13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

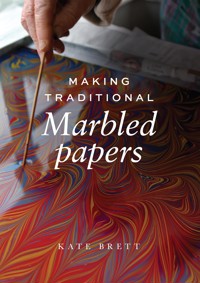

Paper marbling is a beautiful craft with a long history that can be traced back to Japan in the twelfth century. This practical book introduces traditional patterns and explains the techniques that are used creatively today. It covers the history of marbling – from its origins in Japan to Persia, Turkey and then Europe in the seventeenth century. Details on equipment and materials are given along with what you need to get started and to set up a studio. The process from preparing the size, to adding the paints, creating the pattern and then treating the sheets is covered in detail. It introduces traditional patterns such as spot and combed patterns, as well as advanced techniques. Creative uses for marbling are given including step-by-step sequences for a range of projects. Making Traditional Marbled Papers is a visual treasure and shows how paper marbling can be practised and appreciated by all, from children to professionals.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 134

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

First published in 2021 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

© Katherine Brett 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 958 7

Cover design: Sergey Tsvetkov Photographs and illustrations: Blythe Brett

Acknowledgements

With many thanks to Nick Abrams, J. & J. Jeffery (bookbinders and paper pattern makers extraordinaire), Jake Benson, Kubilay Dinçer, Barry Brignall, Chris and Sarah Shaw, Ola Søndenå – University of Bergen Library, Asa Henningsson – Uppsala University Library, Linda Sorensen – National Library of Sweden, Peter Wärmling, The Schmoller Collection, Anne Ullmann, Anil Goutam – Rahis Papers, Solveig Stone, William McCracken, Richard Renouf, Beth Scanlon, Rosi de Ruig, and enormous thanks to my daughter Blythe, without whom I could not have put this book together.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

1 PAPER MARBLING STYLES

2 EQUIPMENT AND MATERIALS

3 THE PROCESS

4 MAKING SOME TRADITIONAL PATTERNS

5 USES AND APPLICATIONS

6 NOTABLE MARBLERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

SUPPLIERS AND COURSES

INDEX

INTRODUCTION

The thousand-year-old craft of marbling is alive and well, and it can be practised and appreciated by everyone, from children to professionals. There are various different methods of marbling, and it can be used in commercial trade, as the basis for artistic or academic study, or as a source of relaxation, therapy or fun.

Endpapers from early eighteenth-century books, showing the colours generally used in early marbling – Indigo, Red Lake, Yellow Ochre and Lamp Black.

The Placard – a very early pattern first created and used for book decoration in France between 1680 and 1740.

Marbling is the name given to the creation of designs and patterns on the surface of a liquid, which is then transferred onto paper or other materials. This book will concentrate on marbling paper in the traditional way, which is an old process using water-based paints floating on a jelly or ‘size’. In this book I will particularly concentrate on the history and making of marbled papers in Britain, and on the traditional patterns that are still popular today.

A Brief History of Marbled Paper

Historically there are two basic marbling traditions.

The first was found in Japan as early as 1118, and known as suminagashi. This was made by floating drops of ink on water, then a sheet of paper was placed on top and the design was transferred. These papers, apart from being works of art in their own right, were used as a background on which to do calligraphy and also as a unique security measure for documents. Suminagashi represents marbling in its initial and simplest form.

By the 1400s, the Iranian élite began migrating to the Deccan plateau of south India, where a new marbling tradition began. Lured to the region for many reasons, these poets, traders, statesmen and artists of all kinds left an indelible mark on the Islamic sultanate that ruled the Deccan until the late seventeenth century. By 1600, one Muhammad Tahir, an enigmatic Persian artist and émigré to India, was producing highly innovative marbled papers with intricately worked combed designs, used as borders for paintings or calligraphy (from Iran and the Deccan, Jake Benson, Indiana University Press, 2020). Deccan marbled drawings are occasionally illustrated, and an elaborate technique was developed using stencils outlined in gold, with painted faces added to complete the work. The marbling on these documents and figures is of a very high standard. These methods of marbling quickly spread from India to greater Iran and the Ottoman Empire.

A page from Qit’at-i Khushkhatt – a Persian album of calligraphy and marbled paper, with marbled papers by Muhammad Tahir, c.1600. (Photo: University of Edinburgh Library)

Evidence demonstrates that Turkey was the conduit by which marbling arrived in Western Europe. A fledgling decorative paper industry emerged among professional stationers in Istanbul during the mid-to late sixteenth century. As early as the 1570s European travellers to Istanbul purchased these colourful ‘Turkish papers’ and had them bound into small friendship albums (alba amicorum). These early sixteenth-century papers had rudimentary stylized drop-motifs and primitive spot patterns and have a distinctive smell of curry because the size that was involved in their making was extracted from fenugreek seed. Some of the albums containing old marbled papers still carry this distinctive smell because fenugreek was used as a size on which to float the colours in India and also in Persia.

Pen copy of the engraved portrait of the Earl of Northampton, c.1599, ascribed to T. Cockson. Pen and black ink on marbled paper. (Photo: Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge)

The earliest English description of marbled paper appears in 1615. George Sandys, who travelled in the Islamic world in 1610, wrote that ‘they curiously fleek their paper, which is thicke; much of it being coloured and dappled like chamolet; done by a tricke they have in dipping them in the water.’

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries marbled patterns became more controlled and the water on which the paints were floated was thickened. Natural thickeners were used to create the jelly or ‘size’ on which the paint patterns were created. Size ingredients such as gum tragacanth became common later.

Marbled papers became a popular covering material not only for book covers and endpapers, but also for lining chests, drawers and bookshelves. The marbling of the edges of books was also a European adaptation of the art. The golden age of marbling in France and Germany ran from the 1680s until the 1730s/40s. The patterns produced there were rather beautiful and formal in their design.

By the middle of the seventeenth century marbled paper had made its way to Britain. Goods were imported from Germany through Holland – the Dutch acted as commission agents, buying and selling goods that they reexported. Marbled paper was first brought into England as wrappings on parcels of toys from Holland in order to avoid the heavy English duty tax on paper. Hence some of the earliest papers found in Britain are known as ‘Old Dutch’. The art did not fully blossom in Britain until the 1770s, and from then on it had a strong and energetic existence for the next fifty to seventy-five years.

An early example of the wide combed pattern that became known as Old Dutch.

The first known manual devoted to marbling was The Whole Process of Marbling Paper and Book Edges by Hugh Sinclair, who was making marbled paper in Glasgow around 1815. The major part of his manual was devoted to specific directions for three early patterns: Antique Spot (or Turkish), Stormont and Shell. Secretiveness was very prevalent at the time – marblers who worked in binderies tended to erect partitions to keep their marbling methods secret.

A very early example of an Antique Spot pattern shown in The Poetical Works of Christopher Pitt (Edinburgh, 1782).

A very early Stormont pattern found in the endpages of Cary’s New Itinerary of the Great Roads, both direct and cross, throughout England and Wales, 1806.

Sinclair used gum tragacanth as a medium for marbling and this continued to be used for most of the nineteenth century. The earliest and most common patterns produced by British marblers from around 1750 were the Antique Spot, Stormont and Shell patterns. Eventually marblers began to intermix the Shell and Stormont patterns with some beautiful results.

During the 1820s English makers revived the waved pattern that had been popular in Spain at the end of the eighteenth century. The British produced this pattern more precisely with very even lines of waves. Not long after this, the small combed pattern that came to be known as ‘Non-Pareil’ was introduced. These patterns were the stock-in-trade of British marbling throughout the nineteenth century.

This is an early example of marbling in Spain from Día y Noche de Madrid, published in Madrid in 1766. It shows characteristic soft colours, with waving that is charmingly irregular and in wide bands. (Photo: Ola Søndenå, University of Bergen Library)

A marbled endpaper using French Shell, from The Topography of Athens, bound in London in 1835. (Photo: Ola Søndenå, University of Bergen Library)

In 1853 a detailed description of marbling methods was written by Charles Woolnough – The Whole Art of Marbling was the first English work on marbling to be illustrated with specimens of the patterns he was describing and showed their progressive stages. Marbled paper also appeared in Laurence Sterne’s novel Tristram Shandy (1759), one of the first published books to use it.

In the 1830–80 period the introduction of mechanization into bookbinding brought about a decrease in the use and production of handmade marbled papers. Then in the 1880s there was a revival that can be attributed to Joseph Halfer, a bookbinder of Budapest. He introduced new materials and methods based on sound scientific research and wrote Progress of the Marbling Art (1885). Halfer’s discoveries published in this book made an impact that revolutionized the craft and jolted it out of the rut it had fallen into with so much factory-produced marbled paper. He advocated using carrageen moss for the ‘size’, which although known of earlier was not popular because it did not keep as well as gum tragacanth. Halfer was a chemist and worked out that adding borax to the carrageen would enable it to be kept for months. A number of highly advanced masters took up this new form and style of marbling, which is based on the production of clean, bright and detailed comb work.

A combination of Stormont and Spanish Wave from the early nineteenth century.

An advertisement for the Halfer Company Marbling Supplies. Halfer kits were available in England from at least 1890.

By the early 1920s British marbling was in a tired state, but with the production of marbled papers by Sydney ‘Sandy’ M. Cockerell it began to revive. Cockerell set new standards and published a booklet, Marbling Paper (1934), which brought the craft before a wider public and raised its status. Cockerell papers were made according to pure Halferian methods and they were produced to a high degree of perfection. His studio introduced devices that enabled complicated patterns to be repeated accurately. This mechanization meant that Cockerell papers could be made and distributed far and wide, raising the awareness and popularity of marbled paper once again.

Today handmade and traditional crafts have seen a surge in popularity and marbling has become better known. On a large scale it can be labour-intensive and is still a tricky craft to get to grips with, so not many individuals take it on full time. It is more common as a small-scale hobby or creative pastime.

EBRU

Abri is a Persian term meaning ‘clouded’, as in ‘clouded paper’. The Turks adapted this word to call their marbled papers ebru in 1831. Ebru marbling is still popular in Turkey today and they are the masters of marbling flower and animal motifs, using a stylus to move the paint around.

My Involvement with Marbled Papers

Marbling can be enthralling and exasperating in equal measure. It is difficult to predict exactly what will happen when the colours hit the size. Most of my work is in producing papers for publishers or bookbinders, who may want large numbers of sheets to use in a publication as endpapers or covers. Although this sounds monotonous, it is still very rewarding when everything behaves as it should and the pattern produced is close to the original sample.

Me in my studio in Edinburgh in 1985.

My interest in marbling began when I took a course in ‘Fine Bookbinding’. Coming across marbled papers in old books, I was enthralled by the beauty of the marbled patterns. Then followed many months of trial and error, frustration, and much experimenting with different methods and mediums. There was nowhere to go to learn marbling at that time, nothing like a workshop. Marbling is constantly changing and has always been a challenging art form – I remember being thrilled when after some months I managed to get the paint to float on the carrageen size. I was boiling up great vats of carrageen seaweed in my studio, and after the jelly had been extracted I poured the used seaweed onto any plant needing sustenance in my garden. One of the early booklets I consulted was the one by Sandy Cockerell entitled Marbling Paper (1936) so, with the help of this and another pamphlet by the Dryad Press, I persevered.

My current studio in Cambridgeshire.

The first papers I designed were small speckled patterns, which I thought might be good for using on small books. Gabrielle Falkiner of Falkiner Fine Papers in London’s Covent Garden was very encouraging and placed an order with me for 200 sheets, much to my astonishment. As I started to feel slightly more in control of the process, I began to experiment with producing other patterns, particularly the traditional ones such as Antique Spot, Old Dutch and French Curl. Trying to produce these types of traditional patterns is still the type of marbling that I enjoy the most and find the most rewarding. Most of the papers I produce are for bookbinders or private presses, who use them as endpapers or covers for limited editions. Papers are also popular for use on lampshades and wallpaper, and for lining cupboards, shelves and boxes.

One of the joys of marbling is that it is easily transportable. After starting my business in Pay-hembury in Devon, I moved to Edinburgh, having become attached to Scotland during university days there. From there I made regular sojourns to various islands in the Hebrides for months at a time, taking my marbling tray with me and gathering the carrageen seaweed on the shore to make my size. There I met and married my husband, who is involved in rhino conservation, so years in Kenya, Botswana and Zimbabwe followed. Marbling continued, and all went well as long as the postal system was working. My customers have become accustomed to receiving parcels from far-flung places. We now spend summer months in the Outer Hebrides, which is an inspiring place to work from (the only drawback being that if you don’t get to the post office before 9.30am, the parcels will miss the boat).

I have now been producing marbled papers for forty years and still get a thrill when all is going well and when the drawing of the sheet from the tray is a pleasant surprise. I feel that I have been very lucky with my choice of occupation. It is not stressful and can be very therapeutic and mindful.

CHAPTER ONE

PAPER MARBLING STYLES

There are several different marbling methods that have been used by marbled paper artists over the centuries. They mainly vary in the type of size and paint used, and these variations have a big impact on the style and texture of the resulting designs. All marblers develop their own favourite ways of creating size and mixing colours in order to achieve their desired results.

An example of suminagashi marbling using ink and water.

Suminagashi