9,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

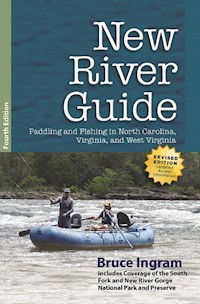

- Herausgeber: Secant Publishing

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Fourth Edition (2022) - with Updated and Expanded Content

Includes coverage of the South Fork and New River Gorge National Park and Preserve

The New River is one of the most changeable and fickle rivers on the East Coast and also one of the most beautiful and rewarding.

It attracts anglers, canoeists, kayakers, rafters, bird watchers, rock climbers, and those who simply enjoy the great outdoors.

The New River Guide provides an indispensable overview of this untamed and scenic waterway as it winds through three states, including the bucolic South Fork in North Carolina, the ridges of Virginia, and the gorges of West Virginia.

Both casual and hardcore anglers will learn of the best places to fish for smallmouth bass. Canoeists will find the most enticing sections to paddle, whether they prefer placid stretches or white water. Rafters and kayakers headed for Class IV rapids in the New River Gorge will find The New River Guide a must-read.

This new edition for 2015 includes updated and expanded information on favorite float trips, fishing spots, access points, bass lines and lures, and river guides and other resources.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 325

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Copyright © 2014, 2022 by Bruce Ingram All rights reserved.New River Guide, Fourth Edition

Secant Publishing, LLC615 N. Pinehurst Ave.Salisbury, MD 21801SecantPublishing.com

Reproduction in any manner, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of the publisher is prohibited with the exception of small quotes for book reviews.

The chapter entitled “Casting for Recovery … Literally,” appeared first in Virginia Wildlife, the official magazine of the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources.

Every effort was made to make this book as accurate and up to date as possible. However, there are no warranties, expressed or implied, that the information is suitable to any particular purpose. The maps are to suggest river structure, but are subject to frequent change. The author and publisher assume no responsibility for activities in the river corridor.

ISBN: 979-8-9851489-4-7 ISBN (epub) 978-0-9907833-4-3

Photography by Bruce IngramCover, interior, and eBook conversion by Rebecca Finkel, F + P Graphic Design, FPGD.com

To my best friend and wife, Elaine,

who proofread the entire book

and who is a wonderful wife, mother,

and schoolteacher.

Also to my daughter Sarah and my son Mark—in your lifetime, may you come to love the outdoors like I do.

The New’s New Designation

In late December of 2020, the United States Congress passed legislation that established the New River Gorge National Park and Preserve in Fayette and Raleigh counties. Thus, the Gorge became the 63rd National Park and the 20th National Preserve in our country. The new designation results in a 65,165-acre preserve where hunting and fishing will be allowed and a 7,021-acre park. Another plus is that the National Park System will be allowed to bid on additional land to add to the Gorge. I have hunted, fished, rafted, and birded in the Gorge since 1987 and see the designation as a way of bringing national recognition to the area.

Britt Stoudenmire, who operates the New River Outdoor Company, favors the new designation.

“The New River Gorge is a special place in so many ways and the new designation just adds to that,” he said. “The New is the second oldest river in the world, and it is quite probably the most remote gorge in the East. The high country mountains and the wilderness setting make you think you’re somewhere out West.

“With the national park and preserve designation, I think you’ll see people from all over the country come here. Many folks take pride in visiting all of the national preserves and national parks. Frankly, the Gorge has always been a bucket list destination for fishermen and white water paddlers.”

Stoudenmire also has praise for the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources (DNR). He especially likes the 12-mile catch-and-release section from the I-64 Bridge at Sandstone to the park service’s Grandview Sandbar access site near Quinnimont.

“Over the years, the DNR has done an excellent job of managing the New’s smallmouth fishery and the fishery in general,” he continued. “The new designation will bring more awareness of the fishery resource and more people fishing the river. Having a catch-and-release section will help protect the fishery.”

The new designation won’t change the fact that the New River Gorge remains a dangerous place for those anglers and paddlers who like do-it-yourself experiences. The Gorge is no place for beginning and intermediate canoeists, kayakers, and other paddlers. Indeed, every year expert paddlers perish here. The river is best experienced by folks going with professional rafters, Stoudenmire emphasizes. Even the upper reaches of the Gorge flaunts dangerous drops like Brooks Falls. On many waterways, the word falls is often just another name for a rapid. However, on West Virginia’s New, falls are life-threatening rapids best portaged or, again, experienced with a professional rafter.

“Many people have no idea of the force that exists in Class IV and bigger rapids,” Stoudenmire said. “The waves are so intense. And the sheer, heavily forested canyon-like walls that surround much of the river make rescue difficult. Cell reception is poor as well. Again, people should experience the river with a professional.”

Those Class IV and above rapids also cause anglers to have to fish the river differently.

“You can fish Class I and II rapids on the average river,” Stoudenmire said. “But on the New, you don’t fish those major rapids, you fish the pools between them. You also have to often fish rapidly retrieved lures such as grubs, buzzbaits, and various topwaters. Fly fishermen often use streamers.”

Stoudenmire encourages outdoors folks to visit the Gorge and celebrate the new designation.

“Just being in the Gorge is an unbelievable experience,” he said. “It’s like stepping back into the past to an earlier time when the country was largely unsettled.”

—Bruce Ingram

Preface

Introduction

Section One:Recreation Opportunities

Classic Warm Water River Smallmouth Patterns

Falling for the New’s Autumn Smallmouths

Winter Wade Fishing with Crayfish Patterns and Lures

The Adventure of Fishing for Whitewater Smallmouths

The Adventure of Whitewater Rafting

Your Best Fishing Buddy Can Be Your Own Child

Birding by Boat

Jerkbaits: the Essential Spring Lures for Black Bass

Casting for Recovery…Literally

Making Sense of Modern Line Types

Floating and Fishing the South Fork of the New

Conservation Groups on the New River Watershed

Section Two: The New River above Claytor Lake

Confluence to Riverside map

1 Confluence to Mouth of Wilson

2 Mouth of Wilson to Bridle Creek

3 Bridle Creek to Independence

4 Independence to Baywood

5 Baywood to Riverside

Riverside to Buck Dam (Fowler’s Ferry) map

6 Riverside to Oldtown

7 Oldtown to Fries Dam

8 Fries to Byllesby Reservoir

9 Byllesby Dam to Buck Dam (Fowler’s Ferry) 96

Buck Dam (Fowler’s Ferry) to Allisonia map

10 Buck Dam (Fowler’s Ferry) to Austinville

11 Austinville to Jackson Ferry (Foster Falls)

12 Jackson Ferry (Foster Falls) to Allisonia

Section Three: The New River below Claytor Lake Dam to Bluestone Lake

Claytor Lake Dam to Backwaters of Bluestone Lake map

13 Claytor Lake Dam to Bisset Park

14 Bisset Park to Peppers Ferry Bridge

15 Peppers Ferry Bridge to Whitethorne

16 Whitethorne to McCoy Falls (Big Falls)

17 McCoy Falls (Big Falls) to Eggleston

18 Eggleston to Pembroke

19 Pembroke to Ripplemead

Ripplemead to Mouth of Indian Creek map

20 Ripplemead to Bluff City

21 Bluff City to Rich Creek

22 Rich Creek to Glen Lyn

23 Glen Lyn to Shanklins Ferry

24 Shanklins Ferry to Mouth of Indian Creek

Section Four: The New River below Bluestone Lake Dam to Fayette Station

Bluestone Dam to Glade Creek map

25 Bluestone Dam to Brooks Falls

26 Below Brooks Falls to Sandstone Falls

27 Below Sandstone Falls to Glade Creek

Glade Creek to Thurmond map

28 Glade Creek to McCreery

29 McCreery to Thurmond

Thurmond to Fayette Station map

30 Thurmond to Fayette Station

Appendix A: Plan Your Trip: Contacts, Outfitters, Maps

Appendix B: Birds of the New

One of the great blessings of my life is to have been born and reared between the James and New Rivers in southwest Virginia. I have lived my entire life in the cradle they form. The two streams have always spoken to my sporting soul, so much so that I wrote a book on the former, the James River Guide, and have now penned one on the latter.

Although the two waterways are very close to each other in proximity (less than a ninety-minute drive in places) the James and New are extremely different in personality. Whereas the James for the most part flows through forests, fields, and rural surroundings, the New courses through small hamlets and towns as well as isolated forests and spectacular mountain gorges. The James meanders at a moderate pace throughout the majority of its length with just enough Class I and II rapids sprinkled along the way to keep matters interesting. The New, however, does virtually nothing in moderation. Throughout North Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia, strong Class II and III rapids punctuate the streambed, and in places, specifically in the Mountain State, Class IV+ rapids are the norm. And just about everywhere one goes on the New, a considerable undercurrent exists as the water of the New always seems to be in a hurry to join with the Gauley, which forms the Kanawha, and then on to the Ohio and Mississippi.

Although both rivers are nationally known among those who enjoy the outdoors, the New deservedly has the greater renown. Canoeists and anglers primarily visit the James, whereas the New attracts those two categories of outdoorsmen as well as rafters, kayakers, rock climbers, bird watchers, and a host of other outdoor enthusiasts from across the country. Also, the New often has two statements repeatedly made about it. The first is that it is the second oldest river in the world next to the Nile, and the second is that the New is one of the few rivers that flow north. Actually, both statements are usually made by those who do not know much about the area. Yes, the New is incredibly old and has been reputed to be anywhere from ten million to three hundred and sixty million years of age. But is only the Nile older, who really knows? As far as being one of the few streams that travels northward, the New is not the only river in the area that flows north. The South and North Forks of the Shenandoah, in Virginia, are rivers fairly close to the New that run northward, but few people make statements about the rarity of their directional paths.

For ease of reference, I have divided this book into four sections. Fly and spin fishermen as well as canoeists, rafters, and bird watchers will hopefully find Section 1 filled with enough how-to tips to make their time spent on the New more enjoyable. The three where-to sections of the New follow:

Section Two:The New River above Claytor Lake

Section Three: The New River below Claytor Lake Dam to Bluestone Lake

Section Four: The New River below Bluestone Lake Dam to Fayette Station

River runners will find these divisions useful if they plan to make extended excursions down the waterway.

Readers should realize that the New, more than many rivers, is a highly changeable waterway. I like to say that the James is comparable to the steady girlfriend who a guy can always count on to be by his side. The New is more like the fickle temptress who is a bit of a shrew and always changes her mind. The information I have presented is the most up to date at the time of publication, but the New’s inconstant state, as well as floods and other natural phenomenon can increase or decrease the strength of a rapid as well as alter landmarks. Access points also sometimes change over the course of time. Be sure to check with the outfitters mentioned in the appendix before planning a trip.

I relish my time fishing, canoeing, rafting, and bird watching on the New River. I hope you will come to love this river as I do.

—Bruce Ingram

Classic Warm Water River Smallmouth Patterns

Falling for the New’s Autumn Smallmouths

Winter Wade Fishing with Crayfish Patterns and Lures

The Adventure of Fishing for Whitewater Smallmouths

The Adventure of Whitewater Rafting

Your Best Fishing Buddy Can Be Your Own Child

Birding by Boat

Jerkbaits: the Essential Spring Lures for Black Bass

Casting for Recovery…Literally

Making Sense of Modern Line Types

Floating and Fishing the South Fork of the New

Conservation Groups on the New River Watershed

Whenever I receive accounts of river anglers catching dozens of smallmouths on a day trip, I have to groan. For invariably, those same reports conclude that the fish were mostly “dinks” and that the particular river visited is overpopulated with undersized smallies. I live in Southwest Virginia, and my home is less than an hour’s drive from the James River to the north and the New River to the south, two of the finest smallmouth streams in the country. A group of four or five friends and I regularly journey to this duo, and we never catch dozens of fish. Our goal is simple: one keeper “bite” (a strike from a fish fourteen inches or better) per person per hour. All of us annually catch smallmouths in the four-pound plus range, which are trophies anywhere in the country for river bronzebacks. The key to this approach is recognizing the few areas in a stream that actually harbor good-sized fish and then employing the proper lures. Here, then, are six patterns that produce “bites” from spring through fall.

The Deep-Water Ledge and Soft Plastics Pattern/Weighted Streamer

One of my favorite spots on the James River is a massive deep-water ledge that extends some ninety yards in length and some thirty yards in width. This bass sanctuary is well away from both banks. Although it lies in the middle of one of the most heavily fished sections overall of the James, I have never seen anyone work it.

Therein lies part of the appeal of deep-water ledges. They are often far away from the shoreline, and their deep water (this particular ledge features depths of six to fourteen feet) discourages the average fisherman from even considering a cast. Ledges are also home to numerous prey species of smallmouths; crayfish especially dwell in the crevices and rubble that exist in the bowels of this structure. The crawfish factor makes soft plastic imitations of ’dads a superlative bait for ledges. I like to rig my craws with 3⁄8-ounce bullet sinkers. This better enables them to descend into the depths and to stay there, thus overcoming the pull of a river’s current.

On one trip down the James, I used crayfish baits to probe the aforementioned ledge for about thirty minutes as my canoe drifted lazily along. Although I caught several nice fish, I knew the ledge held higher quality bass. To give the fish a different look, I switched to a six-inch plastic worm and worked the area again. I caught a two-pounder and missed another fish of that size. Plastic lizards and Carolina-rigged grubs are other baits that can be used after you first check out the ledge/crawfish pattern. Fly fisherman can employ weighted streamers, nymphs, and crayfish

The Eddy and Crankbait/Spinnerbait/Clouser Minnow Pattern

By definition, an eddy is an area where the “current runs contrary to the main current,” or reverses back upon itself like a whirlpool. Because of an eddy’s nature, minnows especially become trapped inside as do a number of other forage species. Eddies are favorite hunting grounds of smallmouths and any mossyback found within will be actively engaged in tracking down prey. As such, eddies are ideal places to cast lures such as crankbaits and spinnerbaits, and flies such as Clouser streamers which can be rapidly retrieved.

Inside tip: Tie on the same ½- to 1-ounce tandem willowleaf spinnerbaits that you do for lake largemouths. These larger blade baits will work better in the heavy current of eddies and attract larger fish, as well.

During a late spring cold front last year, a friend and I failed to find fish at most of our favorite places. The only areas that did generate action were eddies, and interestingly, the mossybacks eagerly whacked crankbaits as if the conditions were entirely favorable. I scored by erratically retrieving Storm Wiggle Warts across rocks; most strikes occurred when the bait glanced off this form of cover. Sometimes in eddies, spinnerbaits will out-produce crankbaits.

The Current Break and Grub Pattern

I know a West Virginian who fishes nothing but the current break/grub pattern from spring through fall. He totes along a brown paper bag filled with three-inch motor oil grubs and ¼- to 3⁄8-ounce jigheads. His best Mountain State smallie topped six pounds and goodness knows how many four- and five-pounders he has derricked aboard. I don’t restrict myself just to grubs in motor oil but I do recognize the bass-holding potential of current breaks. Current breaks come in several forms, but the best example is a midstream boulder that is partially submerged. Over time, the force of the water tends to hollow out the water behind a boulder giving smallmouths the greater water depth that they so crave. Those same depressions and the rocks also provide bass with ambush points from which they can lash out at minnows, hellgrammites, and other creatures that drift by. Indeed, these creatures themselves often seek out the slack water behind boulders and end up being consumed there.

Laydown logs are another excellent example of current breaks. Often trees, such as sycamores and silver maples, tumble into a river after the current has washed away a section of the bank. Once these trees come to rest on the bottom, they provide superlative cover and, just like midstream boulders, a refuge for bronzebacks looking to escape the main force of the current. The rubble from old dams and the supports of bridges are other examples of current breaks. On the James, one of my favorite current breaks is a partially submerged station wagon that was washed into the river during a flood several years ago. Current breaks can take many forms and they all can conceal overgrown bronzebacks.

The Grass Bed and Buzzbait Pattern

Back in the 1990s, I was fishing the upper Potomac with a guide. The time was mid-July and although he and I had done well early in the day, the fishing had slowed considerably. To my surprise, the guide maneuvered his jet boat to within casting distance of a grass bed and then began flinging a buzzbait to the edges of the grass. I considered the first two-pounder that the gent caught a fluke, and I became only mildly interested when a second fish lunged at the bait. When another two-pounder crushed this blade bait, I begged him for his buzzbait and today that same lure has an honored place in my tackle box and has produced dozens of jumbo smallies, as have a series of other buzzbaits that I now own. I am not going to attempt to analyze why river smallmouths become so riled when they see a buzzbait churning by them. But I do know that no other bait will entice fish lurking around vegetation like this one does. If you want to maximize the grass bed/buzzbait pattern, learn to recognize the areas where bass are most likely to hold along this cover.

For example, the ideal situation is one where the downstream side of a bed has a drop-off that is at least a foot deeper than any of the water depths at the sides or the upstream side of the vegetation. Smallmouths will lie in this drop-off when they are inactive, but will move up to the edge of the grass when they are ready to feed. And one of the surest bets in river fishing is that an active grass bed bass will crunch a buzzer.

Another super situation is an isolated patch of grass with deep water on at least one of its sides. This type of condition usually occurs when spring floods have washed away part of a small island where vegetation once thrived. Finally, any time the main channel of a river winds its way close to a grass bed, consider a buzzbait. The grass bed/buzzbait pattern will yield smallmouths throughout the day from late spring through early fall.

The New River offers outstanding warm water smallmouth sport.

I also want to add one tidbit about buzzbaits. Many anglers swear that the color of a buzzbait makes a difference. I disagree. The buzzbait is a pure reaction lure, the color could be pink with orange stripes and it would not matter to the fish.

The Jig and Pig Pattern Fished Deep or Shallow: An All-Season, All-Purpose Big River Bass Pattern

The best river smallmouth anglers I know all heavily rely on the jig and pig throughout the year. For example, one summer during an excursion down the James, a friend caught and released twenty-two keepers on this bait. His game plan was to cast a 1⁄8-ounce homemade hair jig tipped with a tiny plastic crayfish trailer to current breaks. On a trip one fall, two of my friends used a ¼-ounce jig and Zoom Salt Chunk to catch a number of fine smallies in the two-pound range. They targeted shoreline cuts with laydown logs. One winter, I entered a river smallmouth tournament and, you guessed it, anglers using jigs with pork trailers produced all the top catches. The preceding year, my best spring smallmouth, a four-pounder, fell to a ½-ounce jig with a pork trailer. That smallmouth came from a submerged logjam in an eddy. In short, you can employ the jig and pig as the main lure for any of the hot spots in the aforementioned patterns. Some anglers prefer hair jigs, while others opt for homemade versions made from a variety of compounds. Still others like the synthetic models on the market today. Some anglers select soft plastic trailers, while others go for the traditional pig. No matter, the jig and pig is a necessary bait for the serious river angler. This book won’t help you catch a hundred fish per day, as so many river anglers like to do. But the patterns mentioned can lead to you catching more high-quality brown bass.

The Damsel and Dragonflies Pattern of Blane Chocklett: Great for Warm Water

During the warm water season, two of the favorite foods of stream smallmouths are also two of the hardest patterns for fly fishermen to create: the damsel and dragonflies. For years, guide Blane Chocklett was frustrated by this fact.

“I didn’t like any of the damsel or dragonfly imitations on the market,” he recalls. “Some of them didn’t float well, some weren’t durable, and some didn’t look like the real things. So one day, I was sitting at my bench and braiding some material, and I thought that if I could use this material to create the body of a damsel fly, it would look really nice.”

After the concept occurred to him, Chocklett says it was simple to flesh out the wings and the rest of the fly. Indeed, with their shimmering blues, greens, and yellows, the Roanoker’s creations are quite striking—the most true-to-life Odonata imitations that this writer has seen. Chocklett suggests that long rodders cast his damsel and dragonflies to water willow beds, undercut banks, and at the head and tail ends of pools. Interestingly, Chocklett says his flies have a bass-bewitching, undulating motion when they are slowly twitched, a trait that makes them good choices for riffles.

Some four hundred damsel and dragonfly species exist in North America, and scores thrive along rivers. Blane Chocklett can’t fashion patterns to match all those species, but he has made a fine start on duplicating the appearance of several that live in the Southeast.

Positioning our boat within casting distance of a series of laydowns in six to eight feet of water, my buddy and I began working ½-ounce jig and pigs around the wood. On my fifth cast to the heavy cover, I received a strike and I used a medium-heavy baitcaster (spooled with 14-pound-test line) to derrick the four-pound bass from the cover.

Scenes like this occur every autumn across America on the country’s best largemouth lakes as the fish become more active after experiencing the summer doldrums. My friend and I weren’t on an impoundment, however. We were in a canoe and fishing for river smallmouths. The typical river smallmouth story line details how an angler “employs small baits, light line, and light action rods for these feisty little fighters that inhabit the swift moving, shallow sections of streams.” If you are interested in catching dozens of eight- to ten-inch smallies, then this approach is quite sound. But if you want larger river bronzebacks this autumn, you need to fish like impoundment fishermen do when they go after bigger bass. Fish the same locations with the same types of lures that they use.

Where to Find the Big Ones

Certain types of lairs attract overgrown river smallmouths throughout the fall. One of my favorite places is the tail end of a pool below a rapid. During the summer, smallies are more likely to hold where the rapid first breaks into the pool. But by the fall, as the water temperature decreases, the fish tend to go farther away from the swift water and set up.

Another likely locale is a relatively deep pool along a shaded outside bend. Even with the water temperature lower now, smallmouths still seem to retain their penchant to ambush prey from shaded lairs. Bass tend to avoid full sun areas except during the winter and early spring.

Several other big smallmouth honey holes are also worth mentioning. One is a series of deep-water ledges that rest in water at least six feet deep. Sometimes, the top of the ledge may even be visible above the surface. This type of spot is such a sweet one in the fall because of the deep water between these ledges. Numerous prey species (crayfish, minnows, sculpins, mad toms, and various aquatic insects) frequent the nooks and crannies of these ledges and overgrown smallmouths do, as well.

Another marvelous location is a bank with numerous cuts or indentations along its shoreline; that is, if those cuts contain underwater logs and water five or more feet deep. Many river fishermen don’t associate wood with smallmouths, and they are correct to the point that few smallies actually hold around wood. But a log in deep water will often harbor a two-, three-, or even a four-pound mossyback and such cover is well worth checking out. During the fall, a deep-water laydown pattern will produce throughout the day. Focus on logs that are at least partially in the shade. Generously endowed mossybacks wait there in ambush.

Another consistent locale is a deep-water pool. Barry Loupe, another outstanding fisherman, maintains that a deep pool with a rapid at its head can attract large smallies, especially in early to mid-fall. Look for the smallmouths to periodically move into eddies on the sides of that pool where they will dine on creatures that have been washed into and trapped in the reversing currents there. Indeed, both Loupe and I agree, the only time to fish thin water for good-sized river smallmouths is very early on a warm autumn day when the nicer fish have temporarily moved shallow before the sun rises.

How to Catch the Big Ones

One of my favorite fall baits is a little bit of a surprise, a Rebel Pop-R. As long as the water temperature falls no lower than the upper 50s, a topwater bite will exist. It won’t be as predictable or as long as the one that occurs from late spring through summer, but it will happen. I am more likely to let the popper drift along than give it violent jerks.

Another great choice is a soft plastic jerkbait. I prefer the four-inch size because it is the size of large minnows and small chubs this time of year. Let the jerkbait fall slowly to the bottom and give it a gentle twitch every now and then.

Barry Loupe says that his preferred bait on the New River and the North Fork of the Holston where he lives is a lake angler’s favorite: the venerable jig and pig. Loupe belongs to a river fishing bass club that holds tournaments on the North Fork. In a recent year, some 90 percent of the anglers who won the big smallmouth prize for those events were fishing a jig and pig. “Another terrific artificial,” continues the guide, “is a six-inch finesse worm.” Loupe and a friend together caught twelve smallmouths of twenty inches or longer on this bait during a recent six-month period. And the guide says he has no idea how many two- and three-pound smallies fell for this bait. The Virginian rigs this straight-tail worm with a splitshot and tosses it to deep water runs in the mid-river area. Then he merely lets the worm drift along with the current in a very natural manner.

Like lake largemouth fishermen and like Loupe, I rely a great deal on soft plastic baits for jumbo bass. Two of my go-to lures are Mister Twister or Zoom six-inch curl tail worms and four-inch craw worms, rigged Texas-style. A crucial part of fishing these baits is to use at least 3⁄8-ounce bullet sinkers with them. On several trips, the heavier weight has made a difference.

For example, I recently took float trips on Virginia’s James River and West Virginia’s South Branch of the Potomac. On both excursions, my best fish were fat three-pounders that fell to a heavily weighted plastic worm. The jumbo James fish was holding in ten feet of water between two large boulders where the current rumbled through. The South Branch bronzeback was lurking at the end of a rocky shoreline in eight feet of water where the main channel swung in close to the bank. If I had been tossing small soft plastic bait with a 1⁄8-ounce weight, I doubt that these larger fish would have been interested in my offering. Indeed, they wouldn’t have seen it at all before the current unceremoniously washed it downstream.

In the early fall period especially, topwater baits are popular with many river smallmouth fishermen. However, once again, one of my most productive baits is an artificial more associated with lake anglers—a buzzbait, which I rank behind only the Pop-R as a fall topwater. I generally bring along four rods in my canoe and during the day I change lures frequently. But on one of my rods, I always have a ¼-ounce Hart Stopper buzzbait tied on. On a glorious trip down the James River, I caught four two-pound smallmouths in five casts on this lure and I have buzzed up smallies over four pounds with it. Some river fishermen maintain a buzzbait imitates a baby wood duck about to take off, others claim it mimics an injured minnow slashing across the surface. Actually, I think the explanation lies in the fact that stream smallmouths do not strike at this bait as much as lunge at it. The analogy I use is that a buzzbait whirling through a river smallmouth’s domain is equivalent to a friend sneaking up and tapping you on the shoulder while you are watching television. Your reaction would probably be to lurch forward, and that is basically what a bass, safely ensconced in its sanctuary, does when a buzzer comes churning right over its head.

The autumn months typically bring outstanding fishing in the New.