Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: ONE

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

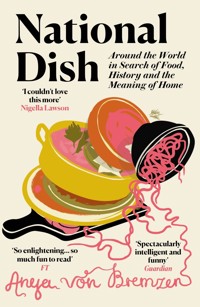

AN ENTERTAINING AND STYLISH EXPLORATION OF FOOD AND NATIONALITY, FROM AWARD-WINNING WRITER ANYA VON BREMZEN 'This voyage into culinary myth-making is essential reading... I couldn't love it more!' Nigella Lawson 'A truly captivating and evocative book. National Dish takes you on a food journey written with real warmth, wit and perception' Dan Saladino 'A sparklingly intelligent examination of, and a meditation on, the interplay of cooking and identity' Spectator ________ In National Dish, award-winning food writer Anya von Bremzen sets out to investigate the eternal cliché that "we are what we eat". Her journey takes her from Paris to Tokyo, from Seville, Oaxaca and Naples to Istanbul. She probes the decline of France's pot-au-feu in the age of globalisation, the stratospheric rise of ramen, the legend of pizza, the postcolonial paradoxes of Mexico's mole, the community essence of tapas, and the complex legacy of multiculturalism in a meze feast. Finally she returns to her home in Queens, New York, for a bowl of Ukrainian borscht -a dish which has never felt more loaded, or more precious. As each nation's social and political identity is explored, so too is its palate. Rich in research, colourful? characters and lively wit, National Dish peels back the layers of myth and misunderstanding around world cuisines, reassessing the pivotal role of food in our cultural heritage and identity. Featuring an epilogue on Ukrainian borscht, recently granted World Heritage status by UNESCO ________ FURTHER PRAISE FOR NATIONAL DISH 'So enlightening - as well as well so much fun to read... Von Bremzen is a superb describer of flavours and textures' Bee Wilson Financial Times A fast-paced, entertaining travelogue, peppered with compact history lessons that reveal the surprising ways dishes become iconic' New York Times 'Enchanting, fascinating, thought provoking and humorous' Claudia Roden 'A playful, erudite and mouthwatering exploration of ideas around food and identity. With the help of a diverse group of characters and dishes, Anya von Bremzen highlights the intricacies and contradictions of our relationship with what we eat' Fuschia Dunlop 'Anya von Bremzen's new book reads like an engrossing unputdownable novel about the perpetual soup of humanity' Oli Hercules 'An evocative, gorgeously layered exercise in place-making and cultural exploration...'Boston Globe 'Von Bremzen's knowledge is staggering and her writing witty, urgent and personal. I couldn't put it down' Diana Henry

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 481

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

‘A funny and astute exploration of the truth behind so-called national dishes’

Spectator’sBooksoftheYear

‘A fast-paced, entertaining travelogue, peppered with compact history lessons that reveal the surprising ways dishes become iconic’

New York Times

‘Von Bremzen’s writing is rich, urgent and redolent of her literary heritage… A book that deserves to be devoured’

Irish Times

‘A playful, erudite and mouthwatering exploration of ideas around food and identity’

Fuchsia Dunlop

‘Witty, urgent and personal. I couldn’t put it down’

Diana Henry

‘Whether she’s decoding pizza in Naples or tortillas in Mexico, Anya is your perfect guide to the profound subjects of nationalism, food, and identity. And she’s often funny as hell’

René Redzepi

‘A meditation on the paradox of national identity that will seduce the gastronomic curiosity of any world traveler’

Lawrence Osborne

ii

iii

v

For Larisa and Barry And in memory of my brother, Andreivi

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Paris: Pot on the Fire

On a gray fall morning in the days sometime before the pandemic, my partner Barry and I arrived in Paris, where I planned to make a pot-au-feu recipe from a nineteenth-century French cookbook. It was for a book project of my own, one that had begun to bubble and form in my mind, about national food cultures told through their symbolic dishes and meals, which I would cook, eat, and investigate in different parts of the world.

Dumping our luggage in our apartment swap in the multicultural 13th arrondissement, we immediately rushed across the wide Avenue d’Italie—to begin sabotaging French national food culture by ingesting a frenzy of calories. Non-Gallic calories.

At a petite dive called Mekong, a stupendous curried chicken banh mi was prepared with something like love by a tired Vietnamese woman who sighed that Saigon was très belle, mais Paris? Eh bien, un peau triste … At a halal Maghrebi boucherie there was mahjouba, a flaky Algerian crepe aromatic with a filling of stewed 2tomatoes and peppers. And a mustached butcher being tormented by a middle-aged Parisienne, prim and imperious. After she departed with her single veal escalope, he exhaled with a whistle and made a “crazy” sign with his finger.

Which pretty much summed up how I’d always felt about Paris.

Ever since my first visit back in the 1970s, as a sullen teenage refugee from the USSR newly settled in Philadelphia, my relationship with the City of Light had always been anxious and fraught. Other people might swoon over the bistros, rhapsodize about first encounters with platters of oysters and crocks of terrine. Me, I saw nothing but despotic prix fixe menus, withering classism, and Haussmann’s relentless beige facades—assembly-line Stalinism epauletted with window geraniums.

But right now, onward, for pink mochi balls at a Korean épicerie on the main Asian artery, Avenue de Choisy, after which I frantically stuffed our shopping bag with frozen Cambodian dumplings and three huge Chinese moon cakes at the giant Asian supermarket, Tang Frères. Just nearby, at a fluorescent-lit Taiwanese bubble tea parlor, was where I discovered the Vietnamese summer roll–sushi mashup. Behold the sushiburrito.

It was the happiest Paris arrival I’d ever had. The 13th arrondissement comforted me right back to where I’d just left, my buoyant polyglot New York neighborhood of Jackson Heights, Queens. The postcolonial profusion of lemongrass, fish sauce, and harissa helped soften my Francophobic unease.

Sending Barry off to settle into our apartment swap—whose tiny cramped kitchen, by some astounding kismet, featured a large poster of Frederick Wiseman’s documentary In Jackson Heights—I carried 3my purchases to our petite neighborhood park. South Asian and North African kids were kicking a soccer ball by the hibiscus bushes. On a bench, a Koranic old man with a wispy beard and a skullcap put his hand to his heart to greet me: “As-salaam alaikum!”

With this blessing and a test bite of moon cake (funky salted egg filling), I pondered that which had brought me to Paris—a place unbeloved by me, but historically crucial to the concept of a national food culture. My journey could hardly start anywhere else.

NATIONAL CUISINES, one food studies scholar observes, suffer from “problematic obviousness.” The same could be said for the very idea of “national.” Most of us take a view of nations as organic communities that have shared blood ties, race, language, culture, and diet since time immemorial. Among social scientists, however, this “primordialism” doesn’t hold water. Scholars from the influential mid-1980s “modernist” school (Ernest Gellner, Eric Hobsbawm, Benedict Anderson) have persuasively argued that nations and nationalism are historically recent phenomena, dating roughly to the late Enlightenment—and to the French Revolution in particular, which supplied the model for our contemporary concept of the nation, as France’s absolutist monarchy of divergent peoples and customs and dialects was transformed into a sovereign entity of common laws, a unified language, and a written constitution, ruled in the name of equal citizens under that grand idealist banner: Liberté, égalité, fraternité!

Inspired by the French example, the long nineteenth century would see the rise of ethnonational self-determination from colonial empires, until the first and second world wars released flood tides of 4new nation-states from the ruins—some of their current borders, of course, blatant carve-ups by European colonial powers.

The final wave of nations arrived in the early 1990s with the dissolution of Yugoslavia and the USSR. It was in the latter where I was born in the sixties, to be raised on the imperialist scarlet-blazed myth of the fraternity of Soviet socialist republics—as diverse as Nordic Estonia and desert Turkmenistan—all wisely governed by Moscow, my hometown. The food we relished was the disparate cuisine of an empire: Uzbek pilaf, spicy Georgian chicken in walnut sauce, briny Armenian dolmas; they relieved the quotidian blandness of Soviet-issue sosiski (franks) and mayonnaise-laden salads.

Then in 1974 my mother and I became stateless refugees, emigrants to the US.

I still remember my ESL teacher lecturing grandly in a loud, nasal Philadelphia accent about how proud we students should feel being part of a glorious melting-pot nation. And me trying to imagine myself somehow as a slice of weird Day-Glo–orange Velveeta melting away in the cauldron of gloppy chili of our school lunches. Instinctively wary of the great American assimilationist model, I didn’t melt in very well. My overbearing patriotic Soviet education made me cynical about states and their identities.

Though now I sometimes wonder how it would feel to belong to a small, close-knit nation—Iceland?—I feel most at home in my Jackson Heights barrio of 168 languages, where I can have Colombian arepas for breakfast and Tibetan momos for lunch, and nobody cares about my identity. I’m a Jewish-Russian American national, born in a despotic imperium long deleted from maps. I speak with a heavy accent in several languages, lead a professionally nomadic existence as a food and travel writer, and own an apartment in Istanbul, former seat of the multiethnic Ottoman 5empire. At table my mom, Barry, and I are passionate ecumenical culturalists. We make gefilte fish for Passover, Persian pilaf for Nowruz, and a ham for Russian Orthodox Easter. The Polish philosopher Zygmunt Bauman has a great phrase for this very common postmodern—globalized—condition, of not committing to a single identity or place or community:

“Liquid modernity,” he calls it. A life where “there are no permanent bonds.”

So why then would someone like me set out to explore national food cultures?

Because with the rise and domination of globalization, nations and nationalism somehow seem both more obsolete and more vital and relevant than ever. There’s hardly a better prism through which to see this than food. From Kampala to Kathmandu we confront the same omnipresent fast-food burger, while from Tbilisi to Tel Aviv the same “global Brooklyn” community of woolly hipsters protests such corporate/culinary imperialism with craft beer and Instagrammable sourdough loaves. In a way, both the craft brews and the burgers are different political flavors of transnational food flows. Such full-flood globalization, you’d think, would have wiped away local and national cravings. But no: the global and local nourish each other. Never have we been more cosmopolitan about what we eat—and yet never more essentialist, locavore, and particularist. As the world becomes ever more liquid, we argue about culinary appropriation and cultural ownership, seeking anchor and comfort in the mantras of authenticity, terroir, heritage. We have a compulsion to tie food to place, to forage for the genius loci on our pilgrimages to the birthplace of ramen, the cradle of pizza, the bouillabaisse 6bastion. Which is what I’ve been doing myself professionally for the last several decades.

What’s more, as a national symbol, food carries the emotional charge of a flag and an anthem, those “invented traditions” crucial to building and sustaining a nation, to claiming deep historical roots. While in fact, often, they are both manufactured and recent.

And so here I sat on a bench in Paris, unwrapping my hyper-globalized sushiburrito while contemplating a super-essentialist quote from the great scholar Pascal Ory. France, wrote Ory, “is not a country with an ordinary relation to food. In the national vulgate food is one of the distinctive ingredients, if not the distinctive ingredient, of French identity.”

Italians, Koreans, even Abkhazians would certainly wax indignant that their relation to food is every bit as special. But if our identities, at their most primal, involve how we talk about ourselves around a dinner table, it was France—and Paris specifically—that created the first explicitly national discourse about food, esteeming its cuisine as an exportable, uniquely French cultural product along with terms such as “chef” and “gastronomy.” It was France that in the mid-seventeenth century laid the foundation as well for a truly modern cuisine, one that emerged from a jumble of medieval spices to invent and record sauces and techniques the world still utilizes today. To create “restaurants” as we know them, and turn “terroir” into a powerful national marketing tool.

Of course (to my not-so-secret glee, I admit) this Gallic culinary exceptionalism had taken a terrific beating over the past couple decades. So where was it now? And where, and how, did the idea of France as a “culinary country” come to be born? 7

The pot-au-feu that was to occupy me in Paris, my symbolic French national meal, came from a book by a deeply influential nineteenth-century chef whose fantastical story befits an epic novel. Abandoned on a Parisian street by his destitute father during Robespierre’s terror, Marie-Antoine Carême would have been invented—by Balzac? Dumas père? both were gourmandizing fans—if he didn’t already exist. Self-made and charismatic, he rose to become the world’s first international celebrity toque (in fact he invented the headgear). Not only was Carême the grand maestro of la grande cuisine’s architectural spun-sugar spectaculars, he also codified the four mother sauces from which flowed the infinite “petites sauces,” sauce being so essential to the French self-definition. And cheffing for royalty and the G7 set of his day, he spread the supremacy of Gallic cuisine across the globe. Or to put a modern spin on it, Carême conducted gastrodiplomacy (our au courant term for the political soft power of food) on behalf of Brand France.

Even more influential was Carême’s written chauvinism. “Oh France, my beautiful homeland,” he apostrophized in his 1833 seminal opus, L’Art de la Cuisine Française au Dix-Neuvième Siècle, “you alone unite in your breast the delights of gastronomy.”

How then are national cuisines and food cultures created? The answer, as I’d come to learn, is rarely straightforward, but a seminal cookbook is always a good place to begin. And as the influential scholar of French history Priscilla Ferguson observed, it was Carême’s books that unified La France around its cuisine and food language, at a time when French printed texts had begun making the ancien régime’s aristocratic gastronomy accessible to an eager, more inclusive 8bourgeois public. “Carême’s French cuisine,” Ferguson writes, “became a key building block in the vast project of constructing a nation out of a divided country.”

As the Chef of Kings addressed his public: “My book is not written for the great houses. Instead … I want that in our beautiful France, every citizen can eat succulent meals.”

And the succulence that kicks off his magnum opus is the pot-au-feu, “pot on the fire.” Broth, beef, and vegetables, soup and main course all in one cauldron, it’s a symbolic bowlful of égalité-fraternité that Carême anointed un plat proprement national, a truly national dish. Pot-au-feu carries a monumental weight in French culture. Voltaire affiliates it with good manners; Balzac and even Michel Houellebecq, that scabrous provocateur, lovingly invoke its bourgeois comforts; scholars rate it a “mythical center of family gatherings.” Myself, I was particularly intrigued by its liquid component, the stock or bouillon/broth—the aromatic foundation of the entire French sauce and potage edifice.

“Stock,” proclaimed Carême’s successor, Auguste Escoffier, dictator of belle epoque haughty splendor, “is everything in cooking, at least in French cooking.”

Stock was homey yet at the same time existentially Cartesian: I make bouillon, therefore I cook à la française.

“CARÊME … POT-AU-FEU … such important subjects.” Bénédict Beaugé, the great French gastronomic historian, saluted my project. “And these days, alas, so often ignored.”

In his seventies, his nobly benevolent face ghostly pale under thinning white hair, Bénédict radiated a deep, humble humanity—the 9opposite of a blustery French intellectual. His book-lined apartment lay fairly near the Eiffel Tower, in Paris’s west. Walking up his bland street, Rue de Lourmel, I noted a Middle Eastern self-service, a Japanese spot, and a wannabe hipster bar called Plan B.

“Ah, the new global Paris,” I remarked, to open our conversation.

“And a chaos, culinarily speaking,” Bénédict said. “A confusion—reflecting a larger one about our identity—lasting now for almost two decades … Though a constructive chaos, perhaps?”

He wondered, however, as I’d been wondering, about the “overarching idea of Frenchness, of a great civilization at table.” In Paris nowadays, he said, only Japanese chefs seemed fascinated with Frenchness, while Tunisian bakers were winning the Best Baguette competitions.

“Yes, immigrant cuisines are changing Paris for the good,” he affirmed. “But the problem? In France, we don’t have your American clarity about being a melting-pot nation.”

Indeed. Asking journalist friends about the ethnic composition of Paris, I’d been sternly reminded that French law prohibits official data on ethnicity, race, or religion—effectively rendering immigrant communities like the ones in our treizième mute and invisible. All in the name of republican ideals of color-blind universalism.

“Ah, but pot-au-feu!” Bénédict nodded approvingly. “That wonderful, curious thing, a dish entirely archetypal—meat in broth!—and yet totally national!”

As for Carême? He smiled tenderly as if talking about a beloved old uncle. “An artiste, our kitchen’s first intellectual, a Cartesian spirit who gave French cuisine its logical foundation, a grammar. However …” A finger was raised. “The rationalization and ensuing 10nationalization of French cuisine—it didn’t exactly begin with Carême!”

“Ah, you mean La Varenne,” I replied.

In 1651, François Pierre de La Varenne, a “squire of cooking” to the Burgundian Marquis d’Uxelles, published his Le Cuisinier François, the first original cookbook in France after almost a century dominated by adaptations of Italian Renaissance texts—and the first anywhere to use a national title.

Hard to imagine, but until the 1650s there really wasn’t anything remotely like distinct, codified “national” cooking, anywhere. While the poor subsisted on gruels and weeds (so undesirable then but now celebrated as “heritage”), the cosmopolitan cuisine of different courts brought in delectables from afar to show off power and wealth. All across Europe, cookbooks were shamelessly plagiarized, so that European (even Islamic) elites banqueted on pretty much the same roasted peacocks and herons, mammoth pies (sometimes containing live rabbits), and omnipresent blancmanges, those Islamic-influenced sludges of rice, chicken, and almond milk. Teeth-destroying Renaissance recipes often added two pounds of sugar for one pound of meat, while overloads of imported cinnamon, cloves, pepper, and saffron made everything taste, one historian quips, like bad Indian food.

Le Cuisinier François offers the earliest record of a seismic change in European cuisine. Seasonings in La Varenne’s tome mostly ditch heavy East India spices for such aromates français as shallots and herbs; sugar is banished to meal’s end; smooth emulsified-butter-based sauces begin to replace the chunky sweet-sour medieval concoctions. Le Cuisinier brims with dainty ragouts, 11light salads, and such recognizable French standards as boeuf à la mode. One of La Varenne’s contemporaries best summed up this new goût naturel: “A cabbage soup should taste entirely of cabbage, a leek soup entirely of leeks.”

A modern mantra, first heard in mid-seventeenth-century France.

“Then following La Varenne, in the next century,” said Bénédict, a frail eminence among his great piles of books, “the Enlightenment spirit fully took over, while print culture exploded.” Fervent new scientific approaches teamed up with Rousseau’s cult of nature, whose rusticity was in fact very refined and expensive. Among other things, this alliance produced a vogue for super-condensed quasi-medicinal broths.

And the name of these Enlightenment elixirs?

Restaurants.

As historian Rebecca Spang writes in The Invention of the Restaurant, “centuries before a restaurant was a place to eat … a restaurant was a thing to eat, a restorative broth.” Restaurants as places—as attractions that would be exclusive to Paris well into the mid-nineteenth century—first appeared a couple of decades before the 1789 Revolution, in the form of chichi bouillon spas, where for the first time in Western history, diners could show up at any time of day, sit at their separate tables, and order from a menu with prices. By the 1820s Paris had around three thousand restaurants, and they already resembled our own. Temples of aestheticized gluttony, yes—of truffled poulet Marengo and chandeliered opulence. But also, crucially, social and cultural landmarks that inspired an innovative and singularly French genre of literary gastrophilosophizing—attracting Brit and American pilgrims who assumed, per Spang, that France’s “national character revealed itself in such dining rooms.” Which it did. 12

“Of course national cuisines don’t happen overnight,” cautioned Bénédict, as I made ready to leave him to his texts and histories. It was a long process that mirrored developments in culture and politics. But one uniquely French hallmark, he stressed, going back to the mid-1600s, was a culinary quest for originality and novelty, made even more insistent by the advent of restaurants and the birth of the food critic. And pretty much ever since La Varenne, each triumphant new generation of French cuisiniers has expressed a recommitment to the ideal of goût naturel, to a more inventive and scientific—and more expensive—refinement. Carême? He, too, professed the “vast superiority” of his cuisine on account of its “simplicity, elegance … sumptuousness.” Escoffier boasted of simplifying Carême—to be followed by an early-twentieth-century cuisine-bourgeoise regionalist movement that ridiculed Escoffier’s pompous complexities. Then the 1970s nouvelle cuisine rebels (Bocuse, Troisgros, and the like) attacked the whole Carême-Escoffier legacy of “terrible brown sauces and white sauces” to raise the conquering flag of their own (shockingly expensive) lightness and naturalness.

But why—why, after the nouvelle cuisine revolution, did this uniquely French narrative of reinvention and rationalization flounder and tank spectacularly?

“FERRAN.”

Nicolas Chatenier pronounced the culprit’s name with a somber flourish. Nattily dressed, a handsome fortyish businessman-boulevardier, Nicolas was, at the time, the French Academy chair for the enormously influential San Pellegrino 50 Best Restaurants, Michelin’s archrival. 13

He meant Ferran Adrià, the avant-garde Catalan genius of the erstwhile El Bulli restaurant on Spain’s Costa Brava. In the late twentieth century Adrià appeared seemingly out of thin air, a magician cum scientist who, just like that, brilliantly and wittily challenged, deconstructed, and reimagined established French culinary grammar and logic—the way Picasso and Salvador Dalí upended and electrified the world of art.

Nicolas and I were hashing over the apocalyptic toppling of the cuisine française edifice at a burnished haute-bistro called La Poule au Pot, which charged sixty bucks for a portion of pot-au-feu’s poultry cousin.

Nicolas grew up in a bourgeois Parisian family and remembers their festive excursions to France’s grand dining temples as utter enchantments. “That bonbonnière that was Robuchon’s Jamin …” he reminisced dreamily, as a bearded hipster garçon apportioned our yellow heritage Bresse chicken in broth with a cool millennial irony. “Those fairy-tale desserts chez Troisgros …” Maybe that’s why as an aspiring food journalist in the early aughts, he became so troubled by the raging French gastronomy crise. So he wrote a long magazine article laying out the facts. Which nobody wanted to hear. “People accused me,” he chuckled, “and I’m not making this up, of being a British spy!”

His eyes turned doleful. “France, a great food empire for centuries. Best training, best products, best chefs. And then …” He lifted a tragic hand. “The national humiliation of that New York Times Magazine story with Ferran on the cover about France declining and Spain ascending!”

“But come, Nicolas,” I chided, “that article was almost twenty years ago!”

“And people here still talk about it,” he assured me gravely. 14

It saddened him how the Spanish had displayed “amazing” unity around Ferran, while France’s contemporary generation, led by Joël Robuchon and Alain Ducasse, were fighting each other.

“It was different with the seventies nouvelle cuisine guys,” he insisted. “Troisgros, Bocuse, Michel Guérard, they were clever, authentic—united.”

Sure, theirs was a radical 1968 rhetoric; revolution was in the air. But they seized upon that moment, a moment that was part of a sweeping larger cultural energy. “Everything was nouvelle and innovative in France then. Nouvelle Vague cinema, nouveau roman literature, a new angle on cultural criticism. We were the capital of culture and fashion—Godard, Truffaut, Yves Saint Laurent!”

He paused for a mournful slurp of chicken bouillon. “Followed by twelve years of stagnant immobility under Chirac. A slow, boring [sigh] … decline.”

So the culinary crisis wasn’t really because of Ferran?

Nicolas gave a Gallic shrug of assent. “It was a cascade of crises.”

Crises such as outmoded, unsustainable Michelin standards of luxury that bankrupted some chefs, drove others even to suicide; the thirty-five-hour work week introduced in 2000, plus a draconian 19.5 percent VAT (lowered since) that put a further impossible strain on restaurants; at lower-rung places, scandals that erupted about pre-prepared dishes and frozen ingredients; in the countryside, chain supermarket and factory farms that threatened local traditions. Plus the global fast-food invasion arrived.

“France, the exporter of a glorious civilization at table, became hooked on McMerde!” Nicolas lamented. “Even our baguettes became terrible. Prebaked, frozen, industrial.”

But now, apparently, now all was ending well. Baguettes were 15spectacular once more and millennials were crazy for organic and farm fresh, as if channeling Rousseau’s nature cult. The new vibe, in eastern Paris especially, brought Brooklynesque coffee bars, creative cocktails, Asian-influenced restaurants. “Currently all lines in Paris are blurred,” Nicolas declared, “and that’s really fun! Okay, we got thrown off for a while by the vitriol from abroad—but we have an open mind now! We may have lost the idea of a national cuisine, but we’ve opened up to outside. Go to Cheval d’Or,” he admonished, “this Japanese guy doing this supercool neo-Cantonese food …”

“So wait—you’re saying the Paris restaurant scene became interesting because chefs ditched the idea of Frenchness?”

Nicolas swallowed hard. He looked cornered. As the 50 Best head for France, he had to defend national values. “Well, yes, for a bit,” he allowed. “But now people are sentimental again—about bistros! The céleri rémoulade and poulet-au-pot we just had. Look around: every table is full, every night. At these prices.”

Terroir, he mused, poking his fork into the carcass of our poulet de Bresse, its graphic, scary claw still sticking out. Maybe that was always France’s answer, her true national narrative. France’s incredible products … and how the French talk so superbly about them, feeding the global appetite that they effectively created.

After dinner I wandered along the moonlit Seine, ignoring that romantic riverside Francophiles swoon over so tiresomely, to ponder my conversation with Nicolas. Priscilla Ferguson argues that French cuisine reigned supreme because of the food itself—the proof in the pudding. But, as Nicolas contended, also because the French were such aces at discourse: their conversation, their writing and 16philosophizing, had elevated gastronomy from subsistence or even a show of class power to a cultural form on par with literature, architecture, and music.

But their conversation, it occurred to me, was what ultimately hurt French cuisine.

Because it became bogged down and essentialist. As progressive ideas erupted elsewhere—the new imaginative science in Spain, the focus on sustainability in California and Scandinavia—the French became fixated on the anxiety of losing their storied supremacy. Their narrative turned nostalgic, defensive, rigid with hauteur and heritage. I recalled a star-studded chef conference in São Paulo about a decade ago. The young Catalan pastry wiz Jordi Roca presented a magically levitating dessert. Brazilian chef Alex Atala passionately discoursed on Amazonian biodiversity. And the French? I still remember rolling my eyes along with the audience when a kitchen team of the gastronomic god Alain Ducasse came onstage to pompously lecture about the importance of … stocks. Which is like going on about fountain pens at an AI summit.

Yet here I was in Paris myself, knee-deep in bouillon, researching pot-au-feu along with the history and science of stocks—fishing for broader connections between cuisine and country. It amazed me, for instance, how an eighteenth-century cup of restorative broth sat so smack at the French Enlightenment’s intersection of cuisine, medicine, chemistry, emerging consumerism, and debates about taste, ancienne versus nouvelle. While a century later, broth represented democratization of dining, as inexpensive canteens called bouillons—the world’s proto–fast-food chains—sprang up in fin de 17siècle Paris, serving beef in broth plus a few simple items to disparate classes in hygienic, gaily attractive surroundings.

Now in the living room of our apartment with its clutter of Balzacian bric-a-brac, I reexamined once again Carême’s opening recipe in L’Art de la Cuisine Française: “pot-au-feu maison.”

Put in an earthenware marmite four pounds of beef, a good shank of veal, a chicken half-roasted on a spit, and three liters of water. Later add two carrots, a turnip, leeks, and a clove stuck into an onion …

A straightforward recipe, if a little weird. Why the half-roasted chicken?

What made the recipe a landmark, Bénédict told me, was Carême’s Analyse du pot-au-feu bourgeois, his opening preamble. For here was the Chef of Kings, who’d dedicated his pages to Baroness Rothschild, explaining the science and merits of bouillon for a bourgeois female cook—bridging the gap between genders and classes, praising his reader as “the woman who looks after the nutritional pot, and without the slightest notion of chemistry … has simply learned from her mother how to care for the pot-au-feu.” This preamble, according to scholars, was what truly nationalized the dish, leading generations of writers and cooks to start their own books with this one-pot essential.

But how else, I asked myself, and for what other reasons, do dishes get anointed as “national”?

There was unexpected economic success abroad (pizza in Italy); tourist appeal (moussaka in Greece); nourishing of the masses during hard times (ramen in postwar Japan). Even, sometimes, top-down 18fiat: see the strange case of pad Thai, a Chinese-origin noodle dish (like ramen) that got “Thaified” with tamarind and palm sugar and decreed the national street food by the 1930s dictator Phibun—part of his campaign that included renaming Siam as Thailand, banning minority languages, and pushing Chinese vendors off the streets.

Among all the contenders, of course, one-pot multi-ingredient stews made the most convincing national emblems with their miraculous symbolic power to feed rich and poor, transcend regional boundaries, unite historical pasts. In Brazil, feijoada was canonized for supposedly melding Indigenous, colonial, and African slave cultures in a cauldron of black beans and porkstuffs, while in Cuba the exact same thing was said about the multi-meat tuber stew, ajiaco. Or consider (if one must) the creepy Nazi promotion of Germany’s eintopf (“one-pot”) for forging some mythical völkisch community. Never mind that the word “eintopf” never even appeared in print until the 1930s. (A not-uncommon sort of situation, I would discover.)

And so here was my pot-au-feu with its very genuine historical roots. Although hardly a dish of the peasants (for whom meat was once a year) it was still easily mythologized as the perfect embodiment of French republican credos, a fraternal pot for toute la France. Even that towering snob Escoffier praised it as a “dish that despite its simplicity … comprises the entire dinner of the soldier and the laborer … the rich and the artisan.” By Escoffier’s belle epoque reign, France’s Third Republic ambition to aggressively nationalize its citizenry through universal education, military service, regional integration, and rural modernization was almost fulfilled. Although women remained second-class citizens—unable to vote until 1944—“teaching Marianne how to cook,” as one scholar 19puts it, “had become a national issue of paramount importance.” And pretty much every domestic science textbook for girls began with pot-au-feu, which was also the name of a popular late-nineteenth-century domestic advice magazine for bourgeois housewives. Why, pot-au-feu even perfectly illustrated the era’s embrace of regionalist “unity in diversity,” since every region in France had its version (garbure in Languedoc, kig ha farz in Brittany), all now celebrated as parts of a grand, savory national whole.

The more I thought about it, the more pot-au-feu seemed like an obvious master class in “national dish” building.

Except …

People I questioned talked about it in a perfunctory nostalgic past tense—ah, grand-mère, ah, Sunday pot-au-feu lunch back in the countryside—before breathlessly recommending a bao burger hotspot or a très Brooklyn mezcal bar. The two important chefs advertised to me as pot-au-feu experts were both on some extended Asian trips and, judging from their gleeful Instagram feeds, not planning to return anytime soon.

Even Alain Ducasse, that éminence grise of Gallic gastronomy, seemed to be shoving the exemplary “national dish” under the bus.

“Carême … pot-au-feu … hmm …” mused Ducasse, in response to my question, when I called on him at his flagship Hôtel Plaza Athénée restaurant.

Clad in an impeccable tan suit and his signature Alden high-top shoes, Ducasse, now in his sixties, with his glut of Michelin stars and a restaurant empire across several continents, loomed in my mind as a kind of modern corporate Carême. A grand cultural 20entrepreneur and gastrodiplomat who entertained heads of state at Versailles on behalf of Brand France.

“Pot-au-feu …” Ducasse shook his silver-maned head. Having converted to a Rousseauian-sounding cuisine de la naturalité—that evergreen Gallic recommitment—he was nowadays focused on the health of the planet. Red meat? he frowned. Bad for environment.

“Stocks, fonds, les sauces classiques françaises … Carême, Escoffier …” Ducasse summed up my questions distractedly. “Bien sûr, it’s our French DNA … they inspire us still.” Though he didn’t sound exactly passionate. “In our work we’ve kept”—he paused to calculate—“about ten percent. Maybe less.”

Ten percent?

I thought of that stage show in São Paulo, the hoary air of presumption of the eternal ultimacy of French stocks.

Then again, my friend Alexandra Michot, food editor of French Elle, had been much more ruthless a few days before. “It took us a full hundred years,” she sputtered, “to shake off the Carême-Escoffier legacy, to unlearn that overbearing French cuisine grammar. And now,” she proclaimed, “we’re finally free! And the future is beautiful.”

Which was more or less the substance of Ducasse’s line.

Ten years ago the French food scene was, Ducasse admitted tactfully, un peu depressed. But today? “Today there’s so much talent, so much diversity—Asian, North African, new interpretations of bistros. So many new stories all unique, individual, personal.”

This was verbatim what I’d been hearing from Nicolas and others and experiencing myself—but coming from Alain Ducasse, the establishment, it was, I guess, the new official French narrative: universalism is dead, long live particularism. And Gallic haute 21cuisine itself? Pretty dead, too—because some months after my visit, Ducasse would be evicted from his prestigious but unprofitable Plaza Athénée address and would collaborate on a pop-up with Albert Adrià, the kid brother of his historic archnemesis, Ferran. Last I heard he’d opened a high-end vegan burger stand.

SO WHERE did all this leave my Carême/pot-au-feu project—the logical starting point, or so I’d figured, for probing French food and identity—in this birthplace of Gallic gastronomy that no longer seemed interested?

Even my devoutly Francophile elderly mom, who’d just landed in Paris en route to New York from a visit to Moscow, was eyeing the underside of the proverbial bus.

“But Anyut …” she wondered, using my Russian diminutive on our way to the neighborhood butcher after a morning snacking on Tunisian “pirozhki” and Cambodian “blini.” “Why pot-au-feu? As the French national dish, shouldn’t we be making couscous or something?”

A description I’d just read, by an Algerian political activist, came to my mind: France was a “McDonald’s-couscous-steak-frites society.” Mondialization prevailed. Had I absurdly fallen into some tourist authenticity trap, expecting a cuisine frozen in amber? Was I being naïve, pursuing some hoary archival dish and its supposedly national narrative in the transcultural capital of a country whose grand official color-blindness was no longer able to whitewash its diversity?

And where, indeed, was pot-au-feu in surveys of les plats préférés des Français? 22

About a decade ago le couscous in fact topped the polls, provoking the usual chauvinist outcries and inevitable taunting headlines in Britain about “la France profonde choking on its soupe à l’oignon.” (Britain, please note, savvily replaced roast beef with chicken tikka masala as its own edible symbol to show off its multiculturalism.) The latest French results looked more calming for nationalists, with couscous ranked eighth and magret de canard (but how’s duck breast even a dish?) in first place. But still, these days France’s best-loved malbouffe (junk food) was a gooey, steroidal love child of burrito and shawarma known as “French tacos.”

THE ONLY PERSON in all of Paris, it seemed, truly enthusiastic about my pot-au-feu, besides the august Bénédict Beaugé, was Monsieur Larbi, the Moroccan butcher.

“Donc, alors, pot-au-feu, Madame Anya?” He was practically rubbing his hands in excitement when I came in with my mom, doggedly, to order the meats.

“Pot-au-feu, ooh-la-la, bravo!” approved Madame Fatima, a Berber regular buying two kilos of quivering sheep’s brains.

Monsieur Larbi ran the most convivial of the halal boucheries on Avenue d’Italie. It was a throbbing cumin-scented community center crowded with men in cheap leather jackets, girls in torn jeans, matrons in headscarves, all gossiping about the vagaries of Parisian life in French, Berber, and Arabic. Portly and gray haired, M. Larbi radiated a gruff joie de vivre. He’d been an engineer back in Essaouira, but here in Paris, who’d give him a decent job? “Paris,” he would lament, “where is its humanity? It’s cold, classist, unaffordable.” And naturally halal butchers were best. Because? “Because 23the French are too lazy to get up at dawn, and have lost any connection to animals.”

And, he’d hint darkly, halal issues brought out the worst of French xenophobia.

“Madame Anya, soon they’ll force us to eat jambon!” Monsieur Larbi would whisper.

But now he was all pot-au-feu. “Gite, paleron, plat de côtes.” He slapped the classic (and untranslatable) cuts of beef on the scale, then flourished two giant marrow bones and started sawing them in half.

“Mais pardon, Monsieur Larbi,” I bleated. “Pas de gites ou plat de côtes pour moi …” Instead I asked for Carême’s particular five pounds of tranche de boeuf (rump), a veal shank—and a half-roasted chicken.

M. Larbi looked surprised. Even mildly offended. His expertise, his participation in the civilizing mission of France, was being questioned. And by whom? By someone who mangled the phrase au revoir. “But, Madame Anya”—he shook his head gravely—“ceci n’est pas un vrais pot-au-feu. French cuisine, il y a des règles.” There are rules.

A chicken in a pot-au-feu? Jamais! pronounced Madame Fatima. Never!

On my phone, I showed M. Larbi Carême’s landmark recipe. He still looked unconvinced. My phone was passed around the store. Opinions were aired. Women in headscarves were giggling, rolling their eyes.

And suddenly I had an unsettling feeling of being the “other” in this shop full of immigrants, an uncivilized and unassimilated intruder, ignorant of France’s rules. Yes, belonging, identity, they could be liquid, too, contingent and transactional. Here were people 24who had bashed France only five minutes before now defending its patrimoine culinaire as their own, at least for a moment.

“What a strange scene,” said my mom as we headed home with the meats. “I can’t imagine Mr. Nacho, our Colombian butcher in Jackson Heights, lecturing on any American dishes.”

EVER ATTEMPTED A MONUMENT de la gastronomie française in a five-square-meter kitchen with no counter space as a sudden autumn heat wave kicks in, sending Parisians flocking to outdoor cafés for tequila cocktails and cooling Asian salads?

Oh, and I wasn’t just intending a modest little pot-au-feu family supper. No, mesdames et messieurs: for my project, and in honor of my mother’s presence, I’d decided on the whole grand shebang as a setting. The certified “gastronomic meal of the French.”

What’s that?

In 2010, when nation-branding with food was already lucrative business—as Peru, Thailand, Korea, Japan, and Mexico were all busily capitalizing on the soft power of their cuisines to promote tourism and exports—le repas gastronomique des Français was inscribed on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) list after years of intense lobbying by the Mission Française du Patrimoine et des Cultures Alimentaires. It was the first time that the ICH list—established in the early aughts to “decolonize heritage” but quickly appropriated by various state players for their own image-building agendas—had recognized foodways, along with the usual stuff, such as Peru’s Scissor Dance. (“Traditional Mexican Cuisine” got a nod, too, that year.)

The UNESCO description of France’s repas gastronomique 25begins with windy talk of “togetherness, the pleasure of taste … the setting of a beautiful table …” Then it hails that timeworn oh-so-French alimentary grammar: the “fixed structure, commencing with an apéritif … and ending with liqueurs, containing in between at least four successive courses, namely a starter, fish and/or meat with vegetables, cheese and dessert.”

Voila, my dutiful plan.

The UNESCO honor was a big cultural deal, greeted by nationalistic headlines like “France Offers Its Gastronomy to Humanity” and “The World Is Envious of Our Meals.” The global reaction, however, was summed up by another British (of course) newsprint jibe, to the effect that while French cuisine might have acquired UNESCO status, its “artery-clogging richness and prissy presentations went out of vogue, along with the old fashioned red-and-white tablecloth.”

And yet here was an inveterate anti-Francophile, me, sitting down now at last, sweat wiped off, at our cramped kitchen table cleared for our “fixed structure” repast … experiencing, perhaps for the first time in my life, a pang of affection for France, for Paris. It was a beautiful museum piece of a meal. We started with apéros of Lillet with œufs mayonnaise and Rousseau-worthy ruby-red radishes with sunshine-yellow butter. Our appetizer proper was that French millennial Instagram darling, pâté en croûte—an architectural Caremian pastry case from the sleek food hall of Galeries Lafayette, housing a mosaic of pork farce, truffles, and foie gras. “Mmmm,” approved my mom as we slathered globs of artery-clogging bone marrow on an award-winning baguette from our local Tunisian baker. Carême’s amber pot-au-feu broth followed, in dainty porcelain cups, succeeded by M. Larbi’s excellent halal boeuf, chicken, and veal, all overcooked by me but not tragically—and concluding with oozy Camembert (France’s “national myth,” 26as one anthropologist called it) and glossy darkly chocolaty éclairs decorated with gold leaf.

“Remember … in Moscow?” Mom panted softly, as she and I sat in the bibelot clutter of the living room, while Barry cursed from the kitchen at the mountain of dirty dishes.

Yes, I remembered … I remembered it well …

BACK IN SOVIET MOSCOW, Paris had featured intensively in my mother’s dreamlife. It was a mythical Elsewhere beyond the implacable Iron Curtain, a neverland desperately dear to her from Flaubert and Zola and her precious Proust, but so unattainable it could have been Mars. She was a yearning, romantic Francophile stuck in our ghastly Moscow communal apartment reeking of alcohol and stale cabbage. When Mom made her own thin cabbage soup, she’d call it pot-au-feu, announcing that she’d read about it in Balzac’s Cousin Pons. She hadn’t a clue what a “bon pot-au-feu” tasted like, but the name was aromatic with her yearning.

“Remember in Moscow?” she repeated. “Eating my make-believe pot-au-feu? Dreaming of Paris?”

IN RETROSPECT, maybe I’d never forgiven Paris for the trauma of our first visit.

A couple of years into our American refugee life in Philadelphia, we finally got our “stateless” white vinyl passports. Mom was cleaning houses for $15 a day, but somehow she saved up for a trip to the city that had so thoroughly enthralled her from afar. 27

And Paris?

Paris greeted us with profound, crushing indifference: a stern unwelcoming finger-wagging abstraction of European civilization with its stony oppressive Haussmannism, its undreamy reality. The rain came down nonstop.

Mealtimes were the dreariest. We craned from outside the windows of Bofinger for glimpses of towering seafood plateaus we could never afford. We stared, from an intimidated distance, at the sidewalk savoir vivre at overpriced Flore. Our own dining in this kingdom of gastronomy mostly consisted of discounted Camembert shrill with ammonia, stale saucissons, and even staler moussaka from Latin Quarter Greek menus touristiques. My poor mom, besotted with her literary narratives of Paris. She did splurge on half a dozen Balzacian oysters, slimy revolting things to my thirteen-year-old palate—although not as traumatic as the rare tournedos with sauce béarnaise at a shabby bistro in honor of her beloved Moveable Feast of Hemingway. The garçon removed the uneaten boeuf with a look. In Philadelphia we’d been homesick, alienated, and destitute; but never humiliated. Paris could accomplish the latter with one imperious raise of an eyebrow. I still remember myself, a sulky émigré teen in polyester hand-me-down clothes, face glued to the chichi Samaritan window displays. How I wanted to twist the pert Parisian noses of mannequins modeling their ooh-la-la scarves—unaware at the time how the shaming of wide-eyed provincials was an enduring Parisian trope, part of the national narrative.

THERE IS SOMETHING called “Paris syndrome,” so I’d learned on this visit from the young Japanese owner of a chic tiny coffee spot 28in the Marais. This affliction, pari shōkōgun, was the extreme shock suffered by dreamy Japanese visitors at the reality of Paris versus the myth. What traumatized them was that instead of Chanel-clad couples toting Louis Vuitton bags along cobblestone streets en route to romantic bistros, they encountered a scruffy globalized metropolis full of junk food and street trash and ugly scenes in the metro. My own feelings, however, were exactly the opposite—a reverse Paris syndrome. Gradually, day by day, my monthlong encounter with this real Paris liberated me from its tyrannical narrative, from my own projections and fears about the oppressive weight of its culture, its gastronomic ponderousness. And now with my pot-au-feu project behind me, I could feel something like happiness here enfin.

Mom was to depart the following afternoon for New York. Barry and I were headed on to Naples, then to Tokyo, Seville, Oaxaca, and Istanbul to probe their national food narratives. The task had seemed to me straightforward at first, but already appeared more complex and elusive—entangled with the paradoxes and fictions of history, and hinting at the surprising Möbius strip realities of globalization. For our last night in the City of Light, we raided the fridge with its In Jackson Heights poster for remnants of our “meal of the French.” All that remained of our once-vast pot-au-feu was a quart of bouillon. For inspiration I scoured our hosts’ packed cupboards. There, among jars of Fortnum & Mason piccalilli, Chinese chili pastes, and Moroccan harissa sat a plastic tub of instant Vietnamese pho cubes. I dropped a few in Carême’s simmering amber bouillon, garnished our bowls with lime and cilantro, and we ate this improvised “pot-au-pho,” our ersatz homage to French cuisine’s postnational narrative, around our cramped kitchen table.

NAPLES

Pizza, Pasta, Pomodoro

Within twenty-four hours of arriving in Naples later that year I’d made my very first pizza napoletana. It was the iconic pizza Margherita, of course—ablaze with the patriotic tricolore of the Italian flag and strictly codified: red San Marzano tomatoes, white mozzarella di bufala, buoyant green basil. According to legend, it was named to honor the blond queen of unified Italy from the Piedmontese House of Savoy, who so enjoyed it on a visit here to the South in 1889 that as a royal populist gesture she allowed it to be called after her.

I didn’t come to Naples, though, to join the thin ranks of female pizzaiole. I came to this former capital of kingdoms—where Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Normans, Spanish, and French had ruled before the unification of Italy that was completed in 1871—to sound myths of italianità and, more specifically, napoletanità. To better understand pizza and pasta al pomodoro, the uncontested twin staples of the Neapolitan poor, which through migration spread “Italian” food culture worldwide—then became so relentlessly globalized 30they seemingly lost all connection to the teeming, histrionic city that spawned them.

Not that Neapolitans will ever let you forget the connection.

“The croccante [crisp] ‘pizza’ of Florence or Germany?”

Davide Bruno, my vigorous, athletic pizza instructor, was practically sneering. “The doughy focaccia that passes for pizza in New York? Pathetic surrogates, all of them!”

Everything was born out of Neapolitan pizza, insisted Davide—pronouncing “everything” (tutto) with an explosive force that suggested a cosmic Big Bang responsible for all life forms on the planet. And the father of Neapolitan pizza? “The Neapolitan genius of hunger.” An early note of Naples’s perpetual aria of self-mythology I’d be hearing a lot of.

At the time, Davide ran the Pizza Academy of La Notizia, a pizzeria owned by my friend Enzo Coccia, the greatest pizzaiolo of Naples. My debut Margherita was the culmination of a sweaty morning session with Davide and a gangly, blond fellow-student, Mo (short for Moritz), who had a pizza equipment business in Hamburg. Mo and I had spent the morning dutifully squeezing apple-sized balls called panetti from a big blob of slowly fermented dough, and then learning how to deftly use our fingertips to flatten the panetti. Then we struggled hopelessly to execute the virtuoso sideways flip for achieving perfectly round discs. In between bad-mouthing non-Neapolitan pizzas and Mo for tearing his dough, Davide expounded on the thermodynamics of the special domed Neapolitan oven. This 850°F inferno, resembling to me a fantastically white ash-covered grotto, is fueled by two woods: fast-burning beech teamed with slow-burning oak. The combo produces the three modes of heat—convection, conduction, irradiation—needed to bake the pizza in just ninety seconds. 31

My Margherita emerged from the glowing bowels of the oven slightly misshapen, its tomato sauce applied in nervous amateur splashes rather than suave circular sweeps. Trying to waggle it off the pizza paddle, I managed to slump it into the ash, so that now dark flecks disturbed the patriotic red, white, and green. Still. My first bite brought me somewhere close to elation. My Margherita tasted, well, it tasted like a true pizza napoletana, a terse modest essay in smoke, air, and acidity ringed by a textbook-perfect cornicione, that crucial inch of raised border that rises up in a flash when you flatten the dough disc—somehow—just right.

“Molta emozione, eh, la prima pizza?” declared Davide. “Un po’ bruttina, ma tua.” A little ugly, but yours. He took a cautious bite.

“Almost edible.”

I planted a kiss on his sweat-seasoned cheek.

BARRY AND I HAD arrived in Naples the previous late afternoon, in classic Neapolitan style. Our airport taxi driver didn’t grumble at our mountain of luggage. But he seemed agitated by where we wished to go: the sixteenth-century warren of lanes known as the Spanish Quarter. After much rocketing along, we got bogged down in a vast clog of construction near the port. Then suddenly we wrenched up into a maze of shadowy, tilted vicoli—the Quartieri Spagnoli. Turn followed absurdly tight turn; our driver grew more agitated, more bitterly operatic. Also, ominously, his meter was running, despite the list of set fares angled against the back of his seat. Up and up we wrenched, doubled back, doubled back again. Abruptly, we slammed to a halt. 32

We were at a small scrappy piazzetta out of a neorealist film. Blotched and peeling six-story buildings loomed overhead in the frazzled end-of-afternoon light; laundry sagged from humid balconies. Motorini wriggled up, buzzing and beeping like angry wasps, shot away. A group of mostly shaved-headed, heavily tattooed guys were milling around a betting shop; a soccer match was screening beside an enormous rampant visage of Diego Maradona, Naples’s saint-devil of calcio. Two pit bulls roamed under him, unleashed. We took all this in chaotically while the cabbie unloaded our bags onto the grimy lava cobblestones. He announced the fare: double the listed price. Outraged, I protested in my standard Italian. Gesturing vehemently with clasped hands he counterprotested, crying Molto bagaglio! in an emotion-thickened Neapolitan accent. Cheating! I shouted back.

A crowd gathered at our time-honored spectacle: the Fleecing of the Tourist. A scooter with a burly woman, two kids, and a bulldog stopped to watch. Finally Barry yanked out his wallet and shoved some bills at the driver. Who took the money, gave a last outburst of hands and protests, slammed his taxi door, and drove off.

We’d arrived in Naples.

Our rental lay on the other side of the piazzetta. Top floor, no elevator. “The dwelling houses of Naples,” Mark Twain exclaimed in 1869, craning his neck, “are the eighth wonder of the world … a good majority of them are a hundred feet high!” (Twain also complained of overcharging.) A pale imperious professoressa of Shakespeare awaited us, and our bagaglio, up at her vast apartment. She gave us a quick, preoccupied tour, handed over the keys, bade us arrivederci, and left.

We stood on her sprawling rooftop terrazza. Straight ahead in 33the distance a slope of Vesuvius rose like a shoulder of a stone Godzilla. Behind us, the landmark bulk of the Carthusian monastery complex of San Martino towered into the arching pink grapefruit sky. We’d arrived in Naples indeed.

The kitchen was barren save for a tightly sealed glass jar of blood-red tomatoes in an otherwise empty fridge, and three opened packs of spaghetti in a drawer. Too tired to go foraging in the piazzetta, I decided to improvise a spaghetti al pomodoro. It would be a salute to our first Neapolitan evening, and the start, plunging straight in, to the progressive monthlong “meal” I’d promised myself would consist of nothing but pizza and pasta—an epic carbon-carb research overload. Quick-reduced in the last inch of the professoressa’s nice olive oil, my pomodoro had an unexpected, almost urgent intensity, unadulterated by the missing garlic, basil, and cheese. Was it because the tomatoes were megaheirlooms, picked at the height of a Campanian summer and put up by the professoressa’s wrinkled old nonna? Or were we just famished? I thought of those iconic nineteenth-century tourist images of the ravenous Neapolitan poor gulping spaghetti by hand. And how it was here in Naples where Italy’s first pasta-tomato-sauce recipe—“vermicelli con le pommadore”—appeared in print in 1839 in a cookbook written in Neapolitan dialect by a gentleman called Ippolito Cavalcanti, Duke of Buonvicino.

Does food taste different when we imagine it embodies a genius loci—a spirit of place?

We pondered this at a rickety low table on the terrazza with some of the professoressa’s sticky-sweet limoncello, which Barry had savagely chilled. From the piazzetta below, the preening schmaltz of a neomelodico song—the music of today’s Neapolitan mean 34streets—was chorused by sudden angry barking, shouts, the harsh beeps and buzzing of mopeds. A bottle smashed loudly against a graffitied wall. And under the early stars, the slope of Vesuvius was a lingering cement-gray rosy-brown, an ancient, exhausted voluptuousness, a monumental chunk of faded fresco.

This was Naples, a città doppia, the eternal duality of its splendor and urban squalor.

It was the mid-eighteenth-century discovery of Herculaneum’s and Pompeii’s ruins that fixed Naples and its beautiful and dreadful volcano as a highlight on the Grand Tour, launching a tradition of relentlessly stereotyping the city, by both outsiders and locals. And most every traveler since has remarked on the duality we were now experiencing. True, Goethe called Naples “a paradise.” But opinion more inclined to the view long attributed (falsely) to Mary Shelley: “Naples is a paradise inhabited by devils.” We went to bed and read some of Norman Lewis’s Naples ’44, his comic-appalling account of the bombed-out starving city right after liberation in World War II. Lewis was headquartered as a British intelligence officer a short walk from our Quartieri Spagnoli, in a palazzo down by the seafront of Chiaia. He witnessed Vesuvius’s latest eruption, in 1944. It was, he wrote, “the most majestic and terrible sight I have ever seen, or ever expect to see.”

PIZZARIA LA NOTIZIA 53, the site of my Margherita debut, sits on a residential street in the Vomero district, part of the airy bourgeois Upper City. My taxi took me on a looping ascent along sweeping bay vistas that sent Grand Tourists into tizzies. On the horizon floated Ischia and Capri. 35

Enzo Coccia, La Notizia’s fiftyish owner, was running late when I got there. Preservationist/ur-traditional baker, philosopher, author of a densely scientific treatise on pizza, Enzo has three very distinct pizzerias along this street. He also stars in documentaries on pizza, propounds on pizza to visiting dignitaries, jets around the world consulting on pizza. His regulars include the president of the Napoli soccer club and the city’s top intellectuals. Il Pizzaiolo Illuminato—the Enlightened One—he’s called.

Il Illuminato finally rushed in, a trim, ebullient figure with chic rimless glasses and a tomato-red pizzaiolo kerchief above a T-shirt emblazoned with the name “Ancel Keys,” the American physiologist who coined the term “Mediterranean diet” in the 1950s.

“The status of a Neapolitan pizzaiolo,” exclaimed the Enlightened One, kissing me ciao, “has changed! We were the lowest, dirtiest of artisans—brutal work, zero respect, poco money. And now?” He gave a derisive laugh. “Now these teenage pizzaioli, these shameless Instagrammers who barely know the tomato varieties—they hire publicists!”

“But Enzo,” I pointed out, “you have a fancy Milan PR firm.”

“I earned it!” quipped the Illuminato, showing me the scars on his hand—multiple carpal tunnel surgeries.

When I first ate pizza in Naples back in the late 1980s, pizzaioli were anti-Illuminati in wifebeaters and clunky gold chains. They dressed their pies to match, with unpedigreed canned tomatoes and cheap cow’s milk fior di latte cheese, not today’s fancy mozzarella di bufala. Achieving an authentic pizza apotheosis back then was pretty straightforward. Claim a worn marble table at an old-school dive, say Da Michele or Di Matteo, in the then-dangerous Spaccanapoli quarter. Order up a rigidly minimalist pie blistered and charred by the 800°F oven—so shockingly different from the 36doughy-gooey slices celebrated in New York’s Little Italy. Over a chipped glass of bad wine, hearken to the pizzaiolo invoking passione and sacrificio and the holy pizza commandments outlined by the Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana, an organization founded in 1984 to protect pizza’s unique Neapolitanness at a time when safeguarding “cultural heritage” became a serious preoccupation in Europe, in response to globalization.

A vera (true) pizza napoletana, one learned, had to be the size of a plate, with slow-leavened dough kneaded and stretched out by hand (never rolled) before its brief stint on the floor of the forno. Puffy in spots with a blistered one-inch cornicione, la vera pizza was to be topped with no more than a smear of red marinara sauce and perhaps some mozzarella and basil for Margherita—e basta. “Fancy” pizza topping? Contaminazione.

“We scribbled down those Associazione commandments by hand, too!” Enzo was grinning merrily now. “In our first real attempt to codify what had been for centuries solely an oral Neapolitan tradition.”

Until pizza went global post-WWII, the adjective Neapolitan wasn’t added just for chauvinism or protectionism. In the Italian culinary lexicon, pizza simply means something crushed flat. From the Renaissance to the late 1800s, printed pizza recipes often involved sugar and almonds. What’s more, as a form, Enzo noted, pizza is archaic, ur-universal—a flatbread related to Indian naan, Mexican tortilla, Arabic pita. “A form,” I put in, “that followed function? A pre-utensil edible plate, perhaps, akin to the ancient Roman mensae and the medieval bread-plate called a trencher?” We both agreed that the ongoing debate over pizza’s etymology—pinsere? picea? bizzo? pitta?—suggests its universality. 37

“So then, Enzo: What exactly made it Neapolitan?”

“Local condimenti