11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

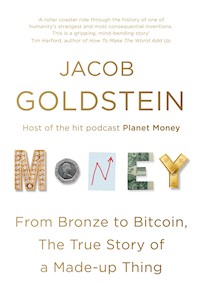

Humans invented money from nothing, so why can't we live without it? And why does no one understand what it really is? In this lively tour through the centuries, Jacob Goldstein charts the story of this paradoxical commodity, exploring where money came from, why it matters and whether bitcoin will still exist in twenty years. Full of interesting stories and quirky facts - from the islanders who used huge stones as a means of exchange to the merits of universal basic income - this is an indispensable handbook for anyone curious about how money came to make the world go round.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

JACOB GOLDSTEIN is the host of the hit international podcast Planet Money – with millions of listeners worldwide. He has written about money for New York Times Magazine and his stories air regularly on This American Life, All Things Considered and Morning Edition. He previously worked as a reporter at the Wall Street Journal and the Miami Herald.

First published in the United States in 2020 by Hachette Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Published in hardback and trade paperback in Great Britain in 2020 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © AG Prospect, LLC, 2020

The moral right of Jacob Goldstein to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

© 2014 National Public Radio, Inc. Adaption of NPR’s Planet Money episode titled ‘Episode 534: The History of Light’ as originally released on 25 April 2014, and is used with the permission of NPR. Any unauthorized duplication is strictly prohibited.

© 2015 National Public Radio, Inc. Adaption of NPR’s Planet Money episode titled ‘Episode 621: When Luddites Attack’ as originally released on 6 May 2015, and is used with the permission of NPR. Any unauthorized duplication is strictly prohibited.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 570 9

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 133 7

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 571 6

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To Alexandra, Julia, and Olivia

Contents

Author’s Note

Inventing Money

CHAPTER 1.

The Origin of Money

CHAPTER 2.

When We Invented Paper Money, Had an Economic Revolution, Then Tried to Forget the Whole Thing Ever Happened

The Murderer, the Boy King, and the Invention of Capitalism

CHAPTER 3.

How Goldsmiths Accidentally Re-Invented Banks (and Brought Panic to Britain)

CHAPTER 4.

How to Get Rich with Probability

CHAPTER 5.

Finance as Time Travel: Inventing the Stock Market

CHAPTER 6.

John Law Gets to Print Money

CHAPTER 7.

The Invention of Millionaires

More Money

CHAPTER 8.

Everybody Can Have More Money

CHAPTER 9.

But Really: Can Everybody Have More Money?

Modern Money

CHAPTER 10.

The Gold Standard: A Love Story

CHAPTER 11.

Just Don’t Call It a Central Bank

CHAPTER 12.

Money Is Dead. Long Live Money

Twenty-First-Century-Money

CHAPTER 13.

How Two Guys in a Room Invented a New Kind of Money

CHAPTER 14.

A Brief History of the Euro (and Why the Dollar Works Better)

CHAPTER 15.

The Radical Dream of Digital Cash

CONCLUSION:

The Future of Money

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

Money

Author’s Note

Money Is Fiction

In the fall of 2008, I went out to dinner with my aunt Janet. She started life as a poet (the ’60s) and wound up with an MBA (the ’80s), so she’s a good person to talk with about money. In the weeks before our dinner, trillions of dollars in wealth had suddenly vanished. I asked her where all that money went.

“Money is fiction,” she said. “It was never there in the first place.” That was the moment I realized money is weirder and more interesting than I thought.

I was working as a reporter at the Wall Street Journal at the time, but I covered health care and didn’t know much about finance or economics. As the financial world fell apart, I started looking for anything that would explain what was going on. I discovered a podcast called Planet Money. The hosts didn’t use dry, news-story language or voice-of-God anchorman tones. They talked like smart, funny people who were figuring out what was going on in the world and telling stories to explain it. I loved the show so much I went to work there.

By the time I got to Planet Money, the acute phase of the financial collapse was over, and we started looking at less urgent but more fundamental subjects. In 2011, we went on the radio show This American Life to ask the question I’d been wrestling with since that dinner with my aunt: “What is money?”

The host, Ira Glass, called it “the most stoner question” he had ever posed on his show.

Maybe! But if so, it’s the good kind of stoner question, the kind that still seems interesting in the sober light of morning. I returned to the idea of money again and again, chipping away little pieces, one episode at a time. Each little piece was interesting, but the more I learned, the more I felt like there was a deeper, richer story to tell. So I started working on this book.

Over time, I came to understand what my aunt meant when she said money is fiction. Money feels cold and mathematical and outside the realm of fuzzy human relationships. It isn’t. Money is a made-up thing, a shared fiction. Money is fundamentally, unalterably social. The social part of money—the “shared” in “shared fiction”—is exactly what makes it money. Otherwise, it’s just a chunk of metal, or a piece of paper, or, in the case of most money today, just a number stored on a bank’s computers.

Like fiction, money has changed profoundly over time, and not in a steady or gentle way. When you look back, you see long periods of relative stability, and then suddenly, in some corner of the world, money goes bananas. Some wild genius has a new idea, or the world changes in some fundamental way that demands a new kind of money, or a financial collapse causes the monetary version of an existential crisis. The outcome is a profound change in the basic idea of money—what it is, who gets to create it, what it’s supposed to do.

What counts as money (and what doesn’t) is the result of choices we make, and those choices have a profound effect on who gets more stuff and who gets less, who gets to take risks when times are good, and who gets screwed when things go bad. Our choices about money gave us the world we live in now: the world where, when a pandemic hit in the spring of 2020, central banks could create trillions of dollars and euros and yen out of thin air in an effort to fight an economic collapse. In the future we’ll make different choices, and money will change again.

These origin stories of money are the best way I know to understand what money is, and the power it has, and what we fight about when we fight about money. This book is the story of the moments—full of surprise and delight and brilliance and insanity—that gave us money as we know it today.

INVENTING MONEY

The origin of money isn’t what we thought it was; the story is more messy and bloody and interesting. Marriage and murder are part of it. So is the invention of writing. Money and markets grow up together, and they make people more free but also, sometimes, more vulnerable.

CHAPTER 1

The Origin of Money

Around 1860, a French singer named Mademoiselle Zélie went on a world tour with her brother and two other singers. At a stop at a small island in the South Pacific, where most people didn’t use money, the singers agreed to sell tickets in exchange for whatever goods the islanders could provide.

The show was a hit. A local chief attended. They sold 816 tickets. Zélie sang five songs from popular operas of the day. In a letter to her aunt, Zélie catalogued her pay for the show: “3 pigs, 23 turkeys, 44 hens, 5000 coconuts, 1200 pineapples, 120 bushels of bananas, 120 pumpkins, 1500 oranges.” But the windfall, Zélie wrote, left her with a problem.

“What to do with these proceeds?”

If she were at the market in Paris, Zélie told her aunt, she could sell everything for 4,000 francs. A nice haul! “But here, how to resell this, how to cash in all this? The fact is that it is quite difficult to hope to find money from buyers who themselves have paid in pumpkins and coconuts for the pleasure of listening to us. . . .

“I am told that a speculator from a nearby island . . . will arrive tomorrow to make cash offers to me and my comrades. In the meantime, to keep our pigs alive, we feed them the pumpkins while the turkeys and chickens eat the bananas and oranges.”

In 1864, Zélie’s letter was published as a footnote in a French book on the history of money. The British economist William Jevons loved the footnote so much that a decade later he used it to open his own book, Money and the Mechanism of Exchange. The moral of the story, for Jevons: barter sucks.

The trouble with barter, Jevons said, was that it required a “double coincidence” of wants. Not only did the islanders have to want what Mademoiselle Zélie offered (a concert); Zélie had to want what the islanders offered (pigs, chickens, coconuts). Human societies solved that problem, Jevons said, by agreeing on some relatively durable, relatively scarce thing to use as a token of value. We solved the problem of barter by inventing money.

Adam Smith had said the same thing a hundred years earlier, and Aristotle had said something similar a few thousand years before that. This theory—that money emerged from barter—is elegant and powerful and intuitive, but it suffers from one key weakness: there’s no evidence that it’s true. “No example of a barter economy, pure and simple, has ever been described, let alone the emergence from it of money,” the anthropologist Caroline Humphrey wrote in 1985, summarizing what anthropologists and historians had been pointing out for decades.

The barter story reduces money to something cold and simple and objective: a tool for impersonal exchange. In fact, money is something much deeper and more complex.

People in pre-money societies were largely self-sufficient. They killed or grew or found their food, and they made their own stuff. There was some trade, but often it was part of formal rituals with strict norms of giving and getting. Money arose from these formal rituals at least as much as it did from barter.

In the case of Mademoiselle Zélie, the local custom where she visited would have been to take the pigs and turkeys and coconuts and bananas, and throw a feast for everybody. This would have given her status—like the status people get today for paying for a new hospital wing or university library. The guests at the feast would likely have been obliged in turn to throw a feast for Zélie. Entire economies were built on this kind of reciprocity.

On the northwest coast of North America, for example, at festivals called potlatch, Native American people spent days hanging out, making speeches, dancing, and giving stuff to each other. Gift giving was a power move, like insisting on paying the check at a restaurant. Before the Europeans arrived, high-status people gave furs and canoes. By the twentieth century, they were giving sewing machines and motorcycles. This wanton generosity freaked out the Canadians so much that the government made the practice illegal. People went to prison for giving stuff to each other.

Lots of cultures had precise rules about what you had to give somebody if you wanted to marry their child, or if you had killed their spouse. In many places, you had to give cattle; in other places it was cowrie shells. In Fiji it was sperm whales’ teeth, and among Germanic tribes in Northern Europe it was rings made of gold, silver, or bronze. (Those tribes even had a specific word—wergild, “man payment”—for a payment to resolve a murder.) Rules for ritual sacrifice were often similarly explicit. In Vanuatu, a group of islands in the South Pacific, only certain pigs with especially big tusks could be sacrificed.

Once you know that anybody who is going to get married needs a string of cowrie shells, or that everybody who is going to attend the ritual sacrifice needs a long-tusked pig, you have an incentive to accumulate these things—even if you have no immediate need for them. Someone is going to need them soon enough. These objects become a way to store value over time. They are not quite money as we know it, but proto-money; they are money-adjacent. In Vanuatu, an elaborate web of borrowing and lending long-tusked pigs developed. Interest was based on the rate at which the tusks grew. An anthropologist reported that “a high proportion of the disputes and murders [were] over the payment or non-payment of pig debts.”

Money isn’t just some accounting device that makes exchange and saving more convenient. It’s a deep part of the social fabric, bound up with blood and lust. No wonder we get so worked up over it.

IOU Six Sheep

Gift giving and reciprocity worked great in small villages built around family relationships, but they were a tough way to run a city. And by the time the first known cities began to emerge in Mesopotamia more than 5,000 years ago, people had started sealing little clay tokens inside hollow clay balls to represent debts. A little cone stood for a measure of barley; a disc stood for a sheep. If I gave you a ball with six discs inside, it meant IOU six sheep. At some point, people started pressing the tokens into the outside of the ball before sealing them in, to indicate what was inside. Eventually, somebody realized they didn’t need to put the tokens inside the ball at all: they could just use the marking on the outside to represent the debt.

As Mesopotamian cities grew, power was centralized in urban temples and jobs became more specialized. Keeping track of who owed what to whom got more complicated. A class of people who worked for the temple (which functioned as a proto–city hall) figured out how to keep track of stuff by elaborating on the tokens-pressed-in-clay system. They used a reed stylus to make marks on a little clay tablet and started using abstract symbols for numbers themselves. The first writers weren’t poets; they were accountants.

For a long time, that’s all writing was. No love notes. No eulogies. No stories. Just IOU six sheep. Or, as a tablet from a famous mound in a Sumerian city called Uruk, in present-day Iraq, said: “Lu-Nanna, the head of the temple, received one cow and its two young suckling bull calves from the royal delivery from [a guy named] Abasaga.”

Silver—a metal people had used previously for jewelry and rituals—was desirable and scarce and easy to store and divide, and it became money-ish in Mesopotamia, but for lots of people—maybe most people—money still wasn’t a thing. They raised food and animals and ate what they grew. Once in a while, a tax collector who worked for the priest, or the queen, or the pharaoh, came around and took some of their barley and sheep. In some cities, the people who worked at the temple or palace also told the artisans who made cloth and bowls and jewelry what to make, and how much, then handed out the stuff as they saw fit.

The more some central authority decides who makes what and who gets what, the less a society needs money. In the Americas, thousands of years after the Mesopotamians, the Incas would create a giant, complex civilization without any money at all. The divine emperor (and the government bureaucrats who worked for him) told people what to grow, what to hunt, and what to make. Then the government took what they produced and redistributed it. Incan accountants kept detailed ledgers in the form of precisely knotted strings that recorded vast amounts of information. The Incas had rivers full of gold and mountains full of silver, and they used gold and silver for art and for worship. But they never invented money because it was a fiction they had no use for.

Money Changes Everything

For a long time, the kingdoms in ancient Greece ran largely on this kind of tribute and redistribution, complete with accountants who kept track of everything in their own specialized script. But that civilization collapsed around 1100 BC. Nobody knows why—maybe there was an earthquake, maybe there was a drought, maybe pirate raiders swept in. The kings disappeared, the castles fell down, the population declined, and the bureaucrats’ accounting script was forgotten.

A few centuries later, the Greek population started growing again. Villages became towns. A class of artisans emerged. Trade led to specialization: fancy pottery in Athens, metalwork in Samos, roof tiles in Corinth. In 776 BC, Greeks converged for the first time on a town called Olympia for a month of sporting events; the birth of the Olympics was a sign of closer ties among Greek towns, and of Greeks getting rich enough to take a month off and go hang out in Olympia.

Greek towns started constructing public buildings and shared waterworks. It was the classic setting for an economy that revolved around a system of tribute and redistribution, controlled by a king or priest, which was still common in the civilizations to the east. But instead of creating top-down mini-kingdoms, the Greeks created something new. They called it the “polis,” a word whose standard translation, “city-state,” is so boring and generic that you could almost overlook the fact that the polis is the origin of much of political and economic life in the West. Not coincidentally, it was also the place where the first thing we would recognize today as money really took off.

Hundreds of poleis developed around the Greek world, and each had a citizen assembly. In some, including Athens, the polis evolved into democracy (though, by our standards, it was a crappy democracy that excluded women, slaves, and most immigrants). In other poleis, the assembly would meet and argue, but final decisions would be made by a smaller elite.

But in every case, the citizens—the polites—wanted a say in who gave what to whom. They needed a way to organize both public life and everyday exchange without a top-down, micromanaging ruler or a bottom-up web of kinship relations. They needed money!

Around 600 BC, Greece’s neighbor Lydia, a kingdom in present-day Turkey, was mining a lot of a gold-silver alloy called electrum. This presented a kind of ancient first-world problem for the Lydians, because they had to assess the ratio of gold and silver in each piece to figure out its value. Somebody in Lydia came up with a clever solution: they started taking lumps of electrum with a consistent ratio of gold to silver, breaking them into standard sizes, and stamping the image of a lion onto each lump. So every lump of a given size had the same value as every other lump of that size. The Lydians had invented coins. Soon, they took the next step: they started minting coins of pure silver and pure gold.

Greece might have flourished if coins didn’t exist. Coins probably would have spread even if Greece didn’t exist (for the story of coins in China, see the next chapter). But coins and Greece were a perfect match, and the Greeks went wild for coins.

Standardized lumps of metal were exactly what the city-states needed to build their new kind of society—a society too big to run on familial reciprocity but too egalitarian to run on tribute—and soon there were a hundred different mints spread across Greece making silver coins. Within a few more decades, the money-ish things the Greeks had been using to measure value and exchange goods (iron cooking spits, lumps of silver) weren’t money-ish anymore. Money was coins, and coins were money.

Coins transformed daily life in Greece. Each Greek city-state had a public space called the agora where citizens gathered to hear speeches and talk about the news and in some cases have formal meetings of the citizens. Around the time coins arrived, people started showing up at the agora with stuff to sell. Soon the agora became the market—this new kind of place where ordinary people went to buy and sell cloth and figs and pots and everything else. The agora also continued to be a place for public discussion, but in the long run shopping won out over public discourse. In modern Greek, the word agora is a noun that means market, and a verb that means to buy.

Before the arrival of coins, poor Greeks would work on the farms of rich landowners, but they didn’t get anything like a wage as we would understand it. They would agree to work for a season or a year, and the landowner would agree to give them food and clothes and a place to sleep. In the decades after coins arrived, that changed. Poor people became day laborers, showing up in the morning and getting paid at the end of the day. The practice of signing on to work for a year at a time vanished. Poor workers no longer had to stay on a farm for a year; they could leave if they were badly treated or if they found a better arrangement. But no one was responsible anymore for feeding them and clothing them and giving them a place to stay. They were on their own.

People flowed into the new wage-based economy. Women sold ribbons and picked grapes, though it was considered a sign of desperation when a citizen’s wife had to work for money. When the Athenians built a new temple on the Acropolis in the fifth century, slaves did a lot of the work, but wage laborers did some of the detail finishes, like carving the fluting into the columns at the front of the temple. Because a random accounting tablet happened to survive, we know that the slaves worked almost every day, but the wage laborers worked less than two-thirds of the time. Were the laborers choosing to take time off because they preferred to do something else? Or were they denied work that they needed to survive? As the scholar David Schaps asked, was it “the blessing of leisure or the curse of unemployment”?

The spread of coins—the rise of money—made people more free and gave them more opportunities to leave the life they’d been born into. It also made people more isolated and vulnerable.

Not everybody liked what coins were doing to Greece. Aristotle complained about Greeks who thought of wealth as “only a quantity of coin,” and called getting rich in retail trade “unnatural.” Complaints like these would follow money forever, but they didn’t matter much in the end. Once coins took root in Greece, they took over the world.

CHAPTER 2

When We Invented Paper Money, Had an Economic Revolution, Then Tried to Forget the Whole Thing Ever Happened

In 1271, Marco Polo went to Asia. Twenty-five years later, he went home to Venice, bought a ship to fight in a war against Genoa, got captured and thrown in jail, and dictated a book about his travels to his cellmate, a Pisan who was a writer of popular books, including the first Italian version of the story of King Arthur. Marco Polo’s book is important for lots of reasons, but for our purposes it’s huge because of chapter 24, which has the long-but-worth-it title: How the Great Kaan Causeth the Bark of Trees, Made into Something Like Paper, to Pass for Money Over All His Country.

Polo starts the chapter by saying: This is so crazy, you’re not going to believe me. (“For, tell it how I might, you never would be satisfied that I was keeping within truth and reason.”) He was right. His story about paper passing as money seemed so absurd to people in Europe that they thought he was making it up. (To be fair, they thought he was making a lot of stuff up, and some stuff he did make up, but we know now that what Marco Polo said about money was true.) He saw in China a radical monetary experiment that appeared in the world for a moment, then disappeared and wouldn’t return anywhere on Earth for hundreds of years. What Polo saw reveals the fundamental economic miracle of an entire society starting to rise out of poverty—and how fleeting that miracle can be.

For a long time before the age of Marco Polo (really, for all of the time before the age of Marco Polo), interaction between China and Europe was pretty limited. The Chinese invented coins around the same time the Lydians did, possibly earlier, but as far as anybody knows that was just a coincidence.

Some of the earliest Chinese coins were tiny knives and tiny shovels made out of bronze, which may have been a vestige of real knives and shovels serving as money-adjacent stuff. Eventually, coins turned into small pieces of bronze with a hole through the middle. The hole let people string a bunch of coins together to make it easier to carry them. This was useful because the value of coins was based on the value of metal they contained, and bronze wasn’t very valuable, so it took lots of bronze coins to buy stuff. The standard unit became a string of 1,000 coins, which weighed more than seven pounds.

By the early part of the first century AD, China had become a unified, bureaucratic empire. Tens of thousands of students took competitive exams to get high-status government jobs, and the lucky few who managed to land those jobs spent their working lives keeping extensive records written on silk and on tablets made of wood or bamboo. Treaties were written in triplicate: one copy for each side in the dispute, and a third for the spirits.

As record keeping proliferated, the expense of silk and the bulkiness of wood and bamboo became a problem: Chinese officials needed something better suited for all that paperwork. They needed paper. According to official records, they got it in 105 AD, when a eunuch named Cai Lun, the emperor’s “officer in charge of tools and weapons,” ground up mulberry bark, rags, and fish nets; dipped a screen into the mash; then let the mash dry on the screen. People loved paper, and Cai became rich and famous. (For a while, anyway. Eventually, Cai was accused of falsifying some financial paperwork, so he took a bath, put on his fanciest clothes, drank poison, and died.)

Printing came a few hundred years later, driven in part by the spread of Buddhism, which prized reproducing sacred texts. Some monk who was tired of writing the same sacred text over and over and over had the truly brilliant idea of transferring the text to a wood block, carving away everything that was not the sacred text, then covering the block with ink and stamping it onto paper. The earliest surviving printed text is a paper scroll with a Buddhist prayer printed in China around 710 AD.

Now China had paper, and printing, and coins. The final step came two centuries later in the province of Sichuan. Most Chinese coins were made of bronze, but in Sichuan, where bronze was scarce, they used iron. In a world where the value of a coin was based largely on the value of the metal it was made of, iron was a terrible thing to use for money. To buy a pound of salt, you needed a pound and a half of iron coins. It would be like having to do all your shopping using only pennies.

Around 995 AD, a merchant in Sichuan’s capital, Chengdu, had an idea. He started letting people leave their iron coins with him. In exchange for coins, he would give people fancy, standardized paper receipts. The receipts were like coat-check tickets for coins. And just like anyone with a coat-check ticket can claim the coat, anyone with a receipt could claim the coins: the receipts were transferable. Pretty soon, rather than go to the trouble of getting their coins every time they wanted to make a purchase, people started using the coat-check receipts to buy stuff: the paper itself turned into money. (The merchant didn’t invent this out of thin air. Provincial governments had previously given traders paper receipts in exchange for bronze coins, but traders typically just used those receipts to avoid taking coins on long journeys; those receipts never really took off as money.)

Other merchants started issuing their own paper receipts. Inevitably, some shady merchant figured out that he didn’t need to start with a deposit of iron coins. He could just print up an IOU, go out in the world, and buy something with it. Once that happened, it was only a matter of time before someone came to trade in that IOU for iron coins and found out it was just a worthless piece of paper. People got angry. There were lawsuits. After a few years, the government took over the business of printing paper money.

For people who couldn’t read, most bills had a handy picture of the number of coins they could be exchanged for. There was usually some kind of landscape or streetscape. The bills were printed in multiple colors—text in black, landscape in blue, official seal in red. Almost always, a big chunk of the bill was taken up by a warning like this one, from a bill printed around 1100 AD: