Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

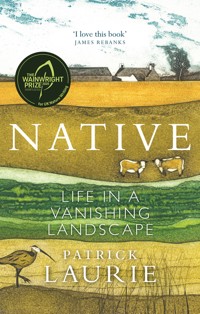

A Times Bestseller Shortlisted for the Wainwright Prize for UK Nature Writing 2020 'Remarkable, and so profoundly enjoyable to read ... Its importance is huge, setting down a vital marker in the 21st century debate about how we use and abuse the land' - Joyce McMillan, Scotsman Desperate to connect with his native Galloway, Patrick Laurie plunges into work on his family farm in the hills of southwest Scotland. Investing in the oldest and most traditional breeds of Galloway cattle, the Riggit Galloway, he begins to discover how cows once shaped people, places and nature in this remote and half-hidden place. This traditional breed requires different methods of care from modern farming on an industrial, totally unnatural scale. As the cattle begin to dictate the pattern of his life, Patrick stumbles upon the passing of an ancient rural heritage. Always one of the most isolated and insular parts of the country, as the twentieth century progressed, the people of Galloway deserted the land and the moors have been transformed into commercial forest in the last thirty years. The people and the cattle have gone, and this withdrawal has shattered many centuries of tradition and custom. Much has been lost, and the new forests have driven the catastrophic decline of the much-loved curlew, a bird which features strongly in Galloway's consciousness. The links between people, cattle and wild birds become a central theme as Patrick begins to face the reality of life in a vanishing landscape.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 348

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Native

For my parents

First published in Great Britain in 2020 byBirlinn LtdWest Newington House10 Newington RoadEdinburghEH9 1QSwww.birlinn.co.uk

ISBN: 978 1 78885 257 9

Copyright © Patrick Laurie 2020Illustrations copyright © Sharon Tingey 2020

The right of Patrick Laurie be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

Typeset by Biblichor Ltd, EdinburghPrinted and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Blows the wind to-day, and the sun and the rain are flying,Blows the wind on the moors to-day and now,Where about the graves of the martyrs the whaups are crying,My heart remembers how!

Grey recumbent tombs of the dead in desert places,Standing stones on the vacant wine-red moor,Hills of sheep, and the howes of the silent vanished races,And winds, austere and pure!

Be it granted me to behold you again in dying,Hills of home! And to hear again the call;Hear about the graves of the martyrs the peewees crying;And hear no more at all.

Robert Louis StevensonVailima, Samoa (1894)

CONTENTS

Maps

Beginnings

Granite

Hills

Whaup

Grass

Crop

Calves

Hay

Bull

Harvest

Mart

Endings

Acknowledgements

Galloway

The Farm and Surrounding Area

BEGINNINGS

Winter Solstice – the Shortest Day

I peer through an open window in the darkness. The morning feels warm, and the fields click and chatter as they drain the night’s rain. Drips plop off gutters in the yard and a curlew calls. Our cockerel answers from the shed, and his din makes the tin roof ring.

Curlews vanished from the glen when the weather was cold, but they returned within hours of the thaw. Large winter flocks come inland from the sea and probe the sodden ground with long, curved beaks. I take the dogs out before breakfast and find the half-light filled with the sound of wading birds.

Our stretch of the river was straightened many years ago. Men dug a new and more efficient path for the water, but they failed to iron out the old bends. The river follows a straight and perfect line through the dark soil, but you can still see where the old stream used to play in swampy, tangled loops. Heavy rain can bring this waterway back to life – subtle contours flood again and become strings of narrow pools, pouchy old veins which bristle with reeds. The new river rushes water briskly out to sea. The old one hoards the rain and refuses to let go.

Curlews cluster in these haunted, sodden corners. The dogs flush them as the day brightens, and they wail in the falling rain. Drainage pipes were buried across these fields to bail water into the river, but after years of service they are beginning to fail. The terracotta tiles are breaking and the water has started to flow backwards. Without human intervention, the river will begin to resume its ancient course – the curlews pray for it.

The new bull calf bellows when he hears me open the back door after breakfast. His shed is across the yard, and he listens to every move we make. He was timid and small when he arrived here on the lorry from Kendal. He sorely missed his mother, but now he is growing in confidence and roars to be fed. Dull days and low cloud reduce him to a dark silhouette in a pool of straw. There are no electric lights in this shed, but we can make out that he has a fine head. It is heavy and square like a Belfast sink, and the curls grow so thickly upon it that they swallow my fingers to the knuckle. I rub his brow and stir up delicious scents of sweat and dry grass. His blue tongue rasps at my cuff and I turn to stare out through the open doorway. I am seeing the world from his perspective and realise that this rectangular hole is like a cinema screen to him. He lurks in the gloom and the days purr by in a flick-book of still images, alternating phases of blue, grey and darkness. He watches endless repeats of wild swans on the bottom fields. Owls star in his nights.

Everyone agrees that he’d be better outdoors. This animal was bred for wide open spaces, but I have no other options and there are some advantages to this early confinement. He might roll his eyes and moan but he can settle here without coming to harm, and he can get to know us. Buying him was a gamble, and now I’m relieved to feel it paying off. It is hard to tell how a calf will be as an adult, but this lad has promise.

A starling dies at noon. I watch the falcon peeling the corpse from the kitchen window as I fry an egg. The day is already over and the fields begin to recede beneath a veil of thin, chesty cloud. Later I will find most of the starling’s skull amongst a mess of feathers. It is a glossy ball which reminds me of a cape gooseberry; a discarded garnish.

Night falls with a rush of wildfowl. Ducks whoop in the deep blue, and the shapes of birds flare over the yard as I chop firewood. Then there is swirling rain which dances like smoke in the light of the kitchen window and lacquers the granite setts of the yard. It is only four thirty and a vixen is screaming for attention on the moss. The dogs cough to respond for a moment, then they jostle past my knees and back to the hot stove.

From this distance, summer feels like another place. I can hardly remember the sun, but now the darkening has slipped into reverse. Months of gradual compression will begin to relax, and daylight will leak back into our lives. It will be weeks before human beings can register the lengthening days, but the shift has been clocked by others. This wet, draining place is on the move at last.

*

Galloway is unheard of. This south-western corner of Scotland has been overlooked for so long that we have fallen off the map. People don’t know what to make of us anymore and shrug when we try and explain. When my school rugby team travelled to Perthshire for a match, our opponents thumped us for being English. When we went for a game in England, we were thumped again for being Scottish. That was child’s play, but now I realise that even grown-ups struggle to place us.

There was a time when Galloway was a powerful and independent kingdom. We had our own Gaelic language, and strangers trod carefully around this place. The Romans got a battering when they came here, and the Viking lord Magnus Barefoot had nightmares about us. In the days when longboats stirred the shallow broth of the Irish Sea, we were the centre of a busy world. We took a slice of trade from the Irish and sold it on to the English and the Manxmen who loom over the sea on a clear day. We spurned the mainstream and we only lost our independence when Scotland invaded us in the year 1236. Then came the new Lords of Galloway and the wild times of Archibald the Grim, and he could fill a whole book himself.

The frontier of Galloway was always open for discussion. Some of the old kings ruled everything from Glasgow to the Solway Firth, but Galloway finally settled back on a rough and tumbling core, the broken country which lies between tall mountains and the open sea. This was not an easy place to live in, but we clung to it like moss and we excelled on rocks and salt water both. We threw up standing stones to celebrate our paganism, then laid the groundwork for Christianity in Scotland. History made us famous for noble knights and black-hearted cannibals. You might not know what Galloway stands for, but it’s plain as day to us.

We never became a county in the way that other places did. Galloway fell into two halves: Wigtownshire in the west and the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright in the east. There are some fine legal distinctions between a ‘Shire’ and a ‘Stewartry’, but that hardly matters anymore because both of them were deleted in 1975 when the local government was overhauled. The remnants of Galloway were yoked to Dumfries, and the result is a mess because Dumfries and Galloway are two very different things.

Dumfriesshire folk mistake their glens for dales and fail to keep Carlisle at arm’s length. They’re jealous of our wilderness and beauty, but we forgive them because it’s unfair to gloat. Besides, they have the bones of Robert Burns to console them, and don’t we all know it. Perhaps Dumfriesshire is a decent enough place, but we’ve pulled in different directions for too long to make an easy team. Imagine a county called ‘Perth and Fife’ or ‘Carlisle and Northumberland’. Both would be smaller and more coherent than ‘Dumfries and Galloway’. Now there are trendy councillors who abbreviate this clunky mouthful to ‘D ’n’ G’, as if three small letters were enough to describe the 120 miles of detail and diversity which lie between Langholm and Portpatrick. Tourism operators say we are ‘Scotland’s best-kept secret’, and tourists support that claim by ignoring us.

It’s easy to see why visitors rarely come. They think we’re just an obstacle between England and the Highlands. They can’t imagine that there’s much to see in the far south-west and tell us that ‘Scotland begins at Perth’. Maybe it’s because we don’t wear much tartan, or maybe it’s because we laugh at the memory of Jacobites and Bonnie Prince Charlie. Left to our own devices, we prefer the accordion to the pipes and we’d sooner race a gird than toss a caber. If you really want to see ‘Scotland’, you’ll find it further north.

When Galloway folk speak of home, we don’t talk of heather in bloom or the mist upon sea lochs and mountains. Our place is broad and blue and it smells of rain. Perhaps we can’t match the extravagant pibroch scenery of the north, but we’re anchored to this place by a sure and lasting bond. There are no wobbling lips or tears of pride around these parts; we’ll leave that sort of carry-on to the Highlanders. We’ll nod and make light of it, but we know that life away from Galloway is unthinkable.

My ancestors have been in this place for generations. I imagine them in a string of dour, solid Lowlanders which snakes out of sight into the low clouds. These were farming folk with southern names like Laidlaw and Mundell, Reid and Gilroy, and they worked the soil in quiet, hidden corners without celebrity or fame. Lauries don’t have an ancestral castle to concentrate any feeling of heredity. We’ve worked in a grand sweep between Dunscore and Wigtown and now all of Galloway feels like it might’ve been home at one time or another. I was born to feel that there is only one place in this world, and I can hardly bear to spend a day away from it. Satisfaction alternates between quiet peace and raging gouts of dizzy joy.

Wild birds fly over Galloway. They move between the shore and the hills, and that journey brings them close at hand. I was brought up on a seaside farm where curlews spent their winter days in noisy gangs of a hundred and more. My father ran a mixed business based on sheep and beef cattle, and curlews flowed alongside him in rich furrows by the shore. When spring comes, curlews are blown uphill on warming winds to breed on the moors, and we followed them a few miles inland to pass many hours at work on my grandfather’s hill farm. I heard the birds crying on busy days when the sheep were clipped and the peat was cut.

Unremarkable in flight, obscure in plumage and secretive to the point of rumour, curlews are unlikely heroes. But then they call over the shore and sing beneath the high-stacked clouds and there is nothing else of value. No other wild bird has that power to convey a sense of place through song. It’s a grasping, bellyroll of belonging in the space between rough grass and tall skies, and you never forget it. The curlew’s call became the year-long sound of my childhood. I hear that liquid, loving list and I’m lying in the warm, sheepy grass again, a small boy in too-big wellies, hugged by old familiar hills.

So I thought that curlews were mine. The connection was a livewire, but then I found that the birds had a place in all of us. My entire family would rush to the kitchen door at night to hear curlews passing between our chimney and the wide, dusty moon. We all loved them, so then I began to think that the birds belonged only to Galloway. In time I’d grow up and go elsewhere, and that’s when I learned that curlews are loved by anybody who’ll take the time to listen to them. People are devoted to curlews in Wales and Ireland, on Shetland and Exmoor; the birds have starred in heraldry, tradition and folklore for thousands of years. Everybody is tempted to claim the curlew, and no other bird can boast of such universal popularity.

I wrote about curlews as a teenager when my friends were smoking and chatting up girls. I hunted for more information about the birds through old school encyclopedias, but all I found were dry, papery sentences which were dull as windblown sinew. I went back to those words again and again, hoping that I could read some flesh onto the bare bones –

Curlew: any of numerous medium-sized or large shorebirds belonging to the genus Numenius (family Scolopacidae) and having a bill that is decurved, or sickle-shaped, curving downward at the tip. Curlews are streaked, grey or brown birds with long necks and fairly long legs. They probe in soft mud for worms and insects, and they breed inland in temperate and sub-Arctic regions of the Northern Hemisphere.

The common, or Eurasian, curlew (N. arquata), almost 60 cm (24 inches) long including the bill, is the largest European shorebird. This species breeds from Britain to Central Asia.

There was so little to go on. I began to write my own encyclopedia entries in the form of short descriptions and reports of encounters with the birds on the hill and the sea shore. I don’t know what became of these projects – perhaps they have survived in jotters and folded pages stowed in the attic. It hardly matters, but the birds called me to stretch my legs and draw lines between known and unknown. Curlews were both, and I clung to them through adolescence and early adulthood. Their calls began to feature in tales of fumbling romance and the pressing growth of responsibility. They grew to fill more than just a blue-remembered childhood. I began to think they were an ever-present fact of life, as dependable as rain and moonlight.

Young people don’t stay in Galloway. They go to Glasgow, and I went with them for a four-year stint at the university. The city was a clashing novelty, but then I graduated and found summer work on a Hebridean fishing boat. It was a dark morning on the bus from Buchanan Street to Uig, and rain lashed against the sweaty windows. An old Hebridean lady had made a fruit cake for the journey and passed it around the passengers as we slashed our way through Glen Coe. The work was a lunge at something different, and soon I was watching killer whales pass our small boat at dawn against the silhouette of Skye. Here was a fine place, but I was nagged by the knowledge that this was not my home. I didn’t have the Gaelic, and I watched my friends at arm’s length. They were born and raised on the Outer Isles, and I wondered how it would feel to have roots in that shallow, turquoise water. I was just paddling my toes in their world and I began to feel like a fraud. I envied the Dutch and German tourists who gawked at us on the jetty because they had nothing to prove.

The work also showed up my physical weakness and lack of stamina. I slobbered with tears and exhaustion after eighty-hour weeks, and I was forever shamed by the strength and power of men three times my age. We went over to Portree for a drink and one of the boys got into a fight. I was pathetic and fragile, and I ducked outside. There was crashing and swearing, and I growled on the harbour steps like a dog pretending to strain on its lead. I didn’t want to fight, but it was galling to find that I couldn’t if I tried. Soft-handed people like me often say that manliness doesn’t matter anymore. We make it seem dumb and old-fashioned, but I grew up around capable, bull-necked men and there was no hiding from the shortfall. I said that I came back to Galloway because I had other plans. Weakness is closer to the truth.

And it was good to be home. Galloway poured back into my boots like peaty water, but it was hard to find solid footing in this place. I’d studied language and literature, but there wasn’t much use for either in small towns where most of the shops are boarded up and jobs are hard to find. Our glory days are well behind us, and D ’n’ G has slumped into decay. People say the best chance you’ve got of making money in Galloway is to buy a metal detector and spend your days hunting for your ancestors’ gold.

I spent a few seasons drifting around south-west Scotland. I picked things up and replaced them again, I pulled pints and felled trees, and finally found some cash in freelance journalism. It paid the bills, but this line of work hardly carries much clout in a place where you’re expected to have a one-word job title and you just get on with it. People asked ‘what do you do these days’? I’d shrug and say ‘all sorts’, knowing that I’d fail to cut mustard.

My Cornish wife and I were married in the registry office in Glasgow. We’d met at university and we moved to a small cottage by the Solway shore where we could listen to curlews flying in the darkness. We assumed that our children would not be far away, but none came, so I leant back on married life with a shrug. Work was busy and time swirled past. I didn’t mind the absence, and I felt sure that our family lay just around the corner. Years later, we’d recall this place during brusque interviews with a fertility specialist who asked us when we began ‘trying’ for a baby. It was in those days, but babies were one of many plans we had back then.

I returned to curlews in a loose, half-hearted kind of way. I liked the idea of writing a book about the birds, and the sudden collapse they’ve suffered over the last thirty years gave them a glaring relevance. We hardly need scientists to tell us that curlews have been declining across Britain over the last half-century. The birds used to be absurdly common, and now they are nearly gone. We’ve lost three-quarters of our curlews in Galloway since the 1990s, and some parishes have lost them all. I was old enough to have seen this collapse in real time. My nagging worries had become a constant ache; this is the latest disaster in a long and nationwide sequence of decline and collapse, but this one really hurts.

I began to examine curlews beneath a microscope. I gathered up mounds of scientific reports and started out on background reading, but the work was hard and I stumbled over the technical jargon. I’m no scientist; I had to launder ideas of ecosystems and biodiversity into something I could understand. People in Galloway aren’t used to thinking about wild birds in isolation. They’re part of something much bigger, and they hardly warrant anybody’s full attention.

Visitors come and tell us that we live in a fine place to watch birds, but we’ve always taken our wildlife for granted. Problems have only arrived here in the last few decades, and we’ve been spoiled by centuries of surplus. We’ve gorged on wild partridges and salmon for a thousand years, and now we are told to be careful with what we have because nature is fragile. True enough, our salmon have gone and our game is going, but we aren’t sure what to make of birdwatchers and ecologists. They come from somewhere else and they usually tell us we’re wrong.

I began to think that a book about curlews would’ve made no sense to my ancestors who’d farmed here and were preoccupied with soils and rain, beasts and grain. The birds were hardly worth noticing in the days of their prosperity, but now curlews have been transformed by their decline. They’ve become figures of tragedy to be studied in desperate detail. Everybody mourns the loss of curlews, but birds have always come naturally to us and we scratch our heads at this confusing failure.

I was besotted with birds. Curlews were my focus, but I’d often get up before dawn to watch black grouse and lapwings displaying in the rushes above the hill pens. I’m glad I made the time for those birds because they’ve all gone now. I knew the last black grouse by name, and I was there to see the final lapwing’s egg. Curlews are the last of a grand dynasty of hill birds which has crumbled into ash during the short course of my life. My generation has arrived at a party which seems to be ending, and it’s getting harder to recall birds as they were in the days of their plenty.

People often say that agriculture has driven this collapse. There’s a long-running conflict between conservationists and farmers, and I was caught with a foot in both camps. Birdwatchers say that farmers don’t give a damn about wildlife, but I couldn’t square that with what I saw at home. My love of nature had always been egged on by my parents, who nudged and fired me up with their own stories and tales. My father used to bring me small treasures he’d found on the farm: I had an owl feather and a snake’s skin on my bedside table. I was devoted to a dead mole which I carried everywhere in my jacket pocket for two weeks. I loved ‘him’ (or her) with desperate intensity, but this divine jewel went missing in mysterious circumstances. It took almost twenty years for me to realise that my parents had thrown the corpse away when it had finally sprung a leak and begun to melt.

My family was fascinated by nature, and many of our friends had an amazing wealth of knowledge about birds of all kinds. Some of these were hard-handed gamekeepers and deerstalkers who often slept on the open hill and knew magical details about rough grass and wide skies. They knew where to find deer kids in the bracken, and they watched the owls go down to roost. I gobbled up their stories and made them my own. I was just a boy, and I blurred the lines between truth and fiction.

I didn’t realise that much of that wisdom was already muddled into mythology, and I swallowed it all without checking. I learned more about hen harriers from one old gamekeeper than I have from any book or study since, but the same man avidly believed in the craigie heron, a long-necked bird which prods for frogs by the light of the full moon. Craigie herons aren’t magical or special beyond the realm of other birds; they just don’t exist. But I believed in them like any kid would because the world is big and complicated, and I had no reason to suspect anything else.

Tales like these were ten a penny before the arrival of modern science. Galloway used to be full of tales about evil birds and lucky beasts, but now we have myth-busting experts working hard to break up that kind of nonsense. Ecologists say the worst thing you can do is muddle up fact and fiction, and they sneer that we didn’t know much about wildlife until they arrived to set the record straight. And we don’t like being laughed at, so we learn to keep old stories to ourselves. Maybe we suspect that we’re behind the times, so we tuck our fictions away and let them wilt in darkness. It’s getting harder to find native tales, particularly now there are structured, uniform ways to think about wildlife. Only children dally with magic, and we tell them the truth when they grow up.

I grew up and began to pull facts away from folklore. By an odd twist, it turned out that many of the real things were magical and much of the old superstition was dull. But if I wanted to write something credible about curlews, I would have to bend into new systems of taxonomy and binomial classification. This wasn’t a good fit for me. Besides, I’d learned a great deal of truth from those ropey old stories. If nothing else, the sheer quantity of birdlore and gossip in circulation seemed to suggest that local people had a deep connection with the natural world. Following that thread, I couldn’t sign up to the idea that farmers did not care about wildlife.

Drifting round my working world, I bumped into a small charity which promoted conservation in agriculture. I managed to find some work on a short-term project, and soon I’d found a grand overlap between farming and curlews. Managed correctly, farms can produce a wealth of wildlife, and human beings are a crucial part of that picture. My short-term project became a long-term job. I was assigned to follow some case studies where cattle were used to improve the land for curlews in Wales. Then I was asked to document a similar project in Perthshire. Over the course of several years I started to understand how the relationship works between food and wild birds. I travelled miles to stare at that buzz of goodness which flares up between cattle, humans and wildlife in Powys, Selkirk and Angus. I envied the farmers who were delivering results and were pumping new curlews into the sky every summer against the odds. These people didn’t have advanced degrees or university jobs. They were normal folk like you and me, and I began to wonder if I could join them.

As a child, my sole ambition was to farm and raise livestock like my family had before me. I was gagging to pick up the baton and carry it forward, but the world intervened. Small farms had been trickling away for years, and ‘mad cow disease’ would quickly sink those who hadn’t already jumped. Not long before my seventh birthday, my father crossed into the law and became a solicitor. His farm sank behind him and was gone. He leased the land to a series of tenants – bigger farmers who recognised that the only hope of survival lay in expansion.

My father’s animals were loaded onto a lorry and vanished. The farm became something very different that day. Our fields lost their urgency and relevance. The hill had paid our bills, and now it was merely a place for walking dogs. If it rained, we stayed indoors. Our friends and neighbours fought hard to keep up with the changes in farming, but we were drifting away.

My grandfather was devoted to cattle. Sorely damaged by his time as a fighter pilot in the Battle of Britain, he could match the wildest bull for surliness and bad temper, but he was a superb stockman with a love for his animals. He’d finished the war with the rank of Group Captain, and this is how he was known to friend and foe until the end of his life. He died and left me with fond memories of a red-faced and desperately powerful man in a husky jacket. I thought that his rosy complexion was the product of a robust outdoor life, but I later found that his skin had been seared away in the cockpit of a burning Spitfire as it plummeted into the streets of Wanstead half a century before.

Some of my earliest memories are of visiting his cows at the local agricultural shows. He’d devoted his life to a kind of beast which has deep roots in local history and culture, and his ‘Galloways’ picked up rosettes in Wigtown and Castle Douglas. We think of Scottish beef and conjure up images of windswept red Highlanders with long horns and fluttering fringes, but Galloways are the driving heroes of Lowland farming from Stranraer to Duns. My grandfather’s cattle were jet-black, curly-haired beasts with square, hornless heads and fluffy ears. To outsiders it will seem like a modest claim to fame, but these animals are the finest product that Galloway has ever delivered to the world.

My mother would take me to see my grandfather’s cattle as they lay on beds of fresh straw in the show lines. His farm name was painted on a board which hung above the cows, and the thick-wristed stockmen would wink at me and grin through a haze of cigarette smoke because I was the Group Captain’s grandson. We no longer had cattle at home, but here was a crucial thread of contact with heavy beasts. I don’t remember the animals so well as the paraphernalia which surrounded them – brushes, combs, nets of hay and coils of rope. Results from the judging were recited deadpan across a crackling tannoy: beasts from Rusko and Glaisters, from Barlay and Barcloy, from Plascow and Congeith. I was a small child, and these farm names plotted a complete map of the known universe. Here were my uncles and cousins, friends and family from far-flung places across the Southern Uplands, each with their own Galloway cattle as if no other breed existed. Even at this primal stage and divorced from animals of our own, my life was in orbit around beef.

Galloway has given its name to a breed of cattle, but so has Hereford, Devon and Sussex. There was a time when almost every county or region in Britain had its own breed. Dramatic changes during the twentieth century put paid to many of those old animals, and several weren’t deemed profitable in a modern farmyard. Agriculture was intensifying and animal breeding began to specialise on growth, scale and speed. We said goodbye to Sheeted Somerset cattle, the Suffolk Dun and the Caithness cow, as well as more than twenty other breeds of British livestock between 1900 and 1973. Galloways almost collapsed, and the old animals were replaced by fast-growing bulls from France and Belgium; heavy-lifters with strange and unpronounceable names. Most of the surviving native breeds were reduced to obscurity, just hobby projects for quirky smallholders and stubborn old folk.

But every native breed excels at something special. Tamworth pigs make superb bacon; Gloucester cattle produce milk which cheesemakers adore. Native breeds represent a wide variety of traits, characteristics and flavours which took centuries to refine. High-octane European breeds might have maximised productivity, but this has come at a cost to variety. Our food has been subverted by monotony.

Galloway cows have a particular knack for digesting rough grass. They’re born hungry, and they’ll fatten on feed which many other breeds would refuse to sleep on. A summer heifer fills herself with roughage until she’s as thick and fat as a grand piano, and the grass goes to build sweet, fine-grained beef. The muscle is laid down slowly, and the flavour is matched with a fine, melting texture. The sixteenth-century scholar Hector Boece praised Galloway beef as ‘right delicius and tender’, and modern chefs are titillated by T-bones and rib-eyes which are sold in the best and most exclusive restaurants across Britain. Like many native livestock breeds, Galloway cattle still exist because some people are prepared to pay more for food which ‘tastes like it used to’.

The Galloway’s reputation for superb beef is countered by rumours of violence and awkwardness. In the old days, cattle were cast into the hills and recovered to be killed after four years. These semi-feral beasts grew up to be cunning and insincere. It’s not so long ago that a friend of my grandfather’s was sorely mauled on the back hill, crushed to bits by a cow protecting its calf. I was too young to remember the details, but folk said he should have known better. I imagine him lying in the long grass with his ribs stoved in like a smashed accordion and grand clouds rolling by without a shrug. Arms and legs were broken as a matter of course, and cattle were ‘man’s work’, a gritty, fearsome struggle beneath low, grey skies. It was the perfect job if you’d been scorched by burning aviation fuel and had the strength of five men. Gathering pens were sealed with granite posts and reinforced with railway sleepers – if you came across old pens without explanation you could assume they were built to contain dinosaurs.

It’s easier for everyone when cattle are kept tame and close at hand. There’s nothing inherently wild or dangerous about Galloways, and the beasts are mainly gentle in their way. They’re slaves to their greed, and those heavy, snub-nosed heads can be bound in halters with a little coaxing. Any cow can kill you, and it seems unfair that Galloways should have a bad name.

My work with conservation and curlews had led me back in the direction of farming, but the tipping point came when I walked with my wife around the agricultural show at Castle Douglas and saw the old show lines again. My grandfather had been dead for twenty years and his herd was long dispersed, but here was a line of black cattle standing shoulder to shoulder beneath a rough, burning sun as if they’d not moved an inch in all that time. Perhaps there were not as many of them as there had been, but the animals were utterly permanent. The tannoy returned and I looked up from the bustling show to see fifteen miles of blue hill country towards Carsphairn and Dalry as if it had just sat up in bed. The bold, steady cows had rolled down from that land as surely as rain after a wet night; the purest distillation of place was conveyed in flowing black hair and foamy lips. My knees almost buckled beneath me. Here at last was a true point of entry to my own place. I turned to my wife and whispered, ‘We’re going to have cattle.’ To her eternal credit, she nodded.

Many young people find it hard to get started in farming. The industry looks like a closed shop to outsiders, but my family gave me a foothold as I began to focus on agriculture again. Rather than forge a new road from scratch, I just had to clear some brambles and cobwebs from an existing path. I asked our tenant for advice on getting started and he suggested that I take two of our fields back in hand, the rougher, less productive areas where I could find space for a few calves. The way was strangely clear, and the memory of those black animals at the show fell to a constant, nagging pulse in the back of my brain.

I took a step towards farming and found an old, familiar friend. I could slip in beneath heavy, hairy skins and find a whole new world. After thirty years in Galloway, I was finally heading home.

GRANITE

January

Low cloud and heavy rain.

Wild geese pass over the house in the morning and land in the fields by the river. The water grows fat and sluggish, then it spills its guts onto the grass. The world is reduced to a series of blue silhouettes, and still more rain lashes against the skylight and makes the glass crackle like newspaper.

No good will come of this day, but the cows need hay and the work cannot be postponed. Light, flossy bales come down from the hayshed rafters where mice cheep and scuttle. The bundles smell of sweet summer, but those fond memories are soon quashed and slushy in the mud. The twine is slit and the bales burst into flakes and sodden beasts make mirk with their heavy breath.

Galloways have a long, curly, double coat which can turn away the rain. I watch the water running off their backs and down their sides like a straw raincoat. Their only concession to this weather is to stand with their arses into the wind. They form a corral and the weather breaks upon them as if they were rocks on the shore. Once they have finished feeding, they will return to the shelter of peat haggs, whin bushes or granite scree. These animals are more comfortable outdoors on rough ground than they would be in a shed.

For all the darkness, now is a moment for snowdrops; the first skylark sings in a glimmer of light. These are fine details which might be overlooked in the busy clamour of June or July, but now they are a klaxon and a call to arms after months of starlit darkness; there is life in the world. Going about my work in these brief days, I stack snapshots in passing which combine to make the heart swell – the change is warm and strong.

I see:

The first shelduck on the wet fields, his raucous red bill reflected in a low sun

Toads on the roads, hundreds marching darkly under black and dribbling clouds

Hares running in the frost before dawn, a frizz of excitement from sober old hands.

Two sunlit days stand back to back in a flood of cold rain, and I am dazzled by their frozen mornings. A jumble of mallard cackles as they loop over the bog alders and pass round to the loch. Now is the time for their enthusiasm to spill over; drakes fight in flight for supremacy. Frogs creak in a backwater where teal have roosted the day before; the slimy creeps are couched to their eyes in a foaming soup of sex and spawn.

Snowdrops again, and now four skylarks above the moss. Herds of curlews are breaking up and growing restless for the high hills and the promise of breeding. There is a clean smell of cattle under a cloudless sky. We have two days to feel a vibration of spring, then a tumbling curtain of sleet sets the clock back to winter again.

The Celts used to celebrate this time. They called it imbolc: the first quiet steps out of winter. The word means something like ‘swelling’, and the festival comes when the cows begin to show their udders. Those folk were obsessed with cattle, and it made sense to celebrate the promise of new growth. I was hooked on imbolc when I found it because I was longing for my first calves and could almost feel the ancient excitement of new teats. The Christians tried to undo many of the old festivals, but imbolc left a stubborn mark. In the end, they absorbed the festival and called it Candlemas. I am no spiritualist and I did not mean to mess with pagan gods, but they began to mess with me. There are many ways to make sense of Galloway.

*

After three years by the sea, my wife and I had the chance to move. A farmhouse came up for sale, and some land was offered with it. It was close enough to visit while our supper was in the oven.

The place is visible from the main road, but I’d passed it for thirty years without ever seeing it. Farms like these don’t attract attention. You look through them and see nothing more than a splash of whitewash in a sea of stone, moss and blue, rounded fells.

The farm had belonged to an old boy who lived his entire life here and died at the age of ninety-two. I didn’t know Wullie Carson; I seem to be the only person in Galloway who didn’t. Everybody liked old Wullie, but he saw his retirement coming and lacked a younger man to take the reins. A cold spring killed his love for lambing, so he sold off all but a sliver of his farm to a neighbour and spent the last few years of his life in peace.