Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

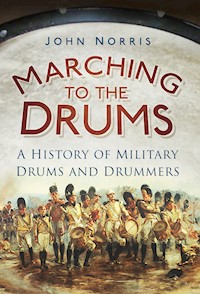

Military drummers have played a crucial role in warfare throughout history. Soldiers marched to battle to the sound of the drums and used the beat to regulate the loading and re-loading of their weapons during the battle. Drummers were also used to raise morale during the fight. This is the first work to chart the rise of drums in military use and how they came to be used on the battlefield as a means of signalling. This use was to last for almost 4,000 years when modern warfare with communications rendered them obsolete. Even so, drummers continued to serve in the armies of the world and performed many acts of heroism as the served as stretcher bearers to rescue the wounded from the battlefield. From ancient China, Egypt and the Mongol hordes of Genghis Khan the drum was used on the battlefield. The 12th century Crusaders helped re-introduce the drum to Europe and during the Napoleonic Wars of the 18th and 19th centuries the drum was to be heard resonating across Europe. Drummers had to flog their comrades and beat their drums on drill parade. Today they are ceremonial but this work tells how they had to face enemies across the battlefield with only their drum.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 386

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To my grand-daughter, Harriett Eleanor May, whose attempts at playing the drum made amusing diversions during the time spent writing this book.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Firstly I would like to express my gratitude to my wife Elizabeth, who waits patiently and takes notes while I take photographs and talk at length. My thanks go to the many re-enactment groups who have spared the time to speak to me on subjects relating to the use of the drum across the ages and also for allowing me to photograph them for this work. I thank the event organisers where the re-enactments displays are staged, particularly Gary Howard who arranges Military Odyssey. I am also grateful to the staff of regimental museums who have given their time so freely. I would like to thank Jesper Ericsson of the Gordon Highlanders Regimental Museum in Scotland for the images and some background detail on the return of the drums to the regiment. I am most grateful to Michael Cornwall at the Wardrobe Museum in Salisbury for allowing photography and giving me personal explanations of artefacts. My special thanks go to Dave Sands of the Worcestershire Regimental Museum for his support in providing additional material on the black drummers of the 29th Regiment of Foot and for providing illustrations used in the work; Dr Geoffrey Dexter with whom I discussed the use of human skin as drum skins and gave me an idea for the opinion I reached, and Barabara Birley, assistant curator at the Vindolanda Trust at Hexham, for answering the difficult question about Roman army drummers. My thanks go to Captain R.W.C. Matthews, Assistant Regimental Adjutant of the Coldstream Guards, for his time in answering my questions concerning drummer boys. I thank English Heritage and their staff at the sites in their care for making my visits very rewarding. Finally I would like to thank Grahame Gillmore for providing some excellent images, Chris Harmon who talked at length about drummers across the centuries, and the rest of the Diehards who portray the Victorian army with such high levels of authenticity.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Echoes from the Past

In the Beginning

The Spread of the Military Drum

Drummers in the Seventeenth Century

Marching and Drill

The Corps of Drums is Established

The Rise of the Regiments

The Napoleonic Period

After Napoleon

The American Civil War

Into a New Era

Drums Go to Sea

Drums in the World Wars

Regimental Customs and Battle Honours

Bibliography

Plates

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

As a young boy growing up on Jersey in the Channel Islands during the 1960s, I did many of the same things as some of my school friends, including joining the local Sea Cadet Corps. This organisation offered energetic lads the opportunity to go camping and sailing along with a range of other activities. There was also the corps of drums and as a member of this section of the organisation there came further opportunities such as travelling to England to participate in competitions with other units of Sea Cadets. We probably thought we were good and our long-suffering instructors, despite our undoubted awfulness, nevertheless encouraged us in our endeavours to produce a recognisable tune. Some lads played the bugle and for my part I tried the side drum. I remember thinking how heavy the thing was and how its large awkward size and shape made it unwieldy. Trying to march with the great weight slung over one’s shoulder, banging against the left leg, was virtually impossible and I soon asked to go on the cymbals because not only were they easier to play but they were also more manageable, being lighter and smaller.

Over forty years later, reflecting back on those boyhood days it seems incredible to think that there was a time when lads at the age we were in the Sea Cadet Corps had served as drummers in armies and marched into battle while beating out a rhythm to encourage the fighting men. It must have been a terrifying prospect going into battle unarmed and yet these young boys did not flinch. The names of most have long since been forgotten, or were never properly recorded, such as the little French drummer boy trapped inside the slaughterhouse that was Hougoumont Farm during the Battle of Waterloo in June 1815. However, some are still remembered, such as André Estienne from Cadenet, France, who was decorated by Napoleon and has numerous statues around France, and there is a handful known from the bloody episode of the American Civil War. As an historian such incidents involving individuals hold more fascination than they would for the passing curiosity of a tourist.

On coming to England after completing my education I joined the Grenadier Guards and once more found myself marching to the beat of drums. This time, however, it was as an infantryman taking part in ceremonies such as Trooping the Colour on Horse Guards Parade in London rather than as a musician. Such parades may seem like so much pomp and ceremony, but such pageantry served a purpose and is part of regimental history. Delving into the role of drums and drummers in military history, one comes to see them in a new and different light. These were brave boys and men who stood shoulder to shoulder with riflemen in battles all across Europe, North America, Africa and Russia. They had to pace out to set an example so that the army would advance and the casualty rate among drummers was extremely high. Even so, they did not flinch and continued about their duties regardless.

The drum is universally regarded as being the most basic of all musical instruments and its use can be traced across the continents from the earliest times and continues today with ceremonial occasions. Thousands of years ago the only way of communicating on the battlefield was by means of visual or verbal commands. Visual signals could be negated by bad weather or the line of sight being interrupted by obstacles such as woods or hills. Verbal commands were only useful for communicating at close quarters and could become ineffective over distance or drowned out by the noise of battle. Over time drums came to be used to relay signals and distinctive commands could be passed on by the echoing thumps on the drum. Brass instruments such as the bugle would eventually come to serve the same purpose as the drum, but that, as they say, is another chapter in military history altogether.

Over the centuries, drums have evolved to become symbols of inspiration, high morale and to signal victory. They have often been used to rally troops for one final effort rather than giving up. The Hussite leader Jan Ziska, 1378–1424, who campaigned in what is modern-day Bohemia and the Czech Republic, is understood to have ordered that his skin be used to cover the drums so that he may continue to lead his troops in battle after his death. Drums have also been used to signal the shame of an individual being thrown out of the army for actions which do not warrant imprisonment, but the perpetrator still had to be seen to be punished for the sake of discipline. Some drums have passed into legend, such as that taken by Sir Francis Drake on his voyages and which is believed to sound when England needs the assistance of the man who helped defeat the Spanish Armada in 1588.

Among the earliest militaristic societies to use the drum were the ancient Egyptians, who left reliefs carved in stone to depict campaigns in the region of the Sudan and Ethiopia showing drums deployed among the fighting men. For all its militarism the Roman army did not widely use drums, but relied instead on a range of other instruments including horns. It was not until the twelfth century that Europeans were once more exposed to drums when they encountered kettledrums used to relay signals among the ranks of the Saracen armies during the Crusades. Even the Janissaries (taken from the Turkish word yeniceri to mean new troops) as mercenaries in the Turkish armies made extensive use of drums for marching, morale, signalling and to intimidate their enemies.

The Janissary band was called the mehter and its commander was known by the title of Corbacibasi,who was dressed most resplendently, as befitted his rank, in fine attire which included brilliant red robes and a large white turban decorated with peacock feathers. This Turkish formation had a reputation for producing very loud music with trumpets and drums, some of which, the kettledrums in particular, were noted for their enormous size. Such formations accompanied the Turkish army on campaigns, including the war against Hungary in 1526 and in particular the Siege of Vienna in 1529 where it was said that 400 drums were pounding constantly. This would have been an early example of what we today call psychological warfare, designed to undermine morale and weaken resistance. One hundred years earlier, drums had been used at the conclusion of a prolonged siege when Jeanne d’Arc (Joan of Arc) made a triumphal entry into the French city of Orleans to the sound of trumpets and drums. She, in turn, was only continuing an example set by King Edward III of England who had entered the French city of Calais after the siege in 1347. Apparently Edward had used drums at the Battle of Halidon Hill, where he decisively defeated the Scots in 1333, and thirteen years later at the Battle of Crécy on 26 August 1346 drums were used in battle as the troops moved about the battlefield. The French-born chronicler Jean Froissart (known as John Froissart in English), 1337–1405, recorded in his works that at the Battle of Crécy the Genoese crossbowmen serving as mercenaries in the French army moved to take up their positions to engage the English army to the beat of drums. Turkish drums had long enjoyed great renown and it was the Swiss mercenaries of the time who spread their influence, the instruments referred to around 1471 as tambour des Perses (Drums of Persia) and included kettledrums.

Drums were also a distinguishing feature among the forces of the region referred to as the Middle East, continuing through the Ottoman Empire of Turkey and indeed becoming known as ‘Turkish Music’ when it was adopted by western armies in the sixteenth century. As tactics developed and armies increased in size, the role of the drum to beat out a rhythm to which troops could march as a single unit was established, and the drummer took on a new level of importance on the battlefield.

First used among the infantry units and then the cavalry regiments who adopted the kettledrum mounted on special harnesses fitted to its horses, these drums could be used to relay various signals. Drummers would be deployed to raise the alarm in the event of a sudden attack against a camp and rouse the troops to its defence, signal the order to attack or to retreat, and even call for an armistice to discuss terms to end the fighting. As the construction of drums became more advanced in design, so an increased range of notes could be beaten and the drum became incorporated into bands which included flutes, bugles and horns, leading to martial music which is recognised the world over as being the sound to which soldiers march whilst on parade.

Today, whenever a military band marches through a town, the sound of the drums beating invariably draws in people to watch the parade. It seems that some men never stop being boys and even veterans proudly stand as the band passes by.

In Britain the term ‘Drum’ is often to be found used either as part of or the whole name of public houses across the country and these can be found in towns such as Leyton in London and Doncaster in South Yorkshire. Drums and drummers have been immortalised in poem, song and story. Rudyard Kipling uses the theme of drums and drummers in the British army in several of his works, for example the two heroes in his short story The Drums of the Fore and Aft are young drummer boys. In his poem ‘Tommy’, Kipling’s words tell how the sound of drums can change peoples’ attitude towards the military when he writes:

Then it’s Tommy this, an’ Tommy that, an’ Tommy ow’s yer soul?

But it’s ‘Thin red line of ’eroes’ when the drums begin to roll,

The drums begin to roll, my boys, the drums begin to roll,

O it’s ‘Thin red line of ’eroes’, when the drums begin to roll.

There are many fine regiments in the British army which have an association with drums other than those used by drummers of the regiment. For example, the 2/34th Regiment of Foot (Later known as the Border Regiment) captured drums from the French 34th Infantry Regiment at the Battle of Arroyo dos Molinos on 28 October 1811 during the fighting of the Peninsular campaign. These were made regimental trophies and for its part in the battle the regiment was given the engagement as a battle honour, since which time the regiment has commemorated Arroyo Day with the captured drums proudly paraded as a reminder of the event.

Radios, telephones and computers may have replaced the drum as the means of signalling on the battlefield, but the history and tradition of the drum still remains part of the military culture, with beating retreat, drumhead tattoos, Trooping the Colour and a host of other parades. However, not all military parades involving drummers were convened for the purposes of military reviews. Drummers were used to administer punishment to those defaulters sentenced to flogging; a drummer would beat out the count of the lashes and a drum-major usually oversaw the punishment. At sea the Royal Marines would beat to quarters and on land drummers were to be found serving on campaign. All this was unknown to me as a young Sea Cadet such a long time ago, but now the time has come to tell the story of the drum and the drummer in war.

ECHOES FROM THE PAST

The battle had entered its third day and the troops on both sides were exhausted. All attempts by the French to cross the Alpone River at Arcola in Italy had been repulsed by strong Austrian resistance. The battle had started on 15 November 1796 and early assaults by the French to cross the wooden bridge spanning the river had been forced back with heavy losses. On the second day of the fighting the commander of the French forces in Italy, a young energetic general by the name of Napoleon Bonaparte, personally led one of the attacks across the bridge with flag in hand. This spirited attempt to force a passage was also repulsed, and it seemed as though an impasse had been reached. The Austrians’ superior firepower, including canister and grapeshot fired at close range from the artillery, was tearing into the ranks and inflicting a high rate of casualties on the French. The action had already cost the lives of nine generals and the French were facing defeat. Then on 17 November the seemingly impossible happened and some French troops managed to cross by swimming the freezing cold, swirling waters of the river with their weapons and equipment.

One of those crossing the river was a 19-year-old drummer boy by the name of André Estienne from the small town of Cadenet in the Luberon. He had managed to keep his drum dry by swimming with it perched on his head ‘…like an African native, carrying water in a pitcher…’ Having crossed over with infantrymen, André adjusted his equipment, gathered himself together and, according to the story, he began to beat his drum with such vigour and force that the Austrians believed they had been taken by surprise and were surrounded. Taking advantage of the diversion which distracted the attention of the Austrian forces, the French main force stormed the bridge and captured the town of Arcola (sometimes written as Arcole). The battle was won and the Austrians were in retreat.

André Estienne had joined his regiment in the Luberon and was engaged in the Wars of the French Revolution and attached to the Army of Italy under Napoleon Bonaparte at Nice, who rewarded the young boy for his valour by presenting him with silver tokens. Today, in memory of his bravery, a statue of André is to be seen in the square of his home town at Cadenet, where he is known as La Tambour d’Arcole (The Drummer of Arcole).

Some 4,500 years before young André exhibited his bravery in battle, the first military drums in history were entering service with the Egyptian army around 2,650BC, so beginning the story of the military drum which continues almost unbroken to this day. The country of Egypt falls into a region known as the Middle East, where over the centuries a number of military societies flourished, such as the Sumerians and the Parthians. Drums are among the oldest form of musical instrument and evidence of their existence goes back more than 8,000 years to around 6,000BC. Wall friezes and hieroglyphics dating from the period known as the Old Kingdom in Egypt, a timeline beginning from around 2,650BC to 2,152BC and encompassing the third to the sixth dynasties, have been discovered, although there are some authorities which also include the seventh dynasty, extending the timescale to 2,000BC.

In ancient Egyptian society, musical instruments were held in high regard and were of such importance that they are found in many paintings which decorate the interior of pyramids, often depicting deities such as Hather, Isis and Sekhmet engaged in playing a range of stringed instruments and even drums. These paintings are not just for decorative purposes; they tell a story which gives an insight into what was happening at that time. Through these images we can tell that drums were used in ancient Egypt and that the Pharaohs’ armies almost certainly used them on the march during campaigns into the Sudan and Ethiopia. Musical instruments were also an integral part of Egyptian religious services and images mainly show women engaged in playing these and possibly even creating a rhythm. There were several main types of instruments in ancient Egypt, all hand held, including items known as sistrums, types of rattles made from metal, crotals, which were made from wood and ‘slapped’ together, trumpets and, of course, drums, which fell into two forms.

The first of these forms was the barrel-shaped drum, which was probably used exclusively by the military units of the army. These players would have been experienced musicians and most images show these drums being played with bare hands thumping out the beat. Military musicians had to audition for the role of drummer to prove their capability and there is a record of one drummer proving his talent by performing 7,000 ‘lengths’ on a barrel-shaped drum. However, the account does not describe what actually constituted a ‘length’, but it is assumed to mean a rhythmical phrase to define drumming methods. No images have yet been discovered showing these drums being played using sticks, unlike for the round frame drum. The historian Lisa Manniche supports the theory that barrel-shaped drums were played by thumping with the hand because of the images showing them being played in such a fashion and because, as stated, no images showing them being struck using sticks have yet been found.

The round frame drum was also used in ancient Egypt and it is believed to have been developed around 1,400BC. Some examples have been found among grave goods at excavations during archaeological digs, along with painted and carved images which provide a picture to suggest these drums were played by female priestesses during religious ceremonies and other temple rituals. A drum was unearthed during excavations at Thebes in 1823 and this measured 18 inches (in) in height, with a diameter of 24in and was probably played using two sticks. In the book When the Drummers Were Women, the author Layne Redmond expands on this and, indeed, many images of the time do show women engaged in the act of drumming. Round frame drums are also understood to have sometimes been played aboard boats on the River Nile where they were used to set the timing for the oarsmen to row in unison. From this usage it was only a question of time before music, and drums in particular, particularly those bass-drum designs which have indefinite pitch, gradually came to find a wider role within the military and eventually onto the battlefield.

Drums are to be found in all societies across the continents of the world and come in all shapes and sizes. Drums are also one of the few musical instruments to be used for the specific martial purpose of signalling between military units on the battlefield and conveying a commander’s orders to whole armies, such as advance and withdraw. A Chinese military adviser around 500BC suggested that the drum be given ‘to the bold’, presumably because they would stand firm in battle. This was certainly the belief of Sun Tzu, the Chinese officer, philosopher and author of The Art of War in the fifth century BC. Sun Tzu is sometimes known as Sun Wu or Sun Zi depending on the pronunciation and his most important and influential work is also known as Bingfa. In this important treatise he states that: ‘Gongs and drums, banners and flags are employed to focus the attention of troops. When soldiers are united by signals, the bravest cannot advance alone, nor can the cowardly withdraw. This is the art of handling an army.’ This is perhaps the earliest recognition of the importance of the use of drums and flags on the battlefield for relaying signals, and recognises how flags can be used as rallying points for troops when reforming on the battlefield. Sun Tzu is also informing us that even in these early times troops had a loyalty to regimental symbols, either drums or regimental flags, and would not abandon them either by advancing without them or withdrawing and leaving them behind. In this work, not only do we see many strategic and tactical recommendations, but also the beginning of regimental customs which armies around the world would adopt over the centuries.

The Chinese military used a form of drum called the taigu, which was used to set the marching pace and also for signalling on the battlefield. An account of an un-named battle by an anonymous warrior from around this time tells how drums were beaten with sticks and signals were beaten out, which must have been fairly typical of how drums were used across the region before spreading further afield to influence other armies down to Korea and then into Japan.

Visual signals using hands and flags were an obvious and reliable means of communicating and of passing on orders to troops. This method of signalling can be traced back to around 3,000BC, but it did, however, require constant vigilance to watch for the next set of signal flags and in battle this is not always possible. Despite this drawback the armies of ancient Egypt used flags for signalling, as did the Roman legions with their vexillum standards, the Vikings with their raven banners, and the religious symbols and coats of arms of the Crusades.

The voice has a limited range and can easily become lost among the mêlée of screams and shouts during battle and so drums and horns or bugles were seen as a natural progression to relaying signals because their sound can be carried further. In large armies the drum worked well as a signalling device, but it has been opined that as armies grew larger it became more difficult to relay signals using drums. This may have been correct in some cases where the mass was not working as a truly cohesive unit. In the case of the Mongols where a tuman, or army of 10,000 and up to 100,000 men, worked as a co-ordinated force, the drum was successfully used to pass on signals. Admittedly, it helped greatly that the Mongols communicated their commander’s intentions down to the smallest group prior to engaging the enemy so that each man was aware of what he had to do. Even in later centuries when armies began to use gunpowder weapons, the drum was found to still have a place on the battlefield and drummers were present at Waterloo, the Crimean War and throughout the American Civil War, which were all fought at different periods in the nineteenth century.

All drums comprise an outer body or ‘shell’ formed into an open-ended tube, over which is stretched an animal skin which has been treated and prepared specially for use on the drum. The traditional material used for drumheads was always animal skin, usually calf’s leather, but today some plastics are used. There is a drawback to the use of natural animal skin, which is that rain or any other form of dampness can cause it to become slack, thereby affecting its sound, and so it has to be capable of being tightened. Conversely, if the skin becomes too dry it will split and the drum will be equally useless. The calfskin had to be prepared in a special process involving several stages of preparation to make it useful for drum coverings.

The method of preserving leather so that it does not decompose and can be used to make drum skins, belts, boots, gloves and other equipment, is called tanning. The process was known in South Asia perhaps as early as 7,000BC and the process spread so that by 2,500BC it was known to the Sumerians and the Egyptians. Ancient armies used leather for a variety of purposes, including the manufacture of armour and helmets for head protection, and the elastic properties leather possesses meant it made an excellent covering for drumheads.

The tanning process involved cleaning the skins and soaking them in special agents of tannin compounds in water to break down the natural protein structure so that it was no longer raw or untreated hide. It was a time-consuming process and many hundreds of people would have been employed in processing leather. Over time the demand for leather increased as harnesses and saddles for horses were required, and, as armies increased in size, so more leather was required for more equipment. This included skins for drums as more drummers had to be deployed with the larger armies if signalling was to be maintained.

Preparing leather was also an extremely pungent process, which at one time involved a vast quantity of human urine along with other noxious substances such as arsenic sulphide to remove the hair from the hides. It was a toxic mix and could produce madness, blindness or even both among those in the leather-working trade. Despite its obvious importance to the military societies, the production of leather was seen as a very demeaning task. Indeed, in some societies handling leather and human urine was completed by only the lowest of social castes. In 1047 a young 21-year-old Norman duke by the name of William besieged the castle at Alençon, lying on the Orne River in Lower Normandy, France. He was taunted in his efforts by the defenders who draped leather hides over the walls to remind the illegitimate duke that his mother had been a lowly tanner of leather. He was far from amused by the gesture and when he captured the site he ordered the mutilation of the thirty-two defenders by having their hands and feet chopped off and then thrown over the walls. The young duke is perhaps better known as William the Conqueror, who later defeated the English army of Harold at the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

The drum shell itself can be made from wood or metal and whilst pottery shells for drums do exist, the fragility of the material precludes it from being employed in military use where it would most likely break during the violent activity on a battlefield. Examples of drums made entirely of cast bronze have been discovered in China and these have been dated back to the Shang Dynasty of around 1,600 to 1,100BC. Archaeologists working at a location in East China have also recently excavated shards of porcelain at the site of a celadon pottery workshop dated to around 618 to 907AD during the Tang Dynasty in the region of Yugan County in the Jiangxi Province. These fragments have been pieced together and identified as the remains of porcelain waist drums, with a body length measuring some 16in and a diameter of 8in. The style is believed to have been popular and may have even influenced the design of drums in other regions. However, due to the fragile nature of their construction these drums must be ruled out as being intended for military use on the battlefield where the rigours would have led to them becoming damaged or broken. It must therefore be concluded that such drums were intended purely for either ceremonial or parade use, possibly to celebrate military victories. Pottery drum shells from an earlier period have also been discovered at an archaeological excavation at a site near Taosi, close to the Yellow River. These have been dated to around 2,000BC, possibly during the Zia Dynasty, and some show signs of having been decorated with red colouring which traditionally was used as a symbol of a ruler’s power. Some Chinese drums were made in one piece using a hollowed-out tree trunk and some of these may have measured as much as 3ft in height and may have been the types used by the military. The German writer J. Schreyer noted as early as 1681 how some tribes in Africa: ‘… take a [clay] pot and bind a skin over it, and on this pot the women beat with their hands and fingers for these are their drums (trummeln) and kettledrums (paucken)’. This is an example of how different cultures, despite being separated by thousands of miles, evolved along similar lines and here in this scene the observer is recording women beating drums as in the Egyptian society of some 3,000 years earlier and also using pottery shells in the same way which we now know were used to form drums in China. In the Middle East similar clay drum shells have been discovered and it is believed these may have been covered with a drum skin of either donkey or goat stretched over the end. Some examples of wooden drum shells have also been found and these would have been covered in animal skins for the drumheads.

One of the earliest types of drum is that form known as ‘frame’, which has a body or shell with a shallow depth and has a diameter greater than its depth. It is a very old form of design, the drum skin being attached firmly to the wooden shell, which prevents the tension from being adjusted to alter the pitch. The circular shape of the shell is formed by a single piece of wood bent round, with the two ends joined together using a scarf joint cut at a very sharp angle to allow the ends to be fixed together using glue or nails. Examples have been discovered in various cultures from Europe to Asia and accorded different terms such as daffu or kanjira in India, bodran in Ireland and daf in some Middle Eastern countries. In Brazil it is called the tamborim and in Europe, where metal discs are attached to the frame, it is known as the tambourine. This evolved differently from the drum used by the military, and frame drums were more likely to be used for parades or festivals as opposed to being used for signalling on the battlefield.

At first it may have been that the banging of a drum was used to attract the attention of the troops, or at least unit commanders, and cause them to look at the flags which were the more traditional means of signalling on the battlefield. Over time, forms of communication combined with flags and drums were placed together in some military societies, later to be joined by trumpets. This combination of drums and flags to relay orders continued into the nineteenth century and each developed its own unique set of patterns for orders. Flags developed into a method known as semaphore signalling and drums developed ‘rolls’ as signals. It was a method which worked extremely well and control could be exercised over single, small units or larger formations with a number of drummers being dispersed through the army.

IN THE BEGINNING

The Roman military society, for all its innovations and quickness to grasp the importance of advances, was one of those few establishments which did not make use of drums and preferred instead to rely on wind instruments such as the tuba or cornu. The Roman philosopher Boethius believed ‘… music is part of us, and either ennobles or degrades our behaviour’. The poet Juvenal thought that ‘… of all the noises, I think music is the least disagreeable’. The Romans would almost certainly have been familiar with drums through contact with Egyptian religious ceremonies and with its military. Because of this, it has been opined that some units of the Roman army may have been inspired to use drums in an unofficial capacity. However, despite this theory the Roman army never used drums either to signal or as an aid to keeping step on the march. Staff at the ongoing archaeological excavation at the Roman frontier fort of Vindolanda in Northumberland confirm that they have never uncovered any positive evidence to show the Roman army used drums. A number of other highly respected research groups on Roman military equipment, including the world-famous Ermine Street Guard, also confirm that there is no evidence to support the suggestion that the Roman army ever used drums. The Romans were not alone in this negative opinion of drums and most of the earlier Greek City States did not use drums either, but rather opted for the more gentle sound of flutes to accompany their troops when going into battle. When the Roman Empire began to contract and leave Europe in the early fifth century AD, it left behind a vacuum which was filled by various local tribal leaders, some more war-like than others, along with a wealth of technology and other skills. Some of these Roman influences fell into disuse over time while others were maintained, such as styles of weaponry, but as drums had never been a part of the Roman army they were not found in post-Roman Europe.

The drum is one of the most basic designs of all musical instruments and because of its simplicity it was easy for different cultures to replicate examples they had come into contact with and develop their own style. The drum by its very nature is tubular in construction and varies in depth to control its resonance when being beaten by hand or struck with a stick. Some drum designs, such as those from India and China, have a barrel-like shape while some are goblet-shaped, which usually tend to only have one membrane covering and generally originate from the Middle East and are known as durabuka. The wooden shell of a drum is not overly complicated to produce and so is common even among primitive societies. Attaching the membrane to the shell using small nails, pegs, glue or even a binding would not be beyond the capability of such societies which would have been using similar techniques to attach spearheads to wooden shafts for the purpose of hunting or for warfare in the more militaristic groups. Some drum designs were developed with twine attached to the membranes, referred to as the ‘lacing’, and is common on double-headed drums and used as a means of allowing more tension to be exerted on the membranes to adjust the sound. This lacing could take the form known as ‘W’ or ‘Y’ style from the pattern it formed. Throughout the centuries, drums have been used in many rituals, from religious ceremonies to royal precessions. In Africa, for example, drums have been used to fulfil duties in both roles. In Europe the drum was absent for many years until it was gradually re-introduced over time, becoming increasingly widespread during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Sometimes being called tabour or timpani, these drums were reserved for special occasions and used mainly in rituals involving pageantry of royalty.

The drum, very early on in its development, came to be used as a form of communicating messages over considerable distances using a range of coded signals. All drums, including the Indian bayan and the Japanese tsuzumi,are classified as membranophones, which is to say the sound they emit is created when the membrane covering of the shell is struck either by hand or with a stick so as to cause it to vibrate. It is a simple yet effective means of creating distinctive sound patterns and evidence of drums can be found all over the world. The Japanese historical chronicle Gunji Yoshu records how the form of a drum known as a taiko was used to beat out signals to summon allies to battle and how the taiko yaku (drummer) set the pace of marching, usually around six paces to the beat. The taiko drum is believed to have originated in China some time during the Yayoi period (500BC to 300AD) where it also had a martial use as a signalling device on the battlefield. Today, taiko drums are used during special ceremonies and have even developed into an art form for public entertainment with performances being given at concerts. Drummers in ancient India, for example, used a range of strokes of the hand to beat a rhythm using a drum such as the tabla. Other drums in use in India included the dholak, which could be tuned by adjusting the tension of the strings attaching the skin to the body, usually by means of a wooden peg, and this either slackened off or tightened the skin to alter the pitch. The bayan or doogi was another drum developed in India and this was similar in style to a drum used in Egypt, being played in a like fashion, using only the hands. A range of other types of drum were developed and used in India including the dhol, chenda and dhimay. In seventh-century India, Hindu armies used drums to rouse the troops from their sleep and a range of signals also alerted them to the distance they had to march that day. The author of the Kalingattu Parani (a poem about the victory of the Chola King in around 1,000BC)records how a Hindu army on the march was most impressive with: ‘… conch-shells sounded, the big drums thundered, and the reeds and pipes squeaked till the ears of the elephants… were deafened…’ There are many Indian records containing accounts of battles which tell how drums were used to inspire the troops whilst trying to unsettle the enemy. In Thailand, drums were beaten to herald the approach of victorious armies, often led in procession by war elephants. To train elephants for warfare they were subjected to the sound of drums being beaten to make them used to such noises on the battlefield. Indian armies also used camels to carry drums for use on the battlefield and there are some illustrations which show them being used in such a role.

In South America, excavations of archaeological sites have revealed evidence of the use of drums in Aztec, Mayan and Incan cultures, which were particularly militaristic societies. Carvings in stone reliefs show drums being used by these civilisations, but to what extent and whether they were used widely as forms of signalling on the battlefield is not yet entirely clear. Such evidence is important in understanding the use of drums within the society as a whole, in exactly the same way as the Egyptian tomb paintings discovered in the pyramids. It is known that the Aztec military in what is modern-day Mexico used a type of drum called the tlalpanhuehuetl. The drum was wooden and stood over 3ft in height, with the drumhead made of jaguar skin and decorated with images of birds and other animals. The Incas who lived in what is modern-day Peru and Chile are also known to have beat war drums when going into battle. Similarly, in the North American continent the Native American tribes also used drums for ceremonial purposes, to intimidate enemy tribes and as signals. These were crudely made but functional devices and when white European settlers colonised the lands these native tribes utilised discarded items such as wooden barrels, covering them with hides and fashioning them into extemporised drums.

It would appear that, for whatever reason, drums either fell out of use in the European military societies or had never been considered of any real relevance and therefore were not included in the structure of a military unit. Drums would almost certainly have been known about, but even in the eleventh century they do not appear as part of the European military system and there is no imagery of them in the Bayeaux Tapestry which records in considerable detail the Norman Conquest of Britain in 1066. It would not be until the Crusades were undertaken, which were a series of religious expeditionary wars conducted between 1096 and 1291, that the European armies found themselves exposed to the effects of the drum, which was an important object in the structure of the Muslim military forces. This is an opinion supported by the historian David Nicolle, who writes that: ‘The increasing importance of military drums similarly almost certainly reflected Islamic musical influence via the Crusades, Sicily and Spain.’ As a result, a number of other instruments were introduced into European culture and the drums in particular had their names treated to European translations, so that the tablah became the tabor and the naqqarah became the small naker.

We learn of Crusaders coming into contact with drums from the writings of leading figures such as Jean de Joinville, who fought at the Battle of Mansourah (sometimes written as Mansura) on 8 February 1250 during the Seventh Crusade (1248–1254). A force of French knights attempted to capture the town, but upon entering it the Muslim forces proceeded to cut them to pieces. Jean de Joinville, who was badly wounded in the fight, later wrote: ‘As I stood there on foot with my knights, wounded as I have told you, King Louis came up at the head of his battalions, with a great sound of shouting, trumpets and kettledrums’. The attack continued and de Joinville wrote of the battle’s progress how: ‘As the [French] royal army began to move there was once again a great sound of trumpets, kettledrums and Saracen horns’. From this eyewitness account it would appear that drums were beginning to enter into use with European Crusader forces by the early to middle period of the thirteenth century. The European Crusaders, as we see here, used trumpets and adopted drums to use for signalling purposes, even using them to signal between vessels sailing in convoy. The order of the Knights Templar from this period are also known to have used bells to awaken the soldiers and to sound the alarm in the event of them being attacked. These would not have been small, delicate devices but rather large, clanging versions which would have echoed around the walls of a building, leaving no-one in any doubt that an alarm was being rung.

The term we use today to describe the area of the Middle East is a relatively modern expression and encompasses the region lying between longitude 24° and 60° east, taking in Asiatic Turkey, Iraq, Iran and several other states in the area. Over the centuries, many military societies came to flourish in this region and many great campaigns were fought here, including Megiddo, which is one of the earliest recorded battles from around 1,468BC. One of the most prominent military societies from the mid-thirteenth century was the Mamelukes; professional Islamic soldiers, usually of slave origins, who placed great value on bands of musicians. At one point the sultan is known to have had forty-four drums, four hautbois (oboes) and twenty trumpets grouped as a band. It was considered a great honour to be allowed to have a band and those amirs who were granted permission were given the title of ‘Lords of the Drums’. It is believed that about thirty such amirs were to be given the honour of having a band and each would have had command of forty horsemen, with a band of ten drums, two hautbois and four trumpets. To be granted permission for a band was an elite status symbol for amirs, who would usually serve as Islamic officers, whilst others may have held office as frontier governors. The drums in such cases were more than just a statement of rank as they had a specific role in battle, being used to undermine an enemy’s confidence and hopefully cause chaos in the ranks of an opposing army, particularly among the horses which would have been unaccustomed to such sustained noise. The Muslim horses on the other hand would have been quite used to the sound of the drums, probably being introduced to the rhythmic pounding as part of the training for warfare.

The noise produced by a drum is a short but continuous sound, which can be achieved by striking the drumhead rapidly. The side drum creates a very short sound and cannot be beaten fast enough to produce what seems like a continuous sound, and so the distinctive ‘rat-a-tat-tat’ is produced. With the bass drum the drummer can strike alternatively to produce the effect of a continuous sound. The rhythm to achieve this effect has to be practised because if struck too quickly the drummer’s action will negate the effect of the vibration of the preceding stroke. The same principle applies to kettledrums or nakers