Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: epubli

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

IT is far from my purpose to elaborate the material in this book, to interpret it, or to add to it. With much of the drama it contains I, being Ambassador of the United States at the time, was intimately familiar; much of the extraordinary personality disclosed here was an open book to me long ago because I knew well the man who now, at last, has written characteristically, directly and simply of that self for which I have a deep affection. For his autobiography I am responsible. Lives of Mussolini written by others have interests of sorts. "But nothing can take the place of a book which you will write yourself," I said to him. "Write myself?" He leaned across his desk and repeated my phrase in amazement. He is the busiest single individual in the world. He appeared hurt as if a friend had failed to understand.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 436

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

My Autobiography

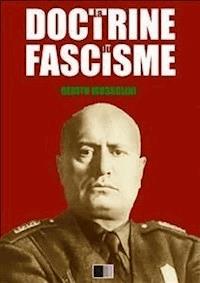

From a photograph by A. Badodi, Milan.

MUSSOLINI.

In his office at the Palazzo Chigi, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. When listening intently this is his attitude and expression.

My Autobiography

By

Benito Mussolini

With a Foreword byRichard Washburn Child

My Autobiography

CHAPTER I A SULPHUROUS LAND

CHAPTER III THE BOOK OF LIFE

CHAPTER IV WAR AND ITS EFFECT UPON A MAN

CHAPTER V ASHES AND EMBERS

CHAPTER VI THE DEATH STRUGGLE OF A WORN-OUT DEMOCRACY

CHAPTER VII THE GARDEN OF FASCISM

CHAPTER VIII TOWARD CONQUEST OF POWER

CHAPTER IX THUS WE TOOK ROME

CHAPTER X FIVE YEARS OF GOVERNMENT

CHAPTER XII THE FASCIST STATE AND THE FUTURE

INDEX

FOREWORDBy RICHARD WASHBURN CHILD

It is far from my purpose to elaborate the material in this book, to interpret it, or to add to it.

With much of the drama it contains I, being Ambassador of the United States at the time, was intimately familiar; much of the extraordinary personality disclosed here was an open book to me long ago because I knew well the man who now, at last, has written characteristically, directly and simply of that self for which I have a deep affection.

For his autobiography I am responsible. Lives of Mussolini written by others have interests of sorts.

“But nothing can take the place of a book which you will write yourself,” I said to him.

“Write myself?” He leaned across his desk and repeated my phrase in amazement.

He is the busiest single individual in the world. He appeared hurt as if a friend had failed to understand.

“Yes,” I said and showed him a series of headings I had written on a few sheets of paper.

“All right,” he said in English. “I will.”

It was quite like him. He decides quickly and completely.

So he began. He dictated. I advised that method because when he attempts to write in longhand he corrects and corrects and corrects. It would have been too much for him. So he dictated. The copy came back and he interlined the manuscript in his own hand—a dash of red pencil, and a flowing rivulet of ink—here and there.

When the manuscripts began to come to me I was troubled because mere literal translators lose the vigor of the man himself.

“What editing may I do?” I asked him.

“Any that you like,” he said. “You know Italy, you understand Fascism, you see me, as clearly as any one.”

But there was nothing much to do. The story came through as it appears here. It is all his and—what luck for all of us—so like him! Approve of him or not, when one reads this book one may know Mussolini or at least, if one’s vision is clouded, know him better. Like the book or not, there is not an insincere line in it. I find none.

Of course there are many things which a man writing an autobiography cannot see about himself or will not say about himself.

He is unlikely to speak of his own size on the screen of history.

Perhaps when approval or disapproval, theories and isms, pros and cons, are all put aside the only true measure of a man’s greatness from a wholly unpartisan view-point may be found in the answer to this question:

“How deep and lasting has been the effect of a man upon the largest number of human beings—their hearts, their thoughts, their material welfare, their relation to the universe?”

In our time it may be shrewdly forecast that no man will exhibit dimensions of permanent greatness equal to those of Mussolini.

Admire him or not, approve his philosophies or not, concede the permanence of his success or not, consider him superman or not, as you may, he has put to a working test, on great and growing numbers of mankind, programmes, unknown before, in applied spirituality, in applied plans, in applied leadership, in applied doctrines, in the applied principle that contents are more important than labels on bottles. He has not only been able to secure and hold an almost universal following; he has built a new state upon a new concept of a state. He has not only been able to change the lives of human beings but he has changed their minds, their hearts, their spirits. He has not merely ruled a house; he has built a new house.

He has not merely put it on paper or into orations; he has laid the bricks.

It is one thing to administer a state. The one who does this well is called statesman. It is quite another thing to make a state. Mussolini has made a state. That is super-statesmanship.

I knew him before the world at large, outside of Italy, had ever heard of him; I knew him before and after the moment he leaped into the saddle and in the days when he, almost single-handed, was clearing away chaos’ own junk pile from Italy.

But no man knows Mussolini. An Italian newspaper offered a prize for the best essay showing insight into the mystery of the man. Mussolini, so the story goes, stopped the contest by writing to the paper that such a competition was absurd, because he himself could not enter an opinion.

In spite of quick, firm decisions, in spite of grim determination, in spite of a well-ordered diagrammed pattern and plan of action fitted to any moment of time, Mussolini, first of all, above all and after all, is a personality always in a state of flux, adjusting its leadership to a world eternally in a state of flux.

Change the facts upon which Mussolini has acted and he will change his action. Change the hypotheses and he will change his conclusion.

And this perhaps is an attribute of greatness seldom recognized. Most of us are forever hoping to put our world in order and finish the job. Statesmen with some idea to make over into reality hope for a day when they can say: “Well, that’s done!” And when it is done,—often enough it is nothing. The bridges they have built are now useless, because the rivers have all changed their courses and humanity is already shrieking for new bridges. This is not an unhappy thought, says Mussolini. A finished world would be a stupid place—intolerably stupid.

The imagination of mere statesmen covers a static world.

The imagination of true greatness covers a dynamic world. Mussolini conceives a dynamic world. He is ready to go on the march with it, though it overturns all his structures, upsets all his theories, destroys all of yesterday and creates a screaming dawn of a to-morrow.

Opportunist is a term of reproach used to brand men who fit themselves to conditions for reasons of self-interest. Mussolini, as I have learned to know him, is an opportunist in the sense that he believes that mankind itself must be fitted to changing conditions rather than to fixed theories, no matter how many hopes and prayers have been expended on theories and programmes.

He has marched up several hills with the thousands and then marched down again. This strange creature of strange life and strange thoughts, with that almost psychopathic fire which was in saints and villains, in Napoleons, in Jeanne d’Arcs and in Tolstoys, in religious prophets and in Ingersolls, has been up the Socialist, the international, the liberal and the conservative hills and down again. He says: “The sanctity of an ism is not in the ism; it has no sanctity beyond its power to do, to work, to succeed in practice. It may have succeeded yesterday and fail to-morrow. Failed yesterday and succeed to-morrow. The machine first of all must run!”

I have watched, with a curiosity that has never failed to creep in on me, the marked peculiarities, physical and mental, of this man. At moments he is quite relaxed, at ease; and yet the unknown gusts of his own personality play on him eternally. One sees in his eyes, or in a quick movement of his body, or in a sentence suddenly ejaculated, the effect of these gusts, just as one sees wind on the surface of the water.

There is in his walk something of a prowl, a faint suggestion of the tread of the cat. He likes cats—their independence, their decision, their sense of justice and their appreciation of the sanctity of the individual. He even likes lions and lionesses, and plays with them until those who guard his life protest against their social set. His principal pet is a Persian feline which, being of aristocratic lineage, nevertheless exhibits a pride not only of ancestry but, condescendingly, of belonging to Mussolini. And yet, in spite of his own prowl, as he walks along in his riding-boots, springy, active, ready to leap, it seems, there is little else feline about him. One quality is feline, however—it is the sense of his complete isolation. One feels that he must always have had this isolation—isolation as a boy, isolation as a young radical, adventurer, lover, worker, thinker.

There is no understudy of Mussolini. There is no man, woman, or child who stands anywhere in the inner orbit of his personality. No one. The only possible exception is his daughter Edda. All the tales of his alliances, his obligations, his ties, his predilections are arrant nonsense. There are none—no ties, no predilections, no alliances, no obligations unpaid.

Financially? Lying voices said that he had been personally financed and backed by the industrialists of Italy. This is ridiculous to those who know. His salary is almost nothing. His own family—wife, children, are poor.

Politically? Whom could he owe? He has made and can unmake them all. He is free to test every officeholder in the whole of Italy by the yardstick of service and fitness. Beyond that I know not one political debt that he owes. He has tried to pay those of the past; I believe that the cynicism in him is based upon the failure of some who have been rewarded to live up to the trust put in them.

“But I take the responsibility for all,” says he. He says it publicly with jaws firm; he says it privately with eyes somewhat saddened.

He takes responsibility for everything—for discipline, for censorship, for measures which, were less rigor required, would appear repressive and cruel. “Mine!” says he, and stands or falls on that. It is an admirable courage. I could, if I wished, quote instance after instance of this acceptance—sometimes when he is not to blame—of the whole responsibility of the machine.

“Mine!” says he.

And in spite of any disillusionment he has suffered since I knew him first, he has retained his laugh—often, one is bound to say, a scornful laugh—and he has kept his faith in an ability to build up a machine—the machine of Fascism—the machine built not on any fixed theory but one intended by Mussolini to run—above all, to run, to function, to do, to accomplish, to fill the bottles with wine first, unlike the other isms, and put the labels on after.

Mussolini has superstitious faith in himself. He has said it. Not a faith in himself to make a personal gain. An assassin’s bullet might wipe him out and leave his family in poverty. That would be that. His faith is in a kind of destiny which will allow him, before the last chapter, to finish the building of this new state, this new machine—“the machine which will run and has a soul.”

The first time I ever saw him he came to my residence sometime before the march on Rome and I asked him what would be his programme for Italy. His answer was immediate: “Work and discipline.”

I remember I thought at that time that the phrase sounded a little evangelical, a phrase of exhortation. But a mere demagogue would never choose it. Wilson’s slogans of Rights and Peace and Freedom are much more popular and gain easier currency than sterner phrases. It is easier even for a sincere preacher, to offer soft nests to one’s followers; it is more difficult to excite enthusiasm for stand-up doctrines. Any analysis and weighing of Mussolini’s greatness must include recognition that he has made popular throughout a race of people, and perhaps for others, a standard of obligation of the individual not only exacting but one which in the end will be accepted voluntarily. Not only is it accepted voluntarily but with an almost spiritual ecstasy which has held up miraculously in Italy during years, when all the so-called liberals in the world were hovering over it like vultures, croaking that if it were not dead it was about to die.

It is difficult to lead men at all. It is still more difficult to lead them away from self-indulgence. It is still more difficult to lead them so that a new generation, so that youth itself, appears as if born with a new spirit, a new virility bred in the bones. It is difficult to govern a state and difficult to deal cleanly and strongly with a static programme applied to a static world; but it is more difficult to build a new state and deal cleanly and strongly with a dynamic programme applied to a dynamic world.

This man, who looks up at me with that peculiar nodding of his head and raising of the eyebrows, has done it. There are few in the world’s history who have. I had considered the phrase “Work and discipline” as a worthy slogan, as a good label for an empty bottle. Within six years this man, with a professional opposition which first barked like Pomeranians at his heels and then ran away to bark abroad, has made the label good, has filled the bottle, has turned concept into reality.

It is quite possible for those who oppose the concept to say that the reality of the new spirit of Italy and its extent of full acceptance by the people may exist in the mind of Mussolini, but does not spring out of the people themselves but it is quite untrue as all know who really know.

He throws up his somewhat stubby, meaty, short-fingered hands, strong and yet rather ghostlike when one touches them, and laughs. Like Roosevelt. No one can spend much time with him without thinking that after all there are two kinds of leaders—outdoor and indoor leaders—and that the first are somewhat more magnetic, more lasting and more boyish and likable for their power than the indoor kind.

Mussolini, like Roosevelt, gives the impression of an energy which cannot be bottled, which bubbles up and over like an eternally effervescent, irrepressible fluid. At these moments one remembers his playing of the violin, his fencing, his playful, mischievous humour, the dash of his courage, his contact with animals, his success in making gay marching songs for the old drab struggles of mankind with the soil, with the elements, with ores in the earth, and the pathways of the seas. In the somber conclusions of the student statesman and in the sweetness of the sentimentalist statesman there is little joy; unexpected joy is found in the leadership of a Mussolini. Battle becomes a game. The game becomes a romp. It is absurd to say that Italy groans under discipline. Italy chortles with it! It is victory!

He is a Spartan too. Perhaps we need them in the world to-day; especially that type whose first interest is the development of the power and the happiness of a race.

The last time I took leave of Mussolini he came prowling across the room as I went toward the door. His scowl had gone. The evening had come. There had been a half hour of quiet conversation. The strained expression had fallen from his face. He came toward me and rubbed his shoulder against the wall. He was relaxed and quiet.

I remembered Lord Curzon’s impatience with him long ago, when Mussolini had first come into power, and Curzon used to refer to him as “that absurd man.”

Time has shown that he was neither violent nor absurd. Time has shown that he is both wise and humane.

It takes the world a long time to see what has been dropped into the pan of its old scales!

In terms of fundamental and permanent effect upon the largest number of human beings—whether one approves or detests him—the Duce is now the greatest figure of this sphere and time. One closes the door when one leaves him, feeling, as when Roosevelt was left, that one could squeeze something of him out of one’s clothes.

He is a mystic to himself.

I imagine, as he reaches forth to touch reality in himself, he finds that he himself has gone a little forward, isolated, determined, illusive, untouchable, just out of reach—onward!

MY AUTOBIOGRAPHY

CHAPTER I A SULPHUROUS LAND

A

LMOST all the books published about me put squarely and logically on the first page that which may be called my birth certificate. It is usually taken from my own notes.

Well, then here it is again. I was born on July 29, 1883, at Varano di Costa. This is an old hamlet. It is on a hill. The houses are of stone, and sunlight and shade give these walls and roofs a variegated color which I well remember. The hamlet, where the air is pure and the view agreeable, overlooks the village of Dovia, and Dovia is in the commune, or county, of Predappio in the northeast of Italy.

It was at two o’clock Sunday afternoon when I came into the world. It was by chance the festival day of the patron saint of the old church and parish of Caminate. On the structure a ruined tower overlooks proudly and solemnly the whole plain of Forli—a plain which slopes gently down from the Apennines, with their snow-clad tops in winter, to the undulating bottoms of Ravaldino, where the mists gather in summer nights.

Let me add to the atmosphere of a country dear to me by bringing again to my memory the old district of Predappio. It was a country well known in the thirteenth century, giving birth to illustrious families during the Renaissance. It is a sulphurous land. From it the ripening grapes make a strong wine of fine perfume. There are many springs of iodine waters. And on that plain and those undulating foothills and mountain spurs, the ruins of mediæval castles and towers thrust up their gray-yellow walls toward the pale blue sky in testimony of the virility of centuries now gone.

Such was the land, dear to me because it was my soil. Race and soil are strong influences upon us all.

As for my race—my origin—many persons have studied and analyzed its hereditary aspects. There is nothing very difficult in tracing my genealogy, because from parish records it is very easy for friendly research to discover that I came from a lineage of honest people. They tilled the soil, and because of its fertility they earned the right to their share of comfort and ease.

Going further back, one finds that the Mussolini family was prominent in the city of Bologna in the thirteenth century. In 1270 Giovanni Mussolini was the leader of this warlike, aggressive commune. His partner in the rule of Bologna in the days of armored knights was Fulcieri Paolucci de Calboli, who belonged to a family from Predappio also, and even to-day that is one of the distinguished families.

The house at Varano di Costa, in Predappio, where Mussolini was born.

The destinies of Bologna and the internal struggles of its parties and factions, following the eternal conflicts and changes in all struggles for power, caused, at last, the exile of the Mussolinis to Argelato. From there they scattered into neighboring provinces. One may be sure that in that era their adventures were varied and sometimes in the flux of fortune brought them to hard times. I have never discovered news of my forbears in the seventeenth century. In the eighteenth century there was a Mussolini in London. Italians never hesitate to venture abroad with their genius or their labors. The London Mussolini was a composer of music of some note and perhaps it is from him that I inherit the love of the violin, which even to-day in my hands gives comfort to moments of relaxation and creates for me moments of release from the realities of my days.

Later, in the nineteenth century, the family tie became more clearly defined; my own grandfather was a lieutenant of the National Guard.

My father was a blacksmith—a heavy man with strong, large, fleshy hands. Alessandro the neighbors called him. Heart and mind were always filled and pulsing with socialistic theories. His intense sympathies mingled with doctrines and causes. He discussed them in the evening with his friends and his eyes filled with light. The international movement attracted him and he was closely associated with names known among the followers of social causes in Italy—Andrea Costa, Balducci, Amilcare, Cipriani and even the more tender and pastoral spirit of Giovanni Pascoli. So come and go men whose minds and souls are striving for good ends. Each conference seems to them to touch the fate of the world; each talisman seems to promise salvation; each theory pretends to immortality.

The Mussolinis had left some permanent marks. In Bologna there is still a street named for that family and not long ago a tower and a square bore the name. Somewhere in the heraldic records there is the Mussolini coat of arms. It has a rather pleasing and perhaps magnificent design. There are six black figures in a yellow field—symbols of valor, courage, force.

My childhood, now in the mists of distance, still yields those flashes of memory that come back with a familiar scene, an aroma which the nose associates with damp earth after a rain in the springtime, or the sound of footsteps in the corridor. A roll of thunder may bring back the recollection of the stone steps where a little child who seems no longer any part of oneself used to play in the afternoon.

Out of those distant memories I receive no assurance that I had the characteristics which are supposed traditionally to make parents overjoyed at the perfection of their offspring. I was not a good boy, nor did I stir the family pride or the dislike of my own young associates in school by standing at the head of my class.

I was then a restless being; I am still.

Then I could not understand why it is necessary to take time in order to act. Rest for restfulness meant nothing to me then any more than now.

I believe that in those youthful years, just as now, my day began and ended with an act of will—by will put into action.

Looking back, I cannot see my early childhood as being either praiseworthy or as being more than normal in every direction. I remember my father as a dark-haired, good-natured man, not slow to laugh, with strong features and steady eyes. I remember that near the house where I was born, with its stone wall with moss green in the crevices, there was a small brook and farther on a little river. Neither had much water in it, but in autumn and other seasons when there were unexpected heavy rains they swelled in fury and their torrents were joyous challenges to me. I remember them as my first play spots. With my brother, Arnaldo, who is now the publisher of the daily Popolo d’Italia, I used to try my skill as a builder of dams to regulate the current. When birds were in their nesting season I was a frantic hunter for their concealed and varied homes with their eggs or young birds. Vaguely I sensed in all this the rhythm of natural progress—a peep into a world of eternal wonder, of flux and change. I was passionately fond of young life; I wished to protect it then as I do now.

My greatest love was for my mother. She was so quiet, so tender, and yet so strong. Her name was Rosa. My mother not only reared us but she taught primary school. I often thought, even in my earliest appreciation of human beings, of how faithful and patient her work was. To displease her was my one fear. So, to hide from her my pranks, my naughtiness or some result of mischievous frolic, I used to enlist my grandmother and even the neighbors, for they understood my panic lest my mother should be disturbed.

The alphabet was my first practice in worldly affairs and I learned it in a rush of enthusiasm. Without knowing why, I found myself wishing to attend school—the school at Predappio, some two miles away. It was taught by Marani, a friend of my father. I walked to and fro and was not displeased that the boys of Predappio resented at first the coming of a stranger boy from another village. They flung stones at me and I returned their fire. I was all alone and against many. I was often beaten, but I enjoyed it with that universality of enjoyment with which boys the world around make friendship by battle and arrive at affection through missiles. Whatever was my courage, my body bore its imprints. I concealed the bruises from my mother to shelter her from the knowledge of the world in which I had begun to find expression and to which I supposed she was such a stranger. At the evening repast I probably often feared to stretch out my hand for the bread lest I expose a wound upon my young wrist.

After a while this all ended. War was over and the pretense of enmity—a form of play—faded into nothing and I had found fine schoolmates of my own age.

The call of old life foundations is strong. I felt it when only a few years ago a terrific avalanche endangered the lives of the inhabitants of Predappio. I took steps to found a new Predappio—Predappio Nuovo. My nature felt a stirring for my old home. And I remembered that as a child I had sometimes looked at the plain where the River Rabbi is crossed by the old highway to Mendola and imagined there a flourishing town. To-day that town—Predappio Nuovo—is in full process of development; on its masonry gate there is carved the symbol of Fascism and words expressing my clear will.

When I was graduated from the lower school I was sent to a boarding school. This was at Faenza, the town noted for its pottery of the fifteenth century. The school was directed by the Salesiani priests. I was about to enter into a period of routine, of learning the ways of the disciplined human herd. I studied, slept well and grew. I was awake at daylight and went to bed when the evening had settled down and the bats flew.

This was a period of bursting beyond the bounds of my own little town. I had begun to travel. I had begun to add length after length to that tether which binds one to the hearth and the village.

I saw the town of Forli—a considerable place which should have impressed me but failed to do so. But Ravenna! Some of my mother’s relatives lived in the plain of Ravenna and on one summer vacation we set out together to visit them. After all, it was not far away, but to my imagination it was a great journey—almost like a journey of Marco Polo—to go over hill and dale to the edge of the sea—the Adriatic!

I went with my mother to Ravenna and carefully visited every corner of that city steeped in the essences of antiquity. From the wealth of Ravenna’s artistic treasures there rose before me the beauty and fascination of her history and her name through the long centuries. Deep feelings remain now, impressed then upon me. I experienced a profound and significant enlarging of my concepts of life, beauty and the rise of civilizations. The tomb of Dante, inspiring in its quiet hour of noon; the basilica of San Apollinare; the Candiano canal, with the pointed sails of fishing-boats at its mouth; and then the beauty of the Adriatic moved me—touched something within me.

I went back with something new and undying. My mind and spirit were filled with expanding consciousness. And I took back also a present from my relatives. It was a wild duck, powerful in flight. My brother Arnaldo and I, on the little river at home, put forth patient efforts to tame the wild duck.

CHAPTER II MY FATHER

M

Y father took a profound interest in my development. Perhaps I was much more observed by his paternal attention than I thought. We became much more knit together by common interests as my mind and body approached maturity. In the first place I became fascinated by the steam threshing machines which were just then for the first time being introduced into our agricultural life. With my father I went to work to learn the mechanism, and tasted, as I had never tasted before, the quiet joy of becoming a part of the working creative world. Machinery has its fascinations and I can understand how an engineer of a railway locomotive or an oiler in the hold of a ship may feel that a machine has a personality, sometimes irritating, sometimes friendly, with an inexhaustible generosity and helpfulness, power and wisdom.

But manual labor in my father’s blacksmith shop was not the only common interest we shared. It was inevitable that I should find a clearer understanding of those political and social questions which in the midst of discussions with the neighbors had appeared to me as unfathomable, and hence a stupid world of words. I could not follow as a child the arguments of lengthy debates around the table, nor did I grasp the reasons for the watchfulness and measures taken by the police. But now in an obscure way it all appeared as connected with the lives of strong men who not only dominate their own lives but also the lives of their fellow creatures. Slowly but fatally I was turning my spirit and my mind to new political ideals destined to flower for a time.

I began with young eyes to see that the tiny world about me was feeling uneasiness under the pinch of necessity. A deep and secret grudge was darkening the hearts of the common people. A country gentry of mediocrity in economic usefulness and of limited intellectual contribution were hanging upon the multitudes a weight of unjustified privileges. These were sad, dark years not only in my own province but for other parts of Italy. I must have the marks upon my memory of the resentful and furtive protests of those who came to talk with my father, some with bitterness of facts, some with a newly devised hope for some reform.

It was then, while I was still in my early teens, that my parents, after many serious talks, ending with a rapid family counsel, turned the rudder of my destiny in a new direction. They said that my manual work did not correspond to their ambitions for me, to their ability to aid me, nor did it fit my own capacities. My mother had a phrase which remains in my ears: “He promises something.”

From a photograph by A. Badodi, Milan.

Mussolini’s mother and father, Rosa and Alessandro Mussolini.

At the time I was not very enthusiastic about that conclusion; I had no real hunger for scholastic endeavor. I did not feel that I would languish if I did not go to a normal school and did not prepare to become a teacher. But my family were right. I had developed some capacities as a student and could increase them.

I went to the normal school at a place called Forlimpopoli. I remember my arrival in that small city. The citizens were cheerful and industrious, good at bargaining—tradesmen and middlemen. The school, however, had a greater distinction; it was conducted by Valfredo Carducci, brother of the great writer Giosue Carducci, who at that time was harvesting his laurels because of his poetry and his inspiration drawn from Roman classicism.

There was a long stretch of study ahead of me; to become a master—to have a teacher’s diploma—meant six years of books and pencils, ink and paper. I confess that I was not very assiduous. The bright side of those years of preparation to be a teacher came from my interest in reforming educational methods, and even more in an interest begun at that time and maintained ever since, an intense interest in the psychology of human masses—the crowd.

I was, I believe, unruly; and I was sometimes indiscreet. Youth has its passing restlessness and follies. Somehow I succeeded in gaining forgiveness. My masters were understanding and on the whole generous. But I have never been able to make up my mind how much of the indulgence accorded to me came from any hope they had in me or how much came from the fact that my father had acquired an increasing reputation for his moral and political integrity.

So the diploma came to me at last. I was a teacher! Many are the men who have found activity in political life who began as teachers. But then I saw only the prospect of the hard road of job hunting, letters of recommendation, scraping up a backing of influential persons and so on.

In a competition for a teacher’s place at Gualtieri, in the province of Reggio Emilia, I was successful. I had my taste of it. I taught for a year. On the last day of the school year I dictated an essay. I remember its thesis. It was: “By Persevering You Arrive.” For that I obtained the praise of my superiors.

So school was closed. I did not want to go back to my family. There was a narrow world for me, with affection to be sure, but restricted. There in Predappio one could neither move nor think without feeling at the end of a short rope. I had become conscious of myself, sensitive to my future. I felt the urge to escape.

Money I had not—merely a little. Courage was my asset. I would be an exile. I crossed the frontier; I entered Switzerland.

It was in this wander-life, now full of difficulties, toil, hardship and restlessness, that developed something in me. It was the milestone which marked my maturity. I entered into this new era as a man and politician. My confident soul began to be my support. I conceded nothing to pious demagoguery. I allowed myself, humble as was my figure, to be guided by my innate proudness and I saw myself in my own mental dress.

To this day I thank difficulties. They were more numerous than the nice, happy incidents. But the latter gave me nothing. The difficulties of life have hardened my spirit. They have taught me how to live.

For me it would have been dreadful and fatal if on my journey forward I had by chance fallen permanently into the chains of comfortable bureaucratic employment. How could I have adapted myself to that smug existence in a world bristling with interest and significant horizons? How could I have tolerated the halting progress of promotions, comforted and yet irritated by the thoughts of an old-age pension at the end of the dull road? Any comfortable cranny would have sapped my energies. These energies which I enjoy were trained by obstacles and even by bitterness of soul. They were made by struggle, not by the joys of the pathway.

My stay in Switzerland was a welter of difficulties. It did not last long, but it was angular, with harsh points. I worked with skill as a laborer. I worked usually as a mason and felt the fierce, grim pleasure of construction. I made translations from Italian into French and vice versa. I did whatever came to hand. I looked upon my friends with interest or affection or amusement.

Above all, I threw myself headforemost into the politics of the emigrant—of refugees, of those who sought solutions.

In politics I never gained a penny. I detest those who live like parasites, sucking away at the edges of social struggles. I hate men who grow rich in politics.

I knew hunger—stark hunger—in those days. But I never bent myself to ask for loans and I never tried to inspire the pity of those around me, nor of my own political companions. I reduced my needs to a minimum and that minimum—and sometimes less—I received from home.

With a kind of passion, I studied social sciences. Pareto was giving a course of lectures in Lausanne on political economy. I looked forward to every one. The mental exercise was a change from manual labor. My mind leaped toward this change and I found pleasure in learning. For here was a teacher who was outlining the fundamental economic philosophy of the future.

Between one lesson and another I took part in political gatherings. I made speeches. Some intemperance in my words made me undesirable to the Swiss authorities. They expelled me from two cantons. The university courses were over. I was forced into new places, and not until 1922 at the Conference of Lausanne, after I was Premier of Italy, did I see again some of my old haunts, filled with memories colorful or drab.

To remain in Switzerland became impossible. There was the yearning for home which blossoms in the hearts of all Italians. Furthermore, the compulsory service in the army was calling me. I came back. There were greetings, questions, all the incidents of the return of an adventurer—and then I joined the regiment—a Bersaglieri regiment at the historic city of Verona. The Bersaglieri wear green cock feathers in their hats; they are famous for their fast pace, a kind of monotonous and ground-covering dogtrot, and for their discipline and spirit.

I liked the life of a soldier. The sense of willing subordination suited my temperament. I was preceded by a reputation of being restless, a fire eater, a radical, a revolutionist. Consider then the astonishment of the captain, the major, and my colonels, who were compelled to speak of me with praise! It was my opportunity to show serenity of spirit and strength of character.

Verona, where my regiment was garrisoned, was and always will remain a dear Venetian city, reverberating with the past, filled with suggestive beauties. It found in my own temperament an echo of infinite resonance. I enjoyed its aromas as a man, but also as a private soldier I entered with vim into all the drills and the most difficult exercises. I found an affectionate regard for the mass, for the whole, made up of individuals, for its maneuvers and the tactics, the practice of defense and attack.

My capacity was that of a simple soldier; but I used to weigh the character, abilities and individualities of those who commanded me. All Italian soldiers to a certain extent do this. I learned in that way how important it is for an officer to have a deep knowledge of military matters and to develop a fine sensitiveness to the ranks, and to appreciate in the masses of our men our stern Latin sense of discipline and to be susceptible to its enchantments.

I can say that in every regard I was an excellent soldier. I might have taken up the courses for noncommissioned officers. But destiny, which dragged me from my father’s blacksmith shop to teaching and from teaching to exile and from exile to discipline, now decreed that I should not become a professional soldier. I had to ask for leave. At the time I swallowed the greatest sorrow in my life; it was the death of my mother.

One day my captain took me aside. He was so considerate that I felt in advance something impending. He asked me to read a telegram. It was from my father. My mother was dying! He urged my return. I rushed to catch the first train.

I arrived too late. My mother was in death’s agony. But from an almost imperceptible nod of her head I realized that she knew I had come. I saw her endeavor to smile. Then her head slowly drooped and she had gone.

All the independent strength of my soul, all my intellectual or philosophical resources—even my deep religious beliefs—were helpless to comfort that great grief. For many days I was lost. From me had been taken the one dear and truly near living being, the one soul closest and eternally adherent to my own responses.

Words of condolence, letters from my friends, the attempt to comfort me by other members of the family, filled not one tiny corner of that great void, nor opened even one fraction of an inch of the closed door.

My mother had suffered for me—in so many ways. She had lived so many hours of anxiety for me because of my wandering and pugnacious life. She had predicted my ascent. She had toiled and hoped too much and died before she was yet forty-eight years old. She had, in her quiet manner, done superhuman labors.

She might be alive now. She might have lived and enjoyed, with the power of her maternal instinct, my political success. It was not to be. But to me it is a comfort to feel that she, even now, can see me and help me in my labors with her unequaled love.

I, alone, returned to the regiment. I finished my last months of military service. And then my life and my future were again distended with uncertainty.

I went to Opeglia as a teacher again, knowing all the time that teaching did not suit me. This time I was a master in a middle school. After a period, off I went with Cesare Battisti, then chief editor of the Popolo. Later he was destined to become one of the greatest of our national heroes—he who gave his life, he who was executed by the enemy Austrians in the war, he who then was giving his thought and will to obtaining freedom of the province of Trento from the rule of Austria. His nobility and proud soul are always in my memory. His aspirations as a socialist-patriot called to me.

One day I wrote an article maintaining that the Italian border was not at Ala, the little town which in those days stood on the old frontier between our kingdom and the old Austria. Whereupon I was expelled from Austria by the Imperial and Royal Government of Vienna.

I was becoming used to expulsions. Once more a wanderer, I went back to Forli.

The itch of journalism was in me. My opportunity was before me in the editorship of a local socialist newspaper. I understood now that the Gordian knot of Italian political life could only be undone by an act of violence.

Therefore I became the public crier of this basic, partisan, warlike conception. The time had come to shake the souls of men and fire their minds to thinking and acting. It was not long before I was proclaimed the mouthpiece of the intransigent revolutionary socialist faction. I was only twenty-nine years old when at Reggio Emilia at the Congress in 1912, two years before the World War began, I was nominated as director of the Avanti. It was the only daily of the socialist cause and was published in Milan.

I lost my father just before I left for my new office. He was only fifty-seven. Nearly forty of those years had been spent in politics. His was a rectangular mind, a wise spirit, a generous heart. He had looked into the eyes of the first internationalist agitators and philosophers. He had been in prison for his ideas.

The Romagna—that part of Italy from which we all came—a spirited district with traditions of a struggle for freedom against foreign oppressions—knew my father’s merit. He wrestled year in and year out with endless difficulties and he had lost the small family patrimony by helping friends who had gone beyond their depth in the political struggle.

Prestige he had among all those who came into contact with him. The best political men of his day liked him and respected him. He died poor. I believe his foremost desire was to live to see his sons correctly estimated by public opinion.

At the end he understood at last that the old eternal traditional forces such as capital could not be permanently overthrown by a political revolution. He turned his attention at the end toward bettering the souls of individuals. He wanted to make mankind true of heart and sensitive to fraternity. Many were the speeches and articles about him after his death; three thousand of the men and women he had known followed his body to the grave. My father’s death marked the end of family unity for us, the family.

CHAPTER III THE BOOK OF LIFE

I

PLUNGED forward into big politics when I settled in Milan at the head of the Avanti. My brother Arnaldo went on with his technical studies and my sister Edvige, having the offer of an excellent marriage, went to live with her husband in a little place in Romagna called Premilcuore. Each one of us took up for himself the torn threads of the family. We were separated, but in touch. We did not reunite again, however, until August 1914, when we met to discuss politics and war. War had come—war—that female of dreads and fascinations.

Up till then I had worked hard to build up the circulation, the influence and the prestige of the Avanti. After some months the circulation had increased to more than one hundred thousand.

I then had a dominant situation in the party. But I can say that I did not yield an inch to demagoguery. I have never flattered the crowd, nor wheedled any one; I spoke always of the costs of victories—sacrifice and sweat and blood.

I was living most modestly with my family, with my wife Rachele, wise and excellent woman who has followed me with patience and devotion across all the wide vicissitudes of my life. My daughter Edda was then the joy of our home. We had nothing to want. I saw myself in the midst of fierce struggle, but my family did represent and always has represented to me an oasis of security and refreshing calm.

Those years before the World War were filled by political twists and turns. Italian life was not easy. Difficulties were many for the people. The conquest of Tripolitania had exacted its toll of lives and money in a measure far beyond our expectation. Our lack of political understanding brought at least one riot a week. During one ministry of Giolitti I remember thirty-three. They had their harvest of killed and wounded and of corroding bitterness of heart. Riots and upheavals among day laborers, among the peasants in the valley of the Po, riots in the south—even separatist movements in our islands. And in the meantime, above all this atrophy of normal life, there went on the tournament and joust of political parties struggling for power.

I thought then, as I think now, that only the common denominator of a great sacrifice of blood could have restored to all the Italian nation an equalization of rights and duties. The attempt at revolution—the Red Week—was not revolution as much as it was chaos. No leaders! No means to go on! The middle class and the bourgeoisie gave us another picture of their insipid spirit.

We were in June then, picking over our own affairs with a microscope.

Suddenly the murder of Serajevo came from the blue.

In July—the war.

Up till that event my progress had been somewhat diverse, my growth of capacity somewhat varied. In looking back one has to weigh the effect upon one of various influences commonly supposed powerful.

It is a general conviction that good or bad friends can decisively alter the course of a personality. Perhaps it may be true for those fundamentally weak in spirit whose rudders are always in the hands of other steersmen. During my life, I believe, neither my school friends, my war friends, nor my political friends ever had the slightest influence upon me. I have listened always with intense interest to their words, their suggestions and sometimes to their advice, but I am sure that whenever I took an extreme decision I have obeyed only the firm commandment of will and conscience which came from within.

I do not believe in the supposed influence of books. I do not believe in the influence which comes from perusing the books about the lives and characters of men.

For myself, I have used only one big book.

For myself, I have had only one great teacher.

The book is life—lived.

The teacher is day-by-day experience.

The reality of experience is far more eloquent than all the theories and philosophies on all the tongues and on all the shelves.

I have never, with closed eyes, accepted the thoughts of others when they were estimating events and realities either in the normal course of things or when the situation appeared exceptional. I have searched, to be sure, with a spirit of analysis the whole ancient and modern history of my country. I have drawn parallels because I wanted to explore to the depths on the basis of historical fact the profound sources of our national life and of our character, and to compare our capacities with those of other people.

For my supreme aim I have had the public interest. If I spoke of life I did not speak of a concept of my own life, my family life or that of my friends. I spoke and thought and conceived of the whole Italian life taken as a synthesis—as an expression of a whole people.

I do not wish to be misunderstood, for I give a definite value to friendship, but it is more for sentimental reasons than for any logical necessity either in the realm of politics or that of reasoning and logic. I, perhaps more than most men, remember my school friends. I have followed their various careers. I keep in my memory all my war friends, and teachers and superiors and assistants. It makes little difference whether these friendships were with commanding officers or with typical workers of our soil.

On my soldier friends the life of trench warfare—hard and fascinating—has left, as it has upon me, a profound effect. Great friendships are not perfected on school benches, nor in political assemblies. Only in front of the magnitude and the suggestiveness of danger, only after having lived together in the anxieties and torments of war, can one weigh the soundness of a friendship or measure in advance how long it is destined to go on.

In politics, Italian life has had a rather short panorama of men. All know one another. I have not forgotten those who in other days were my companions in the socialistic struggle. Their friendship remains, provided they on their part acknowledge the need to make amends for many errors, and provided they have been able to understand that my political evolution has been the product of a constant expansion, of a flow from springs always nearer to the realities of living life and always further away from the rigid structures of sociological theorists.

My Fascist friends live always in my thoughts. I believe the younger ones have a special place there. The organization of Fascism was marked and stamped with youth. It has youth’s spirit and it gathered youth, which, like a young orchard, has many years of productiveness for the future.

Though it appears that the obligations of governing increase around me every day, I never forget those who were with me—the generous and wise builders, the unselfish and faithful collaborators, the devoted soldiers of a new Fascist Italy. I follow step by step their personal and public fortunes.