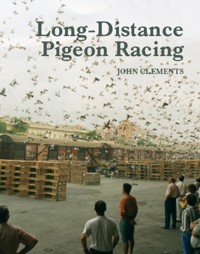

This authoritative book is aimed particularly at those who participate in racing pigeons at distances of over five hundred miles but will be of value to all pigeon fanciers. John Clements succeeds in making the reader view the humble pigeon in a different light and ensures that he, or she, gains a deeper appreciation of the enormous joy and satisfaction that can be gained from long-distance pigeon racing.Contains detailed accounts of interviews with the owners of nine top British and Continental lofts involved in long-distance pigeon racing. The interviews cover a wide range of important issues including the acquisition of stock, the treatment of young birds and yearlings, feed, health and immunity. Other subjects covered include loft management, cleaning, construction and ventilation, the pairing and exercising of the birds, the systems used (widowhood, on the nest, or both) race preparation and many other subjects. Well illustrated with over 170 colour photographs, pedigree charts and postcards. This easily accessible, informative and analytical book is essential reading for pigeon fanciers everywhere.The objective of the book is to make the reader look at the humble pigeon in a different light and gain satisfaction from the joy of long-distance racing. Provides fascinating accounts of interviews with the owners of nine successful lofts.John Clements is a dedicated commentator on long-distance pigeon racing; an enthusiastic supporter of international racing and has a regular weekly column in British Homing World.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 440

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Long-Distance Pigeon Racing

JOHN CLEMENTS

FOREWORD BY ALEX RANS, SECRETARY OF THE CUREGHEM CENTRE, BRUSSELS

Copyright

First published in 2007 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This impression 2013

This e-book first published in 2013

© John Clements 2007

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 669 7

Contents

Foreword

Alex Rans

(Secretary of the Cureghem Centre, Belgium, organizers of the International Barcelona)

I am pleased to be asked to write a foreword to this book because it confirms what I have been thinking and trying to do for many years. The book tries to get behind many modern techniques and take our thinking back to the pigeon itself. A return to the central role of the pigeon is long overdue. John Clements has done this by seeking out the views of successful fanciers who have, in their various ways, accepted the challenge of long-distance racing regardless of the circumstances in which they find themselves. Some have lasted longer than their contemporaries, some have achieved top results with limited financial resources, while others have succeeded in getting their pigeons to distances that not long ago were thought impossible. The one thing they have in common is that they have all accepted the challenge of breeding better pigeons to fly and compete in long-distance events.

Alex Rans seated at the desk from where he plans the Barcelona International.

If there is one message from this book it is that long-distance pigeon racing is essentially about the pigeon. It is from within the natural resources and unique ability of special pigeons that the sport will not only thrive but flourish. We must all begin to look from the pigeon outwards. The greatest improvement we can all make in our own lofts is for the pigeons under our care to breed a higher percentage of really good birds. Improved breeding will always improve everyone’s performance by the greatest amount. This book confirms this message by providing examples of those that have accepted the challenge.

Its central message leaves me more confident than ever that the sport has a brighter future than has seemed possible for many years. This will be achieved through improved breeding and the critical study of results. This book will become a part of all our futures and perhaps even the future of the sport itself.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank all the fanciers I have interviewed for this book, not only for their valuable and honest contributions, but also for the excellent meat and drink I have enjoyed during my visits. I would particularly like to thank two fanciers and their wives, Russell Bradford and his wife Clare, and Geoff Cooper and his wife Catherine, who not only fed me but showed extra hospitality by allowing me to sleep overnight, followed by a hearty breakfast the next morning. I really wish to thank Alan Darragh and his wife for picking me up at Belfast airport and delivering me back after my work was done – this was more than helpful. The many times I have visited Herman Brinkman, Jelle Outhuyse, Ad Hagens and Bernard Deweerdt have always given great pleasure. You can easily see why they are all such good fanciers – choosing a wife in the first instance must be a part of it. I cannot forget to mention Nigel Lane and his wife Judith. It was Nigel who took me to France to interview Robert Ben in Calais. Unfortunately I was delayed by road works on my way to meet Nigel. Not only did he turn around when half way to the Channel Tunnel, but not once did he complain about having done so. I thank him enormously.

Lastly, may I thank Alex Rans, the Secretary of the Cureghem Centre, for writing the foreword. Alex has always been more than helpful in so many ways. I appreciate it more than I can say.

John Clements

Stockport, 2006

Photography Acknowledgements

The author and the publisher would like to thank the following individuals and organizations for providing photographs and for granting permission for them to be reproduced in this book:

The Bath Chronicle

Peter Bennett, Darlington

Anthony Bolton, Broadstairs

Sid Collins, Doagh, Co. Antrim

Catherine Cooper, Peasedown St John, Bath

Henk Kuijlaars, Gravenzandweg 20, 2671 JR Naaldwijk, The Netherlands

Martin Kwarkernaat, De Vredenburg 20, 3291 GC Strijen, The Netherlands

Keith Mott, Esher, Surrey

Northern Ireland Provincial Amalgamation (F. C. Russell, Secretary)

Peter van Raamsdonk, Kerklaan 45, 2291 CD Wateringen, The Netherlands

Bryan Siggers, Pigeon Photographer, Ash Vale, Surrey GU12 5LE

Jelle Outhuyse, Harlingen, The Netherlands

Foto Sinaeve, Stationsstraat 23, 8110 Kortemark, Belgium

Els de Weyn, Steenakker 212, 9000 Ghent, Belgium

Jan Van Wonterghem, Kortinghse Straat 14, 8520 Kuurne, Belgium

CHAPTER 1

Herman Brinkman

Tuk, Steenwijk, The Netherlands

BACKGROUND

Herman Brinkman lives in Tuk, a small suburb of Steenwijk in the province of Overijssel. Quiet and unassuming, he is a languages teacher by profession, his speciality being German; his English is also excellent. He is fully committed to pigeon racing at extreme distances. It is his life’s work. You know he believes in what he is doing from the way he smiles and his eyes twinkle when the subject is mentioned. Anxious for his advice, you are obliged to wait, for this quiet, capable man is inclined to let you talk first while he listens. He then says much less than you would like, but that is his nature.

John Clements and Herman Brinkman.

The distance from Barcelona to the Brinkman loft is 1,306km (816 miles)

He has of course won many other awards, including championships. From 1994 to 1997 he was champion of the National ‘Fondspiegel’ competition in different categories. Seventy-six times he has had pigeons in the top thirty in national races. Many other fanciers have done well with his pigeons. Even Alex Rans, the Secretary of the Cureghem Centre and the organizer of the International Barcelona, has Brinkman birds and has done well with them. Jan and Hanne Sas from Vorselaar (Belgium), Bennie Homma from Balk (Netherlands) and Beullens and son of Heverlee (Belgium) won 9th, 27th, 74th and 111th National Barcelona. As recently as 2004 a pigeon of W. Derksen of Almelo in the Netherlands, with half ‘Brinkie Boy’ blood and flying over 1,200km (750 miles), was 72nd International Barcelona, beating Herman himself (78th) in the same race.

The Netherlands showing the Northerly location in the Netherlands of the Outhuyse and Brinkman lofts, both flying more than 800 miles from Barcelona.

Map of the five original Race Points (four in France and one in Spain) used for international events organized by Belgian Clubs. The countries that usually take part in these races are Germany, Luxembourg, France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Great Britain, but Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia also enter from time to time. Barcelona is the longest race and generally considered the premier race of the series. Barcelona re-started in 1951 after World War II with an entry of only 2,039 pigeons. It has grown over the years to well over 25,000 pigeons.

The Brinkman loft in winter.

THE INTERVIEW

THE START

How old are you, when did you first start with pigeons and when did you move up to long-distance pigeons?

I am now fifty-six years old. I started with pigeons while I was still at school, probably about twelve or fourteen years of age. My father had the pigeons. I was only allowed to clean them – I was not given the luxury of making decisions.

I was eighteen years old when I first came into contact with a long-distance pigeon. I was at University at Groningen at the time. A neighbour gave me a very good hen that was first in the National from Ruffec in an overnight flight. Later on, in October I think it was, I came home from Groningen and went in the loft. The hen was missing. I asked my father where the pigeon was and he told me, ‘This pigeon was not a good pigeon for it only won one prize, so I put it out.’ My father was not a long-distance man; his requirement was for pigeons to fly every week and win many prizes each season. This is an example of the difference between long-distance thinking and middle-distance thinking.

What stock did you first buy for the long distance and do you still have some of these pigeons in your present colony?

Later on I persuaded my father to have some long-distance pigeons. My father and I went to Ko Nipius for some Jan Aarden pigeons. He was a top long-distance man at that time.

That was the start with long-distance pigeons. Almost nothing is left of those pigeons now, but one of my early great pigeons, ‘Fijne Zwarte’, has contributed greatly to my colony and some of this blood is still present in the family today.

By the time I was twenty-seven and thinking of getting married and setting up on my own, I was firmly convinced that long-distance racing was what I wanted to do. You could say I was sold on the idea. Because I would need furniture for my new house, I decided to combine the two ambitions. I went to buy furniture from Hans Eijerkamp, who was and still is one of the biggest furniture dealers in Holland. Hans is also a pigeon fancier.

In those days if you bought furniture from Hans Eijerkamp, as part of the deal you got some pigeons for free. I asked him for some of the best long-distance pigeons he had. He promised me four from the best of the Van der Wegen strain. These pigeons were of impeccable pedigree, the best he had. They came from such illustrious ancestry as ‘De Lamme’, ‘De Barcelona’ and ‘Oud Doffertje’, all foundation pigeons of the Van der Wegen family. Of course I was anxious to see what such pigeons off such a good strain would look like. When they arrived at my house in Tuk, I was so disappointed with them I thought of sending them back. They looked so small and insignificant, not at all what I expected.

I telephoned Hans and he told me that of course he would change them, but if I were wise I should hang on to them and wait to see how they developed. Reluctantly I agreed and I’m glad I did. These four original Van der Wegen pigeons are now famous: three of the birds turned out to be champion breeders. I learnt a valuable lesson from this. Long-distance pigeons do not always look the part. Indeed, long-distance pigeons are not always beautiful. What is absolutely necessary in long-distance pigeons is for them to be of good racing ancestry. Good looks are secondary. Even today, and in spite of the experience I had with the original Van der Wegen birds, I am still inclined to select young pigeons by looking and handling, but I have learned to curb this tendency a bit. Every year I write down the ring numbers of what I consider to be future good prospects, but these selections almost always turn out to be wrong when subsequently tested in actual races. My son makes fun of me for being so wrong. Where I am possibly a little bit clever is that I admit I do not know how to select pigeons accurately before they have flown, even though I still do it. Over the years I have learnt to leave a lot to the pigeons to prove themselves. It is they who have to do it, they who have to fly the races and decide how to get home. I should have more confidence in the pigeons and less in my ability to select. The only thing I can do is to try to breed ability into the flock as a whole and hope super ability comes out from time to time in individual pigeons.

THE FIRST CROSS

When did this happen?

In 1990 I bought pigeons from Vertelman and son of Hoogkarspel. I thought my present colony was getting too inbred. These Vertelman pigeons were based on the strains of Jan Theelen, Martha Van Geel and Van der Wegen. I think I bought twelve pigeons from Vertelman. One of these was a pigeon that turned out to be one I later called the ‘Golden Breeder’. He produced good pigeons from the very start. Among the first pigeons he produced were ‘Brinkie Boy’ and the ‘Drie Barcelona’, both very good pigeons. ‘Brinkie Boy’ won first National Limoges. The ‘Golden Breeder’ was mated with ‘633’, which as a yearling was 20th National Bergerac. This pigeon had the old original Ko Nipius blood in it from ‘Fijn Zwarte’ and some of the Van der Wegen blood going back to ‘De Lamme’.

Brinkie Boy, a first cross that went on to produce winners. Brinkie Boy is a favourite of Herman Brinkman. Photo: © Copyright Peter van Raamsdonk

A current ‘Champion’: ‘Barca Boy’ – 78th International Barcelona 2004.

Again, as so often happens in long-distance pigeon racing, not everything was a success. At the time I bought the Vertelman pigeons there were also two full brothers of the ‘Golden Breeder’ in the same kit of pigeons. These two brothers produced nothing worth mentioning. This is an example of something you find time and time again in long-distance pigeons. Only a few individuals have that vital ingredient to be champions. Even fewer can pass this vital ingredient on to their offspring.

What influences you when you import stock into your loft? Must they be bred from sons and daughters of good birds, and do you have a preference for either cocks or hens?

First of all I study results from the National and International races. I also take note of the distance flown and the numbers taking part in these races. In 1990 I spotted the name Vertelman and sons of Hoogkarspel, here in the Netherlands. They were doing really well and were on top form at the time. Their results were fantastic. I noted that Vertelman was 9th National from Barcelona, a distance of 1,277km (800 miles). I thought 9th National at this distance was so good I must visit him and see the man and the pigeons for myself. I didn’t know him personally, so I telephoned and arranged to visit him.

Territory – each cock owns its nest box.

Pedigree of Brinkie Boy.

I always think anything you use for a cross must be off good top-quality birds that are performing well at a similar distance to your own and are raced in similar circumstances. Both cocks and hens are important, but I think as a general rule the good cocks come from good hens and good hens from good cocks. Occasionally a super breeder will produce both good cocks and good hens, but it is very rare. In fact good breeders are very rare themselves. You must always be on the look out for good breeders in your own loft; they are the future.

I will give an example. This year I bought a pigeon from the 1st National Brive. I will probably breed twenty pigeons from him. If the pigeons as a team are not up to standard and fail to live up to the criteria I need, then the whole lot must be disposed of. I must make up my mind quite quickly. I do not allow more than two or three years at the maximum. I can’t afford to wait about with new pigeons, considering the space I have and the number of birds I can keep. They have to be better or at least as good as my own.

Have you made any mistakes?

Oh, yes. I can’t name names, of course, but I have bought pigeons with exactly the right pedigree and performance and still they have failed. The whole business of breeding pigeons for long distances is fraught with difficulty. Some that I have bought with great expectations did not do any good at all. It is a gamble, I think. There is one thing, though. When you visit someone with the intention of buying birds from him, you must feel the man wants to help you. If you feel this then it is likely you will get pigeons off some of his best birds, and then you have a chance. If they are not off the best, and are not backed by good performance, then you have little chance. Here in the Netherlands we are lucky that we are able to compete in top races of undisputed quality. My position here in Tuk is not ideal, however, because I am one of the longer flying fanciers. I am mostly at a disadvantage in international races because of the distance, but it would be a huge mistake to avoid competing at the top level because of this reason. You must always compete against the best, regardless of your position, if only to test your breeding against the best birds and in the best races available.

THE RACE TEAMFROM YEARTO YEAR

How do you treat young birds in the year of their birth? Do you race young birds? What do you expect of them? Do you breed late breds?

I race them but I don’t expect anything from them. If I can, I try to race them to 400km (250 miles), but I go on holiday in late summer so it is not always possible. The pigeons always fit in with my life style and family commitments. I do rear a few late-bred youngsters off the best birds after they have finished racing for the year.

How are the late breds treated and are they, as is generally perceived, a lot of trouble?

When I visit my father, who lives some kilometres away in Raalte, I take them with me and release them there. I do this all through the winter months regardless of the conditions. This year I bred twelve; I lost two of them, not in training but taken by hawks.

No, I do not think they are a lot of trouble providing you are patient. Late pigeons, because they are born in the summer in good weather, have the best conditions to grow. Late pigeons are generally bred from better parents. For all these reasons I think they can be better birds than others, but you must be patient and wait for them. Generally they are healthier. Some of my best pigeons have been hatched late in the year. I think they are worth waiting for.

How do you treat yearlings? How do you evaluate them and what do you expect of them?

If it can be arranged they fly in a race from 800km (500 miles), though that is not always possible. They are not expected to win a prize: all they are expected to do is to get home in reasonable time. They are introduced to widowhood and raced on widowhood as yearlings.

Do you evaluate them in the hand?

I do, I can’t resist it, but most times I am wrong. The basket is a much better selector. I make many mistakes. I don’t think there is one fancier in the whole world who knows which pigeons are better before they are tested by the basket. I don’t think it is possible to know this sort of thing. You can look at muscles, eyes, bones and all these things, but the basket is still by far the best guide simply because we can’t see inside their heads.

Is there any physical attribute you particularly look for in a mature pigeon? Are you looking at the wing, the throat, the head, a particular shape of the body or what?

I do like good feather, but for the rest, the basket is best. Good pigeons come in all shapes and sizes.

IMMUNITY

Do you consider a high degree of immunity to illness essential for a long-distance loft to perform well?

Dirty lofts that have not been cleaned out clinically are good since they cultivate high immunity. Over time such lofts build up a sound constitution that helps race birds contend with confinement in the basket during races. Often the healthy pigeon you have sent to the race sits next to a sick pigeon for four or five days in the race pannier. In conditions like this they should not easily fall to ailments of any kind; indeed, while some pigeons that lack a good immunity are losing form, yours should thrive and possibly gain form. There is something else to consider. During preparations for a really long race it is essential that things go well in the races leading up to the big one. Any kind of sickness interrupts smooth preparation. A good immunity helps to achieve protection in the build-up phase so that form increases, rather than decreases, on the run up to the important race.

Do you also think that quite dirty lofts, like yours, help the pigeons to be more content?

Yes, I think it is important that the pigeons feel at home in the loft. If you are interfering all the time by constantly scraping and cleaning, contentment suffers. You have to realize the loft is their home; you have to recognize and respect this. To further help contentment I have an aviary in front of each loft where the pigeons can go out all through the winter. The aviary has a wire bottom through which the droppings can fall. Most of the time they prefer to sit outside. This is also good. It is good to allow the pigeons to have a choice but in some things you cannot allow choice. The pigeons have to be vaccinated every year for instance. This you must do. My pigeons are vaccinated for paramyxo and pigeon pox in one combined dose.

If illness, such as a respiratory condition, were to arise spontaneously, would you immediately suppress the individual or its offspring without attempting to treat the pigeon, or would you allow it to persist and wait for the pigeons to get over it?

If the loft is well built and has good ventilation then you have no problem, but if something persists you have to do something about it and treat each pigeon individually. In my experience, if the loft is well designed with good ventilation then you usually don’t have a problem.

But three weeks before Barcelona I do treat with Linco Spectrin, which is a mild antibiotic for the breathing, and for trichomoniasis (canker).

Do you think that these treatments affect the form of the pigeons?

Yes, I think they can. It’s not always good and form can suffer, but if everything is given three weeks before Barcelona they have time to build up form in time for the race.

Do you use anything like garlic or extra amino acids on their food, something for form like oil, or even peanuts?

No, I have tried all these things and they do not help, especially in long races. The only extras I use are some small seeds I give them prior to the long races. But perhaps I am old-fashioned. I know supplements help racing cyclists. Perhaps I should take another look and see if I can improve things a bit, but at the moment I don’t have any plans.

ADVICEFOR THE NOVICE

What advice would you give a novice attempting to build a team of long-distance pigeons, and what stage should he have reached after three years?

A novice should start with ordinary healthy pigeons and use them as feeders. He must then go to two very good fanciers who have good results at the distance you require and buy eggs off their best birds. The two fanciers must have different strains of birds.

After three years he should be racing very well – not international races, at extreme distances, but National and overnight races.

To be truthful I really don’t think you have allowed enough time for him to evaluate himself. The first thing is, he must have a very good loft. A dry, well-ventilated loft is essential, and such a loft, with good ventilation and conditions, and where the birds are happy, can only be achieved by trial and error. If he is to be a good fancier he must be motivated and patient at the same time.

BEFOREAND AFTERTHE RACE

Do you fly widowhood, on the nest, both systems or something else?

Most of the time on widowhood, but this year I had twelve couples on nest. The nest hens were coupled with twelve stock pigeons so the cocks were always there when they returned from races.

Are the yearlings on widowhood and how much exercise do they take?

Yes, I have a total of fifty cocks on widowhood, including the yearlings. I encourage them to exercise freely around the loft. It is very, very important, perhaps the most important thing of all. They must exercise around the loft twice a day for 90 minutes each time. I have a ball that I throw at them to start them off. They perhaps begin with as little as 20 minutes, but gradually I build them up to 90 minutes twice a day. Exercise around the loft is very important – if they don’t exercise then you can’t hope to get a prize.

Can you give me some idea of how you would treat a three- or four-year-old widowhood pigeon being prepared for big races such as Barcelona or Perpignan?

This year I didn’t breed from the older pigeons, those that are three or four years old or more. It is important to forego breeding in order to delay the wing moult. When they are racing from Perpignan in August I want a good wing. I want two or three moulted flights only. If you do not breed in the early part of the year this is then possible. If you breed and rear youngsters early the breeding kick starts the moult sooner than you would like. The yearlings that are only going to 700 or 800km (430 or 500 miles) are bred from, but the older pigeons are not.

Do the Perpignan pigeons also go to Barcelona or, should I say, do the Barcelona pigeons go on to Perpignan in the same year?

That is the intention, but it’s not always possible if it is a hard race from Barcelona. It’s too much to ask of the pigeon in such conditions at this distance. If it is an easy race from Barcelona then it is possible, but not every year is easy. If you push them beyond their limit you can lose too many good pigeons. They may look all right on the outside but inside they are not so good. You can’t ask a pigeon to give everything twice in one season. A pigeon must always have reserves it can call on.

This year, before Barcelona, I raced the pigeons from Ruffec, a distance of 866km (540 miles). After this race they rested for three or four weeks prior to Barcelona. They need to conserve energy and stamina for such a race, but every week I give them the hen to keep their interest and train them for 50km by car. The hen is always waiting. Apart from that I do nothing.

Regarding the hens that are raced to the nest, what condition are they sent in and how are they trained?

The best condition is for the hen to be sent sitting on a three- or four-day-old youngster. Some hens are good on eggs, but most of the time sitting on a such a youngster is the best. I do not train them by car or anything like; they must exercise at the loft in the early afternoon while the cocks are sitting on the eggs. I don’t know if that is good enough, but my circumstances dictate that I do it this way. If I were at home, instead of working, it would be possible to exercise the hens twice a day, but when you have a job that’s not possible. With pigeons there is always a compromise to be made. I think with more time I could do better with hens.

What do you do in the final three or four days before basketing for an important international race and what do you do after they come home?

I give them some small seeds with their food – nothing special. I don’t give peanuts or anything like that; maybe it is good, but at the moment I don’t do it. After the race they are allowed to rest. I don’t allow the hen on the first day they return, so I lock them up alone and feed them in their box, since the box that’s their territory is their reward for the effort they have put in. Cocks are prepared to suffer a long flight just to return to their box. They have the hen on the second day, then after a day or two they are allowed to go outside. I don’t want them to have to fight for their box immediately they return owing to the condition they’re in. A tired pigeon forced to fight when it is not in top condition would have its morale destroyed for a whole season, and possibly for the whole of its career.

I’ll give you a good example of how territory works and how you can take advantage of this trait in a pigeon’s character. In 2001 I won the 5th National and 14th International from Barcelona. That year a yearling was lost, so the pigeon that was to fly Barcelona ended up occupying two boxes, his own and that of the lost yearling. When he came back from Barcelona everything was closed – it was so early in the morning I didn’t expect to see anything so soon, certainly not from Barcelona. I opened the section where he normally was, but he didn’t want that and went over to the yearling’s box on the other side. That year he raced and was competitive for extra territory, the yearling box as well as his own. This pigeon cultivated his own motivation. As events turned out it worked very well and he flew a magnificent race.

Hermanator – 14th International Barcelona 2001 against 25,760 pigeons. Photo: © Copyright Peter van Raamsdonk

Brinkie Girl, a daughter of Brinkie Boy. Photo: © Copyright Martin Kwakernaat

Motivation originated by the pigeon itself is very important – I think motivation turns an ordinary pigeon into a special pigeon on the day. But he must want to do it himself. Motivation is best when the pigeon learns at its own speed, not when its learning is imposed by a time-scale to suit its owner. The pigeon in question, the one that motivated himself, I called Hermanator. He is now a top breeding pigeon of the loft.

Red Barcelona, the grandfather of ‘Hermanator’ and himself a top-class Brinkman pigeon. Photo: © Copyright Peter van Raamsdonk

Pedigree of Herminator, a pigeon that goes back to ‘046’, the ‘Golden Breeder’.

THE MOULTAND WINTER TREATMENT

Are the pigeons separated for the winter and, if so, when? Do they get any special treatment?

After racing they are allowed to rear a youngster. They are then separated. They are given plenty of baths at this time and good moulting food, but nothing extra special. Separation improves the moult and in my opinion improves the quality of the feather. Silky feathers that come from a good moult indicate health.

PAIRING UP THE BIRDS

When do you pair the race birds and the stock birds?

I pair the race birds about 25 March and the stock birds in December. For the stock birds I keep the lights on in the loft a little after dark in an attempt to simulate longer daylight.

What physical characteristics do you look for when pairing up the birds? Do you compensate for size or colour of the eye, etc?

Every year we go to Texel, one of the West Frisian islands off the northern coast, for an autumn break. Cars are not allowed on the island, so in the long quiet evenings I make a ‘couple list’ and pair the birds on paper. When I get back to the loft this sometimes changes, but the last few years I have followed a rule that if a pigeon has a light eye I always couple it with one with a dark eye. I don’t know if this really matters but I do it. The feather colour does not matter – if they are good at racing then anything goes.

THE LOFT

What do you consider important for the construction and ventilation of the racing loft?

Ventilation is very important. If the cocks live for a whole year in a loft without good ventilation, you win nothing. After a loft has first been built you need to make adjustments in order to refine the ventilation so that it is as near perfect as possible. Buildings and other nearby features can have an effect on the ventilation, as can trees and the direction the loft is orientated. The loft must also be absolutely dry: you can smell a loft without good ventilation. Of course, you must not overcrowd the pigeons.

NUMBERS

How many birds do you have in your race team?

I have fifty widowhood pigeons, including yearlings. There are also twelve pairs of breeders and I breed approximately eighty young birds each year.

At the end of the year do you expect to have eighty left?

No, definitely not. Most years about fifty or so are left. This means I have twenty-five yearling cocks for widowhood the following year.

Would you like to have more pigeons?

Even if I were a very wealthy man with unlimited resources I would not want to have any more. I have too many already. The clever fancier is the man who has few pigeons. If you have too many, breeding and racing can get out of control – you can become less efficient, you notice less and the pigeons do not perform as well.

Do you consider a certain number of breeding pigeons an essential minimum for maintaining the quality of your colony?

Yes, I think twelve breeding pairs are absolutely necessary, including a number of experimental pairings.

As regards racing, in order to compete in overnight races and the international programme you need at least fifty pigeons, but quality must always come first. If necessary you should enter fewer races with top-quality pigeons rather than more races with average pigeons, but always enter races where the standard is high as soon as you are able. If you do well in events of a high standard you will have a good idea of the quality of your family of pigeons and how your breeding is coming along.

THE MAIN BIRDS

Which individual stock birds were essential to the development of your colony?

The ‘Fijn Zwarte’, the ‘Golden Breeder’, the original Van der Wegen pigeons from Eijerkamp – all were good pigeons. All have left their mark.

Can you tell us about the most important race birds you have had and the ones that established your reputation? Which is your favourite?

I have had many: ‘Hermanator’, ‘Brinkie Boy’, ‘Tukse Lady’, ‘Brinkie Girl’, ‘Red Barcelona’ … there are many. I think ‘Brinkie Boy’ was my favourite. He was also an excellent breeder.

Did these individuals display any particular traits?

No, they were all normal pigeons.

Have you any idea what made them so great?

In truth I think it was good blood, but many pigeons with good blood do not breed or race well. Good blood is only the start. I really think it is something inside them we can’t see. It is this invisible element that makes long-distance pigeon racing so fascinating. The only thing we know is that whatever is present in pigeons with good blood is also likely to be there in pigeons that have proved themselves at flying long distances. It is certainly there in pigeons that have proved their ability to produce top long-distance pigeons when coupled with different mates. There are not many who can do that.

Teletext record of the Herminator performance from Barcelona in 2001, when he was 14th International and beat many pigeons flying a lesser distance.

A LIFE IN PIGEONS

How do the pigeons fit in with your family life?

My wife Ria is interested but doesn’t actively do anything. My sons are also very interested, but at the moment Jan is at University so he doesn’t do much. Pigeons are important to me and I can’t imagine life without them, but they are not everything. Three or four times a year my family go away on holiday together – they are most important.

REDUCING THE ODDS

Racing pigeons at long distances is always a challenge and full of uncertainties. By its very nature we can never know everything. You have been more successful than most fanciers in the sport, so can you single out the one technique or quality that has helped reduce the uncertainty, shorten the odds and, to some degree, helped produce a successful colony?

The fancier’s motivation is very important: if you don’t have motivation the loft will be no good. Motivation also goes in cycles. You must keep learning new things. The act of learning motivates. Making discoveries keeps a fancier interested. If you think you know everything you are already on the way down. If motivation isn’t there you cannot even identify good pigeons to keep your loft at the top. Among other things motivation makes one more aware.

Do you have any further ideas and ambitions?

Ten years ago my loft was stronger than it is now, but since my sons were about to go to University I sold half of my pigeons to help with the costs. I am now building up my strength again. I am always trying out new ideas, innovations and methods. All lofts go through their ups and downs. It’s just like a football club – you can’t have a full squad of the best players all the time. When it does happen your loft is at its maximum strength and you are at the top of competition. Staying at the top is difficult.

LONG-DISTANCE RACING AND ITS SPIRITUAL QUALITY

The fact that you are disposed to race long-distance pigeons suggests to me that this type of racing has a spiritual quality about it. Are you intrigued by the pigeons’ ability to fly extreme distances?

I’ve always been interested in the development of the pigeon itself. In sprint and middle-distance racing the fancier is important, but in long-distance racing the pigeon is the key. It’s the pigeon that must fly the distance – the pigeon that must make the effort and win the achievement. There is indeed a spiritual quality about racing, but to be honest it gives me great pleasure. When a pigeon makes it back from Barcelona it is very nice. The pigeons make it very pleasing. It is rewarding for the spirit to be the one who has trained and raced a small bird that can fly such a long distance. There is very little in life that gives more satisfaction than this.

CONCLUSION

THE BRINKMAN CONTRIBUTION TO PIGEON HISTORY

In summing up Herman Brinkman’s attitude toward and experience of pigeon breeding and racing, one becomes aware of what he has decided to leave out rather than what he does. His pigeon operation is uncomplicated. It is basically a simple, no-frills affair: nothing is done at the Brinkman lofts that is not thought necessary for the improvement of the pigeons. The breeding policy is intended to provide sufficient good pigeons, year after year, ready and able to fly the extreme distance. This is easier said than done. In his day-to-day management Herman would rather not do something than do it without reason. He would rather recognize and accept failure than ignore the consequences. The Brinkman philosophy accepts that, when it comes to breeding and racing long-distance pigeons, not everything is even half understood.

AN INEXACT SCIENCE

Breeding, of course, is the basis of most long-distance pigeon racing. To this end there is a constant search for quality pigeons. Herman Brinkman knows better than anyone else that breeding is far from an exact science. He admits his mistakes, but despite failures he is always on the look out for pigeons able to improve the present colony or help produce birds capable of flying the Brinkman distances. In order to stay a part of the loft the youngsters off the imports are expected to pass performance criteria similar to those Herman expects of his own pigeons. This is a tall order, but that is why Herman Brinkman’s contribution to the history of pigeon sport has been that of a giant, shrinking the 1,300km (800 miles) distance from Barcelona down to something that can be flown with a measure of consistency. In his way Herman Brinkman has inspired fanciers across Europe. Since 1986, when he first sent a lone pigeon to Barcelona and was 2,163rd from a field of 18,076 birds, he has improved gradually to being 14th International in 2001 from 25,760 pigeons. Breeding excellence is part of his contribution. His birds are valued for their extra strength and tenacity, largely because of the distances they fly.

EXTRA-HIGH QUALITY

Only high-quality pigeons are imported. These pigeons are carefully selected and their credentials examined before they are chosen. The choice is based on successful results at a distance similar to that which the Brinkman lofts fly (the Vertelman pigeons are an example), but even with these precautions it is not always possible for every import to be successful. Herman has admitted that, in spite of all his precautions, mistakes can still be made, since breeding can never be exact. Breeding for performance is more of a statistical exercise for the simple reason that there is not enough information from which to make a full assessment. Herman cites the fact that two brothers of the ‘Golden Breeder’ (the father of ‘Brinkie Boy’) were imported at the same time, but one produced nothing of quality while its sibling, bred in exactly the same way, became a cornerstone of the loft.

Pedigree of the latest Champions. ‘Barca Boy’ – 78th International Barcelona 2004.

THE LOFTS

After the breeding has been done, the next problem to be solved is the housing of the pigeons, the way they live their lives. There is no point in breeding pigeons of potential quality if the loft does not provide the necessary contentment, security, health and happiness. All these are necessary for the pigeons to perform at their best.

VENTILATION

Herman Brinkman knows a thing or two about ventilating pigeon lofts. He aims for a flow of continually renewed air without ugly draughts, believing that if the ventilation is right, then the respiratory system of the pigeon itself is also likely to be all right. Ventilation produces good health as well as a pleasant atmosphere. Herman stresses that you can’t buy ready-made good ventilation. Every loft is different, due to its location and its construction: a loft that is good in one place may be a failure elsewhere, even though its structure is the same. Continual adjustments have to be made in order to get ventilation exactly right.

AN AVIARY

The racing lofts also have an aviary in front of each section to further enhance the ventilation and the health of the pigeons. Dry lofts with perfect ventilation are of the utmost importance to Herman Brinkman, but aviaries also serve a necessary function by enabling the birds to take baths without dampness of any kind affecting the main loft. An aviary also allows them a view of the sky.

DAMPNESS

This heading should perhaps more appropriately appear as ‘dryness’, for it is the dry atmosphere and floor conditions that allow the Brinkman lofts to accumulate droppings and exist without constant cleaning out. This practice not only allows for easier management but is also an example of how Herman Brinkman thinks ‘pigeon’. The pigeons are undoubtedly happy to be left as nature would intend them to live. They love the apparently haphazard management (or apparent lack of management), but most of all they love being left alone. The pigeons are happy and comfortable with this style.

THE BOND

It is not considered essential for Brinkman pigeons to be managed in a tidy way. Instead the pigeons are encouraged to make up their own minds on the way they wish to live and go about their lives. This promotes a developing bond between them and the place they live that grows stronger with age. That is one of the reasons why Barcelona pigeons are kept until they are four years of age, by which time the pigeon is at full strength, before they are put to the most difficult task.

It goes without saying that a strong bond to their home is essential if we wish to have pigeons exert themselves over 800 miles. A bond to the loft is in itself a kind of motivation. When this bond is further heightened by individual territorial motivation, as it was in the case of ‘Hermanator’, an exceptional performance may be in the offing, provided the pigeon has the breeding quality and preparation necessary for the job. As Herman always reminds us, however, it is the pigeon that has to do it; we should never forget that.

UPS AND DOWNS

Herman Brinkman has the habit of comparing the sport of pigeon racing with that of other sports. Given his passion for football, he compares the ups and downs of a football team to the ups and downs of a colony of pigeons. This cycle of quality, in pigeons as in football, almost always rests on the star quality of the team as a whole. The ability to produce star pigeons almost completely depends on breeding. Without high-quality stock good pigeons are not produced and the loft inevitably declines.

MOTIVATION

Brinkman also draws our attention to another cycle, the motivation of the fancier himself, which similarly goes in cycles and has its ups and downs. If a fancier is motivated he is more likely to notice the potential star pigeons within his team and take action early in their lives. If on the other hand he is not motivated, or his motivation is low or non-existent, then things tend to get overlooked. In such circumstances good pigeons with a lot of potential may not only fail to be noticed but are often treated wrongly. When a fancier’s motivation is high everything is noticed, including the fancier’s own mistakes. That is a Brinkman lesson for all of us.

CHAPTER 2

Jelle Outhuyse

Harlingen, The Netherlands

BACKGROUND

Jelle Outhuyse (pronounced ‘Yeller Out-Houser’) is relatively young to have earned success in the world of long-distance pigeon racing. Usually, those who are successful at this level are mature, well-seasoned men or women who either have a lifetime’s experience behind them, or are following in the path of a parent or a close family member. Jelle is neither of these. He is only thirty-nine, has two young daughters and works full-time in a shipyard in Harlingen, his hometown. Yet despite these commitments, a modest loft and not much time, he has already made a mark in international racing. It is for this reason he is interesting. Can he last? Will he improve? Is his success dependent on a particular good breeder that he happens to own at this time?

Jelle Outhuyse – One of the longest-flying fanciers in the Netherlands – His distance from Barcelona is 835 miles. He is only 39 years of age and works full-time in a shipyard. Photo: © Copyright Jelle Outhuyse

These questions have yet to be answered, but I think he can last, since this Harlingen man is more than a passing comet that briefly lights up the sky. Jelle Outhuyse is here to stay for the simple reason that his character is that of a long-distance man through and through. He is determined, his only interest is in long-distance pigeons and his stoic temperament is suited to the task. In my opinion he will become a long-distance giant whose pigeons will influence generations to come.

Harlingen, an ancient port in the province of Friesland, is almost as far north as one can go in the Netherlands. Jelle Outhuyse is the longest flyer in this book. Despite this disadvantage – his distance from Barcelona is 1,335km (834 miles) – his pigeons have already flown outstandingly well from Pau, Barcelona, Perpignan and Marseilles. Jelle is a thinking man with the potential to achieve an even brighter future in the sport. He is much too reserved to postulate on such things, but you can bet he is thinking about it. He is a very determined individual.

Town Hall Harlingen – The majesty of its civic building shows Harlingen and its important past.

A view of Harlingen. This attractive Friesland town of canals and ships has always earned its livelihood from the sea.

THE INTERVIEW

THE START

How old are you and when did you first start with long-distance pigeons?

I am now thirty-nine years of age and I started racing long distances in 1990. No one in my family was ever interested in pigeons of any kind. I was the first.

What stock did you first buy for the long distance and do you still have some of these pigeons in your present colony?

Although I started with programme birds in 1990, my present family of pigeons is still based on Van der Wegen pigeons I bought from Nico de Heus of Hedel in 1992. The main producer of my family is a cock from 1993 that is still breeding. Although he still filled his eggs in 2005 and looks in very good condition, he may be coming to his end. I’m keeping my fingers crossed that he goes on for a few more years. His contribution to the loft cannot be overestimated.

THE CROSS AND ITS EFFECTS

Have you since brought in fresh imports to cross with your present colony?

Yes, every year I have bought one or two pigeons, including some from the Martha van Geel strain and more of the Van der Wegen pigeons. You must always be on the look out for good pigeons to cross with your own. I look for pigeons bred from birds with results at the long distance. I don’t especially concentrate on lofts similar to my own or on pigeons of a similar shape to mine, only on results. It is the genes you buy, not looks. The only thing I do insist on, however, is that the pigeons must not be too big: medium to small birds are better for long distances.

‘970’, the most important stock bird of the Outhuyse loft. This pigeon has already bred the 1st and 3rd St Vincent as well as 13th National Marseilles. His blood is in almost all the pigeons in the Outhuyse loft. Photo: © Copyright Jelle Outhuyse