20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

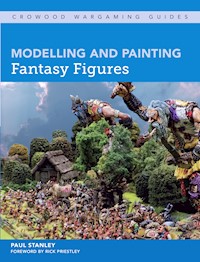

A wide array of fantasy miniatures is available to wargamers and modellers, manufactured from an increasing number of different materials each with their own unique modelling challenges. From the multipart hard plastic 28mm miniature to the metal and resin models common in all other scales, this book provides wargamers with a wealth of information to achieve the best results. It discusses issues of scale with fantasy miniatures; demonstrates a variety of modelling and painting techniques at different scales; provides step-by-step guidance on building, converting, repairing and painting figures; explains dry brushing techniques, the three colour method, multilayering and shading with washes and, finally, it considers basic techniques and maintaining the compatibility of miniatures between different gaming systems. Whether modelling single figures, a handful of warriors for a warband or tackling a huge army for a mass battle game, there is something for every fantasy figure modeller, collector or gamer. Discusses issues of scale with fantasy miniatures. Demonstrates a variety of modelling and painting techniques at different scales. Provides step-by-step guidance on building, converting, repairing and painting figures Lavishly illustrated with 274 colour photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

MODELLING AND PAINTING

Fantasy Figures

PAUL STANLEY

FOREWORD BY RICK PRIESTLEY

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2018 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2019

© Paul Stanley 2018

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 496 4

CONTENTS

Foreword

Preface

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 CHOOSING YOUR MINIATURES

CHAPTER 2 TOOLS, EQUIPMENT AND MODELLING MATERIALS

CHAPTER 3 MINIATURE OVERVIEW

CHAPTER 4 ASSEMBLING MINIATURES

CHAPTER 5 CONVERTING AND REPAIRING MINIATURES

CHAPTER 6 BASIC FIGURE PAINTING TECHNIQUES

CHAPTER 7 PAINTING SKIN TONES AND FACIAL FEATURES

CHAPTER 8 PAINTING CLOTHING AND ARMOUR

CHAPTER 9 PAINTING CREATURES AND MONSTERS

CHAPTER 10 PAINTING WEAPONS AND ACCESSORIES

CHAPTER 11 BASING MINIATURES

List of Contributors

Bibliography and Suggested Reading

Index

Foreword

WELL, HERE WE HAVE a rare thing: a new, comprehensive and beautifully presented book just for us gamers, collectors and painters of fantasy models. Rare enough in itself, I think you’ll agree, but rarer still to find such a font of wisdom and useful information packed between the covers of a first volume from a new author – Paul Stanley.

Today the hobby of fantasy wargaming draws inspiration from every imaginable kind of media, from classic literature to the most recent hi-tech movie extravaganzas and colourful made-for-TV epics. In recent years the number and variety of fantasy games has grown and proliferated with the advent of universally accessible technology and the all-pervading world-wide web. As a result, your typical fantasy wargamer of today is also likely to be a fan of video games such as ‘World of Warcraft’ or one of the many similar games inspired by on-line role play.

One might imagine that all these entertainments would render obsolete the more traditional kind of role-playing and tabletop games conducted with model soldiers and fought over carefully modelled terrain – but not a bit of it! If anything, fantasy wargaming with models is even more popular than ever, and not despite all those TV shows, movies and video games, but to a large extent because of them!

Today we wargamers and modellers of the fantastical are surely spoiled for choice when it comes to the range of subjects available for our consideration. Whatever our taste might run to, someone, somewhere, will make it – and probably several someones at that! The quality of modern acrylic paints and advanced sculpting materials such as epoxy putties and easy-to-use polymer clays, means that our hobby is now, more than ever, accessible to everyone. It is hard to credit that models were ever hand carved from tin, or that accessories such as swords and guns had once to be painstakingly soldered in place or carefully cut and shaped from sheet metal.

The recent development of 3D sculpting tools has brought forth a new generation of technically savvy sculptors and digital modellers to add to the mix. Yet as we see in these pages, these developments have all added to, rather than replaced, traditional skills, so that modelling now encompasses computer-aided design just as much as the tried and tested methods of yore.

This useful, informative and eminently practical book is without doubt the ideal introduction to the contemporary world of collecting, painting and converting models for fantasy wargaming. It is also an endlessly useful work of reference, and a source of practical ideas for experienced hobbyists ready to tackle more demanding subjects or to extend their existing skills. Even the most experienced painter and modeller will find much that is thought provoking and inspiring within these pages. Especially pleasing are the many artfully rendered photographs with which this book is copiously and colourfully illustrated.

The carefully prepared step-by-step painting guides are clearly presented and the results shown are fully achievable with a modicum of patience. Nothing is taken for granted, with chapters devoted to the correct assembly and preparation of models, converting or modifying, and the all-important matter of modelling bases for that perfect finish! Whilst due attention is given to the matter of readying our troops for battle, monstrous creatures are also considered in appropriate detail and such subjects as architectural pieces, machines and artefacts are dealt with in a helpful and effective fashion.

So what are you waiting for? Read on! And let us hope that our book is soon joined by many more from Paul and from a series that will surely become an indispensable addition to every wargamer’s bookshelf.

RICK PRIESTLEY

Preface

IF, LIKE ME, YOU were a young boy growing up in the late 1970s, in a time before gaming consoles and twenty-four-hour television, most of your evenings and weekends were probably spent building plastic kits or playing with toy soldiers. Although my initial forays into wargaming involved launching marbles at 1:35th scale plastic figures manning purpose-built Lego fortifications, it wasn’t long before I realized that if I was going to paint these soldiers, I would need to find a less brutal way of gaming with them. The chance discovery of a copy of Practical Wargaming by C. F. Wesencraft in the local library heralded a sea change in my approach to miniature modelling as I began to appreciate how strategic battles could be fought without harm to lavishly painted soldiers, lovingly arranged on a tabletop filled with terrain.

With the dawn of a new decade and my arrival at a new school came an introduction to 25mm fantasy modelling and games such as ‘Advanced Dungeons and Dragons’ and ‘Warhammer Fantasy Battles’. My new-found friends and I started collecting white metal models from Ral Partha, Grenadier and Citadel Miniatures in order to populate the role-playing games and fantasy worlds we were creating. The school playground became a busy arena in which we exchanged hints and tips on painting techniques and traded our unwanted miniatures. As we huddled around early copies of White Dwarf magazine, people such as Gary Gygax, Rick Priestley, Bryan Ansell, Ian Livingstone and the Perry Twins became our heroes, their names passing into gaming legend to join the likes of H. G. Wells and Donald Featherstone.

Practical Wargaming by C. F. Wesencraft showed the young author how strategic battles could be fought without harm to lavishly painted models.

Whilst writing this book I have not only had the privilege of meeting some of my childhood heroes, but I have also been reminded how those early years fired an enthusiasm for miniature modelling that has remained with me to this day. In reading this book I hope that many modellers, young and old, will be inspired to continue with the hobby, in much the same way that others have inspired me.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would particularly like to thank Rick Priestley for his time, his advice, his guidance and generous assistance during the writing of this book. I am also deeply indebted to Bryan, Diane and Marcus Ansell of Wargames Foundry for their generosity in supplying miniatures and paints, and for allowing access to their premises and Bryan’s huge collection of painted models.

I must also thank the following: Andy Lyon (Ainsty Castings), Rob and Alex Huntley (Warploque Miniatures), Paul Reid (Ral Partha Europe), Nick Eyre (North Star Miniatures), Paul Sawyer (Warlord Games), Dave Hoyles (Museum Miniatures), Andrew Taylor (Antediluvian Miniatures), Mark Dixon (CP Models), Richard Novis (Perfect Six), Leon (Pendraken), Peter (Baccus), Jason (Creature Caster), Stu Armstrong (Colonel Bill’s), Anthony Meekings (Debris of War), Adrian (Adrian’s Walls), Simon Cox (S T Cox Terrain), Mick Hoe (Leven Miniatures), Martin and Diane (Warbases), Erik Priessman (Figures In Comfort) and the guys at Fireforge Games, Westfalia Miniatures, Brother Vinni, Castle Miniatures, Secret Weapon Miniatures, Rapier Miniatures, Sarissa-Precision Ltd, Magnetic Displays and 44th Street Ltd for their generosity in supplying products and allowing their use in this publication.

Special thanks are also due to Michael and Alan Perry (Perry Miniatures), who in addition to allowing use of their products have also been very generous with their time.

Kind thanks also go to Steve Dean and David Markes for allowing me to include examples of their work and to Richard (Orclord) Hale for supplying additional photographs from his comprehensive private collection.

In gratitude for their encouragement, friendship and continued support over the years I must thank Grant Jessé, Helen Wallis and Nick ‘The Mighty Kiwi’ Hughes.

Finally I would like to thank the team at The Crowood Press for giving me the opportunity to write this book and for all their support throughout.

The author in the middle of a fantasy wargame with Rick Priestley, writer of many wargaming rules including Warhammer, Warmaster and Black Powder.

INTRODUCTION

DESPITE NUMEROUS PREDICTIONS THAT table-top gaming and miniature modelling would disappear in the wake of increasingly sophisticated computer games, today the hobby not only remains popular but continues to grow. In fact, since it emerged as a popular pastime in the early 1980s, the hobby has become a global industry with an annual turnover measured in hundreds of millions of pounds. Whilst some miniature manufacturers acknowledge the potential sales threat posed by gaming software, it has not been the death knell that many have prophesied, which begs the question, why?

Although the ability to immerse oneself in a first person shooter game, or become the general of a huge virtual army, clearly have their attractions, to write off an entire hobby as a result is to fail to appreciate the true appeal of model making. Those who engage in the hobby do so because they enjoy it. There is something innately satisfying about taking a box of unbuilt parts and from it creating a finished object that is both beautiful and functional.

The development of computer games is not the only threat that miniature modelling has faced and it will not be the last. Those who espouse the virtues of new technology claim that the arrival of the 3D printer will herald the next revolution in the hobby.

Proponents tell us that soon every home will have one and gamers will no longer buy their miniatures, but will instead purchase a licence to print them in whatever scale they desire. Indeed, if they are to be believed, as 3D colour printing becomes more affordable, we will no longer have need of paints. Figure sculpting and miniature painting will become redundant art forms as 3D scanning technology enables us to digitally capture real people wearing military uniforms in a variety of poses. These 3D computer models will then be used to generate entire armies in miniature that require no preparation before gaming.

Comments like these remind me of a discussion I once read on a wargaming forum nearly a decade ago. One very enthusiastic advocate of digital sculpting explained how, with this software, sculptors would no longer need to spend hours smoothing and shaping putty, adding that this would lead to improvements in the quality and quantity of available miniatures, which in turn would be great for the hobby. On reading his remarks I could not help but point out that the time-consuming activity of smoothing and shaping putty is called sculpting and it forms an intrinsic part of what every miniature sculptor does. Ten years later there is still a demand for hand-sculpted miniatures because, as many gamers put it, they have a certain character about them not found in digitally rendered models. In short, there is room for both.

Impending revolution or not, the hobby has seen many changes over the years including the introduction of water-based acrylic paints, the arrival of versatile epoxy putties, the invention of the plastic slotta-base, the use of resin and hard plastic in the production of miniatures, photo-etched brass detailing parts, the development of washes and textured paints, static grass, laser-cut bases and terrain, digitally sculpted models and 3D-printed production masters, to say nothing of the impact that the internet has had in facilitating global sales and the exchange of ideas – and yet the fundamental principles of model making remain the same.

Whilst there are undoubtedly many gamers who are perfectly happy with the idea of purchasing pre-assembled and pre-painted miniatures, for many more the process of building and painting models is just as important as the gaming itself. It is also fair to assume that these modellers find the massed ranks of digitally rendered troops on a computer-generated battlefield to be a poor substitute for the awe-inspiring spectacle of hundreds of beautifully painted miniatures arranged over a gaming table.

Modellers of a certain age, who painted their fantasy miniatures using enamels, will remember how the arrival of modelling acrylics heralded a new era in figure painting. If, like the author, they were also the proud owners of the 1983 Citadel Miniatures Catalogue, they will probably remember Peter Armstrong’s ‘Painting Guide’ and Tony Ackland’s ‘Guide to Basic Figure Conversions’. These two articles, which appeared in the back of the blue catalogue featuring the Citadel Imperial Dragon on its cover (affectionately known as the Chicken Dragon), had a profound effect on the working practices of many modellers.

The awe-inspiring spectacle of hundreds of beautifully painted miniatures arranged over a gaming table is just one of the many reasons the hobby continues to grow.

Prior to the arrival of these guides, a great many miniatures were painted in flat colours in a style similar to Britains Toy Soldiers and as per the simple instructions on boxes of Airfix models. Although admittedly we no longer black-wash fantasy miniatures with thinned enamel or liquid boot polish before priming them, and neither is it common to black line between different colours after painting, the other techniques described among those pages are still in use today.

Those same modellers may also recall how difficult it was to obtain fantasy figures in an era that predates the whole Games Workshop and Citadel Miniatures phenomenon. While Games Workshop, with a lion’s share of the market, has undoubtedly been a driving force behind a number of innovations within the industry, many of the founding members have gone on to do other interesting and noteworthy things, making today one of the most exciting times in which to be involved in the hobby.

In an age where the internet provides even the smallest business with a shop window on the world, and many are taking advantage of kickstarters and crowd funding to finance new ranges, the variety of games and miniatures available to today’s fantasy modeller is astounding. Many of these companies are part-time operations targeting niche markets with boutique miniatures in a way that the larger, profit-hungry manufacturers cannot.

Compared with the early 1980s, the variety of games and miniatures available to today’s fantasy modeller is astounding.

This book casts an eye across a selection of these models as it covers the basic principles in miniature modelling and presents a variety of additional techniques, which may also be of interest to those with more experience. The step-by-step guides offer hints and tips to help modellers achieve great results without labouring for days or even months over a painting table. These processes do not need to be followed to the letter; rather, in the same way that chefs might tweak the recipes in a cookbook to suit their tastes, modellers are encouraged to adapt these techniques to suit their needs. Above all, have fun with your fantasy miniature modelling and don’t be afraid to experiment.

The sheer enjoyment and sense of fulfilment that comes from creating a masterpiece in miniature is one of the many attractions of fantasy figure modelling.

Choosing Your Miniatures

1

THERE ARE MANY REASONS why someone might wish to become involved in fantasy figure modelling, not least of which is the sheer enjoyment and sense of fulfilment that comes from creating a masterpiece in miniature.

The appeal that fantasy modelling has over its historical counterpart is that in principle there are fewer limitations on creativity, other than those of one’s own imagination. This is not to say that the fantasy genre is without boundaries, or that the modeller will not be conforming to certain principles when creating their masterpiece – in the same way that a military modeller is constrained by the type of armour or the colour of the uniforms that were worn by the fighting men and women being depicted in miniature – but the world of fantasy modelling offers far more freedom for interpretation. For many, the addition of creative freedom is a significant attraction.

WHY FANTASY?

Some modellers are drawn to fantasy simply because they have had a fascination for the genre since childhood. Choosing it as the subject matter for their modelling allows them to combine this fascination with a desire to build and paint miniatures. Other miniature modellers are predominantly gamers, and for them the activity of building and painting miniatures is just one aspect of an overriding interest in strategy gaming. Whilst gamers today are presented with a wide variety of fantasy miniatures and fantasy gaming rules, wargamers of the author’s generation are likely to have progressed to fantasy after initially cutting their teeth on historical wargaming. In the case of the author, this was due to an absence of fantasy miniatures in the popular marketplace, and a lack of any noteworthy fantasy rules prior to the early 1980s, while in contrast historical wargaming had by this time grown in popularity and become far more accessible.

It can be surmised, therefore, that fantasy modellers will usually fall into one of two categories: they will either be a miniature modeller first and foremost, with an interest in building and collecting fantasy figures, or they will be a gamer collecting fantasy miniatures with a specific end use in mind. The two are not mutually exclusive, however, and they may indeed be all of the above.

At first glance this may appear to be a trivial point, but the reasons that drive someone to collect fantasy models in the first place are likely to be the same reasons that shape the growth of their collection and ultimately determine which miniatures are most suitable. Given that fantasy miniature modelling is not an inexpensive hobby, it is often wise to choose purchases carefully because, ultimately, a wrong decision can also prove to be a costly one.

THE COLLECTOR

The collector arguably has more scope than most miniature modellers. Purchasing decisions based purely on a desire to build and paint a particular model allow complete freedom of choice, whether that be in terms of the size, the scale or the subject matter of the model, or the manufacturer from whom it is acquired. Where the end purpose is simply the production of a display piece, then whether or not the miniature corresponds in size, scale or theme with any other models in the collection is of little or no consequence. The reward for the collector comes through the process of building, painting and ultimately owning a finished example of the model in question.

A notable exception to this generalization comes when choosing to collect a specific range of models. The miniatures within these ranges might be produced in conjunction with a particular game, film or book, limiting the collector to one manufacturer or models of a uniform size and scale. The collector still retains a significant degree of freedom, however, in determining how these miniatures are displayed, whether that is singly, on individual bases suitable for gaming, or collectively on one large base in the form of a diorama or small vignette that tells a story.

THE GAMER

Collecting fantasy figures with the intention of gaming might be more restrictive, but it is by no means less enjoyable. Indeed a great deal of pleasure can be derived from the challenge of acquiring specific miniatures in order to fulfil the particular requirements of a game, whether that is building a fantasy army for wargaming or collecting a range of character models and monsters that can be used in role playing. The size or scale of the miniatures, together with the number required and the manner in which they are based, will ultimately be determined by the rules of any game in which these miniatures are used.

The hobby can be very fickle and is often subject to frequent change and new trends. This might be caused by the publication of new rules, but it can also be brought about by a manufacturer’s desire to fuel continued sales. Such changes, when they occur, can be quite extreme, even to the extent of rendering obsolete most elements within a preceding range. Whilst some modellers welcome these updates, as in their eyes it keeps both the game and their collection fresh, other gamers find the continuing need to replace old miniatures with newer versions very frustrating. Resistance to what some regard as a cynical attempt to maintain sales and profits, coupled with a desire by others to return to the games of their youth, has given rise to a number of retro gaming movements. Two such examples are Oldhammer and Middlehammer, where gamers are using early editions of the Warhammer rules while collecting vintage models from the same era, together with new miniatures that have been sculpted in an ‘old school’ style.

In order to increase the longevity of their models gamers may wish to incorporate a degree of flexibility, enabling their use in more than one type of game. Such future proofing may require careful consideration of basing solutions for example, so as not to exclude huge numbers of miniatures by limiting their comparability across different games. Therefore an understanding of the different styles of game in which these models are likely to be used is helpful, if not necessary.

Role-Playing Games

RPGs (role-playing games) usually involve a small group of players embarking on an adventure in which they will journey from one encounter to another as they progress through various scenarios in the game. Players normally control one or two models, each of which are known as player characters. A further individual, acting as a referee, controls all the other personalities, creatures and monsters in the game; these are known as non-player characters. Each encounter, the outcome of which is usually determined by rolling a number of dice, requires a small selection of individually based miniatures. These models need to be distinct from one another so that any injuries or wounds sustained during the game can be attributed to the correct non-player character, ensuring that the appropriate model is removed from play once death occurs.

A small dungeon adventure game using only a few models to represent a variety of player and non-player characters.

To this end it is wise not to use multiple versions of the same model. This will help to reduce the chance of any confusion arising on the gaming table, particularly if the encounter involves contact with large numbers of non-player characters, such as a goblin raiding party. Since all models have the potential to fight with individual characteristics and inflict different degrees of damage on players, it is not appropriate simply to remove random miniatures from the back of the war party. In addition, players may choose to target one particular model for strategic reasons, so keeping track of precisely what is going on is vital to the game.

It may also be necessary to collect different versions (but not duplicates) of the same figure, for example a fighter in chainmail armour with a sword, and the same fighter also wearing a cloak and carrying a larger sword and shield. These models can then be used to represent the development of a player character throughout the game as they acquire more accoutrements, collect artefacts, obtain different weapons or develop their skills and proficiency to a higher level.

Where mounted figures appear in the game, it can be useful to have an additional dismounted version of the rider and a riderless version of the steed to account for the occasions when either the horse is not being ridden, or when one or the other has been killed and the model removed from play.

To a certain extent, the size and shape of each RPG miniature’s base is of little importance or significance, being instead a question of visual aesthetics. In the hobby’s infancy a miniature and its base were usually cast as one piece, and bases were typically of an irregular shape determined by the miniature’s pose. Then in a desire to obtain uniformity throughout their collection, many modellers mounted their RPG miniatures on washers, coins or plastic bases, matching the diameter of the base to the size of the model, using 20mm washers for small creatures such as halflings and goblins, and 25mm for the likes of humans or orcs.

The development of separate plastic bases in the mid-1980s resulted in a standardization of sizes and shapes. Although RPG figures were originally sold with the same square bases that accompanied wargaming miniatures, the majority are now supplied with either hexagonal or round bases.

Skirmish Games

Skirmish games are small-scale combat games that usually involve players controlling groups of between twelve and twenty miniatures, known as a warband. These small groups of figures fight one another on a gaming table of modest proportions, which normally need not be any larger than 4 × 4ft (1.2 × 1.2m2).

Each warband is comprised of a variety of models, which may include different troop types along with a hero and perhaps an additional character with magic powers. Since these models typically fight as individuals, the direction from which an attack is received is of less significance than in a mass battle wargame. Regimented units can gain bonuses for attacking an enemy in the flank or rear, but a gang of warriors fighting in loose formation has no flank or rear. It is assumed that each individual member of a warband will be able to turn on the spot in order to face an enemy. As a result, most skirmish games incorporate models mounted singly on round bases.

Skirmish games are small-scale combat games. Some rules come with everything you need to start gaming, like this ‘Battle for Troll Bridge’ box set from Warploque Miniatures.

Given the small number of models that make up a warband, many rules allow individual troops to sustain more than one wound. Wounds are therefore attributed to particular members (or models) within the warband and are tracked in much the same way as in role-playing games. Again, for this reason it is preferable to avoid acquiring duplicate examples of the same miniature.

In circumstances where duplicates do exist, the problem can usually be overcome by painting the models with slightly different colour schemes, or by minor conversions. This may include changing the weapon that one of the duplicate miniatures is carrying, or swapping a head. It is worth checking the rules before undertaking a weapon swap, however, as some rules specify that the weapon carried by a miniature must represent the actual weapon being employed in the game in order to avoid any confusion.

Mass Battle Wargames

Mass battle games typically require the acquisition of large numbers of miniatures, all of which need painting. It is worth remembering that the smaller these troops are in stature, then the greater they will be in number. Someone wishing to create a goblin army will inevitably end up painting hundreds of figures, whereas someone fielding an army of ogres may only have a dozen models to paint. On balance the time taken to complete either of these armies is probably the same, since ogre models, being larger, contain more detail; however, the prospect of having to paint several hundred small models can still be quite daunting so it is important to choose an army that will be just as enjoyable to paint as it is to game with.

Whereas RPG or skirmish games employ individual models that move, fight and receive wounds independently of one another, individual miniatures in a rank-and-file unit are part of a larger group, moving together and fighting the same opponents together. Any wounds inflicted on the unit traditionally involve models being removed from the rear ranks, one for each wound received. To this end, collecting duplicate miniatures ceases to be an issue, indeed it can be a distinct advantage. Not only can the repetition of similar or identical features on multiple figures speed up the painting process, but it can also provide the unit with an overall cohesive appearance that conveys a sense of uniformity across regiments of the same troop type.

Some rules do not require any miniatures to be removed from the gaming table until the unit in question is utterly destroyed. This has given rise to rules that allow units to be fielded as one-piece dioramas – Mantic’s ‘Kings of War’ is one such example. This can result in the unsettling spectacle of seeing a great swathe of figures together with any accompanying scenery, such as trees or even buildings, being marched across the battlefield – in the case of an undead skeleton unit, this could mean it is not only the skeletons that are moved around the battlefield, but also the entire graveyard from which they have arisen.

The prospect of painting several hundred miniatures can be quite demoralizing, so choose an army that will be just as enjoyable to paint as it will be to game with.

Although miniatures fixed within a diorama have the potential to look extremely impressive, this approach does have its drawbacks. Not only does it require the use of wound markers or a score card for recording unit casualties, but not being able to remove those casualties can produce a unit or indeed an entire army that appears undiminished for the duration of the battle, regardless of the damage inflicted upon it. Permanently fixing miniatures to a diorama also prevents their use elsewhere. The desire to do so will mean purchasing a duplicate set of figures, which then have to be assembled and painted all over again.

For this reason some gamers are turning to MDF and plywood movement trays, which are available in an ever-increasing number of different designs. The cavities provided to accommodate various bases allow miniatures to be slotted into place, swapped around, or removed as and when required without detriment to the visual impact of the diorama.

Whilst collecting and painting large armies in the popular gaming scales (such as 25mm or 28mm) can be very expensive and time-consuming, the rewards can also be significant, not only in terms of the hours of enjoyment the modeller gains from creating their army and then deploying it in battle, but also in terms of the sheer visual spectacle that is generated when multiple ranks of beautifully painted miniatures are lined up across the gaming table.

For those gamers wishing to create huge armies and indulge in truly epic battles, there exists the option of choosing miniatures in a much smaller scale. Instead of engaging in a battle where the size of each model means that opposing forces rarely number more than half-a-dozen units, and fighting takes place at company or regimental level, waging war at smaller scales can allow battles to be conducted at brigade or even divisional levels. However, the delicate nature of these smaller miniatures often requires whole units to be assembled on one base, the result of which, when taking casualties, is an army that is eroded unit by unit, rather than figure by individual figure. Unless you are commanding a significantly large force, this can create the impression that an army is melting away rather rapidly in front of your eyes.

WHAT IS FANTASY?

The fantasy modelling genre is very broad, and today we find a wealth of miniature manufacturers producing a huge range of fantasy figures that cater for almost every taste and every interest imaginable. This is without mention of the huge back catalogue of discontinued miniatures that are still available to the collector, in particular via the internet, through the sale of pre-owned and second-hand models dating from as far back as the early 1970s.

Furthermore the fantasy modeller has the added advantage of being able to make use of many historical miniatures, particularly when creating a human army to fight in a fantasy setting. The fact that their army inhabits a fantasy world frees the modeller from the many constraints that would otherwise be imposed were they to conform to the requirements of historical accuracy. Fielding a fantasy army provides the added enjoyment of being able to deploy and assail the enemy with a variety of exotic troop types not found in historical warfare, such as demons, dragons, giants and countless other mythical creatures.

Indeed the word ‘fantasy’ itself is not without ambiguity, and is open to very broad interpretation. It can mean very different things to many different people, and although a detailed analysis of its cultural meaning lies beyond the scope of this book, the widely accepted definition is that of a fictitious world in which magic and supernatural powers have a primary role.

Having said that, it is the author’s opinion that the subject does warrant further exploration, particularly since such a broad definition allows the modeller considerable scope in their interpretation of the subject matter. In its application within the context of miniature modelling a number of important distinctions can be made.

Traditional Fantasy

Traditional, or High Fantasy as it is sometimes called, refers to a world of wizards, chivalrous knights, dragons, dark lords and monsters. It is a world best exemplified by the novels of J. R. R. Tolkien, The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings, which arguably, even to this day, remain two of the most influential works within the fantasy genre. These novels in turn have given rise to a number of games that seek to recreate aspects of Tolkien’s world on the gaming table. These include ‘Dungeons & Dragons’ (D&D) and ‘Advanced Dungeons & Dragons’ (AD&D) by E. Gary Gygax and Warhammer, the fantasy miniatures mass-battle game developed by Games Workshop.

This 6mm goblin army from Baccus not only looks very impressive as it takes up a defensive position on the gaming table, but it also contains exotic creatures within its ranks in the form of a mighty dragon and Orc Boss on Wyvern from Perfect Six.

For many purists this is where the definition of ‘fantasy modelling’ both starts and ends, while others, the author included, adopt a wider interpretation. For some people traditional fantasy also encompasses more recent works, such as the Discworld novels by Terry Pratchett, or the Game of Thrones saga by George R. R. Martin, as they, too, are stories laced with sorcery, strange mythical beasts, or the inevitable life and death struggle between forces of good and evil.

Classical Fantasy

Classical fantasy draws its inspiration from the stories and mythology of ancient and medieval times, whether that is from the Viking sagas or the legends of Ancient Greece and Rome. It includes stories such as Beowulf and Jason and the Argonauts, in which mere mortals pit their wits against their many gods and the fiendish creatures that these gods unleash. The latter of these examples was made into a film in 1963, where the stop motion animation and model-making skills of the late Ray Harryhausen proved hugely influential for the author and many other modellers of that generation.

The important distinction to make between traditional and classical fantasy is that in traditional fantasy imaginary creatures and races inhabit an altogether imaginary world, whilst in classical fantasy imaginary beasts and monsters inhabit a world that is, in all other respects, historically accurate.

Folklore and Fairytales

With their stories of faraway lands populated by giants, trolls, witches, gallant princes and damsels in distress, fairytales have for a long time provided miniature modellers, sculptors and manufacturers with a huge source of inspirational material, although whether or not they would openly admit to this is another matter. Fairytales have been made more palatable for the adult modeller in recent years following the release of films such as Jack the Giant Slayer, Maleficent and Snow White and the Huntsman, all of which have added a darker edge to the original tales whilst providing a mouth-watering array of computer-generated monsters and special effects to feed the modeller’s imagination.

Victorian Fantasy

Whilst steampunk is often considered to be a sub-genre of science fiction in which advanced technology is substituted by steam-powered machinery, it is ironically not a futuristic genre at all. Typically spanning a period in history that starts with the emergence of black powder weapons in Western Europe and ends in the early part of the twentieth century with the outbreak of World War I, much of the genre’s imagery is Victorian. Attempts to incorporate elements of steampunk within traditional fantasy games have led to some scathing criticism, with the results being referred to as clockwork fantasy.

Clockwork pistols and steam-powered, hydraulic exo-armour aside, it is often forgotten that many of the creatures that now inhabit traditional fantasy worlds were made popular by writers from the Victorian era. This includes monsters from many classic horror stories, such as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein or Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. One of the more notable of these is Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which inspired the ‘classic horror’-flavoured Warhammer Vampire Counts army.

To dismiss the Victorian era outright as not being relevant to fantasy is also to dismiss such marvellous and inspirational works as Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth or Edgar Rice Burroughs’ The Land that Time Forgot. These have undoubtedly influenced the development of many beautiful models from companies such as Foundry and Antediluvian Miniatures, giving the fantasy figure modeller ample justification for combining Victorian characters with dinosaurs and prehistoric tribesmen, were any such justification needed.

Contemporary Fantasy

Contemporary fantasy is the last notable reinterpretation of the genre, about which any discussion would not be complete without reference to the Harry Potter books by J. K. Rowling. These tales, of a young orphan and his friends who, after enrolling in a modern-day school for wizards, go on to fulfil a prophecy by defeating the forces of darkness, were preceded by literary classics such as Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland and C. S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia, all of which again provide further inspiration and freedom of interpretation for the fantasy figure modeller.

SIZE MATTERS

Fantasy figures quite literally come in all shapes and sizes. Today, by far the most popular are those miniatures that are described as being ‘28mm’, but these are not the only fantasy figures on the market.

Unlike traditional toy soldiers, where scale is expressed as a ratio, such as 1:72nd or 1:35, or the model railway industry, which refers to scale using letters or numbers such as ‘OO/HO’ or ‘Gauge 1’, the scale of a wargaming figure is given in millimetres, such as 28mm or 54mm. This measurement is determined by the height at which a 6ft (1.8m) tall human is reproduced in miniature. In a world populated by orcs, ogres, dwarves, giants and halflings, this is an important distinction to make.

The size of these models will naturally vary in relation to the size of a human, so a 28mm giant standing 18ft (5.5m) tall would be represented in miniature by a model measuring approximately 84mm in height, while a 28mm model of a halfling would be approximately 18mm tall, as halflings rarely exceed 4ft (1.2m) in stature. The use of the word ‘approximately’ is deliberate, as the interpretation of scale is not an exact science, and size variation does exist among miniatures purported to be of the same scale.

Scales for the Gamer

Those who collect miniatures for use in a particular game will likely find that any question of scale has already been determined by the rules. The majority of these are intended for use with 28mm miniatures, which has undoubtedly helped 28mm become by far the most popular scale. The scale of the miniatures is sufficient to accommodate enough detail to make modelling a worthwhile and rewarding endeavour, whilst providing a satisfactory gaming experience within a manageable area, such as on a dining-room table or a 6 × 4ft (1.8 × 1.2m) gaming board. Either of these surfaces offers sufficient room for reasonable variation in terrain if wargaming, or to build up a decent sized floor plan when role playing inside dungeons or caverns.

By choosing a popular scale the modeller opens up the possibility of utilizing a wide variety of miniatures from different manufacturers. Despite this, many fantasy gamers with human armies seem surprisingly happy to overlook the plethora of well-established historical ranges, all of which have the potential to work as a much more affordable alternative. Other fantasy modellers who dislike the oversized and caricatured appearance of some orc miniatures have been known to use human barbarian, Hun or Mongol models instead, achieving an orc-like appearance through minor conversions and by modifying the way these models are painted.

This 28mm halfling stands 18mm tall, giving a scale height of about 4ft. The giant model creeping up from behind is 240mm tall, which is the scale equivalent of a towering 52ft.

Changes in attitude towards the appearance of creatures such as orcs may have been brought about by recent developments in the way they have been depicted, particularly in films such as the Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit. Here they appear far more human-like than in many of the traditional fantasy games such as AD&D or Warhammer. Indeed, if the aim is to create an orc army in 6mm, then wellarmoured Lord of the Rings-style orcs would be almost indistinguishable from any other heavily armoured human at that scale, and it is the style in which the models are painted that will clearly define them as orcs.

When creating large armies comprised of hundreds of miniatures, then clearly working at a smaller scale has its advantages. To some extent Games Workshop acknowledged this fact when they released a 10mm version of their Warhammer fantasy game, called Warmaster. Indeed the author vividly recalls seeing two huge Warmaster armies lined up and ready to do battle at a wargaming show in the late 2000s, and it was a truly impressive sight. Recreating these forces in 28mm, where the detail inherent in each miniature compels the modeller to paint every feature right down to the whites of the eyes, would have taken a lifetime, whereas modelling these huge armies in 10mm made the task a practicable reality. It is a great shame that at the time of writing this book Warmaster has been discontinued, although both Pendraken and Kalistra produce their own very extensive and beautiful fantasy ranges at similar scales.

If the aim is to cover the wargaming table with a patchwork quilt of regiments and units, then it might be worth considering going smaller still. To this end a number of fantasy armies are available in 6mm, which when seen ‘en masse’ can produce an overall result that is visually very spectacular, even at such a small scale.

Some rules allow the gamer to decide for themselves which scale they wish to use and, in these situations, 15mm is a popular alternative to 28mm. Whilst still manageable as a scale for role playing (as demonstrated by the Traveller Sci-Fi RPG of the early 1980s), it is more frequently used by wargamers who are looking to fight larger battles than might be possible using 28mm models. If the aim is to model large fantasy armies with models that still convey a significant amount of detail, then the scale of compromise is most definitely 15mm. Whilst the modeller is spared the task of having to quite literally paint the whites of the eyes on every miniature, they still hold a satisfactory amount of detail with regard to the armour, type of weaponry and any other assorted accoutrements that a warrior might carry into battle.

Some skirmish games offer the opportunity to use larger models, such as 54mm or even 75mm, particularly in games where each player controls fewer than half-a-dozen miniatures. With fewer models represented at much larger scales, the gaming table typically encompasses a smaller area in which combat can take place, such as the courtyard of a ruined castle or a quayside in a medieval town. In addition, many of these games allow fighting at different levels, so whilst a 4 × 4ft (1.2 × 1.2m) gaming table may not seem very large, combat develops an extra dimension when models are able to climb onto buildings and fight from rooftops or battlements.

Scales for the Collector

The miniature collector is not encumbered by the limitations of rules or any restrictions concerning the practicalities of game play or miniature scales. To this end they are able to purchase miniatures in any scale and from any manufacturer with little concern, other than the inherent challenge of completing the model. A number of manufacturers produce miniatures with the collector in mind, in scales ranging from 54mm through to 120mm or even 240mm. Many companies also produce busts at larger scales still, providing the modeller with an opportunity to undertake very detailed work indeed.

Scale really only becomes an issue for the collector if they are wanting to convert models and are looking for alternative ranges from which to source suitable component parts.

Tools, Equipment and Modelling Materials

2

IT IS NOT NECESSARY to purchase a long list of tools before starting a new modelling project. Indeed, painting can begin with as little equipment as a couple of brushes, a handful of paints, a craft knife and some glue, together with a few additional household items such as kitchen roll, an old plate and a mug of water. Many of the tools and materials detailed here can be collected over time, as and when projects require them. This chapter is intended as an overview of the range of tools and materials that might prove useful at some stage in the hobby, as your modelling skills develop and projects become increasingly more sophisticated.

Those who are new to the hobby may prefer to start with just a handful of miniatures and an introductory painting set, or to purchase only the essential paints. With a primary pallet of red, blue and yellow, together with black, white, silver and gold, it is possible to mix all the colours that might be required for a simple painting project. The internet is a great resource for those seeking further information on mixing colours, and researching colour theory and the artists’ colour wheel is highly recommended.

From a primary pallet of red, blue and yellow, together with black, white, silver and gold, it is possible to mix and blend all the colours that might be needed in a small painting project.