13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

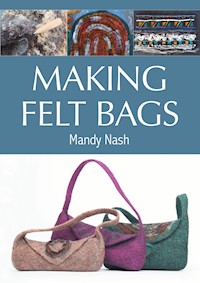

Feltmaking is a popular and exciting contemporary medium, expanding in many new directions. This practical book focuses on the specific requirements for making felt bags. It explains the principles of using a resist to create 3D forms, and looks at shapes and styles of bags to suit all occasions. Clear instructions on feltmaking techniques for beginners are given. A guide to equipment and to choosing appropriate wool breeds and decoration for individual projects are given too. There is advice on design, choosing handles and fastenings, and the functionality and the form of a bag. There are detailed practical, step-by-step instructions for nine projects, covering both basic and advanced options, with easily adaptable elements. It is a fabulous guide to the various processes necessary to create a functional and unique felt bag.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 126

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

MAKINGFELT BAGS

MAKINGFELT BAGS

Mandy Nash

First published in 2021 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

This e-book first published in 2021

© Mandy Nash 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 863 4

AcknowledgementsI have my grandmothers, Alice and Muriel, to thank for starting me off on my creative journey, passing on their traditional textile skills with boundless patience. My parents have to take some credit too, with their non-judgmental attitude towards my career choice and constant support and encouragement.

A special thank you must go to Heather Potten. An exceptional proof reader, she ensured that the content was understandable. Thanks too, to Eva Leslie, Jenny Rolfe and Jackie Stringer for double checking the text.

I must credit Heidi McEvoy-Swift for inventing the shrinkage test sample in Chapter 3, which is such an invaluable teaching aid. Thank you to all the feltmakers, whose workshops I have attended over the years, who have been generous in passing on their knowledge; to my students too, who have encouraged me to develop my skills. A special mention must go to Jenny Pepper for helping me to understand how to use a resist and Heidi Greb for introducing me to using raw fleece.

The lovely photographs of the finished bags were taken by Kate Stuartwww.katestuartphotography.com

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I first encountered felt in the 1980s when I saw the work of Annie Sherburne. I bought one of her kits and made some ‘interesting’ samples with an unknown variety of wool that was tricky to felt. I only slightly fell in love with the technique then, rolling with my feet in my mother’s kitchen and not fully understanding the process but loving the result. Roll on almost twenty years. Kate Bosset, a friend who had recently discovered feltmaking at a convergence in New Zealand (and had sought tuition from Anne Belgrave on her return to the UK), reacquainted me with the craft, as ‘I would love feltmaking.’ She was right. I bought some merino roving which sat in my studio for three months until I eventually struggled to interpret my scant notes, remember what she had taught me, and make some rather strange felt samples. I was hooked.

I trained as a jeweller and continue to make my living from making and selling jewellery. My work has been heavily influenced by both traditional and contemporary textiles.My three passions are colour, pattern and technique. I love making things and exploring the possibilities of different materials. I use non-traditional materials to make my jewellery, which is highly colourful and often incorporates either textiles or textile techniques. Feltmaking contrasts with and complements jewellery making so it is the perfect marriage – I enjoy working in both crafts. My feltmaking journey has had to fit in with making a living from selling my jewellery, attending the occasional workshop to extend my meagre knowledge alongside endless sessions making samples, often unsuccessfully as my ambitions exceeded my skills. The act of feltmaking is slow but meditative and cannot be rushed. In contrast with the insular nature of making jewellery, it is a sociable activity; you can make felt with people. My journey continues, as there is so much to learn about felt and its unique properties.

I have often been asked for recommendations for a good book for a feltmaking beginner to buy. It is a difficult question to answer – the longer I make felt, the more I realize what a diverse medium it is and there are constantly new developments. As finding one book to cover all of this is impossible, I refer to several books for technical reference and many more in a much broader area for inspiration. Each feltmaker works in a different way, and the way one works is also dependent on what one is making. There is never only one solution.

My aim for this book is to provide an all-round guide and instruction manual to making functional felt bags for all levels of experience. It covers the principles of using a resist to create three-dimensional forms, looks at the shapes and styles of bags to suit all occasions and works with a variety of wool breeds. Each step-by-step project expands on the earlier chapters to explain and explore the processes of design and making to produce bags fit for purpose. To fully understand these processes, read the whole book before you start. There is never an end as there is always something new to discover.

CHAPTER ONE

MATERIALS AND EQUIPMENT

Read this chapter before rushing to buy any wool or equipment. There is an immense amount of information to absorb initially, which will gradually become relevant once you start to make felt. If you understand the materials you are working with, your feltmaking journey will be speedier and your finished products more professional.

An assortment of wools.

WOOL: YOUR CHOSEN MATERIAL

Wool is a natural, sustainable resource with excellent thermal qualities and many uses. Felt is one of the earliest known textiles and is not necessarily made from wool – it can be made from various animal hair fibres such as alpaca, mohair, cashmere, camel, rabbit and beaver. However, wool felts best without the aid of any harmful chemicals.

Animal fibres felt together as their surface is covered in scales, smooth one way and rough the other. When moisture, heat and friction are applied, the scales soften, open up and link together to form a strong and versatile fabric. There are many varieties of sheep and their wool quality varies from thick and coarse for hardy sheep living in harsh climates to fine and soft such as merino that can survive in hotter weather. The length of the fibres (staple), the hardness of the scales on the fibres plus the crimp (curl) affect the ability of the wool to felt. Usually, wools with a long staple and good crimp felt well.

When I first discovered feltmaking, I had not realized that there were so many varieties of sheep, each with a delightful, fluffy wrapper. The wool of each breed of sheep has its own distinct properties. Some breeds felt well and quickly; some more slowly and with more effort; and some not at all. The quality and feel of the felt produced also varies tremendously. Some sheep are bred for meat only and their fleece does not usually make good felt. However, in the interests of limiting waste, other uses are being sought, such as insulation and slug repellent.

Like most beginners, I originally started making felt with merino wool, as it felts easily and is universally available in a good range of colours. As my fascination with making felt developed, so did my interest in the different varieties of wool. Opting to use just merino seriously limits the range of work you can produce. It is worthwhile experimenting and making samples with different breeds of wool to understand their characteristics, helping you to choose the correct breed to suit the purpose of your project. Merino might not necessarily be your first choice for making a bag. As a general rule, use a finer wool for making garments or items that are worn next to the skin that need to drape, and a coarser wool for items that need to be strong and hard-wearing, such as a bag.

Some colourful, merino wool. I try to keep similar kinds of fleece together so I can identify them easily. I store my most frequently used wool in underbed boxes so I can see the range of colours at a glance.

There are too many sheep breeds to mention in this book, and each country has regional varieties. The effort involved in sampling different breeds will expand your feltmaking skills, save you time in the long run and help you decide which wool to use for your felt projects. Understanding the characteristics of different sheep breeds will make you a better feltmaker. If you are interested in the history of feltmaking, you will find further reading in the reference section at the end of this book.

The characteristics of wool are described as a) thickness and length of fibre, b) lustre and c) crimp (waviness). The measurement in microns refers to the thickness of the fibre (the lower the number, the finer the wool) and the staple is the length of the fibre. Generally, the thicker wool with a longer staple produces a coarser and more hard-wearing felt. However, each wool has its individual characteristics (even within the same breed, depending on age, diet and climate). Some may contain thicker kemp fibres, produce a hairy finish, feel springy or lofty or have some elasticity. Others may felt really firmly, or be compact or loose. Wool with a good lustre and crimp usually felts well. If it is smooth, lacking lustre and crimp and has an even staple, it does not.

Natural wool (undyed) has a different feel, as it has not been through the harsh, chemical dyeing process and the subtle colour variations are not to be ignored in preference to the instant appeal of the multitude of colours available in dyed wool.

The more you felt, the more you will discover about this fascinating medium.

Unwashed fleece

Wool directly shorn from the sheep is dirty and will need to be cleaned to remove the dirt, dust and grease and then combed and carded so all the fibres lie in the same direction. Washing and carding fleece is a labour-intensive and physical activity and not an essential task for a feltmaker. I recommend starting with off-the-shelf, cleaned, combed and carded, pre-dyed or natural fleece.

If you are offered a whole dirty fleece fresh from the sheep, think twice before accepting it especially if you are unsure of the breed (it may not even be a good felter) or are not going to clean and card it straightaway. Dirty fleece deteriorates and attracts moths more than clean fleece.

Wool can be purchased in the form of roving (tops) and batts. A batt is lifted directly from the carding machine as loose fibres. If the batt is then combed so that the fibres are all in the same direction, it becomes a roving – a continuous rope of wool. Most wool comes in the form of roving. I will explain how to use both batts and roving in the next chapter.

Storing wool

It is tempting to overbuy when you start feltmaking and you will soon end up with a large stash. Try to avoid this, if possible. Storing wool takes up space while repeated handling of wool will matt or felt it, making it harder to use and providing a home for moths. Keeping your wool in cloth bags is best as it allows it to breathe and prevents condensation. Try to adopt a methodical method of storing your wool; keep the same varieties together and label them clearly. Although some wools are easy to identify, many are very similar. Being organized will save time in the long run and make it easy to select the correct materials for a project.

Above are suggestions of suitable wool breeds readily available in the UK. Do compare and try out your regional wools as well. Later in the book, I will explain the wool choices for each project.

Moths

It is best to buy your wool from a reputable supplier. If you have been given wool or fibre second-hand, keep it in your freezer for three to four weeks to kill any eggs. If you have freezer space, it is worth rotating and storing your wool in this way to break the breeding cycle. A chest freezer in your garage or shed is the perfect solution if you have the space. There are various products available to either deter or kill moths. Take care to follow instructions if you use any that contain harmful chemicals. For a safer approach, you may choose to use sandalwood, lavender or bay leaves, which can deter moths but not kill them. Regular checking and rotating your stash of wool is recommended to keep the creatures in check.

EQUIPMENT

A major attraction of feltmaking is that it does not require expensive equipment. Although specialist equipment is available, you might not necessarily need it, as it is easy to adapt tools you already own. Charity shops are a rich source of handy implements, such as wooden and plastic massagers. I will explain my own feltmaking techniques and why I choose to work the way I do. However, each feltmaker develops their own working methods; once you understand each stage of the feltmaking process, you can select the appropriate tools to help you achieve the desired result.

The following describes the equipment I use. You will not need all these items when you start out; I have accumulated them over time.

Ribbed rubber mat

I work on a ribbed rubber mat as a working surface for several reasons: it protects the table I am working on; it provides a non-slip surface for rolling; and you can work directly on it once you move onto the final, fulling phase of feltmaking. It is also great for making cords as, again, you can work directly on the mat. You can find suitable materials at DIY centres sold as non-slip matting. Some drawer liners have a ribbed texture which also works well. It also obviates the need to work on a towel, which can become wet very quickly and drip water on the floor.

My table ready to start work. I am an untidy person, so I try to select only the tools I need for the project in hand in order to have adequate space to work.

Plastic bowls

A selection of plastic bowls in different sizes will be useful for your spray and soap, for warming felt, for catching drips, and for transporting wet felt. (Breakable ones are not suitable, as they are easily dropped, especially when handling with soapy hands.)

Sponges, cloths and towels

Sponges are essential for mopping up any excess water, and you will find having one or two super-absorbent cloths to hand will be very useful too, especially for removing excess water from your work. Three or four old towels are all one requires when working directly on a rubber mat. A small one is handy too for drying hands between laying and wetting down the wool.

Rolling mats