15,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

In 1905 Georgia travelled to Chicago to study painting at the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1907 she enrolled at the Art Students’ League in New York City, where she studied with William Merritt Chase. During her time in New York she became familiar with the 291 Gallery owned by her future husband, photographer Alfred Stieglitz. In 1912, she and her sisters studied at university with Alon Bement, who employed a somewhat revolutionary method in art instruction originally conceived by Arthur Wesley Dow. In Bement’s class, the students did not mechanically copy nature, but instead were taught the principles of design using geometric shapes. They worked at exercises that included dividing a square, working within a circle and placing a rectangle around a drawing, then organising the composition by rearranging, adding or eliminating elements. It sounded dull and to most students it was. But Georgia found that these studies gave art its structure and helped her understand the basics of abstraction. During the 1920s O’Keeffe also produced a huge number of landscapes and botanical studies during annual trips to Lake George. With Stieglitz’s connections in the arts community of New York – from 1923 he organised an O’Keeffe exhibition annually – O’Keeffe’s work received a great deal of attention and commanded high prices. She, however, resented the sexual connotations people attached to her paintings, especially during the 1920s when Freudian theories became a form of what today might be termed “pop psychology”. The legacy she left behind is a unique vision that translates the complexity of nature into simple shapes for us to explore and make our own discoveries. She taught us there is poetry in nature and beauty in geometry. Georgia O’Keeffe’s long lifetime of work shows us new ways to see the world, from her eyes to ours.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 161

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

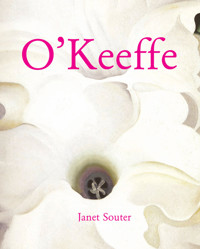

Frontcoverillustration

Belladonna-Häna,1939.

Oiloncanvas,92x76.2cm,

Privatecollection.

AuthorJanetSouter

Design:BaselineCoLtd

61A-63AVoVanTanStreet

4thFloor

District3,HoChiMinhCity

Vietnam

©ParkstonePressLtd,NewYork,USA

©ConfidentialConcepts,Worldwide,USA

©O’KeeffeEstate/ArtistsRightsSociety,NewYork,USA

©AlfredStieglitzEstate/ArtistsRightsSociety,NewYork,USA

ISBN:978-1-78310-747-6

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

JanetSouter

GeorgiaO’Keeffe

CONTENTS

Introduction

1887-1907Early Years: The Shaping of Georgia O’keeffe

1907-1916Finding Her Vision in the Emerging World of Modern Art

1916-1924“I’ve Given the World a Woman”

1925-1937The Stieglitz Years: Galleries, exhibitions, commissions

1938-1949An Artist in her own right

1949-1973The New Mexico years

1973-1986Artist emeritus

Biography

Bibliography

Index

Notes

PortraitofGeorgiaO’Keeffe.

INTRODUCTION

Georgia O’Keeffe, in her ability to see and marvel at the tiniest detail of a flower or the vastness of the southwestern landscape, drew us in as well. The more she cultivated her isolation, the more she attracted the rest of the world. What is it that makes her legacy so powerful, even today? People recognize flowers, bones, buildings. But something in her paintings also shows us how to see. We stroll on the beach or hike a footpath and barely notice a delicate seashell or the subtle shades of a pebble; we kick aside a worn shingle. Driving through the desert we shade our eyes from the sun, blink, and miss the lone skull, signifying a life long since gone. Georgia embraced all these things and more, brought them into focus and forced us to make their acquaintance. Then, she placed them in a context that stimulated our imagination. The remains of an elk’s skull hovering over the desert’s horizon, or the moon looking down on the hard line of a New York skyscraper briefly guide us into another world.

Her abstractions tell us that the play of horizontal and vertical shapes, concentric circles, curved and diagonal lines, images that exist in the mind, are alive as well and deserve to be shared. Georgia sensed this even as an art student in the early part of this century as she sat copying other people’s pictures or plaster torsos.

In her own life, she showed women that it was possible to search out and find the best in themselves; easier today, not so easy when Georgia was young. Her later years serve as a role model for those of us who feel life is a downhill slide after the age of sixty. Well into her nineties, her eyesight failing, she still found ways to express what she saw and how it excited her.

We look at her work and talk about it, but even Georgia had difficulty putting her thoughts into words. Her thoughts were on the canvas. What we can do in this book is see her evolution, who influenced her and how she forever sought out new experiences.

We cannot discuss these discoveries with Georgia O’Keeffe. Those days are gone. But if we look around, we can see that she still talks to us.

To this day, her work is as bright, fresh and moving as it was nearly 100 years ago. Why? Because, although the paintings, simple in their execution, hold a feeling of order, of being well thought out, a steadiness, yet a vehicle to help all of us see and examine the sensual delicacy of a flower, the starkness of a bleached skull and the electricity of a Western sunset.

GrapesonWhiteDish–DarkRim, 1920.

Oil on canvas, 22.9 x 25.4 cm.

Collection Mr and Mrs J.Carrington Woolley, Santa Fe.

1887-1907 EARLY YEARS: THE SHAPING OF GEORGIA O’KEEFFE

Georgia Totto O’Keeffe was born on 15 November, 1887, on a farm near the village of Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, the first daughter and second child of Francis and Ida Totto O’Keeffe. Her older brother, Francis Jr., had been born about a year and a half earlier. As an infant, Georgia already had a perception of lightness, darkness, brightness and had an artist’s eye for detail. Her first memory is from her infancy. She recalls being seated on a quilt on the lawn in front of the family farmhouse. Her mother sat at a table on a long bench. A friend of the family, known as Aunt Winnie, stood at the end of the table. Georgia recalls “Winnie’s” golden hair and her dress made of a thin white material. Years later, when she related the memory to her mother, Ida remembered that Georgia had been about nine months old at the time.

Georgia’s childhood was singularly uneventful. She spent her early and middle years on the large family home near Sun Prairie, an area of rolling hills and farmland. Wild flowers grew on either side of the dusty roads in the spring; the heavy sawing of cicadas could be heard on warm summer evenings; women gathered vegetables from the garden beneath a canopy of leaves in the fall and children delighted in sleigh rides over snow-covered fields in the winter.

Following Georgia’s birth, five other children appeared in rapid succession: Ida, Anita, Alexius, Catherine and Claudia. In the evenings and on rainy days, Ida O’Keeffe, believing in the importance of education, read to her children books such as James Fenimore Cooper’s LeatherstockingTales or stories of the West. Ida had spent much of her childhood on a farm next to the O’Keeffe’s property. When her father, George, left the family to return to his native Hungary, Ida’s mother, Isabel, moved the children to Madison, Wisconsin, where her children might have the opportunity for a formal education. Ida enjoyed pursuing her intellectual interests and as a young girl, thought of becoming a doctor. But when she reached her late teens, Francis O’Keeffe, who remembered her as the attractive girl from the nearby farm, visited her regularly in Madison and eventually proposed marriage. Isabel convinced Ida that Francis O’Keeffe possessed ambition and dependability, two excellent qualities in a husband. Ida liked Francis, although there was a history of tuberculosis in his family and people at that time avoided anyone whose relatives had died from the disease. Also, Ida was not enthusiastic about returning to Sun Prairie and its lack of cultural opportunities. Nevertheless, she listened to her mother, buried her ambitions, and on 19 February, 1884, became Mrs. Francis O’Keeffe. For the next several years, there was hardly a time when Ida was not pregnant or nursing. True, her husband worked tirelessly and they had a large home, but she was still a farmer’s wife whose education had been cut short.

She wanted more for her offspring and over the next several years, clung to the belief that if her children had the advantage of an exposure to culture, and a well-rounded education, it might keep them from falling further down the social ladder. She also felt it was important for her daughters to have the skills needed to earn their own living, should the need arise.

Ida had had some relief in the care of her children. Her widowed aunt Jennie lived with the family from the birth of the first baby. This left her time to pursue her own education, visit family in Madison, and occasionally enjoy the opera in Milwaukee.

From the time she was a tiny child, Georgia sensed that her mother favoured Francis Jr. and her more demonstrative sister Ida. This may have been why Georgia felt closer to her father, who she thought of as quite handsome. He always carried a little bag of sweets for his children and enjoyed playing Irish tunes on the fiddle. When a problem arose, he took it in his stride, and like most children, Georgia was drawn to the parent who made light of little mishaps. Ida, concerned with propriety and status, carefully monitored her children’s social life, seldom allowing them to play at their friends’ homes for fear they would acquire unacceptable social behaviour, or become sickly if they contracted the illnesses that spread around the area.

For nine years, Georgia walked to the one-room Town Hall schoolhouse, a short distance from her home. Perhaps because of the importance her mother had placed on learning, the thin, dark-haired Georgia with alert brown eyes was known to her neighbours and teachers as a bright, inquisitive little girl. In a typical child’s fascination with disaster, she once asked a teacher, “If Lake Monana rose up, way up and spilled over, how many people would drown?”

The oldest daughter in a family of seven children, Georgia became lost in the hustle and bustle of activity common in a large household. For Georgia, this meant she could enjoy unsupervised solitary play, creating “families” with her dolls. She once created a “father” by taking one of her “girl” dolls and sewing a pair of pants for him but was thoroughly dissatisfied with the result. She could not cut the long blond curls, because the stitching would show. In addition, the male doll was still fat, not the ideal image of an attractive, tall, lean man as head of a household.

The first picture Georgia remembers drawing was a man lying with his feet up in the air. “He was about two inches long,” she indicates in her autobiography, “carefully outlined with black lead pencil — a line made very dark by wetting the pencil in my mouth and pressing very hard on a tan paper bag.”

One can imagine a little girl hunched over her work, struggling with head and body parts, trying to show the man leaning over and wondering why the knees and hips did not seem to bend right. She wrote that after she had drawn the man bending at the hip, she turned the picture sideways and was delighted to see it worked when he was shown lying on his back his feet above his head. She always felt that she had never worked so hard before or since. Consistent with her desire for her children to have as many educational advantages as possible, Ida enrolled her daughters in drawing and painting classes in Sun Prairie during their elementary school years.

At first, they drew cubes and spheres to get the basics in perspective drawing. The following year, they took painting classes on Saturdays and were allowed to choose a picture to copy. Georgia remembers just two — one of Paharoah’s horses and another of large red roses. “It was the beginning with watercolor,” she later wrote.

Georgia attended the one-room school up until eighth grade. At the age of 13, she was talking with a washerwoman’s daughter about what they would be when they grew up. Georgia remembers saying, almost without thinking, “I’m going to be an artist.” To Georgia at the time it meant simply a portrait painter, having had little exposure to other art forms. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, few options were open to the woman seeking a career. She knew she could find work as a teacher, nurse, garment worker, governess, cook or housemaid.

If she were ambitious or from an upper class family and could afford the education, the law and medicine professions might let her in. As technology gained a foothold, she could be trained as a typist or telephone operator. In the world of art, a woman who attended a public art school went on to designing wallpaper, teaching, or commercial illustration. For most women, studying art was a stopgap pursuit to the ultimate goal — marriage.

Georgia began her high school years at Sacred Heart Academy, a Dominican convent near Madison. For her second year, she and Francis Jr., were sent to Madison High School and lived with their aunt in town. The school’s art teacher, a slight woman who wore a bonnet with artificial violets, gave Georgia her first insight into the mysteries and detail of the Jack-In-The-Pulpit flower. In her autobiography, O’Keeffe says:

“IhadseenmanyJacksbefore,butthiswasthefirsttimeIrememberexaminingaflower…IwasalittleannoyedatbeinginterestedbecauseIdidnotliketheteacher….Butmaybeshestartedmelookingatthings—lookingverycarefullyatdetails.”[1]

In 1902, suffering from ill health, Francis O’Keeffe moved his family to Williamsburg, Virginia, hoping the warmer climate would help him recover. His brothers and father had all succumbed to tuberculosis over the years, and Francis felt he could avoid the same fate in an area where the winters were not quite so harsh. Lured by brochures promising mild weather and reasonable land values, he moved his family east. For Georgia, this meant changing schools once again and for the next two years, she attended Chatham Episcopal Institute, a boarding school two hundred miles away. Unlike most children who might find this upheaval traumatic, Georgia did not seem to mind the school’s rules and rigid schedule imposed on her.

Within her large family, she was the quiet child people tended to ignore, and relied on her own resources for amusement. At Chatham, she enjoyed long walks in the woods, nurturing her love of nature, training her eye on a flower’s intricate details, and letting her gaze wander to the Blue Ridge Mountains in the distance.

If there was one teacher in her adolescent years who had a profound influence on Georgia’s life, it might have been Elizabeth May Willis, Chatham’s principal and art instructor. Tuned into Georgia’s inconsistent work habits, Willis let her student work at her own pace. And Georgia admitted years later, that Willis must have been frustrated with her at times, for the teenager sometimes refused to work and was often a disruption during class. Yet, when ready to create, she would stand by her easel for hours to perfect a painting, creating purples, reds, greens that amazed and impressed the other students. When the other girls complained that Georgia was never singled out for punishment because of her erratic behavior, Willis responded by saying that when she did work, she accomplished more in one day than the others did in a week.[2] One of the paintings that still exists is a still life called simply Untitled(GrapesandOranges), a watercolor in earth tones of rather dark green and ochre. The style is somewhat similar to the Impressionists, and shows her ability to work with color, light and shadow as well as displaying a mature drawing skill.

As for her relationships with the students in general, Georgia knew she looked somewhat odd to the others, whose frilly clothes and flirtations she ignored and never tried to imitate. Perhaps she chose black to rebel against her mother, who tried to remake her daughter into the image of a genteel young lady. Also, the family’s finances had dwindled and it is possible Ida could not afford to clothe her daughter in the same frilly dresses as the other girls wore. Nevertheless, Georgia’s schoolmates liked her and were impressed with her artistic talents. Although quiet and reserved, she joined in several school activities, including the basketball and tennis teams, the German Club and Kappa Delta, the social sorority. On the occasions when she did open up, she loved playing pranks. Once she pinned a bow to the back of a teacher’s dress, and for the school yearbook, drew extremely unflattering caricatures of the instructors. After teaching some of the girls how to play poker, she kept a game going for several weeks. Her schoolwork suffered because of her indifference to studying and she barely graduated in June, 1905.

The South at that time still held vestiges of pre-Civil War social order. The O’Keeffes were thought of as somewhat odd because they had no Negro servants, even though the family lived in a large home that Francis had optimistically purchased after selling the Sun Prairie farm. His grocery store did not produce much of a profit over the years, yet Ida struggled to keep up appearances and with her refined mannerisms desperately worked to fit into the women’s community, and to some extent, she did. She tried without success to have Georgia behave more like a southern lady. Her daughter’s plain way of dressing and her long solitary walks at dawn along the countryside paths, were hardly the lifestyle of a blossoming southern belle. To Georgia, what other people thought was unimportant; to keep peace, she obeyed her mother whenever possible and the rest of the time, kept to herself.

Following her graduation from Chatham, and encouraged by her mother and Elizabeth Willis, Georgia began to pursue her art career in earnest and in 1905 returned to the Midwest to study at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. At that time, it was unusual for girls to attend art school. Most Americans held fast to the Puritan ethic and the idea of sending a daughter to an institution that employed nude models was considered a threat to her moral upbringing. But Georgia had family living in Chicago, so in a sense she was not unsupervised. Two of her aunts and an uncle had a place not far from the school so she could walk to classes. One of the few remaining drawings she created at the time, titled MyAuntie, is of another aunt, Jennie Varnie, the relative who lived with the O’Keeffes and helped care for the children. Even then one can see that she had confidence in her ability to capture the essence of a person. Shading and texture form the tired eyes, firm mouth and tilt of the head. There are no inhibitions, no struggle with drawing the perfect line, common to young serious art students.

The Art Institute and its environment were a marked change from the rolling green hills and heady fresh air of the country. Now she strolled along crowded streets and breathed air full of soot and smoke as she made her way from her relatives’ apartment to the imposing Art Institute entrance, flanked by the famous bronze lions. During the first few months, her classes were held in the large galleries where she drew casts of hands and torsos. Later, in her anatomy class, she sketched in drab olive green rooms housed in the building’s basement. She was now exposed, so to speak, to the human figure. The story has been told several times of her embarrassment at the sight of a male model appearing from behind the dressing room curtain wearing nothing more than a small loin cloth.

Although Georgia never had an interest in drawing or painting the human figure, she did hold in high regard her anatomy instructor John Vanderpoel, a diminutive hunchback, yet one of the few teachers whose skill in drawing had a profound influence on her for years to come. In the auditorium where he lectured, she watched fascinated as his hand moved deftly over large sheets of tan paper, extending his reach as high as he could. His book, TheHumanFigure, was one she treasured throughout her career. At the end of the year, he gave Georgia’s drawings the first place award, and her overall record was stated as “exceptionally high.”