Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Gill Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

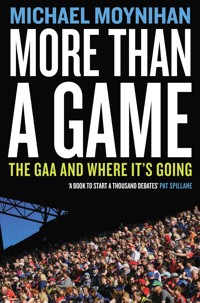

The GAA has always been about more than sport. It's the pulse of Irish communities – a shared language of identity, belonging and pride. But today, as the Association finds itself at a crossroads, urgent questions arise. Is the GAA still a grassroots, amateur movement? Or has it become a machine for elite competition, real estate development and media influence? Acclaimed journalist Michael Moynihan exposes the real forces reshaping the GAA, from under-the-table payments and controversial stadium deals to fixture chaos and the impact of pop concerts. Thoughtful and unflinching, he reveals an organisation grappling with its identity and why the outcome matters to every parish, player and supporter in Ireland. 'Michael is rooted in the GAA but never bound by it. He sees our games and Association through a unique and unflinching lens. For anyone who loves the GAA and Irish sport, this book is essential reading.' Donal Óg Cusack 'No one writes about the GAA like Michael Moynihan.' Pat Spillane

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 400

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MICHAEL MOYNIHAN

MORE THAN

A GAME

THE GAA AND WHERE IT’S GOING

Gill Books

For Marjorie, Clara and Bridget

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

Part 1: Adapting

The two (at least) GAAs

Stop, stop, stop asking former county players to referee

For the honour of the little village, and the one down the road as well

Demographics can be challenging anywhere

When three become one . . . eventually

Part 2: Revenue

Bottom lines and good timing

And not forgetting that massive bag of Jaffa Cakes

The biggest threat to the future of the GAA

Part 3: Inter-County

Four green fields and how they’re administered

GAA law: a suitable case for treatment

Why won’t people play the greatest field game in the world?

Part 4: Media

These lads have to get up for work in the morning: terrible GAA rhetoric

Slogans are (not) forever: more terrible GAA rhetoric

Cue the James Last theme: it’s summertime

Cue the James Bond theme: Sunday Game conspiracy theories

How the GAA’s attitude to the media undermines amateurism

Mute inglorious Miltons? County players speak

How the split season is not one of the GAA’s beloved zero-sum games

Being in the role model business until you’re not in that business any more

Those were the days, eh? GAAGO

Part 5: Facilities

Páirc Uí Chaoimh, or an end to Corkness

Build it and they will come

The secret hidden in the centre of excellence

You will respect my (local) authority – and work together

Part 6: Future

The Gaelic part of the GAA

An end to references

Speed bumps ahead. Or serious obstacles?

Fixtures don’t occur in a vacuum

Existential: climate change and the GAA

AI, a united Ireland and more challenges

Why? Because you love it

Always

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Author

About Gill Books

Introduction

Self-defeating though it might be, we begin with an acknowledgement of the best book on Gaelic games ever written.

Not this one, but Over the Bar by Breandán Ó hEithir, which strikes the perfect balance: between exasperation at the insanity often tolerated, and sometimes celebrated, by the GAA, and the genuine affection one retains for wayward family members. Ó hEithir’s clear-eyed view of the GAA’s faults coexists with his acknowledgement of its grip on the country.

The views of the Aran Island native would be interesting to hear now, given the different tensions within the GAA. The push–pull of club and county, the challenge of competitive balance and demographic change. Rule changes and fixture scheduling vex administrators. Financial pressures coexist with the amateur status, not always to everyone’s satisfaction. The media is a consideration. So is integration. So is redevelopment of stadiums.

Some or all of these issues existed in Ó hEithir’s time, but lately they seem to be more interconnected than ever before. There are examples everywhere, but one will suffice.

Cork hosted Limerick in the second-last round of the 2024 Munster senior hurling championship. It was a massive game, with Cork teetering on the edge of elimination and Limerick keen to push them over the edge. Originally the game was meant to be played on a Sunday afternoon but it had to be moved to Saturday evening in order to facilitate preparing Páirc Uí Chaoimh for a concert; the Cork County Board was not in a position to turn the concert down, given the size of the overrun on the redevelopment of the stadium. As a result of that move the game could not be shown on RTÉ and was moved to GAAGO, which led to a storm of criticism of that platform’s joint owners, RTÉ and the GAA. Here were the component parts of the GAA intersecting: servicing the stadium debt meant a concert had to be accommodated, which meant the media coverage was rearranged, which led to a blazing fire of criticism. Ó hEithir would have enjoyed that one.

It hardly matters that many of the players and incidents he described in his book are now vanishingly remote from our own time. Ó hEithir was at games in the 1940s, which might as well have been played out between the Fir Bolg for all we recall of them, but his anatomy of the personalities and prejudices, motivations and mercenary impulses, is timeless. Over the Bar is also one of the funniest books ever written about Ireland. If you can complete the story that starts off with a lone drinker saying ‘Ballindooley my bollocks’ without laughing you may need to check for your own pulse.

To me, the book’s strength is derived from two linked elements. Ó hEithir’s subtitle tells you everything: A Personal Relationship with the GAA. Growing up on the Aran Islands at a time when radio was in its infancy, he came relatively late to the games and maintained a certain distance, which informs his view of the GAA. That leads in turn to his view of the organisation’s strengths and weaknesses. The Ó hEithir perspective on how certain teams and individuals were blackguarded out of games, for instance, is an astringent corrective to the ‘glory of the Gael’ histories, and a couple of counties not lacking in self-regard get a hefty dunt or two along the way.

This is what sets the book apart. By stressing its perspective as his own personal view, Ó hEithir was able to criticise the GAA’s hypocrisies, big and small, and isolate potential weaknesses. Along the way he pays due tribute to the organisation’s achievements but without falling into sentimentality; to paraphrase a man fonder of rugby than Gaelic games, by looking into his own heart Ó hEithir found the best way to analyse the GAA. Everyone has a particular and personal relationship with the organisation, each of them valid and not all of them rational.

And that crystallises in Ó hEithir’s account of a rugby game, not a hurling or football match. At the 1968 Ireland–Wales international the Irish forward Noel Murphy was struck by the Welsh player Brian Price, and Ó hEithir was surprised by the reaction of Murphy’s teammates or rather their lack of reaction: ‘I said to myself, there are the hard men! Now, if you were the Crusheen, Rathnew, or Buffers Alley hurlers . . .’

As an articulation of being unable to escape one’s roots despite the impulse to broaden one’s horizons it’s difficult to beat. And all the more convincing in the light of Ó hEithir’s brisk scepticism all through the book up to that point. In retrospect it’s no surprise that two years later he wrote the greatest book about Irish politics, The Begrudger’s Guide to Irish Politics, but that’s another day’s work.

In writing this book I didn’t try to emulate Ó hEithir so much as to take his attitude as an example, because a lightly exasperated affection will be recognisable to many people who regard themselves as ‘GAA people’. The best parallel may be a family dynamic; one can despair of a close relative’s many faults, but woe betide the outsider who dares lodge a criticism of the same person. The GAA’s intrinsic power – the way it grips people and how those people never really escape that grip – is a given in Over the Bar, and it remains as potent now as it was in the 1980s. Or the 1880s, come to that.

What I want to ask in this book is a simple question, which emanates from the GAA’s position in Irish life. Where is it going?

To answer that I found myself asking the contributors some combination of the same questions. Is the GAA a delivery system for elite sport at inter-county level? Is it a participation movement which enables clubs all over Ireland to get people – especially kids – to play the game? Is it a real estate company managing and operating thousands of premises? Is it a media company working with and competing against other media companies?

Is it all these things? Can it be? Or do some of those strands contradict each other? And where does integration with ladies’ football and camogie fit into all of that? All sorts of broader challenges confront the GAA too. Just as Ireland itself has issues with housing, climate change, demographics and a thousand other thorny corners of modern life, so does the GAA.

For a long time, the working title of this book came from a familiar refrain heard at my club’s annual general meeting over the years: where are we going? It’s applicable in the specific – what are we doing this year, with this captain, with this approach, with these players, with this coach? – and in the general.

Where are we going?

When I started I thought the ‘going’ part was the significant element, which is why I asked contributors about the ramifications of particular events – the GAAGO controversy, say, or the huge debt hanging over Páirc Uí Chaoimh. Their significance for the organisation at large, and the country as a whole, seemed the important element to focus on.

Now I’m not so sure. After a lot of talking to people with a lot to say, the ‘we’ part of that sentence became more and more central to everything. Because if I learned anything at all, it’s that this is more than a game.

Part 1

Adapting

The two (at least) GAAs

I started by chatting to Tom Ryan, Ard Stiúrthóir (director general) of the GAA, who didn’t blink at the prospect of some fundamental questions, and there are few as fundamental as the most obvious of all: What is the GAA for?

My opener with interview subjects was to offer them a choice. Is the GAA a delivery system for elite sport at inter-county level, or is it a mass participation movement? Is it a real estate undertaking that manages and maintains stadiums and club grounds all over Ireland or a media company dealing with GAA+, RTÉ, TG4, online and print outlets, radio stations? All of those? Some of them?

To give Tom Ryan his due, he got to first principles pretty fast.

‘I’m sure there were the same existential issues in the past. I can only imagine the period of independence and the Civil War or the Emergency. The Troubles was another challenging time. There’s always something external to the GAA that is a “threat” but then you look at the calibre of the people and the strength of the movement and the good will that there is behind it and the heritage. We’ve been able to thrive in adversity in the past and we will again because of all those people, working in clubs that just get on with it.

‘So it might look different. It might be played a bit differently. It might be played in different places and might be played by different people, but as long as it’s recognisable as the GAA that’s enough for me.’

Ryan’s pragmatism on the GAA’s essence was a reasonable foreshadowing of what many contributors thought. An element of adapting and changing without bending it out of all recognition can be found at all levels of the GAA, and he pointed to a concrete example in the way clubs adapt to different challenges and circumstances; sometimes by amalgamating clubs. That can be seen as a defeat in some eyes, but as we’ll see later in this book, that’s not always true.

‘It’s a really increasing phenomenon; you see it a lot in terms of whether it’s the clubs formally amalgamating or whether we haven’t enough on our under-sixteen team this year, so we’ll fall in with the neighbours. It’s to people’s credit that they’re responding to circumstances. As an organisation, we need to: number one, be more open to that and make it easier to happen and number two, to change our thinking in terms of how things are structured – that that maybe becomes more accepted. The reason you’d be worried about that is actually the whole thing is to do with where you’re from. I don’t want to see a Carlow team made up of people from outside the county, for instance.

‘One of the great strengths we have is that a club is a solid thing. A GAA club is not easy to set up, which is maybe a bit of an impediment, but once it’s there it’s a solid thing. Other sports maybe have a different model, and it works for them in terms of being more easy to get together to play something with your friends; the downside of that is, maybe it’s a bit more transient.

‘It’s something to look at, though – if you don’t have enough people in your club to make up a team or if you’re not on the team or even if you just want to play with a few other people, that could be another use for these centres of excellence. To put on a programme two or three nights a week, for particular age groups but irrespective of clubs, so people could fall in for a game. That kind of thing has a value to it in keeping people involved. Whether it keeps people involved or stands on its own without the competitive, I’m not so sure.’

Ryan’s flexibility surprised me. The perception of the GAA as a monolithic bastion of conservatism is a tired one in any case, but the head official praising different forms of participation and advocating fluid club memberships?

He didn’t stop there.

‘We characterise things as parish rules, for instance, which have less to do with church boundaries as much as that’s how we define who we are. Parish rules have stood us in good stead for a hundred and forty, a hundred and fifty years, but the future of the country is going to look very different.

‘Does that model of a GAA fit? Woe betide anybody that tampers with any of that stuff, but we need to be thinking about it and not in the context of playing strength or fighting other counties. It’s in the context of sustainability: you look at your county structures. Is that the right way to be structured? You look at championship structures within counties – are they structured the right way? You look at the means by which fifteen people can come together to play, to represent something. Do they need to be bound by geographical boundaries that are rooted in the sixteenth century?

‘Look, does it even have to be fifteen people?’

When Ryan mentioned fundamentals, he wasn’t kidding. Even that relatively throwaway comment about the number of players on a hurling or football team brings us up against the basic principles of the GAA pretty fast. Readers will be familiar with various 13-a-side competitions around the country, particularly in areas with demographic challenges, but reducing the number of players from 15 would be a huge step for the GAA to consider. To take the playing side alone, it would open up new tactical challenges and developments; it wouldn’t be an overstatement to say the sports would change completely overnight. For the man who runs the GAA to suggest that change is staggering.

‘I think we need to be thinking along those lines. If the country is going to be different maybe we need to be different as well.

‘I don’t know if we’re really ready for that, and you wouldn’t like to get to the stage where a crisis means that we need to change things, to actually be able to respond. I think there will always be a cohort of people that want to play Gaelic and hurling. There are clubs all over the country which are fantastic resources; they take on the identity or they personify the locality. It’s the de facto social community, public hub, which in some ways is a big burden for them to bear. But there’s also a reassurance in that people know, whatever else happens, that that’s going to be there.’

Burden and reassurance. It could be a motto for the GAA. But which GAA?

* * *

Ideally those contributing to this book would have had hard positions on the questions I raised in the introduction, perhaps saying the GAA is definitively about the action on the inter-county stage; or complaining that its property portfolio is so vast that it needs to be minded carefully at the expense of everything else. Some unambiguous statement of fact would be of huge benefit (to an author, anyway). A stark declaration of the GAA’s focus would have set up some handy binaries, plenty of contradictions, duelling perspectives.

The reality was far less straightforward, of course. Elsewhere in this book a contributor picks out the GAA’s ability to exist in ambiguity as a significant advantage for the organisation. Distilling down what the GAA is – its fundamental focus – certainly proved that.

For instance, Ryan came down firmly on the side of participation.

‘It’s the best thing about the GAA in a lot of ways. We use this term all the time, how we’re unique. We’re not really unique in a lot of respects, but that is one of the things that is special about it. Whether it’s tennis or soccer or whatever, participation is the lifeblood of those too, but I’d like to think anyway that [GAA participation] does get a profile and a primacy in terms of people’s thinking. The number of eight-year-olds that are playing hurling around the country, that’s something we do take pride in.

‘And it should drive the decisions that we’re making. Now, it doesn’t all the time, I know that, I know other things from time to time can take precedence, but if you’re talking about what you want it to be like in fifty years – and that’s the bit that is worthy of protection, worthy of promotion – then that’s the bit that really does define the state of the organisation’s health.

‘And it isn’t – though I might regret saying this – about the number of people that are watching the All-Ireland final. It’s not the number of countries that the game is played in. It’s the youngsters. That’s a trite thing to say, but it is the truth that they are the people that will be playing senior club hurling in fifteen years’ time, they are the people that you hope will be taking teams in thirty years’ time and will be county chairperson, club secretaries. There’s an organic aspect to that which I’m not sure applies in other codes or sports. With some the sense that you get that there are key families or maybe key geographic areas that perpetuate them. With ours we’re very fortunate we have something far bigger, and that’s the bit to protect.

‘If you were to talk about primacy – and anytime you do that you run the risk of offending somebody – the bit that sets the pulse racing and the bit that you’re getting excited about is, say, Patrick Horgan coming on to get a point for Cork, and that’s great. But the bit that’s serious for the future of the GAA is the participation element. And commercially that’s the bit that is of interest to people. Obviously not every team is going to be at the business end of the championship, so not every county, when they’re going looking for sponsorship, can say to a business, “Well, you know, there’s a good chance we’ll be organising a homecoming in conjunction with yourselves at the end of the championship.” In fact, most counties can’t do that. But a lot of commercial enterprises are not really that interested in that anyway; it’s nice to have, but it’s the impact in communities, that community reach and profile, and the positive aspects of all of that which is attraction to companies now.

‘I know that also kind of runs the risk of undermining it a little bit when you make those associations, but it is fair to say that there’s a value far beyond the commercial. I mention that in the sense that it’s interesting to see that other people with maybe a different perspective from ourselves, or different things that are driving them from ourselves, see the value in that.’

Ryan’s points were well made, and he didn’t shy away from taking a position. Flying the flag for participation as the GAA’s bottom line was unambiguous, and he made a good argument that other elements of the Association’s mission flow from that.

Tom Parsons, CEO of the Gaelic Players Association (GPA), also gave his view on priorities in the GAA. By representing inter-county players the GPA has often been a lightning rod for criticism within the GAA, to put it politely. Its fiercest critics see it as undermining the GAA’s ethos by separating elite players from the rest of the GAA and absorbing too many of the GAA’s resources in funding schemes. The GPA counter-argument – which Parsons articulates elsewhere in this book – is that the inter-county game generates the funding and inter-county players deserve the best support in doing so.

Parsons started by saying that there are ‘two lines of organisation in the GAA that do two very different things for the most part’.

‘For a long time everything was merged into one but I think now we see two different realities, nearly a two-tier GAA. The first – I’ve seen it first hand – is the heartbeat of the GAA, the 2,200 clubs. What’s unique about Ireland, it’s protecting small towns, keeping kids in small towns . . . I’ve seen that myself in Charlestown. A clubmate of mine died and the town got together and the local club raised nearly one million euro in his name, built facilities, the pitch is in his name and kids can go there. I’ve seen that, whether it’s my parents doing the club lotto, people fundraising, the club players coaching kids. You can’t measure the impact and it’s grounded in voluntarism, in community spirit, it’s not just sport. If you don’t play you can join a committee, if a kid gets sick a GoFundMe page is started, all of that. For the most part that’s self-sufficient. I know there are the odd applications for capital grants and so on, but for the most part it drives itself, it’s very special. People are treated equally; that community, it’s fantastic.’

And the second?

‘The other part of the GAA, which I’m in the middle of, is the inter-county piece, and in a lot of people’s eyes, who may see the good in the GAA, they see the inter-county part as a problem child. It doesn’t have the same feel of voluntarism. Take All-Ireland final day, which has 82,000 people paying a minimum of a hundred euro each, and in the run-up to that tickets are used by many clubs for fundraising so people can end up paying, indirectly, up to a thousand. Programmes cost money, players have jerseys with three different sponsors, it’s broadcast around the world – this is serious business, and it’s special as well. This is the best of our club players representing the county, and it’s still amateur, there’s a lot of voluntarism going on as well – but it’s also different.

‘And this is where the human spirit kicks in. We’re not designed to slow down but to get better, to improve, to get bigger and faster. Everything evolves, right down to your smartphone. It’s very hard to stop that and say, “We need to go backwards.” That’s true of sport, where there’re new ways to do things, new ways to train, to improve facilities, to market the games better. The curve is always going one way. And I know these are questions rather than solutions, but you have to ask about the inter-county game, whether it’s a different type of amateurism and of voluntarism. There’s a huge amount of professionalism needed to run that, and that won’t be pulled back either. If that were pulled back the sports might never leave the island – they might not achieve the status of Olympic sports, for instance, while the GAA units serving the diaspora might not reach their potential.

‘Those are questions we need to ask – where does it go?’

Parsons teased that out further with reference to reality and revenue.

‘Where it has gone already, year on year we have huge spending on inter-county teams. Largely every manager and backroom team are all paid. There’s a handful of volunteers. There are 152 staff paid centrally who are paid in the realm of thirteen million annually according to the GAA’s accounts – all professional people in financial, marketing, IT and commercial roles. They’re in their roles to do better, to find better ways of doing their jobs in facilitating the GAA.

‘At county level you’re looking at organisations with P and L (profit and loss) of two million, three million per year. The county chair is a voluntary position but some counties now have professional CEOs, and to do this right – to be compliant – that’s needed. When the GAA does its economic report on the amounts generated by county, provincial and central means it equates to 254 million. That’s very big business and it doesn’t even take into consideration the club piece.

‘What the GPA is grappling with as a player representative body is that these players are in both worlds. For half the year they’re involved in voluntarism, the local club, being local volunteers and coaching sessions themselves, being the face of the club for fundraising – voluntarism to the core. For the other half of the year you’re still an amateur and a volunteer but you’re also asking, “Hold on, is everybody a volunteer here the way everyone in my club is a volunteer?” And that may not be the case at inter-county level. At the club level a coach may be someone’s dad, but at inter-county the coach is more likely to be a seasoned campaigner who’s well compensated. Food after training at inter-county isn’t ham sandwiches being pulled together by the parents in the club but a catering company – professionals again.

‘The players are looking at that. And they’re saying, “Of course we want to be amateurs,” but they’re also asking why, in this two-tier system, so many people are professionals but players are amateurs and at a cost? To be an amateur anything there’s a cost. Of course there is. If you take up tennis tomorrow you have to buy the racquet, lessons, membership – of course it’s going to cost you. What players are grappling with now is whether it should cost them to be in tier one – and of course it should, because we’re all volunteers – and tier two, where they’re not so sure it should cost them. The system for a lot of people in tier two is not one that costs them but actually provides them with a career and a profession. We’re at a stage now where players in tier two are saying, “Of course I’ll be amateur but I need to be well looked after and not at a cost.”’

The proof of that is in the experience of inter-county players, he added.

‘For instance, if a player on an inter-county panel is a student, playing in Croke Park or wherever on a Sunday, there’s not a hope in hell he can hold down a bar job on a Saturday night for pocket money. So a student bursary needs to be designed so he’s not at a cost.

‘If the government recognises professional sportspeople with tax breaks, the economic return of these games needs to be recognised. That means recognising the referees, the county board chairman, as well.

‘How do we look after the two-tier system without it being exploitative? If we don’t do that, we can’t continue with more sponsors on the jerseys or raising ticket prices. Every year the revenue increases but so do the demands of an elite game. We need to look at how we increase the value proposition here and make sure it doesn’t cost players. Particularly when the next generation of players might not be the same stoics we’ve seen in the last few decades. Who mightn’t be willing to forego the weekend work as a student to play for the county. We might not see the old twelve-year commitment of a player to the county team, and more of a continued churn of players; we might lose the role model aspect of the games. So we’re at a delicate stage in terms of that balance.

‘Can we roll it back? Back to the ticket prices of the early noughties, to straight knock-out, to the time before video analysis? I doubt it. The sponsors and commercial partners aren’t going to back that. Neither are costs such as stadium maintenance. So we modernise it, recognise that a large part of tier two is big business, recognise amateurism but accept that what applied in the eighties and nineties won’t work in the 2040s, for instance.

‘Amateurism is not dying at the club level. Not at all. But at inter-county level it’s dying.’

What’s interesting is that both Toms, Ryan and Parsons, acknowledge the amount of moving parts involved in the GAA. Ryan stressed the importance of participation but pointed to the attractions of the inter-county game; he freely admitted that other things take precedence at times, a simple statement of fact. Parsons’ focus on the inter-county game was understandable, given his role as head of the GPA (and there are plenty of GAA people with a reflexive dislike of the player organisation on the grounds of elitism). But the former Mayo footballer began by stressing the importance of the club ethos and delineated its significance precisely. Again, a statement of fact.

Interestingly, some other comments from the two men reverberate elsewhere in this book. When Tom Ryan mentions the commercial attraction of the game being linked to what it stands for, that’s an idea that gets teased out when discussing Páirc Uí Chaoimh’s sponsorship travails.

Tom Parsons’ comments on the level of interest future inter-county players may have in the game finds an echo in Dara Ó Cinnéide’s thoughts on the meaning of representing one’s county.

Parsons’ aside about management teams – that most of them are paid – may be the best segue to discussing one of the greatest hypocrisies in Irish life, never mind the GAA or even sport on this island. How are managers being paid secretly in a game that proclaims its amateurism and volunteer ethos so loudly? Well, we’ll come to that.

First, though, why is the support so poor for people who should be paid well for what they do for the GAA?

Stop, stop, stop asking former county players to referee

It never ends for referees.

In hurling, even as this book was being written, the Cork County Board was protesting ever so loudly that it had no issue with how referee Johnny Murphy had handled the All-Ireland senior hurling final. But it also acknowledged that it had sought clarity from him after the game about an incident that had occurred on the field of play. And Gaelic football referees were juggling with an array of new demands introduced by the Football Review Committee’s tinkering with Gaelic football rules.

When I spoke to Barry Kelly, one of the most experienced GAA officials around, I asked where he thought Gaelic games refereeing was in general. He soon got specific.

‘I read Owen Doyle, the rugby referee, this year commenting on the quality of rugby refereeing, and he was saying there are good refs in Ireland and good refs in South Africa, but they can’t take Ireland–South Africa games, so then you’re looking at other countries’ refs and wondering how good are they . . .

‘I don’t think we’re a million miles from that scenario insofar as in inter-county hurling, say, there may be twelve referees on the championship panel but six or seven may not have a huge amount of experience or may not be eligible for a game, depending on which counties are playing. And some of those may not even be involved in five years’ time anyway. It’s a similar situation in football, where there has been great service given by the likes of David Coldrick and Joe McQuillan and a few more, so I would be concerned.

‘In Leinster in particular there is a dearth of young referees coming through to push on to the next level, lads in their mid-to late twenties. Because that’s what you need to do, really, to almost sacrifice the playing career for refereeing. Take Leinster as an example. You break through from the club to the provincial refereeing panel, maybe four or five years on the Leinster panel then before you break through to the national panel. If you’re to get ten years out of a referee on the national panel then he’s got to be there at thirty-four, thirty-five years of age, maybe – and to do that he’s got to have ten years’ refereeing behind him at least. So where do you fit playing in around that?’

Support for referees is vital and could be improved, he added.

‘As far as I can see there are two people employed full time in Croke Park looking after this [refereeing] but I’ve seen references to 350 GAA coaches being employed. That means millions are being spent on coaching, which I obviously don’t have a problem with, but in a way you really need to be employing referees, even on a part-time basis.

And employing support for them. Say a referee has a tough day – he makes some controversial calls and there’s a lot of focus on him. There should be someone employed by the GAA who can say, “Hey, Johnny, I’ll be in your neck of the woods this week and I’ll bring you to lunch and we’ll have a chat about the game. We’ll work through it and discuss it.” It doesn’t need huge money – you could have someone retained on twenty grand a year part time to do that.’

Looping back to getting people involved as referees, the usual line is ‘we need more former players taking up the whistle’, but Kelly isn’t long-skewering that notion. There was a time in the fifties when Peter McDermott might be lining out in an All-Ireland for Meath and refereeing an All-Ireland final a year or two later, but those days are long gone.

‘That thinking fails to account for the reality, really. Imagine going up to a player after he’s finished up, at maybe thirty-three or thirty-four years of age. At that stage he has probably been involved in serious sport for twenty years with underage, schools, colleges, club and inter-county. At that point in his life he’s probably in a serious relationship, possibly with a couple of kids, and his work situation may be progressing to a stage where he has more commitments and responsibilities. Imagine that player turning around to his partner or wife and saying, “I’m going to throw my hat in the ring as a referee now. There’s a fair bit of commitment involved.”

‘And there is. Two-hour journeys, games, bite to eat – you could be gone eleven hours, so the idea of the former players taking up the cudgels . . . I don’t see it happening because in fairness, they’ve given their service to the GAA.’

That leads to counties getting creative in enticing people to take up the whistle.

‘In Westmeath we run refereeing courses and every year there are the same exhortations to clubs, “We need referees” and so on. I’m the Westmeath minor board chairman and last year we almost coerced clubs that are at under-twelve level: we said, “If you don’t supply a referee at under-twelve level you don’t get home games under twelve.”

‘So we had about seventy-five guys that did the course but it was an unnatural figure, thirty-three of them have actively taken a match so far. Most did the course to get around the issue we presented – though on the other hand we did have thirty-three referee a game, which is great. Still, how many of them will continue? We had to use a stick and carrot approach, and it was mostly stick.’

Should Croke Park be following that approach?

‘Some counties are going down the road of a punitive approach in the sense that [if] your club doesn’t apply referees, then you don’t get All-Ireland final tickets, or you might get fined, or you might not get home games. It’s probably a strength of the Association that there’s a reluctance to impose financial penalties, because who’s going to pay that? It comes out of the lotto account and it’s hard enough to raise money in the GAA. Clubs are under pressure as well.’

Is this all a bit of a catch-22? If referees were paid just a little more, would it just make it just a little more attractive? The GAA’s amateur ethos is laudable, but facilitating more referees would surely help?

‘A Westmeath referee for an adult club match gets fifty euro. Would more money make it more attractive? It’s a touchy one. Yes, there are a lot of referees whose primary motivation is the money, and then there are the guys who enjoy it and the money is kind of almost secondary. And there are other factors. Westmeath is a small county so you’re never travelling that far. If I went from Athlone to Mullingar for a game, which would be rare, it’s thirty miles. It’s a lot different in counties like Cork and Galway and Donegal.

‘At county level it’s different. At club level the fee isn’t based on mileage – if it was I’d get nothing half the time because I rarely travel more than five miles to a game. At county level it’s just your mileage and an allowance for a bite to eat. And that’s become very stringent, whereas before it was more relaxed.

‘Recently enough I was at a club match and the referee was there a good forty-five minutes before the start so he was gone a good four hours from home – he had a fifty-mile round trip. The meal allowance is €13.70, so if he made a full claim he’d have had about forty-four euro. But if he’d refereed a local club game he’d have had fifty. At inter-county level a referee could be gone ten or eleven hours, wear and tear on the car, all of that – his umpires are getting absolutely nothing, only a meal – so after everything there’s very little financial reward. The point being, he’d also be better off financially handling a local game, if finance is the motivation. And if you suddenly increased the referees allowance to ninety-five cent a mile the GPA would be hot on your heels as well.’

This is a point worth noting, of course. The GAA is no more a monolith marching together in lockstep than any other mass movement. There are plenty of sectoral interests keeping a close eye on funding allocations and budgetary commitments; in fact, the GPA might not be the only interested party when it comes to increased mileage rates.

On top of the financial consideration, the time commitment is hugely significant, Kelly pointed out. Driving to and from a game is only the start.

‘Take a national league weekend with double fixtures, football and hurling. There’s a sending-off in a football game and that county is going to want that player available for the next weekend. There’s no doubt that they’re going to appeal, so for the lads in Croke Park who have to deal with that appeal, it’s almost like preparing a court case; there’s a huge amount of i’s to be dotted and t’s to be crossed and video evidence. You can’t just go in; you have to make sure your case is prepared properly. It’s hugely time-consuming, and obviously there might be more than one appeal arising out of each weekend. All of that is alongside the appeals meetings themselves and seminars on rules and committee meetings on those appeals and seminars. Fellas like Donal Smith [GAA National Match Officials Coordinator] are at those meetings at Croke Park every weekend of games.’

There are other complications. Hawk-Eye means there are two different sets of rules for inter-county games, those with the technology available and those without.

‘There was a game last summer [2023] in Hyde Park with a very tough call, a Mayo 45 that replays showed came off a Mayo player. Colm Reape kicked the 45 and it could have been the difference between winning and losing the game. But there’s no Hawk-Eye in Hyde Park. The big hurling matches tend to have it because they’re in Thurles and Croke Park, but I’d be a traditionalist in the sense that – as we’ve seen across the water in England with VAR – has it improved things?’

Not according to Gary Lineker et al., as Match of the Day fans can attest. Kelly finesses the point, however, with the example of a different sport and brings up the spectre of refereeing to video confirmation rather than officiating to the official’s own judgement.

‘In rugby – and I’m not anti-rugby at all when I say this – it seems that unless the guy gets the ball and dots it down under the posts the referee tends to automatically go to the TV to confirm the score. The average rugby game basically lasts two hours because you have all these stoppages. I’m not entirely sure about technology in this sense. People talk about managers having the ability to challenge one decision or two, but even bringing that into inter-county senior football and hurling would still require a fair degree of technology to be implemented. You’d have to bring it into Clones and Letterkenny and Páirc Uí Rinn, all of these places. I’m not saying we should opt for the lesser option but sometimes we look directly across at soccer without taking on board that that is a global game. The figures bandied about in English soccer, in terms of television deals and attendances and club earnings and so on, those are getting into the billions. It’s different.

‘Sometimes we’re comparing ourselves to a global game played by every country in the world – every young child that has ever walked and played soccer amounts, eventually, to billions of people who’ve played or been involved with the game. Ours is very much an Irish game – it’s played by lots of people here, the diaspora enjoy it, which is great to see, but it’s still very much a local, national game.’

Which is not to say it’s immune to change. Kelly has seen the benefits of rule changes and also the way those changes can influence the very skills of the game.

‘I think changes like the square ball rule in football have been a godsend in that there are very few mistakes made. Absolutely. I was at a sandbox game [trialling] for the new football rules [and] what was interesting was the lack of two-point shots in the game, shots from forty metres. The reason was, as players pointed out, they don’t practise that skill. They’re playing one way the whole time where you hold possession until you get close enough for a shot – closer than forty metres.

‘If you take a shot from that distance and you don’t score, then at half-time that’s [put] down as you [losing] possession. But if you made a five-yard handpass, then it’s a positive outcome when the stats are examined. In football you don’t take a shot unless your best forward is twenty-five yards out on the D and he’s free.

‘It’s funny because in hurling [Limerick manager] John Kiely seems to work to the opposite plan – his players shoot all the time. In one game last year they got off fifty-one shots, and clearly if they have a success rate of sixty-six per cent they’ll outscore the opponents; and hitting the ball wide isn’t necessarily a turnover. They’re confident that they have a very good chance of winning the ball again from the opposing puck-out, whereas in football giving the ball away is a fear, because there’s a chance [that] if you lose the ball you may not see it again for three or four minutes.

‘Two referees may not be needed in football because games are so lateral, but are two referees possible in hurling with numbers? You may not be able to have two refs for a club game, but if you have two refs at inter-county, or after the All-Ireland quarter-finals, then you have two different ways of refereeing. And that would ask very different questions of teams.’

For the honour of the little village, And the one down the road as well

Amalgamation is a shadow that looms over many GAA clubs, particularly in rural Ireland.

When I wrote GAAconomics former President Nickey Brennan acknowledged that reality in the general and the specific; his club, Conahy Shamrocks, is one of the smaller outfits in Kilkenny. If it had to happen it had to happen, he said, adding that when and if it did he would probably weep for a week. That’s an outlook many GAA members will recognise: the harsh reality that muscles its way past a vague formulation.

Dara Ó Cinnéide explained it from his perspective.

‘We had our existential moment a few years back when Dingle, our bitterest rivals [Ó Cinnéide is a member of An Ghaeltacht], made a submission to us to see if we’d amalgamate with them at underage because they were struggling for numbers. There was a meeting called to discuss it but it had to be called off, so at mass the following Sunday someone said to me, “Would you show your face at that meeting because I have a feeling this thing is going to happen?” I went in to the meeting and there were over thirty people there, a lot of parents of talented footballers, and after listening to the discussions for about forty-five minutes I piped up.

‘I said that the amalgamated teams would probably be good enough to win championships and medals, but that the whole point of the GAA was our corner forward, who would lose his place if we amalgamated with Dingle because he wouldn’t be good enough for the first fifteen. Even if we won a cup we could lose players like him because he would think, “They don’t value me, so why would I bother playing?”’

Ó Cinnéide went deeper:

‘Our mistake as a club for years was to say, “We have Darragh Ó Sé playing for Kerry, Dara Ó Cinnéide playing for Kerry, we’ve won this and that.” That was never the success of it. I felt a much better spirit in the club in the early nineties when we were a division three novice team.

‘Eventually two of us convinced thirty-odd people at the meeting not to amalgamate, but of course I then had to go back to Dingle to tell them it was off – I was the blackest of the black Gaeltacht men, the man who blocked it all. I had to go to Diarmuid Murphy, Breandan Fitz, lads I knew well, and I told them this wasn’t an anti-Dingle thing, it was a pro-Gaeltacht, pro-GAA thing. It’s not that you’re not welcome, I just don’t think it’s the right thing for our club. The word “club” even suggests cliquish and clannish, and I want that borderline hatred, that rivalry, to continue. I felt that that would disappear if we amalgamated. Part of my raison d’être would vanish overnight.