6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

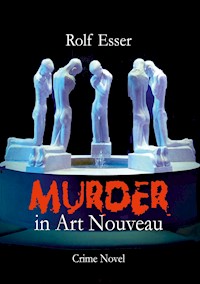

Why are the director of the Hagen Osthaus Museum and his deputy murdered? Why is a well-known art forger reactivated? On which wise disappeared valuable paintings from the museum during the Nazi era? And what has the Naples Camorra to do with all this? Questions upon questions that lead to a real confusion. In any case, the murders are causing excitement in Hagen. The police is initially faced with a mystery. Can this complicated case be solved?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 309

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Murder in Art Nouveau

Rolf Esser

Imprint

Author: Rolf Esser © 2022

Cover design, layout: Rolf Esser © 2022

ISBN Softcover: 978-3-347-75471-3

ISBN Hardcover: 978-3-347-75472-0

ISBN E-Book: 978-3-347-75473-7

Publication and distribution are on behalf of the author:

tredition GmbH, Halenreie 40-44, 22359 Hamburg, Germany.

This work, including its parts, is protected by copyright. Any exploitation is prohibited without the consent of the publisher and the author. This applies in particular to electronic or other reproduction, translation, distribution and making available to the public.

The translation of this book was done with Deepl translator. There may be some mistakes and misunderstandings. Nevertheless, the reader should be able to see what is meant.

Cover motif: Boy's Fountain by George Minne in the fountain hall of the Osthaus Museum Hagen, copy by Paul Kußmann 1974; with kind permission of the Osthaus Museum Hagen.

Rolf Esser

Murder in Art Nouveau

Crime Novel

Content

Characters of the Plot

Chapter 1 - Death in Style

Chapter 2 - Shadow Worlds

Chapter 3 - Investigative Work

Chapter 4 - Machinations

Chapter 5 - Implications

Chapter 6 - Revenge, Blackmail, Murder

Chapter 7 - Search for Clues

Chapter 8 - Deadly Decisions

Chapter 9 - The Noose Tightens

Chapter 10 - Final Reckoning

Books by Rolf Esser

Characters of the plot

Museum & Art

- Ricardo Sommer - Museum Director

- Dr. Karin Schmitt alias Sigrid Ahlers - Deputy Museum Director

- Rudi Schmalsteg - employee in the museum workshop

- Annette Schneider - Museum Treasurer

- Hofmann, Dieter - Museum Technician

- Gerhard Brüns - Museum Director from 1934

- Heinrich Pfingsten - Museum Curator 1937

- Elisabeth Korn - daughter of Heinrich Pfingsten

- Gerhard Koch - Museum Caretaker 1937

- Peter Koch - son of Gerhard Koch

- SS-Standartenführer Fröhlich - Reporter 1937

- Helmfried Gründlich - art dealer 1937

- Friedemann Gründlich - son of Helmfried Gründlich

- Helmut Vinzenz - art forger

- Ingrid Vinzenz - wife of the art forger

Crime Squad

- Günter Etsch - Chief Detective Inspector

- Katharina Weil - Detective Superintendent

- Timo Weil - son of Katharina Weil

- Else - mother of Katharina Weil

- Eberhard Kunzner - Drug investigator

- Ralf Kanter - BKA

- Mrs Siebert - secretary to the Hagen Police Chief

- Harald Misch - Duisburg narcotics officer

- Herbert Rein - Public Prosecutor

- Renate Unger - Detective Superintendent

Underground

- Gerald Meissner - art pusher

- Manuela Hess - girlfriend of Gerald Meissner

- Andreas Stamm - the burly one

- Ralf Kusch - the gaunt one

- Edwin Schulte - 1st dark man

- Gregor Sanders - 2nd dark man

- Pinter - 3rd dark man

- Giuseppe Moretti - Mafioso

- Salvatore Detto - Mafioso, companion of Moretti

- Stefano Brusco - Mafioso, companion of Moretti

- Raffaele di Gregorio - boss of a Camorra clan

- Raffaele's wife - actual clan leader

- Francesco, Marco, Riccardo - Mafiosi

- Gaetano - Mafioso

- Enrico - Mafioso

- Luca Rossi - art expert of the Camorra

- Sofia - wife of Luca

More or less important

- Jakob Bender - City archivist

- Michele - Pizzeria host

- Mr Myers - plays a role in the Cayman Islands

- Otto Schott - Munich gallery owner

- Edoardo Corelli - Milanese gallery owner

- Peter Marxner - bar owner

Chapter One

Death with style

Visitors are not yet to be seen this Wednesday. The Kunst-quartier will not open for another half hour. The caretaker is making his morning rounds. Is everything all right? Nothing is in order!

The caretaker is heading for the stairs down from the upper floor of the Osthaus Museum. He must have been surprised, because the light was still on upstairs. Had someone forgotten to turn it off last night? Then he looked over the beautifully crafted banister down into the hall with the marble Art Nouveau fountain and its five bowing male figures and the small fountain in the middle. The fountain has undergone a gruesome transformation. The white marble and the water are coloured red, and the five figures have been joined by another. A human body hangs above them. One of the figures has bored its way through this body.

Driven by horror, the caretaker rushes down the stairs, stumbles and almost falls on the last landing. Who is that lying there across the well in his blood? Then the caretaker is downstairs and can see it from the side. There lies the museum director Ricardo Sommer, pierced by Art Nouveau, and as dead as dead can be.

Shocked by the sight, the caretaker almost throws up. Then he runs up to the cash desk and shouts to the cashier already sitting there: "Call the police! Call the police!"

The cashier doesn't know what's happening to her, but well, if the caretaker wants it, she calls the police.

The police arrive quickly, because the police station is in the neighbourhood, on Prentzelstraße. The caretaker leads the two officers to the fountain. For them, too, such a sight is not an everyday occurrence. They are also shocked, because they know the museum director, he is well-known in the city.

"This is a case for the CID," one of the officers states, "it doesn't look like a natural death to me."

He pulls out his duty mobile phone and calls the relevant office: Criminal Investigation Department 11, Homicide, Death Investigations. It takes time for the investigators to arrive, because they first have to drive from the police headquarters on Hoheleye to the city.

Chief Inspector Günter Etsch has already seen a lot in his criminal career, but the bloody scene he now has before his eyes is new to him in its extremely bizarre nature. A corpse in the midst of a highly artistic environment, pierced by a marble statuette as if by a torpedo. And of course he also knows the dead man.

"My God, what happened there?" he muses aloud. "Did the man lean too far over the railing?"

Then he instructs the two policemen, who are still standing there dumbfounded: "Block off this part of the building! Searchers have no business here."

The policemen call for more help and equipment from the police station and practically seal off the entire museum building with the typical red and white police cordon tape with the words "Polizeiabsperrung" (police cordon) in big letters.

In the meantime, the police doctor has put on his latex gloves and begun an initial examination of the body. Even he has never experienced such a strange death.

"Can you say anything yet, doctor?" asks Etsch impatiently.

"But yes, my dear, the man is quite clearly dead," the doctor says seriously, but can hardly stifle a laugh. The investigators always want results, results, results, and preferably yesterday.

Etsch already knows these medical sayings and can no longer laugh about them. He needs facts, the sooner the better. The perpetrator or perpetrators have a head start that needs to be caught up. Otherwise it will become increasingly difficult to solve the case.

The police doctor, however, can already contribute insights.

"The man has been dead for about eight to nine hours, Chief Superintendent. And he did not fall of his own accord. He clearly received a hard blow to the back of the head. Without wanting to prejudge the forensic investigation, it was probably the contact with this fountain figure that caused his death. Of course, the blow could already have been fatal. We will find out."

Günter Etsch turns to his colleague standing next to him, Inspector Katharina Weil: "Then it must have happened at midnight, right? But what is a museum director doing in the museum at midnight?"

"If I knew," Katharina Weil shrugs. "I'm not familiar with the psyche of museum directors."

The two criminologists are now organising the forensics. The specialists have to examine practically the entire building for traces. How did the perpetrator(s) get into the building? Are there signs of a break-in? If not, did the director let them in? Otherwise, the search is on for possible fingerprints.

Fingerprints are still an essential means of evidence. Dactyloscopes, which are specially trained employees, compare fingerprints with fingerprints of suspects. This comparison is made possible by an identifying evaluation of the individually characteristic and unchanging features of the skin waves on the fingertips. Years ago, the experts had to painstakingly and very time-consumingly evaluate and record the results by sight.

Today, they are read in electronically on the computer and compared with the existing data. This procedure is called Automated Fingerprint Identification System (AFIS). In AFIS, an independent nationwide comparison is made with the stored fingerprints of all unsolved crimes and with all fingerprints stored for the purpose of the identification service. This has made it possible to multiply the speed of the comparison of traces.

On site, however, manual labour is still necessary. With a brush and special powder, all possible surfaces have to be dusted and the fingerprints that become visible have to be transferred onto adhesive foil. These are later scanned and entered into the computer.

However, only solid and smooth materials are suitable for trace investigation. The perpetrator does not always leave usable fingerprints. He could also have worn gloves.

In addition to fingerprints, DNA traces are also needed. The North Rhine-Westphalian police use the latest scientific findings and examination methods. Even the smallest amounts of body cells, such as saliva, blood or skin, are sufficient for the scientists at the State Criminal Police Office to conduct a molecular genetic examination and determine the DNA identification pattern of a crime scene trace or a person. In this analysis, only sections of the noncoding, i.e. the area of the DNA that does not contain genetic information, are examined. Individual external characteristics of the person thus remain protected.

Within a very short time, the results can be directly checked for consistency with the comparison material of suspected persons or the data stock of the DNA analysis file kept at the Federal Criminal Police Office.

The successes of recent times, especially in solving serious homicides and sexual offences, have confirmed the expectations of the police and justify the use of this procedure. Not infrequently, it has also been possible to exclude suspicion of a crime against a specific person beyond doubt by means of a DNA analysis.

The problem with all trace searches is that in a museum the existing traces can also come from the museum staff or from the visitors. It will be very difficult to narrow things down. You cannot assume that you will necessarily find clues in the databases.

But all this is routine and Etsch and Weil let the specialists do their work.

"We have to question the museum staff," Katha-rina Weil notes with unease. She doesn't like doing this work. Always the same questions: Did you see anything? Did you notice something? Do you know more about it?

Weil and Etsch go into the connecting entrance hall of the museum. All the employees seem to have gathered there. The shock is written all over their faces. The museum director Ricardo Sommer was popular with them. He was highly competent in art history and also enjoyed international recognition, but he did not wear his nose high at all. He often chatted with the supervisors and inquired about their personal circumstances. And he was not above occasionally sweeping away the leaves in front of the entrance in autumn, which fell in masses from the two tall trees in the museum courtyard. When the caretaker reproached him that as director he didn't have to do that, he regularly received the answer that without real life, all art was worthless.

The questioning of the museum employees does not yield any usable insights. How could they, none of them stay at their workplace at night.

"If you want to know what the director was doing in the museum that night, you'd better ask his deputy," says the second cashier.

That's right, Etsch thinks, there's also the deputy director, Dr Karin Schmitt. She is supposed to be a strange woman. He hasn't met her personally yet.

"Has the deputy director arrived yet?" Etsch asks the cashier.

"I don't know, she comes and goes as she pleases. She doesn't think much of a regular service, like the ones we have to run. Go over to the office above the restaurant. If you're lucky, she'll be there."

The cashier's voice sounds rather contemptuous, Katharina Weil thinks. The woman obviously doesn't care much for the deputy director.

Etsch and Weil make the short walk over to the museum office. When they step outside through the museum's automatic swinging door, the reporters are already waiting there. How do they know that something has happened here, Etsch wonders. The museum staff must have tipped them off. But no matter, it won't be possible to conceal it anyway. So he gives the most necessary information in scant words, while the photographer captures the two police officers in the picture.

"We are just starting the investigation. You will understand that we cannot tell them more. The di-rector of the Osthaus Museum was probably murdered, we found him dead."

"Can you tell us anything about the crime scene?" a reporter wants to know.

"For investigative tactical reasons, we don't give out any further explanations," says Etsch, while Katharina Weil rolls her eyes. Always the same thing!

"Can we at least look around the museum?"

"That's not possible. We are still searching for clues and the old building of the museum is closed until further notice."

Günter Etsch turns around, gives his colleague a sign and they make their way to the museum office. When they open the door on the office floor, a woman is taking off her coat.

She's arrived early, Etsch thinks, it's only 12 o'clock.

"Are you Mrs Schmitt?" he asks.

"Dr. Schmitt," says the woman, "Frau Dr. Schmitt."

Katharina Weil has just been waiting for that. If there's one thing she can't stand, it's arrogance.

"Well, Dr. Schmitt," she says, emphasising the title, "it seems that you have a flexible working time. Perhaps you haven't even noticed any drastic events in your museum."

"My working hours are none of your business," Dr Schmitt snaps audibly. "Who are you, anyway?"

"My name is Katharina Weil. I'm a detective with the Hagen CID and this is my colleague, Chief Inspector Günter Etsch."

"The CID in the museum? That's new. But what could have happened here? Did someone steal something, did I park wrong?"

You're not going to be happy, Katharina thinks.

"We don't know if anyone stole anything," says Etsch, "but maybe we can find out something from you. What is certain, however, is that your superior, museum director Ricardo Sommer, was murdered. The crime happened around midnight. Do you have any idea what Mr Sommer was doing in the museum at that time?"

Dr Schmitt's face remains expressionless. No trace of horror or even regret. Inside her it looks different.

"Am I the director's minder? Mr Sommer could do whatever he wanted, even go to the museum at night. If he was murdered during such a walk, that was just his risk. Someone could also kill me if I went for a walk at night."

Schmitt is certainly right about that, but it's certainly not normal in a museum, thinks Katharina Weil.

"If someone is murdered in a museum in the middle of the night, that's something else, isn't it?" she reproaches the deputy director. "Can't you say anything else about it? Did the director have any enemies? Who could he have met that night?"

"I already told you, I was not interested in what Sommer did. Therefore, I can't give you any information about his friends or enemies. I do the scientific work here at the museum, Sommer was the figurehead. Full stop. That's all I want to say about that."

"You don't seem to be interested in helping us with the investigation," Günter Etsch notes. "But I think we will have to question you more than once. For the time being, I would like to ask you to make an inventory. Have any works of art been stolen? That would at least be a motive for the murder."

"Yes, what do you think?" agitated Schmitt. "I can't waste my time with an inventory."

Now Etsch has his coffee on.

"If you don't comply with my request, I'll charge you with obstructing police work," he threatens her. "Otherwise, have a nice day. You don't seem too sorry about your dead director."

The two detectives leave the office and Katharina Weil slams the door emphatically behind her.

✓✓✓

When it comes to art in Hagen, the Osthaus Museum is the first address. It can look back on a long tradition and many confusions. Its founder, Karl Ernst Osthaus, associated his "Folkwang idea" with the idea that art and life could be reconciled.

The "Folkwang School of Painting" was founded as early as 1901. Artists such as Christian Rohlfs, Emil Rudolf Weiß, Jan Thorn Prikker and Milly Steger were invited to Hagen by Osthaus and had the opportunity to develop their talents here, freed from economic hardship. Emil Nolde called the museum a "sign of the heavens in western Germany".

In 1902, the Museum Folkwang in Hagen was opened as the world's first museum of modern art. The interior of the building was designed by Henry van de Velde. Karl Ernst Osthaus organised numerous exhibitions in the Museum Folk-wang, such as that of the "Brücke" in the summer of 1907, and maintained intensive contacts with artists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde and Alexander Archipenko.

In addition to works by Paul Cézanne, Anselm Feuerbach, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Ferdinand Hodler, Henri Matisse, George Minne, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Auguste Rodin, Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, it was above all the collections of European decorative arts and non-European art that made the museum's reputation in the early years.

Osthaus also endeavoured to shape social life through art in a broader sense. Thus he encouraged the founding of an artists' colony, workshops and a teaching institute. In this context, the "Hagen Silversmiths' Workshop" and the "Hagen Handicraft Seminar" were founded under the direction of J. L. Matthieu Lauweriks.

After the death of Karl Ernst Osthaus in 1921, his heirs sold the collection and the rights to the name to the Folk-wang-Museumsverein Essen and the city of Essen in 1922. The museum building in Hagen was converted into an office building by the Mark Municipal Electricity Works, so that a large part of the important interior furnishings were also lost. However, the painter Christian Rohlfs and his wife were able to keep their flat in the attic, as they were entitled to a lifelong right of residence.

The re-foundation of an art museum in Hagen was initiated by the artists' association "Hagenring" and the "Karl Ernst Osthaus-Bund". Initially, this became a "Christian-Rohlfs-Museum". For the first time, a museum named after a living modernist artist was dedicated to him. The municipal art museum in the rooms of the Karl Ernst Osthaus-Bund on Hochstraße opened on Saturday, 9 August 1930. At the end of 1934, however, at the instigation of the Nazis, the name Christian Rohlfs was removed and the museum was now only called "Städtisches Museum - Haus der Kunst".

In connection with the purges of German museums after the "Degenerate Art" exhibition, the Hagen Art Museum also lost a large part of its holdings, including about 400 works by Christian Rohlfs. Further holdings were lost in bombing raids during the Second World War and through looting at the end of the war.

When the museum reopened under the name Karl Ernst Osthaus Museum at the end of 1945, the collection had to be rebuilt. In 1955, the old Folkwang building on Hochstraße could be occupied again. A restoration or partial reconstruction of the Art Nouveau interior by Henry van de Velde was financed by donations and completed by the time the large Henry van de Velde exhibition opened in 1991. At the same time, a reorientation of the museum took place.

The Karl Ernst Osthaus Museum was closed from 2006 until the end of August 2009. During this time it was spatially expanded. The reopening under the name Osthaus Museum Hagen took place together with the completion and reopening of the Emil Schumacher Museum located right next door. Since then, both museums have formed the Kunstquartier Hagen.

The Kunstquartier Hagen is a place of contrasts. On the one hand, there is the Osthaus Museum, characterised by Art Nouveau, with its paintings of classical modernism and contemporary art; on the other, there is the hypermodern glass cube of the Emil Schumacher Museum with Emil Schumacher's informal works.

The new building of the Emil Schumacher Museum in particular is causing the financially weak city of Hagen a great deal of concern. New problems keep cropping up. The air conditioning doesn't work, the water supply has a legionella problem. On top of that, the number of visitors is extremely low, and not even the name Emil Schumacher can really inspire them. So the city administration came up with the idea of closing the two museums on Tuesday in addition to the traditional Monday. In the end, the visiting hours were cut. Instead of 10 a.m., it starts at 11 a.m. and ends at 6 p.m. The long Thursday, well established in other museums, was cancelled.

✓✓✓

Jakob Bender reads the newspaper. He reads the newspaper every morning when he is on duty, because Jakob Bender is the city archivist. He has to track down and archive everything that can be attributed to the city's history.

The Hagen City Archives were founded in 1929. In the years that followed, the holdings were considerably expanded. Today, the Stadtarchiv Hagen is one of the largest municipal archives in North Rhine-Westphalia.

The holdings of the City Archives cover a period from the Middle Ages through the early modern period to the present day. They document over 750 years of history of the city, its districts and the entire region. Over the decades, an extensive collection of newspapers has been built up in the city archives, which Jakob is now constantly adding to.

He used to read the Westfälische Rundschau and the Westfalenpost. Now it's enough to read only the Westfalenpost, because since the editorial office of the Westfälische Rundschau was dissolved, you read in it exactly what you read in the Westfalenpost. During the week he also skims the Wochenkurier and the Stadt-Anzeiger, advertising papers that appear twice a week. It seems a little nonsensical to Jakob Bender that these publications should also be archived. But well, the management of the Ha-gen Historical Centre, to which the city archive belongs, wants it that way.

Finally he arrives at the local section of the WP and is almost struck by it. In large letters, as large as one rarely sees in this newspaper, the headline jumps into his eyes: Murder in the museum - director murdered!

Jakob Bender feverishly reads through the article. He notices right away that the writers don't know anything for sure. They indulge in wild speculation. It all sounds a bit lurid, almost as if you were holding the Bild newspaper in your hands.

Jakob Bender is deeply shocked. Ricardo Sommer murdered! Unbelievable! He knew Sommer well. The museum director had often been here in the archive and had rummaged through the collected material with him. Back then, when he took over as museum director in Hagen, he was particularly interested in museum history, especially the time when the Folkwang Museum was sold to Essen by the Osthaus heirs. "How could they have done that?" he kept muttering and shaking his head. "If Osthaus had experienced that…"

Only recently, about a fortnight ago, Sommer was still in the Archiv. He asked if there was anything about looted art in connection with the Osthaus Museum. This is certainly a topic for all museum directors in Germany at the moment, since works of modern art in unimagined numbers and quality were found in the flat of the now deceased art collector Friede-mann Gründlich.

Every museum director is afraid of having looted art in his or her collection, art that was looted during the National Socialist era or "seized due to Nazi persecution". The victims of the looting were primarily Jews and those persecuted as Jews, both within the German Reich from 1933 to 1945 and in all the territories occupied by the Germans during the Second World War. The looting took place on the basis of a multitude of legal regulations and with the involvement of various authorities and institutions set up specifically for this purpose. The extent is estimated at 600,000 works of art. Up to 10,000 of them are said to have found their way into private or public collections through dark channels.

On the subject of looted art, however, the two were unable to find anything in any section of the archive related to the Hagen Museum. It seemed as if everything was fine with the collection.

Jakob Bender, however, had the impression that Sommer was not satisfied with the research despite the positive result. Somehow he seemed nervous and depressed. That was not his way. Bender knew him differently, he had always been open-hearted, fun-loving and sociable.

He had also learned a lot about Sommer. Sommer grew up in Florence, his father was a German in the diplomatic service abroad, his mother Italian. After graduating from high school, he studied art history. This excited him, because Florence in particular was and is the place where art is omnipresent.

Sommer received a well-founded overview of the history of Italian art, with special emphasis on the Renaissance in Florence. He was offered a comprehensive outline of the history, which came alive through practical observations in the city.

Ricardo Sommer successfully completed his studies and decided to seek his professional fortune as an art historian in Germany, where the museum landscape cannot exactly be described as meagre.

He got his first job at the Alte Pi-nakothek in Munich, where his extensive knowledge of the Renaissance was very useful. After a few years in Munich, he applied to become curator at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt. Despite his lack of a doctorate, he was accepted because he was particularly qualified. Now 700 years of European art history - from the Middle Ages through the Renaissance, Baroque and Modernism to the present day - lay within his sphere of activity.

In 2007, Ricardo Sommer had a new opportunity for his professional development. A new director was sought for the Karl Ernst Osthaus Museum in Hagen. He had already heard of this museum in Italy, because it was here that the Folkwang idea was founded and because it exhibited modern art worldwide for the first time. Sommer made the running. He took up his post in mid-September 2007 and put his heart and soul into becoming the director of the museum, which was soon to be known simply as the Osthaus Museum.

Ricardo Sommer had told the archivist Bender all this bit by bit during his visits to the city archives. Jakob Bender was now all the more moved by the terrible events. Who could have had an interest in eliminating such a friendly and committed person as Ricardo Sommer? And why? Jakob decides to pursue this case intensively.

✓✓✓

The chief detective and his colleague are sitting in their office on Hoheleye. Two days have passed since the museum director was found lying in his blood. So far, there are no clues to the background of the crime. Etsch and Weil are somewhat at a loss.

At least the results of the forensic medicine are already available. The museum director was apparently severely maltreated, as numerous haematomas scattered all over his body prove. The fatal blow, however, was a heavy blow with a pointed object that penetrated the top of the skull into the brain. Only afterwards was Ricardo Sommer apparently pushed over the Art Nouveau railing down onto the fountain.

The result of the forensics is rather unsatisfactory. At the top of the railing there were traces of blood that came from Sommer. There was a lot of spatter after the blow to the head. A lot of fingerprints were found, which is no wonder in a public museum. But not a single print could be matched. The murder weapon is also a mystery. It could have been something like a fire hook. But what kind of criminal takes a fire poker into a museum at night?

"I'll tell you something, Günter. That Frau Dr.," says Katharina Weil, emphasising Dr., "that Frau Dr. struck me as rather strange. Who reacts so coldly when one's direct superior, with whom one certainly has to work closely in a museum, is killed in such a terrible way?"

"Yes, a very strange person. I think we should take another look at her. Maybe she knows more than you think. Call the museum and make an appointment!"

Katharina Weil dials the museum number and is connected to the management. The secretary takes the call.

"Dr. Schmitt? She hasn't been here in the office for two days. She hasn't left a message either. I couldn't reach her by phone. Maybe you could give her a call. I'll give you her number."

Great, thinks the inspector.

"Frau Dr. has removed herself from the museum business," she explains to her puzzled colleague.

"What do you mean, removed?"

"She hasn't appeared in the office for two days, which is exactly since the murder happened. I'm calling her home now."

She dials the number given to her by the museum secretary. For minutes she only hears the dial tone. Nothing happens. Katharina Weil hangs up.

"Nothing can be done. Dr. might have gone on holiday," she says, sounding a little contemptuous.

"Anything is possible," says Etsch and looks up from his monitor. He has researched the database again to see if there have been similar cases before. The Hagen case, however, seems to be unique.

"It's no use, Katharina, we'll just have to go and see the good doctor. Do we know her address?"

"No, but I'll call the museum again."

Finally, the secretary gave her the address of Dr Karin Schmitt. She lives in Eppenhausen and has rented a house there.

Rather reluctantly, the two detectives set off.

✓✓✓

Jakob Bender can't shake the thought of Ricardo Sommer's murder. Why? What was behind it? Actually, it could only be about something in connection with art. Art mafia?

Over the past two days, the city archivist has been feverishly searching his archives for anything that even looked like museum news. So far, there has been nothing helpful.

Now he is standing in front of a filing cabinet in which municipal documents are stored. He has not yet studied them very closely, because they are rather boring. Accounts, income, expenditure, pages and pages. At the bottom of the last drawer, he discovers some documents that he hasn't even noticed yet. Carefully he takes them out, the paper is already rather crumbly.

There are five pages, which he spreads out on his table. Only gradually does he realise what he is reading. It is the report of an SS-Standartenführer Fröhlich. It is about the purges of the then "Städtisches Museum - Haus der Kunst" in connection with the "Degenerate Art" exhibition in Munich in 1937. The Hagen Art Museum was deprived of a large part of its holdings.

In February 1937, the SS man listed all the works of art that, according to the museum's inventory, were to be seized. In fact, there was a discrepancy. 53 works were not present. Neither the museum director Gerhard Brüns, a staunch Nazi, nor anyone else had an explanation for this. The director was able to credibly assure witnesses that all the works intended for the collection had been counted a week before the removal. The report of the Standartenführer ends with the note: Message to Mr. Adolf Ziegler, President of the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts.

Jakob Bender is flabbergasted. It was known that the museum had been cleared out by the Nazis. It was also known that a large number of works by Christian Rohlfs were among them. But the fact that there were no more paintings, despite an exact count, was new. This had never been heard of before. 53 paintings, possibly very valuable today, simply disappeared! And that in an allcontrolling Nazi state! Someone must have quickly moved the works of art aside and led both the museum directorate and the SS around by the nose. What had happened to the paintings? Was this a lead to Sommer's murder? Actually, Jakob Bender could hardly believe it. What should Ricardo Sommer have to do with these missing works of art after so many years?

✓✓✓

Weil and Etsch drive via Feithstraße and Haßleyer Straße to the Stirnband. There they finally find the house that the deputy museum director has allegedly rented. Significantly, it is one of those stately Art Nouveau houses that can be found there in the direct vicinity of the Hohenhof.

Etsch thinks that's where the circle closes.

The Hohenhof in Hagen-Eppenhausen was built between 1906 and 1908 to designs by Henry van de Velde for Karl Ernst Osthaus within the garden city of Hohenhagen. Today it is one of the sites of the Osthaus Museum of the City of Hagen, next to the Kunstquartier.

"Gosh," Katharina Weil snaps. "How much do you think the rent is for a building like this? And what do museum people actually earn?"

"I have no idea, but I'm sure you have to knit for a long time for that. Come on, let's ring the bell!"

They get out of their vehicle and walk along a flagstone path through the front garden to the front door. Even after ringing the bell again, nothing happens.

Günter Etsch walks to the corner of the house. A wide driveway leads to the back of the house. At the end of the path at the far end of the garden he sees a large wooden hut, more like a barn, with a large gate. Tyre marks indicate that the building is used as a garage. The gate is halfway open.

"Let's go around the house. I want to take a closer look at the barn back there."

From the back, the house looks just as closed off as it does from the front. You don't get the impression that anyone lives here. They quickly approach the gate and step over the threshold into the semidark interior. Your eyes have to get used to it.

The room is large and empty. The roof construction is held up by massive beams. Only when their gaze wanders do they realise it. At the back of the barn, a person is hanging from a ceiling beam. They hurry closer. Then they are struck. Up there, hanging by a thick rope, is Dr. Karin Schmitt and they know intuitively that she is beyond help. Dr Karin Schmitt is definitely dead.

Then they see something else. A photo is stuck to a vertical beam. As they approach, they realise that the photo shows an art nouveau window.

"I don't believe it," groans Etsch. "The entire museum management dead within two days. The director dies in a group of Art Nouveau figures and his deputy hangs from a beam next to an Art Nouveau photo in a barn behind an Art Nouveau house. What the hell does that mean?"

"Do you think the Schmitt committed suicide?" asks Weil.

"I absolutely don't believe that. How could she have hung herself up there without a ladder? That's much too high. Then she stuck the photo there herself? And why should she have killed herself? Because she didn't like Sommer? There's something else behind it, some system. But which one?"

They have no choice but to call their colleagues from Forensics, who are soon there and routinely go about their work.

✓✓✓

The next day, the headlines in the newspapers are all over the place. Not only the local Westfalenpost and Westfälische Rundschau report, even the Bild-Zeitung headlines something beside the facts: Gruesome murders in Art Nouveau museum. No one can remember anything similar ever happening in Hagen. Jakob Bender is stunned. Now Schmitt too, he thinks, what's going on in the museum?

He had hardly any contact with the deputy museum director, in fact he didn't know her at all. She hadn't been in office long either. An acquaintance who works in the museum workshop had told him that she was not particularly popular with the staff. Quite the opposite of Ricardo Sommer. Popular or not, she did not deserve such a death. Bender shakes his head.

For a long time he sits over the daily newspaper and ponders. Whether it all has to do with the pictures that disappeared during the Nazi era? Valuable pictures have always been the object of the most vicious attacks and crimes. Just think of the theft of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre in Paris by the 29-year-old Italian craftsman Vincenzo Peruggia in August 1911. For the Louvre, the theft meant a huge scandal. The government dismissed the museum director and for three weeks the story dominated the front pages of the newspapers.

Jakob Bender suspects that the press will continue to focus on the two recent murders for a long time, especially if the investigation drags on. He decides to look more closely into the matter of the pictures that disappeared back then, if that is at all possible after such a long time. He first has to find out who all worked at the museum in 1937.