9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

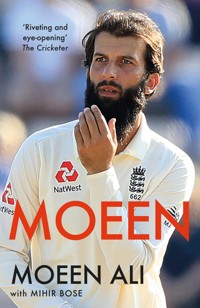

Longlisted for the Specsavers National Book Awards, 2018 Longlisted for The Telegraph's Sports Book Awards - Autobiography of the Year, 2019 Daily Mail's Book of the Year, 2018 The match-winning superstar of the England cricket team finally shares his remarkable personal story in this eagerly-awaited autobiography. Moeen traces his journey from backyard cricket to the county game and his first-class debut as a teenager, through to his international debut at the relatively late age of 27 and the golden summer of 2017, when he was anointed Player of the Series against South Africa with thousands of England fans chanting his name. But cricket is just one part of Moeen's life. His upbringing in the tough Sparkhill neighbourhood of Birmingham and the awakening at eighteen that led him to become a devout Muslim have given him a social conscience unusual for an elite athlete but have also attracted controversy. Here, for the first time, Moeen tells his side of the story. Talented, tenacious and thoughtful, Moeen Ali is a true all-rounder.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

MOEEN

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by Allen & Unwin

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2019 by Allen & Unwin Copyright © 2018 by Moeen Ali

The moral right of Moeen Ali to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

The extract from DNA India on pp. 200–202 is reproduced with the kind permission of Arunabha Sengupta.

Allen & Unwin

c/o Atlantic Books

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

Phone: 020 7269 1610

Fax: 020 7430 0916

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All images in the photo insert, unless otherwise credited, are © Moeen Ali.

Paperback ISBN 978 1 91163 014 2

E-Book ISBN 978 1 76063 549 7

Printed in

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

Prologue: The Magic of the Oval

1 Who is Betty Cox?

2 The Boy from Sparkhill

3 Chickens and Cricket

4 Not Welcome at Home

5 The Day it All Made Sense

6 The Worcester Man

7 Will England Ever Call?

8 Finally!

9 The Beard Returns to Lord’s

10 A World Cup Horror Story

11 Take That, Osama

12 The Beard Goes Abroad

13 All the Asians

14 Glorious Summer Turns Dark Winter

15 Back on Home Soil

16 An Indian Summer

PROLOGUE

THE MAGIC OF THE OVAL

As every fan knows, sport can be gloriously unpredictable – and cricket is no exception. Players, fans and media experts alike are sometimes totally unprepared for a surprise outcome. One such event was when a ‘part-time bowler’ became the first England spinner to take a Test match hat-trick for 79 years, on a ground staging its hundredth Test where no hat-trick has ever been taken. I still find it hard to believe that I was that bowler at the Oval when on the afternoon of 31 July 2017, just before 2.30, I got the South African number eleven, the fast bowler Morne Morkel, lbw. Nobody anticipated that I would make history, especially when you consider that there were two England bowlers who had had the opportunity to write themselves into the record books in that innings before I got Morkel. Both Ben Stokes and Toby Roland-Jones had taken two wickets in two balls in that South African second innings, Stokesy, the previous evening and Toby that very morning in the pre-lunch session. Now as Morkel was given out I felt like the man seen as a defensive midfield anchor scoring a hat-trick to win the FA Cup. And this when the forwards had not quite managed it. To make it even more special I had never taken a hat-trick in any form of cricket before, not even when I played for Moseley Ashfield as a teenager in Birmingham.

Before that magical moment at the Oval I had had much to celebrate on a cricket field: hundreds, five wickets in an innings, wins and even two wickets in two balls. But a hat-trick had eluded me and until you’ve actually had one you cannot imagine what a hat-trick feels like. My hat-trick also meant England won the Test, giving us a 2-1 lead with one Test to go which meant we could not lose the series and as the England team hoisted me on their shoulders I had the most amazing feeling I’ve had on a cricket pitch. I’ve never had that feeling. I’ll never experience it again.

But although I had never imagined I would take a hat-trick in the series against South Africa, I was through that summer often doing things that had not happened for a long time. At Lord’s in the first Test I had taken 6 for 53 in the second innings, giving me match figures of 10 for 112. Those were not only my career-best figures in both innings, it was the first time an England spinner had taken ten wickets in a Lord’s Test since the legendary Derek Underwood against Pakistan in 1974. At Lord’s I had also made runs: 87 in the first innings, putting on 257 for the fifth wicket with skipper Joe Root who made a quite brilliant 190. This meant I had reached a nice Test all-rounder’s landmark of 2,000 runs and 100 wickets, the second-fastest for England since Tony Greig. I’d always hoped I’d get onto the board at Lord’s as a batsman but never thought I’d be there as a bowler – it was something I didn’t expect but I’m very proud of.

As I left Lord’s with the Man of the Match award the Guardian wrote, ‘Moeen leads the team off, his body language as modest as ever. He is a pretty adorable bloke, and a fine cricketer who has finally found the perfect role in this side.’ Trevor Bayliss, the England coach, had put a bit of a dampener on things, saying after Lord’s, ‘We selected him as a batter who bowls a bit. Maybe that has taken the pressure off.’ Yet through that summer I had felt no pressure as a bowler and at Trent Bridge in the second Test my 4 for 78 in the second innings were the best figures for an England off-spinner since 1956. So, I arrived in SE11 feeling quite confident. Before the start of the Test I remember thinking this could be a series where I could be consistent with both bat and ball and make contributions to help the team win. True, we had come to the Oval branded by the media as the Jekyll and Hyde team. At Lord’s in the first Test we had crushed South Africa by 211 runs with a day to spare in Rooty’s first Test as captain. Set 331 to win, South Africa had begun their second innings after lunch but were bowled out for 119 by the close, their innings lasting just 36.4 overs. Eight days later in the second Test at Trent Bridge South Africa won by 340 runs. Chasing 474, we were bowled out for 133, our second-innings capitulation coming in less than two sessions. Anyone who has played sport at a high level knows that results are everything: you are either a huge success or a major failure. There is no halfway house. Succeed and the critics will praise you to the skies, fail and they cannot wait to bury you. After Trent Bridge critics were immediately on our back, saying they never knew which England will turn up at Tests. Would it be Dr Jekyll or Mr Hyde? This inconsistency was meat and drink to the to the former players turned pundits.

Geoffrey Boycott called our batting one-dimensional. Nasser Hussain said, ‘A positive brand is not 130 all out, that’s a rubbish brand of cricket.’ And he definitely had a point. In the warm weather at Trent Bridge Scyld Berry of the Telegraph compared our performance with ice cream: ‘on an afternoon of gorgeous heat,’ he wrote, ‘England’s batting melted away by three o’clock. They were bowled out in fewer than 50 overs as South Africa won the second Test . . . even more resoundingly than England had won the first.’ I was not spared, and, in a week, I went from being ‘a pretty adorable bloke’ to an English ice cream that melted at the first sight of the sun. The television commentators charged me with ‘throwing my wicket away’ when I was caught sweeping at square-leg in the second innings.

But despite such media criticism I and the team as a whole came to the Oval feeling far from depressed. Indeed, quite confident we could beat South Africa. You only had to see us play football in the days leading up to the Test, and even on the morning of the match, to realize how high our spirits were. The days of the double internationals have long gone – the nature of modern sport means they will never return – but the passion we have for the round-ball game has often made me think that in another age many of the present team would not look out of place at Wembley. I certainly would have loved, come September, to change from the whites to shorts and make the brief journey from Lord’s to Wembley to once again perform for England. I love football, am besotted with Liverpool and nothing would have given me greater pleasure than to run out at Wembley wearing the number nine jersey. I grew up wanting to be another Robbie Fowler. Now I fancy myself as Luis Suárez, although in the 2017–18 season I have also seen myself as Mohamed Salah. But then which Red fan has not? With the Uruguayan Suárez having used not only his feet but also his teeth I occasionally get teased, but I have never bared my fangs, not even when I am tackled by Stuart Broad, who sees himself as the defender you cannot get past. I must say our football has at times been so intense that matches have had to be stopped. To prevent injury, we play three-touch football but Jimmy Anderson and Jos Buttler, our midfield dynamos, can get so ferocious that Paul Farbrace, our assistant coach who organizes our football, often has to intervene. He has even had to stop games. Then Jimmy starts moaning so loudly about biased refereeing that I feel we could do with FIFA’s Video Assistant Referee system.

We play seven-, eight- or nine-a side football with the management always in goal. Teams are selected for a series and the best part is when it comes to choosing a side. You should see the look on Ben Stokes’s face. You cannot imagine an England cricket team without Stokesy, but he’s always the last to get picked. Unlike me and the others he is not a fanatical football man, he sort of supports Newcastle and when it comes to football he is the butt of most of the jokes. Yes, we say, you know how to kick a ball, but you cannot read a game, you do not have a clue. Stokesy does not take kindly to such ripping.

But that is all part of the fun and it helps with getting the guys going. Some days you’re going to wake up maybe a little bit more tired, lethargic or whatever. With the matches always played in the morning it peps you up and, in the run-up to a Test, it is a big thing and the most important part of the day. It’s something everybody enjoys. It also provides the dressing room banter that can be so helpful in bonding us together, even more so after a defeat with the media baying for our blood. It also brings out our eccentricities, which only adds to the fun. Broady, a Forest supporter, gets very upset if we call his team by that name. ‘It is Nottingham Forest Football Club’ he will say loudly and glare at us with the same fiercely disdainful look he will give a batsman who has just played and missed.

Paul Farbrace, the equivalent of Gareth Southgate when it comes to football, is a fanatical Chelsea supporter and I love ripping him. I also love getting stuck into our batting coach Mark Ramprakash, who in the great tradition of Middlesex players supports the red side of north London. In the last two years Ramps has not much enjoyed me asking him when Arsène Wenger will be given the push and contrasting the fortunes of the Arsenal manager with how well Jürgen Klopp is making Liverpool great again. We do have to put up with endless bragging from Jose (aka Jos Buttler), who is in love with Manchester City. But it is easier to deal with Chris Woakes, a fanatical Aston Villa supporter, and Jimmy Anderson, who loves Burnley to bits. They do not have much to talk about and the conversation about the deeds of their football teams can be short and for me rather sweet, although as the 2017–18 season progressed Jimmy did perk up.

The lead-up to the Oval Test was no different with Jimmy getting upset when Farby, as we call Paul Farbrace, stopped the game because of his tackling, Stokesy getting furious when we kept saying he is not made for football and Rooty, who supports Sheffield United and fancies himself as a striker, finding that I was bulging the net more often than he ever could. But then at the risk of sounding a braggart I am sure since we’ve been playing football I hold the Golden Boot. It was after I had banged in yet another goal in our warm-up match that I had a look at the Oval wicket the Surrey groundsman had prepared and thought it would have to suddenly change in character if my wickets tally were to match the number of goals I was scoring.

The wicket did not look as it would provide much help for spin. That is hardly surprising. We had come to the Oval a month earlier than normal, end of July rather than end of August. For much of the match there was little to make me feel I had misread the wicket. The start, of course, given our batting at Trent Bridge, was a bit anxious. But then Alastair Cook, not a great football fan – he supports Luton – and a wonderful century by Stokesy meant the Trent Bridge debacle was soon a distant memory. To finish with 353 was a good effort and that total looked even better when Toby Roland-Jones, or Rojo to his teammates, made the sort of debut we all dream about. The Middlesex bowler took five wickets in his first innings, bowling South Africa out for 175. I had little to do, bowling just 5 overs. We started batting in the second innings with a lead of 178, and with the boys not throwing away the advantage we had, I had even less to do. I didn’t even watch much of our batting. I try to watch a game as much as I can but the hardest days in Test cricket for me are the days when we win the toss, we’re batting first, and I have nothing to do. I have the biggest headache after the game if I just keep watching. I find it mentally tough and get fatigued.

To make it worse there is a huge problem when we develop a partnership because of the rule Cooky imposes in the dressing room. If we are sitting in a particular order when the partnership has begun, we cannot move. You’ve got to sit where you were sitting when the partnership started. If you want to move, you must leave the dressing room. I do get up and go to the toilet and say to Cooky, ‘Look, I don’t believe in that. If he gets out he gets out.’ But Cooky is big on this sort of thing and he will say, ‘No, you must stay there, and everyone’s got to stay in the same position.’ If the partnership is still going on then even when you go off for tea or have a drinks interval you must come back to the position you were in before the break.

So, in the second innings with the guys playing well I decided to leave the dressing room altogether and went with Saqlain Mushtaq, our spin-bowling coach, downstairs to the indoor nets at the Oval. There, while Stokesy carried on as he had in the first innings I bowled for a very long time with Saqlain.

These days sport has become so computerized that you get all sorts of graphics and data analysing everything happening on the field of play. You get stats that were just not available when I first started playing cricket. Some players like it, but to be honest I’m not a massive fan. I don’t doubt that it has its uses but it’s not for me. Probably half the England team like to look at those stats with Dawid Malan, Alastair Cook and Joe Root very fond of turning to the computer to see how they’ve done. Stats have even come into spin bowling in a big way. Commentators make much of the speed with which the ball is delivered or how many revolutions a spinner gives to the ball. I’m not bothered about checking such stats. This may make me old-fashioned but as I see it, regardless of the revolutions, if the shape of the ball is not right it might not spin.

Instead of machines I prefer to talk to humans and there is no one better to talk to than Saqlain. He is my spin guru, one of the great experts in off-spin bowling. He gets you to understand your own bowling. He provides the finest details you could ever imagine, opening what he calls ‘doors’ in bowling spin. No computer could do that. So, for example, he tells me, ‘Try and hit a good area and bowl your best bowl all the time.’ This does not mean I should bowl the doosra. That is not the advice he gives me. Just to bowl orthodox off-spin and try and hit the top of the stumps. That afternoon at the indoor nets at the Oval Saqlain kept talking to me, encouraging me by pointing out that through the summer things were getting better with my bowling.

As I practised in the underground nets at the Oval the words running through my head were my father’s: that hard work pays off and you see the rewards for working hard. I might not see the rewards now. I’ve just got to keep working hard, stay on top of my bowling. My efforts will pay off. What encouraged me further was that in contrast to previous seasons, where I had concentrated on my batting, I had never worked as hard on my bowling as I was now doing.

But as the fourth day’s play ended it seemed I would not have much to do. We had declared at 313 for 8, setting South Africa 492 to win, and at one stage they were 52 for 4, with the media speculating the match might finish in four days. But led by Dean Elgar they had recovered to 117 for 4. The papers on the fifth morning certainly saw no role for me in what was seen as an easy England victory. Much of the speculation was whether Jimmy, who had celebrated his 35th birthday on the fourth day, would get a belated present from the South Africans on the final day.

For much of the pre-lunch session I had nothing much to do and if anybody looked like getting a hat-trick it was Rojo. He had Bavuma, the overnight not out, and Philander both lbw with successive balls. But while Morris edged the hat-trick ball it fell short of Stokesy so Rojo missed out.

With South Africa 168 for 6 and the clock showing that it was not yet twelve it looked like we would win. The only doubt was cast by Dean Elgar, the South African opener, who was batting well. Indeed he got to his hundred lofting me for 4 when on 97. Then with only one over remaining before lunch Rooty brought me on. I was bowling to Morris, with whom I had had quite a few duels in the series. I remembered how he’d engineered to have me caught in Trent Bridge. The very first ball I bowled to him he edged but it hit Jonny ‘Bluey’ Bairstow on the knee. That was a near-impossible chance and Bluey would have to be very exceptional to take it. But it encouraged me that I could trap Morris. I decided that for the last ball before lunch I would try something Morris might not expect. I would not spin the ball and hope I could deceive him. That proved the case. Morris thinking it would spin played for the turn. It went straight and Stokesy, who makes every slip catch look so easy, took the catch with his customary style. He might not be able to read the moves in football but he anticipates slip catches in the way Mo Salah anticipates a defence-splitting pass and races forward to score.

As I watched Stokesy move to his left and take the catch I though how lucky I was to be playing with him. He’s a massive inspiration. He is the best cricketer I’ve played with by a mile, one of England’s great all-rounders, batting, bowling, fielding. He is also an amazing character to have around. He brings out the best in me on the pitch. This is both through how he encourages me with his advice and how he performs on the field. Sometimes he has said to me that he’ll watch me play and he’ll think, ‘I need to play like that. Or, my mindset needs to be like that.’ A lot of the time it’s the other way around. I’ll watch him play and think actually I need to be like him. That is exactly how I need to be today.

Stokesy for me is a massive player in terms of not just what he does on the field but in the dressing room. We could not be more different yet he is the best friend I have in the dressing room, a very kind, gentle guy who in private is different to his public persona. Stokesy is always coming up with ideas that bond the team together. So, during the South Africa series he had taken us go-kart racing. Although some of the players knew the sport – Jason Roy is quite brilliant at it – for me it was a new experience and without Stokesy I would never have thought of go-karting. Yes, he does have that other side where he’s very competitive but he is also a very funny guy. He likes cracking jokes all the time.

But be warned: he doesn’t take it kindly if you make jokes at his expense. So for example, if he’s playing FIFA on the PlayStation or the Xbox, where I am Liverpool and he may be Real Madrid, and if I say, ‘Ah, you know, Stokesy, you are the worst player’ or something, he will just lose it, start shouting and even tell me to get out of the room.

This lunchtime as we trooped back to the pavilion I thought it would be a good idea if the team had a laugh at Stokesy’s expense. I was ready with a joke. As we got back into the dressing room I said to the lads, ‘You are in a box. There are no windows, no doors and you have to get out of the box. How do you get out? In one corner of the box you have a saw, in another you have a knife, in the third you have a gun and in the fourth you have a hen lay.’ Stokesy, sitting in his favourite spot of the home dressing room at the Oval, had been listening to all this and suddenly said, ‘A hen lay.’ I replied, ‘Yeah,’ and he went, ‘What’s a hen lay?’ I turned round to him and said, ‘Eggs.’ Everybody in the dressing room burst out laughing but Stokesy was stony faced. He just didn’t get the joke and seeing his grim face we laughed even more. He didn’t like it at all. Now you may think such banter at lunch of a Test you want to win sounds strange but in my view it is a great bonding experience. That lunchtime at the Oval was one of the funniest times I have experienced in an England dressing room and we came out for the afternoon session in great spirits.

However, the good humour didn’t mean I had deluded myself about my performance. Despite getting Morris out I felt something was not quite right with my bowling. After lunch I bowled a spell but that did nothing to reassure me I was getting it right. Dean Elgar was batting well and there seemed no way I could get him out. There was only one thing to do. Speak to Saqlain. Half an hour after lunch, I went off and had a chat with Saqlain and as he always does he restored my confidence. He also suggested a plan to deal with Elgar.

I discussed the plan with Rooty. Elgar was still looking to drive and the plan was that I bowl wide to Elgar, get him to drive and this would trap him because I could get a bit more spin wide of the stump. The plan made perfect sense to me. The very first ball I bowled after my chat with Rooty floated outside the off-stump, Elgar obliged, went for a drive and as he edged the ball towards slip I knew he was out as Stokesy was there.

The next batsman in was Rabada. I’d had him caught at Lord’s edging to Bluey but I had actually found him quite tough to bowl to throughout the series. He is quite a solid player and he can certainly hold a bat. Being a left-hander he also gave me a different angle. I decided I would follow the same plan that had worked for Elgar. As I ran in to bowl I thought let’s see if Rabada goes for a big drive. So, I bowled almost exactly the same ball and got the same reward with Stokesy again taking the catch. South Africa were nine down. This wasn’t the first time I’d taken two wickets in two balls, but I’d never managed a third in any form of the game and now it seemed the time had come to get that elusive hat-trick. Morne Morkel, the last man, had just walked in. Yet that was the last ball of the over. And Stokesy was going to bowl the next over. So with only one wicket to fall what chance did I have?

And this is where Stokesy’s greatness as a human being and teammate came in. He had himself got two legs of a hat-trick the previous evening but failed to get the third. He was now bowling to Maharaj. When Stokesy started the over I did think he might get Maharaj out. I didn’t mind him getting him out because it would mean we had won the match. After a couple of deliveries I was pretty sure he was deliberately bowling quite wide so that I could get my hat-trick. I was fielding at point at that time. After the third ball he looked at me and said, ‘I’ll make sure you bowl at Morne Morkel.’ He ended up bowling three dot balls. After the fifth ball he looked at me and said, ‘Don’t worry, he will not get a single here. I’ll make sure Morkel stays on strike for you.’

And for Stokesy to do that meant he would have to bowl wide so Maharaj could not play the ball. Maharaj is actually a good batsman. He’s quite an aggressive kind of player, the sort who could reach and clout a wideish delivery. I must confess I was a bit anxious as Stokesy ran in to bowl those three balls, with all sorts of thoughts going through my head. Would Maharaj get a single and would I have to bowl to him? But Stokesy made sure it did not happen and I knew it was a great opportunity both for me to get my first hat-trick and for England to win the Test.

The break of an over before I bowled the hat-trick ball hadn’t made me nervous. If anything, it helped me. What also helped was that once the umpire called over, Broady came up to me, stood right in front of me and said, ‘You probably won’t get a better opportunity of getting a hat-trick than bowling to a number eleven batsman. So be clear on what you’re going to do and be convinced.’ It was not only good advice but coming from a bowler who had taken two hat-tricks for England it was also very reassuring.

Morkel may be a number eleven but he is no mug with the bat. The days when the number eleven couldn’t bat to save his life have long gone. In the first innings when I had bowled to Morkel he had taken guard on the leg-stump and played and missed a couple of balls. Then he decided to take guard on middle-and-off and suddenly he looked very comfortable. So much so that he had hit me through mid-wicket twice. But despite this I had thought I can get this guy out lbw if I bowl straight and he tries to hit me through the leg-side. However, in the first innings I never got the chance to bowl at him again.

Now as I saw him again take his guard on middle-and-leg I decided I would try to do what I couldn’t in the first innings: tempt Morkel to drive through mid-wicket and get him lbw. As soon as I put the ball in my hand and turned to bowl the constant thought in my head was try and hit the stumps. That would give me the best chance. Maybe Morkel was expecting me to bowl another ball wide of the off-stump, a slower, spinning ball. And having hit me through mid-wicket in the first innings he probably felt comfortable. I don’t know what went through his mind. As soon as the ball left my hand I knew the ball was going to be straight and when it hit Morkel’s pads I knew he was out. As I spun round and appealed I expected Joel Wilson, the West Indian umpire, to raise his index finger. I couldn’t believe it when he didn’t do so. To this day I can’t believe Wilson gave him not out. I looked at him with his arms by his side and thought, this cannot be not out. This has to be out. I can only speculate what went through his mind. I’d like to hope he was not overawed by the occasion. Maybe his heart wanted to give Morkel out but it was a big decision and he had to be absolutely sure and he was not. If that is the case I can understand it. Wilson was in a difficult situation for an umpire and didn’t want it to be seen that he was wrong.

There was never any question that Rooty, who had been at mid-off, would review the decision. With nine down if there is any sort of chance you have to take it. In any case the team was almost unanimous Wilson had got it wrong. Bluey and Stokesy had the best view and as Bluey came up to me he said, ‘Oh, that’s really close.’ Stokesy, typically, was even more emphatic, ‘That’s out.’ By this time all the players were rushing in to huddle round me, Jimmy from gully, Keith Jennings from short-leg, Dawid ‘Mal’ Malan from leg slip, Cooky and Broady. They all echoed Stokesy and even started giving me the high fives. The unanimous support of my teammates further boosted my confidence that it could not be an umpire’s call. That was the only thing that would save Morkel and deny me the hat-trick. And although as a bowler you can never be a hundred per cent sure this seemed unlikely. The decision was in the hands of the third umpire, Kumar Dharmasena, a man I knew well and who had given me a lot of bowling advice. I watched the screen as he scrutinized the television replays. However confident you are, a little shiver of fear does go through you as you watch the endless replays and you still need the three red lines to come up on the screen. I expected to see the three red lines but until they appeared I could not be sure. And when they did I felt such a surge of joy that I was a child again, jumping up and down on the pitch as the players hoisted me up. What put the icing on the cake was knowing that by getting Morkel’s wicket we had won the match and now had a 2-1 lead in the series with one Test to go. We could not lose the series and might even win it. I knew what a big moment it was. Since the creation of the rainbow nation, and the resumption of England playing Test cricket against South Africa in 1994, we had won just one series at home against them and lost the last two. Defeats against the Proteas always seem to mean an England captain losing his job. Now there was no chance of that happening. And after being like ice creams melting in the hot sun only a week earlier, the victory felt very special.

What followed our win was in some ways the most touching moment of the Oval Test and one that made me feel, and always makes me feel, how much part of this England team I had become. To the onlooker the scenes after such a victory are the usual routine ones you see on any cricket field. A Test has been won, there is a group photograph with the winning team, somebody uncorks a bottle of champagne and it is sprayed all over the players. But because I don’t drink or even touch alcohol I could not be part of any such scene. As we celebrated I could hear Cooky saying, ‘Make sure Moeen gets in the picture first and then we can spray afterwards.’ This is exactly what happened. I then walked away from the group photograph and my teammates were sprayed with champagne. The way the celebration was choreographed showed how much my teammates respected me as a person and also my culture and religion. It meant a massive amount to me. I cannot express how much I appreciated that and I felt this was a team I could give anything for.

For me the drink to celebrate with was a Coke and as I sipped one back in the pavilion it was wonderful to hear Saqlain, to whom I owe so much, saying, ‘I just knew you were going to get it.’ Even more wonderful was Hashim Amla coming to our dressing room and saying, ‘As soon as you got two and Morkel was batting against you in that position I knew you were going to get the hat-trick.’

The boys were now back in the dressing room and as soon they all started singing And so Sally can wait from the Oasis song ‘Don’t Look Back in Anger’, I knew it was time for me to go home. As the lyrics rang round an empty Oval I headed back to Birmingham. When I am driving I never listen to the cricket on the radio. Not even a single ball. I listen to lectures or talks on Islam, I listen to the Koran a lot in my car. I memorize it as much as I can. This is what I did that evening as I drove home. It makes me feel so wonderful. Wonderful as the hat-trick was, that means a lot more to me. I would later be told that while I listened to the Koran on the radio, on television and social networks the talk was all of what my hat-trick meant in the context of cricketing history. The Oval had been the home of Jim Laker, probably the greatest off-spinner in the history of the game, and Tony Lock, a marvellous left-arm-spinner – the pair that had been at the heart of Surrey’s amazing seven championships in a row in the 1950s. But, noted the commentators, they had never taken a hat-trick for England at the Oval. And while the boys thought of Sally, many commentators were now convinced the hat-trick had taken me to a new level.

Before the hat-trick there’d been a lot of interest in the ethnic media and I won awards for ethnic sportsmen. Now it was the mainstream media that featured me. Less than a week after the Oval Test the Guardian devoted nearly two pages to an interview with me. Within two months I was proudly sporting my beard in the Saturday Times magazine. I look back on that media interest and think of my little boy growing up, playing cricket for England and me an old dad sitting in a stands watching him. And if he was a bowler I could be saying to the person sitting next to me, ‘You know I got a hat-trick at a Test match.’ I had done what every kid who ever bowls wants to and aspires to do as a youngster. Even to this day I sometimes have to really pinch myself and think, well, actually I have a Test hat-trick and no matter what happens from now on, no one can ever take that away from me. The hat-trick meant I felt I belonged, had come of age at last. It’s what I had worked so hard all my life to do.

And what further thrilled me was the thought that the man who had done most to prepare me for this very special moment had witnessed it. That was my father. He had not been at the Oval but at home in Birmingham watching on television. Just before I left the Oval he and my mother had messaged me sounding very happy and proud. Soon after Donald McRae of the Guardian, who wrote the feature on me, had rung me and I had told him, ‘I am sure he has watched every ball.’ But when I finally arrived home I realized I was actually mistaken. Dad had actually not seen the hat-trick live, not been able to follow the drama of the most brilliant moment of my career. It was very sad but as he told the story to me I could not help laughing for there were some very funny moments in this curious tale.

My dad always gets nervous watching me play and I always say, ‘I can understand you were nervous watching my first Test. But there is nothing to be nervous about now.’ The Test being in London was an additional problem for him. He has come to see me play in London but as he likes to drive, not take the train, parking is always a problem. He just about manages Lord’s but the Oval is a nightmare. He can never find a parking space near the Oval. It is so bad that when he does venture into south London he has to take somebody with him to guide him around. So he decided he would watch the Oval Test on television. He was sitting comfortably in the sitting room of his house following the play on television when my wife Firuza, who was at the Oval, rang my mother to say that the gardener was coming to our house, could they go and let him in and also pay him. I was not bowling then, this was just after lunch when I had gone off the field to consult Saqlain, and Dad thought if we hurry we will be back in good time to see me bowl again. So Mum and Dad got in the car and nipped round to my house, a five-minute drive away.

Had they come straight home after that they would have seen me take the hat-trick but my mum said, ‘Let’s go to the bank, because it’s nearly four o’clock now and it’s going to shut.’ Dad reluctantly agreed and it was while he was at the bank that his phone rang and it was a call from his cousin in Karachi. He seemed to say what sounded like ‘Congratulations’ but before my dad could speak and ask him what he was on about he got cut off. The cousin does not usually ring and Dad was worried something might have happened. He decided to go outside and the phone rang. It was his cousin again. This time the line was good and he heard, ‘Mubarak, congratulations’. Not knowing why he was being congratulated, Dad said, ‘What for? What’s happened?’ Now it was the turn of the cousin to be surprised. ‘Where are you?’ he asked, quickly adding, ‘Moeen’s taken a hat-trick!’ So there standing outside a bank in Birmingham my dad learnt about my hat-trick at the Oval via a phone call from a cousin in faraway Karachi.

Dad rushed back inside the bank, pulled my mother out of the queue and said, ‘We’re going home.’ He said to the cashier, by way of explanation, ‘Moeen’s taken a hat-trick.’ The cashier stopped counting out money and shouted out, ‘Moeen’s taken a hat-trick.’ Everyone in the bank now took up the cry. My dad, holding my mum’s hand, ran out of the building, got in the car and drove straight home. As he sat watching replays of my hat-trick his phone would not stop ringing and he was flooded with text messages of congratulations. But he cannot hide his regret that he had missed witnessing my magical moment. That is a shame because without my dad and his great sacrifices, not only would I never have been in a position to take a hat-trick for England in a Test match, but I would never have got anywhere near playing cricket for England.

CHAPTER 1

WHO IS BETTY COX?

Just before the Ashes series of 2015 we went to a camp in Desert Springs in Andalucía in Spain. It is one of those classic sports camps that have developed in recent years, a sports complex in an isolated place. In winter it has ideal desert weather, warm and sunny. A lot of Premier League clubs use it for warm weather training, although unlike us they don’t play cricket. Not surprising since many of their foreign players would not know what to make of the game. We did a lot of fielding and catching practice, cycling 14 kilometres to the beach, fitness work, golf for those who are fond of the game. And we played football all the time.

But while cricket has borrowed from football, our camp was not as regimented as the ones footballers have. We were treated more like adults and encouraged to think about what was best for us. In cricket the feeling then, and still is, you are grown-ups and it’s your own career. Everyone’s responsible for his own actions. If you mess up it’s down to you. The view of the England management was, ‘We are not nannies always monitoring what you are doing.’ I agree with that approach. So, there was no curfew, nothing like that. And unlike footballers we weren’t told what to eat. Arsène Wenger, the former Arsenal manager, may have revolutionized English football by bringing in special diets to increase the fitness of players. In cricket we have never had that sort of regime. We know we need the carbs to get through a day in the field and we have to stay fit but our food is nothing like as closely controlled as that of the footballer.

It was England coach Trevor Bayliss’s first camp, an important moment and its real purpose was as a bonding exercise before the Ashes. As part of that we had to reveal facts about ourselves. One evening a quiz was organized. We had three quiz masters, Rooty was a matador, Stokesy was an Englishman abroad and Chris Taylor, our fielding coach, the Spanish golf legend Seve Ballesteros. Each of us had to give the quiz master a question which he read out to the rest of the squad. All sorts of questions were offered up by the various members of the team. My question was, ‘My grandmother’s name is Betty Cox. Who am I?’ The quiz master read out the question and asked, ‘Anybody know?’ Everyone looked at each other and you could see they were completely stumped. It was obvious nobody had a clue. Eventually the quiz master asked, ‘Nobody knows? Give up?’ Everyone nodded. The format was that at this stage you had to put your hand up, get to your feet and reveal the answer. I stood up and nobody could believe it. I can still remember the look on director of cricket Andrew Strauss’s face. He just could not believe it and still to this day can’t believe that my grandmother’s name is Betty Cox.

There are any number of England cricketers either born abroad, like Stokesy in New Zealand, or, like Straussy, born here but brought up in South Africa, but their names mean they are perceived to be English in the way I am not. In my case because of my name I am seen as a typical person of subcontinental origin who could not have any historic family connections with England. Most people cannot imagine that I’ve got an auntie called Ann who is my dad’s half sister. I’ve got an uncle called Brett, Dad’s half brother. All these relations, who could not be more English, are close family. My grandad treated Ann and Brett like his own children. My father is very close to Ann; she comes to my parents’ home every week and Ann is as much my aunt as Shah Begum, my father’s elder sister and Betty and Shafayat’s first child. I grew up with Auntie Ann and Uncle Brett and still see them regularly. I realize when people look at me and think of my origins they would never think I have a family tree which is a bridge between England and Pakistan. At times I do feel boxed in. But the fact is my dad is half English, which makes me a quarter white.