Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

Admiral Lord Nelson's diamond Chelengk is one of the most famous and iconic jewels in British history. Presented to Nelson by Sultan Selim III of Turkey after the Battle of the Nile in 1798, the jewel had thirteen diamond rays to represent the French ships captured or destroyed at the action. Nelson wore the Chelengk on his hat like a turban jewel; it became his trademark to be endlessly copied in portraits and busts to this day. After Trafalgar, the Chelengk was inherited by Nelson's family. It was sold at auction in 1895 before ending up at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich where it was a star exhibit. In 1951 the jewel was stolen by an infamous cat-burglar and lost forever. Martyn Downer tells the extraordinary true story of the Chelengk, charting the jewel's journey through history and forging sparkling new and intimate portraits of Nelson, of his friends and rivals, and of the woman he loved.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 505

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

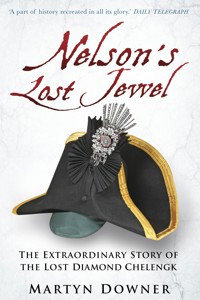

Cover illustration: Replica jewel on naval hat for dress uniform made to Admiral Lord Nelson’s original specifications by Lock & Co., London, 2017. (Author’s Collection)

First published 2017

This paperback edition published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Martyn Downer, 2017, 2021

The right of Martyn Downer to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8611 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Preface

Prelude

1 The Battle

2 The Sultan

3 The Ambassador’s Wife

4 The Hero

5 The Admiral’s Wife

6 The Rival

7 The First Knight

8 The Mistress

9 The Grand Turk

10 The Doctor

11 The Invasion

12 The Farewell

13 The Death

14 The Earl

15 The Bride

16 The Duchess

17 The General

18 The People

19 The Thief

20 The Lost Jewel and its Rebirth

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

PREFACE

Since the first publication of Nelson’s Lost Jewel, two important new documents have come to light which settle some of the questions posed in the book. The first was the discovery of a large Turkish watercolour of the çelenk diamond jewel selected by Sultan Selim III as an award for Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson after the battle of the Nile. The history of this watercolour, which formerly belonged to Nelson’s step-son Josiah Nisbet, will be discussed in the text but it explains why the jewel was so often mis-represented in England. The second breakthrough was finding the original source for the oft-quoted eye-witness account that the jewel which Nelson received at Naples in December 1798 was ‘a kind of feather, it represents a hand with thirteen fingers’. From an unknown correspondent and previously dated to April 1799, I have now identified the writer as Thomas Richards, a young English merchant who dined with Nelson within hours of the jewel’s presentation by the Turkish envoy. Richards’ statement is so at odds with the newly discovered Turkish watercolour of the çelenk painted weeks earlier in Constantinople that the inevitable conclusion is – and this was hinted at in the first edition but, without evidence, left unresolved – that there were two jewels. For reasons which will be explored in this second edition, it is now obvious that before the Turkish envoy departed Constantinople for Naples, the çelenk selected by the sultan was exchanged for another diamond jewel, probably made bespoke for Nelson. The confusion this late substitution caused, to artists and biographers, had persisted until today.

PRELUDE

In January 1839, Admiral Sir Frederick Maitland, commander-in-chief of the Royal Navy in the East Indies, sent a squadron of warships to capture the Red Sea port of Aden. The local Arab tribes put up a valiant resistance, but they were no match for British firepower and the town fell within a day. Aden was the first acquisition of the British Empire during the reign of the young Queen Victoria. To celebrate this auspicious event, Maitland sent six captured guns back to London as gifts for his monarch. The magnificent bronze cannons were Turkish, made for the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman I, ‘Suleiman the Magnificent’, who ruled the region in the sixteenth century. Delighted with her trophies, the queen handed them to the committee then raising a column to Admiral Viscount Nelson’s memory in Trafalgar Square: not to flank the monument, as might be thought, but to be melted down and re-cast. This transfiguration in the furnace saw the guns collapse from cold metal to hot fluid, then to solid again. Today, four of the sultan’s guns survive as the large bronze bas-reliefs on the pedestal of Nelson’s Column depicting the battles of Cape St Vincent, the Nile, Copenhagen and Trafalgar.1 To imperial minds, it was fitting to use captured guns in a monument designed as a symbol of national supremacy. Maitland epitomised the heroes the monument celebrated. As a young man, he had sailed in Turkish waters with Nelson and, by a quirk of fate, he had accepted Napoleon’s surrender after Waterloo. For cynics, the later discovery that the bas-reliefs had been illicitly adulterated with other metals and plaster at the foundry proved that even heroes had feet of clay. But for romantics, this fusion of Turkish metal with English stone might have recalled a long-ago story about Nelson and a beautiful Ottoman jewel: his fabled diamond Chelengk. This is that story.

1

THE BATTLE

Aboukir Bay, Egypt, 1 August 1798

They rose in line from the west under a blood-red sky. Thirteen men-of-war falling on their prey. Hood in Zealous found the enemy first, and he now led the way into the uncharted bay, sounding as he went. Nelson hailed his friend from Vanguard, raising his hat in salute.1 In their hunger for prizes, Orion, Audacious, Theseus and Goliath swept past them both.

Weeks of playing blind man’s bluff across the wide Mediterranean Sea – Nelson blind and Bonaparte bluffing – had ended just hours before with the discovery of the French fleet at anchor in Aboukir Bay, at the mouth of the River Nile. With it came the bitter knowledge that the enemy had landed in Egypt. Back in June, the two fleets had sailed within 20 miles of each other, but lacking frigates, Nelson had been unable to probe the sails pricking his distant horizon and Bonaparte had slipped past. To Sir William Hamilton, British envoy to the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies at Naples, Nelson had complained that, ‘‘The Devil’s children have the Devil’s luck’.’2 Hamilton had been feverishly working behind the scenes to push the reluctant King Ferdinand IV of Naples into actively supporting this lone British effort to stem the French tide of conquest across Europe. He was assisted by his beautiful young wife, Emma, who had lavished attention on Nelson on his visit to Naples in 1793. Low born, she wanted to prove her worth to her esteemed husband and to dispel her titillating reputation back in England as an artist’s model, exotic dancer and aristocratic plaything. Together, the Hamiltons had cajoled the King of Naples, terrified of French repercussions, into allowing Nelson to provision and water his ships at Sicily as he hunted down Bonaparte. Without such help, the British fleet could not stay at sea. Rumours of victory or defeat tormented them both. Even as the British warships finally closed on the anchored enemy on 1 August 1798, Sir William was writing to Nelson to express his disappointment that rumours of him ‘having defeated the French fleet in the Bay of Alexandriette on the 30th of June and taken Buonaparte prisoner’ were ill founded.3

Despite the encouragement of the Hamiltons, Nelson was stressed and exhausted; burdened by responsibility and the expectation of a nation on his shoulders. The target of the enemy’s vast battle fleet had been unknown, causing panic across the eastern Mediterranean area from Naples to Malta, Constantinople to Cairo. His officers were also strained, suffering from debilitating ennui in the exhausting heat and drinking heavily at his table day after day. In July, in declining health, Peyton in Defence had pleaded to leave his command altogether, ‘to return to a climate that may give me a possibility of re-establishing it’.4 There was unpleasantness too. At Syracuse, a lieutenant in Orion jumped ship after being accused of importuning a midshipman for sex.5 These were men on the edge.

It was the first time Nelson had commanded a fleet in action, but he did not hesitate now as Vanguard closed with an enemy wrapped in the first shrouds of night. The hundreds of men below him in the gun decks were blind to their fate, their senses sharpened for the smell, taste and feel of battle and focused only on the task ahead. In Goliath, gunner’s mate John Nicol would see nothing of his foe. He recalled only the ominous light of a ‘red and fiery sun’ leaking into the gun deck as they approached.6 All around him, men prepared for battle in the oppressive heat: stripping to the waist, checking guns, opening ports, spreading sand to soak the blood, maybe their own, which would soon flow in warm sticky streams down the deck.

The enemy were well prepared for an attack and yet were still shocked when it came, suddenly and violently from the west. One by one, the British ships snaked through their line – some inside and some without – with brilliant seamanship, anchoring in turn before unleashing murderous fire on their chosen victim at point-blank range. In his haste to join the action, Troubridge turned Culloden into the bay too tightly, thrusting the ship hard into a shoal, where it stuck fast, leaving him to curse and roar at his lost prizes. Ball in Alexander drove into the heart of the enemy line to challenge the towering French flagship L’Orient. Soon a fire was seen licking hungrily in its bowels.

Vanguard was in the thickest action, locked in a deadly slugging match with Le Spartiate. The upper deck was strewn with shattered timbers, shredded sails and torn bodies. Few men exposed to such a maelstrom could escape unscathed, and within an hour Nelson himself was wounded: struck on the head by a piece of red-hot iron which spiralled at him through the heavy air. It slashed through his hat, opening his flesh to reveal brilliant white bone for an instant before blood flooded the wound. His captain, Berry, caught him as he fell. Nelson had been hurt in action before but, stunned, he now feared a fatal injury. His first thought was of Fanny, oblivious and far away in England. ‘I am killed’, he cried out, ‘Remember me to my wife!’7 He was taken below, where the surgeon discovered a ‘wound on the forehead over the right eye. The cranium bared for more than an inch, the wound three inches long.’8 The gash was washed then closed with adhesive strips before the dazed patient was given opium for the searing pain. Nelson was then sat in the bread room below the waterline to recover his dazed senses.

At the heart of the French line, L’Orient was now ablaze from stern to bow, her guns silent and ports burning a fiery chequerboard in the smoke and darkness. Fearing a cataclysm, the nearest British ships pulled away and some of the smaller enemy brigs fled too in panic. Berry went below to find Nelson, leading him back to the quarterdeck to witness the death throes of his enemy’s flagship. From masthead to keel, every ship convulsed and every still-living soul shuddered when L’Orient went up in an eruption of timber, iron, looted treasure and torn, burning flesh. Oblivious to the scene above, John Nicol felt Goliath get ‘such a shake we thought the after part of her had blown up, until the boys told us what it was’.9 Fiery debris, torn limbs and wreckage crashed onto the decks of the nearest ships in a deadly rain of burning embers. Two large timbers ripped from the wooden corpse cartwheeled onto the deck of Swiftsure. The holocaust flooded the battle with bright light, revealing ships locked in mortal combat right across the wide bay.

Nine miles away in Alexandria, French officers listening intently to the rumble of distant battle saw the dreadful explosion on the dark horizon and were troubled by its meaning. Nearer, at Rosetta, others clambered onto roofs to watch L’Orient burn before she blew up ‘with tremendous noise’.10 For several minutes or maybe an hour – shock made memories fluid – the battle stopped, all energy sucked from it by the vortex at its scorching heart. The bay was shrouded by ‘pitchy darkness and a most profound silence’ which the horrified French observers took as ‘a very unfavourable augury’.11 Then, like punch-drunk fighters pulling off the ropes, with rising anger, the opposing ships started firing again, hurling hot iron against each other with renewed fury. Their flagship vaporised, their line shredded, the French fought blindly, crazily, bravely on. In Tonnant, the captain, both legs and an arm shot away, remained on deck, grotesquely and fleshily propped up on a bran tub, his life soaking away. The horror and the exhaustion was so great it was said that entire gun crews, friend and foe alike, fell asleep at their posts during the raging night.12

The battle lurched on sporadically and messily into the next day. As milky dawn broke, firefights still flared across the bay, the now tranquil waters slick with a bloody sheen and broken by wreckage, viscera and bloating dead bodies. Nelson was confused, dazed and disorientated. He lay below decks vomiting, his eyes black from bruising, his head agony and bound with a bloodied bandage. Feverish and irritable, he was enduring the first effects of that severe concussion which would jar his moral compass for months to come, forcing bad decisions and strange behaviour. Weeks of nervous tension had left him weakened and injured but triumphant – and vindicated. He had some hours now to gather his senses and scrambled thoughts: time to compose the perfectly nuanced dispatch for London. He was the master of a good press release. After the Battle of Cape St Vincent just eighteen months before, he had seized the headlines from his commanding officer by leaking accounts of his own boarding of the enemy ship San Josef to the newspapers. But this was a much bigger story and one entirely of his own making. So as he lay in his cot, he started turning phrases in his aching head.

He knew that his daring, the brilliance of his captains – who, with Shakespearean flourish, he now dubbed his ‘Band of Brothers’ - the superb seamanship and gunnery skills of his men, together with the mistakes of the French, had given him victory. He had also been incredibly lucky. His ships had been propelled into Aboukir Bay by a kindly north-westerly on the perfect trajectory for attack, giving the enemy no time to summon men back from the shore. The same wind had also made it difficult (but not impossible) for the rear of the French line, which had escaped, to come to the aid of its centre and van. Not that Nelson ever recognised luck; he called it Providence. With the sounds of occasional gunfire still filtering through the gloomy sweat-heavy deck, he shaped the perfect opening for his dispatch, one which flattered his God, his king and himself. Feeling weak, he called his secretary to his side for dictation, but ‘overcome by the sight of blood and the appearance of the admiral’, he was not up to the task so Nelson took up the pen himself.13 ‘Almighty God’, he wrote, ‘has blessed his Majesty’s Arms in the late Battle by a great victory over the Fleet of the enemy, who I attacked at sunset on the 1st August, off the mouth of the Nile.’ It was said that King George III turned his eyes to heaven with thanks when he read these words some three months later.14 Off Muslim Egypt, a Christian god had vanquished an atheist foe. ‘Almighty God has made me the happy instrument of destruction’, Nelson would tell Emma Hamilton: and that is exactly how he saw it.15 Satisfied, he summoned his officers to a service of thanksgiving on the deck of Vanguard, then ordered his flag captain, Edward Berry, to carry the dispatch in Leander down the Mediterranean to Earl St Vincent, his commander-in-chief at Gibraltar. As insurance against Berry being captured (which he was), duplicate dispatches were sent to Naples with 21-year-old flag lieutenant Thomas Capel in the brig Mutine, with orders to continue overland to England from there. Capel also carried a letter for Sir William Hamilton from Nelson, seeking urgent aid and safe haven for the damaged British ships. Before Capel sailed, Nelson handed him the sword surrendered by the French admiral Blanquet, its blade inscribed VIVRE LIBRE OU MOURIR, for him to present to the Lord Mayor of the City of London when he reached England. Finally, correctly sensing Bonaparte’s wider ambitions, Nelson gave a third letter to Thomas Duval, another young lieutenant in Zealous, to carry to India to warn British interests there of possible attack.

While their commander recovered, his jubilant captains, anticipating their spoils, resolved to form an ‘Egyptian Club’, an instinctive desire in a period when London taverns were crowded with private drinking and dining clubs. Even as the last guns echoed across the bay, they gathered in Orion under a sky wheeling with hungry sea birds and heavy with the stench of death to pledge 80 guineas each for the families of their dead and wounded: 895 casualties in all. They also vowed to pay for a portrait of Nelson, if he survived his wound, and to give him a luxurious gold sword as a memento of their shared victory.16 The idea was Saumarez’s, who envisaged hanging the portrait in an ‘Egyptian Hall’ in London where the captains could meet.17 This giving of gifts was a time-honoured tradition for the victors of battle, a relic from the age of chivalry. So was the hurried grabbing of trophies from this watery battlefield. Captured weapons were traded, and great chunks of L’Orient fished out of the bay and stowed away for crafting into snuff boxes and furniture. Nelson took away L’Orient’s mast head, while Benjamin Hallowell, ‘the gallant but at times eccentric captain of the Swiftsure’,18 gathered enough timber for his ship’s carpenter to make the admiral a coffin so ‘you may be buried in one of your own trophies’.19 Before the completed box left Swiftsure, John Lee, a midshipman in the ship, climbed into it for fun until Hallowell threatened to screw it down and send him with it to Nelson.20

As his jarred senses settled over the coming days and the fear of his own death lifted, Nelson’s strategic grip grew stronger, and with it came the grim reality of his predicament. Hundreds of miles from safety, unfit to sail away, the British fleet was anchored off a hostile coast in a bloody slick of debris and floating corpses which grotesquely defied efforts to sink them with shot. The shoreline for miles around the bay was strewn with masts, rigging, boats and gun carriages which the watching Arabs gathered into huge pyres to burn for the iron.

A more personally pressing matter for Nelson’s officers and his men, discussed by the captains when they met after the battle, was their prize money. This was paid by the Admiralty to the crews of a successful action in return for recycling their captured ships and enemy loot. There now began a lengthy argument over the value of the many Nile prizes, conducted at arm’s length by Nelson through his agent Alexander Davison. Sticking points would be the destruction of L’Orient, for which there could be no payment but which Nelson grumpily thought had £600,000 of treasure stolen from Malta on board when it exploded; and compensation for those enemy ships too damaged to repair, which he had been forced to burn. It was all very irregular, but although the claim for L’Orient was dismissed, in the euphoria of victory the Admiralty did pay out £20,000 for the burnt ships.

As Nelson did his sums, the welcome sight of his missing frigates appeared on the horizon to strengthen his depleted and battle-worn squadron. Less agreeable was the appearance of his stepson, Josiah Nisbet, his wife’s son from her first marriage. Nelson’s patronage had propelled Josiah through the ranks of the navy until he was made commander at just 17. Despite such privilege, Josiah was portrayed as a sullen, obstinate, inattentive and unreliable youth with, in the words of his commanding officer, a love of ‘drink and low company’.21 He was becoming an embarrassment to Nelson. Overlooked was Josiah’s kind nature and obvious bravery, also a debt the admiral knew he could never repay. A year before the Battle of the Nile, Josiah had saved his stepfather’s life during an ill-fated beach attack at Tenerife which had cost Nelson an arm. With presence of mind, Josiah had staunched the bleeding from the wound, applied a tourniquet and evacuated Nelson back to his ship to meet the cold edge of the surgeon’s saw. Now he was in Aboukir Bay, Josiah was yet another awkward problem facing Nelson. (Strangely, Bonaparte was also having to deal with a wayward stepson on this campaign: 17-year-old Eugene Beauharnais, son of his wife Josephine.)

On 17 August, after composing his letters and dispatches with an aching head, making his damaged ships seaworthy, sending his prizes down the Mediterranean (burning the three most damaged with great regret) and leaving Hood in Zealous to blockade the hostile coast, Nelson finally sailed from Egypt. Trusting to Capel’s success at Naples, he headed for Italy to re-provision, take stock and set up a base for operations. Wounded and exhausted, he wanted to go home, but without orders or a clear picture of his strategic situation – his latest mail from London was dated April – he was acting in an information vacuum and forced to improvise. He decided his priority was to bolster the paper-thin blockade of Egypt and keep Bonaparte holed up in Egypt; then, if possible, recover Malta, where the ruling Knights of St John had been recently expelled by the French.

Above all, believing Hood could only remain on blockade until the end of September before running out of supplies, he needed allies. So as Vanguard limped towards Naples, Nelson dispatched Captain Retalick in Bonne Citoyenne to Turkey with a letter for Francis Jackson, the British minister in Constantinople. He calculated that now he was stranded in Egypt, Bonaparte would seek an overland escape route back to France through Syria and Turkey. And so, in the letter he urged the Ottoman government, or Sublime Porte, to confront the French before they reached the gates of the city. The Porte was traditionally friendly towards the French, so in his appeal Nelson tried to stir up antipathy against them. He inflated stories of atrocities in Egypt, part of the rambling Ottoman Empire, by leaking reports that 200 Turks had been massacred at Alexandria in retaliation for his victory at the Nile. Warning that Ottoman Syria would be Bonaparte’s next target, Nelson urged Jackson to press the Porte to send an army to Egypt. Just 10,000 Turks could liberate that country, he suggested, as the French troops were ‘very sickly’ and dying of thirst.22 Or, as he put it more succinctly to Earl St Vincent, ‘If the Grand Signior will but trot an Army into Syria, Bonaparte’s career is over.’23

Nelson wrote to Constantinople more in hope than in expectation. He could not know yet that the aftershocks of his astonishing victory had rippled across Europe, shifting the Rubicon of alliances and age-old enmities. The battle had tipped the Turks, already deeply shocked by the invasion of Egypt, into unlikely alliance with their oldest enemy, the Russians. The Sultan of Turkey had also ordered the Ottoman Governor at Rhodes to send ‘a very abundant supply of fresh provisions, vegetables and most exquisite fruits’ as quickly as possible to Nelson’s starving fleet off Egypt.24 Despite their many historic differences, the new Russian tsar, Paul I, was as unhappy as the Turkish sultan at the spread of French influence in the eastern Mediterranean. Grand Master of the Knights of St John, Paul was also furious at the loss of Malta. Both imperial rulers now dispatched ships to strengthen the blockade of Alexandria and to seize back Malta and the Ionian Islands of Corfu, Zante and Cephalonia. The Portuguese were also sending ships in support. Overnight on 1 August, the whole outlook of the war had changed, making Bonaparte, seen as invincible since his recent victorious campaigns in Italy, suddenly appear vulnerable.

Captain Samuel Hood was an excellent choice for the difficult and stressful task of managing the blockade of the marooned French army in Egypt, as his ship Zealous had escaped relatively unscathed in the recent action. He was also a highly experienced officer, having been at sea almost continuously since the age of 14. The son of a purser, he enjoyed the powerful interest of his admiral cousins: Samuel Hood, Viscount Hood, and Alexander Hood, Viscount Bridport. He was also familiar with these warm waters, having patrolled the Aegean protecting British trade back in 1795. Zealous would cruise the Egyptian coast with Hallowell’s Swiftsure, Goliath, Captain Foley and four frigates: Alcmene, Seahorse, Emerald and La Fortune. Their aim was to pick off prizes, cut out French transports when they could and, above all, to keep Bonaparte locked up in Egypt.

It was stressful work, so Hood was grateful when a ship carrying Selim Agha, ‘a Turkish officer of English extraction’, unexpectedly arrived with welcome news.25 He brought letters from the British embassy in Constantinople and a firman, an imperial order, issued by the Sultan of Turkey granting the British fleet assistance throughout the Ottoman Empire. The agha also carried intriguing rumours, Hood reported to Nelson, that a ‘Hat set with diamonds, indeed they say covered, is preparing for you as a present from the Grand Signior’.26

A month later, on 19 October, the sails of a small squadron of Turkish gunboats and corvettes broke the northern horizon. Ill-prepared for the voyage from Constantinople, the ships were in a sorry state, having endured a month of rough autumn seas with just one compass between them. Their commander, Halil Bey, had been given strict orders by the sultan to make all possible haste to join the British fleet, any delay being met ‘with the severest punishment’.27 Fearing the dire consequences of failure, the bey had pressed on without provisioning properly at Rhodes, leaving his ships nearly out of water and food. On board one of the two corvettes was Kelim Efendi, a genial old scribe from the Sultan of Turkey’s divan, his council of ministers, who had a package for Nelson said to contain the sultan’s precious gift. Described as a sort of ‘head clerk in a secretary of state’s department to us’, Kelim was accompanied by a colourful retinue of attendants.28 These were led by ‘Peter Ritor’, an anglicised Greek who had worked in London as a translator, or ‘dragoman’ (an English corruption of the Turkish tercüman), to Yusuf Agah Efendi, appointed first Ottoman ambassador to Britain in 1793. Officially he was in Egypt to translate for Kelim, but he was probably tasked as well with gathering intelligence for the Porte. He could also probably recognise Nelson. On 27 September 1797, Peter had accompanied the Ottoman ambassador to the king’s levee at St James’s Palace at which Nelson, still suffering the effects of the amputation of his arm, had been invested knight in the Order of the Bath.29

To keep an eye on Ritor, the British embassy in Constantinople sent their own interpreter with the efendi called Bartholomew Pisani. He was Italian and a highly experienced, second-generation dragoman, his father Antonio having been appointed ‘His Majesty’s Translator of the Oriental Languages in Constantinople’ in 1749. Bartholomew had already served the British interest in Turkey for thirty-five years, latterly as chancellor at the embassy, and he would remain a further twenty-five. Like Ritor, he had multiple functions. According to the British minister in Constantinople, he was sent ‘no less to interpret on this mission, than to remain at the admiral’s orders in this theatre of war’.30 It seems Bartholomew brought his son Robert with him on this exciting venture.

Hood was exasperated with all these unexpected, inconvenient guests in their rich flowing robes and tall hats, and he struggled to know what to do with them. ‘He, the Kiélim Effendi, interpreters etc were all dissatisfied with each other,’ he complained.31 Furthermore, ‘the Turks are so very deceitful there is scarce believing anything they say.’32 Unaccustomed to the sea, Kelim was also ill, possibly with scurvy or severe sea-sickness. Conditions in the corvettes were so bad that Hood had the Turks shifted to Zealous, which had a good surgeon on board and, courtesy of the governor of Rhodes, plentiful fresh supplies. The Turkish corvettes were sent away whilst the gunboats were taken into Aboukir Bay to bombard the French shore batteries, each boat having been allocated five British sailors ‘to set a good example’. But the Turks’ gunnery was poor and their courage suspect to prejudiced British eyes. ‘Whenever a shot came whistling from the fort towards the Turks,’ recalled one officer scathingly, ‘they fell down flat on the decks as if shot, and many of them ran below.’33 Others sloped off to smoke their long pipes behind a breakwater. There were also frequent clashes between the Turkish sailors and the British tars, leading to several deaths, and it was only when Captain Hallowell of Swiftsure took charge in person that order and discipline was restored. Hood considered the Turks ‘as horrid a set of allies as ever I had’.34

While Kelim recovered in Zealous, Hood waited for confirmation of Nelson’s safe arrival at Naples. He planned to send the efendi and his precious gift after the admiral in a more robust vessel: one better able to resist the Mediterranean in winter. He was anxious, he told the embassy in Constantinople:

to make this delivery of this ever-memorable acknowledgment of his highness the Grand Signior as conspicuous as possible; but finding this at so late a season of the year I hazarded its delay. The presents shall go with the first frigate or ship of the line, it will be best not to send them in a smaller vessel at this season of the year.35

In the event, Hood was obliged to entertain his exotic guests for a further month before they could continue their journey. Only on 27 November were the Turks finally entered in the books of Alcmene, a 32-gun frigate commanded by Captain George Hope, ‘for passage to Adm Nelson’. The efendi’s attendants and servants were listed as Kalyl, Jimayl, Suleiman, Basyle and Panajot, with the proper name of ‘Peter Ritor’ revealed as Petrarky Rhetorides. The efendi’s full name was phonetically recorded by the ship’s clerk as ‘Mukamed Emior Kelim’, or more properly Muhammad Amir Kelim. Robert Pisani was also added to the muster, having been brought across from another ship, Lion, where he had been quartered and briefed away from prying Turkish eyes.36 Hope sailed the same day with his valuable cargo and a bundle of letters for Nelson, including Hood’s congratulations ‘on the present he will bring you’.37 Yet he could have little idea what awaited him at Naples.

2

THE SULTAN

Constantinople, Turkey, August 1798

The Sultan of Turkey was the first to hear. On 22 August, just three days after Nelson weighed anchor in Aboukir Bay, an enigmatic message was received at Constantinople from the Ottoman Governor of Rhodes, Hassan Bey. A French brig had struggled into his port with the astonishing news that, ‘on the 31 July an English squadron consisting of fourteen ships of the line, one frigate and one corvette had come to attack the French squadron anchored at eboukir (Bequieres), that towards the evening of the same day the English squadron had got into action, and that L’Orient was already on fire, when the captain of the brig came away.’1 This patchy report was onfirmed when Bonne Citoyenne reached Rhodes on 27 August and Captain Retalick went ashore with Nelson’s letter for the British minister at the Sublime Porte. Hassan Bey immediately forwarded it to Constantinople, leaving Retalick to be ‘loaded’ with presents including ‘a very rich and valuable Gold Medal’.2

Writing to the foreign secretary in London from his ramshackle residence in Pera overlooking the glittering Golden Horn, British diplomat (John) Spencer Smith could hardly contain his excitement when he read the letter. ‘I lose not a moment in forwarding homewards by this route what I eagerly conjecture may be the first official report of the glorious news my late letters have so anxiously alluded to,’ he wrote, his pen running fast over the page. ‘I have almost at the same hour received corroborating advices on the subject from Cyprus (dated 22 August), from Aleppo, and from the Porte, whither I am now upon my way, going in consequence of a pressing call.’3

Just 29, Spencer Smith was acting minister to the Sublime Porte whilst London searched for a new ambassador to this sleepy diplomatic posting, the previous appointee Francis Jackson having resigned before even reaching Turkey. Despite his relative youth and inexperience, Smith was about to be thrust into an international crisis. From an impecunious but well-connected family – as a boy he had been a page to George III – Spencer had followed his older brother (William) Sidney Smith into the Royal Navy during the American war. When peace came in 1783, and both boys were placed on half-pay, Sidney began dabbling in freelance intelligence work, while Spencer used an inheritance to purchase a commission in the army. Sidney’s wanderings had taken him to Morocco, where he reported his fears of an invasion of Europe by the Sultan of Turkey; then to Sweden, where he joined the Swedish navy as a mercenary, earning a knighthood from King Gustavus III for his exploits during that country’s war with Russia. Sidney’s foreign decoration was derided by his fellow officers in the Royal Navy, but his value as a fearless freebooting agent was noticed by the British government. The Smith brothers had powerful friends, and as cousins of Prime Minister William Pitt they enjoyed ‘interest’, that essential social currency of the eighteenth century. In December 1793, their father, General Edward Smith, who had held a position in the royal household, had greeted Ottoman ambassador Yusuf Agah to the shores of England. Such connections helped Spencer gain entry to the Levant Company – more popularly known by its earlier title ‘Turkey Company’ – which had enjoyed a monopoly on British trade in the eastern Mediterranean since the sixteenth century.

With war with revolutionary France looming, both Smith brothers travelled to Constantinople. Sidney went to advise the Turkish navy (and to spy for the British) and Spencer, having served an apprenticeship with the Turkey Company in London, to work as a merchant. Within a couple of years, some strings were pulled and Spencer was made secretary to the newly appointed British ambassador to Constantinople, Robert Liston, previously Sidney’s diplomatic handler in Stockholm. In recommending his brother for a career in diplomacy, Sidney, with typical verbosity, described Spencer as ‘particularly qualified for that career by epistolary readiness and talent and adapted to it. His knowledge of the place and study of the Turkish language may be an additional recommendation.’4

Working for the Turkey Company in the Levant – a term for the eastern Mediterranean taken from the French for the ‘rising’ of the sun – had once been highly lucrative for British merchants and diplomats. Relations with their hosts were friendly – Britain had never been at war with the Ottomans – and its royal charter gave the company sweeping tax-raising and political powers, including promoting its own merchants, like Spencer Smith, to diplomat posts in the region. From its factories at Aleppo, Constantinople, Smyrna and Alexandria, the company traded cloth and goods shipped from England for silks and spices in the Orient. But like the Ottoman Empire around it, the company was in long decline, pressed by competition from French and Dutch rivals, changing consumer habits and stifled by its own restrictive practises. By 1792, trade had dwindled so much that the company faced bankruptcy and the Sublime Porte – so called after a fabulous gateway leading to the imperial palace at Constantinople, the Seraglio - was seen as a commercial and political backwater. The outbreak of war in Western Europe appeared to make Turkey even more unimportant, and with enemy warships prowling the Mediterranean preying on their merchantmen, the company’s fortunes declined still further. When Spain then entered the war as an ally of France, the Royal Navy was forced to abandon the Mediterranean altogether, leaving the company’s ships entirely unprotected. Now there were no more than a handful of British merchants still trading at Constantinople, and many of these expressed Jacobin sympathies to curry favour with the dominant French interest. Turkey was so politically disregarded by London that when Liston was transferred to Washington in 1796 and Francis Jackson backed out of the dead-end post, Spencer Smith was placed in charge of the mission as ‘Minister Plenopotentiary’. (That Nelson still sent his Nile dispatch to Jackson shows how difficult it was communicating such news whilst at sea.) Not until 1799 would Lord Elgin arrive as a new British ambassador. Refined and well-connected, Spencer took quickly to his unexpected new role, enjoying the expat social life of the diplomatic quarter at Pera with its balls and whist parties and marrying the beautiful daughter of the Austrian ambassador, Baron d’Herbert.

British lack of interest in the Levant matched the decaying condition of the once-mighty Ottoman Empire. In its heyday, the empire had threatened Western Europe, with Suleiman the Magnificent even laying siege to Vienna. Weak leadership, wars, incompetence and corruption had since forced a slow retreat, yet Ottoman rule still stretched, at least in name, halfway around the Mediterranean, from the Balkans to Libya and beyond. At the heart of the empire, hidden behind the high walls of the Seraglio, his palace in Constantinople, was the Sultan of Turkey, the supreme leader of the Ottomans who could claim descent from the medieval founder of the imperial dynasty, Osman I. The sultan, a mysterious and fearful figure, projected his secular power by firman, mindful always of the authority of the Grand Mufti, the empire’s head of religion, who issued powerful legal and religious opinion through fatwas.

The sultan’s authority was administered by his appointed pashas and their local beys, who controlled the far-flung regions of the empire in his name. Some like Ali Pasha in Albania, Djezzar Pasha at Acre and Ibrahim Bey in Egypt ruled almost like sultans themselves. They paid lip service and a grudging annual tribute to the Porte, but they were unreliable, duplicitous allies and their constant warring further sapped an empire already tagged the ‘sick man of Europe’. Sultans since Suleiman had often been very lazy, very weak or very cruel. All faced plots and coups. The desiccated heads of their enemies and failed ministers, the efendi, decorated the walls of the Seraglio. More recently, a string of disastrous wars with Russia had further exhausted the bankrupt empire of resources and highlighted the woeful and outmoded state of its army and navy. Far from facing these problems, successive sultans had taken the empire further into isolation, turning their back on the technological advances in the west.

The twenty-eighth sultan of the Ottomans was rather different to his forebears. Despite a traditionally sheltered upbringing, Selim III was highly educated, cultivated and liberal minded. He studied and wrote poetry, composed music and, as Sidney Smith observed in 1795, ‘showed greater partiality for the arts than is thought consistent with the system of a strict Musselman’.5 Although his father Mustafa III had been sultan when Selim was born in 1761, the young prince had not been heir to the throne. That precarious position had been occupied by his uncle, Abdu ul-Hamid, as the title always fell to the eldest living male in the ruling Osman family, not by direct descent. Free of this burden, the young prince had been able to explore Constantinople, attend meetings of the divan, his father’s council of ministers, and observe the manoeuvres of the artillery and rifles corps. Romantically inclined and strongly idealistic, he developed a close-knit circle of childhood friends: several of whom became efendis when he ascended the throne. One young companion, Ishak, later made agha, had been present at the Battle of Chesme in 1770 when the Russians had destroyed the once-famed Ottoman navy. This devastating defeat was a formative event for Selim. As sultan, he would seek to reform and rebuild his navy along the lines of the all-powerful Royal Navy, coming to idolise its famous and daring officers. This whimsical and romantic aspect of the idealistic young prince was re-imagined by Lord Byron, who named the tragic hero of his poem ‘The Bride of Abydos’ for Selim. Byron visited Constantinople in 1810 after the sultan’s death and was struck by Selim’s once magnificent gardens, ‘in all the wildness of luxuriant neglect, his fountains waterless and his kiosks defaced but still glittering in their decay’.6

The prince’s relatively carefree life came to abrupt end in 1774 when his father died and his uncle came to the throne. The shy, dreamy boy was now heir to a great empire, and to protect him (and the new sultan) from plots he was hidden away in the innermost sanctum of the Seraglio. Access to the outside world was now strictly controlled, but the prince still managed to conduct a surreptitious correspondence with a handful of, principally French diplomats, intellectuals and physicians. He even exchanged letters with Louis XVI in Paris. France was the traditional ally of the Porte, and there were strong Francophile elements at the Turkish court and within the divan. The sultan was even known throughout Europe by his French sobriquet ‘Grand Seignior’. Britain hardly figured at all.

On 7 April 1789, Selim ascended the throne of an empire again at war with Russia, and now with Austria too. Ottoman losses mounted quickly. The conflict cost the empire the cities of Belgrade and Bucharest, as well as control of the Crimea with its valuable access to the Black Sea. With France consumed by revolution, the Turks signed a treaty with Sweden, which was also fighting the Russians in the Baltic. It was this alliance which brought Sidney and Spencer Smith to Constantinople. The war painfully demonstrated the backward and ramshackle state of the Ottoman armed forces, and when it ended in 1792, Selim launched widespread reforms in his military, which was riddled by corruption, incompetence and nepotism. But he moved slowly and cautiously, as was the Ottoman way. He knew the history of the empire was littered by the bloody corpses of sultans who had acted too rashly. The biggest obstacle to change was the powerful Janissary corps, the imperial bodyguard which enjoyed enormous privilege and was highly reactionary and dangerous.

As sultan, Selim was wrapped in an almost mythical exoticism and strangeness to Western eyes. Invisible to the world, hidden away in the Seraglio with his famed harem of beautiful women (many European), the sultan generated fantastic rumours about his riches, his extravagant tastes, his sexual proclivities and his bloodthirsty appetite. Very few Englishmen entered this magical world, and still fewer women. One who did was Mary Elgin, who accompanied her husband to Constantinople when he eventually replaced Francis Jackson as ambassador in 1799. Raised on tales from the Arabian Nights, first published in English in 1706, Mary was so determined to accompany her husband to the palace that she disguised herself as a man. The procession to the Seraglio was led by 2,000 janissaries, with the foreigners, as was custom, roughly handled all the way. After a huge meal of roasted meats, rose-flavoured sweetmeats and sherbet served in gold dishes, the visitors were ushered by eunuchs into the audience chamber, a small, dimly lit, heavily scented panelled room decorated with bejewelled treasures. In the gloomy midst of all this magnificence, perched on a bed covered with ‘immense large pearls’, was the ‘monster’ himself, Selim III. ‘By him was an inkstand of one mass of large Diamonds,’ reported an awed Mary, ‘on his other side lay his sabre studded all over with Brilliants. In his turban he wore the famous Aigrette, his robe was of yellow satin with black sable, and in the window there were two turbans covered with diamonds.’7 Nothing in the Arabian Nights equalled such opulence. Mary could gaze with wonder at the sultan, but etiquette prevented him from looking at her, or any foreigner. Another privileged English guest to the audience chamber recalled Selim as ‘a man of about forty-three years of age; his beard is become grisly, his countenance is attractive, the tout ensemble of his physiognomy benign; he never lifted his eyes, nor even gave a side glance’.8

The audience with the sultan climaxed with the keenly anticipated exchange of gifts, or douceurs, an essential and timeless Turkish tradition designed to secure mutual interest and obligation. Douceurs were a tool of diplomacy: a projection of status and wealth and a material adhesive for valuable relationships. At an international level, the presents were often stupendously extravagant. During the 1790s, forced to build long-neglected links with foreign courts, Selim had dispatched ambassadors across Europe laden with lavish gifts. When Yusuf Agah arrived as the first Ottoman ambassador in London, he carried with him from Turkey four beautiful horses, a pair of gold pistols and a gold dagger to present to King George III. In addition, Queen Charlotte and her eldest daughter, the Princess Royal, were each given ‘a chest of silks, embroidered with gold; a Plume of Feathers for the headdress, ornamented with diamonds’.9

What presents Lord Elgin should give the sultan on reaching Constantinople had exercised the mandarins at the Foreign Office in London for months. They had been flooded with offers from makers of luxury goods, all eager to supply them. A London representative of the Turkey Company advised that the Turks liked nothing better than English ‘clocks, watches, jewellery, arms, crystal ware and porcelain’.10 They especially loved expensive ‘toys’: small precious objects glittery with gems and glossy with enamelling, often with hidden clockwork mechanisms to surprise the viewer. So Lord Elgin sailed east weighed down by a crystal chandelier, a musical table clock, numerous gold and diamond boxes, watches, rings and pistols. He also packed over 1,300 yards of silks, velvets, brocades and satins to clothe the Turkish court and promote British trade. The total cost of such largesse came to £7,000 (maybe £700,000 today).11

In return, the Elgins received an even more dazzling array of gifts. Mary Elgin was given a diamond ornament to wear in her hair, known as an aigrette, modelled as the 132-gun Ottoman flagship Sultan Selim.12Her husband received a beautiful horse, a traditional diplomatic gift, together with silks, Kashmir shawls, weapons, gems and diamond boxes. With great ceremony, Lord Elgin was also cloaked in a rich fur-lined pelisse, or robe of honour, an integral ritual of such occasions. But all these baubles were as nothing compared to the greater gift Elgin was eventually granted in 1801 when, at the height of his love affair with the British, Selim issued a firman enabling the British ambassador to strip sculptures from the Parthenon at Athens and ship them back to London.

From his spies in Paris, the sultan had heard as early as May 1798, even before their fleet of warships and transports sailed from Toulon, that the French were planning an expedition against Egypt. French officials in Paris and Constantinople vigorously denied the rumours. They were playing for time, hoping that the sultan would come to welcome an invasion of a territory so troublesome to him. Ostensibly governed by an Ottoman pasha, real power in Egypt lay with the Mamelukes, former slaves who over the centuries had forged a powerful ruling elite. Fiercely independent and rebellious, the Mamelukes had caused endless problems for the Porte, forcing an Ottoman expedition to restore order in Egypt as recently as 1768.

Napoleon Bonaparte, the dashing young general who led the French force, convinced himself he was helping the Turks, dressing up his invasion as a liberation from Mameluke tyranny in a series of impassioned letters to the Porte. He also sent the sultan a diamond ring set with a miniature of himself in an act of brotherly friendship. However, the real aim of the Directory in Paris appeared to be to threaten British interests in India (and to keep France at war abroad to suppress dissent at home). Securing an overland route to the Far East would disrupt trade and pave a way for a full invasion of India, the jewel in the British crown. French overtures were already being made to Tipu Sultan, the Tiger of Mysore, to form an alliance to help drive the British out of India. Despite these wider strategic goals, Bonaparte also wanted to explore, map and catalogue the hidden treasures of Egypt. It was said he dreamed of creating an enlightened new Islamic state in the spirit of the French and American revolutions. He even studied the Koran on the voyage out, appearing at breakfast in his flagship L’Orient in turban and robes and vowing to convert to Islam when he had conquered Egypt. Propelled by this vision and a burning personal ambition, Bonaparte evaded Nelson’s warships in the Mediterranean before landing in Egypt unopposed on 1 July. After routing the Mamelukes at the Battle of the Pyramids, he installed himself in a palace in Cairo, in confident expectation of the grateful thanks of the sultan. Instead, on 13 August, he heard that his fleet, his lifeline to Europe, had been destroyed by Nelson at Aboukir Bay, near Alexandria. Badly shaken, Bonaparte was philosophical about this disaster. ‘So, we are now obliged to accomplish great things,’ he told his crestfallen officers, ‘and accomplish them we will.’13 He still expected the sultan to accept his occupation of Egypt, and took comfort from a promise made by French foreign minister Charles Tallyrand that he would travel in person to the Porte to sell the invasion to the Turks. But, unknown to Bonaparte, the Machiavellian Tallyrand had stayed in Paris, hoping and expecting his rival would die in the sands of Africa.

The invasion of Egypt placed Selim in a quandary. French diplomats in Constantinople had repeatedly assured him, possibly believing it themselves, that the real target of the massed French fleet was far-off England. When the invasion, and their deceit, was confirmed, they trusted to old ties of friendship to protect them. The attack on Egypt was a gross violation of Ottoman territory, but France was also the Porte’s closest ally, supplying vital military expertise and equipment during Turkey’s recent wars with Russia. The decapitation of the King of France had alarmed Selim – as it did every crowned head in Europe – but he was known to be in sympathy with many of the intellectual aims of the revolutionaries. They had been welcomed at Constantinople, where they wore tricolour cockades openly in the streets and, to the horror of a British patriot like Spencer Smith, had planted a Tree of Liberty outside the French embassy.

With public feeling in Turkey running high, the Grand Mufti issued a fatwa authorising holy war against France. Yet still Selim hesitated to act, handicapped by his Francophile ministers and the caution of his precarious position. He restricted French access to the Seraglio, but little else. Less constrained, Spencer Smith worked feverishly behind the scenes to stir up trouble for the French. He proposed an unheard-of alliance between Britain, the Porte and its old nemesis Russia to fight the now common enemy. The sultan acknowledged this radical idea, issued a firman granting the British fleet assistance in the Levant, but still bided his time on ratifying the treaty. Yet Smith was confident of winning him over. Writing to Nelson just two days before the Battle of the Nile, he reported that the shock in Constantinople at the invasion of Egypt had ‘matured into positive enmity’ against the French.14

Then everything changed. On 16 August, a week after sailing from the shambles in Aboukir Bay in a local dhow laden with beans, Lieutenant Thomas Duval of Vanguard, Nelson’s dispatch safely tucked in his coat, reached Scanderoon, now .Iskenderun, near Aleppo in Syria, ‘a little paltry place, in the midst of a swamp’. Here Duval ‘delighted’ the Turkish governor with news of the victory before forwarding it by letter to the British consul at Cyprus. Then, after swapping his uniform for Arab robes and hiring camels and guards, the intrepid Duval continued overland to India. With the Red Sea in enemy hands, he headed out across the desert to Baghdad, where the ecstatic Ottoman pasha ordered him back into uniform and, despite the scorching heat, clothed him in a robe of honour. He then gifted Duval a boat to carry him down the Tigris to the Persian Gulf, where a sloop met him for the voyage to India.15 Finally, on 21 October 1798, just ten weeks after leaving Nelson, Duval reached Bombay and a hero’s welcome from the embattled British community.

Duval’s epic journey lit a fire across the Levant. His news confirmed the report from Rhodes and finally pushed Selim into decisive action. He issued a firman declaring war against ‘those faithless brutes the French’.16 ‘God be praised,’ he scribbled on the report of the battle, ‘I am pleased. God willing, may they all be damned. Make it known to the British ambassador.’17 The sultan’s Francophile Grand Vizir, his prime minister, was instantly sacked and, lucky to keep his head, thrown into a prison with the French ambassador and his staff. ‘The Rubicon is happily passed,’ declared a triumphant Spencer Smith, who now received Nelson’s triumphant dispatch addressed to Francis Jackson. Within days, Smith’s proposed treaty between the Ottoman Empire, Russia and Britain was confirmed. Russian warships started arriving in the Bosphorus, with Russian admiral Feodor Ushakov going ashore to discuss joint operations against the French with the Capitan Pasha, head of the Ottoman navy. Remarkably, Selim then made a surprise visit to the Russian flagship himself. The highly decorated Russian admiral had been the scourge of the sultan’s navy during the recent conflict between their countries, but now he was warmly welcomed to Constantinople and presented with a ‘snuff box richly set with diamonds’.18 It was agreed that an Ottoman fleet under Turkish admiral Abdul Cadir Bey would join with the Russians to expel the French from the Adriatic, where they occupied the Ionian Islands of Zante, Corfu and Cephalonia threatening an invasion of the Balkans. A smaller force of tenders, corvettes and gun boats would sail in support of the British blockade of Egypt, with the Porte favouring Nelson’s idea of a land campaign through Syria to liberate Egypt rather than a landing by sea.

Spencer was delighted, watching as the hated Tree of Liberty was uprooted and his rival French merchants and diplomats rounded up and interned. He was now at the centre of things: meeting the sultan’s ministers, going aboard the Russian flagship to meet Ushakov in person and, above all, bursting with ‘an honest pride that HM’S mission has not been backward in keeping pace with the gallant admiral on Terra firma’.19 He then heard he would be joined in his diplomatic mission by his brother, who was returning to Turkey. Back in London, fame and favour had combined to make Sidney Smith not only joint minister in Constantinople but also commander of all British naval forces in the Levant.

The sultan was captivated by the exploits of Nelson at the Nile and wanted to reward him in traditional Ottoman style. The day after the British victory was confirmed, the sultan personally ordered a ‘fine fur and a superior çelenk’ to be sent out to the admiral.20 The reward of a çelenk – phonetically ‘Chelengk’ in English – for bravery on the field of battle was a long-established Ottoman custom. Usually a simple turban ornament cut from a silver plate, unadorned with gemstones and crested with three, five or seven plumes, depending on the award; for Nelson Selim selected a deluxe version from his personal treasury, one smothered in diamonds. Rumours that the sultan was sending presents to Nelson washed around the diplomatic quarter at Pera for days before Spencer Smith was told officially during an audience with the Ottoman foreign minister on 8 September. Smith had taken an Arabic translation of Nelson’s Nile dispatch to the meeting, together with an explanatory sketch of the action, ‘such as my experience taught me to be necessary for a nation of beings who judge only by the senses’. Whilst poring over the drawing, the ministers were interrupted ‘in a dramatic way’ by a messenger carrying a parcel from the sultan.21 The courier produced a flowery letter of congratulation addressed to ‘our much esteemed Friend Admiral Nelson’ which promised 2,000 sequins for the men who had ‘bled’ at the Nile. As a sequin – a small gold coin used throughout the Levant – was worth 9 shillings, the bounty was estimated at about £900 (or £80,000 today). British casualties at the battle were 218 killed and 677 wounded, so assuming the sultan intended the money for the injured survivors only, each man would receive £1 6s 5d. However, it is not known whether, when or how this money was ever distributed.22 Hearing that women were also present in the British ships during the action, ferrying water to the gun crews and attending the wounded, Selim sent them presents too, although at least two had since died of wounds (and a third given premature birth in shock).23

In his excited letter to London reporting the meeting, Spencer described how the messenger had then taken from his parcel:

a superb aigrette (of which the marginal sketch gives but a very imperfect idea) called a Chelengk, or Plume of Triumph, such as have been upon very famous and memorable successes of the Ottoman arms conferred upon victorious (Musselman) Seraskers (I believe never before upon a disbeliever) as the ne plus ultra of personal honour as separate from official dignity.

It was indeed a most extraordinary and luxurious object, far more exotic, unusual and precious than other Chelengks Spencer must have seen before in Constantinople. It was whispered in diplomatic circles that the jewel had been taken personally by the sultan from one of his own turbans and was worth almost £1,000 (perhaps £100,000 today). Next, the messenger unwrapped a magnificent red robe of honour lined with sable fur ‘of the first quality worn at this court’, valued at a further 5,000 dollars. Finally, there was a diamond box ‘of the usual ministerial kind’ for Smith himself.24 The messenger asked Smith to seek royal permission in England for Nelson to wear the Chelengk ‘on his joyous head and to put on the fur’.25

Smith was struck ‘dumb’ when the presents were revealed:

I did, however, at last contrive to find words to thank the Grand Signior in the name of the King my master; in that of my valiant fellow subjects; of his Majesty’s ministers; and on my own account.

Familiar with Ottoman culture and its tradition of present-giving, Smith saw at once the exceptional nature of the sultan’s gifts, explaining to his superiors back in London that, ‘it can hardly according to the ideas annexed to such insignia here be considered as less than equivalent to the first order of Chivalry in Christendom.’ Seeing the Chelengk as a military decoration comparable to the British Order of the Bath would make it easier for the king to agree, Smith conjectured, ‘for the admiral’s wearing the Chelengk upon his cockade’.26