28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

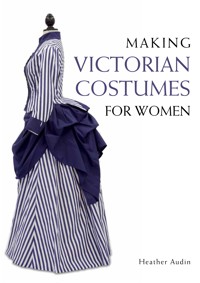

Starting with the early years of Victoria's reign, this essential book examines the developments and evolution of fashionable dress as it progressed throughout her six decades as queen. From the demure styles of the 1840s to the exaggerated sleeves of the 1890s, it explores the ever-changing Victorian silhouette, and gives patterns, instructions and advice so that the amateur dressmaker can create their own versions of these historic outfits. Other topics covered include: information on tools and equipment; a guide to transferring pattern pieces; a concise guide to the various layers of Victorian underwear; step-by-step instructions with colour photographs to help construct the patterns and advice on how to personalize the outfit. Illustrations of fashion plates, Victorian carte de visite photographs and original surviving garments provide visual inspiration and reference.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 261

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

MAKING

VICTORIAN

COSTUMES

FOR WOMEN

Heather Audin

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2015 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

© Heather Audin 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 052 2

Contents

Introduction

1 Exploring Victorian Costume

2 Tools and Equipment

3 Measuring and Pattern Cutting

4 Before Starting Your Project

5 The Importance of Foundation Wear

6 Modest Modes of Early Victorian Fashion

7 The Age of the Cage Crinoline

8 The Crinoline Changes Shape

9 The Soft Bustle Era

10 The Natural Form

11 The Second Bustle Era

12 The Dominance of the Sleeve and the Tailored Look

13 Completing the Look: Hairstyles and Accessories

Conclusion

Notes

Further Reading and Bibliography

Acknowledgements and Image Credits

Index

Introduction

This book is intended to provide a practical and useful guide to recreating authentic-looking Victorian women’s clothing. Spanning the six decades of Queen Victoria’s reign, it will look at the main characteristics that dominated the major fashion developments in this period. Through photographic images, fashion plates and pictures of authentic Victorian costume, the reader will be able to see how the fashionable silhouette was constantly evolving, placing emphasis on different parts of the outfit. The reader will then be able to use the pattern pieces and fabric suggestions to create their own garments, adding their own individuality and flair by adapting the colours, trimmings and styles according to their own style and purpose for creation.

Naturally, as with all books that cover a large time span, there are limitations as to what one publication can do. This book covers the big changes; the categories which are usually well known such as the crinoline to the bustle and finally the leg-of-mutton sleeve. Styles did not suddenly emerge into being, or suddenly, universally, stop being worn. Fashionable dress was constantly changing, with new trims, different colours, and variations on sleeves or bodice details for every season. The succession of these small changes then add up to more noticeable ones, which tend to give us the main style characteristics that we will cover in this book.

Fashion plate from Le Journal des Modes from the late 1870s, showing multiple fashionable frills and decoration on the excess fabric which previously sat higher over a pronounced bustle.

Who is this Book for?

First, I should perhaps explain my background. I have always been interested in history, historical costume and sewing. In my day job I am a museum curator and have been fortunate enough to work with several wonderful historic textiles collections, looking after them, researching and documenting them and interpreting them for exhibitions. In my own time I make replica historical costumes, sometimes commissioned by museums and galleries for educational activities, and sometimes for my own enjoyment. I always try to recreate them to look as authentic as possible, but, depending on their reasons for creation, other factors (such as durability, ease of fitting and budget) can sometimes take priority. These are factors which might also affect what you are making, and must be weighed up against each other in terms of importance. But more about that later.

This book is aimed at the amateur hobbyist and assumes some prior knowledge of dressmaking. Some of the outfits contain more components and are more complex than others. Those in the earlier decades have fewer pattern pieces and are more straightforward in their construction. Dresses from the later decades often use internal ties and tightly fitted bodice pieces that need a little more patience. However, I always find it is still fun to have a go, even if you initially think the standard of knowledge required is more than your current experience. You learn and adapt as you go, finding individual ways of working that suit you, and discovering different ways of doing things. And even if the finished result is not quite what you were intending, all experience is valuable and can be put towards your next costume venture.

It is also hoped that this book will be of some use to the more experienced practitioner. Those trained in historical dressmaking or theatre costume production will already have a vast and secure knowledge which will no doubt exceed my own, and will know different ways of working according to their professional environment and training. However, it may be that the illustrations and photographs are still a useful source to add to their existing library of information.

What You can Expect to See in this Book

The first part of this book aims to provide some general information, both historical and practical. An overview of the main changes in Victorian fashion will give the reader a bit of general knowledge, which will then be expanded in more detail at the start of each project section.

Information on how to use the patterns, what tools and equipment are required, and some things to think about before you start making any of the outfits, form the basis of a practical section which should make the projects that follow clear and user-friendly.

The main part of the book is divided into project chapters, which explore the different fashionable styles in more detail. Starting with the main stylistic features of that period, each chapter provides visual sources in the form of original photographic portraits, magazine fashion plates and some photographs of surviving Victorian garments. The aim of this is to show the main characteristics in these various forms, but also to show the great variety that you can take inspiration from. Use these to pick and choose which elements you like to help you customize your project and create authentic but personalized garments based around the patterns given. Remember, different styles and colours suit different people. Cassell’s Family Magazine gives us a good rule to think about when creating our own designs – ‘No woman ever dresses well unless she thoroughly understands what suits her individually, and no woman is badly dressed who has mastered that subtle knowledge’.

Victorian haberdashery.

Each project chapter contains a pattern for the main components of a dress for most of the major styles of the Victorian period: each is drawn in metric to a scale of one square to 2cm. This can then be scaled up and redrawn on dressmaker’s squared paper, and used to create your own pattern to make the dress. Step-by-step instructions with accompanying photographs describe the construction process, and images of my version of the finished outfit give you an idea of what the costume looks like when completed. Bear in mind that every version will be different due to different fabrics, colours and makers. Variation is good! All dresses in historical collections represent great variety and individuality.

Finally, a chapter on completing the look provides some information and images on other factors that can help to give an authentic flavour, such as hairstyles, jewellery and accessories. This is by no means extensive, and I encourage you to do your own research to find out what would authentically complement your outfit, but this will give you a basic start. A concluding note on fashion beyond the Victorian period helps you to see how things continued to change and develop into the twentieth century.

Chapter 1

Exploring Victorian Costume

1

To start our exploration of women’s clothing in the Victorian period, this chapter will provide a brief overview of the main style changes that will be explored in greater depth throughout the subsequent projects in this book. One style gradually evolved into another, each laying the foundations for the next major development which became a characteristic and dominant style. We will then take a look at some of the visual sources you can use to explore the developments in Victorian costume, which can provide inspiration for your own creations based on the patterns given here.

Original printed cotton dress c.1850s, with a tightly gathered skirt and neat gathers at the waistline of the bodice.

Fashions at the start of the Victorian period are often described as modest and demure. The high waistline of the Regency period, which characterized female dress for several decades by providing a draping, classical line, gradually began to drop back down nearer to natural waist levels in the late 1820s. The simplicity of the Regency dress gave way to increasing levels of decoration, and the sleeves began to bloom out of all proportion, so much so that padded sleeve inserts were required to support them. The exaggeration of the 1830s had subsided by the time Queen Victoria came to the throne, and what followed was a period of more sombre and plain dress, noted for its lack of decorative ornament. Sleeves were tight and set low into the shoulder, restricting arm movement. Voluminous skirts, tightly gathered into the natural waistline, often formed a point at the centre front and were supported by numerous cumbersome petticoats, adding more bulk, weight and restriction to movement. Large shawls enveloped the figure and faces were hidden by round bonnets.

As the mid-nineteenth century progressed, fashions began to break away from the sobriety of the 1840s as decorative frills and flounces added emphasis to the growing circumference of the skirts, which now needed a serious support structure to maintain the fashionable shape. Advancements in technology allowed the invention of the cage crinoline, a frame petticoat made from sprung steel hoops which provided volume without the weight, and for many this was a welcome relief from the multiple layers of heavy, padded petticoats previously required. Light fabrics in tiered flounces were popular and created the typical chocolate-box vision of Victorian fashion. Sleeves echoed the skirts and also expanded into deep frills and cuffs, with dainty undersleeves filling in the gap between sleeve and wrist. The large volume of the skirt was in some ways beneficial: by its sheer size it created an impressive illusion of a small, delicate waist, which reduced the need for corset tight lacing.

In other ways, however, the crinoline did pose a health risk, or at the very least some potential for social embarrassment. The lightness of the cage frame meant it was prone to being caught in the wind and blowing up, revealing more than was considered polite. It was also reported to be the cause of many accidents, getting trapped in carriage doors or sweeping a little too close to the fire for safety. By the mid-1860s, the shape of the crinoline began to change. Instead of the evenly rounded dome shape the front became more flattened whilst the rear was extended. Thus, in plan, the crinoline took on an ellipse shape and the silhouette was increasingly asymmetrical. For the first time, the skirts were made from shaped, gored panels that narrowed at the waist instead of wide, rectangular lengths of cloth tightly gathered into the waistline. Peplums were essential to enhance the silhouette, and were worn on belts around the waist or on long basques extended from the bodice. Loose mantles provided an overall triangular shape to the fashionable line.

As the cage crinoline fell out of favour, the long lengths of skirts trailing behind were looped up by internal rings and tapes, creating a soft bustle at the back of the dress. Still requiring some support, underwear adapted to provide the crinolette, a kind of half-petticoat whose steel curves at the back supported this growing bustle shape. The first of two bustle eras, this style was characterized for sitting very high, protruding out almost from the small of the back. The increased volume in the skirts was echoed in the fashionable hairstyles, which featured a large amount of false hair in the form of plaits, chignons and curls that sat high on the head. This characteristic use of false hair is useful in identifying the dates of photographs from this period, and helps to distinguish them from the bustle dresses that came in the second bustle phase of the 1880s.

By the late 1870s, the bustle began to fall, until the concentration of swags, gathers and decoration rested around knee level at the back of the skirt. The rest of the skirts flared out into a decorative train which gracefully swept the ground behind the wearer, though rather unhygienically, as it also swept up the dust and dirt on the ground. The rest of the dress became tight and slim, hugging the body and hips in heavy boned and restricted princess-line dresses and cuirass bodices. Long, heavily boned corsets were needed to create the right hourglass proportions of this ‘natural form’ era, and this was possibly the most restrictive style of the whole Victorian period. By the 1880s, the train had also disappeared, creating an overall slim silhouette with relatively plain tops that contrasted with multiple rows of skirt pleats and decoration.

After a couple of years, the bustle, or ‘dress improver’, once again came back in vogue, and heralded the start of the second bustle era. In distinct contrast to its previous incarnation, this version was more angular with less drapery and frills than characterized its forerunner. It jutted out sharply behind, and was worn several inches lower. The tailored look influenced the overall style, as rows of buttons and mock waistcoat fronts in contrasting materials were popular bodice styles. By 1888, the dress improver was abandoned in Paris, and by 1890, in Britain.

As one element declined, so another grew, and the fashions of the last decade of the Victorian period saw the rapid growth of the sleeve, inspired by the fashions of the 1830s. Starting as a small peak in the late 1880s, the top circumference of the sleeve grew so much that its immense width created enormous puffed leg-of-mutton sleeves, which gave a very wide appearance to the top of the female form. In attempting to balance out the shoulder width, skirts, which had decreased in volume, once again began to flare out at the hemline. With sleeves of such large proportions, coats were impossible, so shoulder capes became fashionable as outerwear. Whilst these ensured that the sleeves were crushed, they served to further emphasize the width of the shoulders. The sleeve width reached its peak in 1895, before starting to deflate to a more sensible size at the close of the decade, the century and Queen Victoria’s reign.

The new century started a new era which would see even more dramatic changes in fashion. Edwardian opulence, characterized by frothy frills of lace and S-bend corseted female figures would then experience the slimmer silhouette of the 1910s with peplum skirts and fashionable blouses. Into the 1920s, there was a dramatic change from the curvy and feminine form emphasized throughout Victorian and Edwardian fashion to a boyish and straight idealized form, with dresses that were slim, skimpy and short.

A Note about Sources

Luckily, the Victorian period gives us a great number of visual and written sources for reference that are useful in recreating fashions from this age. The proliferation of women’s magazines containing illustrations and fashion descriptions, as well the rise in popularity of photography, give us valuable information on which to base our re-creations. There are also a great number of original garments surviving from the Victorian period, which can be seen in museum collections or viewed in books and online. These show the wide variety of styles, tastes and fabrics which were worn by women at this time.

Fashion Plates and Magazines

Fig. 1.2 Fashion plate from The World of Fashion, 1852, showing multiple-flounced skirts popular during the 1850s.

Fig. 1.3 Fashion plate from The Young Englishwoman’s Magazine, 1865, showing the development of the crinoline to an elliptical shape.

Fig. 1.4 Fashion plate from Journal de Demoiselles, c. 1870s, showing the style of the first bustle era.

Fig. 1.5 Fashion plate from La Mode Illustrée, 1878, showing a slim-line silhouette between the two bustle eras.

Fig. 1.6 Illustration from The Girl’s Own Paper, 1883, demonstrating the look of the second bustle phase and the smart tailored tweed used in the central figure.

Fig. 1.7 Fashion plate from Le Journal des Modes, showing large sleeves and wide collars, both characteristic of the last decade of the Victorian period.

Fig. 1.8 Frontispiece from The World of Fashion, A Journal of the Courts of London and Paris: Fashion, Polite Literature and Beaux Arts.

Fig. 1.9 Fashion plate from The Ladies’ Treasury, September 1876: these idealized illustrations would have been used to inform women of the latest styles, elements of which could then be made up into a dress.

Fashion plates were hand-coloured images that were available in women’s magazines and demonstrated to the reader the latest styles and modes. One of the earliest British titles, started in 1824, was titled The World of Fashion, whose monthly magazine contained four hand-coloured plates with the main focus of the text being fashion advice. Other popular titles, such as The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine and The Queen, contained fashion advice as well as other household tips, serialized stories and letters pages. Magazines with coloured plates could be expensive, but a range of other publications were more readily available by providing black and white illustrations instead. Many of these gave the opportunity to buy the patterns for the dresses described by sending away for them by post, at extra cost.1

Doris Langley Moore describes fashion plates as ‘aspirational’ rather than a realistic representation of what women wore. They are like the perfectly airbrushed models in twenty-first-century magazines – always pristine, beautiful and showing off a perfect figure. She strongly asserts that very few women in the Victorian period actually looked like a fashion plate. As with all types of illustrations and magazines, there was an element of uniformity and artistic licence, and this could not be realistically achieved by all women. It is also interesting to note that they would present more extremes of fashion or exaggerations of particular features than is often found in surviving dress. Waistlines are more pointed, sleeves are more exaggerated, crinolines are shown of unmanageable proportions and necklines sometimes lower than what was actually worn by the majority of women. In some ways they can be seen as the least useful of the sources mentioned here in terms of true authenticity of what was actually being worn.

However, they are still very important, as these are images which women were looking at and aspiring to at the time. Women could take the aspects they liked the best, decide what elements they liked and what might suit their individual requirements, and use them – or instruct their dressmakers to make them up into more practical and personably suitable garments for the individual concerned. Therefore, for the purposes of your own Victorian dress recreations, the fashion plates included in this book can be used in exactly the same way – as inspirations for your own individual designs.

And, despite the apparent disparity between the ideal and the actual, the descriptions provided in the magazines are very useful in knowing what was considered fashionable that season, and can be used to create authentic-looking outfits. They might give you a good idea for some trimmings or let you see which colour combinations were most favoured. Many will state the fabrics used, which means you can try to match your outfits to those being described, and it gives you a good idea as to what was both fashionable and available for Victorian dressmakers, remembering of course that these are illustrations and descriptions for the fashionable lady – those of lower means would have to use cheaper and less desirable fabrics.

If you are lucky enough to find a magazine relatively intact, there may also be the odd pattern that you can draft and reconstruct, giving you a very authentic piece. In many magazines it states that the patterns are to be sent away for, but some children’s patterns or odd outfits such as a bodice or mantle may have patterns which feature in the main text of the magazine. They do require careful reading, but with measurements and large paper you can get a good idea of the pattern piece shapes, and trying to make them up can be really fun.

Photographic Sources

Fig. 1.10 Original photographs, such as this one from the 1880s, help to give us a realistic understanding of what women actually wore and how it fitted the body.

Fig. 1.11 Photographic portraits required a special visit to the photographer’s studio, and often have elements of stage setting, such as the painted backdrop window and bookshelves seen here.

Photographic portraits provide a more reliable source for seeing what people actually wore, and how the fashions depicted in magazines translated into real dresses on real people – of all different proportions. They are an enormous resource that gives you a realistic view of not only the fashionable dress styles, but changes in accessories, hairstyles and the general look which all develop and change throughout the decades. They give us an idea of how the fabric sits on the body and how the garments fitted according to the creases, folds and wrinkles, which help with reconstructing these garments.

The earliest photographic portraits available to us are from the 1840s, although they become much more widespread from the 1850s–60s. Luckily, this gives us photographic access to fashion in almost the whole of the Victorian period. Photography was experimented with in the early decades of the nineteenth century. The first types of photographs, daguerreotypes, were images fixed to silver-plated pieces of copper in the late 1830s. Steady developments in technology, camera lenses and developing processes during the 1840s allowed photographs to be produced on paper, and the whole art was employed in recording landscapes, buildings and, of course, people.2Carte de visite portraits became fashionable in the early 1850s, meeting the demand for portraiture from a burgeoning middle class that could not be satisfied by the slower and more expensive alternative of painted portraits. The 1860s saw the start of a craze for collecting carte de visite portraits – a fashionable trend led by Queen Victoria herself – which continued throughout the rest of the Victorian period.

Initially, exposure times were very long, which required the sitter to keep still or risk a blurred picture. But technology developed quite quickly, and the need declined for clamps and stands to keep the sitters in a rigid, still position. Nevertheless, the desire not to blur your portrait could explain part of the reason for the rather formal-looking nature of Victorian photographs.

Painted portraits are still a valuable resource (certainly before the advent of photography) but were often the preserve of the upper classes, and sometimes present a particular or desired version of the person being portrayed. Their fashion may not be typical as they often intend to show a certain message or emphasize a certain characteristic. Sometimes, the sitter is painted in fancy dress or represented as a historical or mythical figure, which does not necessarily help us with an accurate idea of costume.

It is interesting to note that photographic sources will also have a sense of bias and element of stage setting. In an age when a specific trip to a photographer’s studio was a luxury not often repeated, no doubt you would want to wear your best outfit and present the best image of yourself. The clothing worn is therefore likely to have been made in the most fashionable design and fabrics that person could buy, make or afford, and this would vary according to the individual.

Although the carte de visite and cabinet portraits portrayed the middle classes, photography of the working class and the poor in large cities can be found in the work of social investigators of the late Victorian period, who were recording poverty and overcrowding in industrial city slums. Whilst the purposes of these images are to record the living conditions of its poorest inhabitants, they are also useful in that one can see the simplified and more practical fashions worn by the working classes.

Original Garments

Fig. 1.12 Original garments are a useful resource for examining internal seams, stitching and how clothing was constructed.

We are also fortunate that many original garments from the Victorian period survive. Museum collections hold a wealth of information and a whole range of unique objects preserved from the past. Care must be taken with some items that survive in museum collections. Many garments have survived because they were made for special occasions marking life events (such as wedding, christening and mourning outfits) or were favourite or best dresses. These items are therefore not necessarily representative of the typical, everyday dresses which may have been more practical but which were worn to destruction. Museum collections also rarely represent costume from the working classes, or uniforms and working wear. Again, these are often not thought of as worth saving, or they were used, reused, mended and passed down to younger family members, prolonging the life of the garment as long as possible. There is less sentimentality attached to this kind of clothing, so whilst a best dress might be saved and treasured, everyday working outfits are not.

The great asset of examining original garments is that they show real dresses and how they were actually made, and what fabrics and methods of construction were used. In studying how these examples were made you can get a good feeling for the maker. In many cases these items were made at home, and it is reassuring to find quite large stitching, unfinished edges and errors hidden by trimming or bows. It is interesting to note that decoration is often only lightly sewn on with large stitches. This could then be easily removed and swapped for a different, more up-to-date trimming if the fashions changed into the next season. No one saw the inside, and it would not have to stand up to the rigours of washing, as it was the underwear rather than outerwear which was more frequently laundered. Depending on the dress and the decade, garments can range from remarkably simple to incredibly complicated, with all manner of variation in between.

Whilst we are lucky to have these items saved in public collections, it is important to realize that many museums now are not necessarily able to facilitate access to private study visits, and there are restrictions on access to fragile historic collections. As a researcher with an interest in costume history you will not automatically be able to handle and measure museum examples of costume unless you are researching a specific project. While this might initially seem harsh, it must be remembered that many original garments survive in a fragile state, and museums have a duty of care to prevent over-handling of objects they are trying to preserve. There are also increasing restrictions on staffing levels to provide access to collections, as curators and collections staff are stretched between multiple collections and tasks.

Despite what you might initially think, museums are dedicated to providing access, and in our digital age we have a great deal of accessibility to museum collections all across the country, and in fact the world, through the power of online catalogues. Furnished with object descriptions and photographs, you can virtually explore costume from museum collections. The internet in general is also very useful for image searches, providing a wealth of information and design inspiration.

Whilst virtual access is good, do not underestimate the power of seeing the real thing. Even if you are unable to book a personal study session, visiting a museum costume display is well worthwhile and gives you a different feel for the items from what can be gathered from a flat book or web page. Seeing how fabrics drape and fit on a three-dimensional shape is informative, and seeing them in the settings and context interpreted by a museum can greatly enhance your appreciation of the costume.

Costume History Books

Fig. 1. 13 The inside seams of original Victorian clothing are just as interesting as the exterior. (Image © Hands on History: Hull Museums)

There are a large number of titles available on costume history, and the Victorian period is well covered by historians who have built up a large body of knowledge and expertise. Some provide purely historical information, whilst others combine that information with patterns and images of original garments. All of these books are useful for your library, and help to get different perspectives on Victorian clothing. You can find a list of useful books in the Further Reading section at the back of this book, though there are doubtless many more out there which would also be useful to you.

Chapter 2

Tools and Equipment

2

There are lots of tools and equipment available to the modern seamstress. Some items are essential, whilst others are a useful and desirable addition to make things a little quicker and easier, but the task can still be done without them. Those who already do some sewing will probably already have a lot of what is required. It is also true that everyone works slightly differently, and you might find that you adapt to certain working practices or prefer to use different methods according to your own personal way of working.

As with many tools, good-quality items can be expensive, but it can be worth investing in some key items which make your work more accurate or save you time. Cheaper tools can also be false economy, and may break quickly or produce inferior results, which is counterproductive if you invest a lot of time and effort in a project.

Some tools are essential, others make the job easier. A sewing machine (albeit a more up to date one!) makes the job much quicker, and was adopted as an essential tool with wide enthusiasm in the Victorian period.

Essential Tools

Here are the essentials – the tools you would struggle without:

Fig. 2.2 Sample of some of the tools which are useful in the construction of replica Victorian clothing.

Tape measure: This is essential throughout the whole making process. You use it to take the measurements of the person you are creating the outfit for, and for measuring during construction. The old saying is definitely worth remembering – measure twice, cut once!

Fabric tape measures are better than metal DIY ones as they are flexible to fit around the three-dimensional shape of a body. Most tape measures have metric measurements on one side and imperial measurements on the other, so you can use either side depending on your preference. I tend to use a mixture of both depending on what side I happened to have used, but it is probably best to be consistent for more accurate measuring.

Tape measures can stretch slightly over time, so if yours is looking a bit misshapen then it might be time for a new one.

Scissors: