13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

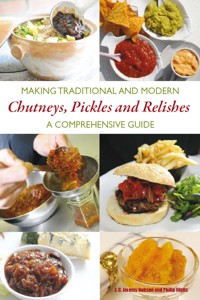

Chutneys, pickles and relishes are important forms of preserved food that can bring life and richness to any meal, be it a simple lunch or an exotic dinner. Commercially, they form a multi-million pound industry and ever-imaginative new examples appear on the supermarket shelves with great regularity. Moreover, pickles, chutneys and relishes are often a favourite with shoppers at farmer's markets and country fairs. Notwithstanding this, there is absolutely no reason why, with very little effort, and often the most basic of locally sourced ingredients, you should not make your own.The superb chutneys, pickles and relishes presented in this book have resulted from the authors' extensive research that has brought them into contact with modern-day restaurant chefs and prize-winning traditionalists. If you enjoy fresh, tangy flavours, then this book will provide you with all the help and inspiration you need to enter the world of successful chutney making and pickling. As for relishes, once you, your family and friends have experienced some of what is on offer on these pages, it is possible that you will never be content to settle for the shop-bought versions again.An inspirational guide to making traditional and modern chutneys, pickles and relishes using time-honoured recipes and also twenty-first century variations.The authors spent time researching, photographing and meeting with both modern day restaurant chefs and prize-winning traditionalists.By experiencing some of these tempting recipes, it is unlikely the reader will settle for shop-bought bottles again.Beautifully illustrated with 60 colour photographs.Jeremy Hobson is a prolific freelance writer on all matters 'rural' and author of over twenty books on country life.Philip Watts' love of both cuisine and photography led him to a new career as a food photographer.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 201

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

MAKING TRADITIONAL AND MODERN

Chutneys, Pickles and Relishes

A COMPREHENSIVE GUIDE

J. C. Jeremy Hobson and Philip Watts

Copyright

First published in 2010 by The Crowood Press Ltd, Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book edition first published in 2013

© J.C. Jeremy Hobson and Philip Watts 2010

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 978 1 84797 502 7

Photography Acknowledgements Unless otherwise indicated, the photographs in this e-book were taken by Philip Watts and are his copyright. The authors and publishers are grateful to Rupert Stephenson for providing one additional photograph.

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Acknowledgements

An Introduction and the Overseas Influence

1 Utensils, Hygiene and Storage

2 Choosing the Right Ingredients

3 Recipes for Characterful Chutneys

4 Recipes for Pickles and Pickling

5 Recipes for Relishes, Ketchups, Marinades and Dips

6 How to Use Chutneys and Pickles

Glossary

At a Glance Recipe List

Index

Acknowledgements

As always, there are several people to thank in connection with the compilation of this book, not least of whom are Lawrence and Julia Murphy, Fat Olives, Emsworth, Hampshire; Chris and Sarah Whitehead, Whites@the Clockhouse, Tenbury Wells, Worcestershire; and Jonathan Waters, also at Whites@the Clockhouse, Tenbury Wells, Worcestershire. Special thanks too must go to Lynn Brodie and Mary Hart – the latter of whom was kind enough to let us riffle through her considerable recipe stocks and include many of them within the pages of this book.

Others who have helped tremendously in supplying recipes and in all sorts of other ways are (and in no particular order) Beryl Woodhouse; Mariangela Karlovitch, the Medusa Resort Hotel, Naxos, Greece; Valerie Hardy; Samantha Coley; Ann Lambert; Ann Brockhurst; Kathy Neuteboom of Stonham Hedgerow Ltd, Ipswich, Suffolk (www.stonhamhedgerow.co.uk); Chris and Felicity Stockwell; Sally Hallstead; the Country Women’s Institute of Australia; Alexios Theophilus; Theo Cartwright; Andy Hook at BlackfriarsRestaurant, Newcastle; Robin Harford of www.EatWeeds.co.uk; Hall & Woodhouse, family brewers, Blandford St Mary, Dorset; Edd McArdle; Simon Adams and Rosie Robinson who were, at the time of writing, at The Stephan Langton, Friday Street, near Dorking, Surrey; Michael Stamford; Andrew and Jacquie Pern at the Star Inn, Harome, Helmsley, North Yorkshire; Stella Boldy and Doreen Allars.

We have particular cause to be grateful to Tom Stobart’s book, The Cook’s Encyclopaedia: Ingredients and Processes, published by B.T. Batsford in 1980 – without it and its particular definitions we would have not found compiling our book quite so easy. Thank you to Lucy Smith of Anova Books for granting permission to quote from its pages. Thanks, too, to Louise Bilham of the rights department of ITV plc for using all her efforts to gain permission to include the recipes that first appeared in Farmhouse Kitchen II, published in 1978 by Trident International Television Enterprises Ltd.

AUTHORS’ NOTE

It has obviously been impossible to test every recipe included within these pages. All have, however, been offered in good faith by well-respected chefs: the winners of various trophies at relevant events large and small, amateur cooks, enthusiastic family members and friends, all of whom assure us that their recipes work. Sometimes, however, they have been a little lax in their quantities or methods and, rather than imposing upon them again for yet another favour, we have used our discretion in order to make logical assumptions regarding weights, alternative ingredients or cooking times. The making of country chutneys, pickles and relishes is not, after all, an exact science – a point which the newcomer to this method of preserving should always bear in mind.

Also, whilst not doubting in any way their veracity, we cannot guarantee that any recipes given by anyone have not been adapted from those that have already previously appeared in books or on the Internet (bearing in mind the fact that many ‘classic’ recipes have, over a period of time, come into the public domain). Therefore, should anyone reading this book feel that their own recipes have been taken without permission, we can only offer our apologies and the promise that, if they contact us via the publishers, we will make suitable amends in any future reprints.

WEIGHTS AND MEASURES

Some of the older recipes included in this book have been converted to metric from imperial; a practice that cannot be carried out precisely. For instance, 1oz is actually equal to 28.35 grams, so it is not really possible to measure accurately 25 or 30 grams if you are using imperial measuring spoons, jugs and scales. The same applies to liquid measurements, so, in order to avoid complications, we have in some instances rounded the conversions up or down.

AND FINALLY …

The mention of any products, or manufacturers of products, in the text does not in any way mean that they have our endorsement!

J. C. Jeremy Hobson

Philip Watts

Summer 2010

A row of chutneys and pickles makes you look forward to the next occasion they can be used!

An Introduction and the Overseas Influence

Living in the rural countryside, ‘Granny’ did, quite often, know best when it came to preserving summer and autumn produce in order that it could be safely eaten all year round. Worldwide, chutneys, pickles and relishes were created, not only to use up surplus fruit and vegetables, but also to mask the taste of meat and fish that may have been past its best, or to spice up what might otherwise have proved to be a bland and boring meal. In all its various forms and for whatever reason, creative chutneys and pickle-making was a practice that began many, many generations ago – although it proved to be particularly important in some of the more austere years of the twentieth century, when food was hard to come by and what was available needed the addition of something to make it more interesting. (Yes, even the eating of wartime luncheon meat was apparently made almost pleasurable by the inclusion of a spoonful or two of chutney – which did, however, have the effect of making chutney less popular after World War II because it brought back memories of hard times.)

During the final, wealthy decades of the twentieth century, however, the Western world possessed more money than possibly ever before and it became, on the whole (with the exception of a few diehards), pretty much a ‘throwaway society’, with the result that it was almost unthinkable that anyone would bother making their own chutneys, pickles and relishes, when there were some perfectly acceptable and certainly more easily obtained examples to be found on the supermarket shelves. However, since then, various financial crises, the need to cut down on air miles, an increasing interest in smallholding and a desire to get ‘back to nature’ – together with the popularity of attractive produce being seen by those who would like to use it properly and frugally – have brought some of both Granny’s principles and Far Eastern cooking techniques back into vogue.

Modern-thinking cooks with a view to the countryside and the sourcing of local produce have not missed any opportunity to utilize traditional recipes and, in some circumstances, have even given them a modern and exciting twist. Recent interest in the art and skills associated with making pickles and chutneys has ensured that the relevant classes in the ‘produce’ sections of village and county shows no longer merely contain a few pots produced by the older generation of stalwarts, but are now also enthusiastically supported by much younger contestants of both sexes. Farm shops report that, when customers come in to stock up on fresh vegetables, they almost always peruse the shelves containing attractively packaged pickles, chutneys and relishes and, having done so, invariably take one or two jars away with them.

Has anyone failed to be pleased with a small Christmas hamper of pickles and chutneys? We don’t think so – okay, they might not have quite the same cachet as a De Beers diamond or the keys to a Ferrari, but they will, nevertheless, be brought out and enjoyed during the following few weeks and months. Home-produced pickles and chutneys will therefore make perfect small gifts, especially if presented in unusually shaped or pretty containers that are pleasingly labelled – not a difficult job in these days of computer-design programs.

Home-produced chutneys and pickles look even better when they are attractively labelled and pleasingly packaged.

As well as being given as gifts, pickles and chutneys make useful additions to any charity fund-raising event and will, like the ones on display in the farm shop or at the farmers’ market, soon disappear from the table top from which they are being sold. So, selling pickles and chutneys is no longer the preserve (forgive the pun) of the Women’s Institute or regional branches of the Townswomen’s Guild. There are, however, as with so many things appertaining to modern living, certain legalities to which one must adhere when making and selling produce for public purchase and consumption. It will therefore pay to check whether, in order to do so, you need to have your ‘production premises’ inspected by environmental health officers and any weights and measures approved by trading standards. Remember that all local councils are different. Making chutneys and pickles to sell for profit requires much the same approach (and may also require you to be registered with the local council), but could be well worthwhile in the long run. While farmers’ markets were originally set up to provide local farmers with a direct outlet to the public, the National Farmers’ Retail & Markets Association (FARMA) is also keen to encourage what it jargonistically terms ‘non-farming secondary food producers’.

There are certain legalities to which one must adhere when making and selling produce for public purchase and consumption – even at the most local of affairs.

THE OVERSEAS INFLUENCE

Defining pickles is reasonably straightforward, which is more than can be said for identifying the exact differences between what is a chutney or a relish, where there can be an element of crossover – as will be seen later in this section and also in the main chapter dealing with recipes. Basically, pickling is simply a method of preserving food by immersing it in brine or vinegar. There is some evidence that the word pickle is derived from the Germanic word pekel, meaning ‘brine’, but it is also known that the word was in existence in the English language of medieval times when it was variously spelled as pekille, pykyl, pekkyll, or pykulle. Although it would not have been known as such, the actual method of pickling has been used since at least Roman times as a means of preserving fruit and vegetables during times of a glut. Cleopatra, Pliny, Julius Caesar and Tiberius were, according to the writings of the Ancients, all avid consumers of pickles (in far more recent times, Napoleon insisted that his catering corps carried portable, preserved fruits and vegetables with which to feed his invading armies).

Despite now being associated with traditional and regional UK foods, especially cold meats and, latterly, the ubiquitous pub ‘Ploughman’s Lunch’ (which is, incidentally, a creation of some 1960s adman’s imagination rather than, as is often supposed, a centuries-old farmer’s hunger-beating standby), chutneys actually originated in India and were first mentioned in British cooking books in the 1600s. The name is a derivation of the word chatni, which was used to describe a strong, sweet relish, but in particularly old books it is often written as chutnee. Its appearance in Britain and elsewhere came about as a result of the development of trade with India; ideas and cooking methods had been brought home, but the ingredients altered in order to make use of whatever produce was available locally (a sentiment that should apply equally to today’s chutney makers). Experts agree that there is a huge difference between what is known as chutney in India and surrounding countries (normally a mixed paste of raw, freshly harvested and ground ingredients) and the much sweeter tasting (cooked and preserved) chutneys found in the Western hemisphere. Somewhat confusingly, any Indian traditionalist tasting such a chutney would probably describe it as a sweet pickle!

The Ploughman’s Lunch is a creation of some 1960s adman’s imagination rather than, as is often supposed, a centuries-old tradition.

And the confusion doesn’t stop there, as what we call a chutney in the UK might be referred to by an American as a relish! When the various people involved with this book were questioned as to what they considered to be the essential difference between a chutney and a relish, most of them simply described a relish as being thin chutney – which is no real help at all! Further research, however, indicates that relishes are made in different ways throughout the world and many are, in fact, a cross between a pickle and chutney. Others are thickened by flour and made creamy by the inclusion of local yogurt. Perhaps the easiest definition to give is that relishes were, in their original form, accompaniments to a main meal, or were a type of cooking marinade, and were often made at the last minute using whatever ingredients were available. Being fabricated from freshly gathered produce and having little or no preserving ingredients included, they obviously had limited ‘shelf life’. Relishes are perhaps best known in America, where they undoubtedly originated as a result of Mexican and Spanish immigrants bringing with them traditional salsa recipes. Incidentally, even accepting that the word salsa is basically a Spanish word for sauce, it is impossible to understand why the same word should be used to describe a kind of dance music of Cuban origin – perhaps it’s because the elements of jazz and rock music encourage a ‘saucy’ dance from the participants?

Think of America and one cannot help but imagine commercially produced tomato ketchup being spread in great, unnaturally coloured globules of gunk on top of a burger, but it is only in the West where the name has become synonymous with such eating habits. In Javanese cooking, for example, ketjap is a type of soy sauce, which quite often includes a salty fish base and either molasses or brown sugar. Other sources have it that the word ketchup is derived from the Chinese language. According to Tom Stobart writing in The Cook’s Encyclopaedia, the cookery books of the nineteenth century abounded with ketchup recipes – oyster ketchup (oysters with white wine, brandy, sherry, shallots and spices), mussel ketchup (mussels and cider), pontac or pontack ketchup (elderberries), Windermere ketchup (mushrooms and horseradish), wolfram ketchup (beer, anchovies and mushrooms) and others based on walnuts, cucumber or indeed, almost any other ingredient that happened to capture the cook’s imagination.

ALL ROUTES LEAD TO HOME

No matter from where they might originate, pickles, chutneys and relishes are known worldwide – so much so that in Australia the word ‘chutney’ was used as a metaphor in ‘Chutney Generations’, the world’s first ever exhibition tracing the extremely complex Fiji-Indian identity, which was staged at the Liverpool Regional Museum in Sydney from December 2006 to February 2007. In the context of the exhibition, it compared the fusion, culture, dreams, ideals, ideologies and history of Fijian-Indian migrants across the globe as being similar to the process of making chutney, that is, where ingredients are blended to the point where there is no single identity (an arguable notion when one considers that all of those we have met in connection with this book insist that every single one of the ingredients of chutneys should complement one another). Not content with such a simile, the organizers of the exhibition went on to coin a new word, describing the coalition of the Australian-Fiji-Indian community as being a ‘chutnification’!

At the other end of the world, there is, of course, the traditional pickled herring to be found in Norway. Less well known is the fact that Norwegians have a recipe for poached cod – which is apparently best served with a green tomato pickle. In-between, the African continent has a whole plethora of mainly vegetable-based relishes, many of which started life in the seemingly inhospitable Sahara, and also includes the Tanzanian speciality of horseradish relish, traditionally served with boiled beef – not too far different from England’s long-established Sunday roast.

Norwegian pickled herrings.

We might be pushing the connection, but there’s also the question of coleslaw being a type of relish. The basic description is that it is simply a salad consisting mainly of shredded raw cabbage, but there are several variations, many of which include typical chutney, pickle, relish and dip ingredients and need the addition of oil and vinegar to make them work.

Reading Making Traditional and Modern Chutneys, Pickles and Relishes will, we hope, turn you from being perhaps merely an interested bystander into an enthusiastic and dedicated participant of an age-old science, which has, once again, come to the forefront of modern cooking. If you enjoy the country life and can participate in it by growing some of your own produce, all well and good. If you live in the town and source your ingredients via the High Street greengrocer or through weekend trips to market towns, pick-your-owns or even from the hedgerow, you will not be disappointed by the recipes included here. Wherever you live and no matter how they are produced, we guarantee that, every time you open your cupboards and see a batch of jars or bottles catching the light and glowing full of autumnal colour, you will smile and look forward to the next occasion they can be used.

Utensils, Hygiene and Storage

Making chutneys, pickles and relishes is not, to use today’s jargon, ‘rocket science’. It is a cost-effective thing to do, requiring very little in the way of specialized equipment and ingredients, which, when chosen for their seasonal availability, should be cheap enough, or even free. Nevertheless, there are some basic cooking and preparation utensils required and also, for obvious health reasons, a certain understanding of the need for hygiene in preparation, bottling and storage. But it is all extremely therapeutic, even ritualistic: old jam jars and pickle pots are retrieved from where they’ve previously been stored, washed in the sink, then sterilized in the oven; preserving pans are removed from the top of the kitchen cupboard (and the resident spider made homeless); funnels and wooden spatulas are recovered from whatever job the children have been using them for; and, finally, a decision has to be made as to what recipe best suits the surplus produce currently on offer. Oh, and then there’s time, of course; it can be a long process, so it’s as well to be sure that you have everything to hand before you start.

UTENSILS

Although some of the equipment necessary is quite specialized (a decent preserving pan, for instance), much of what you need, such as wooden spoons, will already be part of the contents of the average kitchen drawer. Anything that does need to be bought will, however, be relatively easy to source. Look in the right shop dealing specifically with such items and you should be able to find all the tools, utensils and storage equipment necessary to pickle produce and make chutneys at any time of the year. In other retail outlets, they seem to be a seasonal addition to the shelves and appear just in time to coincide with the ‘season of mists and mellow fruitfulness’, as described by John Keats in his poem of 1819, Ode toAutumn. Some of the best places to look for specific equipment are your local garden centre or country store. If you happen to be visiting France, or, in fact, any European country where the art of preserving surplus fruit and vegetables is a regular part of rural life, the hypermarket there will also prove to be very useful. Of the specialist outlets in the UK, it appears, from talking to several people in connection with this book, that Lakeland Ltd is a firm favourite. Lakeland prides itself on being ‘the home of creative kitchenware’ and, judging from the content of its High Street shops and online ‘virtual catalogue’, we see no reason to disbelieve the claim.

It is best to have all of your likely equipment and ingredients to hand before making a start.

POTS AND PANS

Not many households will have a large enough cooking pot for making vast quantities of chutney, therefore the acquisition of a suitable vessel will be essential. It will also undoubtedly be your largest financial outlay, so you might as well buy the best to start with. If it is manufactured and sold expressly for the job, there will be no concerns regarding the material from which it is made, but otherwise it is best to ensure that it is stainless steel or aluminium – there are devotees of both. Other materials – iron, copper or brass, for example – could cause whatever it is you are preserving to become tainted. Enamelled pans are recommended by a few, but dismissed by many, because of the fact that they will eventually become chipped and therefore difficult to keep clean and sterilized.

Whilst big heavy-bottomed saucepans can be used, one of the problems of doing so is that because they are generally straight-sided, air flow is restricted, cooking takes longer and there is more chance of the pan’s contents becoming burnt. Preserving pans are typically wider at the top than the bottom and, depending from what material they have been made, might be ‘double-layered’ or ‘encapsulated’. Stainless steel, for example, is known to be a poor conductor of heat, so an encapsulated base (where a disc of aluminium has been sandwiched between two stainless-steel discs on the bottom) will make heat conduction that much more effective. Stainless steel is also attractive to look at (and, due to its size, your pan might need to be on permanent display rather than tucked away in a kitchen cupboard), easy to clean and maintain, robust and long-lasting. Choose a pan that is easy to use; some have bucket-type handles, with further aid being given by the addition of a smaller ‘helper’ handle attached to one edge.

A decent-sized preserving pan is essential.

There is generally never any need for a pan to have a lid, as the contents of preserving pans are usually cooked with the lid off. Leaving a lid on chutney whilst cooking will simply cause condensation and resultant water, whereas the idea should be to allow liquid to evaporate slowly during the heating process.

With relishes and the like, the quantities and volumes will be much smaller, so almost any good quality heavy-bottomed pan that fits the above criteria will suffice. There is also the obvious difference between the cooking times of chutneys and relishes, the latter being cooked for very short periods, so a robust pan is not quite so necessary for relishes.