13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Northumbria was one of the great kingdoms of Britain in the Dark Ages, enduring longer than the Roman Empire. Yet it has been all but forgotten. This book puts Northumbria back in its rightful place, at the heart of British history. From the impregnable fastness of Bamburgh Castle, the kings of Northumbria ruled a vast area, and held sway as High Kings of Britain. From the tidal island of Lindisfarne, extraordinary saints and learned scholars brought Christianity and civilization to the rest of the country. Now, thanks to the ongoing work of a dedicated team of archaeologists this story is slowly being brought to light. The excavations at Bamburgh Castle have revealed a society of unsuspected sophistication and elegance, capable of creating swords and jewellery unparalleled before or since, and works of art and devotion that still fill the beholder with wonder.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We have many people to thank, living and dead, starting with the estate of J.R.R. Tolkien for permission to quote from the Good Professor’s works in this book. Without his work, we would never have embarked on our respective careers. Everyone at the Bamburgh Research Project has been unfailingly helpful to us; we would like to thank, in particular, Graeme Young, Sarah Groves and Gerry Twomey. Ian Boomer, Clive Waddington and Alex Woolf gave us their time and thoughts in interviews (as did Graeme and Sarah). Jude Leitch of Northumberland Tourism and Sheelagh Caygill of This Is Northumberland have helped us over the years, and with pictures and promotion for this project. David and Margaret Whitbread have supported the Bamburgh Research Project and us, their sons-in-law, through a decade and more. Tom Vivian and Lindsey Smith were all we could have hoped for from our editors at The History Press. We are very grateful and not a little chuffed that Tom Holland read the book.

Moving to the personal, I (Edoardo Albert) want to thank my parents, Victor and Paola, for everything and my brother, Steven, for getting me through some bad times. Proving that I should never be let anywhere near an Oscars’ acceptance speech, my thanks are also due to my sons, Theodore and Matthew (and for the loan of Theo’s laptop to finish the book when my computer was stolen). Last, but never least, Harriet, indexer extraordinaire and extraordinary wife.

I (Paul Gething) would like to thank my grandfather, Ernest Frank Huggett, who taught me to question. I miss you, Old Timer! Thanks also to Jacob Gething, my constant companion throughout my journeys in Northumbria. It has been a blast, Jake! Finally, thanks to Rosie Whitbread, for everything else. I don’t deserve you

CONTENTS

Title

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1

Northumbria: A Brief History

2

Laying Down The Land

3

The First Northumbrians

4

Religion

5

War

6

Society

7

Culture

8

Food

9

Technology

10

Trade and Travel

11

Burial at Bamburgh

12

Decline and Fall

Bibliography

Kings of Northumbria

Plates

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

Remember when you were young, you shone like the sun.

(‘Shine on you Crazy Diamond’, Pink Floyd)

If Northumbria is a lost kingdom, where would you find it? It’s not on the map. Sure, there’s Northumberland, but while that is certainly composed of land north of the Humber, it’s separated from the river by the whole of Yorkshire. It’s a curious name for a county; transplanting the nomenclature to countries, it’s like calling Canada North Mexico. But the distance of the modern county from its name source gives us a clue: once upon a time, Northumbria was bigger. Much bigger. For a couple of hundred years, between the withdrawal of the Roman legions and the arrival of the Vikings, the kingdom of Northumbria was the pre-eminent realm in the land, its dominion stretching from the Humber in the south to Edinburgh in the north. Before Northumbria’s kings, the rulers of the other kingdoms of Britain bent their knee and offered their homage. To put it bluntly: Geordies ruled us all.1

Not only did they rule us, they renewed us. The kingdom of Northumbria was the fount and inspiration for a cultural and political renaissance that first transformed Britain and then the rest of northern Europe. It produced the brightest scholars, the holiest saints, the greatest kings, the fiercest warriors, the most beautiful art and the most innovative technology of its time.

But then it was forgotten. Most people today will have heard of Bede, but apart from labelling him ‘venerable’ – which relegates the monk to a dim past rather than suggesting him worthy of regard – that will be about the limit of their knowledge. Oswald, Wilfrid, Alcuin, Edwin? Names that have fallen out of fashion, rather than four of the key figures in British and (in Alcuin’s case) European history. There are many reasons for the forgetting, but they can be summed up as fate and fortune, or geography and war. Northumbria’s position at the edge of the world, which once served it well, isolated it in the end. But unfortunately its isolation was not sufficient to protect it from the whirlwind that came out of the north: the Vikings. In the desperate struggle against the northmen, the kingdom of Wessex, insulated by geography from raiders who regarded the North Sea as their private pond, took first place, and history accorded its king, Alfred, the deserved title of ‘the Great’. But two centuries before Alfred, Northumbria’s King Oswald was Britain’s first royal saint – and martyr.

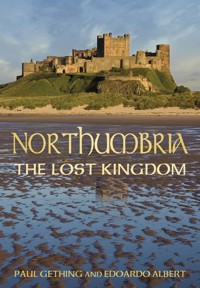

Bamburgh Castle.

In this book, we hope to bring the lost to light, and reveal the splendour of the lost kingdom of Northumbria. To do so, we will use the knowledge gained by archaeologists and historians over the last few decades, knowledge that has produced such a lightening of what were once called the Dark Ages that they’re now called – admittedly with rather less pzazz but considerably more accuracy – the early medieval period.

Of the authors, Paul Gething is an experimental archaeologist, smelter and bladesmith, and one of the directors of the Bamburgh Research Project, an ongoing series of excavations that has been instrumental in our reassessment of the kingdom of Northumbria. He provides the archaeological and historical weft for the other author, writer Edoardo Albert, to weave into a tapestry of the life, times, culture and people of the lost kingdom of Northumbria.

We hope you enjoy the journey.

Notes

1. Paul Gething (born Mexborough) insists that we add ‘and Yorkshiremen’ to the phrase.

1

NORTHUMBRIA: A BRIEF HISTORY

Quam cito transit gloria mundi. (How quickly the glory of the world passes.)

(Thomas à Kempis, The Imitation of Christ)

The Dark Ages2 are full of obscure kingdoms that briefly rose to power, only to sink slowly – or catastrophically – back into oblivion. What makes Northumbria worth writing about rather than Rheged, Lyndsey or Elmet, or any number of petty kingdoms that have been swallowed up over time?

And yet Northumbria is different. Its kings were no less violent; its battles were as often ignoble and rapacious as glorious and decisive; and its peasants have left as little a trace as peasants have elsewhere. The kingdoms of Britain in the early medieval period were no different from their inhabitants’ lives: nasty, brutish and short.

While we grant that Northumbria was a relatively short-lived kingdom, and its wars were certainly nasty, one look at a page of the Lindisfarne Gospels will reveal that it was far from brutish.

On the contrary, perhaps because of the sheer fragility of civilised life, beauty became all the more precious. A monk might spend six weeks working on a single letter, only to have it lost to fire, while a smith might hammer a sword blade 10,000 times and then see it shatter as a result of the quenching process. Beauty was something hard won, and harder still to preserve. But in the brief period of its heyday, in conditions that are as perfect an example of a Hobbesian world as one would not wish to find, Northumbria’s inhabitants made a civilisation that stood shoulder to shoulder and eye to eye with Byzantium (the eastern, enduring arm of the Roman Empire) and the new power of the Carolingian Empire under Charlemagne.

It might be hard to imagine that kings who could not read and whose preferred method of dealing with an inconvenient relative was assassination, might be bulwarks of civilisation, yet they were. For a brief time, little more than a couple of centuries, an extraordinary kingdom flourished, creating islands of culture in the land by the sea.

The kingdoms of Britain and Ireland in the seventh century. There may have been others, too short lived to leave any historical trace. WikimediaCommons

TWO BECOME ONE

Northumbria, as it became called, resulted from the forced union of the neighbouring kingdoms of Bernicia, centred on Bamburgh in Northumberland, and Deira, which had its heartland in Yorkshire, centred on York, which was known at the time as Eoforwic. As Northumbria, the kingdom became the most powerful in the land, with at least two of its rulers powerful enough to be known as Bretwalda, high king of Britain. But tensions between the old Bernicia and Deira ruling families ensured that there were always plausible alternative claimants to the throne. When you add one of the peculiarities of Anglo-Saxon kingship into the mix – if you weren’t constantly bringing new petty kingdoms under your control and scattering the largesse of battles won among your followers, then those followers would slowly drift away to rival courts and kings – and combine this with the lack of an established system of precedence, then you have a recipe for terminal instability. It took an extraordinary personality to hold things together at all and Northumbria had a supply of these for a while. But then, inevitably, factional fighting and the renewed strength of rival kingdoms, Mercia in particular, led to Northumbria’s decline. The decline turned into a fairly rapid fall with the arrival of the Vikings, who annexed the Deiran half of the kingdom in AD 867 and turned the Bernician rump of Northumbria into a dependent earldom.

However, the Northumbrians were still sufficiently sure of their ancient rights to self-determination to prove a major irritation to Harold Godwinson’s attempts to claim the throne for himself after the death of Edward the Confessor in January 1066.

Unfortunately for Northumbrian independence, Harold lost to William, and after a number of failed attempts to pacify the north, the Conqueror decided to destroy its powerbase. The record of the Domesday Book, compiled some sixteen years later, is a grim testimony to how thoroughly his troops despoiled Northumbria. That pretty well marked the end of the kingdom of the north, although the earls of Northumberland continued to play a major part in British history, most notably when Hotspur rebelled against Henry IV in 1403. The fifteenth-century Wars of the Roses were also principally northern affairs, with both the houses – Lancaster and York – once having been part of the kingdom of Northumbria.

DARK BEGINNINGS

Historically speaking, we know next to nothing about what happened in Northumbria after the withdrawal of the legions and the foundation of the kingdom. This is traditionally dated to 547, when Bernicia was founded by a travelling warlord and his band of merry plunderers. Ida, an Anglian adventurer, spotted the potential of a huge isolated craggy rock by the sea – Bamburgh. Generations, stretching back to the Stone Age, had seen its defensive possibilities. The basalt rock, and the succession of strongholds upon it, command the coastal plain. In those days the sea washed right up to the base of the rock, ensuring easy communications up and down the coast and making a siege all but impossible to maintain.

Ida and his men took the stronghold that was already in place, presumably killing or driving out the previous British king of the area.3 What happened then? The most honest thing would be to say ‘we don’t know’, and move on to other matters. But hey, this is a book on archaeology: we’re not going to let a lack of historical sources stop us speculating about what did and didn’t happen!

Exactly how many men Ida had with him is impossible to say, but it was enough. Enough to hold and consolidate his new kingdom, to fight off the attempts by the native British to take back their land4 and enough to be able to pass it on to his heirs. Ida’s achievement is all the more impressive given that the British were well organised, had several strongholds, including Edinburgh, and were capable of fielding armies, if the sources are to be believed. Strathclyde was still a large kingdom in its own right. The Angles, on the other hand, would have had to cross the sea to call on reinforcements. In any case, the early kings would have had only family allegiances to draw on, since fealty was normally only given once a king had proved that he was actually worthy of being a king. So Ida and his sons and followers probably carved out their realm with limited resources and little or no back up.

It is not until Æthelfrith, some fifty years and, according to the king list, seven rulers after Ida – which gives a good idea of the short tenure of a king at that time – that we reach firmer historical ground.

It was Æthelfrith who conquered the neighbouring Anglian kingdom of Deira and brought Northumbria into being, turning it into a real player in the power struggles of sixth- and seventh-century Britain.

But what of the other half of Northumbria? What of Deira? Unfortunately, if the origins of the northern half of Northumbria are dark, those of its southern end, Deira, enter the realm of mystery. One of the few sources we have is the History of the Britons, ascribed to Nennius,5 a Welsh monk, and probably written in the ninth century. The problem here of course is that this is so much later than the events we are interested in. To give a rough comparison, it would be like relying on a contemporary book for news of what happened during the French Revolution.

Of course, our most important written source is Bede, the author of the Ecclesiastical History of the English People, and one of the most remarkable men of Northumbria’s flowering. He wrote the Ecclesiastical History in AD 731, which puts him somewhat closer to events, and undoubtedly his accounts of the later history of the kingdom are the best evidence we have.

Gildas, writing from the perspective of the Britons who were being slowly pushed out of the east and into the west of the country, is our earliest source, probably writing his Ruin of the Britons in the sixth century. According to him, the Anglo-Saxon invaders first arrived as paid mercenaries, hired to fight by British kings who no longer had the services of the professional armies of Rome to call upon. But the mercenaries stayed and gradually started carving out kingdoms for themselves in what became England as the original Britons were pushed west and became the Welsh. But almost everything Gildas says must be taken with a pinch of salt as his account is loaded with his own agenda.

When Augustine, the missionary sent by Pope Gregory the Great to convert the English, reached Canterbury in 597 there was an English king ruling in Deira. The genealogy of the kings in the History of the Britons gives a list of predecessors to the kings of Deira and Bernicia, and both lists terminate with the god Woden. But even assuming the king list is accurate, it still gives us no more than a bald list of names begatting other names for the crucial foundational years of these kingdoms.

So what really happened?

This is the question that has exercised generations of historians and archaeologists. It is in this interregnum between the fall of Rome and the pagan English converting to Christianity that the legends of Arthur originate. But of course, the once and future king was warchief of the Britons in their struggle against the invading Anglo-Saxons – the leader of the (soon to be) Welsh against the English! Ultimately, the Britons lost and the English won, pushing the Celtic peoples into the extremities of the island – Cornwall, Wales and Scotland. But what remains an open question is how much this national transformation was brought about by mass migration and how much by a change in the ruling elite.

HISTORY RESTARTS

From our vantage point, nearly a millennium and a half after the events we’re going on to describe, one major problem remains the predilection the Northumbrian ruling families had for beginning their sons’ names with a vowel, in particular O and Æ. It can be difficult to separate Oswald from Oswiu from Oswine, or Æthelfrith from Æthelwod and Ælfwine in one’s mind. It’s hard not to think that these were dynasties in desperate need of an injection of consonants.

There is a complete list of the kings of Northumbria here, with their dates of reign (as far as these can be attested). But the story of the kingdom is not the same as the story of the kings; some of them can simply remain as names on the list, with nothing more said. But after Ida, the first king we must speak of is Æthelfrith, traditionally the eighth king of Bernicia and the first to rule Deira as well.

Æthelfrith became king of Bernicia around 593. From about 604 he was also king of Deira, thus uniting under him the constituent kingdoms of Northumbria. It is with him that history restarts; an ironic destiny for an illiterate warrior who was one of the key figures in driving the still literate and Christian Britons out of what became England.

In the desperate Darwinian struggles of the sixth century, Æthelfrith proved a master. Bede records him inflicting a devastating defeat on the Scots in 603, ensuring, according to Bede, that no king of the Scots attempted to attack English land again up until Bede’s own day, some 130 years later. With Deira annexed the following year – we don’t know how it was done, whether by force, persuasion, intimidation or some combination of the three – Æthelfrith turned his attention on the Welsh, winning a crushing victory over them around 615.

At the time, the victory must also have seemed a triumph of the old pagan gods over the new Christian God, for as a prelude to the actual battle, Bede tells us that Æthelfrith ordered his warriors to attack and slaughter the Welsh monks who had come to pray for their side’s victory.

This victory established Northumbria as the most powerful kingdom in the land. It would be tempting to think of it as the most extensive too, but that would be carrying modern categories into the past. Nowadays, we tend to think of wars as battles over territories, with armies struggling to take and hold land and cities. The Romans too must have seen things quite similarly, with Hadrian’s Wall marking the limits of empire. But in the semi-anarchy of the sixth and seventh centuries, a more apt image would be of a tooled-up gang venturing into its rival’s territory, aiming to catch those rivals napping and dispose of them before hightailing it back home with all the booty they could carry. There were virtually no towns, castles or centres of population. A king travelled, his retinue accompanied him, and allegiance was marked by giving gifts and pledging aid rather than parcelling things out on maps that didn’t exist. The only form of quasi-taxation came in the responsibility of local landowners to provide accommodation and supplies for the army of the king.

What is clear, even from our distance in time, is that Æthelfrith and his gang were hugely capable warriors who kept their eyes open for the main chance. After all, the Welsh nicknamed Æthelfrith Flesaur, which translates as ‘the Twister’ or ‘the Artful Dodger’. Such a man was not likely to be overly troubled by questions of probity, honour or chivalry. This pretty much epitomised the pagan Anglo-Saxon ideal of a warrior chief: a man who won battles by fair means or foul, disposed of rivals with threats, poison or treachery, and doled out the winnings to his followers. In many ways, the comparison with a modern-day mob boss is closer than a comparison with our modern ideas of kingship, influenced as they are by 1,000 years of Christian and philosophical refining.6

According to Bede, Æthelfrith:

ravaged the Britons more cruelly than all other English leaders, so that he might well be compared to Saul the King of Israel, except of course that he was ignorant of true religion. He overran a greater area than any other king or ealdorman, exterminating or enslaving the inhabitants, making their lands either tributary to the English or ready for English settlement.

(Bede, Ecclesiastical History, p. 97)

Although Æthelfrith had taken control of Deira, at least some of its ruling family had escaped into exile, notably Edwin, the son of the previous king of Deira, and Hereric, Edwin’s nephew. Hereric was disposed of by poison while in exile, with some writers discerning Æthelfrith’s fingerprints all over his murder.7 Edwin proved harder to dispose of.

Once in exile, Edwin seems to have led a wandering life. He must surely have stayed in the kingdom of Mercia, or else it would be all but impossible to explain how he came to have children with a Mercian princess called Cwenburg. The Welsh remembered him too, but not fondly, calling Edwin one ‘of the three chief pests of Anglesey nurtured by itself’.8 There was a tradition that Edwin was raised as foster brother to Cadwallon, later to be king of Gwynedd. If true, there must have been a truly spectacular falling out between them, as when Edwin became king of Northumbria he attacked Gwynedd and conquered Anglesey, driving Cadwallon into exile, only for the Welsh king to gain revenge in blood and battle some years later. But more of that anon. First, we must set Edwin upon his throne: no easy task, as Æthelfrith, having disposed of one Deiran exile in order to secure his throne, had turned his attention to Edwin.

At the time, Edwin was staying with Raedwald, the king of East Anglia, and thus chief of another branch of the Angles. According to Bede, Æthelfrith attempted to bribe, threaten and cajole Raedwald into disposing of his guest and thus removing the last credible claimant to the throne of Northumbria. Raedwald was minded to agree, but his wife persuaded him that to do so would be wrong. Instead, Raedwald, with Edwin, rode out against Æthelfrith, and taking him by surprise, defeated his army and killed the first king of the combined kingdoms of Northumbria. Æthelfrith’s sons survived however, and went into exile. We shall hear more of them later.

By right of battle, and the sufferance of Raedwald, Edwin was now king of Northumbria. But while Raedwald was alive, the East Angle held overlordship over Edwin and indeed, much of Britain; Bede records Raedwald as the fourth Bretwalda, or high king of Britain. While he was prominent in life, he became even more so in death. It is widely accepted now that Raedwald was the king buried in the Sutton Hoo ship.

But once Raedwald died, Edwin ruled supreme. And he set about making himself more supreme.

BRITAIN DIVIDED

To understand the situation in Britain at the time, we need to abandon completely any idea of a country. The land was divided into petty princedoms, many no bigger than a county, and these were ruled by so-called kings. Loyalty was the fundamental binding agent of this society, but it was a personal loyalty, owed to a particular person who happened to be king of, say, Northumbria, rather than there being any obligation to Northumbria itself. You served the king, and were bound to him through personal honour, bought through the ancient rite of gift giving. You did not serve your country, for such a thing barely existed – you served a king.

To give an idea of how small the princedoms could be, Bede tells us that a West-Saxon king sent an assassin to kill Edwin. One of Edwin’s retainers, exhibiting the loyalty that existed between king and man, put his unarmed body between the king and the assassin’s knife, and took the strike himself. In revenge, Edwin set off for distant Wessex and killed no less than five West-Saxon kings. We don’t even know if those five kings exhausted Wessex’s king list – there may have been more! Such was the bond between king and retainer: each was sworn to protect and avenge the other.

Given the tiny size of so many kingdoms, and the small numbers involved in so many ‘armies’, it must have been relatively straightforward for Edwin, with the resources of two large kingdoms at his disposal, to assemble a war band that would overcome most of his opponents. Which is exactly what he did. To Deira and Bernicia, he added Elmet, a British kingdom that roughly occupied the West Riding of Yorkshire (think of the region around modern-day Leeds). Most travel in Anglo-Saxon Britain was done by sea, so Edwin put his ships to good use and invaded and conquered the Mevanian Islands, believed to be Anglesey and the Isle of Man.

If that makes Edwin seem nothing but a bloodthirsty warlord, we must remember that it was this king that Bede said brought such peace to the land that a woman could cross the country from sea to sea with a newborn baby in her arms and not be harmed, and who caused bronze drinking cups to be hung by wells at the side of the road so that travellers might be able to drink. And ‘no one dared to lay hands on them except for their proper purpose because they feared the king greatly nor did they wish to, because they loved him.’9 Machiavelli would have approved in part. This was a king that men feared, one that could parade with a standard bearer like the emperors of old and not seem like a popinjay but a ruler of genuinely imperial stature, even if his lordship was over a straightened land in straightened times.

And Edwin eventually became the first Christian king of Northumbria.

The king was baptised on Easter day AD 627. There’s much more about this key event in our chapter about religion.

In the end, this Christian king of the English Northumbrians was killed in battle by the Christian king of the Britons, who had allied with the pagan king of Mercia. In an age of small realms and shifting alliances, some strange leagues could form, and none was more unusual than that between Cadwallon of Gwynedd and Penda of Mercia.

Having been defeated and driven into exile by Edwin, Cadwallon had regrouped and, with Penda of Mercia,10 attacked Edwin. In October 633 Cadwallon and Penda met and defeated Edwin, killing the king. His two older sons by his first wife were with him at the Battle of Hatfield Chase: one died there, the other was taken prisoner by Penda and killed later.

The victorious Cadwallon drove on to Northumbria and, according to Bede, laid the kingdom waste, conducting what was almost a war of ethnic cleansing against the inhabitants. While it’s unlikely that Cadwallon really aimed to exterminate every Anglo-Saxon in the country – after all, he was allied with the thoroughly Saxon Mercians – he does seem to have reserved an unusual fury for the defeated Northumbrians. Wars were generally a matter of kings and their war bands; the outcome for the peasants usually meant little more than a change in the man they paid their duties to. But Cadwallon seems to have extended his campaign to the non-fighting sections of the population in Northumbria.

THE RETURN OF THE KING

For a time it may have appeared that the British might succeed in regaining their lost dominion in the north. But when Edwin slew Æthelfrith and took the Northumbrian throne for himself, Æthelfrith’s wife and surviving children had taken the normal course of action of a defeated ruling family: flight into exile. But though their actions were expected, the destination they chose was less so – the island of Iona.

This island off the west coast of Scotland had become the key centre of Christianity in the region. Given that Bede tells us that Æthelfrith had killed some 1,200 Christian monks before his successful battle against the Welsh, the decision of his still pagan family to seek refuge among those monks’ co-religionists seems noteworthy. We know nothing more of why they made this decision, but the welcome they received suggests that it was the right one.

The four children of Æthelfrith stayed on Iona for some years, growing to adulthood there. It must have been on Iona that Oswald, later to be king of Northumbria and saint and martyr of the Universal Church, received instruction and entered into the faith that his father had fought against: Christianity. And it was from Iona that Oswald returned to the mainland with a small army to attempt to wrest his father’s kingdom from Cadwallon.

Before the armies met, at a place called Heavenfield near Hexham in modern-day Northumberland, within sight of Hadrian’s Wall, Oswald had a cross erected and knelt, holding it in position as its setting in the earth was filled. This was a time when men expected their gods, or their God, to deliver in this world as much as the next: victory under the sign of the cross would lead to Oswald and his men taking up the cross across Northumbria. Defeat meant death unshriven. It was time for God to put up or push off. He put up.

The present-day Iona Abbey, Scotland. WikimediaCommons

Despite inferior forces, Oswald won, and Cadwallon was killed. Oswald, in the year of Our Lord 634, became king of Northumbria. Cadwallon’s Britons were decisively defeated. Never again would the Britons come close to re-establishing control over their former territory. In fact, the Britons were now well on their way to becoming the Welsh.

God having delivered for Oswald, the new king did the same for God. He invited a mission from Iona to come to Northumbria. Aidan11 arrived in Northumbria in 635 and established a monastery on Lindisfarne, the soon-to-be Holy Island, within sight of the royal stronghold at Bamburgh.

From there, Aidan and his monks set out to evangelise Northumbria, with the king acting as patron, sponsor and, initially at least, translator. When Aidan first arrived he could not speak the language of the locals, whereas Oswald, having lived on Iona, was fluent in both British and English.

Not only was Oswald king of Northumbria, but he seems to have exercised dominion over the other kingdoms of Britain. His reign lasted eight years, and firmly established Christianity in Northumbria in a way that Edwin’s conversion had not.

But it was Edwin’s old enemy, Penda of Mercia, who brought him down. In 642 Penda defeated Oswald at the Battle of Maserfield. The victorious pagan cut up Oswald’s body and stuck his head and arms on poles.

If God rewarded his adherents and punished those who fought against him, this seemed to be a devastating setback for Christianity. The stubbornest pagan in the land had defeated a man whom Bede writes of as being a saint in his life as well as his death. The situation surely could only get worse for the new faith, for Penda was now the most powerful king in the land, installing and removing monarchs at whim. Possibly to ensure the permanent weakening of Northumbria, Penda split the kingdom into its two constituent realms. Oswald’s younger brother, Oswiu, ruled Bernicia, but he did so at Penda’s pleasure.

Politics is personal, and possibly no more personal than at this time, when people looked to their immediate families and kin for support, aid and refuge. You might kill one king, but a glance at the royal genealogies of the time shows that a nemesis often took the form of a relative of the slain monarch. Penda was no exception. His death eventually came at the hands of Oswald’s younger brother, Oswiu.

Oswald. © 2012 Walters Art Museum

However, Penda’s blood stayed in his veins for many years after Oswald’s death. Oswiu was king at the sufferance of his brother’s killer, but, displaying a sound grasp of the practicalities of the power politics of the time, he apparently bought off the Mercian ruler by paying him huge amounts in tribute.

Quite why Penda eventually decided to take the money in a more direct manner – that is, over dead bodies – is not certain, but in 655 he invaded. As so often, the exact details, or indeed locations, of what happened next are not entirely clear, but the outcome was as stark as it usually was in sixth-century politics: Penda died, Oswiu won.

The death of Penda, who had remained stubbornly, perhaps even magnificently, pagan throughout a time of extraordinary religious change marked the effective end of paganism as a political and religious force in the land. While it no doubt took many, many years before the general population could be effectively evangelised, from now on all the country’s rulers, whether they were English, British, Scottish, Pictish or Irish, were Christian. Even Penda’s own sons, who went on to rule Mercia, were Christian.

As for Oswiu, he was now the dominant king in the land. And though his domination did not last that long – the Mercians revolted against the client king he’d established and put one of Penda’s sons back on their throne – he did achieve something unique among Northumbrian kings up to that time: he died, in his bed, after falling ill. It was 15 February 670 and he was the first Northumbrian king not to die in battle.

His son, Ecgfrith, was not so fortunate. He ruled over a Northumbria at the height of its power, but died during a disastrous sortie against the Picts of Scotland in 685. Bede states that Northumbria’s political decline began with his death, although historians argue that power had already started to shift south to Mercia during his reign.

In any case, the most important aspects of Northumbrian history shifted from the political and military to the cultural and religious.

Viking ship detail. WikimediaCommons

Think on this. In 635, when Aidan arrived in Northumbria, he found a pagan and illiterate people. Within a century, Northumbria had become the key intellectual, religious and scholarly centre of northern Europe. Its priests and monks, men and women such as Bede and Hilda, Wilfrid and Alcuin, studied the Scriptures and works of classical learning, produced exquisite volumes of the Gospels, sent missionaries and representatives to the pagans of Germany and the court of Charlemagne, and assembled the finest libraries to be found in northern Europe. Men who, in the words of Pope Gregory, had worshipped sticks and stones but a generation ago, spoke in Latin, read Greek, wrote treatises on the tides and established that the world was, against the apparent evidence of the senses, round.

A model of the Viking ship burial excavated at Gokstad in Norway. The original would have been more frightening.WikimediaCommons

It was, in its own way, a golden age. Indeed, so thoroughly had the new religion penetrated at least the upper echelons of society that Ecgfrith’s successor, Aldfrith, was seen as a scholar as well as a king. In fact, Bede records only one battle as taking place during his reign, which suggests a period of quite unparalleled peacefulness.

Thereafter, a number of unremarkable kings ruled, generally for short periods of time, trialling the chronic instability that would eventually so weaken the kingdom. What is notable is that two of them, rather than following the time-honoured tradition of violent death, voluntarily gave up their crowns and entered monasteries: Ceolwulf (reigned 729–737) and Eadberht (ruled 737/8–758). But afterwards, the history of the kings of Northumbria becomes a sad, bitter and, for our purposes at least, slightly pointless tale of usurpation and murder, with names passing in a blur of dates.

And then the Vikings came.

Yes, we know all the historical revisionism, we know the Vikings were great traders and travellers, we understand that history is usually written by the victors, but if the victors are illiterate then the losers get an unexpected chance to paint their enemies in all the gory colours of their defeat; we know all this, and some of it is even true.

But for the kingdom of Northumbria, history ends when the long ships appear. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records:

In this year [793] fierce, foreboding omens came over the land of Northumbria. There were excessive whirlwinds, lightning storms, and fiery dragons were seen flying in the sky. These signs were followed by great famine, and on January 8th the ravaging of heathen men destroyed God’s church at Lindisfarne.

Interview with Graeme Young

1. Who are you and what is your area of expertise?

My name is Graeme Young and I am a 46-year-old professional field archaeologist. Over my career I have excavated a considerable variety of sites dating from the Mesolithic to the industrial era, but my particular area of expertise is in the medieval period, both early and later. I am also one of the four directors of the Bamburgh Research Project.

2. Describe your specialism simply.

The meticulous excavation and recording of complex and deeply stratified archaeological sites would about sum up what I do best.

3. How have archaeological investigations, such as those at Bamburgh, changed our views of Northumbria?

The story of Northumbria at one time was very much based on the historical evidence of texts such as Bede’s Ecclesiastical History. Archaeology over the last few decades has transformed our understanding and brought these texts to life, particularly with the excavation of sites like Wearmouth and Jarrow illuminating the pages of Bede by revealing a monastic culture every bit as sophisticated as that he described. With secular sites such as Bamburgh (high status) and Shotton (low status) we have very little descriptive evidence, as monks tended to write more about monasteries, so the archaeology takes on an additional significance as it is often the only way we can get close to the architecture and cultural life of the period.

4. What do you consider the most important change in our views of Northumbria?

I would say that archaeology has painted a more sophisticated cultural picture of Northumbria over recent years than we had deduced from texts. I would also add that cemetery sites have put us closely in touch with the often painful and brutal lives of medieval Northumbrians. Bamburgh in particular is providing evidence that stone architecture was in use in a secular context from a much earlier period than had previously been thought. I would add my voice to those who see archaeology countering the historical label of the early medieval period as the ‘Dark Ages’.

5. Who do you consider to be the most important figures in Northumbrian history?

There are obvious answers such as King Oswald, who played such a key role in the Christianisation of the kingdom, bringing it into the European medieval cultural and intellectual mainstream. Given the importance of Northumbria at the time, this has significance for the wider development of England. There is also Bede, who has such a key role in the development of an English intellectual culture and the recording of history. Perhaps even the creation of an idea of England itself. In fact he is really of such significance that he should be seen as a European figure.

I would add the almost unknown figure of Oswulf, one of the tenth-century Bamburgh earls. He was in no small part involved in ending Eric Bloodaxe’s reign as king of York, which led to the final creation of a kingdom of all England. It’s quite an important role to have played and should be better remembered.

6. Which areas of Northumbrian history are most likely to change in future with further investigation?

I think there is a great deal that archaeology has to add with regard to reconstructing the past economy. At the moment, we have a rather limited data set with which to map the scale and productivity of early medieval farming, which would have so much to tell us about the lives of early medieval Northumbrians. I think further palaeoenvironmental work, from Bamburgh not least, will add hugely to our understanding of the Northumbrian economy.

7. Why was Northumbria important?

Northumbria played a major role in the introduction of Christianity to England and perhaps the key role in the decision to turn to Roman rather than the Irish Christian tradition for its lead. This led to an alteration in the outlook of England, moving from a more Scandinavian one to a Franco-Italian one. The implications of this are still unfolding today in terms of our relationship with our continental neighbours.

8. Why is Northumbria important?

I think all history starts as local and regional history, so for those of us from Northumbria, its history still has an impact on how we see ourselves. The history of the region has real relevance today, particularly with the rise of the Scottish independence movement. Why, if not due to Northumbria’s history, is the border where it is and England and Scotland the places they are? We are still in so many ways the border region that links London and the south to what lies beyond the immediate English orbit.

9. Is there anything else you would like to add?

At a time of such tumult and with economies and so many peoples’ lives in jeopardy, archaeology and history can seem a little frivolous. I would argue though that it is at such times of crisis, or potential crisis, that knowing how we got here and what failures and successes past generations have had can help us find our way. Or at the very least give us some comfort that all troubles pass in time.

What is Archaeology?

Archaeology is a science. Many people see archaeology as an art rather than a science, but in fact archaeology is one of the broadest of sciences, its range of constituent disciplines ranging from the hardest of hard sciences – isotopic analysis, say, or neutron activation analysis – to the social sciences such as sociology and psychology. The findings of archaeologists can also illuminate and be illuminated by disciplines such as art history and history itself, which aren’t sciences but do have rigorous intellectual foundations. In fact, we’re hard put to think of a science that uses a wider range of intellectual and technical tools to interrogate its subject. But then, that is to be expected, since the subject of archaeology is humanity and its interaction with our world and its physical, animal and plant constituents. It’s a big subject; quantum mechanics is easy peasy by comparison.

Notes

2. Yes, we know ‘Dark Ages’ is no longer the preferred epithet, and it’s true, it is the wrong label in almost all ways, carrying unjustified implications of congenital stupidity and evil. But in one respect at least it really was dark – we still can’t see it clearly. Early medieval is the new name for the period sandwiched between the end of the Western Roman Empire and the Norman Conquest.

3. Bede, in his history, refers to the ‘capture’ of Bamburgh, so it seems likely that there was a stronghold there already. Archaeologically, there is a suggestion of a wooden palisade set into a wide clay bank from the right period, which was quickly replaced with a stone wall. Carbon 14 dates have not yet been done on the remains, so the link between the identification of the remains found and Bede’s account remains tentative, but it does tie in perfectly with his description.

4. The poem Y Gododdin suggests that the British made at least one concerted effort to reconquer their territory from the Angles. The dating of Y Gododdin is difficult but it seems likely to be from close to the time of Ida. Gildas also mentions the British waging war on the Saxons (Angles) and Nennius (in the ninth century) describes Urien of Rheged and the Kings of Strathclyde waging war on the ‘sons of Ida’. (Source: Rollason, D., Northumbria 500–1100, p. 103)

5. Naturally, this authorship is contested, with David Dumville arguing that the History is the work of an anonymous writer based at the court of Gwynedd in 820–830.

6. Although Æthelfrith might have been more John Gotti than John of Gaunt, it’s pretty certain that his use of language would have been better, if not necessarily cleaner, than modern gangsters. Listening to transcripts of wiretaps on Mafia bosses is to make one despair of the future of language beyond a limit of four letters to a word.

7. Ziegler, M., ‘The Politics of Exile in Early Northumbria’ in The Heroic Age, 2, autumn/winter 1999; Kirby, D.P., The Earliest English Kings.

8. Blair, P.H., Northumbria in the Days of Bede, p. 42.

9. Ibid., p. 43

10. It’s not clear whether Penda was yet king of Mercia at the time of this alliance, but the victory over Edwin would certainly have helped to increase and consolidate his power.

11. Aidan was actually the second representative sent from Iona; the first missionary failed in his mission to convert the Northumbrians, claiming they were too stubborn.

2

LAYING DOWN THE LAND

The green earth, say you? That is a mighty matter of legend, though you tread it under the light of day!

(J.R.R. Tolkien, The Two Towers)

Standing on the rock at Bamburgh, walking the Cheviot Hills, marking the old Roman bounds along Hadrian’s Wall or pitching out to the Farne Islands on a boat, the visitor to Northumberland is brought face to face with a land where geography dominates. Humanity has always been thin on the ground here, and our presence still feels tenuous. In this chapter, we will look at the long history of Northumbria and try to understand how the forces that formed the land gave birth to, nurtural and constrained the civilisations and peoples that have lived there over the centuries.

CATASTROPHE AND CONTINUITY

Dropping into the personal for a moment, both authors remember the quite literally jaw-dropping impact of first seeing Northumberland’s unique combination of landscape, history and architecture brought into stark focus by Bamburgh Castle, squatting on the horizon and dominating land, sea and sky. But how did the landscape assume its current form? To answer that, we have to go back a long, long way.