Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

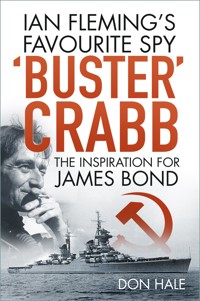

Lionel 'Buster' Crabb was a drinker, a gambler, a womaniser and a lover of fast cars and gadgets. On top of all that, he was a spy, an acquaintance of Ian Fleming and the inspiration for James Bond. A British naval frogman and bomb disposal expert, Crabb worked directly under Fleming during the Second World War at Naval Intelligence and went on to conduct covert operations for both SIS and MI5. Elements from Crabb's dangerous missions and eccentric lifestyle were later incorporated into Fleming's novels. His inventions sparked the role of Q; Miss Moneypenny was based on Crabb's aunt, Kitty Jarvis; and his underwater battle with enemy divers became a crucial scene in Thunderball. During a secret drive beneath a Russian warship in 1957, Crabb disappeared without a trace. One year later, a decapitated and handless body was found, sparking a major row between the government, the secret services and the Admiralty that still smoulders today.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 485

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Jacket illustrations. Front (left): Lieutenant Crabb RNVR, officer in charge of the Underwater Working Party in Gibraltar, 1944, enjoys a cigarette (IWM A23270). Front (right): The Russian cruiser Sverdlov, reputed to have been spied on by Crabb. (Getty Images)

First published as The Final Dive: The Life and Death of ‘Buster’ Crabb in 2007, and in paperback in 2009

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Don Hale, 2007, 2009, 2020

The right of Don Hale to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7524 7186 0

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

To Kath and absent friends

CONTENTS

Foreword

Preface

Prologue

Introduction

1 Missing in Action

2 Family Ties

3 Life at Sea and a Scandal

4 Jack of All Trades

5 Going East

6 Anthony Blunt and Friends

7 Bomb and Mine Disposal

8 Gibraltar

9 Operation Torch

10 James Bond and General Sikorski

11 The Italian Job

12 The Restoration of Venice

13 Friends in High Places

14 International Operations

15 Salvaging a Career

16 The Truculent Disaster

17 Admiralty Business and the Affray

18 Scotland Again and the Sverdlov

19 The Final Dive

20 Classified Information

21 Body of Evidence

22 Cold War Warriors

23 Secrets and Lies

24 Epilogue

Note on Sources

Further Reading

FOREWORD

BY THE LATE NOEL CASHFORD RNVR MBE,1

A FORMER LT RNVR BOMB & MINE DISPOSAL OFFICER 1941–47

It is with great pleasure that I write this foreword. My good friend, the late Commander Gordon Gutteridge RN, OBE, FRSA, frequently worked with Lionel ‘Buster’ Crabb during the Second World War and during post-war years. He probably knew him better than anyone else – yet he knew very little about his past. I too was in the company of Commander Crabb, although rather more infrequently.

Crabb always bordered on the eccentric and remained very secretive. And it was Gordon’s wish for us to collaborate and to try and write the definitive story. Planning meetings had already taken place but sadly Gordon died rather suddenly.

Now, my author friend, Don Hale, whose track record in investigative journalism is well proven, has used his own meticulous research to bring this amazing story to fruition, so that it can now be told in full, in addition to highlighting some amazing links to Ian Fleming’s James Bond spy series of books and films.

Crabb’s ‘final dive’ at Portsmouth in April 1956 was never easy to research but despite often having his inquiries blocked by intrigue, constant cover-ups, and government bureaucracy, coupled with threats relating to the Official Secrets Act, Don has now been able to reveal the true facts relating to this fascinating yet complex case.

Let me confirm Gordon’s last words regarding the ‘Crabb affair’. I quote:

It is, I’m afraid, the story of an ill-conceived Intelligence project, most unlikely to have a useful end product, which was sloppily executed using inadequate resources. The pity is that our rabidly anti-communist, down at heel and blinkered monarchist has been denied, in his advancing years, the regard of his peers and the enjoyment of Scotch and beer chasers with his diving chums. But then, it was as much his fault as anyone, and he never would come in from the cold!

1 Lieutenant Noel Cashford RNVR was awarded the MBE (Military Division) for his wartime work of rendering safe mines and bombs. He joined the navy at 17½ and spent many years involved with interesting, exciting, and yet highly dangerous incidents as a RNVR Bomb & Mine Disposal officer. At 5 feet 6 inches he was precisely the same height and build as Lionel Crabb, and he both trained and worked with him during the war.

Noel also became a well-known, highly respected and much decorated young officer, honoured by King George VI. During his career in the Navy, he made safe over 200 devices, including fifty-seven in just three days, during a colourful six-year career with the bomb disposal squad. Noel was also one of the very first men ashore during the daring Liberation of Jersey in the Channel Islands in May 1945. He worked as a key member of the team with Operation Nestegg and Task Force 135 – when the German-occupied Channel Islands finally surrendered after five harsh years.

PREFACE

Commander Lionel ‘Buster’ Crabb’s most bizarre and mysterious disappearance whilst diving close to three visiting Soviet Navy warships berthed in Portsmouth Harbour in April 1956 probably ranks high amongst some of the world’s most notable conspiracy theory stories.

The vessels had been specially invited to the UK as part of a goodwill visit, with Prime Minister Anthony Eden issuing a strict ‘hands-off’ warning to the intelligence services. Over the past six decades, however, a host of famous authors, politicians, philosophers and other learned scholars have continued to add their own personal opinions about the incident without actually resolving the riddle. It remains a story that, perhaps unlike its subject matter, will never die.

My own involvement came about purely by chance. I happened to be working with a former diving colleague of Crabb’s, the late Noel Cashford MBE, who spent time with Crabb during wartime training with a special Bomb & Mine Disposal Unit.

Noel had asked for my help in publishing his own fascinating memoirs, and as we discussed Crabb’s role in his life, he confirmed that, unbeknown to many people, the case was reviewed by several former senior naval officers some thirty years after his disappearance! I was curious to know just what, if anything, had been discovered, and more importantly, why they failed to publish their findings.

Noel put me in touch with some of his former senior navy colleagues, but the passage of time had unfortunately reduced the numbers of people with personal knowledge of both the man and the case. I did, however, talk with the senior officer who commissioned the review and several of Crabb’s other ex-colleagues, who had mixed views and opinions of the man, his life, and about his disappearance.

One of Noel’s key allies in helping to tell the true story about Buster Crabb was his former friend and associate, Commander Gordon Gutteridge OBE,2 who had recently passed away but had been determined to publish his own findings into the bizarre disappearance of their mutual colleague and friend.

Noel confirmed that Gutteridge, who was once Crabb’s former Commanding Officer (CO), and some of his ex-diving colleagues had spent years unofficially investigating the case. He claimed that much of the paperwork had been scrutinised by a sympathetic ex-navy official during the collation of material for a special historical project.

This review had sparked Gordon’s interest yet again and he worked with others and continued his quest for the truth until his dying day. His summary played an important early role in my own inquiries and led to interviews with other important contacts.

In his papers, he told Noel:

I was asked to help investigate the Crabb Affair. I added a fair amount of research to my own personal knowledge to produce a rough draft. It has stood the test of time and no one has succeeded in faulting it.

I am as near as certain that this is the true story of what actually happened. This is my version and I have a lot more material available. With Crabb, this is ancient history but still seems to be of considerable interest. A dozen books have been written about him – but they were ALL phoney.

Noel, and Gordon’s widow Gill, then later and willingly forwarded all the relevant documentation to me and asked if I would collate the information and finish the task. I then spent many months reassessing his notes and managed to locate and correspond with many of Crabb’s former friends, naval colleagues and ex-senior officers to add to, and/or verify/update, their own personal accounts.

It proved to be an immense and very difficult task, rather like trying to find a lot of missing jigsaw pieces from a complicated and secretive pattern. Gordon’s honest endeavours, however, helped to highlight and corroborate Crabb’s colourful life and career.

It has resulted in a warts-and-all account of Crabb’s life and includes many previously unknown facts about his secret war work, the search for the crashed plane of Polish General Sikorski in the waters around Gibraltar, his dangerous missions in Palestine, and later his peacetime diving exploits for several missing submarines, and profitable links with the intelligence services. It also confirms how he helped teach Lord Mountbatten to dive.

Gordon first met Crabb in Gibraltar in April 1943 and they became good friends. Gutteridge was his commanding officer. They worked together on many difficult and dangerous assignments for the Undersea Countermeasures and Weapons establishment and remained friends until Crabb’s death following his final dive in 1956.

Gordon dealt with the recovery/disposal of mines from Suez, Alexandria and the Western Desert ports to Benghazi. Later in 1943, he became port harbour master and then Bomb & Mine Disposal officer at Poole, Dorset, covering the South Coast from Southampton to Portland.

In August 1944, he joined ‘P’ Parties as a specialist in mine recovery and disposal. These were experienced naval diving groups responsible for clearing enemy mines from European ports to make safe for Allied shipping.

One of his final wartime tasks included the clearance of the port of Dunkirk. In 1957, he was awarded an OBE for making safe a dangerous mine at East India Docks, London, with his colleague Lt Mark Terrell.

Gordon’s personal notes were originally prepared about 1990 but were constantly revised and updated as further information was added. This latest batch of documents was revised again in 1998, but he continued to add other private letters, newspaper cuttings and other relevant material to his portfolio. Commander Gutteridge died in 2002.

Further inquiries resulted in my contacting additional former friends and family members, and it soon became clear that despite government restrictions they still remained determined to seek the truth about Crabb’s final dive and his top-secret mission. They seemed particularly concerned at press reports and repeated allegations that Crabb may have deliberately defected, turning his back on a country that he had served with distinction for decades. Others queried whether he had perhaps outsmarted everyone and may indeed have operated as a Soviet spy or double agent, perhaps in a similarly deceptive fashion to some of his former friends and family associates such as Blunt, Burgess, Maclean, Blake and Philby – and perhaps even Lord Rothschild!

I must admit, I found all the supposed defection claims hard to believe. There seemed little or no supportive evidence, and I queried why, if any of this were true, the Russians had simply and unbelievable failed to capitalise on a remarkably persuasive achievement by not triumphantly parading Crabb through Moscow’s Red Square – as they had before with other acclaimed double agents. I also examined numerous false claims about these allegations.

I also found it strangely curious that the British Government have deliberately and continually blocked any further examination of Crabb’s operational files for such a long period of time, and why so many ex-navy personnel say they have been threatened by the establishment to keep quiet, and remained concerned about the Official Secrets Act, and of potentially losing their valuable pensions.

In addition, I found it difficult to accept, understand or even appreciate the need for such extreme secrecy after all this time, so encouraged by their obvious desire to finally set the record straight, I accepted a fresh challenge to make further investigations.

Regrettably, some of the additional people that I previously interviewed, including my original source Noel Cashford, are no longer alive, but I would still like to thank them and their families for their co-operation in helping to expose and reveal some key elements to this extraordinary affair. I believe I have since identified most, if not all, of the missing names, and have also highlighted several other important factors from this strange puzzle. I fully believe my work will now explain the many hows, whens, and wherefores of a truly fascinating case.

2 Gordon Gutteridge OBE served in 1939–57 in the Royal Navy, and the Royal Navy Scientific Service. For most of that period, he was in command of units dealing especially with magnetic and acoustic underwater mines.

Eventually, he became responsible for the development and trials of diving and mine investigation equipment. His acquaintance with mines first began in early 1941, when as a sub-lieutenant, Royal Naval Reserve, he volunteered for, and was appointed to, the post of Bomb & Mine Disposal officer on the staff of Rear Admiral (Alexandria, Egypt).

PROLOGUE

DIVING DEEP TO DISCOVERTHE REAL ‘JAMES BOND’

For more than two decades, Commander Lionel ‘Buster’ Kenneth Philip Crabb GC, OBE, RNVR, was Britain’s best-known frogman spy. A number of his highly dangerous undersea operations were later publicised throughout the world – with some even made into films and TV documentaries. After the Second World War, he worked in secret for the intelligence services and was also employed on several occasions as an advisor to authenticate cinematic wartime action films, including The Cockleshell Heroes, and in 1958 – just two years after he mysteriously disappeared – one of his own exceptional exploits in Gibraltar during the war was made into a major feature film called The Silent Enemy with an all-star cast including Laurence Harvey, who played the role of Crabb, together with Dawn Adams, Sid James, John Clements and Michael Craig.

His wartime heroics quite rightly earned him two national awards for outstanding bravery and devotion to his King and country. He became a loyal servant to certain members of the Royal Family, including Lord Louis Mountbatten, and the Queen’s cousin Anthony Blunt, and was also a friend, colleague and confidante to top politicians, naval officials, the rich and famous of the day, and even to several members of the notorious Cambridge ring of spies.

It is now accepted that Crabb’s character, and many extracts from official reports of his brave and often secret missions, eventually became the inspiration to Ian Fleming – his former Naval Intelligence boss – for a series of Cold War spy books relating to his fictional hero James Bond. Although a mile or more apart in terms of physique, Crabb’s controversial activities in Gibraltar, Italy, Egypt, Israel and elsewhere in the world provoked many ideas for his potential storylines, and within this book I reveal numerous fascinating links to Fleming’s exceptional 007 character.

Crabb was a heavy drinker, a compulsive gambler, and an expert in a varied range of card games. He was also a keen smoker (mainly of strong Turkish cigarettes), and he loved women and fast cars. The latter hobby of driving fast open-topped sports cars was probably enhanced and encouraged by his cousin Kenneth Jarvis, who was a top racing driver and experimented with a host of motor gadgets.

Crabb was very laid-back and nonchalant. He revelled in telling people about his colourful career and had travelled the world gaining wartime experiences in many God-forsaken places, and he had an intimate knowledge of espionage and underwater weaponry.

For many years he worked the London clubs and often frequented some of the best restaurants in town, mingling with the rich and famous of the day. At times he worked for both Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) and MI5 on covert intelligence operations, both throughout the war and for many years afterwards.

Crabb even became part of Lord Mountbatten’s handpicked and specialised unit during the Second World War and later during the Cold War, involved with many unofficial and secretive underwater operations. And in addition, during his controversial career, he also gained valuable experience working under infamous, yet important characters including Anthony Blunt, Harold Adrian Russell ‘Kim’ Philby and Ian Fleming.

Some of Crabb’s antics for unusual experiments were also incorporated by Fleming as ‘Q’ within a secret test laboratory, where Crabb would help to invent, test and develop a unique range of underwater listening and photographic devices, and sabotage weaponry.

During the latter stages of the Second World War, Crabb took instructions directly from Lord Mountbatten during a search for Nazi gold, stolen treasures, and to help capture German war criminals. During one particular operation he discovered some Nazi war bunkers and found evidence of invasion plans.

It was probably during a series of debriefs and drinking sessions with his other wartime navy boss Ian Fleming that Crabb first revealed facts about his Far Eastern gun-running experiences with the anti-communist leader Chiang Kai-Shek in the 1930s, and about his work with Morris ‘Two Guns’ Cohen, a notorious villain and bodyguard, who was the inspiration for Odd Job in the book and film Goldfinger. Cohen, apart from his two-gun party trick, also wore a tall hat with a sharp metal-spiked brim that he would hurl at opponents to cause maximum damage.

***

Crabb’s aunt, Kitty Jarvis, was also Fleming’s inspiration for Miss Moneypenny. She helped to bring up the young Lionel Crabb. She worked at MI5 and was a personal assistant to Anthony Blunt at the War Office during the war. Blunt was then involved in sabotage and counter-intelligence, and amazingly she told of many meetings and visits from the likes of fellow Cambridge and Soviet spies Kim Philby, Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess, with many often visiting her special MI5 flat for celebrations.

Kitty was known as ‘Mater’ in the War Office. She also had a prominent hat stand in the corner of her office where visitors would try to fling their hats onto a peg. Fleming worked further along the corridor in Naval Intelligence and would often witness these antics to great amusement.

Kitty’s flat at 12 Douglas Mansions, Mayfair, was partly paid for by the intelligence services where she could entertain a range of VIPs, and her phone number even ended in 007. The number 7 was actually claimed to be a lucky number for both Crabb and Fleming. During the worst of the Blitz she was later moved to a room at the Strand Palace Hotel, then later to a suite at the Ritz.

Other potential spy inputs for Fleming included the use and knowledge of the Cavendish Hotel in London, run by Rosa Lewis and Maitland Pendock (a Special Intelligence officer). The hotel was sometimes used for ‘honeytraps’ and contained double-sided mirrors, hidden microphones and important surveillance equipment. Lionel Crabb worked there pre-war to gain experience as a barman, learning about a range of cocktails, and this was where he first met Anthony Blunt, later being employed in his art gallery, before their wartime associations.

During 1943, another of Crabb’s wartime adventures was eventually incorporated within Fleming’s Bond novels. There was a plane disaster – or more likely a sabotage and assassination plot – on the Polish leader General Sikorski. His plane crashed into the shallow waters off Gibraltar, killing the general and his daughter and colleagues. Crabb was first on the scene and tasked to rescue some secret documents that could possibly endanger the support of the Allies. Ironically, and working then under the direction of both Kim Philby and Anthony Blunt, he was ordered to dive with colleagues to locate and confiscate any key documents.

This episode of his life and his work in counter-espionage based in Gibraltar during the Second World War was where he first gained deserved plaudits for his daring work in constantly thwarting teams of crack Italian saboteurs, who were trying to destroy Allied shipping by securing limpet mines from specially built Italian submarines called Charioteers.

Crabb’s work in successfully countering a number of these vicious attacks on Allied shipping probably helped to change the course of the war, earning him an OBE, the George Medal, and a coveted place in Mountbatten’s secret intelligence unit.

As the war progressed, Crabb was eventually credited with persuading many members of the Italian Tenth Flotilla to change sides, and to work with him to make places such as Venice safe again from Nazi booby traps and mines.

A scene based on the original Sikorski drama, this time utilising a crashed jet, was later incorporated in the film Thunderball but moved to the Bahamas, where it became a race against time to seize nuclear weapons from an international terrorist organisation – rather than a true-life battle by Crabb and his team against Italian saboteurs.

An additional bonus for Fleming was Crabb’s identification of a specially adapted ship with a modified hull to help secretly launch enemy divers, which was spotted by him just across the sea from Gibraltar in neutral Spain.

An interpretation of these facts later became another important part of Fleming’s script. Further intelligence reports, and the suspicion of a fascinating wartime plot about this incident, eventually came to Fleming’s attention shortly after the war, when his lover Krystyna Skarbek (a.k.a. Christine Granville), who had been one of his wartime operatives with SOE in occupied France, was brutally stabbed to death at the Shelbourne Hotel in Kensington after she allegedly found some vital evidence about the Sikorski crash. As a tribute to her, Fleming later used her beauty and courage to create the Vesper Lynd character in the Bond novel, Casino Royale. Quite bizarrely, about five years later a former friend and confidante of Krystyna, Teresa Łubieñski, a Polish countess, was also found stabbed to death at Gloucester Road tube station in May 1957, again after allegedly discovering similar information about the mysterious wartime incident.

Many other aspects of Crabb’s work, his inventions and his bravery also feature from time to time within Fleming’s work, including the use of limpet mines, and a number of special underwater gadgets and explosive devices.

Lionel Crabb, the frogman spy, was a natural diver. He was brave and completely fearless. It was just his own personal demons that occasionally brought him out in a cold sweat. He was an undisputed war hero and an experienced spy, and yet remained a complex character.

He was a loner who suffered from recurring bouts of depression, and constantly retained a rather unfortunate passion for gambling, alcohol, tobacco and women – and not necessarily in that order. Commander Crabb’s diving skills and vast experience of intelligence operations and undersea warfare techniques were legendary, and he could no doubt have influenced, inspired and educated countless generations of future naval and diving recruits.

I was delighted to be given the unique opportunity to study his family background and examine the true workings of one of Britain’s most successful and highly decorated espionage agents.

Crabb was undoubtedly a quite unusual, if not unique, character. At times, he was stubborn, pig-headed and foolish. His early life and career became shaped by a series of family dramas and ultimate tragedies. If things had turned out differently, he could even have been raised in Australia, or become the heir to a wealthy corn merchant’s business, or inherited a substantial property portfolio.

It was not to be, however, and the future of a very young Lionel Crabb was realistically determined during the First World War when, as an orphan, he and his mother Daisy had to rely heavily on the support of close but wealthy relatives, Frank and Kitty Jarvis.

Kitty later played a prominent role in his career due to her own work within the intelligence services, and her friendship both with Anthony Blunt and Ian Fleming no doubt helped to open a few doors for the ambitious young man.

This occasional access to the Jarvis family offered young Lionel a taste of the ‘good life’ and gave him a determination to better himself. Crabb’s writings tell of his early years of travelling the world and how he tackled a succession of crazy dead-end jobs before finally finding his feet as a trainee spy, gun-runner and mercenary in the Far East before returning back home to try and tackle the Nazi threat.

Lionel though was never satisfied with his lot, and yet through his famous the Second World War exploits he became both well-known and well-connected. His legendary status was no doubt enhanced by his sudden and mysterious disappearance in 1956, and it seems quite incredible that both his life and work continues to attract worldwide interest, controversy and speculation more than sixty years later.

Some reports claim he was shot, stabbed, electrocuted, strangled, kidnapped, captured or that he had deliberately defected to the Soviet Union from Portsmouth Harbour. Others suggest he allowed himself to be taken and worked for decades in Russia as a double agent and Red Navy diving instructor.

As the years since his disappearance increase, so do the exaggerated tales from certain ex-colleagues, many who of whom should have known better, merely lining their pockets from telling imaginative tales about a man they claimed still existed somewhere behind the former Iron Curtain. The hardest part for me during my years of extensive investigation has been to sort the wheat from the chaff. I was also keen to find the answers to a number of other anomalies and conundrums about his early life. In particular, I wanted to know why a man who supposedly hated exercise, and was admittedly a poor swimmer, with an acknowledged eye defect, should volunteer for a succession of highly dangerous underwater missions.

In addition, I also wondered what had transformed this once modest, reserved youngster into a fearless and unstoppable war hero constantly prepared to risk life and limb for his country. I became intrigued as to whether he had been manipulated, persuaded or deliberately coerced into adopting this shady world of international espionage, and counter-espionage, and whether his family links may have enhanced or at least contributed towards this career path.

I was fascinated too by his illustrious war record, and of diving with fairly primitive equipment for long periods of time – generally in freezing cold, dark, dangerous waters in search of enemy mines, booby traps and a host of other explosives and potential dangers. How did he stand extreme air and water temperatures and yet still retain his concentration?

I wanted to look behind and beyond the apparent facade of this extraordinary man, and if you will excuse the pun, as he was a former navy diver and a Bomb & Mine Disposal officer, I wanted to see just what made him tick!

It was clear that many aspects of his life and career were still riddled with myths, rumours and speculation. I wanted to determine which, if any, were true, and particularly investigate the key events leading up to his disappearance, and the later finding of a controversial and disputed headless and handless body washed up more than a year later in Chichester waters.

The following chapters are based on my personal interviews, case reviews, secret files, private letters, notes, emails, family archive material, his mother’s scrapbook, unique photo albums, and from many other personal recollections. They also contain several important extracts from official and unofficial records. I believe that my investigation over four years or more not only confirms some interesting and previously unknown links to the creation of the James Bond character, but now supported by new factual and compelling evidence, I believe that I can finally reveal the truth about the life and death Buster Crabb, who was undoubtedly a quite exceptional, and unconventional character of whom James Bond would have been proud.

INTRODUCTION

THE BEGINNING OF THE END

In the spring of 1956, Lionel Crabb received a surprise and rather urgent summons to meet with Lord Louise Mountbatten, the First Sea Lord, at Cowdray Park, Sussex. He was invited to undertake a special joint (and highly secretive) mission organised by the British and American intelligence services.

A few weeks later, Crabb began visiting and corresponding with friends and relatives, many of whom he had not seen for many years. In a brief note to his mother Daisy, he confirmed that he was ‘off to do another little job in Portsmouth’. He instructed her to destroy the note once she had read it. And unusually, just before this particular assignment, Lionel even asked his fiancée, Pat Rose, to accompany him on the train south.

In a letter she explained:

On the journey down to Portsmouth I threatened to break off our engagement if he didn’t tell me what was really going on. Finally, he admitted he was going to look at the bottom of a Soviet cruiser. At Portsmouth, Crabbie said we couldn’t stay in the same hotel because he had to leave early to meet with a Matthew Smith, an American agent. He said if he didn’t phone tomorrow, he would call sometime in the evening. That was the last I ever saw of him.

Crabb’s Final Mission

This is a reconstruction of events leading up to Crabb’s final dive on Thursday, 19 April 1956 at 6.50 a.m. It is based on exact testimony from official documents, naval reports, and from direct interviews with several people who were either with Crabb just before the mission began, during it, or from people who were involved in the aftermath of the event.

For the umpteenth time, the two naval officers synchronised their watches and checked their equipment. It was just a few minutes to 7 a.m., and to the start of another difficult and dangerous mission. The pair sat hunched in a small launch ideally positioned and anchored about 80 yards offshore. There was a freshening wind, and yet a low swirling mist still danced, twisted and hovered just a few inches above the choppy waters of Portsmouth Harbour. It was exceptionally cold and damp that day, and the bitter chill made both men even more anxious about the task in hand.

Commander Crabb was an experienced diver and was already dressed and prepared for action. Crabb wore his favourite Heinkel diving suit. His colleague, Lt George Albert Franklin – better known as ‘Frankie’ – checked his colleague’s oxygen tank and watched as the diver puffed away on another hand-rolled cigarette. Crabb seemed unusually nervous that morning and coughed and spluttered.

Franklin tried to distract him and to help take his mind off matters, he quickly handed him the new Admiralty underwater test camera. It was a brand-new secret gadget that even ‘Q’ would have been proud of within Ian Fleming’s Bond series. Crabb took one long, last drag of his cigarette before hurling the still smoking stub over the side and grabbing the camera firmly with his right hand.

Franklin was a good friend and a former diving colleague, who assisted Crabb and prepared him for this latest mission, helping his pal to put on his diving suit, whilst he himself was dressed as a ‘civvie’ in warm casual clothing, a dark-coloured woolly hat and waterproofs.

The attendant flicked the primer switch on this experimental new camera, which Crabb was expected to use to film the underside of the rudder, hull and propellers of some visiting Soviet warships berthed in the harbour. They were ordered to secretly test the device and were only given basic operating instructions.

Franklin checked his watch again; it was now 7 a.m. precisely. As a final gesture, and almost instinctively, both men turned their heads and looked about to check for signs of anything out of the ordinary, but with the strong wind whistling about their ears and the constant splashing from whipped waves against the side of their launch, it was impossible to distinguish anything other than the usual dockyard noises.

Crabb gave Franklin a thumbs-up sign and slipped quietly and efficiently over the side, falling backwards into the dark foaming waters. The mission was finally under way, and the attendant watched as a trickle of small bubbles drifted slowly towards their intended target.

Franklin then turned, scanned the shoreline and waved towards his American minder, Matthew Smith, a CIA liaison officer. It was Smith’s job to act as a lookout and to guard their spare gear, and to keep a discreet but watchful eye out for any unexpected activities.

He was standing close to the King’s Stairs, a small series of stone steps that led steeply down to the waters. Franklin thought he looked like a shadowy, sinister figure, set against the dark, gloomy background of the quayside.

On the launch, Franklin had to hold tight as it rocked violently in the buffeting wind, and a heavy swell from the ebb tide. He wiped his watering eyes and tried to clear his head. He soon wished he was back in the warmth of his secure unit at the naval training establishment at nearby HMS Vernon. He looked again for Smith as the waves battered the launch, each time clattering and stabbing at some bundles of spare parts as they rattled against the wooden struts.

Smith was tall and slim and wore a thick patterned overcoat. As Franklin gazed across, Smith appeared to be stamping and shuffling his feet to keep warm. As the mission began, he raised his hat towards the launch in acknowledgement, but he now seemed to be showing some slight signs of nerves, as he suddenly stopped his actions to light a second or third cigarette.

It was at least twenty minutes before the diver returned. There was a sudden surge of bubbles on the port side, followed by some snorting and hissing sounds, and Franklin watched anxiously as Crabb seemed to be desperately trying to hang on to the side of the boat. As Crabb lifted his head above the waves and grabbed for the support rail, the launch rocked again, causing Franklin to fall back hard onto his backside.

Until that point, the mission had followed a similar pattern to the brief test dive the day before. This time, however, Crabb seemed flushed, impatient and out of sorts. He was breathing very heavily and was constantly out of breath. He snapped back at his colleague and demanded more ballast for his footwear. Crabb also ordered Franklin to check his oxygen levels again. It seemed that very little had been used. He checked the dial and told the diver all seemed well.

Crabb, though, was angry. He grimaced and threw the camera back into the boat, cursing the new equipment. Crabb complained of limited visibility, a dreadful stench from the water, and the bitter cold chill of their early morning adventure.

Franklin, though, was very concerned for his friend’s safety in those turbulent conditions and nervously asked his colleague if he was well enough to continue. Crabb rejected any suggestion of aborting the mission as both understood that timing was critical. Desperate to return, the diver tapped his mouthpiece against the side, spat out some seawater, and then clung on for another minute or so. He was still wheezing hard. He also shook his head from side to side, as if he was trying to clear some water lodged in his left ear. He then pinched his nose and blew hard until his ears popped.

As Crabb struggled for air, his mind probably wandered back to the start of the day, when he was awoken in pitch darkness at 5.30 a.m. by the shrill sound of his alarm clock at the nearby Sallyport Hotel. It had only seemed an hour or two since he had returned to his room from a boozy night out with friends in a local bar. Crabb, as usual, had downed far too many drinks, and at times felt light-headed and slightly dehydrated with a dry mouth.

He had stayed at the hotel with Smith, who occupied an adjacent room on the top floor. Through Crabb’s small window, he had a bird’s-eye view of the harbour and could just see the Soviet ships in the distance. In his anxiety to start work, Crabb knocked on Smith’s door before descending the stairs to listen to the early morning shipping forecast in the hotel’s reception. He recalled punching the air when he heard there would be more fog in the Channel and hoped it would spread to cover his daylight mission.

Smith and Crabb then left on foot and travelled a short distance to the dock gates where, as previously arranged, they met up with Police Superintendent Jack Lamport, and a CID colleague, who escorted them through the security checkpoint.

As they cleared the gate, Lt Franklin arrived and drove the party the few hundred yards across to the King’s Steps, which led directly down to their launch. Franklin had already stowed much of their essential gear, before dragging some heavier items from Crabb’s nearby storage shelter. The policemen bid them good luck and left before Smith gave Crabb and Franklin a final briefing.

Now on the dive, Crabb’s hands suddenly began shaking. Torn between his desperate need for a cigarette and the knowledge that he must continue, Crabb decided he just wanted to get the job done quickly and go home. He told Franklin he was OK and, biting hard on his mouthpiece, quickly disappeared back into the murky depths.

Ahead and beyond, perhaps no more than a few hundred yards or so, and partially blanketed in this intermittent mist, the attendant could just make out the rough outline of three visiting Russian warships. Despite being delayed by thick fog in the Channel the previous day, they had hastily opted to berth alongside the Southern Railway Jetty less than twenty-four hours earlier.

The principal ship was a very modern cruiser, the Ordzhonikidze (roughly pronounced as ‘Our Johnny Kids You’), together with her accompanying sister ships, the destroyers Sovershenny and Smotryashchi. The vessels had brought Soviet Premier Marshal Nikolai Bulganin and Communist Party Chief Nikita Khrushchev to Portsmouth for a unique goodwill visit at Prime Minister Anthony Eden’s express invitation.

The Ordzhonikidze was a sister ship to the Sverdlov, another powerful and highly manoeuvrable Soviet cruiser that had also visited these same British waters less than a year before, taking part in a special international naval review. Ironically, and during that visit, Cdr Crabb and another diving colleague had inspected her hull too, recording vital details about her unique turning capacity.

The Soviets, however, had since been made aware of Crabb’s previous unauthorised visit, and were now on notice of something similar happening again. This time, unlike the previous solo visit of the Sverdlov, all three visiting warships were now berthed tightly together, mooring directly alongside each other in a secure dock area.

***

Time passed slowly that morning and Franklin, who worked for the HMS Vernon diving school, was already beginning to regret his involvement. This mission was obviously NOT, as Crabb had previously suggested, going to be a quick operation. And as he stared across towards the Soviet ships through highly powerful binoculars, his vision was impaired by a constant glare off the water, as the first few rays of the early morning sunshine began to shimmer along the rippling surface.

The mist, though, was rapidly diminishing, and as he adjusted his viewfinder, his shoulders suddenly tensed, and his arms stiffened. For a brief second, he felt his heart skip a beat. Somewhere during a small gap between the three ships, he thought for a split second that perhaps he had glimpsed some large dark shape – maybe even a diver – bob to the surface, and then quickly disappear.

As he wiped his eyes again, Franklin also noted some activity on the foredeck of one of the Soviet vessels. In addition, there appeared to be a slight disturbance in the water, but as he stared again, it settled. He checked his watch. It was just after 8 a.m. He knew his colleague carried less than two hours of oxygen, and realised Crabb was well past his peak, and that his friend smoked heavily, and stupidly, he had downed far more than his fair share of booze the night before.

For another hour or so, his anxious eyes scoured the surface of the water for any further signs of life. Franklin’s hands became ice cold, and he began shivering and shaking uncontrollably. He was also very confused and frustrated. He had a gut feeling that something had gone terribly wrong, but he had his orders to wait. He wondered if the Soviets had seen, attacked, or even captured Crabb?

He thought the latter options highly unlikely, especially in British waters, but then considered that his friend might have encountered a problem with his equipment. In addition, he knew his breathing hadn’t been too good that morning. He wished Crabb had heeded his advice not to continue. Worse still, and knowing the perils of diving in this particular rather hazardous harbour, even in daylight, Franklin then considered Crabb might even have become snagged on some underwater obstruction.

He considered an urgent rescue dive, but knew it was against Crabb’s direct orders, and then asked himself where should he start to search? He looked to Smith for guidance but was unable to spot him and felt he should have been doing something more to help. He decided to haul in the small anchor and rapidly began patrolling the area in his launch.

Franklin went as near to the Soviet ships as he dared, but after another ten minutes or so, he returned to his original position. He knew he faced a hopeless task, and as the minutes raced by, he began to appreciate the significance of the problem, and soon realised the Admiralty would be highly embarrassed and the government compromised.

Finally, at 9.15 a.m., more than two hours after the start of their operation, Franklin signalled to his American colleague on shore, packed up the kit, and reluctantly abandoned the mission. The overall aspects and aftermath of this highly embarrassing incident were eventually debated in Parliament. It caused complete mayhem within the ‘establishment’, and led to a massive breakdown in Anglo-Soviet diplomatic relations. And, not too surprisingly, it curtailed Franklin’s naval career, and led to the removal of some senior naval personnel, top politicians and key civil servants.

For several months, heads rolled left, right and centre. It also triggered a quite extraordinary and unprecedented shake-up of the intelligence services. These pertinent factors, coupled with the equally disastrous Suez Crisis just a few months later, eventually led to the downfall of Prime Minister Anthony Eden and his Conservative Government, and initially resulted in a Cabinet-recommended 100-year prohibition on the examination of all, or any, of the official documents relating to this matter.

CHAPTER ONE

MISSING IN ACTION

On a bitter cold day in March 1918, a chill wind seemed to whistle through nearly every crack and crevice of the small house in Streatham, south London. Beatrice Crabb was well wrapped against the elements. She wore an old cardigan draped around her shoulders, a pair of warm mittens on her hands and two pairs of woollen socks on her feet.

Whilst pulling at the curtains to lessen the draught, she suddenly stopped and dreamily watched as the cold winter sun slowly disappeared below the horizon, scattering a spectacular blood red and pale blue haze of colour across the tops of the fir trees by the park. She knelt down and put a few of her 9-year-old son Lionel’s toys away in an old tea chest. Just like many other housewives and mothers of that era, Beatrice was just trying to keep busy to take her mind off her husband’s absence during the First World War.

A few minutes earlier, she had begun preparations for supper. The table was set, with three sets of placemats, knives, forks and spoons. Several pans bubbled and hissed on the stove in the kitchen, and some plates were being warmed in the hearth. There was a strong, warm smell of vegetable broth and onions, with cups and saucers prepared for when the kettle boiled. Beatrice always kept her house spotlessly clean. She also maintained a demanding schedule.

She worked part-time at a local bakery while raising her very active young boy – mainly on her own – while her husband Hugh served his country somewhere on the Western Front. Unusually, she had not heard back from him for more than a fortnight. He normally wrote several times a week but she knew that with this freeze, the troops were probably sheltering whenever they could.

Beatrice always kept a place at the table for Hugh just in case he returned home on unexpected leave. Beatrice was tall, attractive and slightly old fashioned in her manner and appearance. She was, however, a very determined young woman with a positive outlook on life.

She stood for a moment at the corner of the room and smiled as she watched Lionel at play. He was well away in his own private world, completely oblivious to any other distraction. She listened as he began to bark out imaginary orders to a collection of brightly coloured lead soldiers. In one hand he held a wooden sailing ship, delicately hand-carved by his father during a brief spell of home leave just before this last ‘Big Push’. For Lionel this ship was something special. He thought it contained magical qualities and provided essential covering fire for a land-based assault by his toy soldiers. He carefully positioned them around the back of a table leg in support, waiting for the command to attack.

He called the red soldiers ‘infantrymen’ in recognition of his father. This latest battle may have been a fierce re-enactment of some major skirmish on the Turkish mainland as read out by Hugh from newspaper extracts, praising the bravery and heroics of his colleagues. Beatrice yawned and suddenly felt very tired.

She stroked her long dark hair back behind her ears and pulled it into a ponytail. She tied it back securely and stared back into the room. Then she pulled another cloth from her apron pocket and started to wipe the top of the mantelpiece, before dusting some ornaments, and folding her ironing. She walked back towards the kitchen, knowing the kettle would soon be ready. Lionel looked up just as she left the room but remained silent. His mind was still occupied with military and maritime adventures.

Lionel could hear his mother rattling pans and cleaning up in the kitchen when suddenly there was a very loud knock on the door. Beatrice shouted that it was probably for him, but said he couldn’t go out, as it was too late and too dark. Lionel looked down the hallway, and when she opened the door, he could see that it was a young telegram boy, who held out a small brown envelope, whilst trying to balance his bicycle. Lionel knew the boy. He was a member of the local Sunday school, and was also the eldest son of a friend of his mother’s. She had kept telling Lionel to join this particular lad at church, saying he always set a good example.

He could see his mother staring at the boy. For some reason, she didn’t want to accept the envelope. He couldn’t understand what was happening. His mother seemed shocked and surprised that he had come to her house. He heard her ask the boy if he had come to the right address. He couldn’t hear his reply. He saw the boy turn the envelope over to read out: ‘No. 4, Greyswood Street, Streatham. Mrs Beatrice Crabb?’ Everyone in the street knew his mother as ‘Daisy’. Lionel told his friends that she had always hated her real name.

‘Mrs Beatrice Crabb?’ asked the boy again. He saw his mother hang her head. He thought she looked pale even in the reflection of the streetlight. She held out her hand again, and watched as the messenger turned away. She began to read the message. Lionel could see that she was struggling. Her hands were shaking. She automatically stepped back inside the house, and into the brighter light of the oil lamp in the hallway. She turned, smiled and patted Lionel on his head. He could see tears in her eyes. He asked her something but she didn’t hear him and just muttered: ‘No. It’s not for you.’

Daisy read the short message again in case there had been some terrible mistake. The messenger boy asked if there was any reply. ‘No, no reply.’ She then gripped the boy’s arm and asked him to let his mother know. She closed the door and stepped back into the kitchen. She sat down heavily on a wooden stool and sighed. Lionel instinctively ran into the kitchen and stood next to her. He could see the top of the note. It gave an address at the War Office. It also gave her address as ‘next of kin’ and stated: ‘To Mrs Beatrice Crabb, we beg to inform you that No. 25894, Lance Corporal Hugh Alexander Crabb, of the 8th Battalion East Surrey Regiment, has been reported missing in action at Pozières.’

Beatrice couldn’t read any more and screwed up the telegram in her clenched fist. Lionel didn’t know what to do or say. He was upset because his mother was upset, but didn’t really know why. His mother grabbed and hugged him tight. She held him so hard that he could hardly breathe. Neither said a word and tears streamed down their cheeks. After a few minutes she just pushed him away, wiped his face, and calmly said: ‘Your father’s missing!’

***

More than thirty years later, when Lionel was sitting in a bar swathed in cigarette smoke, he would tell colleagues the story of how he learned of his father’s death. He said it had been the worst moment of his life. His eyes filled each time he told the story and he said he could still feel the same sense of breathlessness each time he faced a difficult dive. Once, he claimed he had even seen the ghostly face of his father, Hugh Crabb, rising from the ocean depths.

Lionel said his mother never really gave up hope. She spoke about him constantly. As the youngster began to make his way in the world he recalled how his father talked of witnessing many acts of courage on the battlefield, and of how he had tried to cope with the loss of friends and comrades while serving his ‘King and Country’. He said his father had written many letters home on behalf of fallen comrades, and mentioned his familiar phrase, the need for a ‘stiff upper lip’. Just how much this really affected the early life of Lionel Crabb, one can only guess. Hugh’s body was never found.

Some said it was a token final surge, which gained a few hundred yards in yet another blood-soaked, shell-holed battlefield. Others claimed it was a successful counter-attack. Crabb’s father and numerous others never even enjoyed the dignity of a proper family funeral. Instead, the Commonwealth Graves Commission at Pozières engraved his name among 14,644 others on the grand Memorial to the Fallen Heroes. Hugh’s date of death is shown as 22 March 1918. He was just 40 years old.

For Daisy Crabb, it took a few more days for the full implication of the news to sink in. At 37, she was a war widow and a single parent. She worked part time as a baker and later obtained additional temporary work as a cook to a large family, working at times in the early morning and late evening. Occasionally, both jobs overlapped and Lionel was left with friends, neighbours or relatives.

Daisy had little money but refused to accept charity, or sympathy. However, she knew she would eventually require some financial support for Lionel’s education. Her own parents and grandparents had long since died. Daisy remained thankful for the generous support of close relatives, in particular the Jarvis family, headed by her wealthy cousin Frank Jarvis and his wife Florence, who was better known as ‘Kitty’. Other support came from Frank’s sister, Kate, also from Bessie and Ada, all fondly referred to as ‘Aunts’. Daisy was related to the Jarvis clan via her grandfather Joseph Adshead, who married Harriett Ross, an aunt to Frank’s father Edward. The powerful influence of the wealthy Jarvis family featured strongly in Lionel Crabb’s early upbringing – and remained throughout much of his life.

CHAPTER TWO

FAMILY TIES

The predicament of the Crabb family at the end of the First World War was no different from countless others of that time. As Lionel later told colleagues, by the end of hostilities in November 1918, half his classmates had lost the main ‘breadwinner’. The cruelty of losing a husband so close to the end of the war was not lost on Daisy, who contacted her cousin Kate, also bereaved of her partner. For a while they comforted each other and shared the care of their children but for society as a whole the loss of almost a whole generation of young men was incalculable. Daisy admitted to a few long periods of depression, and the odd drinking spree, which she always tried to hide from Lionel.

How different life might have been if Hugh and Daisy’s elder brother John had escaped from the doom and gloom of Edwardian London just a few years earlier. In 1913, the men had set off for Australia in search of a new life, having read about fantastic opportunities in the New World. They intended to find accommodation and employment ‘Down Under’ before sending for Daisy and young Lionel. However, their exploratory trip was interrupted by developments in the Balkans, with expressive posters of Lord Kitchener summoning young men to war with ‘Your country needs YOU!’ It was believed the conflict would all be over by Christmas.

At 35, Hugh thought he was too old to fight. Yet, he was reluctant to be seen as a coward and saw just how many others were eager to take the ‘King’s shilling’. This included John, who was four years younger. John was very keen to sign up, so they decided to enlist together, and they were placed into an innovative new unit called the ‘London Pals’.

Hugh was a courageous, lively, happy-go-lucky type, who quickly gained his first stripes. He was promoted to Lance Corporal with the East Surrey’s, and when he came home on leave, or wrote to Lionel and Daisy between battles, he always tried to play down the full horrors of life at the Front.

Lionel was just 5 years old when the First World War began, yet throughout his life, he was able to recall sitting on his father’s knee and listening intently to his tales of heroism. For Lionel, the trappings of war were far more exciting than mere toys, and he remained fascinated by Hugh’s campaign medals, his polished lapel and cap badges, uniform, helmet and rifle. For Daisy, however, the war marked the beginning of a long struggle to survive.

In addition to a new life in Australia, Hugh, Daisy and Lionel might also have enjoyed the security of a generous inheritance had not William James Crabb, Lionel’s paternal grandfather, suddenly died at the age of 45. William had become a wealthy corn merchant, adding generously to his own status and wealth when he married the beautiful Lavinia, the daughter of a prominent London merchant.

It seems that until William’s sudden death, the family lived in relative splendour, employing at least two servants. They resided at a number of exclusive addresses including a very fashionable detached town house, known as St Mary’s Lodge, on Lordship Road, Stoke Newington. Records describe this property as one of a number of ‘grand homes for gentlemen’.

William Crabb’s house was designed by one of the country’s leading architects of the time, John Young, and included rare arched windows and terracotta brickwork accents. In 1871, according to the deeds, 33-year-old William James Crabb moved into the property with his young wife Lavinia, their young daughter Lavinia Maud, aged three, and infant son Alfred Philips, who also became a well known architect. Hugh, Lionel Crabb’s father, was born six years later.

William’s unexpected death, twelve years after purchasing the property, affected the family business and it quickly fell into decline. His wife Lavinia died just five years later, leaving Hugh and his brother Alfred to the care of their 16-year-old sister, Lavinia Maud. Remarkably, she performed this task admirably well, and in 1901 she married Edward Henry Lovell, enjoying a well-to-do lifestyle, even employing two servants of her own.

Upon his sister’s marriage, Hugh Alexander Crabb was left to fend for himself. Having lost both parents by the time he was 12, and with money hard to find, he had to forfeit any hopes of further education by finding work. He was always interested in art and photography, and managed to obtain a job as a travelling salesman for a firm of photographic materials merchants. It is likely he met Daisy through her father, Jonas Taylor Goodall, who was also a salesman. Hugh’s occupation is listed as ‘commercial traveller’ in the 1901 census and the same title also appeared on his death certificate.

***

When Hugh Crabb was lost in the Great War, the boy’s ‘uncle’, Frank Jarvis, willingly and voluntarily took on a vital role to help with the young boy’s education and development. At 36, Frank was about four years younger than Hugh, and about the same age as Daisy. The pair had shared much of their childhood and were good friends. Frank had made his mark in the world of commerce some thirteen years earlier, in 1905, as a budding entrepreneur, when he and his business partner, Howard Garner, rented some temporary premises at 13 Paternoster Row, close to St Paul’s Cathedral in London.