7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

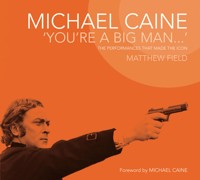

He defined an era and still helps define a nation, Michael Caine is a cult figure, an icon and a cinematic heavyweight, who has given some of the greatest big-screen performances on either side of the Atlantic. This book is a celebration, documentation, and fascinating insight into the performances that made that icon - the story behind the roles, the reactions, the influences, and - in some cases - the backlash, plus quotes from the man himself on his performances and from those he worked with. Caine has made over 80 films in his career, and all are covered here, from the early British successes of Zulu, The Italian Job, and his hugely influential gangster portrayal in Get Carter through the maturity of Hannah and her Sisters, the doomed stinkers such as The Swarm and back to his best with Cider House Rules and The Quiet American. Author Matthew Field, who has interviewed Caine, shows his enthusiasm and detailed research of the actor's work in a book that is not only for the fans of the man himself, but for those with a love of cinema and the craft of acting itself.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 183

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

MICHAEL CAINE

‘YOU’RE A BIG MAN…’

For Philippa, thank you for your patience, love, and encouragement.

MICHAEL CAINE

‘YOU’RE A BIG MAN…’

THE PERFORMANCES THAT MADE THE ICON

MATTHEW FIELD

Contents

Introduction: Citizen Caine

Early Days

Early Days Filmography

The 1960s: Zulu to The Battle of Britain

The 1970s: The Last Valley to Beyond the Poseidon Adventure

The 1980s: The Island to Dirty Rotten Scoundrels

The 1990s: Bullseye! to Cider House Rules

The new millennium: Quills to The Actors

And the rest…

The Awards

Bibliography

Index

Foreword by Michael Caine

So this is what I’ve been doing for the last forty-five years.’

It’s a surprise and a delight for me to have this book because it is a chronicle of what I’ve been doing rather than a biography, which, after all, is only the opinion and view of a single man. But this book lets you, the reader, make up your mind about what I am and what the hell I’ve been up to all this time.

Although I have photos of myself at 6 months, 6 years, 11 years and 18 years, it’s not a great photographic chronicle of my early life. This book, with its excellent choice of photos, shows that I’ve more than made up for that shortfall.

Matthew’s research is excellent and if you’re at all interested in me or my career, then I recommend this book wholeheartedly. It’s fair comment, which is unusual in my professional life.

25th August 2003

Introduction

Citizen Caine

First of all I choose the great roles, and if none of those come, I choose the mediocre ones, and if none of those come, I choose the ones that pay the rent

From Palmer to Powers, from Italy to Newcastle, the former Maurice Micklewhite has become the London lad done good. As Barry Norman once suggested: if you add it up, maybe only one in seven of Michael Caine’s hundred-odd films is actually worth seeing, yet he has become one of the world’s best-loved movie stars. Productivity rather than quality is Caine’s motto it would seem, when it comes to his career. He once said, ‘First of all I choose the great roles, and if none of those come, I choose the mediocre ones, and if none of those come, I choose the ones that pay the rent.’

Born Maurice Joseph Micklewhite in March 1933 in South London, it was after undergoing his National Service in Korea in 1952 that he decided he wanted to pursue a career in acting. Changing his name to Michael Scott, he was told by his agent that Equity already had an actor by that name on their books, and was forced to change it for a second time. Gazing up at the billboard in London’s Leicester Square for the film The Caine Mutiny his mind was made up: Michael Caine.

Caine is perhaps the best-loved and most popular British actor in the world, becoming one of Britain’s few memorable international movie stars. Many told him he could never be an actor because he didn’t talk posh. His reaction was: ‘I’ll show them how to be an actor without talking posh … and I did!’ But it wasn’t until the age of 30, and after spending years as a struggling actor, that Caine hit the big time.

Zulu transformed Caine into a movie star. It was a film packed with spectacle: stunning photography, brilliant editing and a spine-tingling soundtrack. It embraced the kind of heroism that would stir the blood of generations after it.

With the mighty success of Zulu behind him, James Bond producer Harry Saltzman gave Caine the lead in The Ipcress File: secret agent Harry Palmer, a character who was the complete antithesis of 007. Caine even insisted on wearing his black hornrimmed glasses for the part, claiming ‘… no leading man had worn glasses in a film since Harold Lloyd!’

Alfie is one of the most talked about films of the 1960s. The frank discussion of pre-marital sex and adultery combined with the chirpy cockney banter may seem a little dated now, but Caine as the womanizing lothario must rank as one of his strongest performances of all. Caine was nominated for his first Academy Award for the movie, but lost out to Paul Scofield in A Man For All Seasons. Alfie was the swinging Sixties on film, and Caine’s cockney accent is showcased with no apologies, something he is proud about, although he feels he has been patronized by the British press. He said ‘I’m every bourgeois nightmare: a cockney with intelligence and a million dollars.’

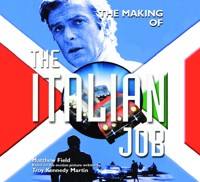

After a spate of forgettable movies Caine left the Sixties in style as Charlie Croker in Peter Collinson’s The Italian Job. This piece of patriotic cinema, told in a typically Sixties jingoistic fashion, benefited from a fantastic array of cameo performers from such comedians as Benny Hill and Fred Emney. But it was the appearance of three Mini Coopers in a fender-bending car chase through the streets and arcades of Turin that stole the show from Caine. ‘It was the greatest advert for the Mini the world has ever seen,’ he comments. The fact that Hollywood has recently remade The Italian Job does nothing but beg the question ‘Why?’

Michael Caine was a British icon by the Seventies. After appearing in the all-star cast of The Battle of Britain, Caine portrayed Jack Carter in the Mike Hodges’ film Get Carter, a film that sealed his reputation as the number one gangster in British cinema. It was this movie that became the genesis of the gangster genre, the film that spawned Lock Stock and Snatch et al.

Throughout the Sixties Caine lived the life of a playboy. He shared a flat with Terence Stamp, and they indulged themselves in a world of fast cars, fashion and girls. But in 1972 he spotted the love of his life in a television commercial for Maxwell House coffee. Shakira Baksh became Mrs Caine in Las Vegas: ‘It was like one of those weddings you see in a corny movie. My agent gave the bride away and paid for the wedding. It was only $174.’

Not long after finishing Get Carter, Caine was faced with what is arguably his most challenging role to date – Sleuth, in which he appeared opposite Laurence Olivier. ‘I realise I have a partner,’ commented a shrewd Olivier just weeks into filming. Both actors were nominated for an Oscar for best actor, but neither walked away with the coveted award, which instead went to Marlon Brando for The Godfather.

In 1975 Caine made his favourite movie of all time The Man Who Would Be King, in which he starred opposite his old chum Sean Connery. For both actors, making the film was one of their most enjoyable experiences of all time. The Man Who Would Be King, directed by John Huston, even found room for a cameo performance for Caine’s wife Shakira.

In the mid-Seventies Caine decided it was time to quit England. Fed up with the amount he was paying in taxes he became a tax exile in California. He was vocal in his irritation, claiming he was being penalized for his own success. He later said that his talent was appreciated more in the States: ‘In America I’m treated as a skilled movie actor. Here I’m a cockney yobbo who was in the right place at the right time.’

Upon his arrival across the Atlantic, he indulged in a string of big-budget disaster movies. The Swarm, Beyond The Poseidon Adventure and Ashanti were disasters in every sense of the word.

After this period of poor-quality films, Educating Rita was firm evidence of Caine’s acting ability. It was just so completely different from anything he had ever done before. Putting on two stone in weight and growing a face full of hair, Caine hobbled around the streets of Dublin as a drunk university professor of English Literature, as he reluctantly taught Julie Walters the finer points of poetry and Shakespeare. Caine’s performance earned him yet another Oscar nomination, but once again the gold-plated statue eluded him.

After Educating Rita the gems seemed to dry up, although one small movie entitled Deathtrap, in which Caine co-starred with Christopher Reeve, did test his limits as an actor. A series of disasters ensued: Blame It On Rio, The Honorary Consul and Water. Some suggested that his time was up. One British columnist commented that he was corny and clichéd and had ‘…been coasting along on a very small talent for a very long time’. But he was still commanding big money, and was one of only a handful of Brits who had the respect of the major Hollywood studios, and his first Oscar was just around the corner.

By the mid-Eighties the razzmatazz of Hollywood had lost its savour for Caine and he returned to England with his family.

Hannah And Her Sisters was by no means as good a role as Educating Rita, but it did give him the opportunity to work with the great Woody Allen. This collaboration brought that most coveted prize: an Oscar (for Best Supporting Actor). With the Oscar firmly in his hands he said, ‘This little fellow is the big one. It’s another dream come true.’ But every silver lining has a cloud, and Caine confessed that he was a little disappointed, ‘I’d rather have won it for Educating Rita – I really thought I was going to win that one.’

After he had finally won the Oscar he made another run of nonsense: Without A Clue, The Fourth Protocol and one of his most famous stinkers of all time, Jaws: The Revenge. He was offered a tremendous fee and he took the job. One film that stood out among the dross was Mona Lisa, which required Caine to slip on his gangster shoes once more as he performed a cameo role as a hard-nut killer opposite Bob Hoskins. Caine claims he had never been so sure about a part before or since.

Caine had always had a hankering to direct but in 1988 admitted that maybe that fad had passed: ‘I have reached that stage that if I have any spare time I like to fill it at the Hotel du Cap in the south of France or somewhere. So the thought of getting up at 6 in the morning to direct a load of buggers like me is not as attractive as it was.’

In 1988 the wonderful Dirty Rotten Scoundrels appeared. He starred opposite Steve Martin, with the duo playing a couple of crooks working on the French Riviera. However, this was again followed by a string of disasters, including Michael Winner’s Bullseye! with Roger Moore. Yet at Christmas 1992 Caine reappeared in a role that was both a surprise and a treat. Playing Ebenezer Scrooge opposite Miss Piggy in The Muppet Christmas Carol, Caine gave his best performance for years and visibly enjoyed the whole filmmaking process.

For a while, during the early Nineties, Caine took a break from the game. His dissatisfaction with making movies left him time to write his autobiography. He also used the hiatus to open a string of restaurants. He had for some time had a share in the famous Langans, the ‘in’ place in London’s Mayfair, and knew his wines as well as he knew his scripts.

‘I’ve made a lot of crap and a lot of money, which means I can afford to be artistic now,’ he said after completing a small picture entitled Little Voice in 1998. After several years out of the game Michael Caine came back with a bang. Little Voice was blessed with the wonderful British cast of Ewan MacGregor, Jane Horrocks, Brenda Blethyn and Jim Broadbent, and was the first of a string of good movies and great roles for Caine. He was on a roll.

With the lad-magazine boom of the Nineties, Caine’s iconic status was reborn. He was increasingly popular with the new generation of young British men, who found much to admire in the lothario Alfie, the crime mastermind in The Italian Job and the gangster of Get Carter. As Get Carter inspired a new wave of popular, successful Brit-flick gangster movies, a fresh generation of British youth discovered a young Michael Caine.

The good roles kept coming and his next choice was to be one of his best yet: Dr Larch in The Cider House Rules (1999). ‘He is probably the nicest and gentlest person I have ever played,’ said Caine shortly after the film was released. Set in the Thirties, The Cider House Rules was the passionate story of a doctor’s work at an orphanage in New England. It was the movie that earned him his second Oscar.

With the acceptance of his second Academy Award Caine was more in vogue than ever. ‘This last Oscar was much more important than the first, because I’d been away. And neither of them were for playing cockneys’, he said. But it would turn out to be a double whammy, as on his return to the UK just weeks later, he was presented with Britain’s highest accolade, the BAFTA Fellowship award. But nobody was prepared for the ear-bashing rant that was to follow, as he stood on stage in the confines of the Odeon Leicester Square. He told a shocked audience, ‘I never felt I belonged in my own country, in my profession, I think of myself as a loner. All the way through I have felt on the outside as though I was trying to make something for myself with very little help.’ Some critics didn’t care for Caine’s tirade, one even stating, ‘Poor old Michael Caine, multi-millionaire, Oscar winner, businessman, country estate in Britain, married to one of the world’s most beautiful women, and still he’s bitter.’

But maybe just someone was listening. In November 2000 he went into Buckingham Palace and emerged as Sir Michael Caine.

Caine burst into the 21st century with an array of splendid roles ranging across the genres: from gangster pictures like Shiner to Hollywood comedy Miss Congeniality and a retro role in Austin Powers in Goldmember. Michael Caine was back.

Caine sums up his career spanning a huge 50 years in one simple statement: ‘Usually you have to die to become an icon. I just got there early.’

Matthew Field

April 2003

Early Days

Maurice Micklewhite dreamed of being in the movies while growing up on the poor streets of the Elephant and Castle in London. Leaving school at the age of 15, he found work as a messenger boy on Wardour Street, working for the J Arthur Rank Organisation. But this early flirtation with the movie world was short-lived when he was sacked for smoking in the toilets.

Called up for military service in Korea at the age of 18, he returned home two years later hoping to begin a career in acting, unwilling to follow in his father’s footsteps slumming it as a porter in the Billingsgate fish market. ‘It was in Korea that I noticed heroes weren’t always six feet three with perfectly capped teeth, but ordinary guys,’ he said.

Called a sissy and a ‘nancy’ by those back in the Elephant, he roamed around London’s West End with a copy of The Stage wedged under his arm in the hope that somebody would notice him. Changing his name to Michael Scott, he fought for work as a TV extra, before going into repertory where he appeared in over 80 plays.

In 1956 he landed his first role in a feature film. A Hill In Korea starred Stanley Baker. It was a minor role; in fact it was so minor he didn’t even receive a credit. The director, Julian Amyes, gave the young hopeful the part of a soldier with four lines. ‘I regarded Michael as a very competent young actor,’ he recalls. Others disagreed. On seeing the movie his agent, Jimmy Fraser, dropped him from his books. The reason? He didn’t like his blonde eyelashes.

Having been told by Equity that there was already an actor called Michael Scott he needed to find a new professional name. After being inspired by the poster for a new movie of the time, The Caine Mutiny, he chose the name that would become famous. After continuing to take small ‘blink-and-you-miss-him’ parts, he finally received his first screen credit in Nigel Patrick’s How To Marry A Rich Uncle in 1957.

Zulu was still a long way off. He struggled his way through the late Fifties taking brief roles whenever and wherever he could get them. He continued to make fleeting appearances in such movies as DangerWithin, The Key, Passport To Shame and Foxhole In Cairo. In Solo For Sparrow he played an Irish gangster, but on the first day the producer heard Caine’s attempt at an Irish accent and wouldn’t let him say another line in the film.

The television play The Compartment (1963) was unwittingly tailor-made for Caine: the story of two men in a railway carriage, one a middle-class snob, the other, as Caine puts it, ‘a vulgar cockney’. In fact, agent Dennis Selinger placed Caine on his books simply on the strength of this one performance. Shortly after the screening of the play, Caine was stopped by Roger Moore as he walked down Piccadilly. Moore, who by 1962 had become famous as The Saint, stopped Caine to shake his hand and congratulate him on his performance.

Then there was Zulu. The rest, as they say, is history. He had certainly deserved the break, after more than 150 television plays and over 10 years as a penniless struggling actor. During those early difficult days, Michael had said to himself, ‘Michael, you’re never going to become a star. You’ve not got much personality. So what you’ve got to do is learn how to act.’ He did become a star, with a strong personality, and demonstrated repeatedly the quality of his talent.

Early Filmography

Sailor Beware

1956

A Hill In Korea

1956

How To Murder A Rich Uncle

1957

The Steel Bayonet

1957

Carve Her Name With Pride

1958

The Key

1958

The Two-Headed Spy

1958

Passport To Shame

1958

Danger Within

1958

The Bulldog Breed

1960

Foxhole In Cairo

1960

The Day The Earth Caught Fire

1961

The Wrong Arm Of The Law

1962

Solo For Sparrow

1962

Note that all the films in this book are ordered by the year of their release and NOT by the year of production.

Zulu

(1964)

War drama UK Colour 138 mins Stanley Baker, Michael Caine, Jack Hawkins, Ulla Jacobsson James Booth

Director: Cy Endfield

Producers: Stanley Baker/Cy Endfield

Screenplay: John Prebble and Cy Endfield

He painstakingly researched the life of the real Bromhead, who had been short, dark and partially deaf

For Michael Caine, Zulu was a long time coming, but when it did, his career and life hit the fast lane.

Cy Endfield’s superb re-creation of the 1879 battle at Rorke’s Drift provided a stunning star-making performance for Caine. But it was only by chance that the then ‘jobbing’ actor landed the role of Gonville Bromhead opposite the legendary Stanley Baker, who also acted as the film’s producer. ‘You don’t look like a cockney to me. You look more like an officer. Can you do an officer’s accent?’ asked Cy. Caine could do anything, and immediately screen-tested for the role of the foppish lieutenant. He landed the part on the eve of his 30th birthday, the date Caine vowed he would give up acting unless he found a break. Bumping into the actor at a party, Endfield told Caine, ‘It was the worst screen test I’ve ever seen, but you got the part … don’t ask me why.’ Caine later found out that there was no time to find anyone else, and within days an entire production unit flew out to South Africa to begin work on one of Michael Caine’s most famous performances of all time. Once Caine had been offered the part of the lieutenant, he painstakingly researched the life of the real Bromhead, who had been short, dark and partially deaf. Michael persuaded both Baker and Endfield to allow him to show hidden strength in the character, who, in the script, appeared merely as an ineffectual Victorian officer. He suggested that if the character were to be more complex it would reflect better on Baker’s character John Chard.

Much of the film’s joy comes from the stunning photography of the battle scenes and the Zulus en masse. The sequences of the Zulus thundering over the mountain are truly spectacular. Add to that the bright red tunics and white helmets of the Royal Engineers against a backdrop of blue skies and the scenery of Rorke’s Drift and you can see why the film still thrills to this day. John Barry’s haunting soundtrack and Richard Burton’s narration were the icing on the cake. But filmmaking was a new experience for the Zulus: the African extras had never seen a film before, let alone acted in one. The real Zulu leader Chief Buthelesi was even playing Chief Cetewayo in the film. To give the Zulus a taste of Hollywood, Baker’s crew painted a gigantic rock white, which became the screen for nightly projected performances of Buster Keaton and Laurel and Hardy, shown to a bemused 4,000-strong crowd.