Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The story of the Bamburgh Sword – one of the finest swords ever forged. In 2000, archaeologist Paul Gething rediscovered a sword. An unprepossessing length of rusty metal, it had been left in a suitcase for thirty years. But Paul had a suspicion that the sword had more to tell than appeared, so he sent it for specialist tests. When the results came back, he realised that what he had in his possession was possibly the finest, and certainly the most complex, sword ever made, which had been forged in seventh-century Northumberland by an anonymous swordsmith. This is the story of the Bamburgh Sword – of how and why it was made, who made it and what it meant to the warriors and kings who wielded it over three centuries. It is also the remarkable story of the archaeologists and swordsmiths who found, studied and attempted to recreate the weapon using only the materials and technologies available to the original smith.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 498

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To Robert Dudley

First published in 2022 byBirlinn LimitedWest Newington House10 Newington RoadEdinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Paul Gething and Edoardo Albert, 2022

ISBN 978 1 78885 523 5

The right of Paul Gething and Edoardo Albert to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

Helen Stirling Maps 2022. Contains Ordnance Survey Data.© Crown Copyright and Database Right 2022.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record of this book is available on request from the British Library

Papers used by Birlinn are from well-managed forests and other responsible sources.

Designed and typeset by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Contents

Maps

Introduction: Finding the Bamburgh Sword

Part One – The Evolution of Swords

1 What Is a Sword?

2 The Prehistory of Swords

3 The Age of Iron

4 Medieval Swords

Part Two – Creating the Bamburgh Sword

5 Getting Iron

6 The Smith

7 Forging the Sword

8 The Hilt

9 The Scabbard

10 Gold and Garnets

Part Three – The Sword in Action:Life and Death in the Seventh Century

11 The Buried Sword and the Drowned Sword

12 White Pebbles

13Hwaet! The Warrior in Tale and Culture

14 War, What Is It Good for?

15 Swordfighting for Beginners

16 There Will Be Blood

Epilogue: The Perfect Sword

Acknowledgements

Index

Northern Britain and Ireland, c. ad 650.

Bamburgh Castle, c. ad 650.

Introduction

Finding the Bamburgh Sword

Archaeology comes out of the ground. Tutankhamun was interred in a pyramid in Egypt. Knossos was found under a hill on Crete. The Staffordshire Hoard was dug from a field in the county that named it.

Not the Perfect Sword. This sword – the sword that, of all the thousands of blades ever forged, comes closest to being perfect – this sword came out of a suitcase.

Admittedly, when the ‘perfect’ sword was taken from the suitcase it was a long way from being perfect: it was broken. It had no hilt either, just the tang (the extension of the blade that fits into the hilt) and the top half of the sword.

In the normal course of events, archaeological finds come out of the ground because context is key. The foundation upon which archaeology lies is that older is deeper. This draws on the much older geological concept of superposition, which was first postulated in 1669 by Nicolas Steno and later popularised by William ‘Strata’ Smith: if something is beneath, it must be earlier.

There are exceptions to this. Someone digging or laying foundations might cut through other, older layers, introducing a newer element deeper underground. But the principle is clear: underneath is older. In the context of archaeology as science, this is crucial. For one of the core elements of the scientific method is that experiments must be replicable and repeatable. But you can’t do that with archaeology. A dig, dug, is done; you can’t put all the finds back and have another go. Each excavation is unique and singular. On the face of it, this prevents archaeology being a true science since no dig is repeatable. Yes, archaeology might employ all sorts of cutting-edge scientific techniques – isotopic analysis, statistical modelling, dendrochronology, carbon dating – but at its heart are non-repeatable, non-replicable excavations. By strict Popperian criteria, archaeology is not a science.

Archaeology becomes a science by recording. Modern archaeology, as a scientific discipline, rests upon making a complete record of the excavation and a painstakingly accurate description of the context of each find. That is, each find is recorded in place, geographically, and in time, vertically, its history determined by where it lies in the time sequence uncovered as the archaeologists slowly remove each layer of the past. Thus, while no dig can be repeated, the evidence and chain of inferences that leads to each find being dated and placed into history can be checked by any other archaeologist going through the excavation reports. Findings can be assessed and, if necessary, corrected. In the modern era many sites have been reinvestigated, and there is even a small subset of sites where the spoil heaps of previous excavations have been themselves excavated to recover evidence missed initially, from Stonehenge through to Hadrian’s Wall.

With this being the case, it would seem that a sword in a suitcase could be nothing more than a curiosity. On its own, it tells us no more than the brute fact of its existence, unmoored to any place or time.

The story of how the sword came to be in the suitcase is a saga in itself. We now know that it was excavated from Bamburgh Castle, Northumberland, in 1970. The archaeologist who found it was named Brian Hope-Taylor and when he found the sword he was at the peak of his professional and public life. Hope-Taylor, with his sweep of blond hair and penchant for driving around the countryside in sports cars, was a major figure among the first generation of professional archaeologists. He had served in the Second World War in the RAF before beginning to dig in the 1950s. Hope-Taylor had also trained as an artist – some of his paintings are held at Wolfson College, Cambridge – but like so many of his contemporaries he learned the skills of excavation by digging. It was his excavation of Ad Gefrin during the 1950s, the site of a palace of the Northumbrian kings, that made his name. The site itself is a field beneath a hill called Yeavering Bell, which has the tumbledown remains of an Iron Age hillfort girdling its summit. The hillfort is visible; the remains of Ad Gefrin, which were all constructed from wood, are not.

Yet from his delicate excavations, Hope-Taylor extracted the layout of a number of extraordinary structures that he tied into the history of the kingdom of Northumbria. For Bede tells us that in ad 627, the Italian missionary Paulinus went with King Edwin of Northumbria and his wife, Æthelburh, to Ad Gefrin and there preached the new religion to the Northumbrians, baptising many hundreds in the nearby River Glen. At Ad Gefrin, Hope-Taylor found the remains of timber buildings, including a great hall that was 26 metres (85 feet) long, kitchens, weaving shed, a huge corral to hold cattle or horses brought in tribute to the king from the surrounding hills, and a grandstand with banks of elevated seating. Hope-Taylor placed Paulinus, preaching the new religion, at the focus of this grandstand.

Archaeology provides sections through time in a particular place. History tells the story of what happened. At Ad Gefrin, Hope-Taylor brought the historical story and the archaeological snapshot together. His report of the excavation, Yeavering: An Anglo-British Centre of Early Northumbria, became an archaeological classic, marrying precise excavation with an imaginative entry into the past, illustrated by Hope-Taylor’s exquisite drawings. However, the fact that the dig report was only published in 1977, more than 20 years after excavations had finished, highlights an ongoing problem in archaeology: many archaeologists find it very difficult to complete the final report on an excavation with which they have become identified. Indeed, Yeavering would prove to be Hope-Taylor’s first and last complete excavation report. Despite the many years work he also did at Old Windsor in Berkshire and Doon Hill in Scotland, he never finished another report.

However, Hope-Taylor had made most of his findings about Ad Gefrin public long before publication, having presented a report on the excavation to the Society of Antiquaries and written his PhD on the dig. Indeed, his work was so highly rated that Hope-Taylor was made a lecturer in archaeology at Cambridge University on the back of his excavations at Ad Gefrin despite never having done an undergraduate degree himself.

Among the many sites that Hope-Taylor never wrote up was Bamburgh Castle. He excavated there in two phases, from the late 1960s to the early 1970s. He had left his excavation incomplete but clearly expected to return and finish digging for when the site was re-excavated in the early 2000s, the archaeologists found the section grids and marker tags still there, under the ground. Hope-Taylor had simply covered them over with tarpaulins and plastic sacking and backfilled the site: standard practice among archaeologists when leaving a site at the end of the season and expecting to return next year.

But Hope-Taylor never returned to Bamburgh. In the 1960s, he had become the public face of archaeology, presenting two successful TV series which highlighted his gifts as a communicator – he had been a child actor and took to the medium as one born. He was on the verge of becoming a major figure in British public life. Instead, he withdrew, first from public life, then from teaching, finally from his home in Cambridge, going to Wooler in Northumberland. After a bout of ill-health, he subsequently returned to Cambridge but did not resume his archaeological work, instead devoting his last years to the study of old churches in Essex.

When Hope-Taylor died in 2001, one of his old students went to his house to see what there was of archaeological interest in it. Ian Ralston had first dug with Hope-Taylor as a boy in Scotland at the Doon Hill site near Dunbar and he had gone on to become a leading archaeologist in his own right. Ralston had done his best to remain in contact with Hope-Taylor, even during his final decade when Hope-Taylor was consciously withdrawing from human society.

Ralston arrived at Hope-Taylor’s house to find that it had become the depository of a lifetime of archaeology. It was stacked with boxes and files and finds; even the bed was covered, leaving no room for someone to sleep. Hope-Taylor had become a hoarder. But it was a hoard of the greatest archaeological interest. To sort, catalogue and preserve it, Ralston enlisted another of Hope-Taylor’s old students, Diana Murray, who worked for the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS). Arriving just in time to stop house clearers consigning Hope-Taylor’s muddled but invaluable archive to a waiting skip, Murray arranged for the contents of his house, and a leaking garage that held finds Hope-Taylor could not fit into his house, to be taken to Edinburgh for conservation and sorting.

Which was where Paul Gething and the archaeologists of the Bamburgh Research Project (BRP) come into the story.

They had begun digging at Bamburgh Castle in 1997. In 1998, Graeme Young, one of the four founders of the BRP along with Paul, Rosemary Whitbread and Phil Wood, contacted Hope-Taylor to ask what he had found when he had excavated the castle 25 years earlier, and how large an area he had excavated. However, Hope-Taylor proved evasive and unwilling to provide many details on what he had found – and what details he did provide turned out to be inflated. For instance, he claimed to have excavated all of the West Ward of the castle, but the BRP later found that he had only dug 10 per cent of it.

Faced with this stonewalling from Hope-Taylor, the BRP archaeologists advertised in and around Bamburgh, asking if anyone remembered what areas the Hope-Taylor excavations had investigated. Many people came forward. One of the castle’s tour guides had worked on the dig as a boy and showed the BRP where Hope-Taylor had excavated. Another lady brought them a set of photographs of the site that Hope-Taylor had asked her to look after but had never returned to collect. The castle custodian also showed the archaeologists the store-rooms that Hope-Taylor had used during his excavations. These had been closed after he left the site and not reopened.

Unsealing the door, the archaeologists found themselves faced with a nascent archaeological site: Hope-Taylor’s field office, untouched since he had left it, with desk, tools, soil samples and some finds. But the reopened office held none of Hope-Taylor’s site reports, so they could not trace what he had done.

Then, the phone rang. It was someone from the RCAHMS telling them that Hope-Taylor had died, which they knew, and that the committee had taken possession of his archive, which they did not know.

Would they like to come up to Edinburgh to see if there was anything relevant to their excavations at Bamburgh?

Yes, they would like to. Very much. So, not long afterwards, Paul and some of the other archaeologists drove to Edinburgh, where they were taken into a large room containing the many boxes, files, cases, bags and crates that held Brian Hope-Taylor’s life work.

On first seeing the spread of items and the complete lack of legible labelling, it seemed that finding anything relevant to their excavations at Bamburgh would be impossible. But looking through the boxes, Paul spotted a box containing items with the stratigraphy he had been digging at the castle. The stratigraphy of a site is the geographical equivalent of a fingerprint, unique to its specific location. Having found one box with this characteristic stratigraphy, the BRP archaeologists investigated the nearby boxes. They quickly realised that the boxes containing finds and reports with grids labelled ‘S’ and ‘L’ in one plane, and 6 to minus 1 in the other plane, were all associated with Bamburgh.

While the BRP archaeologists were looking through these boxes, one of the RCAHMS staff brought Paul a suitcase and suggested he might find its contents interesting. Inside were four corroded pieces of metal. They had been found loose in the suitcase, so the conservators had wrapped them up in acid-free tissue paper. Picking them up and inspecting them, Paul quickly realised that two of the pieces fitted together, forming a whole broken sword. Another was the head of a broad axe. And the fourth was also a sword, broken in two. He was holding the upper half, including the tang, in his hands. There had been no labels with the finds, but the suitcase had been in among the stuff from Bamburgh, so it was reasonable to assume that Hope-Taylor had excavated them from the castle. Proof of that would depend upon them being able to find details of Hope-Taylor’s finding of the swords and axe head in his site reports. But holding the broken-off sword, Paul was immediately struck by the suspicion that it had been no ordinary weapon.

Swords are individual. Each is unique, with its own set of characteristics, a style that it impresses upon the man wielding it who in turn exerts his own style upon the sword. A sword is not a dumb brute of a weapon but rather one that works in partnership with its wielder. Depending on the sword and the swordsman, the partnership may be one of equals, the sword may be superior to its wielder, or the swordsman may have to impose his own style upon a crude and poorly made weapon.

The swords from the suitcase were not poorly made weapons. Paul was sure of that. But Hope-Taylor apparently had not regarded them as anything special: he had certainly not labelled them as worthy of more attention.

Gut instinct is a vital part of archaeology, but it is seldom mentioned in the literature. It’s not possible to quantify or record, but the deep feeling some archaeologists have that this is the right place to dig or that that artefact requires closer scrutiny has been a major driver of many discoveries. While archaeologists might ascribe these instincts to the gut, it’s more likely due to a combination of years of experience, deep familiarity with the period and the employment of all the senses when assessing a landscape or object. Sometimes, the sound of the soil falling from the trowel can be a vital clue. With swords, it is the feel, the weight: the life.

A truly good sword feels alive in the hand, as if it is an extension of the body.

Despite their sorry state, Paul got that feel from the two swords in the suitcase. But to determine if this sense was accurate, some tests needed to be done on the swords and the axe head.

Dr David Starley, archaeometallurgist at the Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds, was the perfect man to run those tests: not only is he one of the best archaeometallurgists in the world but he has a deep knowledge of ancient swords. What’s more, he was prepared to run a full battery of tests on the finds: scanning electron microscope, photography, X-ray and magnetic resonance.

But all this testing takes time. The swords and the axe head, with the blessing of RCAHMS and the custodians of Bamburgh Castle, were shipped off to the Royal Armouries Museum while the BRP archaeologists tried to make some sense of Hope-Taylor’s Bamburgh site reports.

The problem was that the grid system Hope-Taylor had employed made no sense. ‘S’ and ‘L’ marked either ends of one axis, but no one knew what the ‘S’ and the ‘L’ stood for: they were not standard measures in archaeology, which usually employs the compass points for the basis of the grid system. For weeks they all puzzled over it, referring to Latin dictionaries, trying every sort of combination of compass fit that they could imagine. But none of these made sense.

Then, standing on the castle battlements, looking out to the Farne Islands that sit low in the water two miles out from land, Paul thought that the sea was unusually tranquil that day.

He was looking at the sea from the land.

‘S’ and ‘L’.

That was it. ‘S’ stood for ‘sea’, and ‘L’ for ‘land’. Looking at the site reports afresh, everything fell into place. Most importantly, it meant that the BRP could establish the context in which Hope-Taylor had found the swords and the axe head. Finding the context meant that the swords and the axe head were no longer merely random bits of corroded metal, of some interest because of the way they had been forged but useless for archaeological purposes. Now they were finds that had their proper place in unfolding the story of early medieval Britain.

Reconstructing the record of Hope-Taylor’s Bamburgh excavations was long, detailed, frustrating work. For over three years the archaeologists pieced together Hope-Taylor’s site record from photographs, site notebooks and a very few accounts from people who had actually seen or dug the site as schoolchildren. It soon became obvious that there were huge holes in the archive and much had been lost forever. It took the re-excavation of a Hope-Taylor test trench to identify the location of the cache with accuracy.

But finding the context did mean that the BRP could date when the swords were lost and how. The ‘when’ was the 10th century, and the ‘how’ was what Hope-Taylor described as ‘a catastrophic burning event’. A devastating fire had burned down the building in which the swords were being kept and they were lost in the wreckage. Broken swords, particularly if they were valuable and venerable, would often be reforged. The context of the site where Hope-Taylor found the swords suggested a smithy to Paul. With the fire necessary for forging weapons, and with buildings made predominantly of wood, uncontrolled fires were not uncommon in smithies. The two swords were probably awaiting repair and reforging in the smithy when a fire got out of hand. Amid the debris and ashes, the swords were lost for a thousand years.

However, until Paul got the report back from the Royal Armouries Museum, he could not say whether the swords had been worth reforging. They might simply have been broken swords, scrap metal that the smith was keeping on a shelf, waiting on some free time to forge them into something else.

Archaeology is not quick. The four young archaeologists recognised that the excavations in and around the castle was an enterprise that would take many years to complete and many trowels to dig. With funds always a difficulty in archaeology, they realised that the depth, complexity and stability of the site meant that they could combine training with digging, providing grit-under-the-fingernails experience for archaeology undergraduates and to anyone interested in the deep past with two weeks to spare in the summer. So, the dig became the Bamburgh Research Project, and it’s still going on, digging down into the past and still making new discoveries after more than 20 years in the field – as well as helping to train the next generation of British archaeologists.

* * *

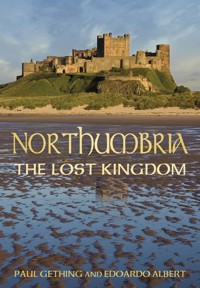

For those who have not seen Bamburgh Castle, the stronghold sits atop an outthrust of the Great Whin Sill, a layer of extra-hard dolerite stone that underlies much of the geology of the north-east of England. This dolerite was laid down 300 million years ago when a layer of liquid magma, rising from the Earth’s core, was diverted before it could reach the surface and become a volcano. Instead, the rising magma found the gap between two layers of sedimentary rock and squeezed into the space. Imagine squeezing a tube of toothpaste into the space between two horizontal boards: it will spread out, forming a thin layer between the two boards, the thickness of the layer determined by how far apart the two boards are. The liquid rock did the same, spreading out and forming a layer that spread across what would become northern England and southern Scotland. In some places, of course, there was no gap between the layers and the slow-moving liquid rock flowed around these places, creating a geological underscape that would have looked like the wetlands of the Scottish Flow Country when seen from above: flat but dotted with many pools and lakes where the magma had not been able to penetrate between the layers.

Dolerite is a very hard rock but the layers of carboniferous rock above and below it are much softer. Millions of years of erosion have gradually worn away the top layer of stone, reaching the dolerite underneath. Those areas that the liquid rock was not able to reach have continued eroding at a relatively faster rate but where the dolerite has been exposed, it has resisted the forces of water and wind longer and harder, creating slabs and extrusions of hard, long-wearing rock in a broad band through the north-east. The local quarrymen knew the rock well and gave it its name, Whin Sill, a name later adopted by the first geologists. The Whin Sill stretches beyond Bamburgh to the Farne Islands a few miles out to sea, with each of the islands characterised by steep cliffs and flat tops.

Bamburgh itself squats beside the sea. Nowadays, there is a magnificent beach between the castle and the sea that, at low tide, stretches a good half mile to the water’s edge. But the beach is recent. It is a product of a storm of apocalyptic proportions in 1817 that dumped a beach worth of sand below the castle, having picked it up from further north and moved it south during the course of a few wild days. When the swords were forged, the sea washed up to the base of the rock at high tide.

The rock itself rises 45 metres (150 feet) above the surrounding land. It has a fairly flat top covering nine acres in an elongated teardrop shape. The original entrance to the castle was what is now called St Oswald’s Gate at the top, north-eastern corner of the rock, the far side from the modern entrance. The entrance was probably placed there because it lies closest to an area of beach that shows evidence of having been a landing site and mooring place for boats in the past, before the great storm of 1817 changed the topography of the area beyond recognition. With Bamburgh being on the coast, and the road network slow and unsafe, most travellers would have reached the castle by boat, so it made sense for the main entrance to be close to the harbour.

Atop the rock, over towards St Oswald’s Gate, the BRP archaeologists have found evidence of blacksmithing. The horizontal location given by Hope-Taylor corresponds closely with the area where they found the blacksmith.

The fire that caused the loss of the Bamburgh sword, whether from a local fire around the blacksmith’s forge or a more general conflagration, did us the favour of ensuring that these old pieces of metal were forgotten and left to moulder in the ground until Hope-Taylor found them. But, from the way he had handled them, there was nothing to indicate that Hope-Taylor realised that they were anything out of the ordinary: just a few pieces of old and rusty metal.

It was Paul’s gut intuition that these bits of metal were special that had led him to call on the Royal Armouries in the first place. And when Dr Starley eventually called back, he confirmed that Paul’s instinct about these bits of battered metal had proved absolutely correct. Both swords had been pattern-welded weapons of the highest quality. Pattern welding was how smiths attempted to compensate for impure iron. They took billets of different iron, forge welded them together, and twisted them, producing the patterns characteristic of pattern welding.

The broken sword with both halves was a pattern-welded blade made from four billets of iron, which put it on a par with the sword excavated from the burial mound at Sutton Hoo in 1939. While the identity of the man buried in the ship at Sutton Hoo cannot be established with complete certainty, the most likely candidate was Rædwald, king of East Anglia, and, at the time of his death in the early seventh century, the most powerful king in Britain. So, the broken sword that Hope-Taylor had excavated but put away was a weapon of comparable quality to that wielded by a king.

But the other sword – the one of which only half was found – had been even better. According to Dr Starley, it was forged from six billets of iron, pattern welded together. It would have been a sword of incomparable quality, truly a sword that might have been wielded by kings. Stylistically, the sword was created in the early seventh century. The deposition layer from which Hope-Taylor had excavated it gave a date in the 10th century. Since it was unlikely that a broken sword would have been kept for hundreds of years,* the sword must have been handed down through the generations as both an heirloom and a potent and powerful weapon.

As for the axe, on any ordinary site, it would be special. It was the head of a broad axe, scarf welded and used in the construction of boards and planks. Scarf welding is when two bevelled edges are welded together. This type of axe is still used in shipmaking today. But the axe paled in comparison to the swords.

As Paul listened to Dr Starley, he realised that these weapons were truly extraordinary. The complete but broken sword was a match to the highest-quality blade yet found in Britain. The half sword stood in a category all of its own. Dr Starley was telling Paul that he had never before examined a weapon of such quality. No one had yet discovered a sword made from six billets of pattern-welded iron. It was not just extraordinary, it was unique.

As the telephone call finally ended, Paul sat down, almost winded by what he had been told. According to the archaeometallurgist of the Royal Armouries, the BRP had unearthed two of the finest swords ever forged.

But in archaeology, context is everything.

With Dr Starley’s dating putting the forging of the weapons in the first half of the seventh century, Paul could start to put the creation of these weapons into context.

In the seventh century, Britain was a patchwork of warring kingdoms. In the seventh century, Britain was on the outer edges of the known world, a long way from the centres of power and wealth clustered around the shores of the Mediterranean and in what would become France. In the seventh century, Britain was just emerging from two centuries when it had slipped from the pages of history and had become a place of legend and song.

The Roman veneer of four centuries of Imperial rule had been gradually rubbed away and, in its place, was a country of mead halls and small villages with few centres of population larger than a small town. The urban life of the Empire had slowly disintegrated as the bureaucratic, military, economic and political systems that made it possible withdrew. There is increasing evidence that parts of the major cities continued to be inhabited well beyond the end of traditional Roman rule, but the absence of the knowledge and resources of the Empire led to dwindling pools of artisans, materials and technology.

The Saxons, invited in as mercenaries, had stayed and started carving out kingdoms for themselves. Britain became a country of petty principalities, a patchwork of volatile gangster kingdoms where the rulers’ writ ran no further than a few villages: a shire was a large realm in the fifth and sixth centuries. The literate culture of the Empire had been entirely lost in the parts of Britain where the Angles and the Saxons and the other Germanic adventurers held sway, although it clung on in Old Britain, in the valleys and islands of the west and the north. It was a place where the clichés of later medieval life – that people never ventured far beyond their own village – might have actually had some basis.

So, as Paul sat turning over the implications of the news, he started thinking on how a smith at the edge of the world, in a preliterate society, might have forged two of the finest swords ever made. Where did he get the knowledge? How did he get hold of the materials? Who supported and paid for it all? For make no mistake, weapons such as these would have taken hundreds of man hours to create.

The historical sources are no help. For the whole of the fifth and sixth centuries in Britain we have so few contemporary historical sources that you can count them on one hand: a theological jeremiad against the contemporary rulers of the Britons by an irate monk named Gildas and a couple of letters from St Patrick. There are a few passing mentions of Britain in other documents and that’s it. The seventh century slowly returns to some sort of historical record, mainly thanks to the work of Bede and the laconic comments of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, but neither source pays much attention to the working of blacksmiths.

To find out how an anonymous blacksmith at the edge of the known world had made these swords, Paul would have to dig: into the archaeology, into the new scientific techniques opening up the artefacts of the past and, finally, into the making of swords.

Sometimes, when the historical record is silent and the archaeology incomplete, a question might only be answered by setting out to do what people in the past had done. The most famous examples of this have been ocean voyages, such as Thor Heyerdahl’s Kon-Tiki expedition by raft across the Pacific and Tim Severin’s Brendan expedition from Ireland to Newfoundland. But experimental archaeology has expanded hugely over the last 50 years, taking in activities as varied as recreating Roman cement that sets underwater, erecting a monumental standing stone and moving bluestones across hostile terrain using rope and sled. Paul himself worked as part of a team recreating Maelmin Henge in Northumberland with Neolithic technology. While they did the building, the team all lived in a Neolithic camp, ate Neolithic food, wore Neolithic clothes and used Neolithic tools. In this expansion of experimental archaeology – which we can define as the recreation of the objects and activities of the past using the tools, techniques and materials that would have been available at the time – the archaeologists have been aided and sometimes followed in the wake of another rapidly growing field: historical re-enactment. Indeed, the best historical re-enactors often have an encyclopaedic knowledge of their era coupled with a practical knowledge of the materials and objects of the time that it is difficult for an academic archaeologist to match.

To investigate how these swords were made, Paul realised he was going to have to learn how to forge a sword. And not just forge, but how to find iron and smelt it, how to build a furnace, and how to shape hot metal with hammer and anvil.

It really was better than an office job.

* Although, in The Lord of the Rings Aragorn’s sword, Narsil, was handed down through the generations as a symbol of sovereignty even though the sword was broken, so it is conceivable that a broken sword might become an heirloom of a royal house. While Middle-earth is, of course, the product of J.R.R. Tolkien’s imagination, the good professor was the foremost authority on Old English during his lifetime, and we would not be at all surprised if his informed imaginings had some parallels in the actual history of Anglo-Saxon England.

PART ONE

The Evolution of Swords

Chapter 1

What Is a Sword?

One laconic answer would be a long pointy thing for stabbing and slashing. It’s a facile answer, but it also highlights the two distinct aspects that make a sword what it is, and it hints towards what makes the sword unique among weapons. Firstly, saying a sword is a ‘long pointy thing’ speaks of its physical nature, its form (long and pointy) and its material (‘thing’, so it is an object that is made of a specific material).

The Greek philosopher Aristotle argued that ‘men do not think they know a thing till they have grasped the “why” of it (which is to grasp its primary cause).’* Aristotle then went on to say that there are, in fact, four causes – and answers to all those causes are required to fully understand something. The views of a man who lived nearly 2,500 years ago might not seem relevant today, but we are not dealing with a weapon of today. The sword arose from history and metallurgy, and Aristotle was a teacher as well as a philosopher. Among his pupils was the son of Philip II, king of Macedon. The boy was named Alexander, and the man Alexander burned through the world in a decade, his cavalry wielding a single-edged slashing sword called a kopis. Aristotle started teaching Alexander when the boy was 13, the king having given Aristotle the Temple of the Nymphs in Mieza as his schoolroom. Alongside Alexander the Great, Aristotle taught many of the heir’s young friends who would go on to become the nucleus of Alexander’s ‘Companions’, the group of talented generals and soldiers that formed the early core of his conquering army. Being a Peripatetic philosopher, literally one who taught while walking, it’s easy to imagine Aristotle beating out his ideas in time with his stride, quizzing his charges as they scurried after him, demanding of them the clarity of thought necessary to determine the four causes of a thing.

The four causes are material, formal, efficient and final.

In the case of a sword, the material cause is what the sword is made of. In the time of Alexander, swords were made of iron. The creation and history of swords is bound inseparably to the story of the materials from which they are made: the two will twine together throughout this book.

The formal cause is the shape, the design of the thing. In the case of a sword, it is indeed a sharp-edged, usually pointed object with a handle. But the exact form of swords has varied immensely throughout their history. Indeed, while swords are hard and unyielding, their form has been immensely reactive to the circumstances in which they are being wielded. In fact, the weapon that has carved out empires has proved to be uniquely responsive to its environment in a way that outstrips other weapons and tools.

The efficient cause is the agent or action that brought the thing to be. In the case of a sword, it is the smith – but the smith understood in the wider sense, including the smelter who refines the ore into the iron to make the sword, and the various craftsmen who made the hilt, finished and sharpened the sword, and made the scabbard.

The final cause is the purpose and the end, the ‘why’.

The purpose of the sword is to kill.

That is what swords do. It is their why.

In this, the sword is unique for it was the first human tool whose only purpose was death. The battlefield weapons that existed before swords were all repurposed tools used also in hunting, carpentry, skinning, all the myriad skills that our ancestors employed to live in a hostile world. This is not to say that the prehistoric, pre-metal-working past was some prelapsarian idyll where gentle hunter-gatherers picked a ripening crop of berries in between spearing the running salmon and raiding beehives. Mankind has waged war through history and deep into our evolutionary past, repurposing peaceful tools into killing weapons to fight better.

But the sword was the first human tool specifically made for killing other human beings.

The sword’s history is not limited by region. Every culture that has developed the necessary skills to smelt ore into metal has made swords. Some of these civilisations were very widely spread, and it remains an open question whether swords were independently invented in different places, whether they spread through a process of trade, conflict and conquest, or by a mixture of both. Wherever they have been used, swords have filled a roughly similar role as a sidearm, a personal weapon that can be employed individually and as part of a military formation. This perhaps gives us a clue both as to why swords became ubiquitous and how they arose in distinction from knives.

But before we go further, we must admit that there is no universal definition to separate a knife from a sword. Particular cultures have definitions – by style, size and usage – to distinguish the two, but in all cases the definitions are products of the culture and the uses to which swords and knives are put within that society. In some contexts, the distinction becomes blurred. For instance, a machete can function as knife, sword and tool, a human instrument that is marvellously responsive to the needs of a culture living within the rapid-growth forests of east Asia. But nonetheless, in most societies, knives and swords are distinguished.

The difficulty is to separate the sword from the knife. The answer must be social, functional and practical. On the social level, swords became the distinctive tool of the military caste, of the artisans of war. As a sidearm, swords could be carried around everywhere in a way that other weapons – in particular, the variations on spears that probably did most of the actual killing in ancient warfare – couldn’t. Greek hoplite spears were simply too long to carry around regularly, while the sarissa used by Alexander’s phalanxes were even longer – between four and six metres – and had to be carried around in two sections and joined before battle. Thus, the portable and wearable sword became the mark of the soldier and, by extension in a time of conquest and empire, one of the symbols of the ruler. The sword, as elite military tool, was then distinguished from the knife by its length, its placement in a waist scabbard and its decoration. Knives were utilitarian items with minimal decoration, whereas swords could be richly decorated indeed.

On a functional level, swords were used distinctively from knives depending upon the military tactics of the units bearing them. From the xiphos of the Greek hoplites (similar to Bilbo’s Sting) to the short-bladed gladius of the early Roman legionary, to the longer spatha of his late-Imperial successor, to the swords of the early and high medieval periods, swords were used to pierce and slice the enemy within the context of the war-fighting style in which they were employed. The sword was again distinguished from the knife by the military tactics of the time. Within the context of ancient warfare, where the spear in its various forms was the main weapon, the sword also functioned very well as an all-purpose secondary weapon: it was portable, wearable and long enough to keep the enemy at bay while being short enough to do the dirty work of short-range killing.

Finally, at a practical level, contemporary experimental archaeologists and martial arts practitioners have pointed out a fundamental difference between knife fights and sword fights. In a knife fight, it’s likely that even the victor will be injured. It’s a function of the close-range nature of the weapon and the accompanying fighting: to strike with a knife requires getting to within such close range that a counter-strike is likely and very difficult to block or avoid. Two men fighting with swords, however, will maintain greater separation. Even when attacking, they will generally be further apart. While a sword can cause catastrophic injuries with a single blow in a way that a knife usually cannot, such injuries also end a fight very quickly, likely leaving the victor relatively unscathed. Thus, when comparing a knife fight to a sword fight, while the probability of very sudden violent death is higher in a sword fight, the odds of getting out of the contest, if you survive, without life-crippling injuries are also greater when fighting with a sword. Where the wager is one’s life, you would have to be a very confident and skilled knife fighter to prefer fighting with a knife.

As always, there are exceptions and the 19th-century American pioneer Jim Bowie was one such exception, and an example of what a skilled knife fighter can do. In the infamous Vidalia Sandbar fight of 1827, Bowie, armed only with the knife that would cement his reputation, fought five or six armed men. He was shot several times, hit over the head with a pistol so hard that it broke and stabbed with a sword cane. Despite his injuries, he killed one man with his knife and wounded at least one other, with the remainder making a rapid, tactical withdrawal. In this case, the knife fighter had forced the larger, better armed party to retreat.

Because sword fights occur at longer range than knife fights, disadvantages of size and strength count for somewhat less. A close-range knife fight will, in grim reality, have as much wrestling, gouging, butting and other forms of close combat as actual knife play, giving the bigger, stronger man a considerable advantage. But with swords in hands, speed and skill come to the fore and while they won’t cancel out disadvantages in size and strength, they compensate more for their lack.

So, while there is no magic formula for distinguishing between knives and swords, societies employing both – which is pretty well all societies that have developed beyond their Stone Age – have generally had no difficulty in telling swords apart from knives.

However, the sword as weapon, a tool of warfare, exists on other levels than the practical. It is far more than the sum of its parts. A sword is a signifier, an indicator of rank, power, prestige and potential martial prowess. A man (or potentially a woman) with a sword has the wealth and status necessary to ensure access to a good diet, leisure time to train, a psychology that is suited to fighting, and the will to use it. A person carrying a sword also carries the threat of a sword, usually far more important than the sword itself. Dead people cannot plough and plant, so it was far better to convince via the threat of a sword than to actually use it.

And as we get deeper into the concept of the sword, we will see that they often carry names and bear legends, manifestations of previous battles won and deeds done. A sword has a history, and this is as precious to the owner as the beaded strings of wampum to the Iroquois or the medals on a modern soldier’s chest.

* Aristotle, Physics, 194 b17–20. Translated by R.P. Hardie and R.K. Gaye. Online at http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/physics.2.ii.html. Last accessed 12 April 2022.

Chapter 2

The Prehistory of Swords

While swords are the oldest tool designed exclusively to kill, human violence predates the invention of the sword. Diving deep into evolutionary history, it predates our emergence as modern Homo sapiens sapiens. There are examples of Neanderthals and earlier hominids whose skeletons bear the marks of violent death – although without further context it is not possible to state definitively that they were killed by another member of their own species. However, studies of the battles fought between rival groups of modern primates indicate that intra-species violence has deep roots within our lineage.

There are, however, some cases where death was indubitably caused by human action, and among these perhaps the best known is the Iceman, or Ötzi. His body was found on Th ursday 19 September 1991 by two German tourists, Helmut and Erika Simon, in the Ötztal Alps, which straddle the border of Austria and Italy. The Simons were walking on the glacier covering the high levels of the Fineilspitze peak when they spotted the head and upper torso of a body protruding from the ice. The body was high up – 3,210 metres above sea level – and the Simons assumed it was that of a climber previously lost on the mountain. The discovery was reported to the Austrian police and the Italian carabinieri and, the next day, the Simons led a party to the body and, entirely unaware of what they had discovered, they set about trying to dig the body out of the ice, hacking away with spades and picks. However, Ötzi was too deeply buried and it proved impossible to dig him out.

Ötzi’s body was finally freed from the ice on Sunday 22 September. He was dug out with icepicks while a camera crew filmed. Unfortunately, much of the context that would have given further valuable information about Ötzi was lost during his exhumation. Ötzi’s body, as well as the objects found on and around him, was taken to Innsbruck in Austria and, on 24 September, an archaeologist from the University of Innsbruck, Konrad Spindler, examined the body and estimated it to be around 4,000 years old.

Ötzi was clearly a sensational find, which begged the important question of to whom it belonged. Ötzi’s body was very close to the border between Italy and Austria. Obviously, in the Alps, there is no border fence, so the question had to be settled by establishing the find site exactly and then checking that against the border between Italy and Austria. While Ötzi had been taken to Innsbruck in Austria, careful measurement of the find site showed that he had been found 92.56 metres inside Italy. After discussions, it was agreed that Ötzi would eventually return to Italy, but since he was already in Austria the initial archaeological examinations would continue there.

With Spindler’s identification of the body as ancient, more measured and properly recorded excavations of the find site were undertaken in September and October, revealing string, a part of a grass mat, bits of hide and birch bark. Winter comes early at that altitude in the Alps so a full excavation of the site could only be undertaken the following summer, in July and August 1992, when Ötzi’s bearskin cap was discovered.

At first, it was assumed that Ötzi had died from exposure, caught up on the mountains in a storm and then buried beneath the snow. There was so much of interest about Ötzi, his clothes and his tools that it is not surprising that the cause of his death was not appreciated at once. It was as if a traveller from 5,000 years ago had come into the present, unable to speak our language, but by his presence and the things he carried, he bore a message from our past.

Ötzi was well equipped for his passage through the Alps. When he died, he was wearing a grass-woven cloak and a coat, leggings, a loincloth, shoes and a bearskin cap. Apart from high-altitude clothing, he also had a backpack, a quiver holding arrows fletched and unfletched, a bow, two birch baskets, a flint knife and retoucheur tool, and a copper axe. The copper axe draws most of the attention but a careful look at the knife has revealed a window into the world of flint tools.

Ötzi’s flint dagger was bound into an ash-wood handle with animal sinew. However, the dagger was considerably shorter than the sheath, made from lime tree bast, in which it was carried. But when the dagger was first placed into the sheath, it would have fitted.

Flint flakes. It flakes along shear lines, leaving the sharp edge that made flint a tool. Flint knappers working today can turn a lump of rock into a thoroughly serviceable knife in 10 or 20 minutes. Flint knappers in the past must have been at least as skilled and likely far more so: it was their life work. Ötzi’s knife looks like it was first made for him by a highly skilled flint knapper, but Ötzi then regularly sharpened it, chipping away further flakes of flint, sharpening but shortening the blade.

It is often assumed by the uninitiated that prehistoric flint knappers used other pieces of flint to shape their tools, but among Ötzi’s tool kit was a stick from a lime tree, 12 centimetres long, with the bark stripped off and shaped like a pencil. A spike of antler had been hammered into the stick, just like the lead in a pencil. The antler itself had been hardened in a fire. The end of the lime stick was shaped in a cone with the end of the hardened antler protruding from the centre – it looks exactly like a 5,000-year-old pencil that wants a fresh sharpening. As a composite tool, it was completely new to archaeologists – not surprisingly, perhaps, since wood and antler don’t endure in the way that flint and pottery do. This unexpected tool provoked much head-scratching until further analysis revealed microscopic traces of flint on the pointy head of the stick. It seems that Ötzi used the pencil to shape and sharpen his flint tools; the antler ‘lead’ was also sharpened when it became blunt, just like a pencil. The tool was named a retoucheur in French, which sounds much better than the English ‘retoucher’, and it has revealed a technique of flint-working that was previously unknown to us. But for the people of Ötzi’s time, flint-working was a mature technology of which everyone knew the basics.

However, it was Ötzi’s axe that, not surprisingly, drew the most attention. The axe is intact and unique. Made from 99.7 per cent pure copper, the head was stuck to the 60-centimetre yew-wood haft (handle) with birch tar, which glued the copper axe head into the fork of the haft, and then bound tightly in place with leather thongs. The leather was originally wound on when wet. Rawhide is much more flexible and pliable when soaked. It then contracts as it dries, forming a rigid, strong bind. There are no other surviving axes of this type, and certainly none with all the perishable fixtures still intact.

Ötzi’s axe was as pure an example of the Copper Age as might be found. The Copper Age was when the first metal tools and weapons were spreading out from their origin in Asia Minor into Europe and Asia. And they spread with the usual human accompaniment of violence and killing.

For 10 years after his discovery, Ötzi’s death was ascribed to exposure in the mountains. But in 2001 a CT scan and X-rays showed that Ötzi had an arrowhead in his left shoulder. Further examination of his body showed cuts to the hands, wrists and chest, bruises and evidence of Ötzi having been hit on the head.

It seems that the Iceman had been killed.

In 1999, Paul spent three weeks living a Neolithic life. He was part of a team reconstructing the Maelmin Henge in Northumberland using only the tools that would have been available at the time, wearing Neolithic clothing and eating a prehistoric diet. Paul lived in a rudimentary shelter that he had made himself. His clothing was based on what Ötzi wore: leggings, loin cloth, leather shoes, deerskin shirt. For three weeks, Paul ate a prehistoric diet, lit the fire with a bow drill and dug a henge using antler picks and scapula spades. He used a hazel twig toothbrush, drank heather beer from homemade pottery. There were no modern intrusions at all. It was also the wettest April on record. Having field-tested Ötzi-style clothing in such conditions, Paul can attest to its quality: it kept him warm and as dry as was possible when the world had turned to mud.

Maelmin Henge is just two miles north of the site of Ad Gefrin, the great Northumbrian hall and amphitheatre that Brian Hope-Taylor excavated in the 1950s. The wielder of the Bamburgh sword would have ridden past the remains of the original henge many times, in peace and in war.

Centuries before, Ötzi too would fall victim to the dark forces in the human soul that have driven conflict from long before recorded history began. Flint, plentiful and ubiquitous, was worked into weapons such as knives, arrows, axes and even daggers of six inches or so in length – flint, being brittle, is unsuited for long knives, although an 18-inch flint sickle has been found, indicating that flint tools could reach surprising lengths. However, in a battle, a stout lateral blow from a stick is as good as guaranteed to snap a long flint weapon in half. A flint sword, given the limitations of the source material, was always an impossibility, even if the idea of it ever occurred.

But before the sword of the hand could be invented, mankind had to develop the sword of the mind. Why would this be necessary? A sword is self-explanatory: a long blade for cutting and piercing people. But the sword as a martial tool does not exist in isolation. Swords evolved in lockstep with developments in culture and advances in technology, developments that gave birth to the sword and which the sword also served to foster.

And swords are made in specific ways; they are used to carry out particular acts, and they are wielded by a separate caste of people. All of these ingredients have to come together to create the concept of a sword.

The final requirement for the evolution of the sword was the enemy. Swords developed once our enemies became human beings. If you are fighting a bear or a lion, a sword is not the ideal weapon as you have to get in close – and close to an angry bear is not a good place to be. Far better to use a long spear to maintain distance. But fighting another man – that is personal. Over the last few centuries, we have developed increasingly ranged weapons so that now our killing is done at a distance, but for the greater part of human history, killing was done up close: warriors saw the soul strings cut from the body.

For the vast majority of people, killing is something that has to be trained into them. While a desperate struggle to defend family and farm against bandits is something that most men could and would do if required, the premeditated killing in battle of another, and another, and another – and the self-control necessary to enter into battle – has generally been reserved for a particular caste and class of people: the warriors.

One of the markers distinguishing the warrior caste from the rest of society was its almost universal practice of hunting as leisure pursuit. Hunting provided training in many of the tactics and techniques of warfare, it inculcated courage and strength, and it habituated the hunter to killing. As such, hunting provided vital training to new warriors and helped maintain the fitness of experienced warriors.

While hunting was the characteristic leisure pursuit of the warrior caste, swords were the personal weapons of warriors. Swords have been the characteristic weapon for the warrior caste for most of its history and in most places. There are exceptions: the modern officer class, the warriors of the Americas and the Zulu warrior caste among them, although the assegai was used in an almost identical way to a sword. The Zulu king Shaka introduced the short stabbing spear, the iklwa, to make his warriors fiercer and their close-quarters, hand-to-hand combat more effective by giving them weaponry that cannot be thrown, only used like a sword. However, for the most part, the sword was the weapon of the men who commanded other men in battle. That’s obviously not to say that the ordinary soldier/warrior did not bear swords, nor that battle leaders did not use other weapons, but the sword was the weapon born by the men who, in one of the first major social divisions in prehistory, were able to forswear labour in the fields for the duty of protecting the farmers from marauders and invaders. The sword became a badge of rank and a symbol of power and prestige.

Since the earliest swords were made at a time when metal was still a scarce and precious resource, the men wearing swords were also marked out as wealthy and powerful, the protectors of the realm. The sword was a product and a catalyst for the stratification of the first settled, farming societies, as well as a product of and a catalyst for the development of smelting and forging of metal, from copper to bronze to iron.

The first prerequisite for the sword, in hand and in mind, was the expansion of the population. Nomads regulate childbirth, mainly by continuing breastfeeding past weaning so that a new pregnancy does not begin until the previous baby is able to walk on its own. It’s possible to carry one babe in arms from place to place: two is too many. But farmers need hands for labour: there was an incentive to have more children, and one person can look after ten children in a house and garden, which is an impossible situation for nomads. The main check on numbers became the ability to feed children, but that was offset to a large extent by having more hands for work.

The population of nomadic peoples also had to be kept small to allow easy access to resources. In a small group, marriage within the group is difficult, so exogenous marriage is imperative. This can only be done at specific times, such as seasonal gluts, which allow larger groups to form through harvest-based meetings. With the advent of domestication and farming, populations became large enough to permit enough variation within the population to allow marriage at any time of the year.

As such, it was possible for the population of the new human settlements that accompanied the first farmers to start rising quickly, producing people who not only had the incentive to protect their land but also a reason to invade other people’s land. But if a neighbouring group had a resource that you wanted, you could also trade for it. Trade was not confined to goods and resources: some of the earliest