18,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Serie: Drucker Foundation Future Series

- Sprache: Englisch

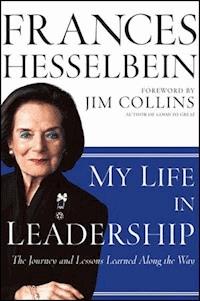

In a clear and compelling voice, Frances Hesselbein delivers key leadership lessons. Tracing her own development as a leader, she narrates the critical moments that shaped her personally and professionally: from her childhood in Pennsylvania, to moving up from Girl Scout troop leader to Girl Scout CEO, to founding and leading the Leader to Leader Institute, to her friendships and experiences with some of the greatest leaders and thinkers of our time. Each chapter includes an inspirational story, a key lesson and how to apply it to daily life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 300

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Foreword

Introduction: Being Called Forward

The Beginning of My Journey

Learn by Doing

Part One: Roots

Chapter 1: Stories of Family, Lessons of Love

Lessons of Love and Family

My Father

My Husband

Chapter 2: Embrace the Defining Moment

Take Care of Others

Respect for All

Fighting Discrimination

A Part of My Life and Work

Preaching Won't Do the Job

Chapter 3: Defining Yourself with the Power of No

The Power of No

The White House Is Calling

The Power of No for Organizations

Part Two: My Leadership Journey

Chapter 4: My Management Education

The Girls and the Team Approach

Carry a Big Basket

The Door That Opened Over Lunch

What It Means to Belong

What It Means to Belong

Chapter 5: New York Calls

Choose Your Battles

Inclusion

Releasing the Human Spirit

Chapter 6: Challenging the Gospel

Circular Management

Transforming a Large and Complex Organization

Managing the Transformation

Chapter 7: Becoming a Change Agent

Life-Size Learning

Get Feedback

Respect Feelings

Timing Is Everything

Chapter 8: Finding Out Who You Are

Staying Cool

Prepare for the Unknown

Chapter 9: My Journey with Peter Drucker

Keeping the Faith

Redefining the Social Sector

Peter's Qualities

Peter Drucker's Interview with Frances Hesselbein at the Girl Scout Edith Macy Conference Center, September 1988

Chapter 10: The Indispensable Partnership—Governance and Management, Board and Staff

The Power of Partnership

The Philosophy of No Surprises

Critical Questions

Planning, Policy, and Review

Exemplary Board–CEO Partnerships

Chapter 11: Strengthening the Leadership of the Social Sector

Establishing the Peter F. Drucker Foundation for Nonprofit Management

A Magnet for Talent

Challenges and Accomplishments

Chapter 12: Adventures Around the World

Love, Faith, and Peace to Us All

The Ocean of the Future

Seeing Yourself in Perspective

Part Three: Concerns and Celebrations

Chapter 13: To Serve Is to Live

Pillars of Democracy

How Do We Begin?

Rock Climbers

Chapter 14: Seeing and Listening

The Art of Listening

Seeing Things Whole

The Big Picture

Chapter 15: Leaders of the Future

The Crucible Generation

Express Yourself

Mentoring

Faces in the Crowd

Light a Fire

Chapter 16: Conclusion: Shine a Light

Jim Collins Interviews Frances Hesselbein at the Living Leadership Conference, Atlanta, Georgia, October 20, 2004

About the Author

Index

Copyright © 2011 by Frances Hesselbein. All rights reserved.

Published by Jossey-Bass

A Wiley Imprint

989 Market Street, San Francisco, CA 94103-1741—www.josseybass.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008, or online at www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

The “Girl Scouts” name, mark, and all associated trademarks and logo types, including the “Trefoil Design,” are owned by the Girl Scouts of the USA and used by permission.

Readers should be aware that Internet Web sites offered as citations and/or sources for further information may have changed or disappeared between the time this was written and when it is read.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

Jossey-Bass books and products are available through most bookstores. To contact Jossey-Bass directly call our Customer Care Department within the U.S. at 800-956-7739, outside the U.S. at 317-572-3986, or fax 317-572-4002.

Jossey-Bass also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hesselbein, Frances.

My Life in Leadership: The Journey and Lessons Learned Along the Way / Frances Hesselbein; foreword by Jim Collins.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-470-90573-9

1. Hesselbein, Frances. Women chief executive officers—United States—Biography. 3. Girl Scouts of the United States of America—Management.

4. Peter F. Drucker Foundation for Nonprofit Management. 5. Leadership.

I. Title.

HC102.5.H47A3 2011

658.0092–dc22

[B] 2010045733

I am deeply grateful to all who have helped me on my journey. Many are noted in the pages that follow, but there are far more who have blessed my life whom I could not recognize in this account (including the countless young people I meet on campuses and academies across the nations, who always give me new energy and new hope). This book is dedicated to all of them, whether named or not, around the world. They are our future.

This book also is dedicated to the men and women in uniform, past, present, and future, whose selfless service has sustained the democracy since the beginning of our country. My father, my husband, my brother, and my son John are part of this sturdy band. They are an inspiration to us all and teach us that service is a privilege, a remarkable opportunity. To serve is to live.

Foreword

In October of 2007, I sat with Frances Hesselbein in an enclosed conference room—no windows, maps on the wall, literally bombproof. We'd come together to spend time with the general officers of the 82nd Airborne at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. At the other end of the table sat the commander, General Lloyd J. Austin III, six-foot-four, a muscular two-hundred-plus pounds, winner of a Silver Star for gallantry in combat, responsible for thirty-five thousand soldiers, the power of the man amplified by his calm and quiet. On either side of Austin sat about a dozen one- and two-star generals, along with some colonels, in Army fatigues, all with on-the-ground experience in places like Iraq and Afghanistan.

General Austin had thought hard about this day, part of a final “get ready” time before his command redeployed to Iraq. This was their third deployment to that country. He wanted something special to inspire his general officers as they left their families once again, in service. His dream: a visit and leadership session from Frances Hesselbein. General Austin called and asked if I would come to Fort Bragg and engage Frances in a conversation with the generals.

General Austin began the meeting, “We are so fortunate to have with us one of the great leaders in America, Frances Hesselbein.” The Army generals hushed, and I began to ask Frances questions about leadership, based on her experiences leading the Girl Scouts of the USA back to greatness, earning her a spot on the cover of Business Week as America's best manager. Here sat gruff and rumble general officers who'd chosen to jump out of airplanes and lead combat battalions as a career, men who carry personal responsibility for the lives of thousands of young men and women. In business, failed leadership loses money; in the military, failed leadership loses lives.

As Frances talked, the generals sat utterly riveted, for two full hours. Diminutive, no more than five-foot-two, she held a commanding presence like Yoda dispensing wisdom to a gathering of Jedi knights. At the end of her session, the general officers spontaneously shouted Hooah!

It matters not the group—Fortune 500 CEOs, philanthropists, college students, social sector leaders, or military general officers in a war zone—Frances has the same effect on people. She inspires and teaches, not just because of what she says, but because of who she is. Leadership, she teaches, begins not with what you do, but with who you are. What are your values? What do you serve? What makes you get up every day and bring positive, go-forward tilt to everything and everyone you touch? She believes to her core the U.S. Army idea of “Be - Know - Do.” Because we cannot predict what challenges we will face, the most important preparation for leadership lies in developing personal character; you can learn the rest along the way.

In this book, Hesselbein shares her own story, her own life journey into a person of character. She describes the forces that shaped her, including a family that instilled in her the belief that “to serve is to live.” Like many great leaders, she did not choose her responsibilities. When her father died, she returned home from school and assumed responsibility for the family. Later in life, she led a Girl Scout council in Johnstown, Pennsylvania. A couple of members of the local council took her to lunch one day, and one of them said, “We've found the perfect leader to be our new executive director of the Talus Rock Girl Scout Council.”

“Oh, that's wonderful,” exclaimed Frances. “Who?”

“You, Frances.”

“But I am a volunteer, not really prepared for this,” she replied.

“We think you are the right person,” they pressed.

“OK,” she finally relented, “I'll do this for six months while we look for a real leader.”

Six years later, she would leave Pennsylvania to become the CEO of the Girl Scouts of the USA. She would hold the position for thirteen years, the first chief executive to come from the field in sixty-four years, and would lead a great turnaround. The Girl Scouts of the USA faced eight straight years of declining membership and turned to Frances to reverse the slide. In taking the role, she never thought of herself as being “on top” of the organization, but in service to a cause larger than herself. One of her greatest accomplishments came in leading the Girl Scouts to become a place where girls of all origins, whether black, white, Latina, American Indian, or Eskimo, and any form of immigrant, regardless of race or culture, could find themselves. Under her leadership, the Girl Scouts regained momentum, reaching a membership of 2.25 million girls with a workforce (mainly volunteers) of 780,000. Equally important, she set up the organization to be successful beyond her, with an ever increasing size and diversity of members and volunteers.

After the Girl Scouts, Frances became the founding president and CEO of the Peter F. Drucker Foundation for Nonprofit Management, now the Leader to Leader Institute, inspired by her friend and mentor Peter Drucker. She has spent the last two decades multiplying her leadership threefold: her own leadership example multiplied by teaching leadership to others multiplied by leading an organization dedicated to inspired leadership in the business and social sectors. In all my years of working with leaders, from nonprofits to Fortune 500 companies, from government executives to philanthropists, from military leaders to school principals, I have met not a single person who has had a larger multiplicative effect than Frances. In recognition of her extraordinary multiplicative contributions, she received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the United States of America's highest civilian honor, in 1998.

I believe that people exude either “positive valence” or “negative valence.” Positive-valence people increase the energy in the room every time they enter. Frances has been for me a “double positive valence”—adding energy every time I have the chance to be with her. It's like plugging into a human power source.

During one of our long conversations, I asked Frances how she endured the burdens of leadership and sustained her energy.

“Burden?” She looked puzzled. “Burden? Oh no, leadership is never a burden; it is a privilege.”

“But how do you sustain the energy for leadership? We all have limits, but I've never seen you reach yours.”

“Everything I have been called to do gives me energy. The greater the call, the greater the energy; it comes from outside me.”

And perhaps that is one of the great secrets of leadership that Frances teaches with her life. If you are open to being called, if you see service not as a cost to your life but as life itself, then you cannot help but be caught in a giant self-reinforcing circle. You are called to leadership, and your energy rises to the call, you then lead effectively and are called to greater responsibility, your energy rises again to the call, and so it goes. The late John Gardner (author of the classic book Self-Renewal and founder of Common Cause) taught me that one absolute requirement for leadership is an extraordinarily high energy level. Frances taught me that one of the greatest sources of energy is leadership done in the spirit of service.

It is no surprise, then, that in 2009, one of our greatest leadership training grounds, the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, made Frances Hesselbein the Class of 1951 Chair for the Study of Leadership. I'm certain that General Austin, himself a West Point graduate, feels that the cadets have been blessed by a great stroke of good fortune to have Frances as a teacher and mentor. I picture her sitting with these young leaders, a walking exemplar of the West Point “Be - Know - Do” philosophy, modeling the Big Lesson: no matter what knocks you down, you get up and go forward. You might be appalled by horrifying events, but never discouraged. You might need to deal with mean-spirited and petty people along the way, but never lose your own gracious manner. You might need to confront a litany of brutal facts and destabilizing uncertainties, but it is your responsibility, as a leader, to always shine a light.

Jim Collins

Boulder, Colorado

December 2010

Introduction: Being Called Forward

On January 15, 1998, I was at the White House, seated in the East Room, to receive our country's highest civilian award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom. I was overwhelmed that day—and I am still overwhelmed. In the front row before a low stage, I sat with other honorees, including David Rockefeller, Admiral Zumwalt, Brooke Astor, James Farmer, and Dr. Robert Coles. Each of us had a military aide to escort us to the podium when our name was called. When it was my turn, President Clinton introduced me with these words:

In 1976, the Girl Scouts of America, one of our country's greatest institutions, was near collapse. Frances Hesselbein, a former volunteer from Johnstown, Pennsylvania, led them back, both in numbers and in spirit. She achieved not only the greatest diversity in the group's long history, but also its greatest cohesion, and in so doing, made a model for us all.

In her current role as the President of the Peter Drucker Foundation for Nonprofit Management, she has shared her remarkable recipe for inclusion and excellence with countless organizations whose bottom line is measured not in dollars, but in changed lives.

Since Mrs. Hesselbein forbids the use of hierarchical words like “up” and “down” when she's around, I will call this pioneer for women, volunteerism, diversity and opportunity not up, but forward, to be recognized.

As I walked toward the president, I thought of my family and all the experiences I had had in the mountains of western Pennsylvania that helped shape my life, that determined the person I would be and the leader I would become.

My leadership journey started a long time before that moment at the White House, in the small town of Johnstown in the Allegheny Mountains of western Pennsylvania, known for the famous Johnstown flood of 1889. In my early teens, in the formative years before I would play all kinds of leadership roles in national and international organizations, I never thought of myself as a leader. I was never a class president, student government officer, or the editor of the school paper—never the leader. I had a different focus. I was very sure I would be writing poetry for the rest of my life. I had books everywhere; a quiet studious life lay ahead for me. Leading and managing were the furthest things from my mind.

But as I look back, everything I learned in Johnstown prepared me for my life in leadership. The rich diversity of the Johnstown schools prepared a child like me to grow up, go anywhere in the world, and feel that that was where I belonged at that moment.

My leadership journey began long ago with a decision I made when I was seventeen years old.

The Beginning of My Journey

I was a freshman at the University of Pittsburgh's Junior College, which had recently been established on two floors of a beautiful Johnstown High School building—one of the earliest community colleges in the country. I was hungry for the learning my young professors would provide in an innovative junior college. Writing poetry had been my junior high school dream; in high school my focus shifted to writing for the theatre. At the junior college I developed my passion for writing. My mind was opening to all sorts of new adventures. My body, too. Something at Pitt unleashed an interest in sports. At five-foot-two, I even became a member of the women's basketball team, all of whom were six to ten inches taller than I was. (They were hard up that year.)

“Junior Pitt” was the perfect preface to the lifetime of learning I would pursue. I loved every minute. And then it came to an abrupt end.

Six weeks after the beginning of college, my father died from the results of malaria and intermittent fever he suffered while serving with the U.S. Army in Panama and the Philippines. When he was stricken with heart and lung failure, he tried to get support for his terrible illness from the Veterans Administration, but they rejected his plea, declaring his condition “Not Service Related.”

Despite this rejection, he loved his Army and his country to his last breath. As he lay dying in the hospital, he looked at me and said, “I wish they could see the old soldier, now.” I was stroking his cheek. (My mother was out in the hall, unable to face the ending.) As I kissed his forehead in those last minutes, I said, “Daddy, don't worry about Mother and the kids. I'll take care of the family.” A tear rolled down my father's cheek. I kissed it and he was gone.

We buried my father on a sunny October day and came back from the cemetery to my grandfather's house. We were sitting in the same beautiful music room where my father's body had been lying during the funeral service only a few hours ago. We sat in a small circle, my mother, sister, brother, Mama Wicks and Papa Wicks (our grandparents), Aunt Carrie and Uncle Mike, and Aunt Frances and Uncle Walter from Philadelphia. There had been many embraces and tears, of course, and then the conversation. Aunt Frances, in her most gentle, loving way said, “Frances, we want you to come to Philadelphia when this semester is over, live with us, and attend Swarthmore College. Your uncle and I will take care of everything, your tuition, books, whatever you need. We want you to finish college.” Philadelphia was a long way across the state from my hometown.

Then my grandfather, Papa Wicks, said, “Sadie and I want your mother and Trudy and John to come to live with us while you are in school. We have this big house, five bedrooms, and no one here but Mama and me. It would be the greatest joy for us to have your mother and brother and sister live with us while you finish college.” I looked at my mother, who had lived in that house when she was one of seven children. Grief stricken, my mother remained silent. The conversation was directed at me. At seventeen, I was asked to make a decision that would affect our lives forever, as I realized later.

I looked at the sun shining through the stained-glass windows I had loved as a child, and tried to imagine life without my father, what would happen without him. I thought of my promise to him as he lay dying. I said, “I think my father would want us to stay together. I'll finish this semester, and in January find a job and take college classes at night.” And I went on to describe the future with such feeling that my whole family supported me. There were tears. My Philadelphia aunt and uncle were disappointed but loving in their acceptance of my decision, as were my grandparents. No one argued. They loved and respected this seventeen-year-old who was called to keep a small family together.

We were driven back to Johnstown, and my mother; sister, Trudy, thirteen; brother, John, eleven; and I began life without the father we loved so dearly. I continued my Pitt classes eager for each day, aware that this was my last full-time semester.

Two young professors and their wives were wonderfully supportive. The professors, Dr. Doren Tharp (English) and Dr. Nathan Shappee (History), watched over me, even arranged for me to “audit” some graduate evening courses. Taking a few classes, auditing others, and reading and writing—the adventure in learning was measured not by credits but by substance. This was a rich, generous learning experience that would serve me well on the path ahead. Even after earning many credits and taking ever more classes, I never did get a formal degree, but I had begun a lifelong journey of learning that continues to be a joy to this day.

When the semester ended, I went to apply for a job wearing my best suit, high heels, and my mother's pretty wide-brimmed hat, with my long pageboy hair in a bun. I was interviewed by Mr. Corbin, the vice president of marketing and advertising at the Penn Traffic Company (a great department store, and part of the city's cultural center), who didn't realize I was only eighteen. (He didn't ask my age.) I worked as his assistant in advertising and marketing and then as the decorating consultant helping people design their interiors in the store's new model home. One day, Mr. Corbin asked me about some flowers on my desk, and I replied that it was my nineteenth birthday. He was shocked and said, “You're nothing but a god damn baby.” But he kept me on. I stayed until I married John Hesselbein three years later.

Learn by Doing

Don't ask what training I had to prepare me for the work I did. Much of my learning in those early years and later took place while doing. I did what I needed to do, what I was called to do, and had a successful early career until I married John Hesselbein, and another great adventure began.

As a young adult and mother of an eight-year-old son, I received my early management training as a Girl Scout troop leader. Later I became the chairman of the United Way in Johnstown. These experiences taught me lessons in mobilizing diverse people and groups together around mission and vision to achieve a common goal, and demonstrated the power of finding common ground. Living in a community that had not always appreciated its rich diversity, I knew I had to be courageous and fight for inclusion, equal opportunity, and equal access for all. I could not have learned any of this in a classroom.

In 1976, in New York City, I was offered the position of National Executive Director (CEO) of the Girl Scouts of the USA. I loved every one of my five thousand days, thirteen years as the executive director of the largest organization for girls and women in the world.

To this day, I carry with me the lessons I've learned on this long journey, whether I learned them at my grandmother's knee, in a dialogue with students on a college campus, with a roomful of executives from great corporations, or in a country far across the world. In June 2009, I spoke to Drucker Society gatherings in Korea, the sixty-eighth country in which I have spoken or represented my country. Every global encounter is a rich learning experience, one that is much more than an exposure to the culture, the arts, the history, or the current political situation. Such experiences are about the hearts and minds and friendships that make us who we are and bind us together in the human family.

It was a long way from my grandfather's music room to that day in the White House with President Clinton, yet a lifetime of learning took place from the day when the funeral was over, and a young girl began a journey—an adventure in learning that would accompany me wherever I would go.

When I made my decision to keep the family together, not to go to Swarthmore, it was all about purpose, as I would recognize later. My purpose was to keep my family together, as my father would have wanted me to do.

I did not aspire to be a leader, or seek out opportunities to lead. Doors opened. When I look at my journey—the many doors that were opened for me and the doors I opened myself—I have to ask, Who am I that people open doors for me? How have I been able to open doors for others? It is hard to distill the qualities needed in response to Emerson's “Be ye an opener of doors.” In who I am, I work hard to live by my values every day: respect, love, inclusion, listening, and sharing.

Perhaps in this chronicle I can explain why sharing my adventure in leadership begins with the person I have become, with who I am, and why the journey continues on. I have many questions to explore: What are the lessons learned? Rarely do we travel alone, so who are our fellow travelers? Did we choose them, or did they just appear? When do we say welcome; when do we say good-bye? Are there a few principles that guide us? What are the stops along the way? And when do we make the great discovery that leadership is a journey, not a destination?

Part One

Roots

Chapter 1

Stories of Family, Lessons of Love

Whenever I hear that someone is a “self-made” man or woman, I smile. None of us is truly self-made. We all stand on the shoulders of those who have gone before us, and we all have reason to be grateful for the help we have received along the way.

In my own life, I have many reasons to be grateful. I remember a Girl Scout message from an earlier day, “Honor the past. Cherish the future.” Both are equally important. If we do not honor the past, we may well end up thinking everything begins and ends with us. Such self-centeredness leads to swollen egos—and pride, which, as we all know, goeth before the fall.

Lessons of Love and Family

In my lifetime, with all the remarkable guides, family, and friends who made it all possible, there is one person who has had the greatest influence on my life and my work—my grandmother Sadie Pringle Wicks. This surprises people, for some of the greatest thought leaders in many fields have shared my journey in generous and highly visible ways. Yet from the time I could walk and talk and say, “Mama Wicks,” she had the greatest impact on me—personally, with my family, and professionally. She was small, gentle, loving, and quiet. She was always there for me. Her wisdom, her depth, and her love began to shape me from my earliest years. When I would walk in the room, I was the only person there. When she talked to me, I still remember, she would look into my eyes intently. For that moment she made me feel like the most important person in the world.

When I was a small child, she used to tell me family stories about our ancestors. For example, when Lincoln called for volunteers, the seven Pringle brothers, one of whom was Mama Wicks's father and my great-grandfather, set out with their father on the Pennsylvania Railroad train from Summerhill to Johnstown, nine miles away. First, the father walked with them to a photography studio, where he had each son photographed. Then they walked over to the post office, where they volunteered, and then the seven sons left for Pittsburgh to be inducted. The youngest was nineteen, the eldest twenty-seven. Six of these men were married, and left their wives and children and farms because their country called. It never occurred to them that three could go and four could stay at home and take care of their farms and their small lumber mill that made barrel staves way back in the mountains. All seven brothers volunteered. They were called to do what they did. At the end of the war, six brothers came home. The nineteen-year-old, the baby of the family, was fatally injured in the Battle of the Wilderness. One solider brother was given leave to bring Martin's body home. As a little girl, I would go with Mama Wicks to the Pringle Hill cemetery, our family burial ground, and we would pause at each weathered marble headstone as she told me stories about the seven Pringle brothers. With these visits and the stories, my grandmother showed me how to honor the past and the leaders in my family.

I experienced another example of my grandmother's influence not long after I was married and World War II began. My husband John volunteered for the Navy and was sent to Pensacola for training as a Naval Combat Air Crew photographer. It seemed a strange assignment for a young newspaper editor and writer, but off he went, saying good-bye to our eighteen-month-old Johnny and me.

I was determined to join him with the baby in Pensacola, but my mother, other family, and friends were horrified. Mother even suggested my leaving the baby with her and going alone. They had an extensive list of objections and excuses. It was a long train ride to Pensacola, he could be sent out as we arrived, and on and on. When in doubt, my practice was to ask Mama Wicks. She was the mother of nine children, with seven surviving, and had lived a long life with an adoring husband (so adoring that he wrote a long, passionate poem to her on their fiftieth wedding anniversary).

She listened to my story, put her arms around me, and said quietly, “Your place is with your husband and with the baby.” I went back home and said, “Mama Wicks says my place is with my husband.” No one could contradict Mama Wicks.

So, by Pennsylvania Railroad, from Johnstown, Pennsylvania, to Pensacola, Florida, with my eighteen-month-old baby, John, and his crib so he would feel at home, I traveled to be with big John. Later, after this trip, we took an even longer train ride from Pensacola to San Diego Naval Air Base to be with John. Those few years in naval towns, with very little money, were some of the best years of our lives. I took little Johnny to the beach while his father was flying; I'd say prayers and sometimes smile while thinking that a guy who had never even shot a BB gun was in a clear bubble under the plane with a camera and a big gun. John was told, “You shoot your way in, and shoot pictures on the way out. And as you are leaning out to shoot pictures, if you drop the camera, just follow it.” Navy training humor.

The war ended as John was finally to be deployed. Johnny and I came home to Johnstown by train in time for Christmas. The eighteen-month-old baby was now four years old. John didn't get discharged until February, and came home to find the Christmas tree still up, losing needles, yet with lights, ornaments, and gifts under the tree to welcome our sailor home.

Mama Wicks died before our tour of duty was over. Her simple statement, “Your place is with your husband,” taught me lessons about the power of love and about families belonging together. What a different life it would have been if I had heeded the timid ones who told me it was too dangerous to take the baby thousands of miles by train. Later, when I was called to give advice in many difficult situations, I learned to consider the issue and simply state from the heart my best advice, and it is always about them, not you. My grandmother taught me this.

The second-greatest influence on my life was Mama Wicks's daughter Carrie—my beloved Aunt Carrie who had a greater influence on my work and who I am today than my own mother.

Here in its entirety is the letter she sent to me on my birthday in 1985, which shows that the admiration was mutual.

Easton, PA

Dearest Frances:

The enclosed photograph of you, Mom and Pop will tell you how long you and I have been “Travel Companions”. [The photograph was of my grandparents with me as a six- or seven-year-old.] This was the last time you came with anyone. From that time on you came alone, or, with me when I had been visiting in South Fork.

I have such happy memories of those days. When you were four or five years old, I asked your opinions of so many things, such as, which dress I should wear to a party etc., and that has gone on through the years; of course you came to me for counsel. Well all in all, we have been good “Buddies.” Do you remember the time you came to Easton from New York in a blizzard after you had attended a National Board Meeting? You had to come in a bus via Reading, Pa.

You always went the second mile for Mike and me.

I knew, from the time you were five years old (in kindergarten) that you were destined to do great things and that Prophecy has come true. I do love you and hope all your wishes will be granted.

“He who would do wonderful things very often must travel alone.”

Henry Van Dyke

A happy, happy Birthday and dearest love to you.

Carrie

October 28, 1985

My husband appreciated Aunt Carrie almost as much as I did, and we loved including her in our travels. We smiled together during a trip to Paris when, in her late eighties, she sprinted up the long stairs to the top of the Basilica of the Sacre-Coeur, even though an electric lift was available. While in the United Kingdom, we also noticed that no one was more absorbed, more appreciative of the King's Library in the British Museum than Carrie.

Carrie's father was born in Tywardreath, a tiny village in Cornwall, England, a village of farmers, fishermen, and tin miners, who heard long ago the message of John Wesley and built a little Methodist chapel outside the village walls in the late 1700s. The great landowners would not permit “the dissidents” to build the chapel within the village walls at that time.

However, by 1823, this sturdy little band had grown so strong and so determined that they persuaded a farmer in the village to let them build their Methodist chapel on his land within the village walls. He agreed on one condition: on one side of the church wall, there had to be a lean-to for his cows. So for years, there were no windows on one side of the church.

Tausende von E-Books und Hörbücher

Ihre Zahl wächst ständig und Sie haben eine Fixpreisgarantie.

Sie haben über uns geschrieben: