Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Mercier Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

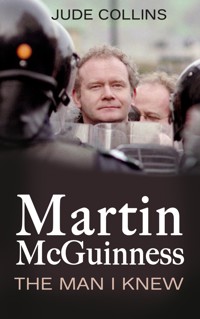

In Martin McGuinness, The Man I Knew, Jude Collins offers the reader a range of perspectives on a man who helped shape Ireland's recent history. Those who knew Martin McGuinness during his life talk frankly about him, what he did and said, what sort of man he was. Eileen Paisley speaks of the influence she believes her husband, Ian, had on him; former Assistant Chief Constable Peter Sheridan recounts how the Derry IRA targeted him as a Catholic RUC policeman; peace talks chairman Senator George Mitchell comments on the role he played in talks that led to the Good Friday Agreement; and Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams remembers the man who for so many years was his closest colleague. Other contributors include; Ulster Unionist MLA Michael McGimpsey, prominent Irish-American Niall O'Dowd, peace talks chairman Senator George Mitchell, 54th Comptroller of the State of New York Thomas P. Di Napoli and Presbyterian minister David Lattimer.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 528

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To the memory of my much-loved sister,

Patricia Friel, and my brother, Fr Paddy.

MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

www.mercierpress.ie

www.twitter.com/IrishPublisher

www.facebook.com/mercier.press

© Jude Collins, 2018

ISBN: 978 1 78117 601 6

Epub ISBN: 978 1 78117 602 3

Mobi ISBN: 978 1 78117 603 0

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

List of Contributors

Gerry Adams was president of Sinn Féin from 1983 to 2018 and has been teachta dála (TD) for Louthsince 2011. From 1983 to 1992 and from 1997 to 2011 he was member of parliament (MP) for West Belfast. During his time as president, Sinn Féin became the third-largest political party in the Republic of Ireland, the second-largest in Northern Ireland and the largest nationalist party in Ireland.

Dermot Ahern is a former Irish TD for the Louth constituency. He was chairman of the British–Irish Inter-Parliamentary Body from 1993 to 1997, minister for foreign affairs from 2004 to 2008 and minister for justice, equality and law reform from 2008 to 2011. Since his retirement from politics in 2011, he has become an accredited mediator and uses his experience and contacts to work in the area of alternative dispute resolution.

Martina Anderson is a former political prisoner and a Sinn Féin politician. She was a member of the legislative assembly (MLA) from 2007 to 2012, and served as a junior minister in the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister from 2011 to 2012. She has been a member of the European Parliament (MEP) from 2012 to the present.

Denis Bradley was educated at St Columb’s College, Derry and later studied in Rome. He served as a priest in the Bogside and was a twenty-six-year-old curate on Bloody Sunday. He left the priesthood later in the 1970s. He was a founding member of Northlands alcohol and drugs residential counselling centre in 1973 in Derry and remains involved with the work of the centre as a consultant. Denis is also a consultant to the North West Alcohol Forum in Co. Donegal. He was vice-chairman of the Northern Ireland Policing Board from its formation on 4 November 2001 to 2006. In 2007 he was appointed co-chairman, along with Rev. Robin Eames, of the Consultative Group on the Past in Northern Ireland. A well-known political commentator, Denis also writes a monthly column for the Irish News and received an honorary doctorate of law from the University of Ulster for his contributions to the community and the peace process.

Bill Clinton served as the forty-second president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. Prior to the presidency, he was governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and again from 1983 to 1992.

Thomas P. DiNapoli is the fifty-fourth comptroller of the state of New York. He has served in this position since 2007. One of his primary responsibilities is to oversee the New York state pension fund – the third largest public pension fund in the United States, which provides retirement security to over a million public workers and pensioners. Under his leadership, the fund has invested nearly $270 million in Irish companies and made $30 million in private equity commitments specifically targeted at Northern Ireland. His office also examines how American companies are implementing the MacBride Principles legislation and where these companies invest their capital in Northern Ireland.

Pat Doherty is director of corporate governance in the Office of the New York State Comptroller, where he helps develop and administer social and environmental responsibility initiatives for the $184 billion New York state investment fund. Before coming to the state comptroller’s office in 2010, Pat was director of corporate social responsibility in the Office of the New York City Comptroller.

Peter King, a member of the Republican Party, is serving his thirteenth term in the US House of Representatives. He is a member of the Homeland Security Committee and also serves on the Financial Services Committee and Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. He served as chairman of the Homeland Security Committee from 2005 to 2006 and again from 2011 to 2012. He has been a leader in homeland security and is a strong supporter of the war against international terrorism, both at home and abroad.

David Latimer grew up in Dromore, Co. Down. Before becoming a Presbyterian minister, he worked as a systems analyst with Northern Ireland Electricity. In 1988 he was appointed minister of First Derry and Monreagh Presbyterian churches. During 2008 he served as a hospital chaplain in Afghanistan. David is married to Margaret and has three daughters.

Aodhán Mac an tSaoir is from a strongly republican family. In 1971, as the conflict deepened, he joined the republican struggle and has been a full-time political activist for most of his life since then. From 1992 he worked as political adviser to Martin McGuinness and was a close friend.

Eamonn MacDermott worked in the film business and was involved in making a documentary about Johnny Walker of the Birmingham Six, among other projects. He was also a reporter with the Derry Journal for many years. He subsequently was editor of the Sunday Journal before leaving to go freelance in 2009. He is a former republican prisoner, having served almost sixteen years in the H Blocks.

Martin Mansergh is a former Fianna Fáil adviser and politician, and a historian. He was a member of the Irish Senate from 2002 to 2007 and TD for Tipperary South from 2007 to 2011. He played a leading role in formulating Fianna Fáil policy on Northern Ireland.

Pat McArt was editor of the Derry Journal from 1982 to 2006. During those years he had almost daily contact with local leaders such as John Hume, Martin McGuinness and Bishop Edward Daly. He began his career in his hometown of Letterkenny, Co. Donegal, before moving to RTÉ in Dublin in 1980. He has frequently broadcast on both national and local media.

John McCallister was born and grew up on a family farm in Glasker near Rathfriland, Co. Down. He was president of the Young Farmers’ Clubs of Ulster from 2003 to 2005 and MLA for South Down from 2007 to 2016. He was the first MLA to pass a private members bill (PMB), the Caravans Act of 2011, and the only member to have a second PMB passed, the Assembly and Executive Reform (Assembly Opposition) Act 2016. An Ulster Unionist Party member from 2005 to 2013, he resigned over an electoral pact in a Mid-Ulster by-election. Co-founder of political party NI21 in June 2013, he resigned in July 2014. He is currently the Northern Ireland human rights commissioner.

Eamonn McCann is a long-time socialist and member of Derry Trades Union Council. He is involved in campaigns for workers’ rights and women’s liberation, and against state repression and defilement of the environment. ‘If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be part of your revolution’ is his favourite quotation, which was first uttered by political activist and writer Emma Goldman.

Mary Lou McDonald is a Dubliner, mother and unrepentant Fenian. In 2004 she became Sinn Féin’s first MEP and is currently TD for Dublin Central. She was deputy leader of Sinn Féin from 2011 and became its president in 2018.

Michael McGimpsey is a former Ulster Unionist Belfast city councillor and MLA in the Stormont Assembly. He worked closely with David Trimble and was made minister for the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure, and later minister for health in the Stormont Executive.

Mitchel McLaughlin was a lifelong friend and confidant of the late Martin McGuinness. Until he retired from day-to-day politics, he was a leading strategist and spokesperson for Sinn Féin over a forty-year period. In public life he served as Sinn Féin’s national and regional chairperson, local councillor, MLA and speaker of the Assembly. Mitchel also played a key role in developing the peace process, engagement with the unionist community and in the development of Sinn Féin’s economic policies.

Joe McVeigh was born in Ederney, Co. Fermanagh in 1945. He attended Moneyvriece Primary School, St Michael’s Grammar School, Enniskillen and St Patrick’s College, Maynooth. He was ordained for the diocese of Clogher in 1971 and has served in parishes in Monaghan and Fermanagh. He is assistant priest in St Michael’s parish, Enniskillen. His hobbies are music and reading.

George Mitchell served for several years as chairman of the global law firm DLA Piper. Before that, he served as a federal judge; as majority leader of the United States Senate; as chairman of peace negotiations in Northern Ireland, which resulted in an agreement that ended an historic conflict; and most recently as US special envoy to the Middle East. In 2008 Time magazine described him as one of the 100 most influential people in the world. Senator Mitchell is the author of five books. His most recent are a memoir entitled The Negotiator: Reflections on an American Life (2015) and A Path to Peace (2016).

Danny Morrison is a writer and media commentator. He is the author of seven books, including novels, non-fiction, memoir and political commentary, as well as several plays and short stories. Formerly, he was the national spokesperson for Sinn Féin, editor of An Phoblacht/Republican News and MLA for Mid-Ulster. He was imprisoned several times between 1972 and 1995.

Niall O’Dowd went to America in 1979 from Drogheda, Co. Louth. He is the founder of IrishCentral.com, Irish America magazine and the Irish Voice newspaper. He was awarded an honorary degree from UCD and an Irish Presidential Distinguished Service Award for his work on the Irish peace process.

Terry O’Sullivan, general president of the Laborers’ International Union of North America (LIUNA), is a proud descendant of Irish immigrants, holds dual American and Irish citizenship, and works tirelessly to build bridges between the Irish and American labour movements. He is a vocal supporter of Sinn Féin and serves as president of New York Friends of Ireland and chairman of DC Friends of Ireland.

Eileen Paisley, Lady Bannside, Baroness Paisley of St George’s, is the widow of Ian Paisley, former leader of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). She became a life peer in 2006.

Jonathan Powell is director of Inter Mediate, the charity he founded in 2011 to work on conflict resolution around the world. He was chief of staff to Tony Blair from 1995 to 2007, and from 1997 to 2007 was also chief British negotiator on Northern Ireland. He is author of Great Hatred, Little Room: Making Peace in Northern Ireland; The New Machiavelli: How to Wield Power in the Modern World and Talking to Terrorists: How to End Armed Conflicts.

Dawn Purvis was a former leader of the Progressive Unionist Party (PUP) and MLA for East Belfast. Dawn left politics in 2011 and worked with Marie Stopes International to open the first sexual and reproductive health centre offering abortion services on the island of Ireland. Dawn is currently CEO of a housing charity.

Peter Sheridan OBE is a former assistant chief constable of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and of the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI). He is currently chief executive of Co-operation Ireland.

James T. Walsh is a government affairs counsellor in the Washington DC office of K&L Gates LLP. He served in the US House of Representatives from 1989 to 2009 and during his tenure was a deputy Republican whip from 1994 to 2006. He was a member of the House Committee on Appropriations from 1993 to 2009 and became chairman of four House Appropriation subcommittees: District of Columbia; Legislative Branch; VA, HUD and Independent Agencies (NASA, EPA, FEMA, NSF, Selective Service); and Military Quality of Life (which included jurisdiction for Military Base Construction, the Defense Health Program and Housing Accounts) and Veterans Affairs.

Foreword

I first considered writing a book about Martin McGuinness some years ago. We’d met on a number of occasions, including the 2010 launch of my book Tales Out of School: St Columb’s College Derry in the 1950s, where he was a guest of honour. But a series of obstacles and distractions intervened and as Martin himself said of his intention to retire from the position of deputy first minister in May 2017, ‘The best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry.’

His sudden illness and death in March 2017 shocked everyone. Much was written at the time about this youth from the Bogside who became an Irish Republican Army (IRA) leader, a forceful politician and finally deputy first minister of Northern Ireland. What was lacking, in my view, was the direct testimony of people who had met and interacted with him at different points in his life.

In Martin McGuinness: The Man I Knew, I have tried to bring together as wide a range of voices as possible: from those who knew him as a neighbour and an IRA leader, to those who worked with him in the Stormont Executive; from Gerry Adams and Mary Lou McDonald to Eileen Paisley and former Ulster Unionist MLA Michael McGimpsey; from prominent Irish-American Niall O’Dowd to peace talks chairman Senator George Mitchell. If I have a regret, it is that I have not been able to include more voices from political unionism.

The focus of all the interviews is Martin McGuinness, but inevitably contributors range beyond the subject, commenting on the turbulent social and political circumstances in which he lived. What I first thought of as digression, in fact provides a background and context for the life of the late deputy first minister. And of course contributors, in telling us about Martin McGuinness, tell as much about themselves. I’d like to thank them all, on both sides of the Atlantic, for giving so generously of their time. I am also indebted to those who facilitated the interviews.

No book can tell the full story of a person’s life. The modest ambition of this volume is to offer the reader a range of perspectives on a man who helped shape recent history and whose death has left Irish politics poorer.

1

Mitchel McLaughlin

Martin and I played on the same soccer team when we were young. At that time he was nine or ten. He was a passable goalkeeper – he wasn’t quick on his feet, but he was a big cub for his age and there was never any doubt that he’d be the goalkeeper; it seemed to be his natural position. He also had very quick hands so he was a decent schoolboy keeper. That was soccer, although we played Gaelic football too. Mind you, back then you couldn’t admit you played both. But he wasn’t somebody I’d be meeting coming from school every day, although we’d parallel paths. If there was a football game you’d have known to look out for him.

In the early 1970s we became reacquainted. At that stage he was already a considerable figure in the republican movement. The thing to remember is that, although it didn’t have the depth or breadth of counties like Tyrone, Armagh, Antrim and Down, where the republicans could trace their ancestors back to the United Irishmen and 1798, Derry did have a republican tradition. It was Catholic and nationalist. My father’s family were serious supporters of the old Nationalist Party. On my mother’s side, my maternal grandmother was a member of Cumann na mBan at the time of the 1916 Rising.

Growing up, we lived in a nationalist environment where the injustices of gerrymandering and unionist control of the council were being badly felt – so radical politics, such as those espoused by the Derry Housing Association, were of interest to us. In the early days Martin was already involved in the civil rights marches. He was energised by the whole campaign against gerrymandering and discrimination. If the state hadn’t reacted the way it did, he’d probably have gone on being a van driver and working for Doherty’s butchers. Instead, he got drawn into it with a whole lot of other people, a new fraternity who were developing their politics. They were not revolutionaries waiting to strike: they started from a very low base. But from all of that, he emerged as a significant player and came to the attention of the national leadership.

Martin and I became involved separately in supporting the protests against discrimination. That was 1967–68 – running up to the first civil rights march. I was on the march on 5 October 1968, opposing unionist gerrymandering and discrimination – I don’t think Martin was there. But it was the beginning of a political journey that would bring us closer together. Neither he nor I was particularly vocal then – the radical and strident voices were the Eamonn McCanns of the day [a radical young socialist agitator in Derry]. If there was a platform, you would have had business people, clergy, Eddie McAteer [leader of the Nationalist Party], John Hume – the emerging professional people – taking to the stage. We were more the foot soldiers of the day for people who didn’t see this as a militant process. But I think our instincts were that it could be.

I was listening to all the messages about Martin Luther King and so on – but their impact didn’t last too long. People talk nostalgically of the changes that came about through non-violent agitation for civil rights in other countries, including the US. But what really made an impression on me was what happened on 5 October [when the RUC attacked civil rights marchers] and the reaction to it. I don’t remember Martin’s reaction to it and I never discussed it with him.

My first proper conversation with Martin coincided with the Free Derry period. There was the division between those just cutting their political teeth and the older, establishment people, who had a completely different view of what would happen. And it was a confused situation. Not only were there barricades round the area, but there were armed people driving around in cars they’d hijacked – they always seemed to be Ford Cortinas. So there was a meeting in Free Derry, which I think had mainly to do with antisocial issues and the tensions that had emerged between the Official IRA and the Provos. The meeting was held in a community hall, an old wooden structure. And there were maybe sixty, seventy people at it.

At the meeting you had all these young insurrectionists – a different generation – who were questioning how antisocial elements should be dealt with; in other words law and order in Free Derry. Martin was on the same side of the discussion as I was [arguing for sanctions other than kneecapping to be used in dealing with antisocial elements].

At this point the army was on the streets, the IRA was on the streets, Bloody Sunday had come and gone. And this was a time when people with authority emerged – Martin was one of those. He spoke with the authority of the republican movement – that was very clear.

The next time I remember Martin being part of a discussion I was involved in was about the monument that had become Free Derry Corner. Free Derry Corner at that point was a derelict terrace of houses where Caker Casey – a local character of fame and renown – had painted ‘You are now entering Free Derry’ on the gable wall. There were proposals in place to knock it down because a road, a fly-over, was going to be built – something that I suspect the security forces would have had a big say in.

Martin could turn the heat up in meetings such as this. His normal tone was the flat, unemotional line in response to arguments that people were putting forward. But whenever there was a persistence not to his liking, say with the Free Derry Corner, Martin just cut to the chase and said, ‘Look, everything’s up for discussion except the removal of that wall.’ Calmly put, but the end of the debate.

A British sapper, who is said to have hijacked his vehicle, drove into the Bogside and crashed into the wall of Free Derry Corner, destroying part of it. The reaction was to build it again, stronger, with buttresses – the road was eventually built round it. It was originally a handy gable wall for putting up the message; it later became a symbol of what could be. When the wall was rebuilt, it was repainted and the lettering of ‘You are now entering Free Derry’ was reinstated as well, only this time it was done neatly. Eamonn McCann had a strange reaction to all this. He lamented that we had institutionalised Free Derry Corner.

Following on from this, Martin in particular became very conscious of the fact that the barricades in the area were not only symbolic. They were in fact a barrier to those going out and coming in, and sometimes you were putting limitations on people who were maybe involved in IRA activity – there were only a limited number of ways you could get back into the area. So at one meeting Martin argued that the barricades should be taken away – and that was against popular opinion in the Bogside then. He said, ‘Do you really think those barricades would stop the British Army from coming in here?’ So they took the barricades away and they painted a white line round Free Derry – and the British Army agreed not to cross over this white line! Martin felt the barricades were a complete waste of time and energy, and gave a false sense of security. And that was where I began to see his leadership capacity.

Martin stood out in any grouping. You saw the press conferences and the delegations sent over to London to negotiate with the British government and he was part of the IRA leadership. In Derry he was already recognised as the go-to person. And he was on the run – the British knew about him, the same as everybody else. But the Free Derry area was one where the British Army couldn’t come in and be undetected for very long. So he wasn’t skulking about – he didn’t have to – nor did any of the IRA volunteers when within Free Derry, the Bogside or the Creggan. He couldn’t have gone into the centre of town though.

The British knew he was there. There were many instances of them coming in, usually in the dead of night. There was a community alarm system – bin-lids – and that meant that people were mobilised very quickly, though a number of people were killed. The British had that ability, always had.

Martin stayed in different houses. He wasn’t going to his own house and he wasn’t going to the same billet every night. He just had to assume there was surveillance of some kind – as well as informers.

***

Derry at the time was re-establishing a republicanism that had been very reduced. The growth of republicanism there was far greater in proportion to anywhere else because of the standing start. In Belfast they had the expectation – we didn’t have that in Derry, there was only a handful of people. But not only was it reassembled, it became a formidable operation in the city. The bombing campaign which characterised the IRA campaign during the 1970s was particularly prominent there. Yet Martin McGuinness was one of the first I heard saying, ‘This bombing campaign has its limitations. Do we really think that’s going to force the British to negotiate or to withdraw from Ireland?’ He had a very tight grip on the types of bombing operations that were permitted.

I’m quite sure there were tensions among republicans. Some were of my father’s generation, and some beyond that. So they weren’t all about to pick up the gun and go out, although some did. But they weren’t resentful of a younger generation coming along, with new leadership emerging. This was a new type of struggle. Martin and his cohorts from that generation were largely unknown at the start, but they gradually became known.

There is a lot of fairly crass speculation as to what Martin’s military capability was. I’ve read that he was a crack marksman. Well, I know that he had weak eyesight. It was his leadership, his judgement, his authority that got people locally to accept his leadership and to do it with great loyalty and commitment to him. You saw the turnout there was for his funeral – how that loyalty to him had permeated public opinion on the island. Nobody was basing his authority on the grounds that he was a crack marksman.

He had an ability to carry his own natural personality with him. Mostly he was the warm Martin McGuinness. But an issue emerged if you tried to pressurise him, if you tried to bully him or threaten him; then the other side – a fearless, indomitable aspect of him – emerged.

I’ve seen that come out. Here’s an example. There was a raid on a house not far from here. Both he and I turned up at it. It was the RUC. This would have been the mid-1980s, when we both had a public profile. So we got the call that somebody was being raided and we went round to a situation that quickly became quite nasty. There was a very well-known Special Branch officer and it was his brother who was leading this raid. I think they were from Omagh. What emerged was, basically, some sort of sectarian remark that both Martin and I reacted to. After that things got quickly out of hand. Martin ended up grabbing this sergeant by his tie through the railings in the staircase in this house. There were about four or five RUC men trying to pull him off. The harder they pulled the tighter he held onto the tie – it was strangling the cop. It was hilarious in retrospect, but at the time it was hairy – I thought he was going to kill the sergeant, just by holding onto his tie.

A side issue of this: after the incident my wife, Mary Lou, used to see that cop down the town, and she would be making strangling motions at him every time. He eventually disappeared – he was involved in some civil prosecution. So Mary Lou broke him!

But that was the side of Martin McGuinness you rarely saw. I don’t think it was reckless. It was the way he responded to a set of circumstances that could have gotten out of hand anyway. Three or four of these guys would maybe have given him a beating. He grabbed the sergeant maybe as a way of asserting a different dynamic.

Another example. We all went to the Sinn Féin Ard-Fheis in Dublin one year, in the early 1980s. Myself and a man called Gerry Doherty were travelling together, and we hit this tailback of cars before we got to the bridge. And Gerry said to me, ‘That’s Martin McGuinness.’ This was before we got to the bridge. We knew that he was going to the Ard-Fheis and he was ahead of us. The tailback went on so long we left somebody else to drive the car and we went on foot to the bridge and then on up. Martin McGuinness had this car across the bridge and was refusing to move it. They wanted him to drive to a search bay and he was refusing to do it. ‘You can search here or you can stay here all night.’ In the end they gave up – they sent for an inspector and he said, ‘Take a look at the car and then let him go on.’ The Brits couldn’t resist trying to subjugate him, but they were learning that there was no point in taking this guy on.

Sometimes he created a situation just for devilment. We travelled together everywhere and it’d depend what mood we were in. The first time he ever cursed at me it was because he felt it was all right if he started a row with the police, but if I started it, it wasn’t! ‘I never fucking know what you’re going to do!’ But you got fed up being stopped all the time. In this instance I had started it – picked up on something they said, or refused to do something they said to do – though usually I was the peacemaker. Normally it would be him who would start the aggro – and he wouldn’t need a carful of people to back him up either, he’d do it on his own.

***

Martin was quite a devout Catholic – which I am not. And we used to have some arguments about it. But he genuinely did have his faith. Bishop Eddie Daly had a sort of love-hate relationship with Martin. Daly condemned the actions of the IRA many, many times, and Martin would challenge him publicly. The weakness of the Catholic Church in that kind of argument was that they didn’t balance it with the injustice of the state or the British, and they certainly didn’t offer an alternative. That debate around an alternative was maybe the seeds of the peace process. You want the IRA to stop? OK – give us an alternative. Bishop Daly would have been condemning and issuing edicts about IRA funerals in churches.

At other times the bishop would engage with the IRA. There might be a family in trouble and he thought he could find help. There were issues relating to conscience or social justice which you could put forward and discuss. It wasn’t exactly a back channel, but there was always a dialogue.

Years later, Daly, when he was the bishop and Martin was in the IRA leadership, said he had come to recognise that McGuinness was at peace with his conscience. In other words he believed in what he was doing. The bishop was pressed on this and said he didn’t think that this could be interpreted as meaning that Martin McGuinness made choices he had to live with but wished he had done something different. He said it was quite possible if those circumstances were repeated that Martin McGuinness would have made exactly the same decisions. That was an insight that could only have come from private conversations – certainly I wasn’t party to it. But when I heard Eddie Daly saying that, I said to myself, ‘You’ve taken the time to explore this with Martin.’ So Martin was at peace with his conscience, and that’s not to be interpreted as him wishing he had made different decisions.

Martin was also quite a progressive thinker. I attribute to him two things: one was ending the policy of ‘disappearing’ the bodies. There was an informer shot in Derry, a man called Duffy, who had been buried secretly. Martin was opposed to the practice of ‘disappearing’ bodies and made a direct intervention; there are famous photographs of the body being located and the hearse waiting at the border for the family. Then, in subsequent years, there was the ending of the policy of kneecapping. He was the person who challenged the thinking behind this policy, querying whether it was an appropriate response. Was it a solution to the problem? It wasn’t.

He was a strategic thinker even when he was a young man in his late teens and early twenties. He had developed a strategic capacity over all those years. So when it came time for the peace process, there was nobody with a clearer understanding of what that meant. His role – public now but secret then – was of being the contact point with the British government – the back channel. His appointment as the sole point of contact and his ability to deliver messages on behalf of the republican movement – and to deliver them in a coherent and sufficiently succinct manner – meant that Martin was completely on top of that brief.

In the early days such contact with the British was very dangerous. There were people who were involved in the 1970s in ceasefires and there were people who were involved in negotiations during the hunger strikes – particularly the first hunger strike – where the commitments that were given were reneged on. All of that left a view among some – which was a disaster if it had prevailed – that you couldn’t trust the Brits in any circumstances. In effect that was saying, ‘There’s nothing else for it but to shoot people and blow the place up.’ Martin’s argument was that everybody has interests, everybody has outcomes in mind, nobody is operating on an agenda that’s fixed. We are going to sort this out. Now Maggie Thatcher may have been fixed. Martin McGuinness, on certain issues, might have been fixed. But on the overall situation, nobody believed that sustained warfare for generations was possible. There had to be a purpose and a direction, and there had to be momentum.

Whenever we produced the discussion documents – internal but subsequently published as A Scenario for Peace – it laid a claim for a very under-developed peace, though it was fairly revolutionary for its time and context. A Scenario for Peace was an attempt at laying a foundation and putting down a marker on record that republicans were interested in peace.

This was the late 1980s. AScenario for Peace was, I think, written up around 1987. Then you’d the talks with the Social Democratic and Labour Party [SDLP], which followed that year. Then you had things like the Downing Street Declaration, the contact between Gerry Adams and John Hume, the publication of Towards a Lasting Peace in Ireland. All those things really required people with prescience and vision, such as that ascribed to Gerry Adams – though others also had to have the same skill-sets. Martin had those skill-sets. It wouldn’t have got off the ground without Gerry’s vision and Martin’s leadership. It was just a priceless combination.

As well as that, Martin was consistent. The evidence for that is his attitude to rolling devolution in the James Prior years. [In 1982 British Secretary of State James Prior set up a Stormont Assembly with limited powers, which were to be increased as it learned to operate constructively.] Martin was elected to that and I was his director of elections. Once elected, he was immediately aware that it was going nowhere. Martin knew instantly that this Assembly and rolling devolution were a dead duck. We forced the SDLP to pull out of it.

Never at any time was Martin an isolated figure in the republican movement – although it was dangerous at certain times when some very senior people in the IRA were saying that there never again would be a ceasefire, because the decision to call a ceasefire in 1975 was abused by the British to introduce Ulsterisation. [An initiative by British Secretary of State Merlyn Rees to replace units of the British Army with the local RUC and Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR).] Despite this, Martin never let go of the possibility of a negotiated outcome and was pursuing it through contact with British military intelligence.

***

Martin clearly loved Donegal. He went there every chance he had down the years – to walk along the beach at Lisfannon, to go to his mother’s home in the Illies, just outside Buncrana. He was a fly fisherman, but he very rarely would have been fishing on his own. There’s a great fisherman in Derry, who doesn’t live that far from here, Jamesy Quinn. He taught him all he knew. He’d have been a constant companion. There was also former republican prisoner Gerry Crossan, who was a formidable fisherman. So it wouldn’t have been solitary. The walks along the banks of the River Fahan [a few miles from Derry] would have been with his family – the children and his wife, Bernie.

He also wrote poetry, though where he got the time to I don’t know. I remember us driving up and down from Derry to Belfast in the days before the by-pass at Toome, when you had to drive through Toome. And there was this local character; you would have seen him in the mornings, standing outside the shops as you’re driving through. We’d have been coming home again in the evening and the poor craytur would have been slumped on the ground with drink. So Martin had figured out by observing him that there was someone who looked after him and loved him: out each morning clean, dressed, fed, upright; by the evening, collapsed at the side of the street with a feed of drink. Martin wrote a beautiful poem about it. He read it to me as I was driving. I said, ‘I want you to give me that poem’, and he said he would – and he fucking never gave it to me! And when I went looking for it, I challenged him about it, and he couldn’t find it then. But that’s the kind of person he was. We were driving and thinking about all the high politics we thought were extremely important to the whole world, and in the middle of it he had taken time to observe this man whose name he didn’t know. I find that revealing about the kind of person he was.

***

I found out about his illness at pretty much the same time as everybody else. Bernie and I had a conversation – an unconcerned conversation – about this kind of ticklish cough, and she made a remark that came back to me like a hammer-blow subsequently when more detail emerged. This was late 2016 and before anything else emerged – it was just this ticklish and persistent cough. She told him to go and get it checked and said to him, ‘I think that’s your heart.’ Now why she said that she doesn’t know – I asked her – but it turned out she was right.

He went and got tests. Initially there was no alarm, but there was a question about the quality of the blood. It turned out that this was the source of the problem – his body was producing too much protein. And it was far too late at this stage to fix – major damage had been done to a valve on the left side of his heart. They developed a regime of treatment that was to run from the turn of the year to August of this year [2017] – that’s how serious it was. At this stage it was fairly obvious to me it was a life or death struggle. The prognosis from the doctors was that they had a treatment devised that was going to succeed, going to save him, but it was going to take time and it was going to be a long and difficult process. It was in that context Martin made the decision not to stand for the 2017 election. He knew he was going to be incapacitated.

Right up to the weekend before he died, the doctors were still confident. His family obviously were blinded to what the situation was, because he was in intensive care for about three weeks before he died. I hadn’t seen him during that period because I respected the family and I knew the kind of man Martin was, that he wouldn’t want people interfering. I know one or two people went over, but I quite consciously and deliberately stayed away. It was an awful shock when he died.

The last time I saw him was just before Christmas. We live just round the corner from each other. He was in the house after he’d been diagnosed and I left him up a collection of Seamus Heaney poems that I had. I’d always meant to give it to him. It was a very good quality book that was presented to me, but he had a far greater interest in Heaney than I did. Seamus Heaney and I had a wee bit of history. We fell out over whether he ever addressed the core of the situation here.

At Martin’s funeral I was devastated. I knew he had arrangements made to retire in May of this year. One of the things that impressed him and reinforced his decision was the fact that I’d retired and was obviously so happy. He’d see Mary Lou and me about the town, just wandering about and having time to ourselves.

He and Bernie contributed so much of their own time to everybody else. His house never emptied. I had a far greater discipline. We run offices and I used make myself available to people, but I never encouraged the idea of people suiting themselves and coming to the door, except in emergencies. But Martin had an open door. I don’t know how he did it.

He was first and foremost a friend. Probably my closest friend. I’m not claiming I was closer than anybody else – he was hugely admired within republican circles, as reaction to his death would testify. But we could speak at a personal level and took an interest in each other’s family. So I lost a friend first and foremost, and I think we’ve all lost, and the unionists in particular have lost, the best friend they could have had.

Stormont opened a book of condolence for the family and it’s a very interesting read. Every single party, including the DUP, signed it, made comments. My own contribution – and I thought about it – was a play on the Seamus Heaney line from ‘The Cure at Troy’: ‘Martin was a man who made hope and history rhyme’. That’s how I saw him. He was a friend for fifty-odd years, but he was a man – a leader – who made hope and history rhyme.

2

Peter Sheridan

When I first went to the police in Derry in 1978 as a young Catholic RUC officer, Martin McGuinness would have been well known to officers of the city – or at least spoken about. The picture I got was of somebody who saw me as an enemy, somebody who was prepared to use extreme violence against me and police officers and the army in the city.

There was an element at that time that figured the way to prevent Catholics joining the police was to concentrate on attacking such Catholics. I was forced to move out of my house twice when people thought I should visit the next world before I wanted to. Obviously, when I was out on duty they couldn’t particularly pick me out from others. But the fact that I became over time a senior officer in the police in Derry meant I’d have been reasonably well known. As a result I became a focus of attention.

I have often thought about not just Martin McGuinness but the other people who were intent on killing me then. Personally, I never went to bed any night wondering whom I could shoot, kill or maim. Nor did I get up any morning thinking the same. And that included Martin McGuinness and others in the IRA. It’s not how I was brought up to think about people, as my enemy.

Martin was seen as somebody who was on the other side – the leader – and was involved, therefore, in what was happening, not just in Derry but further afield. But it certainly wasn’t a case of hatred. I’ve never hated anybody in life. I pride myself at working hard not to let others fall out with me. I remember stopping people in the street who would have been known IRA people. On those occasions I would have been at pains not to be antagonistic towards them, even if they were trying to antagonise me. There are very few people in life who I haven’t got on with, and that includes people in paramilitary organisations.

At that time, when we were searching people’s houses, I used to try to put myself in those people’s shoes. How would I have felt if the police were coming in, people I didn’t know, who I saw as the opposition, coming in and searching my house? How would I have felt about the way they left the house? I was always conscious of those things, particularly when I became more senior in the organisation – how we left people feeling.

I’d have stopped Martin at checkpoints several times in the city. There was no let’s-get-to-know-each-other conversation, but I didn’t find him objectionable to me. I didn’t find him rude or anything. I didn’t find him nasty in any way. I wouldn’t use the words unpleasant or objectionable. When I became more senior he’d have recognised me, but not in those early days.

I first met him formally in 1997, when I was in Downing Street with Hugh Orde. Tony Blair called a meeting where Sinn Féin were going to meet the police. It was part of the build-up to Sinn Féin supporting policing. So we met them in Downing Street that day.

We were in the Cabinet Office with Prime Minister Tony Blair, Jonathan Powell and one or two Northern Ireland Office [NIO] people. Then there was myself, Hugh Orde and Sinead McSweeney, who was our director of communications in the PSNI at the time. So we were all in the room first, and then in came Gerry Adams, Gerry Kelly and Martin McGuinness. I don’t remember any shaking of hands at the beginning of the meeting. Gerry Adams said something along the lines of ‘You’re welcome’ to me, and I quipped back, ‘You’d think it was your house – it belongs to him!’ – pointing at Tony Blair. There was no need for introductions – everybody knew everybody else in the room.

We sat at the cabinet table. They were on one side; we were on the other. Hugh Orde sat beside the prime minister and I sat beside Hugh Orde. Jonathan Powell sat on the other side of the prime minister and the NIO civil servants further on up. The discussion was about policing – very high level. I said, ‘My view from an operational perspective is, unless people down and around Shantallow [a nationalist working-class area in Derry] see a substantial change in policing within a year, this initiative for acceptance of the PSNI could be lost.’ I was asked some questions about policing. At that point we were reintroducing officers on bicycles back into the Creggan and we’d done it successfully. But I made the point that I was worried it wouldn’t last.

It was a professional, business-like meeting – there wasn’t any sense of personalities coming through. I think Sinn Féin at that stage were on a mission about what they wanted before they would join up with policing. I’d have seen Martin McGuinness quite a bit on television in the run-up to this. He and Gerry Kelly were probably more on the warm side. There was almost more distance at the table with Gerry Adams.

Tony Blair left the meeting slightly early to go to something else and Jonathan Powell continued in his place. At the end there was a shaking of hands. When that began to happen, I remember thinking how one of my father’s friends was murdered by the Irish National Liberation Army [INLA]. He was a Protestant man engaged in nothing – a businessman in Derry – who was mistaken for a police officer. His daughter was a friend of mine. She wouldn’t have got beyond the fact that these sorts of people had murdered him.

This was the image that came into my head as I was going to shake hands: knowing that, and having walked behind the coffins of other murdered colleagues and so on, and conscious of how this meeting would be read by the police organisation, the handshakes felt awkward – something not quite right about them. It took literally a couple of seconds. I’d never met Martin to shake hands with him before. So I shook hands with Gerry Kelly and Gerry Adams. And as I shook hands with Martin I said, ‘Your mother makes good soup.’ He looked at me and said, ‘How’d you know my mother makes good soup?’ And I said, ‘I’d a bowl of it on Saturday.’ And he looked at me and said, ‘Where’d you get a bowl of my mother’s soup?’ So I said, ‘You come back to the next meeting and I’ll tell you then.’

What had happened was that the previous Saturday I’d bought a book in Dublin called Nell by Nell McCafferty. So I rang her and said, ‘I refuse to read your oul’ book unless you sign it for me.’ She said, ‘I’m going to the Bogside at the weekend to see my mother.’ So I thought I’d nip over on the Saturday morning and get the book signed.

I drove over and Nell met me at the door, the hair standing on her head, in the dressing gown, fag in her hand, and insisted that I come in to see her mother. It was a small terraced house; her mother had had several strokes and she was in the living room in the bed – they’d made the room a bedroom. It had a window out onto the street almost. So Nell brought me in and said, ‘I want you to meet my mother’, and sat me on a commode at the side of the bed. I said to her, ‘It’s probably a good place for me to sit, Nell, because I need to be out of here soon.’

She was having a conversation with her mother, who was having difficulty speaking at that time, and I discovered that her mother’s grandfather was known as ‘the good Sergeant Duffy’ – he had been a Royal Irish Constabulary officer. So we were talking and the mother produced this bell-push that they’d had an electrician rig up for her, so she could call for assistance during the night. But when Nell was making the bed that morning, she’d pulled the covers and pulled the wire out of the thing. So Nell hands me this bell-push and a huge screwdriver and says to me, ‘Can you fix that f–ing thing?’ I started putting the wires back into it and she’s shouting in her mother’s ear, ‘He’s a top cop, Ma!’ Meanwhile I was aware there were people passing outside and my car was parked out there.

So anyway I fixed the bell push and then Nell brought me in for a bowl of soup in the kitchen. I was having the soup – I didn’t want to show I was afraid and didn’t want to hang about – and she had this wee tray with a doily on it, pieces of French roll and a bowl of soup. Nell is not the most domesticated.

So anyway, she gave me this soup and she said, ‘Do you know who made that soup?’ And I said, ‘I know you didn’t make it anyway.’ And she says, ‘Peggy.’ And I says, ‘Peggy who?’ And she says, ‘Martin McGuinness’s mother.’ So I said, ‘Are you trying to poison me?’ Eventually I took a police business card out of my pocket and wrote on it ‘Peggy – wonderful soup’. And I gave it to Nell and told her, ‘You give that to Peggy the next time you see her.’ And Nell said, ‘Oh, she was in the other night to see my mother’, and she set the card up on the mantelpiece.

What I didn’t know was that on the way back home from Downing Street, Martin must have rung his mother and his mother said, ‘Martin, there was a cop in Nell’s house on Saturday.’ And in Nell’s book [Nell rewrote her book with a new chapter about the first cop that’d come to her house since 1969] it says that he told her, ‘Me and Gerry Adams negotiate with the peelers, not you and Nell McCafferty’s mother.’

***

That following summer of 1998 there was an Apprentice Boys parade banned from the walls of Derry, and all sorts of prophecies of Armageddon were made. I had responsibility for all events on Apprentice Boys’ day. So I was based in Derry and there were about 1,200 police and soldiers on the streets, but in the end it passed off generally peacefully.

But in Dunloy [a small nationalist village in County Antrim] the commission had given the Apprentice Boys permission to walk out of the Orange Hall, go 200 yards down the street, turn back again, get on the bus and go. But the street had been blocked by people – probably at that time Sinn Féin people – in the middle of Dunloy. There was a kind of stand-off and the Apprentice Boys hadn’t left the hall. You could sense that it was building up throughout the day. And the rallying cry had gone out for the Apprentice Boys in Derry, when they were finished the parade, to travel home by way of Dunloy. That was the intelligence we were getting.

So I could feel another Drumcree building up. [In 1995 there had been a massive stand-off between thousands of Orange Order marchers, the police and local residents at Drumcree.] We even had a water cannon on the way from Belfast. But I took one last throw of the dice and rang somebody I knew in the Bogside and asked if there was anyone who could do anything about this. So he said, ‘Hold on.’ He hands his phone over and then a voice says, ‘Who’s this?’, and I said, ‘And who’s this?’, and the voice says, ‘Martin McGuinness.’

I told him about the situation and I’d no sense he was going to do anything about it. It was a fairly cold, not all that engaged conversation. But about twenty minutes later I had a call from the guy I’d rung and he said, ‘What happens if I get caught for speeding through Greysteel?’ He was obviously saying they were on their way. I told him not to kill anybody or knock anybody down – if it’s only speeding we’ll hopefully resolve that.

So they got to Dunloy and between us we were able to resolve the situation. In policing terms we were within our rights to move the people off the streets because the commission had said the march was allowed to go down. But big burly cops in riot gear hoofing people off the streets is a no-win for policing, even though you’re legally in the right. They still wanted some things like the police taking off their riot gear. But we resolved it between us, and I often say it had to do with the bowl of soup I had in Nell McCafferty’s house. Or the handshake in Downing Street, treating him like a human being. I don’t know, but I think out of that experience both of us knew we were trying to achieve the same thing. We were going to come at it from different directions – there were different audiences, after all – but we both wanted effectively the same thing, which is a more peaceful place here.

Further to the soup story – in 2012 my brother was in Eason’s bookshop in Derry, buying his wife a cookery book for Christmas. He spotted Martin McGuinness, who was doing the same thing, and my brother wondered, ‘What do I do here?’ Martin was deputy first minister at the time. So he lifted this book – probably the cheapest book he could get in the shop – Two Hundred Soup Recipes – and he goes over to Martin McGuinness and says, ‘Would you mind signing this?’ And Martin said, ‘Would you mind buying it first?’ So he says, ‘Oh yes, I’ll buy it, I’ll buy it.’ He bought it and asked him to write, ‘If you liked my ma’s soup you’ll like these.’ So McGuinness says, ‘You want me to write that on it?’ And my brother says, ‘Yes.’ So he’s halfway through writing it and Martin looks up and says, ‘Are you a cop?’ My brother said, ‘No, no.’ So Martin writes on it and signs it, and on Christmas morning I get it as a gift. I still have that book.

***

Given what I knew about Martin’s background, I was puzzling over how to make sense of his life. I put it in three phases. I didn’t know him in the first twenty years of his life, when he grew up in poverty with an outside toilet, discrimination, gerrymandering, housing – all the things that happened in the Bogside. I wasn’t exposed to that. I knew of him in the next twenty years, which was when he responded to that discrimination, etc., through violence. But I would see that Downing Street meeting as a marker after which I got to know him.

We met umpteen times after that and it was always an easy conversation. It was never one of those, ‘Will you and me and Bernie and Michelle go on holidays together?’ things, or ‘Let’s go out for a meal together.’ But it was always a pleasant conversation with him. I met him in Derry one Sunday – we happened to be in the same restaurant and we had a conversation there. So I got to know him; and I think I also got to know him by watching what he was doing in politics.

There are people who’ll look at the middle twenty years of Martin McGuinness’s life and that’ll be the only bit they’ll comment on and look at. There are others, however, who’ll only look at the last twenty years – Bill Clinton did that at his funeral, looked at his last twenty years. If I only focused on the twenty years that I knew of him, I’d come up with a certain viewpoint, whereas I can look across when I knew him and also have some recognition of where he came from. I was head of murder, organised crime, intelligence and all, so I’m not naïve about the middle twenty years. But I do have some difficulty with people now who couldn’t convict him in this life but are trying to convict him in the next, when he’s not here to defend himself.

People consistently ask me about his involvement, and I say, ‘We didn’t convict him in this life – it’s not my job to try and convict somebody when they’re dead.’ And I think it’s unfair to people. If you believe in justice and law, then you can’t just fire stuff around – that he was involved in this, that and the other. It just strikes me as morally wrong, ethically unfair to do that.

I came to like Martin. It wasn’t that close a relationship. But this guy was very personable. I didn’t get any impression that this guy hates you or hates what you stand for. When we talked, it was a warm conversation.

I don’t think his was a set-up charm. I think this is who he was – he was a people’s person. He liked people, had an understanding of people. Maybe one of the reasons, in the second twenty years of his life, why he got caught up in violence was because he was so passionate about people and he thought that that was the only way to help them. I doubt very much if there were many people, once they engaged with him, who wouldn’t have said there was warmth in him. I’m not naïve – I didn’t come up the Foyle in a bubble. Like any of us in life – and I’m sure he was the same with me – he was trying to work out where this guy really was coming from. And I think we ultimately came to a conclusion about each other. Certainly in later years, he had the same desire to help people, to change things.

We engaged in conversations about violence. He did umpteen events for us in Co-operation Ireland [an all-island peace-building charity]. Trying to deal with the past was always a big issue. I had the view that we are never going to do justice to the scale of injustice on any side.