16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

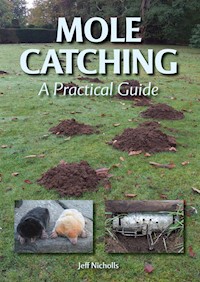

If you are a gardener, groundsman, smallholder or farmer and have a 'mole problem', then this book will be of enormous help to you. Pest-control books normally only devote a paragraph or two to moles and rarely cover the subject in detail. This volume is very different and is probably one of the most comprehensive books ever written on mole trapping. Throughout the book, Jeff Nicholls, a professional mole catcher, reveals his enormous respect for the mole and emphasizes the absolute need to control these rarely seen animals using humane and traditional methods that have been proven to work effectively. At the outset the author discusses the natural history of the mole and explains its characteristics and behaviour, an understanding of which is essential if successful catching techniques are to be applied. He then discusses in detail the traditional and humane methods he uses in different terrain and weather conditions, considers how to locate mole runs, describes all the different types of traps that can be employed and explains how to set the traps correctly.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Copyright

First published in 2008 by The Crowood Press Ltd, Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book edition first published in 2012

© Jeff Nicholls 2008

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 978 1 84797 470 9

Disclaimer The author and the publisher do not accept any liability in any manner whatsoever for any error or omission, or any loss, damage, injury, or adverse outcome of any kind incurred as a result of the use of any of the information contained in this book, or reliance upon it. If in doubt about any aspect of mole catching, readers are advised to seek professional advice.

Dedication This book is dedicated to the traditional mole catchers of the British Isles, especially those who have gone before me. With a special thank you to my wife, Angela, for her patience and understanding of the demands of living with a mole catcher.

Frontispiece: Probe to find the required run.

CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright

Preface

1 An Introduction to Mole Catching

2 The Mole

3 Catching Your First Mole

4 Catching Moles in Different Seasons and Weather

5 Mole Catching Tips and Hints

6 Commercial Mole Catching

7 Mole Catching in the Modern World

8 The Future of Mole Catching

Glossary

Useful Addresses

Index

PREFACE

Since I have been catching moles, Concorde has made her maiden flight and has flown for the last time commercially – aeronautical technology that was never bettered during her lifetime. Mole catching has also never been bettered since man first began the task of controlling this rarely seen creature. New technology has inspired many to disregard the traditional ways, but modern techniques have yet to offer an honest and respected means of controlling this common garden foe.

Many people have learned to catch moles hands-on, aided by instinct or a strange fascination for the mole. For me it has been a lengthy learning experience and there is always something new to discover. In this book, I have tried to explain the basic techniques of mole catching and the methods I use. I hope that these pages will enlighten those who wish to acquire enough understanding of moles to successfully catch them, and thus become a ‘mole catcher’.

This book will teach you ways of catching moles that will give you an awareness of your quarry, using methods that are humane and effective, and that have changed little over the years. Modern control methods are under constant scrutiny in order to avoid unnecessary suffering. When considering the methods of mole control available, be aware of the consequences of these techniques on the mole, and on the wider environment. This book is intended as a practical guide to catching moles in the most humane and effective way possible, but it also serves to warn against employing cruel and expensive control methods that can do more damage than good. In recent years, changes have been made in mole control to reduce possible suffering and harm to those persons undertaking mole control as well as to the moles themselves. These changes have left one recognized method for controlling moles, one that has been used for many years and that will still be here long after further aeronautical advances.

I wish you luck in your forthcoming battle with the mole.

Jeff Nicholls Berkshire England

CHAPTER 1

AN INTRODUCTION TO MOLE CATCHING

Mole catching as a tradition is fast fading into the mists of time because few people have the skill or ability to understand the mole in the complex world in which it lives. Others attempt and some succeed to control a mole but at what costs and circumstances? The traditional mole catcher could be seen wandering across a field or down a shady lane, a bag on his shoulder and not a care in the world. Today, life for mole catchers remains slow. With no one to correct or instruct them, only an isolated few have the knowledge necessary to be called a ‘mole catcher’. There are people who can catch the occasional mole, and it is often claimed that gardeners are as good as any mole catcher, but certain skills are necessary before one can truly earn the name ‘mole catcher’.

Mole catchers catch moles anywhere and everywhere. Gardeners catch them only in the gardens they work in, in a setting that rarely changes and in conditions that dictate little. A mole catcher will visit many locations with different features and soils, and where the general environment makes many demands on the mole. These differing, and changing, conditions will test the skill and knowledge of the mole catcher.

Nowadays, pest control companies undertake mole control, but how many in today’s profit-driven economic market can claim to offer the results and service of the traditional mole catcher? Traditional mole catchers are paid by result. Historically, ‘no mole meant no pay’ and for centuries mole catchers have had to produce a mole as proof of the completed task and to receive payment. Many of today’s disposal methods only offer a person’s word that the mole has been removed – should another mole appear there is no way of knowing if it is the same mole or a different one. Mole catching is, in my opinion, the most humane way to be rid of a mole. Mole catching employs the use of kill traps and ensures a quick dispatch of the mole. I find it strange that in today’s modern world there are so many inhumane attacks on the mole. We often proudly claim to be green and environmentally friendly. However, when a mole appears in the lawn and begins fly-tipping, the list of substances that are pushed, poked and pumped into the mole’s environment is endless, and the results are not guaranteed. The mole spends all day dodging this, squeezing past that and putting up with all kinds of obnoxious smells. Sometimes so much environmental effluent is stuffed down into the mole’s abode that it is forced to take a holiday in order to conserve energy, which will be needed upon its return to dig new tunnels in the only remaining part of the prized lawn not to have been destroyed in man’s efforts to be rid of this little man in black.

A MOLE CATCHER’S TRAPS

Mole catchers have always used traps, but I have often seen people cringe at the word ‘trap’. Traps conjure up visions of large metal devices that maim limbs and prolong suffering prior to death, but this is not the case. Traps catch by design and are authorized by the relevant authorities to carry out the task required, and only mole traps can be used in the mole environment. Many traps have been banned because they kill, maim and torture many targeted and non-targeted species, including humans. The definition of the word trap – ‘to deceive or ensnare’ – does little to change people’s perception of how a mole trap works. Perhaps if the definition were changed to ‘a quick and effective method of control’, people would find traps less repellent. It is important to remember that traps are only effective and safe when used properly.

HOW MOLE CATCHING HAS CHANGED OVER THE YEARS

Mole catching has changed little over the centuries. We know that moles plagued the Roman Empire from the earthenware pots excavated from Roman sites. These earthenware pots were used as traps. They were buried in the mole runs and part filled with water; when the mole fell in it would drown. We may never know if this was the work of mole catchers all those years ago, but the buried pot method has been used until recently around the country, possibly all round the world. I wonder how many excited archaeologists have wondered at the find of a lonely pot in the earth – a pot with a small hole in the side that would allow any fluid to escape at a measured depth. The pot required this overflow to prevent the mole from scrambling free from a naturally overfilled pot. These pots were relatively large at 12in (30cm) deep but enabled more than one mole to be caught. They were operated by a trap door in a piece of wood laid across the top, which the mole fell through when the pot had been successfully placed in a main tunnel. The mole catcher employed by the early English kings would have used this method as many of the royal estates and manors engaged a mole catcher.

An earthenware pot, once a method used to control moles.

Mole Fact File

The old name for a mole catcher is a ‘wanter’ or ‘wonter’.

Earthenware pots progressed to clay barrel traps – a tube made from coarse earthenware, which was a mixture of clay and ground-up fired pots known as grog. The traps were designed after consideration to the mole’s own natural environment – tunnels – and made from a mould. Although some mole catchers may have made their own, the local potter was always to hand. The clay barrels were made to no fixed size, and I have different dimensions for these traps from the same family of mole catchers. They were approximately 6in (150mm) in length and between 2in (50mm) and 2½in (60mm) in diameter. Two grooves cut internally at each end held snares that were used to catch the mole. Two holes in the top of the trap above these grooves allowed for a string or wire to form these snares. A third middle hole was for a peg, which was the trigger that released the trap. To enable a mole to be removed from the trap, a V-shaped cut was made to the underside of the trap body. By researching genealogical dates of the people who used these traps, it was found that the traps were used during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and long into the nineteenth century. They were the first of a series of traps that were powered by a bent stick, which I will cover later. The snares were merely a loop tied in each end of a wire or string, which sat in the groove in the trap. Another string was passed through the middle hole and tied between the snares. This allowed the snares to close and pull any mole up to the roof of the trap. The middle hole was plugged with a small peg that, with the middle string passed through, would prevent it from being pulled through unless the peg was removed. The removal of this peg by the mole was the trigger that operated the clay trap. These clay barrel traps were an advance in mole catching, but they were easily broken underfoot by both animal and man. The harsh conditions in which these traps were used also demanded a stronger material.

An original clay barrel trap, approximate date between the late 1700s and early 1800s. It displays the initials RT and was used by the Turner family from Buckinghamshire.

Another traditional village craft – that of the wheelwright – provided a solution to the problem. Cartwheels were required to withstand extreme workloads in all weathers, and soon the mole catchers were using wooden barrels to replace the weaker clay. The wheel hubs were made from elm, a timber that is strong but, more important, resilient to moisture. They were exact copies of the clay barrel in size and operation. The wheelwright – or sometimes the ‘bodger’ – like the potter could provide the body of a mole trap for the mole catcher, but the costs of these craftsmen dug deep into the mole catcher’s hard acquired money.

The wooden barrel trap soon replaced the trap of clay.

Many mole catchers began to construct their own mole traps from materials collected from the copse. These homemade traps were very similar to the metal half-barrel traps I use today. Most homemade traps were constructed from a piece of wood, two small hazel sticks, a twig for a nose peg and a length of string. The piece of wood needed to be approximately 6in (150mm) × 2in (50mm). The thickness was not important but rarely exceeded ¾in (20mm).

A homemade wooden trap.

This piece of wood formed the top or roof of the trap. Five holes were drilled in it – one at each corner and one in the middle to hold the nose peg, also known as a mumble pin. Mole catchers often added notches and their own individual marks. When I first made my own, I carved a pattern around the edge.

Hazel wood was often used because it is such a forgiving tree; the cutting promotes growth, which can be used as required. The hazel sticks were no more than the thickness, and the length, of a pencil. These were whittled down using a sharp knife to the soft centre core which, when scraped out, provided a neat groove for the string to sit in. The sticks then required bending to form the loops that would hold the strings and form the legs the trap rested on. Steam from a boiling kettle or pan was applied to the middle of the sticks until they became pliable. They could also be made pliable by soaking in water. They could then be bent slowly to form the shape of a horseshoe. A block of wood and a few nails were used to hold the sticks in this shape until they dried; some bent them round a pole. Once dry, the stick was cut to the size needed to allow the mole to pass through. This was about 2½in (60mm) for the loop and a little extra to be glued in the piece of wood when it was all put together.

The horseshoe-shaped sticks locate in the four corner-drilled holes and glue holds them tight. The string is threaded down one corner hole, squeezing past the stick, and is then pushed up out the other hole at the opposite corner. A knot is tied and the resulting loop catches the mole. The other end of the string is tied similarly at the other end of the trap. The trap then consisted of a loop of string at each end, which was laid in the natural grooves of the sticks. The string loops tied at each end of the piece of string meant that when the middle of the string was pulled, both loops operated upwards. (Some mole catchers used a copper wire instead of string to form these loops.) The finished trap now had to be powered. This was achieved in the same way as its forerunners, the clay and wooden barrel traps – with a bent stick often referred to as a bender. The bender stick was also used for powering snares for rat trapping. These sticks – often as many as three were used to power a mole trap – were approximately 4–5ft (1.2–1.5m) in length and flexible. Willow, hazel or another suitable wood was employed. Allowing for the depth of mole run the trap was to be used in, another piece of string was tied central to the string containing the two loops. A tail on the knot used to join these strings was pushed through the middle hole in the piece of wood and held in by the nose peg or – to give it its proper name – the mumble pin. At this point, the trap could be suspended by this new piece of string without the loops being disturbed. When the mumble pin was removed the string moved upwards, pulling the looped string with it.

The trap was situated in the run and held in place by further sticks cut as pegs. This was referred to as pegging and was simply a means to prevent the power of the bender from pulling the trap from the ground. These pegs resisted the constant upward pull of the bender stick(s). They were often hazel sticks cut from the tree either in a shape similar to that used to hold tents or simply a small diameter stick that was pushed into each side of the trap site walls making a bridge over the trap and holding it in place. The bender stick was pushed into the ground and bent over the trap site, sometimes resting on another Y-shaped stick like a fishing rod at the lake or river. The central string was tied to the bender stick; the mumble pin held it tight and the pegging held it down.

When the mole passed through the trap body or wooden loops and pushed the mumble pin free, the bend in the stick was released to return to its original position, pulling the string loops up with it and catching the mole. The mole was held up against the roof of the trap until the mole catcher returned or it died. The mole catcher of old would place his traps and wait patiently for a bent stick to jerk up, which indicated a catch. Remember that no mole meant no pay. These traps were difficult to use, but experienced mole catchers found it easy, which added to the mystery of mole catching.

As a young mole catcher, I would sit under a tree with a comic and soft drink waiting for the bender stick to spring up. The payment for a catch was four shillings (20p), which was a fair payment considering that other young lads received five shillings (25p) a week for potato picking.

Examples of pegging early traps in the runs. (a) Hazel was cut to form pegs or (b) bent slightly to form a staple shape and then pushed into each side of the tunnel wall. (c) An example of a bender stick.

Mole traps are referred to as being ‘set’, and this applies to them being made ready to operate in the chosen location. Old mole traps were set using a mole spud – a small square spade at one end of a long handle, about 4ft (1.2m) in length, with a metal spike fixed at the other end. The spike was used to drive a hole in the ground to hold the bender stick and to aid in locating the tunnels. The spade was used to dig the hole for the trap to be positioned into.

The length of this tool prevented much kneeling and bending prior to setting the traps. The mole spud was also used to drive a hole for any stick that was used to display caught moles. If no suitable fence or gate to display the mole catcher’s wares to any landowners was available, moles were tied to a stick driven into the ground. These sticks became known as mole sticks. Many mole or bender sticks left by the mole catchers would start to grow in damp conditions, which often explains why a willow tree can be found growing in what would be considered an unusual place for such a tree.

The clay and elm barrel traps were obviously costly in comparison to the homemade mole trap, but the wily mole catcher would have a barrel of elm cut in half to make two traps. By having a barrel cut lengthways and drilling three holes in each, one trap became two. These could still be used with a bender stick, but also with a new metal spring that could be stapled to the top of the stronger elm body. Soon they became known as half-barrel traps. The metal spring caused slightly more soil to be disturbed when used in certain depths of runs than the traps powered by a bender stick. However, the power of the metal spring meant that a caught mole was held firm, and there was a greater chance of finding a mole in a sprung trap. (The use of mole traps powered by a stick was not humane, as the mole was often left to die slowly, held by a copper wire and the force from a willow branch, but the mole catchers checked their traps regularly to reduce suffering and to retrieve the moles for payment.)

The mole spud.

The mole catchers soon sought to replace the barrel traps with the half barrels, but the problem of powering them continued to be an issue. Trap manufacturing in the United Kingdom during the nineteenth century was a very profitable industry, with new steel processing making a wide assortment of new traps available that included the metal spring powered wooden barrels but also complete steel traps.

A wooden barrel trap in the set position. Powered by the more compact metal spring, this trap has wire snares located in the grooves. When the mumble pin is pushed aside, the spring will rise, pulling and tightening the wire snares that catch the mole.

The mole catchers who used traps made from natural materials knew the mystery behind them. Only the gifted could ensure a wage from their use. The secret of these early traps was that clay and timber are porous. They absorbed any scent or smell of humans or other substances, which alerted the mole to possible danger. The mole catcher kept these traps free of human scent by handling them only after removing any sweat or moisture from their own hands with dry dirt. This ability to absorb odour may have been seen by many as a disadvantage but it also aided the mole catcher in his work, which I will explain later.