Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

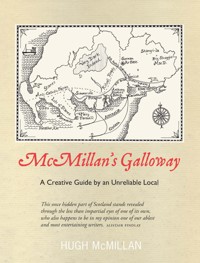

McMillan's Galloway, a witty and irreverent look at contemporary Dumfries and Galloway, provides a suitably individualistic snapshot of a place which operated for so long as an independent entity completely separate from its neighbours, Scotland and England. McMillan takes us on a rollicking tour from the Mull of Galloway to Langholm, through land once shrouded in myth and populated by warriors, emigrants, fairies and liars, rooting out the truth and the fiction and frequently confusing them.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 412

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

HUGH MCMILLAN was born in 1955 and lives in Penpont in Dumfries and Galloway. He is a poet and writer. He was the winner of the Smith Doorstep Poetry Competition in 2005, the Callum Macdonald Memorial Award in 2008, a winner in the Cardiff International Poetry Competition and was shortlisted for the Bridport Prize, the Michael Marks Award and the Basil Bunting Poetry Award in 2015. He has been published, anthologised and broadcast widely in Scotland and abroad. He has also collaborated with artists in projects supported by Creative Scotland, including two, ‘Forgotten Doors’ with Hugh Bryden and ‘Elspeth Buchan and the Blash o God’ with Robert Campbell Henderson, of direct relevance to Dumfries and Galloway. In 2020 he was appointed a ‘Poetry Champion’ by the Scottish Poetry Library. In 2020 he also began #plagueopoems, a unique poetry video blog featuring 130 poets from across the world in lockdown.

By the same author:

Tramontana, Dog & Bone, 1990

Horridge, Chapman Publishing, 1995

Aphrodite’s Anorak, Peterloo Poets, 1996

Strange Bamboo, Shoestring Press, 2007

The Lost Garden, Roncadora Press, 2010

Thin Slice of the Moon, Roncadora Press, 2012

The Other Creatures in the Wood, Mariscat Press, 2014

Not Actually Being in Dumfries, Luath Press, 2015

Sheepenned, Roncadora Press, 2016

Helipolis, Luath Press, 2018

The Conversation of Sheep, Luath Press, 2018

Dodeka, Roncadora Press, 2019

Source to Sea, Roncadora Press, 2020

Haphazardly in the Starless Night, Luath Press, 2021

Whit If? Scotland’s History as it Micht Hiv Bin, Luath Press, 2021

First published 2016

This edition 2023

ISBN: 978-1-910324-69-1

Typeset in 10 point Sabon by

3btype.com

The author’s right to be identified as author of this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Acts 1988 has been asserted.

© Hugh McMillan 2016, 2023

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword: Alistair Findlay

Introduction

A

Anthony Hopkins’ Bench

Anwoth

Art

Away With the Fairies

B

Badges

Bank Managers, SR Crockett and the British Union of Fascist Lifeguards

Barbados House

Barrie, JM

Berthing the Big Boats

Bobby Dalrymple, Winston Churchill and the Science of Coincidences

Bodkin

Book Town

Books: Existing, Made-up, Vanished, Made of Wood

Bram Stoker and the A75

Burns, Robert

Burns, his Murder

C

Carsethorn

Carsphairn

Cats or Bawdrons

Cavalry and the Ode of the Oatcake

Chrissie Fergusson

Clatteringshaws Hydro-Electric System

Colin’s Father on the Moon

Conversation about Davie Coulthard the butcher in Dalbeattie

Covenanters

Crossmichael

Curling

Cut Off

D

Dalbeattie Civic Week and Lawrence of Arabia

Darkness and Light

Deafness, Oily Fish and Hugh MacDiarmid

Disasters

Domino Lingua

Dorothee Aurelie Marianne Pullinger

Douglas Fairbanks Junior

Drink & Accordions

Duke of Elsinore

Dumfries

Dykers

E

EA Hornel

Eddie P

Elephants

Emigration

F

Fatal Tree, A

Feisty Women

Fergus of Galloway

Ferry Bell Tower

Festivals

Food Parcels

Foot-and-Mouth

Frontiers

Funerals

G

Garlieston in Darkness and Light

Geniuses

Geofantasapsychiatry

Ghost Landscape

Ground Control to Major Gong

H

Haaf Netting

Haunted

Hollows Tower

I

Insane

J

Jailbirds

Jane and Jean: Burns Women

Jarama

Jerry Rawlings

Journalists

K

Killantrigan Lighthouse Keeper, 1913

Kirkcudbright

L

Lachy Jackson’s Bet

Lauren in Snaw and Flud

Levellers

Love and Death

M

MacBeth in Dumfries and Alexander Montgomerie

Machars

Magic and Michael Scott, Superhero

Magna Carta

Makar

Mermaids

Midnight in Stavanger and Eric Booth Moodiecliffe

Minerva, Dumfries Academy and JM Barrie

Mining

Miracles

Money: Lost, Made, Burned

Mons Meg, Munitions and CND

Mull of Galloway

Munitionettes

Myrton, Magic and Monreith Bay

N

New Arrivals

Nicknames

Nith Cross

No Deid Yet: Two Galloway Memorials

O

Old Aeroplanes, Intrepid Fliers and the Question of Toilets

Old Tongue

P

Palnackie

Pies

Pine Martens

Pistapolis

Plagues and Radiation

Poetry Highway

Pubs: Where Have They Gone?

Q

Queen of the South FC

R

Religious Maniacs

Ritual Roads

S

Sailors: Real and Dodgy

Shooters

Shuggie MacDiarmid (Big Shuggie)

Siller Guns

Slow Tourism

Smugglers

Speugs

St Trinians and Kirkcudbright

Stagecoaches – Not the Company, the mode of transport

Stanes

Strong Old Men

T

Teachers: Class-War

Things that Go Blink in the Night

Tides

Tinkers and Free Travellers

Tune Carrying

U

Ugly Enormous Megatherions

V

Village of the Damned (Creetown)

Voices

W

Walkers

Wandering Poets

War

War Machines: Supermarine Stranraer and HMSNith

Weans’ Tales

Weather

Willie McMeekin, Dyker

Woodcutters

X

X-Factor

Y

Yes and No & Amy McFall

Z

Zeitgeist, Thomas Carlyle, Walter Scott, Frederick the Great and Hitler

And Finally, John Mactaggart

Gazetteer

Selected References

Acknowledgements

I have included these excerpts of poems or poems by contemporary poets with their permission, that of their publishers, or the holders of their copyright.

‘Sundaywell’ by Donald Adamson (from Both Feet off the Ground, Dumfries Libraries, 1993), ‘What’s Human’ by Jean Atkin (from Not Lost Since Last Time, Overstep Books, 2013), ‘Curling’ by Angus Calder (from Waking in Waikito, Diehard Publishers, 1997), ‘Tall Poppies’ by Kirkpatrick Dobie (from Collected Poems, Peterloo Poets, 2003), ‘Spelling Galloway’ and ‘The Cottage Garden, Clatteringshaws’ by Davie Douglas (from Spelling Galloway, Grey Granite Press, 2013), ‘Epistle to Twa Editors’ by Bill Herbert (from Mr Burns for Supper, Greit Bogill Publications, 1996), ‘Seagulls’ by Brian McCabe (From Body Parts, Canongate Press, 1998), ‘Jarama Valley’ by Alec McDaid (from The Book of the XV International Brigade, The Commissariat for War Madrid, 1938), ‘Mr Burns for Supper’ and ‘A Knell for Mr Burns’ Willie Neill (from Mr Burns for Supper, Greit Bogill Publications, 1996), ‘Dundrennan, Greyness, Lockerbie, The Marksman and Peel Tower’ by Willie Neill (from Selected Poems, Canongate, 1992), ‘From Criffel to Merrick’ by Liz Niven (From Cree Lines, Watergaw, 2006), ‘In Memoriam Solway Harvester’ and ‘Devorgilla’s Legacy’ by Liz Niven (from Stravaigin, Canongate, 2001), ‘Douglas Hall’ and ‘No Summer Yet’ by Stuart Paterson, ‘Memorial and The Promised Land’ by JB Pick (from Being Here, Markings, 2010), ‘Pilgrim’ by Tom Pow (from Landscape and Legacies, Lynx, 2003), ‘Shopping Trolley River Nith, Mennock and Tom Pow on a Bike’ by Rab Wilson (from Life Sentence, Luath Press 2009)

Foreword

WHEN HUGH MCMILLAN asked Luath to consider re-publishing his Gallovidian Encyclopedia, commissioned by the Wigtown Book Festival, I knew we were in trouble. The publisher, assuming I had read it along with the ‘new and selected’ anthology of his poetry I was currently chortling over, suddenly asked whether it was an Encyclopedia or a Gazetteer? I said ‘pass’. Curiousity aroused, he asked, what’s it about? I said ‘Hugh McMillan’, and he said ‘pass’. Just joking, at least regarding that last bit. When I asked Hugh McMillan whether it was an Encyclopaedia or a Gazetteer, he of course said ‘yes’, which confirmed my strong suspicions that it was neither.

It was, in fact, something much more important: a writer’s tour – incorporating occasional intemperate rants – round this rather off-the-beaten-track corner of south-west Scotland, with its colourful Covenanting and witch-drowning past, hopefully all behind it now, its huge skies and long coastline, its rural, still-working landscape, its Wigtown Book Town, its Kircudbright Artist’s Colony, its Dumfries Pubs and their denizens (lovingly detailed by Hugh), its Tory mps and msps, still left in Scotland, and Hugh McMillan, its indigenous award-winning poet and anarcho-syndicalist Yes-campaigner, former Dumfries Academy history teacher, and someone you should not approach after six-o’clock mid-week, or any time over the weekend, or you might well end up in a book like this or, worse, a poem.

One could say that McMillan’s Galloway is an Encyclopaedia in the same way that the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is a travel book. His Galloway is less a geographic than an imaginary space, an imagined place more like, built on and in dialogue with perspectives borrowed from those who have written, drawn, filmed or simply visited it in the past, including the recent past (see Anthony Hopkins’ Bench) and including those who have lived and survived here over the centuries, its extremists and its ordinary people, who were often both – all of whom McMillan savours and argues with, or about, in ebullient and informative style as befits his literary and historical background and local cultural pursuits and interests.

In this fashion, he draws on writers, artists and film-makers associated with the place – religious fanatics, heretics, British fascists, Levellers – and the ordinary working population from tree-fellers to dykers – as witnesses to ‘people’s history’ and so to their own epic survival and existence, revealed through their own language, inner thoughts, epic grudges and fluent expletives undeleted. Into the latter category, under the letter ‘C’ – alphabetical arrangement being one of the few resemblances Mr McMillan’s book actually shares with normal Encyclopaediae, along with richly detailed subject matter – comes the entry titled ‘Clatteringshaws Hydro Electric System as described by Keith Downes in the King’s Hotel Dalbeattie 21 January 2014’ – whose title alone probably qualifies as ‘found poetry’:

It’s f ...... incredible, see the loch we ca Loch Ken, it’s an artificial loch, ye ken? On an old tidal system, 6 dams, a third o the power o the whole Stewartry comes fae that, ken, it’s a f..... great system, I’m proud as f.... of it. Built in the 1930s ken. It’s incredible. I’d like you to see it. You’d be f...... dancing for joy when you see it, mukker, f...... dancing. Feenished in 1937, yon Tongland, what a great wee power station. See I’m a Stewartry man, born and bred. F......Dumfries, C’mon now Dumfries has stolen New Abbey frae us, f........ Southerness, f....... Creeton’s awa. It’s a f.... land-grab by Dumfries, it’s a f...... disgrace. A f...... conspiracy pure and simple. I’m makin too much noise am I? Should be shoutin it frae the rooftops. F...... disgrace. Pure and simple.

At one and the same time, this extract passes as oral history, cultural history, literary history, industrial history and social history – ‘people’s history’ – rubbing shoulders with the real, the written, the imagined, the rumoured, the unprovable, the uncertain and the downright vexatious and funny. The same mix informs the bulk of the book. Our scribe, being a Latin scholar, and as shrewd as a mole-catcher, is of course wise enough to have guarded against any possible defamation suits by quoting Tacitus and David Malouf – ‘Maybe, in the end, even the lies we tell define us’ – which just might be enough to keep him from litigation and the publisher out of the small-claims court.

Mr McMillan’s book, as he explains in his Introduction, initially set out in his own mind to be a kind of sequel to John Mactaggart’s 1824 Galloway Encyclopedia, in some ways seeking to ‘follow in the footsteps of one of the region’s great self-taught and quirky geniuses’. He certainly manages that, scholarship rubbing shoulders with quirkiness verging on genius on many occasions, but I think there are more profound parallels to be drawn with Dr Johnson’s great Dictionary, as described in this extract from the British Library: ‘Thus the quotations reflect his literary taste and rightwing political views… Johnson was criticised for imposing his personality on to the book.’ Of course, this is exactly what modern readers value most in literature, subjectivity and partiality, so long as the personality is strong enough to bear the scrutiny. What Hugh McMillan and Dr Johnson share, therefore, is not their politics, extreme though both are in forwarding their own opinions, but their extreme love of their native and also regional languages, especially as regards what Dr Johnson calls their ‘energetic unruliness’, matched by their own willingness to go to wherever that leads, and taking their readers with them. And like Dr Johnson in his epic work, Hugh McMillan is right bang in the centre of his book, whatever one wishes to call it, which for me is one of its chief delights.

This said, it was not until the letter ‘D’ was crested in what follows, specifically ‘Dalbeattie Civic Week and Lawrence of Arabia’ (please don’t ask, just read), that another source of Mr McMillan’s inspiration was allowed to escape, and which readers should perhaps be aware of from the outset, the American writer, Hunter S Thompson, author of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and many other titles. As Mr McMillan describes the influence: ‘Hunter S Thompson invented the term gonzo journalism which is reporting that makes no claims to objectivity at all and which often includes the writer himself as part of the story’. Indeed, and I would say, thank goodness for that. And so, dear reader, you have now been amply warned, for this once hidden part of Scotland now stands revealed through the less than impartial eyes of one of its own, who also happens to be in my opinion one of our ablest and most entertaining writers – pure and simple – as Mr Keith Downes himself might have put it, down in the Stewartry.

Alistair Findlay

Introduction

Ubi solitudinem faciunt, pacem appellant.

They created a desert, and called it peace.

TACITUS ON CALGACUS

The Galloway landscape with its bleak mists and mudflats, glens and mountains, empty moors and ancient moss-covered stones has been the backcloth for countless poems, novels and films. It’s a place where people have left and ghosts and whispers fill the gap: the crack of a shotgun, the fields of white turbines in the hazy distance, the ruined castles, the stars at night. It is a land made for dreams and nightmares. It is where the fairies last bade farewell to Scotland. A battlefield across a thousand years of history, its scattered people are still suggested by place names in Gaelic, Welsh, Norse, English. It was a land cleared of people, no less ruthlessly than in the highlands, a lawless land, a void filled by anarchic smugglers and reivers and levellers. It was a land of walkers, poets, geniuses. And now what is it? Traditional industries are dead. There are tourists of art, of history, of poetry. There are shooters, a book town, dark skies: Galloway is a blank page for people’s fantasies. People come here, and they still work here, live and die, but overall, as it has ever been, the rhythm to life is the steady bleed of Galloway’s young, taking their individualism and talent somewhere else.

Dumfries and Galloway has always been my home, my stomping ground. It is where I met my friends, my loves, it is where my kids were born, where I worked, where I found my sense of history, where I became a poet. All that would disqualify me from writing anything objective or scientific about the place but luckily I am required to do neither of these. Instead I am required to follow the footsteps of one of the region’s great self-taught and quirky geniuses, John Mactaggart.

Mactaggart was born of a poor family in Borgue. He did not have much patience for school but somehow, as it worked sometimes in the 19th century, the fact he had no qualifications at all did not stop him becoming a respected engineer, poet and writer. He published his Scottish Gallovidian Encyclopedia in 1824 and it was withdrawn from publication the year after following complaints by relatives of some of the people in it. He went to Canada to work and returned to die at the tragically young age of 38. At the time of his death a huge narrative poem called the Engineer was unfinished and unpublished. Cut forward 89 years and I am having a telephone interview for a commission to write a sequel to the Gallovidian Encyclopedia. I have just emerged from the Black Sea, covered with mud and full of rakiya. I envy other countries their independence, their certainties, but it can be boring knowing who you are and where you’re going. Did I say that in the interview? The phone line wasn’t very good and neither is my memory. Rakiya is tasteless but extremely powerful. After drinking it in Plovdiv once, I’m sure I saw the Kaiser on a surfboard. In the interview my voice has wings. I promise that it will be funny, and that it will be eccentric. I get the job. This was never going to be a work of ethnography, though it has drawn in the most part from the things people have said to me over the last several months or in the past. The stories here have not been scientifically collected but trawled at all times of the night and day. Some I have checked, but not all. What is truth after all? As a broken-down old history teacher I know the slipperiness of facts. This book unashamedly builds a shooglie layer of tales on those that have come before. Don’t be fooled however into thinking they’re all lies – some of the more outlandish ones have even come true in the gap between editions. I recently received, for instance, a video tape in which Anthony Hopkins confirms his ownership of the eponymous bench mentioned in the first extract below. At least, I think it was him.

Sometimes I have looked for resonances, echoes from Mactaggart or further back to posit a continuity or a coincidental link. It was fun doing that. Resonances remain as clearly as if they were caught still echoing in stone, and I have worked on ripples from the past as well as the testimony of living people. I have also injected myself, gonzo like, into proceedings throughout, and in this I am following the example of Mactaggart whose Encyclopaedia was very much Galloway through one very individual set of eyes.

Mactaggart’s book was rich in Scots, a language that has been very much driven underground in the last hundred years, when so-called Standard English, a completely artificial construct, was thought of as the way to speak if you wanted to get on in life. Many of the people I spoke with recall being forbidden to, and even beaten for, speaking Scots in school. It has led to a loss of identity, a kind of linguistic disenfranchising which I feel very keenly myself. My mother was a native Gaelic speaker and my father’s family, all miners from South Ayrshire, were Scots speakers, but ideally placed at the crossroads of two ancient tongues, I was left doing my version of the BBC because ‘English was the language for scholars’. Scots as a commonly spoken language exists now, it seems to me, only in pockets in rural Wigtownshire and, most proudly, in the Upper Nith Valley where the schools take a keen interest in it. Scots words and phrases still exist everywhere, however, and I have included them here, or at least the ones I heard on my travels.

Also, like Mactaggart, I have filled the book with both poetry; mine and that of others I admire. We are lucky to be having a literary renaissance in Dumfries and Galloway, not that the rest of the country pays a blind bit of heed, and we have an excellent crop of poets with local, national and sometimes international reputations. I have used their work, though knowing only too well what a tricky bunch they are, I have been keen to seek their permission. If I missed anybody, I apologise.

Like the original Encyclopaedia, I hope this volume is unique, full of fun and good poetry. Although Mactaggart would recognise some things in here, the same feudal arrangements seem partly in place for instance, other things would be utterly foreign to him: Mactaggart’s Galloway is not my Galloway. We are both in perfect agreement, however, that it is a weird and magical place.

And so I would launch this volume with a final toast – a Bladnoch 12-year-old, not a rakiya – to three recipients. First Mactaggart himself. Then Adrian Turpin and the Wigtown Book Festival without whose imagination and support this work would never have been written. Lastly the young people of Dumfries and Galloway, whose love for the place is, as ever it was, constantly in conflict with the need to make a living beyond it. Slainthe. Good Health to all.

A

Anthony Hopkins’ Bench

An isolated bench in Douglas Hall overlooking the Solway Firth occupied at various instances by the Hollywood film stars Brian Cox and Anthony Hopkins. The bench is representative of a syndrome whereby people in the region believe that celebrities are living secretly in their midst, as in, when on one of these wee buses that circle the region relentlessly, some auld heid jerks a nicotined thumb in the direction of a farm track and says something like ‘yon Claudia Schiffer lives doon there’.

Anthony Hopkins’ Bench syndrome emanates from wishful thinking, as well as a kind of pride in Dumfries and Galloway’s insular and highly remote landscape, as though folk with all the world to choose from couldn’t see past sitting in the drizzle at the top of Auchengibbert Hill when they weren’t partying in Monte Carlo or Cannes. Perhaps it’s a folk memory of past glories too, from when the area was a frontier, strategically, economically and culturally important, when everybody who was anybody from Agricola to Walter Scott did indeed walk there.

Although some celebrities do stay in the area – Joanna Lumley has a house in Tynron, Alex Kapranos does yoga in Moniaive (though he’s Scottish so that maybe doesn’t count) – Anthony Hopkins’ Bench syndrome is largely speaking a delusion unsupported by many facts. For every ‘A-lister’ who has lived here there are plenty who have visited and hated the place. Britt Ekland, while filming The Wicker Man, described Newton Stewart as ‘The most dismal place in creation… one of the bleakest places I’ve been to in my life. Gloom and misery oozed out of the furniture.’ Scarlett Johansson’s feelings about being filmed in the moors round Wanlockhead in the middle of November pretending to be an alien harvesting hitchhikers’ body parts are not recorded, but might also be imagined.

Nevertheless the legend and lure of Anthony Hopkins’ Bench continues. Did Brian Cox really stride ashore from a boat and sit on it while taking a break during the filming of The Master of Ballantrae? Did another local spot a holidaying Anthony Hopkins on the same seat? I’m told so, and I’d like to think so too. For every superstar who thinks karaoke in Creetown is not her cup of tea, there must be many a soulful one drawn to the lonely, mythic land and seascape.

See Anwoth, Douglas Fairbanks Junior, Village of the Damned

Anwoth

A small parish near Gatehouse containing a highly atmospheric ruined church which featured in the cult film The Wicker Man. The church itself was that of a very Presbyterian minister, Samuel Rutherford, who in the early 17th century was a highly articulate and well-regarded scholar, though a non-conformist who, career wise, came to a bad end. A very large and rather penile monument dedicated to him is on the hillside above. This place, according to one account a century ago, ‘suggests a humility and reticence that are in keeping with its finest associations’. What an irony therefore that its best known association now is with The Wicker Man, variously described as ‘a barbarous joke, too horrible for pleasure’ (The Sunday Times) and as ‘a beautifully filmed story of primitive sex rituals’ (the Evening News). Is it just one of a whole nest of ironies that the church of this very religious and dogmatic man was used in this most pagan and chaotic of enterprises? In history, mind you, Rutherford fell foul of the prevailing religious orthodoxy and was disgraced in the end. Fell from grace, so to speak. Like his church. Like the film.

I have a fair idea what he would have made of The Wicker Man, with its portable phalluses and its crew’s anarchic occupation of the area for a suitably biblical span of 40 days and 40 nights in the spring of 1973. In the film, the church comprised part of the pagan island of Summerisle, where the failing apple crop called for the sacrifice of a virgin, namely the policeman called Howie, played by Edward Woodward who, while investigating the disappearance of a young girl, was really being set up for a ritualistic slaying. According to the script Howie was meant, for reasons I don’t understand, to be an Episcopalian from the west of Scotland. I had always assumed he was a Wee Free, or certainly some form of extreme Protestant: it enhanced my enjoyment of the burning scene to imagine this.

This religious confusion is just one of the very many anachronisms and mysteries of The Wicker Man which, while portraying a mythic version of Galloway, created as many myths itself, some of which people are still trying to puzzle out. I have laced the film through various entries in this book because in so many ways it seems to sum up some important truths about the region, and its continuing association with the double-headed god of reality and myth, the difficult marriage between what you see and what you believe.

The church played an important and atmospheric part of the film, its ruinous condition being used to demonstrate how far Summerisle had rejected Christianity. In the churchyard Howie finds the missing girl Rowan’s grave. Nearby, a gravestone, a prop specially made for the film, reads, ‘Here lieth Beech Buchanan, protected by the ejaculation of serpents.’ A woman inside the church sits, breastfeeding a new born baby. Rowan’s grave contains only a joke; the body of a hare, the old symbol of death and rebirth. The actress who played the breastfeeding woman, Barbara Rafferty, describes the month on location as one of the most entertaining periods of her life; ‘My daughter Amy and I had a wonderful paid holiday. It was marvellous.’ She had a month’s stay for a 30 second scene because her filming was always being delayed. She thought there was something hugely dodgy about the whole enterprise, ‘everyone did’, but she wasn’t complaining. When her turn came she sat on the gravestone, holding an egg and breastfeeding her child. ‘Edward came in,’ she recalled, ‘and said “Oh my God, what’s happened?” and I had to look a bit witchy.’ I think Edward Woodward could have been playing Samuel Rutherford at that point – or at least I thought that, until I came across a strange account describing Rutherford. ‘His indulgence in erotic imagery when he is dealing with spiritual relations and affections offends modern minds,’ said a minister of the early 20th century. How great. Rutherford as Lord Summerisle. Maybe the giant phallus on the hillside is not so misplaced.

The cottage opposite Anwoth Church, a holiday let, is much in demand for Wicker Man fans, needless to say. The area retains a timeless, unspoilt gloom, enhanced by the tall pine trees enclosing it. In Allan Brown’s Inside the Wicker Man, Edward Woodward is described revisiting the area in 1998 and casually picking up the wooden cross he had made as Howie and discarded during filming, which was still lying in the grass 25 years after it was thrown down.

A suitably gothic postscript occurred when Craig McKay of Castle Douglas cid was called to Anwoth House a few years ago to investigate the finding of a human skull by one of the household’s chocolate Labradors. When he got there, the lady of the house had the skull sitting on the sideboard. ‘It was stained brown, shiny, just sitting there, quite the thing.’ The forensic team was called in and the skull was found to be two centuries old. The labradors had been chasing rabbits, found the skull and came home pleased as punch. A wee investigation revealed a gravedigger had been tidying up some of the graves. ‘I gave it to him,’ said Craig, ‘I think he just poked it back in. I never asked.’

We ask in vain for volunteers to leave this world of doubt and dreams and enter that teetotal land where everything is what it seems

(‘The Promised Land’, JB PICK)

See Anthony Hopkins’ Bench, Village of the Damned

Art

When I worked at Dumfries Academy we used to have an old storeroom where we kept obscure books, piles of mouldering photies, bric-a-brac, all sorts. Very occasionally I used to go in search of some learned tome, Percival’s History of the Sassanid Empire for instance, and tut with irritation at a dirty old canvas of obscure theme which lay underfoot, its glass cracked. Many people stood on this over a period of years, and no one bothered to pick it up. This painting turned out to be Rose Window Cathedral by Sir Robin Philipson rsa, donated to the school and later flogged for more than £35,000 once somebody realised what it was. This episode, which does me no credit at all, does however reveal that I know little about art, though I do later in this book extol the virtues of the magical Chrissie Fergusson. In any case, to overcome my shortcomings on this topic, I have chosen to take the famous Kirkcudbright painter EA Hornel out to the pub for a pint to ask him a series of questions on art rather than make it all up myself.

In the Selkirk Arms EA Hornel is dressed rather fetchingly in a lovat green knickerbocker suit with a long coat and drinking a whisky mac, equal measures of Grouse and Ginger Wine. He is a prepossessing looking man with a disarmingly intense gaze, maybe the result of chronic myopia. He refuses to wear spectacles and carries with him a large magnifying glass in case he needs to read anything more closely.

ME: Edward, let’s cut to the chase. I’ve known lots of artists and a more bitchy crew I’ve never met, apart perhaps from writers. They can’t agree on the colour of piss. They’re pretty mixed about you. What’s been your most important achievement in your working life would you say?

EA: I disagree with the premise. The circle of painters and kindred spirits fostered here in these historic and beautiful surroundings forged friendships that supported and nourished the gifts each one was given. I had friends like Jessie King and Willie Robson and the Fergussons. Of course there are among creative people often tensions.

ME: I like the way Chrissie Fergusson makes Dumfries and Galloway look Mediterranean. It probably didn’t rain as much in your day, did it?

EA: Summer here brought exquisite colours with no parallel in other parts, but when it rained, it rained.

ME: Why did you never marry?

EA: What’s that got to do with the price of cheese? I thought you were going to ask about art?

ME: Okay then, why did you stop experimenting with the controversial but innovative use of patchworks of colour, such as in your work Summer for instance, where the figures seem organically joined with the background, and start instead painting twee pictures of wee lassies rolling about in grass?

EA: The artist wants most of all to present his ideal of vision without regard to tradition, but at the end of the day he also needs to buy the groceries. And people couldn’t get enough of art that showed a romanticised view of the countryside.

ME: You sold out then? At the end were you not photographing wee girls and painting the results? Had it not become a lucrative formula?

EA (exasperated): I turned down a fellowship from the Royal Scottish Academy. I denounced my critics as incompetent to express an opinion about the weather never mind art like mine which celebrates the world in all its glorious garbs. I am a friend of poets, of barefoot travellers who know they will receive here a roof over their heads and the warmth of an open heart.

(He stands up)

ME (also standing): What’s this obsession with wee girls anyway?

EA (reaching for stick): I suppose you think you’re far more revolutionary you smart arse. I bet you’re on expenses.

(A small scuffle ensues)

ME (later, seated, breathing heavily): If you’d been alive what would you have made of the public art in the region, say Andy Goldsworthy’s Striding Arches or Matt Baker’s work in New Luce or the various installations done by, among others, the Stove initiative in Creetown?

EA (perfectly composed): Art above all is there to give a message in a unique and challenging way. But I also detect in these enterprises an attempt to contextualise, to present a work which speaks not just of the artist but of time and place and even community. I find it interesting. Last time my driver Sam Henderson took me to the villages round about here I found them sadly changed. My art set out to glorify the landscape. These pieces seem wistful, like a commemoration, and in some ways are carrying on a long tradition of trading on a lost landscape. But art carries on as an expression of the sublime, in many forms. Do you know that Pink Floyd’s co-manager Andrew King lives here in Kirkcudbright and has all the Pink Floyd album covers on his wall? Now all that mystical lsd-inspired stuff remind me very much of some of my esoteric work, especially the Druids, Bringing in the Mistletoe? Do you know it? One of the druids looks like Syd Barrett.

Actually I think (signalling to barmaid for another round) that the crowning achievement of my later years was in fact my library, which in terms of its accumulation of the rich literature and lore of Dumfries and Galloway was second to none. No one loved Galloway and its inhabitants more than me. Do you need the receipt?

See Chrissie Fergusson, EA Hornel, Midnight in Stavanger, Villages of the Damned

Away with the Fairies

A term, sometimes derogatory, used to describe someone with an unworldly aspect, or lacking in common sense, practicality or logic, as in ‘Don’t ask him, he’s away with the fairies.’

Of course being away with the fairies was once a literal condition in Scotland, and especially in Galloway, one of Scotland’s most fairy-infested parts, and the area of the country where, the legends agree, the fairies held their last strongholds. Infestation is rather a cruel term but it’s certainly true that being away with the fairies was a mixed blessing. George Douglas in his Scottish Fairy and Folk Tales described Annandale as:

the last Border refuge of those beautiful and capricious beings, the fairies. Many old people yet living… continue to tell that in the ancient of days the fairies danced on the hill… Their visits to the earth were periods of joy and mirth to mankind, rather than of sorrow and apprehension. They played on musical instruments of wonderful sweetness and variety of note, spread unexpected feasts, the supernatural flavour of which overpowered on many occasions the religious scruples of the Presbyterian shepherds.

Powerful food indeed to do that. The Corriedale fairies described by Douglas interbred with the locals in a kind of mixed race Brigadoon-like harmony. There are many other stories too of the fairies’ benevolence to humans, especially in return for kindness. When the Knight of Myrton, Sir Godfrey McCulloch, received a visit from the King of the Fairies complaining that a sewer he was having built was undermining the fairy kingdom, he immediately diverted it. This was a good move because the King of the Fairies turned up at Godfrey’s execution in Edinburgh and spirited him away just before the axe.

Many other sources show the fairies’ dark side, however. The beautiful fairy girl of Cairnywellan Head near Port Logan, for instance, was a rose-complexioned 12 year old who could be seen dancing and singing wildly when fugitives of the Irish rebellion of 1798 were found in the Rhinns and summarily shot or hung by the militia. She disappeared for 50 years but couldn’t contain her glee when the Potato Famine broke out and was soon out in the hills, again, dancing to celebrate the mounting body count. The story of the fairy boy of Borgue can be found in the records of the Kirk Session there. This boy would disappear for days or weeks on end, saying he had been with his ‘people’. His grandfather sought help from a priest who banished the fairies. Thereafter the boy was shunned in the community, not because he’d been away with the fairies but because he’d got the help of a Catholic. Trust Dumfries and Galloway to have the only anti-Catholic fairy stories.

Fairy abduction is a classic theme. It’s only too easy to believe that the child who’s just posted all your credit cards through the neighbours’ letter boxes is not in fact yours at all, but a changeling, and that if only you could get your mild-mannered one back things would be okay. Changeling stories range all over the region. Unattended cradles and neglectful nannies were opportunities for the fairies to abduct children and leave in their place spiteful and weird counterparts that you really wouldn’t want to show off to your friends. Unlike your real children, however, you could get rid of changelings in a variety of ways, for instance riddling them with rowan smoke until they disappear up the chimney, as happened to Tammy McKendrick in Kirkinner. Rowan of course is a tree that wards off evil, the reason you see so many planted in sacred spots or churchyards. My mother used to make rowan jelly and feed it to people she didn’t like but I’m not sure they went away any quicker.

Adults also disappeared, sometimes voluntarily, sometimes as a dare or punishment. Thomas the Rhymer, stories of whom are found right across the Scottish Borders, went partly out of curiosity and partly because he was asked by a very alluring woman:

A lady that was brisk and bold, Come riding o’er the ferny brae. Her skirt was of the grass-green silk, Her mantle of the velvet fine;

At every lock of her horse’s mane, Hung fifty silver bells and nine.`

(‘The Ballad of Thomas the Rhymer’, 18th century Scots ballad)

At the Cove of the Grennan near Luce Bay, sailors used to throw bread ashore for the fairies to ensure a good voyage round the Mull of Galloway. There was a fairy cave which led by a narrow passage all the way through to Clonyard Bay on the west coast. Everyone avoided it but one day a piper was dared to explore it. He strode in with his dog. The sound of the pipes echoed deeper and deeper then stopped. The dog, traumatised and completely bald, finally emerged from the cave at Clonyard Bay but the piper was never seen again. It is said, of course, that on windless nights you can still hear the faint sound of the pipes, which is not unlikely really given the number of pipers and pipe bands in the area. But why just on windless nights? In my experience a good piper can cut through a gale.

As is explained elsewhere in this book, Galloway was the last stronghold of the ancient folk, leaving from Burrowhead, though their influence long remained. In A Forgotten Heritage, Hannah Aitken quotes Galloway roadmen who in 1850 refused to cut down an ancient thorn tree to widen the road between Glenluce and Newton Stewart because it was ‘fairy property’. The tree stood for a further 70 years. Nevertheless the fairies were victims, no less than other endemic species, of agricultural improvements, their green habitats ploughed over, the land preached over by successions of Calvinist ministers, no matter how the fairies occasionally subverted the message.

It’s a sad world without fairies, but are they really gone? Very recently I was in a public house in the centre of the region. I was meeting and interviewing a man who said he had been abducted by aliens. I like the idea of beings from outer space and really want them to exist but am sceptical about tales of abduction, which can often be excuses for other kinds of behaviour. A wee bit like thinking your badly brought up kids are changelings. I was struck, for instance, when looking at the so-called ‘Falkirk Triangle’ tales of the 1990s how often the abductees are men coming home late from the pub:

Lorrayne

before you hit me with that object

shaped like a toblerone

let me explain.

We only went for a half pint and a whisky

then set off home but somehow

lost two hours on a thirty minute journey.

My mind’s a blank

but Brian clearly saw

Aliens with black eyes and no lips

leading us onto a kind of craft.

I tried to lash out, explain that I was late,

but they used some kind of numbing ray on me:

it put me in this state.

Lorrayne, don’t you see what it explains?

All the times I crawled home with odd abrasions.

Put that down Lorrayne,

don’t you see I have to go again,

for the sake of future generations?

(‘The X-Files Bonnybridge’)

As far as I know the man I was talking to is the only such abductee in Dumfries and Galloway although the area is an extremely fertile one for sightings of alien spacecraft or UFOS. He insisted on anonymity but told me he had been taken from his home and returned several days later after various procedures had been made under some form of painless anaesthetic. He seemed to have been away for days he said, but when he was returned home he found no time had passed at all. If it hadn’t been for the painless anaesthetic, it all sounded very much to me like a visit to the dentists. However, the procedures were described in detail, though I am not allowed to annotate them here, and he seemed quite sincere, though nervous in the telling of his story. The aliens he said were ‘small and big eyed’. Time, he said, ‘seemed to be suspended’. He couldn’t tell ‘if they were good or bad’. He was returned ‘unharmed’.

When he left, and I was finishing my pint, the bar owner beckoned me over and said, ‘He’s away wi the fairies, by the way.’ Of course, he was. Small people, morally ambivalent, time standing still; the echoes are obvious. It’s as though, having mastered our geography to such an extent that we can’t believe the fairies could share the same physical space as us, we’ve had to re-invent them in outer space.

Having said that I’ve met several folk in my travels who’ll swear to having seen fairies, though most are talking about many years ago. An exception is Scott Maxwell, dyker and travelling folk singer, who swears he was taken in the back of a van once to a fairy pool up in the hills near Moffat: ‘It was two lassies, like. They wouldn’t let me see where I was going, but when I got there it was like nothing I’d ever seen. Moving lights, like the sun in the water really bright, really brilliant but it was a dull day. There was something there, I cannae explain it, still cannae explain it.’

See Mull of Galloway, Myrton and Monreith Bay, Unrequited Love and Guilt, Pine Martens, Things that Go Blink in the Night

B

Badges

The palm trees of Whithorn are bending in the wind. Debbie Mcclymont, curator of the Whithorn Priory like her father before her, and part-time barmaid of the Railway Inn, has just been on the phone to Historic Scotland. ‘That big oak was making some noise last night. There were two trees once, a beech and an oak. They said the beech would never come down and it did. That oak’s right over the house, could kill us all.’ She seems relatively cheerful about it, and loves living in the old 16th century schoolhouse that overlooks the ancient site. ‘When I was young my friends would wait for me in the street, they were scared to come through the dark. It never bothered me, it’s a privilege living there.’

The priory is closed in the winter, hence the bar job. ‘Whole town runs on tourism, really. We get a lot of folk here on pilgrimage. Not this time of year, of course, so it’s all shut up. Ninian’s Cave brings a lot of people, some walk from Mochrum or from further in easy stages.’ Ninian, our native saint but not our patron saint, has been a magnet for a lot of people here over the ages; Scottish royals in need of forgiveness like Bruce and James iv and plenty more humble people too.

Later at the Isle of Whithorn I’m overhearing a group of young folk, visitors like myself, but not so very humble. They’re talking about the forthcoming referendum on Scottish independence, a subject close to my heart. They’ve seen the large blue badge on my bag and are loudly predicting that they’ll need passports to cross the border soon. I bury myself in a pint of Guinness. This part of Galloway has always played host to waves of immigrants and invaders and only one set has ever been required to produce passports. In 1427 James I issued a safe conduct for English pilgrims to Whithorn and the religious sites round about on the condition that they talk about absolutely nothing except devotional topics, wear one badge on their way to Whithorn and one on the way back to the boat and leave no later than 15 days after they arrive. James hated the English and loved badges in equal measure actually: he personally spent 13 shillings on religious badges between the years 1504–5.

I inadvertently catch an eye.

‘Will we need a passport?’

‘How long have you been visiting?’ I ask, pleasantly.

‘A fortnight’, a gentleman in plus fours says.

‘Tomorrow would be your last day then’, I say, adding hurriedly, ‘if this was the time of James i’.

See Ritual Roads

Bank Managers, SR Crockett and the British Union of Fascist Lifeguards

If you don’t count the intelligence services, I have only been in trouble with the authorities twice. Once when I was a boy and my next door neighbour shot an elderly woman in the bottom from my skylight window as she was weeding her flower bed, and another time when I wrote a rather intemperate letter to my bank manager accusing him of being ‘rat faced’ and a ‘Nazi’ when he refused me an extension to my overdraft facility. He did not object to being called rat faced – how could he? The evidence was there for everyone to see – but he did take exception to being called a Nazi. He was in fact a pillar of the village near Dalbeattie where he lived, a Rotarian, active in his local Conservative Party, a member of the golf club and not a Nazi at all. Of course, I apologised.

It is a fact, however, that the biggest branch in Scotland of the British Union of Fascists was in Dalbeattie and was led by the son of a local bank manager, James Little, who was Town Clerk. They had more than 400 members in the town and the countryside round about. Dumfries had 120 members and the area was described in the buf’s newspaper as the ‘cradle of fascism in Scotland’.

The Galloway News of 14 April 1934 describes a meeting held in Dumfries by Oswald Mosley: Great interest was taken in the visit to Dumfries last Friday night of Sir Oswald Mosley, the leader of the British Union of Fascists and a brilliant orator. The demonstration held in the Drill Hall was attended by over three thousand people and although efforts were made by Communists to hold up the meeting by organised interruptions they were effectively dealt with by the large body of Blackshirts who attended as stewards. There were several lively melees when interrupters were forcibly ejected and two of the stewards received injuries.

Why did fascism catch on in Dumfries and Galloway? Almost certainly because the area was, still is, deeply conservative.

Conservatism doesn’t equate with fascism of course but it provided fertile ground for the highly patriotic and romantic delusions of early British fascism. Alistair Livingston, a political blogger and analyst who lives in Castle Douglas notes:

From 1931 until 1997, when the SNP won in Galloway and Labour in Dumfriesshire, the region was solidly Conservative – apart from a narrow SNP win in Galloway in October 1974 which was reversed by the Tories in the next election.

In his blog, Livingstone describes a dinner given on 28 September 1906 in SR Crockett’s honour in Dalbeattie:

Amongst those attending was ‘Councillor Jack’ of Dalbeattie whose son was later to become a buf member and James Little, whose son was to become leader of the local fascists.

After toasts to ‘The King’ and ‘The Imperial Forces’, Major Gilbert McMicking, Liberal mp for Kirkcudbrightshire and then Galloway from 1906–1922, made a long speech in which he emphasised that:

the health and vitality of the Empire would increasingly rely on the health and vitality of Britain’s rural rather than urban population. Mosley’s meeting in Dumfries was likewise peppered with references to agriculture and the land. This mystical attachment, symbiosis, between society and the rural is evident in Nazi theories. Only through a re-integration of humanity into the whole of nature