28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

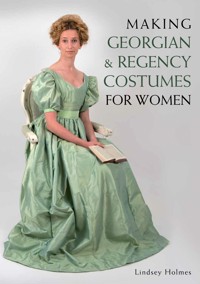

The Georgian and Regency period was a time of extremes in clothing, from the heights of the extravagant and decorative headdresses to the widths of the panniers. These garments were supported by a wide range of padding, boning, frills and flounces to create shape and texture. This essential book will guide you through the exciting fashions of the time. Suitable for experts and novices alike, it is filled with practical projects ranging from grand gowns to dainty bonnets, all presented with clarity and insight. There are ten detailed patterns, dating from 1710 to 1820 with five suggested variations to show how the patterns can be adapted; eight patterns for contemporary undergarments and seven patterns for accessories. Step-by-step instructions and photographs show how to construct the patterns and lavish photographs illustrate the finished designs. With general advice on the period, the role women played in it and the fashions of the day, this book will be of great interest to stage and screen designers, museums and heritage sites, costume players, re-enactors and design students. Lavishly illustated with 309 colour images and step-by-step instructions to show how to construct the patterns.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 244

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

MAKING

GEORGIAN & REGENCY COSTUMES

FOR WOMEN

Lindsey Holmes

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2015 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2016

© Lindsey Holmes 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 071 3

Dedication

For Geoffrey Herbert Starling, 1926 – 2014Much missed, granddad, teacher and co-conspirator in many a fanciful costume project, despite never being able to get a word in edgeways.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Part 1

1 A History of Women’s Dress 1710 to 1830

2 Tools

3 Techniques and Fabrics

4 Pattern Alteration and Fit

5 Underpinnings and Accessories

Part 2

6 Project 1: Early Mantua and Masquerade Costume

7 Project 2: Robe Volante and Caraco Jacket

8 Project 3: Robe de Cour

9 Project 4: Robe à la Française

10 Project 5: Robe à L’Anglaise and Riding Habit

11 Project 6: Robe à la Polonaise

12 Project 7: Chemise à la Reine

13 Project 8: Directoire Gown and Circus Costume

14 Project 9: Regency Gown and Spencer

15 Project 10: Late Regency Gown and Ballet Costume

16 Patterns for Underpinnings, Skirts, Petticoats and Accessories

Notes

Suppliers

Suggested Reading

Index

Acknowledgements

It takes a lot more than one person to make a project like this a reality. Meet the team that made this book possible.

Photographer: Glyn Reed, Lovelylight images

Glyn’s first darkroom was in an unlikely place, being in the corner of a rocket launch control room on board a Royal Navy Leander class frigate. Some years later and after a few photos in Navy News, he moved to Kodak. Technical support for large photo processing laboratories and training of photo industry personnel followed. Some photographic gaps and training as a teacher in later life has brought him round full circle. Exhibitions, national broadsheet press, regular pages in Rowing & Regatta, commercial work with large companies and lately an exciting project with a four-man crew planning to row across the Atlantic.

The team.

Illustrations and Retouching: Stuart Holmes

Aside from being a very talented designer, Stuart also has the great misfortune of being the author’s husband. When it is possible to escape from various unpaid jobs for his wife, he works as a landscape architect.

Stylist: Heather McIlroy

Heather has worked in fashion and retail for two decades, covering styling, visual merchandising, window displays, creating garments and homewares, and even recovering furniture upholstery. She has travelled the world, and is passionate about interiors, design, architecture and all things fashion. On the side, Heather also coxes a men’s rowing crew.

Hair Designer: Toni Tatlow

Toni began her career in hairdressing at the age of eighteen, and joined P.Kai in 2011. She is passionate about creative hair-ups, and about the art of hair. In 2014 Toni reached the regional finals of the Wella Trend Vision competition, and is also the mother of two small boys.

Hair Salon: P.Kai

P.Kai Hair opened in Hampton, just outside Peterborough, in 2002. The salon owners, Kai and Jenny, opened their smaller city-centre salon in the Victorian Westgate Arcade in 2008. The salons have enjoyed continued growth and success in the Cambridgeshire area and beyond, and have been featured in consumer and trade publications worldwide.

Make-up Artist: Rebecca Jefferson

Rebecca is a freelance make-up artist and hair stylist. She graduated from West Thames College with a BA (Hons) in Specialist Makeup and Hair, which covered areas as far and wide as intricate body paint and avant-garde hair to special effects, bridal and period work. Web: www.rebeccajeffersonmua.com.

Proofreader: Peter Starling

Although Peter is technically retired, he chose to come out of retirement to work exclusively on Lindsey’s first book, a fact that has absolutely nothing to do with his being her uncle.

Models

Georgia Delve

Georgia is a professional dancer and model with a fervent passion for historical costume and culture. Her interest in the social protocols of dance lead directly into the fashions of the ballroom, and Georgia enjoys creating period costumes for herself and for friends. She is a regular (fully costumed) attendee at Regency balls and loves to bring her historical dance-based research together with her love of costume.

Alison Dunbar

Alison studied Arabic and Middle East Studies at St Andrews University, and currently works in Glasgow. As well as extensive travel and outdoor pursuits such as hill walking, Alison also enjoys the creative arts of knitting, soapstone carving and pottery. She has a special love for the Regency and Georgian periods and wearing the dresses her great-great-grandmothers would have worn. Alison also dabbles in period millinery and dressmaking.

Camille Lesforis

Camille is a recent graduate of Central Saint Martins University, where she studied design and practice. She is passionate about creating art installations, writing children’s stories and character creation and design. Her love of period dramas and costumes inspires her work, and Camille plans to pursue a career in narrative design, and inspiring the creative skills of children through story writing.

Rachel Parton

Rachel is a costumier with over thirty years of design and making experience in costumes and props. She is a member of a medieval re-enactment group and also volunteers as a Victorian costumed room guide for the National Trust. Rachel also enjoys trying out period recipes and crafts as part of her interest in experimental archaeology.

Kirsten Stoddart

Kirsten is an Australian scriptwriter and musician, and spends her working days in film and television production offices. She is a lover of vintage and historical clothing, culture and knickknacks, and enjoys creating historically inspired events and projects for work and pleasure. Web: www.kirstenstoddart.com.

Kelly Walpole

Kelly has been passionate about the Georgian period since the age of thirteen, when she watched the television series Sharpe with her father. Since then, she has been fascinated by the people, fashions and architecture of the Georgian period, which has inspired a creative path of reenactment, balls and country dances, and an impressive wardrobe of Georgian costumes spanning from 1750 to 1812.

Bryony Woodgate

Bryony is a professional model and football blogger with a degree in Classics. She lives in London. Although she is happy to model historical clothes for her sister Lindsey, she would rather be watching the football. Web: www.toffeelady.co.uk.

Sebastian

Sebastian is a fifteen-year-old Pomeranian. He has lived in Australia, England and Ireland, and enjoys sleeping, posing, making friends and modelling his winter wardrobe.

An additional thank you to the following people for their hard work:

Costume Assistants: Jo Sandbach and Rachel Parton

Runners: Wendy Adamczyk and Laura Clappison

Props: Edie Curtis, Heather McIlroy, Kelly Walpole and Brenda Capitan

Fabric: Whitchurch Silk Mill.

I would also like to thank everyone who supported me in creating this book, especially my ever-supportive friends and family.

Korina, Bryony and Kitt model the robe à l’anglaise with front opening bodices.

Introduction

The only problem with living inside a painting is the messy business of getting in and out of that wretched frame.

18 Folgate Street, Dennis Severs1

Author Lindsey Holmes in Regency costume with a poke bonnet.

Costume has been my world now for over ten years, and I make garments that are as historically accurate as possible. This includes using handwoven cloth, hand-stitched seams and corsets with hand-picked and dried reeds for boning. I have also had to ensure that the costumes can be quick to put on, worn over clothing, machine-washable and resistant to being pulled seam from seam by fighting children.

Clothing is magical; it has the power to give us a moveable, touchable glimpse of the past. Like a painting come to life, costume allows us to peek inside the frame and explore all life through dress.

From the first moment I held an Elizabethan stomacher in my gloved hands as a student, wide-eyed and hardly daring to breathe, I knew I wanted to work with dress. I have had the opportunity not just to remake period dress but also to handle and study original items in museums all over the UK and abroad.

All of this has been fed into my teaching practice and led me to write this book, which has been designed very much with the user in mind.

How to Use this Book

My aim in writing this book is to create something both beautiful to look at and easy to use. I also want you to be able to make your own costumes by following instructions and adapting the patterns to make the designs your own. This book is divided into two parts. The first half sets out the context, giving you all of the information you should need to decide what to make and how and where to wear it. However, as it is impossible to show within this book all of the changes that have occurred in fashion over such a large and varied time frame, there is much more to learn about this period in history. If you want to do so, you could always start with the suggested reading at the end of the book, which covers many of the sources that have inspired me.

The second half of the book is a guide for making ten costumes plus a range of undergarments and accessories. I have set out each of these chapters as projects including a little history on each design and its use, together with patterns and instructions for making them.

Naturally there is a crossover between the first and second sections. Textile techniques shown in the first section are used in practice on costumes in the second section. Wherever possible I have signposted this to help you navigate your way around the book and find what you need.

All of the patterns in the book are a standard UK size 12. Chapter 4 shows you how to adapt the patterns to fit different sizes. I have done this for the models in the book as they are a range of sizes.

My construction methods are a mixture of period and modern techniques. Wherever a modern process is used, I have tried, if possible, to give the period method. However, my main aim was to create projects that are easy to follow and garments that look historically accurate for the era.

For five of the designs I have adapted the patterns to create a different look. This is to show how simple it is to create something quite different by using the same pattern. Each alternative view is based on a contemporary image. I hope you will find images that appeal to you and that inspire you to develop your own designs.

PART ONE

Chapter 1 – A History of Women’s Dress 1710 to 1830

1

One has as good be out of the world as out of fashion.

Love’s Last Shift, Colley Cibber1

Alison in a green silk Regency style dress..

The long eighteenth century (1710 to 1830) was a period of great change, both politically and socially. Many aspects of life changed dramatically and all of this change had a direct or indirect effect on the development of fashionable dress. It is just as impossible for me to cover all of the fashion worn in this period as it would be to list all of the key social and political changes. Instead I have tried to cover a few key developments to give you a taste of the eighteenth century, especially those developments that had an impact on women and their wardrobes. Much of the timeline focuses on developments in Britain, France and the Americas, and I have tried where I can to reflect the key people and developments in other countries.

A Life through Dress

Dress is special, as our whole lives can be mapped through what we wear. Clothing marks each stage of our lives, and we are judged on what we choose to wear. Viewers read our development, accomplishments, character, position and even our cleanliness from how we look. In this way we are no different from our eighteenth-century sisters, but unlike us, for many eighteenth-century women, clothes were among the few possessions they owned, and often dress was one of the few things women had any control over. Dress was a rare opportunity for women to express their individuality. This was not restricted to women of means, as cheaper items such as ribbons and handkerchiefs meant fashionable expression was within the grasp of most women.

Kings and Queens

Our timeline covers one queen and four kings. Queen Anne dies after being unable to produce a living heir and the country is left with the uncertainly of a new and unknown royal family. A similar situation is mirrored over a hundred years later when Queen Victoria takes the throne. In fact our timeline very nearly starts and finishes with a female ruler, Queen Victoria coming to the throne just after our timeline finishes. Add to this the additional upheaval of George III’s insanity and the resulting Regency period and you have a time of great unease. Changes in the surrounding royal courts of Europe and the colonies were hardly stabilizing.

Camille in a turn-of-the-century dress, reclining with a shawl.

The model is wearing a riding habit.

The Wider World

Even though eighteenth-century women looked to France for fashion inspiration, this does not mean that British fashions were the same. Not all French fashions were taken up by British women or those in the colonies, and fancy French dressing was not appreciated by many Brits. French styles put their wearers at risk of being greeted with insults as they walked the streets of London.

However, the people of France had a good deal more than fashion to worry about. At the start of our timeline France was on the cusp of financial ruin, this being due to nearly continuous wars, often with Britain. Later in the century, under King Louis XVI, a growing distance evolved between the royal family and the people, ending in the French revolution. This was followed by the rise and fall of an ambitious lieutenant colonel named Napoleon. The Americas had a revolutionary war of their own, breaking from the British Empire and declaring their independence with the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

All of this upheaval had a great impact on what people wore. Wars meant imported silks from France and cotton from America became scarcer and more expensive. War has always had an impact on fashion; military detailing and simpler lines were in part a result of the Napoleonic wars. In times of trouble many people sort solace in the details of fashion, as an aspect of their lives that they they could control. But in revolutionary France, what you wore could save you from, or send you to, the dreaded guillotine. While clothes in the streets changed a great deal, court dress, which was the formal clothing worn in the presence of the royal court, changed very little. At the start of the timeline, formal court dress would have appeared the same as the mantua in Project 1, changing to the robe de cour in Project 3, then changing to the more informal robe à la française until the Revolution took place. British courtiers, however, continued to have to wear the strange and awkward combination of Empire line bodices with pannier skirts up to the 1820s.

An Age of Enlightenment

The excitement of the Enlightenment, and the idea of reforming society by using reason, challenging the existing principles grounded in tradition and faith, and advancing knowledge through science, defines the exciting developments of this time. In many ways the modern world is created before our eyes, in a period that starts with the remnants of the dark ages and progresses towards the world we know today.

The novel as we know it today was created in the eighteenth century, and classic stories such as Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels were written. The rococo style grew outwards from Paris in the early eighteenth century and impacted on all aspects of the visual arts. Key features of the look were light colours, asymmetrical designs, curves and lots of gold. This was a reaction against its more formal predecessor, baroque. Rococo itself was overtaken at the end of the eighteenth century by the neoclassical style, which drew heavily from ancient Greece and Rome, and was complemented by similar classical fashions.

In medicine, Edward Jenner’s vaccine marked the end of the disfiguring scars of smallpox. In Britain, the annual death rate from smallpox fell during the nineteenth century from about 2,000 per million to under 100 per million. Within our own bodies, new discoveries were being made all the time. In the early years of the nineteenth century, René Laënnec invented the stethoscope and listened to the heart and lungs to help diagnose chest conditions. In 1781 William Herschel discovered a new planet outside the then known world. Some of these discoveries, such as Antoine Lavoisier’s and Joseph Priestley’s identification of oxygen in 1778, helped us to understand our world a little better. Revelations, such as the rising number of discoveries by fossil hunters, such as Mary Anning, and proof of extinction brought forward by Georges Cuvrer in 1796, increased our knowledge of the past.

Alison walking Sebastian in a polonaise, fashionable in the late 1770s.

When most people think of dress and laws, they think of sumptuary laws. These were designed to restrain luxury or extravagance, limiting who wore certain colours, fabrics or trims as well as other items. Unlike other countries at this time, England did not have any such laws in place. France did, but these were often disregarded and rarely enforced. However, laws did have an impact on what people wore in England. By the time George I sat on the throne, politicians had more power than kings, and lawmakers had an influence on every aspect of people’s lives. Laws can give us an idea of how poorer people lived. Whilst clothing could be a source of great pride, the lack of it could also be a source of great shame. In 1697 the Settlement Act required paupers and their families to wear a capital P on their clothing. Punishment for disobeying this could be the loss of relief, imprisonment, hard labour or whipping. However, given the right push the law could also provide for the poor. The Heath and Morals of Apprentices Act of 1802 applied to cotton mills and required all apprentices to be provided with two suits of clothes a year. Apprentices were unpaid and tied to their employer for a fixed term with no guarantee of a paid job at the end of their tenure, but they were provided with food and board. These were the people who helped the fabric trade to grow.

ENTERTAINMENT IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: MASQUERADE

Perhaps it was the strict rules of court life that made masquerades so popular in the eighteenth century, spreading across Europe from Italy. The freedom to disguise your identity and dress up as someone else, be it a goddess or a shepherdess, must have provided a welcome break from court life and the perfect excuse for a new gown. Much like today, many costumes of historical figures were adapted to suit the fashionable shapes of the day. To find out more, see Project 1.

A Woman’s Place

When studying women’s fashions of this time, discussion often turns to how impractical they would be to wear and how little you could do in them. This underlines a sad fact of the period that very little was generally expected of women other than as a courtly display of a man’s riches. If you think women in court dress looked little more than ornaments then you would be right, for what is practicality and comfort in the face of a display of a man’s wealth and status? Married women were by law the property of their husbands; at a time when few had a choice in whom they could marry, this could be a dangerous lottery with little chance of escape should things turn out for the worst. Most timelines of the eighteenth century are filled with great achievements by men for men. It is much harder to spot the impact women made; however, there were some very clever, brave, creative, fearless and tireless women who also had a major influence, and I would highly recommend that you research some of these. If nothing else, you will learn how hard women have had to fight for their rights and to become something more than just being what was expected of them. You will also discover and appreciate how much their achievements are still overshadowed today.

Georgia ties up her shoes ready to dance.

Fashions

Fashions moved from the great heights of the headdresses, at the start of the period, to the great widths of the panniers, and back to even greater heights of extravagant and decorative wigs, before entering a period of childlike simplicity. These changing shapes were supported by a wide range of padding, boning, frills and flounces, to mention but a few fashionable underpinnings and devices used to create shape and texture.

Despite all these changes, the shape of dresses at the start of the period already contains all of the essential elements of the classic eighteenth-century look. The bodice, overskirt and petticoat continued to be worn in different guises up until dramatic changes occurred at the end of the century. This type of costume was called the open robe, the centre front being open and showing the petticoat. The closed robe, which was worn later in the period, was almost the same but with no opening in the centre front of the skirt. This was the beginning of modern dress.

Our early mantua, the first project in this book, shows British court dress at this time. Shortly after this, large round hoops or panniers, similar to mid-Victorian crinolines, become fashionable in France. Fashion in France at this time was more informal, perhaps because of the Regency when Louis XV came of age in 1723. The large hoops could be worn with the robe volante to make it more formal. Once the hoop starts to flatten out, we start to see the beginnings of the new court fashion, born in France but with variations that were worn in many European courts. By 1740 panniers get to their widest and the classic eighteenth-century look is created when panniers are joined by the sack back and flounced lace cuffs. By the 1760s hair begins to rise and hoops are made in two folding pieces, making them much simpler to wear and move in. The Romantic movement in the 1770s, with its emphasis on the simple and natural, was complemented by the fitted and newly closed English gown: the robe a l’anglaise, and the robe à la polonaise with its looped-up skirt and shorter petticoat. Pads started to replace hoops, and Marie Antoinette’s chemise à la reine lead the way to the new simple Grecian look at the end of the century. The simple floor-length gowns with long trains, fitted bodice with high waists and short puff sleeves resemble children’s dress. By 1815 this new simple style is established, with shorter and wider skirts, more frills and the Spencer jacket and poke bonnet. As we approach the end of our timeline, the classic Regency look starts to transform into the early Victorian style, and hence our last project shows the lowering waistline, the skirt continuing to widen and the sleeves starting to grow, ready to become the next outlandish fashion. The eighteenth century really was a period of extremes.

ENTERTAINMENT IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: A SPORTING LIFE

Life in eighteenth-century England was typified by the landed gentry staying at their county manors away from court life and enjoying a simple and practical outdoor lifestyle. Nothing typified this more than the English woollen riding habit. When it became fashionable in France to dress à l’anglaise, this was the costume to have. This is perhaps one of the most masculine and practical outfits a lady might have in her wardrobe at this time. To find out more, see Project 5.

Georgia reads in a silk evening gown.

Shopping

Although you could now go to a shop and buy fabric and ribbon, go to a mantua-maker and have a dress made for you, or even buy some items off the peg, the process of fabric to fashion was very different to what we know now. Many of the things we take for granted today simply did not exist at this time. There were no sewing machines, every stitch was completed by hand and the women making the stitches had only daylight or candlelight to work by. Labour was cheap and easy to come by, whilst fabric was expensive and precious and the sort of thing you would pass down in your will. Naturally this impacted on how garments were made, with stitches often designed to be easily undone so that the fabric could be reworked into something new.

Fabrics

Perhaps one of the things that most impacted on our theme is the development of fabrics and the increasing mechanization of textile production. This change allows fabric production to leap forward, with it becoming much faster and more detailed and providing a greater choice of materials.

Traditionally, Britain traded in wool and linen. The output of woollen cloth increased dramatically over this period, supported not just by developments in the weaving process but also by the popularly of tailored garments for both men and women, at home and abroad. Linen was the staple cloth for everything, from undergarments to aprons, and hats to stockings, but cotton was soon to rival linen, starting with printed gowns and working though the whole wardrobe. Other fabrics followed, with an influx of Protestant weavers from France fleeing persecution and creating a unique opportunity and a new industry in silk.

Our timeline covers a period of growth in silk weaving in Britain. This was further boosted by the ban of imported silks in 1773. The fact that silkworms could not be cultivated in Britain kept prices high, and meant that the raw materials still had to be imported. The beauty of the final project could stand in stark contrast to the misery and poverty of its makers as industrial action on hours, pay and a lack of government support occurred. This was a consistent feature throughout the period. However, the industry could offer women new and better-paid jobs, which was something they were quick to take advantage of:

To dress in the greatest extravagance, so much so that on a Sunday those who formerly moved in the most humble social sphere and appeared in woollens and stuffs have lately been so disguised as to be mistaken for persons of distinction.

English Country Life, E. W. Bovill2

At the start of our timeline cottons are available but expensive, as they are imported from India. Later, once they start to be woven and printed in Europe, the development of cheaper printing processes made printed cottons available to a wider clientele. Their popularity then increases as their cost drops. By the end of the eighteenth century cotton has stolen silk’s crown as the fashionable fabric, and silk weavers are copying popular printed cotton designs. In 1820 the annual average value of cotton exports from Britain was £28,000. This is equivalent to over £1.5 million in today’s money. Samples from the vast collection at the Foundling Museum show that even the poorest women had access to colour and prints. Even if they could not afford the fabric for a new dress, ribbons were a cheap and easy way of dressing up an outfit.

The correct way to stand with the arms neither forwards nor backwards nor too close to the body.

The correct way to give or to receive.

The proper behaviour in dancing.

Giving one hand in a minuet.

Giving both hands in a minuet.

Manners and Etiquette

Dress, manner and carriage are just what she wants, a person must be a great beauty to look well without them, but they are certainly within the reach of any body of understanding.

The Letters of Fanny Brawne to Fanny Keats 1820–1824, Fanny Brawne3

The meaning of manners and etiquette are not so clear-cut today as they were in the eighteenth century; etiquette is perhaps the concept we come across the least today. Etiquette is a code of behaviour that dictates expectations for social behaviour according to contemporary norms within a society, social class or group. Manners are a person’s bearing or way of behaving towards others, and whether the way in which a thing is done is socially acceptable or not.

During the long eighteenth century, knowledge of these standards and behaviours was a symbol that you were a genteel member of the upper classes. Everyone wanted to be accepted and aspired to reach the next step of the social ladder. This developed into an obsession about the precise rules of current etiquette. By the end of our timeline – the start of the Victorian era – etiquette had developed into a complex system of rules, covering everything from the smallest to the largest duties and interactions, that was do deep-rooted it took a world war to break them down.