Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

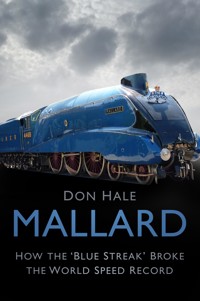

Just over eighty years ago on the East Coast main line, the streamlined A4 Pacific locomotive Mallard reached a top speed of 126mph – a world record for steam locomotives that still stands. Since then, millions have seen this famous locomotive, resplendent in her blue livery, on display at the National Railway Museum in York. Here, Don Hale tells the full story of how the record was broken: from the nineteenth-century London–Scotland speed race and, surprisingly, traces Mallard's futuristic design back to the Bugatti car and the influence of Germany's nascent Third Reich, which propelled the train into an instrument of national prestige. He also celebrates Mallard's designer, Sir Nigel Gresley, one of Britain's most gifted engineers. Mallard is a wonderful tribute to one of British technology's finest hours.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 294

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Frontispiece: LNER class A4 4468 Mallard’s nameplate. (Don Hale)

Front cover: Mallard original image by PTG Dudva via WikimediaCommons, CC S.A. 3.0.Rear cover: calflier001 via WikimediaCommons, CC S.A 2.0.

First published in 2005 by Aurum Press Ltd.

This edition 2019

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Don Hale, 2005, 2018, 2019

The right of Don Hale to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9291 6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Turkey by Imak

CONTENTS

Preface

About the Author

1 The Races to the North

2 Nigel Gresley and the Great Northern

3 The London and North Eastern Railway

4 The Flying Scotsman

5 Developments across the Channel

6 Streamlined Efficiency

7 Faster and Faster

8 The Germans Increase the Pressure

9 The LMS Draws Ahead

10 Mallard Spreads Her Wings

11 The Day of Reckoning

12 After the Record

13 Mallard’s Great Gathering

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

PREFACE

Imagine if you will, travelling back in time to witness the final flickering of a golden age. You wouldn’t need to go as far as you think, in years or in distance. Say 1960, or perhaps a year or so later; the location, the largely flat countryside of west Lincolnshire a few miles south of Grantham. It was a time when summers were endless and blazing hot. In the evening, when the heat of the day starts to ebb away, imagine taking a walk through some fields of ripening wheat to a nearby railway cutting. Picture leaning against a fence for a while, just relaxing, enjoying the wonderful scene. But for boys of all ages, as a book once said, this place is far more significant than a mere beauty spot: it is a place where history was made. A procession of modern diesel trains rumbles past – their locomotives are heavy, cumbersome and no more powerful than the steam locomotives they are rapidly replacing. They may be one of the wonders of the age, but aesthetically they are just ‘boxes on wheels’, all the wonder of what makes them work hidden inside.

Then, the wind carries the faint trace of a siren – it could be mistaken for the wail of an air raid, but those haven’t sounded for fifteen years. No, this is something much more exciting than an air raid. Minutes later, the faint sounds of a steam engine make their presence known. Still some miles away, it’s working hard and approaching fast. There’s no towering column of smoke, meaning whatever is coming is really moving, and then it’s there. With the clatter of the coaches beating a tattoo on the rails, the engine rounds the bend and attacks the hill. But this is no ordinary engine – the shape gives the game away. She’s no longer in pristine condition and streaks of grime are visible on her smooth aerodynamic casing. But, like a fading actress, she still has her admirers and can still give a winning performance. She was built for speed, and even at 70mph lopes gracefully, seemingly secure in the knowledge she could go much faster if she really wanted to. The engine may be going fast, but it’s almost silent, the loudest noise that of wheel on track and of the coaches behind. As she gets almost level, the driver blows the whistle again. Another wailing scream that starts in defiance but gradually fades into a low moan of resigned acceptance, and with a clatter of carriages rattling away behind, she’s gone, racing on the way north.

If this is not quite the final curtain of a golden age, it’s certainly close to the last act of an era that saw breathtaking courage, sublime skill and artistry of the highest order produce one of the finest feats of engineering ever: a superbly streamlined, exquisite masterpiece of a steam locomotive called Mallard.

My own interest in railways began more than sixty years ago, during a now-forgotten era, when my brother and I would travel the country as rail enthusiasts or trainspotters. Nowadays, we would be called ‘anoraks’ and probably banished to the far end of some dilapidated platform at a main-line terminus. I had little interest in diesels or electric trains then, simply preferring the power and majesty of steam. The A4 Pacific class are still my personal favourites – to see an A4 flat-out in full cry was certainly a sight to behold: they hurtled through the Scottish Lowlands during family holidays and, if I close my eyes, I can still hear their shrill whistles. It’s the kind of scene I remember vividly more than six decades on, and that inspired me to write this book.

Don Hale

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Investigative journalist and author Don Hale became nationally famous for his tireless – and ultimately successful – campaign, while editor of the Matlock Mercury newspaper, to help clear the name of Stephen Downing, imprisoned for twenty-seven years for the murder of a Derbyshire woman.

Author Don Hale on the footplate of Sir Nigel Gresley at Grosmont on the North Yorkshire Moors Railway during filming for a Channel 4 documentary. (Don Hale)

It earned him the OBE and he was acknowledged to have righted a major miscarriage of justice. He went on to have equal success with three other miscarriage cases, and he has campaigned on other several human rights issues, even helping to change both European and British law. He has written several bestselling books.

Don is also a former professional footballer and still likes to keep fit by running most days. He has won several veteran titles and encourages many others to stay healthy.

A former trainspotter and railway photographer, Don remains passionate about the story of Mallard and the incredible works of Sir Nigel Gresley, one of the country’s top mechanical and railway engineers. He is now semi-retired and lives in north Wales.

1

THE RACES TO THE NORTH

Mention the term ‘arms race’ and you instinctively think in terms of military build-ups in the twentieth century: the Dreadnoughts of 1904–14, the Spitfires and Messerschmitt 109s of the 1930s, and the space race of the 1960s. All were politically motivated, and all had consequences that would change the way we live. But arms races aren’t always about weapons. In the 1930s, an equally exciting competition between Britain and Germany was taking place on the railways. Throughout that decade, records would be made and broken, culminating in a high-speed run in 1938 by the famous locomotive Mallard that has never been bettered since by steam traction.

It was a hugely significant event that went beyond the breaking of a speed record: at a point when Nazi Germany seemed to be having everything its own way, Britain’s triumph proved that ingenuity and determination could beat the Nazi regime. At a time when British morale was faltering, this success provided a much-needed fillip. Mallard is significant in other ways, too: her creation marked the culmination of more than a hundred years of steady development for the steam locomotive, and her record-breaking sprint from Grantham to Peterborough set the high-water mark for railways everywhere. Despite all the technological breakthroughs that have happened since, Mallard still represents for many the zenith of the railway’s golden age, before war followed by nationalisation and then re-privatisation saw its painful decline. How Mallard’s triumph was achieved, and why, forms the subject of this book.

The desire to go faster, higher, farther seems to be an intrinsic part of human nature, which is why, in 1804, a Cornish engineer called Richard Trevithick invented the steam locomotive. The desire to make money is another intrinsic desire, which is also why colliery owners in north-east England started to use steam locomotives, as they could haul more than horses.

At the famous Rainhill Trials in 1829, Robert Stephenson’s Rocket reached a frightening 29mph, and less than twenty years later the unprecedented speed of 60mph was the norm on some railways. These were the fastest machines ever invented at that time – the equivalent of a rocket today – and any speed advantage was immediately seized on by the companies involved to promote their routes and win new business.

For the railways, going faster was a deadly serious competition, with the various railway works around the country pushing materials and manufacturing techniques to their limit. At first, the Great Western Railway, with its flat route from London to Bristol and wider tracks than anyone else, held the advantage. By the 1860s, however, other companies had caught up. These were heady times, but because each company operated on generally different routes, it was difficult to compare performances on a like-for-like basis. This didn’t deter two alliances from competing with each other in a series of races that lasted years (with occasional interruptions) and effectively set the pattern for the story of Mallard.

The rivalry lay between the two routes to Scotland – the West Coast Main Line from London Euston through Rugby, Stafford, Preston and Carlisle, and the East Coast route, which ran from London King’s Cross through Peterborough, Doncaster, York, Darlington and Newcastle to Edinburgh; both still run today. The first railway route from London to Glasgow and Edinburgh, up the West Coast of England, was completed in 1847 and operated jointly by the London & North Western Railway Company and the Caledonian Railway Company. The rival line, the slightly shorter East Coast route, opened some four years later following an alliance between the Great Northern, North Eastern and North British railway companies. ‘Speed’ soon became the buzzword of the period. Within ten years of opening the East Coast line, its operators were proudly boasting that they offered a much faster schedule than their rivals. Unlike today’s heated competition between budget airlines, in which the key factor is who offers the lowest fares, price was no issue: speed was all.

At this time the railway operators had a rather unfortunate image. They were the butt of newspaper jokes and often mocked by caricaturists of the day. The public expected that trains would be cold, dirty, smelly, slow and downright uncomfortable – and they were usually right. Imagine ten or more hours in a third-class compartment, with oil lighting, no heating and wooden seats, sometimes upholstered but still painful for long periods – not a pleasant experience. But with the only alternative being several days in a horse-drawn carriage, there was little choice for anyone who wanted to go to Scotland, or anywhere else for that matter.

In many ways, the railways reflected social and economic change – paradoxically, change that the railways themselves had engineered. Massive construction challenges and manufacturing problems had been overcome, and the railways provided a means to move produce rapidly. As more lines opened, people began to commute into work. For the railways, gaining the hearts and minds of this expanding clientele was vital.

Backed by their new, ‘racing style’ image, the directors of many railway companies determined to lose their old-fashioned tag and reinvent themselves. First, they began to encourage fast services from London northwards: to the growing industrial centres of Sheffield, Manchester and Birmingham and, of course, across the border to Scotland. However, at this early stage, they also promoted quality and convenience rather than pure speed.

Then, between 1872 and 1876, the Midland Railway Company decided to build its own line from Settle to Carlisle, which enabled it to bypass the existing LNWR route from Crewe to Carlisle and thus set up its own service to Scotland. Even more importantly, it confirmed plans to admit third-class passengers to all of its services for the first time in its history. The news came as a bombshell to many of the other class-ridden railway operators, especially to the rather highbrow East and West Coast firms. Then, a few weeks later, they received a second shock: the Midland Railway said it was also going to scrap the second-class service and upgrade third. It could now justifiably boast its trains were more luxurious than the competition.

At this stage, the East Coast service in particular had been content with competing for the quality of its passengers rather than the quantity, but this new series of statements from their Midland rivals meant that they now faced serious competition and risked losing a large part of their market. In response the Scotsman service finally admitted third-class passengers and announced a new running time of nine hours.

Disturbed by the threat of further competition from a new rival and by the constant and infuriating boasts of ‘superior speed and revised schedules’ from the East Coast line, in May 1887 the West Coast management team unexpectedly rebelled. They announced that they would not only match their competitors but beat them, with a new operating schedule of just nine hours from London to Edinburgh – exactly the same time as the rival train the Scotsman, with a broad hint they could, and probably would, improve on that.

This bold move led to renewed boasts from all sides, which not only attracted interest but also rallied public support. The foreign press soon picked up the story and for many months the directors of several continental railway companies kept a watching brief on developments. Any news, no matter how trivial, was eagerly gobbled up and reported by the volatile and jingoistic British press. In those years the newly united Germany, fresh from its success in the Franco-Prussian war, was building up its military in a bid to acquire an Empire along the same lines as Britain’s. National superiority was vital.

By 1 August 1887, less than four months after the West Coast first launched their high-speed programme, the East and West Coast outfits began running head-to-head from London to Scotland – eventually revising an already punishing schedule to just eight hours. At first the two companies seemed fairly well matched, but all this changed when the East Coast Company deliberately tried to take the lead. Determined not to lose out, they vowed to reduce the Scotsman’s running time to just seven hours and forty-five minutes, and ran a special test train to prove the point. This recorded an outstanding performance, racing from London to Edinburgh in just seven hours and twenty-seven minutes, twenty minutes under the advertised schedule – even allowing for a near half-hour stop at York for lunch and an unexpected delay caused by a swing bridge at Selby.

The East Coast management were elated by their success but realised that it came at a cost. Running trains at such high speeds was becoming increasingly expensive in terms of maintenance, and there were safety issues too; a derailment or, even worse, a crash would be a disaster for all concerned. The day after the record-breaking run, the directors of both alliances met and reluctantly agreed to a compromise, a more conservative schedule of just under eight hours and thirty minutes. To the great disappointment of the public and doubtless some of the drivers (but perhaps not the hard-pressed firemen) the racing stopped – at least for a few years.

Meanwhile, British engineering continued to expand the frontiers of possibility with the opening of the Tay Bridge in 1887 and the Forth Bridge in 1890. These magnificent structures reduced the East Coast journey from London to Aberdeen to 523.5 miles, against the West Coast distance of 540 miles, and overall journey time to twelve hours and twenty minutes from King’s Cross. There were unprecedented demands from the public for new trials; the press continued to focus on the issue and observers from across the world waited eagerly to see what would happen next.

They were not disappointed. In June 1895, determined not to be beaten again, the West Coast alliance entered the fray, recording a new world-record time of eleven hours and forty-five minutes from Euston to Aberdeen. Its rivals were not slow to respond, and for a thrilling seventeen days in July and August every night became a race to the finish, with timetables continually updated until the drivers of both services were told to cast schedules aside to make the best time they could.

On each of those nights, two express trains left London’s King’s Cross and Euston stations at 8 p.m., one on each route and both bound for Aberdeen. For the final 38 miles of the journey, from Kinnaber Junction, near Montrose, to Aberdeen, the East Coast train had to use West Coast tracks. Whoever reached Kinnaber Junction first would win the race, as strict intervals were enforced between trains running on the same track. The story goes that on one run, the trains were neck and neck and within sight of each other as they steamed furiously towards Kinnaber Junction. The signalman, who worked for the Caledonian Railway, had to decide which train to let onto the section first. In a sporting gesture, he gave the ‘road’ to the East Coast train – but it was as close as a race could be. Still, it was a little difficult to decide who had actually won, so the companies agreed to a change of tactics and switched back again to competing over running times instead of head-to-head parallel running.

On 20 August 1895 the East Coast express crew really excelled themselves. The train arrived at Edinburgh Waverley in just six hours nineteen minutes, then continued onward to Aberdeen in a superb combined time of eight hours forty minutes from London. This achievement claimed another world record and the Aberdeen through time remained on the books for eighty years, only beaten by the introduction of 100mph-plus diesel trains travelling the same route. The timings belie the sheer difficulty of running fast with steam locomotives. During the Aberdeen races, vital stops were needed on the East Coast route, and locomotives were changed at Grantham, York and Newcastle to avoid running out of fuel. Despite this, the train still managed to claim another record, achieving an average speed of more than 60mph for the entire journey – including the difficult gradient from Edinburgh to Aberdeen with a 100-ton load.

The next evening, the London & North Western and Caledonian Railway, determined to claim their share of glory, attacked the same target via their own West Coast route. They, too, had to make engine changes, this time at Crewe, Carlisle and Perth, and they also had to negotiate severe climbs at Shap Summit in the Lake District (915ft) and at Beattock (1,015ft), with three coaches in a 70-ton load. Although they did not quite overtake the running time of their rivals, they recorded another magnificent record, achieving a superb time of just eight hours forty-two minutes from London, for a journey that was some 17 miles longer, and a higher average speed of 63.3mph. These were remarkable achievements that pushed the technology of the day to its limits. They also set in stone the rivalry between East and West Coast routes that still exists to this day.

By the following year, many other national railway operators were also competing hard on speed. It suddenly seemed to be the craze of the nation: fast expresses now departed several times a day from the opposition London stations to Manchester, usually arriving within five minutes of each other. Press statements claimed racing trains rarely stopped for anything – including stations – and staff were instructed to give them priority. Timetables were discarded and drivers adopted a ‘gung-ho’ spirit, determined to be the first to reach Scotland, at almost any cost. Drivers and train crews certainly needed all their experience on the difficult northern routes, yet some began to take chances, realising that valuable minutes could be won or lost by successfully negotiating major obstacles at crossover points and junctions, or on sharp track curves. Some unscrupulous railway directors even reduced the number of coaches hauled, just to maintain top speed and give their trains a sporting chance. Despite other exciting runs on other cross-country services, it was the Scottish races that remained firmly in the public spotlight. The public remained curious, eager to know every minute detail about the contestants. Press coverage became intense – in one story, it was claimed that the races had encouraged gambling.

Inevitably, other main-line services, including freight, were affected. It was hard to run a reliable freight or local passenger service when the line ahead might be shut down unpredictably to allow the Scotsman through. Locomotives at the time were not equipped with speedometers (which were not standard on all railways until the late 1940s), so the authorities, concerned for public safety, insisted on the installation of track markers and mileage posts at quarter-mile distances. Even so, the line between calculated risk and outright danger was increasingly being crossed, especially at major junctions. The issue was of such concern that it was even debated in parliament. Fortunately, there were few mishaps or breakdowns during the speed runs. But in August 1896, a southbound express was derailed at Preston when it exceeded the speed limit entering the station. The two engines came to rest against a bridge wall with the coaches scattered across the tracks. Fortunately, there were only sixteen passengers on board, but one was killed.

The races were not an unmixed blessing even for the companies who initiated them. Many trains were double-headed and used numerous locomotives en route to haul coaches at speed. Maintenance costs soared, but despite keen public interest, passenger numbers fell disappointingly. Consequently, the directors of both companies agreed that in future they would concentrate on improving their services.

Other railway operators were still interested in breaking records. The Great Western Railway and London & South Western Railway began to stage their own spectacular competitions. In 1904 the GWR threw down a spectacular gauntlet, with a run from Plymouth to London that still ranks as one of the most daring railway operations ever. On 9 May that year, one of its new City-class locomotives, No. 3440 City of Truro, became the fastest train on British rails, with a timer on the train recording a top speed of 102.3mph. This figure has been disputed since and never officially recognised, but the balance of evidence suggests that whatever the top speed actually was, it was certainly around the magic hundred-mark.

After this, to the disappointment of many, most companies thought the records could wait. Railway technology was at its limit: to achieve faster speeds locomotives would have to become radically more powerful, with longer range. Even as the West and East Coast railways were busy racing, designers across the world were scratching their heads trying to work out how to provide a new generation of rolling stock to haul the heavy loads now being demanded, and luxurious carriages to attract new business. The emphasis quickly changed from speed to increased capacity and passenger comfort. Engineers concentrated on building more powerful locomotives and new rolling stock to carry heavier loads for greater profits.

The speed trials might be over, but their effects were long lasting. They had not only accelerated journey times but also provided a valuable impetus for the development of new locomotives and rolling stock. The achievements on the London–Scotland routes and elsewhere helped shape the future of the industry, and the investment poured into the railway network by competitive bosses provided skilled training and regular work for employees across the country.

The results also ensured Britain continued to rule the tracks, holding more than a dozen early, fully authenticated steam records. It was many years before overseas nations were able to mount any serious challenge, and in the meantime the British rail industry had not only gained acres of publicity at home but also attracted worldwide attention and admiration. Those eagerly awaiting the next races to the north would have to be patient. It would be another forty years before the successor companies on the two main lines succumbed once again to the allure of speed.

2

NIGEL GRESLEY AND THE GREAT NORTHERN

Around the time of the 1895 races to the north, Nigel Gresley, a young apprentice with the London & North Western Railway (LNWR), was employed at Crewe, Cheshire. While he must have watched the races with interest, he could not have known that some forty years later he would force the statisticians to rewrite their record books. For an observer of the 1890s, Gresley’s creations would have seemed beyond belief.

Born in Edinburgh on 19 June 1876, Gresley was the fourth son of the Reverend Nigel Gresley. He spent his early childhood years at the family home in Netherseale, near Swadlincote in Derbyshire, a comfortable existence with several live-in servants. Although Gresley came from a privileged background, he probably had the railway in his blood from birth: he was almost born on a train when his mother, Joanna, was forced to visit the Scottish capital whilst heavily pregnant. She had travelled to Edinburgh to see a specialist because she was suffering from problems in her pregnancy. It was a brave decision, for the experience would have been extremely slow, uncomfortable and arduous, requiring a journey via Burton-on-Trent to Derby, and then onward by a precarious schedule and numerous stops and starts to Scotland.

While she was in Scotland, Joanna Gresley gave birth in a lodging house at number 14 Dublin Street, a location probably influenced by the Reverend William Douglas, a close relative who lived at an adjacent property. The child was given the first name Herbert after one of his godfathers, and then Nigel, as a link to family ancestors dating back to Norman times. Perhaps pride in their heredity also partly explains the family’s unusually competitive spirit: family members were able to trace their roots back many generations to Robert de Toesni, who accompanied William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. After the Norman Conquest, the family took their name from the local village of Church Gresley, later making their home in nearby Drakelow in South Derbyshire. Gresley’s mother, Joanna Wilson, was a local resident hailing from Barton under Needwood.

The infant Gresley accompanied his mother home from Edinburgh by train. His father was the rector at St Peter’s church in the village, continuing a long-standing family tradition, and it was understood, if not expected, that young Gresley would follow in his father’s footsteps. But from an early age he told friends of his desire to become an engine driver, an unusual ambition for someone of his class in the days before a model railway became an essential possession for a small boy. Given his sheltered lifestyle, it certainly seems odd that he should want to get his hands dirty in some form of industrial occupation. But even as a child Gresley clearly possessed an individual streak that would serve him well in years to come. Perhaps he was influenced by newspaper reports about the great races or was simply fascinated by watching and listening to shunting operations on the nearby colliery branch line. He certainly seems to have been a railway enthusiast from an early age – and there are many cases where a child living next to a railway has gone on to work in them.

Gresley was sent away from Netherseale to attend preparatory school at Barham House, at St Leonard’s in Sussex, before completing his studies at Marlborough College. He enjoyed drawing and mechanical engineering and later won a science prize, distinguishing himself in both chemistry and German. His school reports also mentioned some success as a carpenter and noted that he was ‘very creative and good with his hands’. Little is known of his schooldays, but one imagines he had a typically Victorian education – the type designed to breed serious, solid, able empire-builders.

When Gresley left the college in July 1893 aged 17, he chose not to continue in formal education, finally confirming his unwillingness to enter the clergy. His family must have been disappointed, but they didn’t prevent him going for his chosen career. A young man of Gresley’s undoubted ability had many options, and he opted for a future in mechanical engineering on the railways – a job far removed from that of his father. In October that year, he gained employment as a premium apprentice at the Crewe works of the London & North Western Railway Company, under the watchful eye of Frank Webb, the chief mechanical engineer, and works manager Henry Earl.

St Peter’s Church. (Don Hale)

The Old Rectory at Netherseale. (Don Hale)

When Nigel Gresley first started work, he was paid the grand sum of 4 shillings per week but by the time he had completed his apprenticeship he was drawing a respectable wage of 24 shillings. The LNWR’s Crewe works was a fascinating place then, one of the biggest factories in the country, and one on which the Cheshire town depended. Renowned worldwide, it was as good a place as any for a young man to learn about railway engineering. However, despite the excellence of the factory, the works were frequently called upon to produce a series of bizarre and often poor locomotives. It was a good chance for an aspiring engineer to see what worked, and, just as importantly, what did not. Part of Gresley’s studies coincided with the miners’ strike of 1893–94, and he was able to gauge at first hand the reaction of many working-class railway workers as severe job losses, and then the restrictions of a four-day working week began to hit home.

Following his apprenticeship, Gresley spent time in the fitting and erecting shops at Crewe works, where he gained further practical experience. He then moved to the drawing office of the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway at Horwich, Lancashire, where some very advanced locomotives were being designed. There he studied as a pupil again under John Aspinall, the chief mechanical engineer. At Horwich, Gresley worked in the test room and gained additional experience in the materials laboratory before moving to Blackpool as running-shed foreman. After less than a decade, this young man was starting to move up the career ladder.

In 1901, Gresley met and married Ethel Fullager, the daughter of a solicitor, from Lytham St Annes. She was two years older than her husband and an accomplished musician who had spent time in Germany studying the piano and violin. In the next few years two sons and two daughters were born to the couple, and Gresley became a devoted father, enjoying going on holiday with his children and taking them round the GNR locomotive yards to show them how the great engines were put together.

Through rapid promotion, Gresley then moved to become an outdoor assistant in the carriage and wagon department, transferring to Newton Heath, near Manchester. In 1902, he was made the works manager and then, after a reshuffle, was appointed assistant to the works superintendent. He was one of the youngest people in that kind of position on the railway, and already it was becoming clear that he was set for high office. Just over a year later, Gresley successfully applied for the position of superintendent with the carriage and wagon department on the Great Northern Railway. It was a big leap for him, in terms of both location and the opportunities it offered. He quickly made his mark, however, radically changing the shape of coaches from the fussy clerestory roof (which had a raised strip running down the middle to let light in) to a neater elliptical roof, which made the coaches seem much airier. Thanks to Gresley’s efforts at chassis design, the vehicles rode better, and he even found the time to upgrade the comfort of the interiors. The position carried a salary of £750 a year and seemed a good career move, but in March 1905, and still in his twenties, he moved again.

This time he went to a senior posting at Doncaster works, as subordinate to the well-known and highly respected chief mechanical engineer, Henry Ivatt. The move advanced still further Gresley’s rapid rise up the promotional ladder and provided him with an ideal base from which to learn, watch and wait. It was a highly prestigious position for someone so young: at precisely the right time, he had succeeded in putting his name into lights within a very large shop window. Even Gresley, though, cannot have known how much bigger that shop window would become in less than twenty years.

Of his personal life at this stage, rather less is known. Like many in his position at the time, Gresley seems to have been shy of publicity, leaving us with few indications of what he was really like. What we can say with certainty is that he was a keen sportsman who enjoyed tennis, golf, shooting and occasional rock climbing. He was also a mountain of a man, powerfully built, and with seemingly boundless enthusiasm. He towered above his friends and colleagues, who fondly called him ‘Tim’, a comical abbreviation of ‘Tiny Tim’. Several employees called him ‘Mr G’ or the ‘Great White Chief’, and later, following his knighthood, ‘Sir Nigel’.

This all suggests quite a likeable man, but Gresley was not popular with everyone. He was shrewd, ambitious and some claimed he was an opportunist – he was certainly a ‘master of diplomacy,’ and a man who knew exactly what he wanted and just how to get it. These skills would prove crucial in his rise to the top: pure ability is rarely enough to survive the guerrilla warfare and politics that accompany life in every big company. Henry Ivatt once claimed Gresley was ‘too pushy and too self-confident’. Others claimed he was ‘downright difficult’ to work with; the GNR board, however, welcomed his enthusiasm, honesty and obvious prudence with finance. He was rather old-fashioned and expected staff to speak only when they were spoken to. Yet he seems to have retained a dry sense of humour and loved entertaining friends on golfing breaks.

In January 1910, Gresley’s promising career and active social calendar almost came to a premature end when he received a horrific injury that nearly cost him his leg and very nearly his life. The accident happened while visiting his mother at Turnditch in Derbyshire. He was out shooting rooks with his brother and, as he climbed a large hedge, a blackthorn spike wedged deeply into his leg. The thorn was extremely difficult to extract, and his brother could only remove it with the aid of a penknife, which was normally used to clean his pipe. The wound became infected and both phlebitis and septicaemia set in.