20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

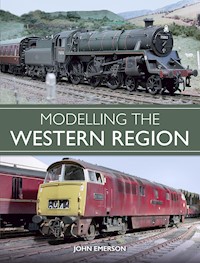

The Western Region of British Railways has always held a special appeal for railway modellers. Formed in 1948, the Western Region carried on the traditions of The Great Western Railway more or less unchallenged until the regions were abolished in the 1990s. Modelling the Western Region provides all the advice you need to model your own railway layout based on this fascinating region and era. This book considers the historical background of the Western Region; it reviews available ready-to-run and kit-built steam and diesel motive power; explains Western Region signalling practice; discusses rolling stock typically used on the Western Region and, finally, provides practical suggestions for branch and main line layouts. An essential reference book, fully illustrated with 203 colour, 46 black and white photographs and 19 illustrations, for all modellers of all abilities and in any scale, who wish to model the Western Region.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

MODELLING THE

WESTERN REGION

JOHN EMERSON

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2019 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2019

© John Emerson 2019

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 528 2

Acknowledgements

My sincere thanks for help and assistance with photographs to Simon Kohler and Hornby Hobbies, Dennis Lovett of Bachmann Europe plc, Paul Chancellor at ColourRail, Frank Dumbleton of Didcot Railway Centre, Paul Bason, and of course my colleague during our time with BRM, Tony Wright. Thanks are also due to Mick Nicholson for his invaluable help over the years with my various queries about signalling matters.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

1THE WESTERN REGION – AN INTRODUCTION

2NATIONALIZATION TO PRIVATIZATION

3MOTIVE POWER – THE AGE OF STEAM

4‘FLYING BANANA’ TO ‘TURBO STAR’ – DAWN OF THE DIESELS

5MOTIVE POWER – DIESEL DEVELOPMENTS

6PASSENGERS AND PARCELS

7DELIVERING THE GOODS

8LOWER QUADRANT TO MAS: WHY SIGNALS?

9SETTING THE SCENE – BUILDINGS AND STRUCTURES

10PLANNING A LAYOUT

11TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY SURVIVORS

APPENDIX: ABSORBED LOCOMOTIVES

USEFUL WEBSITES

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

INDEX

PREFACE

In the course of a year we see a large number of model railway layouts at exhibitions, private displays, clubrooms and houses and, although we have no figures to hand, it seems to us that more modellers base their layouts on Great Western or Western Region practice than on that of any other company. Not my own words, but those of G. M. Kichenside, editor of the much missed Model Railway Constructor back in April 1963. Since those words were written, of course, the Western Region has long vanished, along with the steam engines that had reigned supreme upon it for so long, the diesel hydraulics that enjoyed a much briefer life and the ‘factory’ that built them – and almost everything else for the Western Region – Swindon, ‘home of the Gods’!

Some half a century later, the railway modeller’s enduring enthusiasm for the Great Western Railway (GWR) and its successor the Western Region (WR) shows little sign of abating. The picturesque GW branches that lasted until given their death sentence in the Beeching Report – coincidentally also published in 1963 – still remain popular subjects for smaller layouts. My own latest modelling project is based on Brimscombe, situated on the climb up to Sapperton Tunnel through the ‘Golden Valley’, and over which the famous ‘Cheltenham Spa Express’ ran. Manufacturers continue to produce ever more realistic models of the products of Swindon in all scales, as well as the various British Rail (BR) standard locomotive types, diesel electrics and diesel multiple units (DMUs) that were such a familiar everyday sight over all parts of the WR until its ultimate demise in 1992.

Although it’s impossible in a mere two hundred or so pages to cover every facet of modelling the Western Region, its rolling stock, infrastructure and operations, my hope is that this book will go some way to inspiring and informing everyone who seeks to model the Glorious Western Region.

John Emerson

Heckington

April 2018

CHAPTER ONE

THE WESTERN REGION –AN INTRODUCTION

Depending upon your point of view, the former Great Western Railway was either ‘God’s Wonderful Railway’ or the ‘Great Way Round’. Brought up in 1950s Cheltenham, where the famous ‘Cheltenham Flyer’ began its high-speed journey to Paddington – going in the opposite direction at a crawl behind a tank engine – I still incline to the former. Amongst all of the ‘Big Four’ companies formed as a result of the 1921 Railways Act, the GWR was the only one that did not have to deal with the problem of uniting a group of similar-sized railway companies into one larger whole – the Great Western did not even have to change its name. Amongst the ‘Big Four’ railway companies brought about by the Grouping, the GWR alone could boast an unbroken history stretching from its conception in 1833, through amalgamation and absorption of other lines in 1922, and up to its demise upon nationalization in 1948.

Throughout the post-war austerity years of the 1950s, and well into the early 1970s, some of the most popular layouts at shows and in the model press were branch lines of GW or WR origin – so much so that, indirectly, this led a group of disgruntled modellers forming the LMS Society in protest. The WR was arguably fortunate in that, unlike some of the more austere lines of other regions, it had inherited many branch lines that went to popular and well-publicized seaside holiday destinations – such as Newquay, Brixham and Kingsbridge – all with backdrops of attractive scenery. Some, such as Minehead and Kingswear, were engineered to main-line standards and capable of taking some of the heaviest locomotives. Many of these stations were relatively small, or their track plan could be reduced to fit the restricted space available to modellers. With a fair amount of published information from the likes of Michael Longridge in the Model Railway Constructor, the layout plans of Cyril Freezer in the Railway Modeller and a limited amount of readily available locomotives and rolling stock from the trade in the decades of austerity following the war years, it made sense to model a small scheme where something like an ‘auto-tank’ and trailer were the mainstay of services.

Regal splendour – shafts of sunlight highlight doyen of the ‘King’ class No. 6000 King George V arriving with the up ‘Cambrian Coast Express’ at Birmingham Snow Hill.G. PARRY COLLECTION/COLOURRAIL

However, the newly created WR was not just about picturesque branch lines. The main routes from London ran from Paddington to Bristol Temple Meads over the easily graded route known as ‘Brunel’s Billiard Table’, over the steep Devon banks to Plymouth and Penzance in the south-west with its heavy summer holiday traffic, Neyland and Fishguard on the Welsh coast with ferry connections to Ireland, through Banbury, Birmingham (Snow Hill), Wolverhampton (Low Level) and Shrewsbury to North Wales, as well as routes to Weymouth, Salisbury and Basingstoke. Western Region locomotives could even be regularly seen at Crewe in the heart of London Midland Region territory.

A procession of famous-named trains left Paddington each day heading for various destinations. The ‘Torbay Express’, ‘Mayflower’, ‘Royal Duchy’ and ‘Cornish Riviera’ headed for south-west holiday haunts, ‘The Inter-City’ and ‘Cathedrals Express’ served Birmingham and the Midlands, the ‘Red Dragon’ and ‘Capitals United’ ran to Cardiff and Swansea, while ‘The Cambrian Coast Express’ journeyed via Wolverhampton (LL) and Shrewsbury to Aberystwyth and Pwllheli. Other named trains running over the Western Region included the ‘Cheltenham Spa Express’, ‘Merchant Venturer’ and ‘The Cornishman’, all running from the mid-1950s in the revived but not really Great Western ‘chocolate and cream’ livery.

The GWR just prior to nationalization – ‘Star’ class 4-6-0 No. 4013 Knight of St. Patrick leaves Malvern Road, Cheltenham, with a Wolverhampton– Penzance train on 22 April 1946.JOHN EMERSON COLLECTION

In the immediate post-war years, the GWR was the subject of a great many layouts. The O gauge layout of W. S. Norris was a notable example – finescale at a time when coarse scale was the norm – although still using outside third rail current collection. The popularity of GW/WR layouts has not diminished over the years.

Modellers today are fortunate in having a wealth of ready-to-run locomotives and rolling stock available to run ‘out of the box’, as well as a vast library of published colour albums and DVDs to aid research. To model the WR successfully it is certainly not necessary to be steeped in GWR history, although modellers should be aware that WR practice differed significantly in a number of ways to other parts of the BR system, thanks to the influence of more than a century of continuity and tradition.

FAMOUS NAMES

From the earliest days, several influential personalities emerged who stamped their individuality on the GWR and whose names have echoed down the years, the most famous being Isambard Kingdom Brunel who surveyed the original route from London to Bristol when aged just 27 and proposed using his 7ft broad gauge (later increased to 7ft ¼in). His Paddington terminus is still in use today, as are many of his other great works, including the Royal Albert Bridge spanning the Tamar at Saltash, Box Tunnel, Wharncliffe Viaduct (first viaduct to carry electric telegraph) and the world’s flattest arch bridge over the Thames at Maidenhead on the Great Western Main Line (GWML). From 1877 to 1902, William Dean was Chief Locomotive Superintendent, several of his ‘Dean Goods’ 0-6-0 and ‘Duke’ 4-4-0s surviving into the very early years of the BR (WR) period.

George Jackson Churchward (Locomotive Superintendent from 1902 to 1922) began a steady but continuous programme of development and standardization of motive power at Swindon, including the first 2-8-0 in the UK (1903), forerunner of the 28xx 2-8-0 class, and the Great Bear – the first ‘Pacific’ locomotive in the UK (1908). His development of the four-cylinder 4-6-0 culminated in the ‘Star’ class (1906), several surviving into early BR days. Other notable locomotive classes introduced under Churchward, which lasted well into the BR period, include 42xx 2-8-0T, 43xx ‘Mogul’ 2-6-0, 44/45xx ‘Small Prairie’ 2-6-2T and 47xx 2-8-0. Charles Collett succeeded Churchward in 1922, developing the ‘Stars’ into the highly successful ‘Castle’ class (1923), and introducing various classes of ‘Pannier’ and side tanks, as well as the 48xx (later 14xx) ‘auto-tanks’. Other types included the famous ‘King’ class 4-6-0s (1927), ‘Collett Goods’ 0-6-0 (1930) and two-cylinder ‘Hall’ and ‘Grange’ 4-6-0s. The first diesel railcars were also introduced under Collett, and many of his designs saw out the last days of steam on the WR.

Not much had really changed after a decade of nationalization. Standard GWR loco types were still in front-line service, although rolling stock was almost exclusively BR Mk.1s. No. 4073 Pembroke Castle leaves Swindon with an up train.JOHN EMERSON COLLECTION

Reduction of WR route mileage continued into the post-Beeching era. A 3-car class 120 DMU leaves Cheltenham Racecourse with the last passenger service over the Cheltenham– Stratford-upon-Avon line, organized by the Railway Invigoration Society. The line finally closed in 1976.

The last Chief Mechanical Engineer (CME) of the GWR was Frederick Hawksworth (1941–49). His tenure saw the introduction of the two-cylinder ‘County’ (1945) and ‘Modified Hall’ 4-6-0s (1944–50). Hawksworth’s 15xx/16xx and 94xx pannier tanks, although designed for the GWR, were built after nationalization, as were diesel shunters Nos 1501–1507, and the two gas turbine locomotives Nos 18000 and 18100. Following nationalization, Robert Riddles, Roland C. Bond and E. S. Cox, all former LMS men, oversaw the design and introduction of the ‘BR Standard’ classes of steam locomotive for the Railway Executive of the newly nationalized British Railways. The 75xxx 4MT 4-6-0s, 77xxx 3MT 2-6-0s and 82xxx 3MT 2-6-2Ts were all built at Swindon, as were fifty-three of the 9F 2-10-0s, including Evening Star, the last steam locomotive to be built for British Railways – construction apparently being delayed to ensure it was Swindon that built the last one! Riddles retired on the abolition of the Railway Executive in 1953, and Roland Bond became CME, BR, Central Staff. Later, in 1965, he became General Manager, BR Workshops, retiring in 1970.

BROAD-GAUGE LEGACY

Unlike the majority of the rest of British Railways, the GWR routes from Paddington to Penzance, Weymouth, Wolverhampton and Neyland, as well as many branches off them, were built to Brunel’s broad gauge. Although conversion to standard gauge had been completed way back in 1892, it left a legacy of wider track formations, particularly noticeable at stations where the distance between running lines was noticeably wider than the usual ‘six foot’ of standard gauge lines. Obviously, this did not apply to ex-GWR lines built after the abolition of the broad gauge.

The loading gauge for ex-broad gauge main lines was the largest of all pre-nationalization railways, allowing a maximum height of 13ft 5in (3.58m) and overall width of 9ft 8in (2.95m). The 60xx ‘King’ class locomotives were designed to take full advantage of these generous dimensions, although their weight and size restricted their operational use to ‘Double Red’ routes on the WR, and in preservation, overall height has had to be reduced before being allowed to operate on the current rail network. Some ex-GWR passenger coaches, such as the ‘Centenary’ stock and ‘Super Saloons’ were also built to the maximum load gauge. Being 9ft 9in overall width (classified ‘Red Triangle’) they too were restricted in the number of WR routes they could operate over and on the rest of the national network.

Legacy of Brunel’s broad gauge – the wider than ‘six foot’ spacing between the Up and Down lines are apparent at Moreton-in-Marsh in the early 1970s. Class 165/166 ‘Turbostars’ built for ex-GWR routes are 9ft 3in (2.81m) wide, but class 170s derived from them are 8ft 10in (2.69m) wide.JOHN EMERSON COLLECTION

Many of Brunel’s original station buildings survived on ex-broad gauge routes well into the 1960s before being demolished – some may say officially sanctioned vandalism – although Culham and Mortimer are two Brunellian station buildings that still survive in use today. It is interesting to note that parts of the original London–Bristol route were nominated for World Heritage Site status in 1999.

NATIONALIZATION TO PRIVATIZATION

After nationalization, former GWR locomotives were the only ones to retain their original numbers, due to the practice of using cast cabside numberplates. Apart from locos that went for early withdrawal, they all gained cast smokebox number plates in line with other BR loco types. It was a Western Region locomotive that first appeared with any sign of the newly nationalized rail network when 4946 Moseley Hall was outshopped in January 1948 in full GWR lined green livery with ‘British Railways’ in GWR-style lettering on the tender; No. 4085 Berkeley Castle being similarly treated in August 1948. The period from 1948 to 1950 saw many experimental liveries trialled for passenger locomotives and rolling stock, before any conclusions were reached. Consequently, it was several years before the old GWR and other company liveries disappeared completely and the new BR livery scheme was fully implemented. A variety of lined blue or green schemes were applied to a number of ‘Castles’ and at least four ‘Kings’, first with ‘British Railways’ in full on tender and tank sides.

From 1949/50 liveries began to settle down into lined green for passenger locos (‘Castle’ and ‘King’), lined black for mixed traffic (‘Saint’, ‘Hall’, ‘Grange’, Manor’, ‘County’ and 43xx) and unlined black for goods’ locos with the BR ‘lion and wheel’ totem. During the 1950s, many older GW loco types became extinct, most without receiving new liveries, smokebox number plates or even a decent repaint. However, ‘Castles’, Manors’, ‘Modified Halls’ and pannier tanks were still being built at Swindon, alongside the new ‘BR Standard’ classes.

British Railways livery for passenger stock from 1953 was crimson and cream for corridor stock (known as ‘blood and custard’ to enthusiasts) and crimson for non-corridor and parcels’ stock. This was superceded in 1957 by lined maroon. In 1956, the WR was allowed to introduce a version of the old GWR ‘chocolate and cream’ livery for named trains. Unsurprisingly, WR management took full advantage of this by introducing a number of new named trains and the livery became more widespread – the new WR livery also appeared in many unnamed trains due to availability, remarshalling of stock and so on.

This photograph has appeared several times in print, but it shows ‘Castle’ class 4-6-0 No. 4091 Dudley Castle in experimental Apple Green livery at Chippenham in 1949.K. LEECH/COLOURRAIL

Today it is difficult to appreciate the sheer numbers of locomotives and rolling stock on the pre-Beeching railway, as well as the vast yards and depots with sidings full of wagons, vans and coaches. Inefficient and loss making it may have been, but what a glorious and inspiring sight awaited modellers at locations like Worcester in the late 1950s and early 1960s.JOHN EMERSON COLLECTION

In 1955, No. 6997 Bryn-Ivor Hall appeared in lined green, beginning a general move away from lined black for mixed traffic locos, including the ‘Prairie’ tanks. Some of the 43xx ‘Moguls’ appear to have been outshopped in plain unlined green, whilst others received full lining. From 1956/57 a new BR crest appeared, universally referred to as the ‘cycling lion’. Initially, this appeared on tenders and tanks with the lion facing forward on both sides. However, as this was an ‘heraldic achievement’ – officially granted by the College of Arms – objections to the right-hand (dexter) facing lion were raised on the grounds that the design originally submitted had the lion facing to the left (sinister). Most right-facing lions were subsequently removed and replaced by the correct left-facing transfer.

The new crest was applied to steam and diesel locomotives and a ‘roundel’ featuring the lion and wheel was applied to some coaching stock and newly introduced DMUs and railcars. From 1965, the BR ‘arrow of indecision’ was introduced for all locomotives and rolling stock repainted into the new BR corporate colours. Locomotives (apart from steam engines) were repainted rail blue with all-over yellow ends, whilst passenger corridor stock received lined blue/grey, and non-corridor and parcels’ stock was plain blue. Although the ‘arrow of indecision’ was heavily criticized when introduced over half a century ago, both it – and the BR Corporate Design Manual – are now recognized as outstanding pieces of industrial design, the BR symbol outlasting British Rail to become a universal symbol for railway stations – not train stations – on the privatized network.

From 1958, diesel hydraulics began to appear, gradually displacing steam on the prestige services, leading to the elimination of steam traction in 1965, although inter-regional workings still brought steam locomotives on to the WR until the final end of steam on the national network in 1968. The hydraulics themselves gave way to diesel electric traction and the new High Speed Train services during the 1970s, transforming journey times.

The ‘Beeching Report’ in 1963 signalled the end for many of the traditional but unremunerative branch and secondary lines, and some routes were singled in a round of cost-cutting exercises. A series of regional boundary changes saw parts of the WR absorbed into the London Midland Region (LMR), while parts of other regions were transferred to the WR, including the ex-Somerset & Dorset Joint line north of Templecombe, which eventually closed in 1966. The run down of the hydraulic fleet and privatization of BR’s engineering works ultimately led to the closure of the Swindon works itself in 1986.

Although large numbers of steam locomotives escaped the cutter’s torch at Woodham’s scrap yard in Barry, those sent for cutting up at other sites, such as Cashmore’s in Newport, were not so fortunate.JOHN EMERSON COLLECTION

The WR in the post-steam age – D1050 western ruler waits for the road at Exeter St Davids.JOHN EMERSON COLLECTION

Keeping ahead of the game – new from Hornby for OO gauge modellers is the very latest Hitachi class 800 ‘Intercity Express’ unit in GWR livery. The full size units entered service in 2018, displacing the 40-year-old HSTs.HORNBY HOBBIES

As a prelude to privatization, British Rail was split into business sectors, and the Railways Act (1993) signalled the end of the WR as an autonomous region, paving the way for the break up of the system into a series of franchises for the newly created Train Operating Companies (TOCs). Today, Network Rail are undertaking a massive, if somewhat troubled, scheme to electrify the GWML, which, when eventually completed, will further transform services for passengers. And, in 2015, Train Operating Company First Great Western rebranded their services as Great Western Railway, operating over much of the old GWR network – it seems that the spirit of the ‘old company’ still refuses to die!

WESTERN REGION TIMELINE

1948Nationalization (Transport Act 1947)1949First gas turbine locomotive (ordered under GWR)1955BTC publish Modernisation and Re-Equipment of British Railways (the ‘Modernisation Plan’)1956WR ‘chocolate and cream’ livery introduced for new named trains1958D600 A1A-A1A ‘Warship’ diesel hydraulics introduced D800 B-B ‘Warship’ diesel hydraulics introduced (D800–32/66–70 – later Class 42) Somerset & Dorset line north of Templecombe transferred from Southern to Western Region LMR lines in South Wales and south-west of Birmingham transferred to Western Region1959D63xx B-B diesel hydraulics introduced (later Class 22)1960NBL B-B ‘Warship’ diesel hydraulics introduced (D833–65 – later Class 43) Evening Star last steam loco built for BR at Swindon1961D70xx B-B ‘Hymek’ diesel hydraulics introduced (later Class 35) D10xx C-C ‘Western’ diesel hydraulics introduced (later Class 52)1962Stanley Raymond Regional Manager1963The Reshaping of British Railways (The Beeching Report) published – Continuous Progress Control (CPC) computerized wagon control system installed at Cardiff, pre-dating Total Operating Processing System (TOPS) by ten years Former GWR/WR lines north of Birmingham become part of LMR1963–65Gerry Fiennes Chairman of the Western Region Board, and General Manager, Western Region BR.1965The Development of the Major Railway Trunk Routes (second part of the Beeching Report) published End of steam on Western Region – although some inter-regional trains still worked by steam1966Somerset & Dorset line closed1968End of steam on BR – Kemble to Swindon line singled1970Ownership of railway engineering works passes to British Rail Engineering Ltd (BREL)1972Bristol Parkway opened – last four ‘Warships’ withdrawn Birmingham (Snow Hill) closed1973TOPS begins to be rolled out1974Marylebone to Banbury and Birmingham Moor Street lines transferred from WR to LMR1975Last ‘Hymek’ withdrawn1976/7HST services introduced1977Last ‘Western’ withdrawn1982‘Railfreight’ and ‘Inter City’ business sectors created1985Class 142 ‘Nodding Donkey’ – Yeoman Foster GM-ED Class 591986Swindon Works closed – Network SouthEast business sector created1987‘New’ Snow Hill station opened, some previously WR lines transferred back from LMR1988Narrow gauge Vale of Rheidol line becomes first part of British Rail to be privatized BREL split between major engineering works (BREL (1988) Ltd) and mostly smaller works used for day-to-day maintenance (British Rail Maintenance Limited)1992WR ceases to be operating unit on completion of ‘Organizing for Quality’ initiative (6 April 1992)1993Railways Act (1993) paves the way for rail privatization – infrastructure passes to Railtrack1994Line ownership returned to geographical basis1996Great Western Trains (First Group), Thames Trains (Go-Ahead), Valley Lines (Cardiff Railway Company/Prism Rail) and Wales & West (National Express) franchises awarded1998Great Western Trains becomes First Great Western (FGW) ‘Heathrow Express’ electrified service operates between Paddington and Heathrow Airport (BAA)1999Midland Metro light rail system opens using old GWR route from Snow Hill to Wolverhampton2000Prism Rail acquired by National Express2001Railtrack plc collapses Wessex Trains franchise (National Express)2002Network Rail purchase assets of Railtrack plc2004First Great Western Link (FGWL) takes over the franchise formerly held by Thames Trains Chiltern Railways take over Leamington Spa–Stratford-upon-Avon franchise from FGW2006FGW, FGWL and Wessex Trains combine to become the Greater Western (GW) franchise2009Electrification of GW Main Line announced2011Chiltern Railways take over Oxford–Bicester services from FGW2014Kemble–Swindon line re-doubled2015GW becomes Great Western Railway2016Electrification of Oxford–Didcot Parkway, Bristol Parkway–Bristol Temple Meads, Thingley Junction–Bath Spa and Bristol Temple Meads, and lines in Henley and Windsor area indefinitely deferred201850th Anniversary of the end of steam on British Railways 70th Anniversary of nationalization and formation of the Western RegionThe infamous ‘Beeching Report’ published in 1963 that would drastically change the shape of Britain’s railways.

CHAPTER TWO

NATIONALIZATION TO PRIVATIZATION

SEVENTY YEARS OF PROGRESS

1948–58

At nationalization in 1948, the WR consisted of the majority of surviving ex-GWR lines, although both the system and the rolling stock was heavily run down after six years of heavy wartime traffic. Many veteran GWR locos survived into the early BR period – the last ‘Bulldog’, ‘Star’ and ‘Dean Goods’ having been withdrawn by 1951, 1953 and 1957, respectively. The first ten years saw publication of the Modernisation and Re-Equipment of British Railways (the ‘Modernisation Plan’) in 1955, the introduction of WR ‘chocolate and cream’ livery for named trains (1956) and the first of the diesel hydraulics with the North British Locomotive Company (NBL) built D600 A1A-A1A ‘Warship’ Class in 1958, followed by Swindon’s own B-B ‘Warship’ (D800–32/66–70), later Class 42.

1958–68

A decade later, the ex-Somerset & Dorset Joint Railway (S&DJR) lines north of Templecombe had been absorbed into the WR. The Somerset & Dorset had been a constant thorn in the side of the GWR and the WR would ensure complete closure before the end of the decade. Other regional boundary changes saw previously LMR lines in South Wales and south of Birmingham absorbed into WR territory. The less than satisfactory D63xx B-B (later Class 22) hydraulics arrived on the scene in 1959 followed by the NBL built B-B ‘Warship’ Nos D833–65 (later Class 43). By 1960 the last steam locomotive to be built for BR had been turned out at Swindon, and the following year saw the introduction of the first ‘Hymek’ and ‘Western’ diesel hydraulics. The Reshaping of British Railways (‘Beeching Report’) was published in 1963, the second part – The Development of the Major Railway Trunk Routes – followed in 1965, the year the WR became the first BR region to officially eliminate steam traction. It was also the year that British Railways ‘lost its way’ – becoming simply ‘British Rail’.

1968–78

Two decades after nationalization, steam had been totally eliminated from the national network, leaving the Vale of Rheidol as the only BR line left operating under steam traction, although by now transferred to the LMR. On the WR, the diesel hydraulic era would draw to a close by the end of the decade, Class 45, 46, 47 and 50 diesel electrics eventually dominating services. Bristol Parkway became the first of a new generation of ‘park and ride’ stations on the network, and the new computerized TOPS system was rolled out nationwide, starting in the Penzance area on the Western Region. The line from Marylebone to Banbury and Birmingham (Moor Street) became part of the London Midland Region, but perhaps the most revolutionary change was the introduction of the 125mph (200km/h) High-Speed Train (HST), the first sets operating on the WR, replacing locomotive-hauled services on the Bristol and South Wales routes from 1976.

The WR in the blue diesel era on Aberbeeg – the Scale7 layout of Simon Thompson – seen in the surroundings of Swindon’s STEAM Museum in 2013.

1978–88

The newly introduced HST power cars had a revised version of the BR livery with ‘Inter-City 125’ branding. By 1982, ‘InterCity’, along with ‘Railfreight’, had become two of the newly created business sectors as the gradual move towards rail privatization began. Four years later, the successful ‘Network SouthEast’ business sector was also created, but in the same year, the Swindon works – the ‘factory’ that had been the heart of the GWR and WR – closed. After fifteen years since the GWR station closed, the decade also saw the opening of the new Birmingham Snow Hill station, whilst the narrow-gauge Vale of Rheidol line became the first part of BR to be privatized.

Built from 1984 to 1987, the BREL class 150 2-car DMUs saw out the last days of the WR as an operating unit of BR. Bachmann produce accurate models for N and OO gauge, this is their 4mm class 150/1 in Arriva Trains Wales livery complete with passengers.BACHMANN EUROPE PLC

1988–98

Some forty-four years after nationalization, on 6 April 1992, the WR ceased to be an operating unit of BR with the completion of the ‘Organising for Quality’ initiative. The 1993 Railway Act opened the way to complete privatization, and infrastructure passed to a new organization – Railtrack. Three years later, Great Western Trains (First Group), Thames Trains (Go-Ahead), Valley Lines (Cardiff Railway Company/Prism Rail) and Wales & West (National Express) franchises were awarded. By the end of the decade, the electrified ‘Heathrow Express’ service was operating between Paddington and Heathrow, and Great Western Trains rebranded themselves as First Great Western (FGW).

1998–2008

The decade began with the opening of the Midland Metro over the old GWR route from Snow Hill to Wolverhampton. One year into the new millennium, Railtrack plc collapsed, all assets eventually being taken over by the newly created ‘arm’s length public sector company’ (nationalization in all but name) Network Rail. In 2006, FGW, FGWL and Wessex Trains combine to form the Greater Western (GW) franchise.

2008–18

Some seventy years after the GWR investigated electrification of part of its routes, in 2009, the government announced plans to electrify the GWML from Paddington to Bristol and South Wales. However, by 2016, electrification of Oxford– Didcot Parkway, Bristol Parkway–Bristol Temple Meads, Thingley Junction–Bath Spa and Bristol Temple Meads, and lines in Henley and the Windsor area were deferred. Finally, completing the circle, Greater Western announced that from 2015, they would become – Great Western Railway!

The Gloucestershire Railway Society organized frequent trips to Swindon, in the 1950s and 1960s, and here members enjoy a guided tour of the footplate. The regulator and other driver’s controls can be seen on the right of the cab.JOHN EMERSON COLLECTION

THE ESSENTIAL WR

With its distinctive way of doing things differently, long ingrained tradition and more than a century of history, the GWR was ‘a long time dying’. Travellers were still asked to ‘shew’ their tickets, on withdrawal several steam locomotives showed traces of their GWR livery (although probably ‘bulled up’ by crews or enthusiasts) and, well into the 1970s, the ‘old company’ continued defiantly in all but name as the Western Region of British Railways. There is, however, a lot more that made the WR so different to the other regions – from the distinctive lower quadrant signals, pannier tanks and shunter’s ‘gigs’, to diesel hydraulics and railcars. There was also the fact that ex-GWR locomotives resolutely remained right-hand drive.

Some details of the steam locomotive – taken for granted by every young enthusiast in the age of steam – may be unfamiliar to contemporary modellers. Whilst an in-depth knowledge is not essential, a basic understanding of some of the more salient points may prove useful. It is thought that in the early days of the railways, the driver was placed on the right to make it easier for firemen to fire on the footplate – you can try this at home! With small, boilered locomotives, there was little problem for the driver sighting signals, but as locos and boilers became larger, the driver’s view ahead was obstructed and the majority of railways began constructing or converting locomotives to left-hand drive. The GWR stubbornly remained with right-hand drive, even converting absorbed locomotives. Consequently, signals on the WR are often found placed on the right-hand side of the track formation to make sighting easier for the driver. It is often wrongly assumed that only GWR locos were right-hand drive, but several other railways also built right-hand-drive locomotives, including Midland Railway 4F 0-6-0s and London and North-Eastern Railway (LNER) A1 ‘Pacifics’, only converted to left-hand drive on rebuilding as the later A3 class.

BLACK AND WHYTE

Classifying steam locomotives by their wheel arrangement was devised by Frederick Methvan Whyte, coming into general use in the early twentieth century. It uses the number of leading, driving and trailing wheels, each separated by a dash, e.g. 0-6-0 (no leading wheels, six driving wheels on three axles and no trailing wheels). Using this notation, a ‘Castle’, ‘Hall’, ‘Grange’ or ‘King’ class locomotive would be described as a 4-6-0 (the tender wheels are ignored). The suffix ‘T’ indicated a locomotive with side tanks, ‘ST’ (saddle tank) and ‘PT’ (pannier tank) as in 0-6-2T or 0-6-0PT. Some wheel arrangements acquired descriptions mostly of American origin – those most commonly used on the WR being ‘Prairie’ (2-6-2), ‘Mogul’ (2-6-0) and ‘Pacific’ (4-6-2).

Under the Whyte system of notation, ‘Manor’ class No. 7800 torquay manor is a 4-6-0 – four bogie wheels, six driving wheels and no trailing wheels. The locomotives on either side of the ‘Manor’ are classified as 0-6-0PT – i.e. no leading wheels, six driving wheels, no trailing wheels and fitted with pannier tanks.JOHN EMERSON COLLECTION

LOCO CLASSIFICATION AND ROUTE AVAILABILITY

UK steam locomotives were classified by their weight (axle loading) and how relatively powerful they were. A system of Route Availability (RA) based on colour-coded routes was devised by the GWR showing the maximum axle loading permitted by the civil engineer, imposed mainly due to weight restrictions over bridges along the line. In essence, this meant that only the lightest engines were permitted on relatively lightly laid branch lines, whilst the heaviest locomotives were only allowed over certain main-line routes.

The RA code took the form of a 4½in diameter coloured disc positioned 8in above the number plate on the cab side (apart from ‘uncoloured’ engines). The system was perpetuated by the WR, also being applied to those BR Standard types allocated to WR sheds (RA disc positioned below the cabside number), as well as diesel hydraulics and diesel electrics (positioned at various heights below the cabside number and builder’s plate). The system remained in use – or at least applied to cabsides – well into the ‘Rail Blue’ era.

ROUTE AVAILABILITY

RA ColourLocomotive Types AllowedExampleUncolouredLocomotives up to 14ton axle load1366, 14xx, 16xx, ‘Dean Goods’YellowLocomotives up to 16ton axle load2251, 44xx, 45xx, 54xx, 55xx, 57xx, Class 22BlueLocomotives up to 17ton axle load28xx, 43xx, 61xx, 73xx, ‘Manor’, City of TruroRedAll locomotives up to 20ton axle load3150, ‘Castle’, 42xx, 47xx, ‘Hall’, ‘Warship’Double Red60xx class locomotives – 22ton axle load60xx ‘King’The Blue RA disc is visible on the cab side of 7820 Dinmore Manor seen at Toddington on the Gloucestershire, Warwickshire Railway.

The RA code was also applied to WR diesel locomotives as seen on Bachmann’s maroon liveried model of class 43 ‘Warship’ D865 Zealous.TONY WRIGHT, COURTESY BRM