50,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

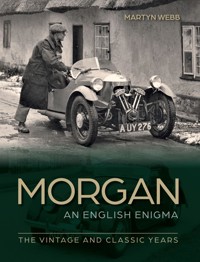

This book tells the amazing story of the Morgan Motor Company, from the primitive, but very successful cyclecars of Edwardian times, through to the iconic British sports cars of the Classic period in the 1960s. Morgan defied conventions, survived economic hardships, resisted take-over bids and carried on in its inimitable way, hand-crafting 'proper' cars out of the historic row of workshops in the spa town of Malvern. Morgan – An English Enigma takes an in-depth look at the Morgan Motor Company during the Vintage and Classic periods, benefitting from access to previously unseen documents and drawings, and featuring 500 images, over half of which have never before been published. This fascinating story will appeal to those with an interest in motoring history, the motor sport enthusiast and anyone who appreciates fine British sports cars.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 794

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Sporting Runabout, BH4473, was the personal transport of fireman Mr E.H. Ward, seen here at the Fireman’s Sports Day at Bletchley, Buckinghamshire, in the summer of 1920.

In the summer of 1957, René Pellandini of Worldwide Import Inc., Morgan’s dealer in Los Angeles, visited the factory. He is seen here with the factory management team, far right, next to Peter Morgan and Jim Goodall. On the left is George Goodall (in cap) and Harry Jones. The photograph was taken in the factory yard outside the despatch bay alongside a new US specification Plus 4.

Contents

Foreword by Charles Morgan

Introduction

1 Victorian Family, Edwardian Factory

2 Pickersleigh Road

3 The Early 1920s

4 The Late 1920s

5 The Morgan Family in the 1920s and 1930s

6 The Morgan Factory in the 1920s and 1930s

7 Three Speeds in the 1930s

8 Three Wheels, Four Cylinders

9 The Morgan 4/4

10 The Morgan Factory in Wartime

11 Post-War Recovery

12 More Power – The Plus 4

13 Re-designing the Morgan

14 The Classic ‘Cowl Rad’ Cars

15 The Morgan Factory in the 1960s

16 The Classic 1960s Morgans

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

Foreword

I was honoured to be asked by Martyn Webb to write a foreword to his history of the Morgan car and Morgan factory, or the ‘works’, as it was always known internally. Webb has undertaken a massive task, researching well over a hundred years of achievement with access to archives of company minutes, factory drawings and memos, pages of press cuttings and photographs and personal recollections. Webb has cross-referenced hours of interviews with people who were present at the time with published data to provide a balanced view of events and facts. This history is a meticulous piece of research and is sure to become the definitive history of Morgan, a company that was present at the birth of popular automotive mobility.

Of course, memory invariably involves falsification and Webb has combined personal accounts with company records to mitigate this problem. An example is the multiple differing recollections from perhaps one of Morgan’s greatest competitive successes, at Le Mans in 1962. Webb’s research provides a definitive view. But it is always difficult to fix a neutral point of view – God’s view, if you like – and some would argue that the pursuit of a determined factual truth, an orderly extension of common sense, is not the real story. As Gilles Deleuze, the twentieth century French philosopher, wrote: ‘genuine thinking is a violent confrontation with reality’. In Morgan’s case, passion generated by the company and its products is perhaps the secret of the longevity of the company rather than a dry account of models, specifications and engineering achievements. Morgan in the automotive world is unique in creating myths and stories that are perhaps only slightly based in reality. The ten-year waiting list comes to mind.

Why is this? In terms of volumes produced, Morgan should be a footnote in automotive history. Yet the company punches far above its weight in the historical record. Perhaps this is because, like Bugatti, the company is one of the few automotive examples of the human combination of art and science. Deleuze distinguished art, philosophy and science as three distinct disciplines, each analysing reality in different ways. Whereas philosophy creates concepts, the arts create novel qualitative combinations of sensation and feeling (precepts and affects) and the sciences create quantitative theories based on fixed points of reference, such as the speed of light or absolute zero. I remember Ian Minards, then chief engineer at Aston Martin, once told me that every aspect of car control is a merely a spring and a damper and variations of the same. From an engineering point of view I am sure he was right. This was certainly the case for Morgan in the 1950s and 1960s. The sliding pillar suspension system was for many owners and drivers the subject of heated discussion and passionately held views. Much of this discussion flew in the face of scientific thinking, yet it may have promoted the longevity of the company and the love of the product. Feeling often trumps reality in the car world. Throughout the history of Morgan, from its inception as a company in 1909 to the 1960s, art and to a certain extent philosophy was always incorporated into the strategy of the company. Among the diehard followers this combination bred an undying loyalty. A passion for the company was baked into all the members of the Morgan family and my sister, Sonia, proved humanity is always a winner in the marketing stakes when she became the ‘face’ of the Morgan Plus Four Plus.

Today the UK car industry faces a series of alarming problems: car production in the UK has fallen from 1.7 million in 2016 to less than 0.7 million cars in 2021; the move to electric vehicles is now a certainty in 2030. But perhaps solutions to these problems are elusive. Some of them seem to set incompatible goals – for example, the goal of agile lightweight passenger cars and cars that protect and carry a large battery pack for a long range. Cities are happily now designed above all for pedestrians and bicycles, yet deliveries to shops and restaurants still have to be made. Driverless cars spell an end to the skill of driving, yet cars with electric motors can accelerate much faster and will be more dynamic. Perhaps the greatest conundrum of all is whether personal mobility is actually beneficial to humanity or not. Apart from the horrendous cumulative total of deaths and injuries from car accidents over 100 years, a massive proportion of global warming is caused by the emissions from automotive mobility. It is time for a massive rethink on the whole issue.

The early days of any blossoming industry frequently provide pointers to the future, albeit in forms which were initially seen as dead ends. For example, there were more electric vehicles in New York in 1909 than internal combustion cars when H.F.S. Morgan built his first prototype three-wheeler. Webb’s history of Morgan presents some interesting ‘Morgan’-type avenues for the future. As Webb shows, Morgan has pioneered new design directions. The Morgan Three-wheeler brought personal mobility to the masses in an extraordinarily efficient manner, even by the standards of today. The history of the Morgan in trials and competitions was an essential component to promote reliability and test new design solutions, not a marketing exercise. Morgan tested cars in competition, notably with Prudence Fawcett at Le Mans in 1938, and to determine the reliability of the car though the fact that she was such a popular driver at the race cannot have harmed publicity for the company. Morgan also spearheaded the practice of exports to improve the balance of payments of the UK. The popularity of the Morgan two-seater sports car in the USA, following MG’s success before the Second World War, encouraged MG and Triumph to follow Morgan’s example. In the 1950s and 1960s Morgan exported by far the greater part of its annual production overseas and Triumph in particular were quick to follow after failing to convince H.F.S. (Henry Frederick Stanley Morgan) and Peter Morgan to sell them the company. Morgan stuck to its guns of hand-built production but that system, using wood from trees and the human hand to finesse natural materials, foretold the bespoke production systems of the luxury car manufacturers of today. Perhaps there are also lessons to be learnt about recycling from Morgan’s history. The restoration of any Morgan built between 1910 and 1965, the period covered by this book, is still possible in a garage next to the house with parts readily available from Morgan dealers. Morgan pioneered a low-carbon approach to the construction of personal mobility before global warming had even been thought about.

With the recent upheavals in the motor industry, Webb’s history of Morgan may be timely. Morgan was always a very human company and perhaps that is why it is beloved by so many owners and those who may not even have had the opportunity to own a Morgan. Webb’s story might help explain this phenomenon. Webb’s copious history of Morgan cars illustrates many examples of a human approach to automotive engineering problems. This lesson may be a timely one in an age of artificial intelligence and the approach of a singularity derived from vast amounts of data. Science and AI can suggest solutions, but humans have to ask the right questions. A digital data-driven solution may not be the best one for humanity. As Webb shows, Morgan has provided us with solutions and answers to questions in the past that were made before the ubiquity of data-driven solutions. This, rather than the volumes of cars produced, may be why the history of Morgan is important and could have lessons for us all.

CHARLES MORGAN

Introduction

Morgan is a paradox of the motor industry! For well over a century, this small family-run concern has been handcrafting anachronistic vehicles from a row of timeworn workshops in rural Worcestershire. It has survived two World Wars, the great economic depression of the 1930s and numerous other financial troubles. In the early years, the factory persevered in building three-wheeled cyclecars when three-wheelers were seriously out of fashion and the cyclecar as a genre was extinct. For most of its subsequent history, Morgan was alone in persisting with traditional styling superimposed on a wooden frame, when all other manufacturers were embracing streamlining and aerodynamics, unitary construction, modern materials and mass-production.

Industry experts have predicted Morgan’s demise with monotonous regularity and the perceived wisdom has often been that the company could not possibly survive in competition with the big manufacturers. Yet survive it has, confounding the experts and delighting devotees around the world who appreciate classic sports cars. How it has achieved its fame and longevity when almost all other small companies have been consigned to history is mystifying. Morgan is, quite simply, an enigma!

Shy and introverted, the founder of the company Harry Morgan was a maverick, never following convention in the pioneering days, but sufficiently confident in his engineering expertise to go it alone and build vehicles that were neither cars nor motorcycles. The Morgan Runabout was the original ‘cyclecar’, a machine that launched the ‘new motoring’ fashion, and introduced motoring to those of more modest means. When the ‘cyclecar’ met its inevitable end, Morgan fell in line with other makers, with a conventional sports car that did not simply match the opposition but, more often than not, proved superior on both road and track. Not content to just build the cars, Harry Morgan proved their performance and strength in numerous reliability trials and was widely regarded by his peers as one of the finest competition drivers of the day.

Peter Morgan was very similar in character to his father. This quiet, astute man shared the same instinctive appreciation for simple, but effective engineering. His army officer training provided him with the requisite managerial skills, making him a very popular boss to his employees, whilst being very effective in having to contend with an ever-growing threat from the mainstream, mass-production industry. Such was the reputation and respect that both father and son enjoyed, that they were able to negotiate major contracts for engine supplies from the big manufacturers. The Morgan Motor Company may have been a small concern, but it was held in high regard and in all other respects it was the equal of the very best in the business.

Since the company’s centenary in 2009, I have been privileged to work at Pickersleigh Road and to play a very minor part in Morgan’s recent history. Much has changed in the past dozen years, yet the factory and its cars remain unique in the modern motor industry. Today, the visitor centre welcomes many thousands of guests each year to experience the build process and to have the opportunity to drive the cars. The Plus Four and Plus Six models retain the handsome styling of the classic models from the 1960s, yet are underpinned by the very latest bonded aluminium chassis technology and powered by modern generation 4- and 6-cylinder BMW turbo engines. The three-wheeler has also seen a renaissance, initially with a V-twin engine, and more recently the ‘Super 3’, with an in-line 3-cylinder Ford engine (a modern equivalent of Harry Morgan’s F-Type of the 1930s).

Nothing quite matches the driving experience of a Morgan, combining impressive power delivery with extraordinary levels of roadholding and handling whilst retaining the enjoyment of open-top motoring. Morgan’s present-day success is the culmination of decades of innovative engineering, skilled craftsmanship and impressive motor sport achievements. Morgan – An English Enigma examines the background to this extraordinary company, and the circumstances that resulted in the remarkable survival of an icon of British motoring.

Martyn Webb

Malvern

September 2023

CHAPTER ONE

Victorian Family, Edwardian Factory

Mechanised Transport in Queen Victoria’s Reign

The freedom to travel extensively is something that we take for granted today, but for centuries this was an unattainable dream for all but the wealthiest adventurers. Ordinary folk seldom strayed far from the villages and towns of their birth, so both local journeys and more distant travel relied upon human or animal muscle or the somewhat unreliable power of the wind. The Victorian era, however, witnessed the rapid development of steam technology which, when developed to the extent that it was able to replace equine power, offered new opportunities for travel. As with most new ventures, enticing commercial opportunities drove rapid advances in the application of steam, resulting in the railway boom of the 1840s and 1850s. Huge fortunes were anticipated by entrepreneurs keen to develop an integrated rail network across the land, and steam ships promised to extend the network (and the industrialists’ prosperity), still further.

Britain was the most technologically advanced nation in the world in Queen Victoria’s reign. Its engineering expertise was the catalyst for the growth of the new railway industry, supplying the machines and the infrastructure to meet the needs of this new form of travel both at home and abroad. Engineering works proliferated and this rampant industrialisation transformed several English towns such as Darlington, Crewe, Doncaster and Swindon, which henceforth became known as ‘railway towns’.

However, it was soon apparent that by the mid-nineteenth century, with the exception of a few commercial vehicles, steam was not suited to road transport. Many attempts were made to develop practical road vehicles for private travel, but the firing of the boiler, the provision of fuel and water, the dirt, the steam, and the sheer weight of the machines all conspired against their use. Furthermore, strict legislation limited the operation of these vehicles to the extent that further development for road use at that time was futile.

For the athletic and adventurous traveller, a new and exciting contrivance became fashionable in the 1870s; the high-wheel bicycle (subsequently known as the ‘penny-farthing’). Its use, however, was restricted to sporting young men since, by the very nature of its construction, it was impossible for ladies to ride owing to the fashions of the day. The high-wheeler, however, was not without its dangers, and due to the instability of the machine and the poor state of the roads at that time, falls from the much-elevated seat were frequent and considered even more hazardous than to tumble from the saddle of a horse. The solution was the ‘safety bicycle’, pioneered by John Starley in 1885. The device, which he named the ‘Rover’, utilised smaller, equally sized wheels that allowed for a far safer riding position. Easier steering and geared chain drive to the rear wheel also resulted in a faster, yet more stable machine. It was therefore inevitable that by the 1890s, to be seen pedalling a safety bicycle became the height of fashion.

The Morgans of Stoke Lacy

The industrial towns and cities where new forms of mechanised transport were evolving were far removed from the tranquil village setting of Stoke Lacy in Herefordshire. Presiding over the village was the vicar, prebendary George Morgan – a somewhat unlikely admirer of the railways, but a regular passenger for both ecclesiastical and recreational journeys. The Morgan family had made Stoke Lacy their home since 1871, when George’s father, the Reverend Henry Morgan, bought the living of the village and moved into the rectory. Henry enjoyed a comfortable living as, subsequently, did his son George, who inherited his father’s position and further enhanced the family’s prospects by marrying Florence Williams, who came from a very wealthy family in Kent.

The Morgans’ first child Henry Frederick Stanley (known in the family as ‘Harry’), was born on 11 August 1881. Three daughters followed: Frieda; Ethel; and Dorothy; another boy, Charles, sadly died in infancy. Being raised in such privileged circumstances, for Harry and his siblings life at the rectory in late Victorian times must have been very agreeable. George Morgan’s resources allowed the family to enjoy regular railway journeys to visit relatives in Kent, along with holiday excursions to a variety of seaside destinations. Given his father’s enthusiasm for rail travel, and the attraction of the steam locomotives, it was inevitable that young Harry Morgan became captivated by the bold designs and massive engineering of these machines.

Harry Morgan aged eleven in 1892, photographed by his father whilst at Stone House School in Kent.

By the age of ten, Harry was sent to Stone House, a boarding school in Ramsgate, close to his mother’s relatives in Kent. He was an average pupil, not particularly academic, but he showed a keen aptitude for the more practical subjects. With encouragement from his parents, who sent working model steam engines for Harry to play with at school, he was soon modifying and experimenting with these miniature machines in his leisure hours, discovering ways to improve their running. In this extra-curricular activity, Harry was joined by a fellow pupil, and was helped by one of the schoolmasters, who shared an interest in engineering and recognised the boy’s fascination for all things mechanical.

In May 1894, twelve-year-old Harry Morgan moved to Marlborough College in Wiltshire. George Morgan’s intention at that time was for Harry to progress to Eton, then to Cambridge and on to continue the family tradition as a clergyman. However, the ever-pragmatic Revd George soon realised that his son had little enthusiasm for an ecclesiastical vocation and accepted that a career in engineering was inevitable. For this, Marlborough College was certainly ill equipped! Harry soon began to struggle; he found the work difficult and uninspiring, and his academic results were poor.

The Morgan family vacation in August 1894 was, for Harry, the ideal antidote to his unhappiness at Marlborough. Making use of the railway network at home and throughout Europe, George took his family on a ‘Grand Tour’, across France, through the Alps to Switzerland and on to Geneva. From there they journeyed to Venice before returning home. George was a keen and very accomplished photographer and the images in surviving family albums record the many scenic locations encountered throughout their adventure.

Harry’s return to Marlborough would have been most disheartening; however, his father sought to mitigate the upset, and, responding to his son’s interest in mechanical contrivances, bought Harry a Triumph bicycle. Harry became the envy of his school friends, and the exasperation of his tutors. No longer confined to playing with models, he now possessed a real machine that he could maintain, develop and modify. Whenever the weather (and the school) permitted, the bicycle allowed him to explore the local district, covering many miles in the vicinity of Marlborough and the surrounding countryside. He even cycled back to Stoke Lacy on occasions. Harry spent four terms at Marlborough but became increasingly unhappy there, his health suffered due to the poor diet (he was never a particularly strong boy) and he finally left in July 1895.

The Pursuit of Engineering

Little is known of Morgan’s subsequent schooling from surviving records, but it is likely that he was privately tutored at Stoke Lacy. By the late 1890s, Morgan was determined to pursue a career in engineering as he witnessed the first examples of rudimentary motor cars taking to the highways. Impractical, unreliable and crude, these machines were rare; the playthings of adventurous and wealthy folk. Morgan, however, could see their potential and anticipated the day when they would replace private horse-drawn conveyances, much as the railways had done for long-distance travel.

Harry next spent a brief period at a private school in Clifton, Bristol, arriving in the autumn of 1898. Bristol was a city with strong connections to engineering, especially railways and steam ships, and in particular, the work of the most famous engineer of the Victorian era; Isambard Kingdom Brunel. It is evident that Morgan was most satisfied with this placement, as letters home to his parents testify. Harry’s bicycle remained his primary means of travel and its maintenance and development occupied much of his leisure time.

In the summer of 1898 whilst at home in Stoke Lacy, Harry became acquainted with Leslie Bacon, a boy from the nearby town of Bromyard. Harry and Leslie were the same age to within a few weeks, and shared a passion for engineering. They spent long hours with Harry’s bicycle and any other mechanical objects to hand, becoming familiar with the intricacies of these devices. Some years later the boys would become business partners, but in 1898 their immediate priority was to gain entry to a suitable establishment that could provide the necessary training to become professional engineers.

One of the most prestigious engineering colleges of the day was at the Crystal Palace in Sydenham, London. Having first applied in July 1898, it was here that, in September 1899, George managed to secure a place for his son. The engineering school occupied four floors of the south tower; a prominent feature of the spectacular Crystal Palace, Joseph Paxton’s magnificent cast-iron and glass structure originally built for the Great Exhibition of 1851. Here, Morgan studied the fundamentals of engineering, spending periods in the drawing office, pattern shop, machine and fitting shop, electrical section and civil engineering department.

The work involved basic engineering practices and associated arithmetic and drawing skills, but it was on the drawing board that Morgan became particularly proficient. He studied both civil and mechanical engineering, but it was the latter that fascinated him most. He learned basic workshop practices and built his own engine, skills that would prove most beneficial in years to come. In his leisure hours Harry continued to develop his bicycle and often competed at the Palace’s own velodrome, around which he became virtually unbeatable in bicycle races. However, another extra-curricular event made a particular impression on the young would-be engineer. Whilst at the Crystal Palace in the spring of 1900, he witnessed the Automobile Club’s 1,000-mile trial, providing ample opportunity to closely examine a variety of the finest early automobiles.

At the dawn of motoring there were no conventions, no standard configurations; the only guidance for designers and engineers came from experience gained in the construction of horse-drawn vehicles. Indeed, many early motor cars were little more than equine carriages in which the horse was replaced by some form of engine. Opinions differed concerning the best type of energy to employ. Steam was an established technology; now a more practical proposition for automobiles since the French engineer Léon Serpollet had developed the ‘flash tube’ steam boiler in 1886. Rapidly gaining popularity was the four-stroke internal combustion petroleum engine patented by German engineer Nikolaus Otto in 1877, which was considered a cleaner, more convenient form of propulsion. Adding to the power options was the electric motor, first employed by French inventor Gustave Trouvé, who had tested his three-wheeled machine along a Paris street in 1880. However, the primitive lead-acid battery had limited power, so the motor could only manage a modest top speed and the vehicle’s range was very limited. All three alternatives had their advocates amongst the pioneering motor manufacturers, but only time would tell which one would endure to dominate the industry.

In Victorian Britain, a few visionary engineers were experimenting with primitive self-propelling vehicles; however, the most significant developments were being made in Germany. Karl Benz in Mannheim is generally regarded as creating the first practical automobile in 1886, named the Benz Motorwagen. Meanwhile, in 1889, Gottlieb Daimler built his Stahlradwagen (or ‘steel-wheeled car’) in Bad Cannstadtt, a suburb of Stuttgart. Development of the motor car continued mostly in Germany, although it was the French who subsequently took the lead and started producing vehicles in considerable numbers; DeDion Bouton, Renault and Panhard et Levassor being the major players at the turn of the century.

Morgan applied his engineering training and inventive mind to assess both the benefits and shortcomings of the machines he had witnessed on display at the Crystal Palace. He studied publications such as the Autocar, launched in 1895 – the first motoring magazine to appear on news stands. He collected photographs and magazine cuttings in a scrapbook and was able to objectively compare the disparate mechanical arrangements of a wide variety of machines. It occurred to Morgan that success relied upon the ingenuity of the manufacturers to devise a vehicle that was reliable, affordable and easy to operate – not attributes that could be taken for granted at that time.

The adoption of the motor car in Britain had been slow compared to continental Europe, as the repressive laws governing their use severely limited the popularity of the automobile at home. The old ‘Highways and Locomotives Act’ – popularly known as the ‘Red Flag’ Act – had eventually been rescinded in November 1896, but this left British motor manufacturers trailing behind those of France and Germany. The repeal of the law had, at least, given a new freedom to British motorists, although many drivers transgressed the still-stringent limits placed upon road users and were dealt with harshly by the courts. Any form of motorsport or competitive driving was likewise strictly discouraged. The development of Britain’s motor industry therefore remained seriously behind that of other European countries. For Harry Morgan, who was approaching the conclusion of his schooling, the design and development of automobiles offered a new and enticing career path. First, however, he needed to augment his mostly academic knowledge with practical experience in an appropriate engineering establishment.

In 1901, Revd George Morgan again used his influence to secure a premium apprenticeship for his son at the factory and maintenance depot of the Great Western Railway in Swindon. A position in railway engineering might appear somewhat inappropriate considering Harry’s passion for motor cars; however, at the turn of the century motors were still in their infancy, therefore the most advanced and innovative engineering was to be found with the comparatively long-established railway industry. Morgan’s apprenticeship was overseen by two of the finest railway engineers of the time – William Dean, chief locomotive and wagon superintendent of the GWR, and Dean’s successor, George Jackson Churchward.

Morgan spent time in the vast workshops at the Swindon plant, gaining first-hand experience of casting and machining components, the assembly and testing of complex mechanisms, and the overhaul and repair of older engines. But of all the new disciplines he was taught, he displayed the greatest aptitude for engineering drawing. In the GWR drawing offices he witnessed the design and development of new ideas – innovations at the very forefront of engineering expertise of the day.

Prebendary George Morgan was one of the first motorists in Herefordshire, having acquired his Lanchester in 1902. He is seen here outside Stoke Lacy Rectory with his wife Florence and daughters Freida, Dorothy and Ethel.

Whilst Queen Victoria’s reign had seen the rapid development of steam technology, the Edwardian era marked the beginning of the dominance of the internal combustion engine. In 1902 the Morgans, both father and son, became motorists. Revd George Morgan bought a Lanchester, a large, rather sedate tiller-steered automobile as would befit a respected clergyman. George thus became one of the first motorists in Herefordshire. Registered CJ22, George Morgan’s car was a handsome machine, featuring a tonneau body painted green and lined in red. Dressed in the most fashionable motoring outfits of the period, the Reverend George and Mrs Morgan, frequently with the children in the capacious rear, were a familiar sight around the local country lanes.

In contrast to his father’s dignified conveyance, Harry was given an Eagle Tandem for his twenty-first birthday – a three-wheeler of a type known as a fore-car, which had a single driving seat mounted high above the rear wheel and an elaborate buttoned-leather seat for the passenger in front. The Eagle was fast but not too reliable, and gave Harry some interesting experiences during the eighteen months that he owned it.

Harry Morgan on his Eagle Tandem outside Stoke lacy Rectory.

In June 1904, shortly before finishing his apprenticeship at Swindon, Harry sold his Eagle and the following month replaced it with a 7HP, 2-cylinder Little Star, registered FK62. This was a conventional four-wheeled motor car, built in Wolverhampton, fitted with a two-seater body and painted deep red. The Little Star served Harry well for a few years and was his main means of transport as he completed his apprenticeship and embarked on a career in automotive engineering.

Having completed his apprenticeship, in 1904 Morgan spent a brief period working in Swindon’s GWR drawing office.

Harry now turned his attention to finding a position which would further his interest in automobiles. The GWR had a motor car department at Paddington station, but regrettably there were no vacancies at that time. George Morgan had also been busy on his son’s behalf and in December 1904, using his influence as a Lanchester customer, contacted Mr Frank Lanchester to enquire about a position with the firm. The Lanchester works were in Montgomery Street, Birmingham, not too far from Stoke Lacy. Lanchester replied, offering Harry, ‘the opportunity of gaining experience of our cars at the commencement of next season.’

The offer must have been tempting, since the company was renowned for its radical and innovative engineering, not only as applied to automobiles, but in the latest mechanical discipline of aeronautics. However, after careful consideration Harry decided not to accept Lanchester’s offer, as he had ideas of his own as to his future career.

Morgan & Co., Garage and Motor Works

Throughout the winter of 1904/5, Harry Morgan had ample opportunity to discuss various vocational options with his father. Whilst employment with a major motor company was the obvious way forward, the opportunity to establish his own business was an enticing notion. His friend Leslie Bacon was likewise searching for employment, having recently completed his railway engineering apprenticeship at Darlington. Regular get-togethers at the rectory during Christmas and New Year would have given the two friends ample time to make plans for the future. Before long the decision had been made: Harry would set up in business, opening a motor car garage and securing the local agency rights for a variety of motor manufacturers.

In the early months of 1905, with the full support and financial backing of his ever-enthusiastic father, Harry Morgan acquired a plot of land which included a house called Chestnut Villa, in Worcester Road, Malvern Link, and built a small garage on the site. The choice of location was an inspired move, since the beautiful Malvern Hills and the benefits of the many hydropathic health spas in the town attracted wealthy visitors – just the sort of people who could afford to indulge in the new and exciting adventure of motoring. Joining Morgan in this venture was his close friend Leslie Bacon, who also became Harry’s tenant in Chestnut Villa. The scene was now set for the emergence of one of the most extraordinary stories in the history of the British motor industry.

Morgan’s new garage opened on 20 May 1905. He had negotiated the sole rights in the district to sell Darracq, Wolseley and Siddeley motor cars. Wealthy visitors driving their own automobiles on ‘motor tours’ – a very fashionable pastime in the Edwardian period – would stop at the Morgan Garage for supplies of petroleum spirit or to seek help with maintenance or repairs to their vehicles.

Very few people could afford a new car at that time, so Morgan also offered a selection of second-hand cars for sale. Hire cars (complete with driver) were also available from the garage, charged per day (£3 3s.), or per week (£15 15s.), or by distance (1s. per mile, minimum charge 3s.).

Realising the need for better transport facilities for local people, Morgan introduced a Public Service Car (using a large 22HP Daimler motor car), which was to run from Malvern Link, along Worcester Road; the main thoroughfare through the town, via the Belle View Hotel in Great Malvern, and continue to Malvern Wells. This embryonic facility would soon develop into Malvern’s first bus service.

Morgan and Co. Garage and Motor Works, May 1905. Vehicles from left to right are: 22hp Daimler AB436, 6hp Wolseley, 12hp Lanchester with Brougham top P1207 (with Harry at the wheel), 7hp Little Star FK62, 12hp Lanchester Tonneau five-seater.

Morgan’s new enterprise, however, was not without its detractors. The presence of his garage and the gradual increase in motorised traffic in the locality caused many residents to raise complaints in the press and with the local council. Their grievances included the danger posed to women and children by reckless and inconsiderate automobilists who, frightening horses and other wildlife, polluted the air with fumes, dropped oil on the highway, damaged roads in the town due to the weight of the vehicles, and in consequence, raised clouds of dust from the wheels and ‘blowpipe exhausts’. Needless to say, Harry Morgan’s business became the target for much criticism, and his establishment was far from popular with many local people.

Despite criticism from certain quarters, Morgan’s Garage proved to be a very popular amenity and the business thrived. Such was the unreliability of early automobiles that the presence of a well-equipped ‘motor works’ in the district often dictated the route taken through the Worcestershire countryside. Furthermore, for the adventurous motorist, the Malvern Hills provided a tough, but rewarding challenge to the hill-climbing capabilities of primitive automobiles. These were expensive machines and their wealthy occupants, on visiting Malvern, would naturally demand the very best when patronising hotels and restaurants in the town. Malvern therefore gained a reputation as one of the most fashionable destinations for the rich and famous.

For the less-affluent traveller, the only option for personal motorised transport was the emergence of the first motorcycles. Matchless was one of the first companies in Britain to introduce motorcycles, developing a machine in 1899 and eventually going into production in 1901. Another motorcycle pioneer was John Alfred Prestwich, who built his first machine in 1902, known as a ‘J.A.P’. Some years later, both J.A.P. and Matchless would play a major role in the development of the Morgan three-wheeler.

Early motorcycles slowly gained acceptance with adventurous, sporting young men, but being solo machines, they failed to appeal to couples or families. Some attempt was made to accommodate a passenger with the adoption of the sidecar, but even so, few ladies chose to ride in such a primitive contraption. Although the technology was improving, the motorcycle at that time remained a rather impractical means of transport.

Motoring for the Common Man

The concept of combining the simple mechanical arrangements of early motorcycles with a lightweight three- or four-wheeled chassis had occupied the thoughts of many engineers at the turn of the century. France was foremost in this field of experimentation and a few of the more capable engineering firms, such as Leon Bollé and DeDion Bouton, achieved success with their designs and went into production. In France these were known as ‘voiturettes’, better known in Britain as ‘fore cars’ on account of the seating position for the passenger – rather perilously exposed at the very front of the machine! Harry Morgan’s Eagle Tandem shared the layout of a fore car, but here the similarity ended, the Eagle being a relatively large, heavy (and expensive) vehicle.

Whilst Morgan’s garage business was going from strength to strength, his true passion was for engineering design and innovation. The motor car may have been gaining in popularity, but it was still strictly in the domain of the wealthy. Morgan perceived that there was potentially a huge market for a smaller, simplified automobile, a machine that would replace the primitive fore car, and would provide more comfortable and practical transport than the motorcycle and sidecar.

Morgan’s youthful experimentation with bicycles, his engineering training both theoretical and practical, plus his subsequent involvement with automobiles, allowed him to assess the benefits of the various mechanical arrangements currently available from different manufacturers. Many vehicles were over-engineered but underpowered, fitted with unnecessarily heavy bodies, luxurious upholstery and elaborate fittings. He surmised that it was feasible to construct a simple, lightweight machine, requiring just a modest-sized engine, and fitted with a minimal body devoid of excess embellishments, that would also deliver a good performance. Such a machine would be comparatively easy to build and inexpensive, enabling its maker to exploit a hitherto untapped market, aimed at the lower-to-middle income family. This would be a vehicle for the average man (and occasionally woman) who would otherwise never be able to afford a conventional automobile.

Morgan was not alone in this venture and was aware that other designers and engineers were developing minimal machines designed to fill the gap between motorcycles and conventional motor cars. Most of these were ill-considered contraptions that failed to perform even at the developmental stage, let alone managed to reach production. A new expression, ‘cyclecar’, was devised, and many an optimistic constructor believed that they could exploit this emerging market. Not all of these businessmen were engineers, and the deficiencies of their designs were soon apparent.

Morgan however, was a trained engineer and applied his knowledge methodically to begin work on a machine that would combine strength and lightness; as he explained a few years later:

‘In 1909 I designed a motor bicycle, but before it was completed, I succumbed to the fascinations of the cyclecar. Although I had been a very keen cyclist, I never cared for motorcycles.’

1909 – The Morgan Prototype

Morgan’s cyclecar project was regarded with some suspicion by his business partner Leslie Bacon, who considered that it could potentially compromise an otherwise successful car agency business. There is no evidence to suggest that Bacon was involved in the design or construction of the vehicle. The main challenge facing Morgan was the more practical problem of accessing the necessary engineering facilities to begin construction. The Worcester Road garage had a small workshop with basic machine tools, but fell short of the requisite amenities to build the complete machine. To help with the project, Harry’s motoring friends, brothers George and Robert Stephenson-Peach, introduced him to their father, Mr William Stephenson-Peach, engineering Master at Malvern College, and a pioneer of practical engineering in schools and colleges during the Edwardian period.

Morgan’s prototype cyclecar outside the Malvern College workshops. This is the earliest known image of a Morgan car, taken in the spring of 1910 when the machine was on test in the College grounds. The identity of the driver is alas, unknown.

Stephenson-Peach had previously experimented with, and built, several motorcycles, three-wheelers, and four-wheeled motor cars in engineering workshops at his former home near Repton in Derbyshire. Here, in addition to his commercial engineering work, he also taught pupils from Repton School, who were offered engineering tuition on the curriculum, Repton being one of the first schools in the country to do so. Assessing Morgan’s design, Mr Stephenson-Peach agreed to not only make the college workshops available to Harry, but to help and advise him with the project.

Throughout 1909, when garage commitments permitted, Morgan worked with William Stephenson-Peach to refine his design and construct the machine in the college workshops. Drawing on his experiences with bicycles, Morgan recognised the benefits of a simple tubular steel frame and therefore used this method to form the basic structure of his new chassis. The main ‘backbone’ was a two-inch tube aligned with the engine crankshaft and thus the axis of the transmission. This tube was bolted, via a brazed flange, to a fabricated steel gearbox, if it could be called such, since all it contained was a simple pair of bevel gears. Pivoted at the rear of this box was a set of forks supporting the single rear wheel. At the front of the vehicle, further tubes were set transversely across the main frame and at their extremities, carried the steering and suspension mechanism for the two front wheels. The chassis was braced by two further tubes from the bottom of the cross-head, to fittings under the gearbox, thus achieving a triangulated arrangement. These tubes also supported the floorboards. Considering the materials available at that time, it would be difficult to imagine a lighter, more minimal structure whilst achieving the necessary degree of strength and rigidity.

To power his machine, Morgan used a Peugeot 7HP, 45-degree, V-twin engine. Peugeot, in France, was a well-established motor car manufacturer, who, in 1901, had diversified to produce motorcycles, and by 1905 introduced a range of V-twin engines. Morgan set the engine transversely across the front of the frame where it gained the greatest benefit from the rush of cooling air. Transmission was via a conventional metal-to-metal cone clutch within the external flywheel, to a prop shaft that drove a pair of bevels within the gearbox. The crown wheel was mounted on a cross shaft, on which the driving sprockets freely rotated. These were keyed to the shaft by a simple sliding dog clutch arrangement that selected either the high or low ratio set of sprockets and chains to drive the rear wheel. There was no reverse gear. Brakes were fitted either side of the rear wheel only and were the conventional externally contracting band type; one was operated by a foot pedal and the other from a hand lever. Steering was by tiller, a method favoured by some pioneers around the turn of the century, but a rather odd choice a decade later.

Completed towards the end of 1909, Morgan’s cyclecar was tested on roads within the Malvern College grounds. Tests showed Morgan’s prototype to perform well, the lightweight Peugeot V-twin engine being more than capable of propelling the machine at an impressive pace.

Mr Chris Booth drives his replica of the 1909 prototype along roads within the Malvern College grounds during Morgan’s 100th anniversary celebrations in 2009. The original vehicle had used the very same roads for testing a century earlier.

Having proved the concept, Morgan now considered his next move. Several observers had remarked upon the impressive performance of the machine and suggested that he build further examples to sell from his garage. This clearly raised further concerns for Leslie Bacon; however, Morgan could see the potential of his machine and decided to test the market by exhibiting an improved example at the ‘International Cycle and Motor Cycle Exhibition’, due to be held at Olympia in London in November 1910.

With William Stephenson-Peach’s help, Morgan identified a few areas where improvements could be achieved and plans were made to build an additional three chassis to exhibit at Olympia. Since this would cause far too much disruption in the Malvern College workshops, Stephenson-Peach offered Morgan the use of more extensive facilities at Repton, where he maintained his commercial engineering interests. In the early months of 1910, Morgan and Stephenson-Peach visited Repton and worked on the project with workshop foreman Frederick Smith. Modifications to the design were considered, and Frederick Smith documented these changes, producing two engineering drawings. These historic drawings, rediscovered a few years ago by the author, are the oldest surviving representations of the first Morgan Runabout and provide a fascinating technical record of the machine. Dated 9 March 1910, they show a halfway stage between the prototype and the Olympia Show cars, as refinements were made.

Morgan’s ‘Runabout’, a section of a drawing by Frederick Smith, dated 9 March 1910. It shows the forward section of the tubular steel chassis forming the engine mounts, plus the cone clutch arrangement.

As work progressed at Repton, improvements were tested on the prototype in Malvern. The fuel tank was enlarged, simple front wings were added to prevent mud being flung towards the driver, and an acetylene light was added for nighttime driving. In June 1910, Morgan registered the vehicle with the Herefordshire authorities, being allocated the number CJ743. Finally, to improve the comfort and the aesthetic appeal of the machine, a new body was made and fitted by Pettifer’s garage in Bromyard. Albert Pettifer was well known to the Morgan family and maintained Revd George Morgan’s motor cars.

Experimentation with the prototype and further innovations resulted in the Olympia show cars differing somewhat from the original design. The gearbox was now a bronze casting into which the main chassis tube was soldered. The tubes supporting the floorboards were now moved inwards to run parallel to, and set below, the main tube. Intent on using the minimum possible number of elements, Morgan arranged that these two lower tubes now doubled as exhaust pipes.

Although the prototype used a Peugeot engine, Morgan considered that a British-built engine would be preferable. The simplicity of his design meant that almost any V-twin, or single cylinder engine could be fitted, the only modification required being a different set of engine-mounting plates. For the three Olympia cars Morgan chose J.A.P. engines; two 8HP V-twins, and one 4HP single.

A section of the second drawing by Frederick Smith, dating from the summer of 1910, showing the bevel box and transmission arrangement. The prop-shaft (entering the bevel box far right), drives via a set of bevel gears, the cross-shaft, and thence, via chains and sprockets, to the rear wheel (seen on the left).

Throughout the summer of 1910, Frederick Smith and his staff at Repton assembled three new chassis. The bronze gearbox (otherwise known as the bevel-box) was cast in the Repton workshops; other castings came from local engineering firms. The tubular steel frames were brazed together at Repton and, when completed, the chassis were transported to Malvern for finishing and final testing. For the Olympia Show, Morgan decided to display one of the V-twin chassis without bodywork so that the clever mechanical layout could be observed. The other two chassis were fitted with bodies built by Albert Pettifer in Bromyard, the 4hp having a simple seat and floorboards, the 8HP featuring a slightly more enclosed body with leg protection, very much the same as the prototype in its final form. The machines were finished in a light grey paint scheme, with black coach-lines around the panel edges.

Having proved his design, Morgan now sought to protect some of the machine’s innovative features from being plagiarised, and on 8 September applied for a patent for ‘Improvements in the Design and Construction of Tri-Cars or other Light Automobile Vehicles’. Patent No 20,986 was finally granted on 17 August 1911.

Morgan’s Peugeot-engined prototype in its final form, photographed in the grounds of Stoke Lacy Rectory in the summer of 1910.

Morgan named his new cyclecar the ‘Runabout’ and a local printer produced a simple brochure describing the Runabout thus:

‘The “MORGAN RUNABOUT” is a single-seated car, designed by a practical motorist to combine the comfort and safety of a motor car with the cheapness and simplicity of a motor cycle.

The “MORGAN RUNABOUT” is not a toy. It has been severely tested. It is fast and will climb any hill. It never becomes overheated. It is comfortable; a good rug and coat can be used by the Driver. It is thoroughly well sprung. Above all it is safe. The safety of the “MORGAN RUNABOUT” is secured by the very low centre of gravity, and the special method of springing, which makes an overturn impossible. Doctors will find the “MORGAN RUNABOUT” invaluable in their practice, even if they possess other cars; so also, will Commercial Travellers, as the “RUNABOUT” is designed to carry a very considerable amount of luggage.’

Olympia – Morgan’s Runabout is Revealed to the Public

‘The International Cycle and Motor Cycle Exhibition’ opened at Olympia in London on Monday 21 November 1910, the first exhibition of its kind in Britain. Morgan displayed his three machines on stand No. 250 in the Annexe. The struggle for recognition was fierce, there being numerous rivals, all vying for the public’s attention. The name H.F.S. Morgan was unknown; just one young engineer amongst many, trying to make his way in the fledgling motor industry. However, those observers with some knowledge of engineering could clearly see the superiority of Morgan’s design. Throughout the show the public response to the Morgan Runabout was very positive and many favourable comments were received. Journalists from the various motorcycling magazines were likewise impressed and reported on the Runabout with enthusiasm. Despite these encouraging endorsements, the number of orders received was disappointing, reports suggesting that fewer than twenty people had committed to buying a Morgan. The principal reason was the absence of accommodation for a passenger; all the display chassis being solo machines.

Harry Morgan’s youngest sister Dorothy in an early production 8HP ‘Runabout’, photographed in the grounds of Stoke Lacy Rectory, probably in the spring of 1911.

Morgan’s youngest sister Dorothy recalled that as far as Harry was concerned ‘The show was an absolute flop’. The solution however, was relatively straightforward, with a little ingenuity and some modifications, the Runabout chassis could easily be adapted to seat two persons. The fundamental question though, was would the machine sell in sufficient numbers to make the enterprise viable? If so, how could Morgan achieve the levels of production necessary given the limited facilities of his small garage? Diversifying a successful business in order to build motor cars was a huge gamble and had been the downfall of many an entrepreneur. Morgan had his garage, his dealerships, his private hire car and public omnibus services in the town; was he willing to risk all of this in the pursuit of his Runabout?

The author driving his recreation of Morgan’s first production 8HP ‘Runabout’ of 1910, photographed at Stoke Lacy Rectory.

A rather unlikely factor that may have ultimately influenced Morgan’s decision was the patronage of Richard Burbidge, managing director of Harrods in London. Having met with Morgan at the Olympia Show, Burbidge was impressed with the Runabout and offered to display the machine in his department store in Knightsbridge and promised some sales. Morgan now had to deliver the goods. To address the problem of production capacity, he approached a number of established motor manufacturers to determine if they were interested in buying the rights to his design, or perhaps entering into a partnership to build the machine. In this he was unsuccessful. If the Runabout was to succeed, Morgan had to build it himself.

Putting the ‘Runabout’ into Production

The Olympia Show had convinced Morgan that the ‘Runabout’ was a viable project. The garage business and dealerships were to be discontinued, the motor omnibus service would cease, and the workshops re-organised and extended for car production. Financial support (and moral support) for the new venture came from the ever-enthusiastic Revd George Morgan. ‘Morgan & Co. Motor Engineers’ were now car manufacturers. For Harry’s business partner Leslie Bacon, these latest developments were far too risky, and so he quit the partnership.

The first priority was to build the cars ordered at Olympia. Whilst William Stephenson-Peach had been invaluable with the development of the Runabout, it was obvious that he was in no position to help with quantity production. Morgan therefore equipped his Worcester Road workshop with extra machinery and engaged additional staff. He also approached fellow Malvern Link motor engineer Charles Santler, to whom he sub-contracted some of the machining work. The bronze bevel box and other castings came from one of the many foundries in Birmingham. These were brazed and soldered to a framework of steel tubes in Morgan’s workshops, to form the chassis.

Engines were supplied by J.A.P., and fitted with Brown and Barlow carburettors and Bosch magnetos. The British Hub Co. supplied the wheels, which were then fitted with Dunlop tyres. Bodies were built by Albert Pettifer in Bromyard and transported to Malvern Link in Pettifer’s post van (Pettifer had a contract to deliver post in the Bromyard district). The bodies were coach-painted in a standard light grey finish in Morgan’s workshop before being mated to the chassis. Accessories, if ordered, were the final parts to be added, such as a Lucas horn, or an acetylene lighting set from the Birmingham firm of Powell & Hamner. Finished Runabouts were tested on the local roads prior to despatch. Machines would usually be sent to their final destination on the railway network, Malvern Link station being conveniently situated adjacent to Morgan’s works, although some customers collected their vehicles directly from the factory.

Harry Morgan drives the modified ‘Runabout’ in the MCC London to Edinburgh Trial of April 1911.

With Runabout production now well established, the Olympia Show orders were completed, and work continued to fulfil subsequent orders from Harrods, although demand at this time was quite modest. To further promote his Runabout, Morgan decided to embark on a series of reliability trials, designed to test the strength and practicality of machines. Since it was intended that the new Morgan should compete directly with motorcycles, the Runabout was entered for the Motor Cycling Club’s (MCC) London to Exeter Winter Trial, scheduled for 26/27 December. This was a severe ordeal for both driver and machine, especially considering the poor state of the roads at this time, but the Runabout ran remarkably well and Harry won a Gold medal for his performance.

More success followed on the MCC London to Edinburgh Trial of April 1911. Minor changes had been made to the Runabout for this event, the most noticeable being a torpedo-shaped fuel tank. Despite sustaining damage when the machine hit a wall, Morgan finished the event and was awarded a special gold medal.

Developing a ‘Sociable’ Two-seater

Morgan’s next priority was to address the issues that had compromised sales at Olympia, in particular the lack of a two-seater and the rather antiquated tiller steering. In the early months of 1911, a crude two-seater body was fitted to an otherwise standard chassis (still steered with a tiller), to assess the performance of the car with two adults on board. Experiments proved successful and soon a production two-seater was under development, steered with a steering wheel. Customers could now choose the ‘sociable’ two-seat Runabout, or the monocar with revised bodywork. The aesthetics of the Runabout had evolved into a more refined machine with marginally better weather protection for the occupants, but other than the steering, the mechanical arrangements remained virtually the same.

The new two-seater ‘Morgan Runabout’, now with wheel steering, photographed outside the factory in Worcester Road, Malvern Link.

A surviving workman’s time book from February 1911 shows that Morgan employed a staff of eight local craftsmen at that time, most of whom lived nearby in Malvern Link. Work was overseen by Alfie Hales, a brusque, rather autocratic character from Birmingham, who had joined Morgan as garage foreman in 1906. Hales lived with his family close to the factory at No. 32 Redland Road. Working hours were from ‘8 in the morning till 7 at night, Monday till Friday, and 8am in the morning till 1pm on Saturdays’. Mr R. Baker was Alfie Hales’ second in command, being paid thirty-two shillings per week, considerably more than other workers!

The prototype two-seater made its competition debut in the Auto Cycle Union’s (ACU) Six Days Trial in August 1911 and, although performing well, success eluded Harry when the prop-shaft failed. This, however, vindicated Morgan’s decision to subject his machine to the extreme conditions of trials driving, which highlighted any potential weaknesses in his design and allowed him to make improvements to production Runabouts.

Morgan’s two-seater ‘Runabout’, now with wheel steering and weather protection, photographed on the stand at the 1911 Olympia Motor Cycle Show.

The two-seater went into production in September 1911 and, anticipating a great demand, Morgan made preparations to display his three-wheelers at the Olympia Motor Cycle Show in November. The new car, he felt sure, would attract many new customers, offering comfortable seating for two and providing a degree of weather protection with the option of a hood. The latest V-twin engine from J.A.P. gave a lively performance and for the solo motorist the monocar now sported a very rakish new body.

The Olympia Show opened on the 18 November and from the very start business was brisk. Following a very complimentary report in Motor Cycling magazine by journalist W.G. McMinnies, word had spread amongst enthusiasts about the exciting new Runabout, making it one of the ‘must see’ exhibits at the show. At 85 guineas (£7 extra for a windscreen and hood), the Runabout compared most favourably with the more powerful motorcycle and sidecar outfits. Dozens of orders were received, easily outstripping Morgan’s production capacity at his Worcester Road factory. Success however, raised new concerns about the Company’s ability to fulfil the orders – customers would have to be put on a waiting list, and that list was growing rapidly!

The Harrods Connection

A solution to the problem of large-scale production came from Richard Burbidge of Harrods department store, who had helped Morgan to promote the Runabout the previous year. Burbidge placed an immediate order for fifty machines and paid a deposit of £500 on the understanding that Harrods would be the sole concessionary for the Runabout. Furthermore, Harrods would arrange for bodies to be made and fitted, leaving Morgan to concentrate on just the chassis, thus easing the situation at the Malvern factory.

The 1912 Harrods-bodied ‘Runabout’. The substantial body proved to be too heavy and in consequence, the car’s performance suffered.

Soon after the close of the show, Harrods sent letters to no fewer than four hundred and twenty-six potential customers who had enquired about the Runabout, this at a time when the factory had recently increased its output to just seven cars per week! Even with Harrod’s backing, meeting this potential demand was a daunting task. By January 1912 Harrods ordered a further fifty cars and paid a deposit of £520. Delivery of the Harrods-bodied cars was scheduled to begin in March 1912.

At first the Harrods association appeared to work well. A London coach building firm produced the bodies and, although these appeared to be well-built and comfortably upholstered, they were significantly heavier than those made by Albert Pettifer and fitted by Morgan. This went against Morgan’s philosophy of simplicity and minimum weight. The performance of the Harrods cars consequently suffered and Morgan became increasingly concerned that the Runabout’s reputation would be compromised.

The deal with Harrods soon ran into trouble when in February the delivery of chassis fell short by four cars, cars for which Harrods had customers waiting. Burbidge sent a strongly worded letter to Morgan, pointing out the error and insisting that the shortfall be rectified. It would appear that rather than ‘putting all his eggs in one basket’, Harry Morgan was also despatching cars to other dealers, namely Jack Sylvester in Nottingham, and Billy James in Sheffield, apparently in contravention of the agreement with Richard Burbidge. It is not known how many Harrods Runabouts were built, or when the contract with Harrods was rescinded, but a few months later Morgan was free of the arrangement and set about the task of establishing his own network of agents. Morgan must have come to an amicable agreement with Burbidge, since Harrods continued to advertise and supply Morgan Runabouts to their customers for some years thereafter.

The Morgan Motor Company Limited

Morgan now faced the considerable challenge of meeting the demand for the Runabout from his own resources. To achieve the extra capacity, the Worcester Road works were enlarged with further extensions to the rear of the original garage, plus additional wooden buildings extending back towards Redland Road. To reflect the expansion and progression of the business, a new company was formed. On 1 April 1912, ‘Morgan & Co.’ became ‘The Morgan Motor Company Limited’. Harry Morgan was managing director, his father George, who had provided much of the finance for the venture, was chairman. The two men were the only shareholders.

Chassis production in the Worcester Road factory, 1912. Harry Morgan (wearing cap) is seen standing slightly left of centre, with workshop foreman Alfie Hales to his left.

Driving chassis production to ever-greater numbers was the formidable presence of works foreman Alfie Hales, who tolerated no slacking and pushed the men hard. It was said that even Harry Morgan, ‘The Boss’, was somewhat wary of his foreman!