Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

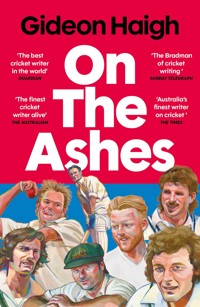

Nothing compares to the Ashes. The Ashes is always coming, even when it is finished. The Ashes is where hope, expectation, magic and chagrin flourish in equal measure, and performance is permanently burnished. 'The best cricket writer in the world' Guardian 'The Bradman of cricket writing' Sunday Telegraph 'The finest cricket writer alive' The Australian 'Australia's finest writer on cricket' The Times 'The most gifted cricket essayist of his generation' Richard Williams, Guardian In On The Ashes, Gideon Haigh, today's pre-eminent cricket writer, has captured over a century and a half of Anglo-Australian cricket, from WG Grace to Don Bradman, from Bodyline to Jim Laker's 19-wicket match, from Ian Botham's miracle at Headingley to the phenomena of Patrick Cummins and Ben Stokes, today's Ashes captains. From over three decades of covering The Ashes, Gideon has brought together an enduring vision of this timeless contest between Australia and England - the world's oldest sporting rivalry - from the colonial era to the present day.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 552

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Gideon Haigh was born in England and lives in Australia, with a parent from each. He was eight when he attended his first Ashes Test and twenty-four when he reported his first Ashes series. Gideon has written about cricket in The Australian, The Times, The Guardian, the Financial Times and in more than thirty books.

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2023 by Allen & Unwin, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2025 by Allen & Unwin.

Copyright © Gideon Haigh, 2023; 2025

The moral right of Gideon Haigh to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 999 9

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 998 2

Printed in Great Britain

Allen & Unwin

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Product safety EU representative: Authorised Rep Compliance Ltd., Ground Floor, 71 Lower Baggot Street, Dublin, D02 P593, Ireland. www.arccompliance.com

For Cee

Contents

Foreword

Golden Age, Darker Lining

Bodyline and Other Lines

Cricket’s Cold War

The Instant Age

Ashes Eyewitness

Index

Foreword

AN ASHES LIFE

The Ashes may have been in my stars. I was born in England, live in Australia, with a parent from each. I was eight when I attended my first Ashes Test, twenty-four when I reported my first Ashes series. I never intended becoming a cricket journalist, and would rather be considered a journalist who sometimes writes about cricket. But this collection, I’m bound to admit, makes an opposite case, collaging writings that cover almost a century and a half of Anglo-Australian cricket, people and places, news and olds.

Nothing compares to the Ashes, which in some respects is a shame, as this results from the lamentable abeyance in bilateral competition between India and Pakistan. But it is surely remarkable. After all, how many ideas endure from 1882, when creationism and phrenology flourished, nobody had heard of viruses or dreamed of X-rays, dreams of universal suffrage and a universal eight-hour day seemed fanciful, and cremation, of course, was a subject ripe for jokes? As the Empire sprawled mightily, the Australian continent was a mere patchwork of colonies reporting individually to faraway masters.

The Ashes has benefited hugely since by continuity, interrupted only by world wars, adulterated only by greedy administrators – I’m looking at those who inflicted ten consecutive Tests on us in 2013–14. The Ashes is always coming, even when it is finished. Especially in England, the intervening years are concerned with either soul-searching or brainstorming. There are, to be sure, bigger games in town. Indian visits line the vaults; World Cups gleam in the trophy cabinet. But the Ashes is where hope, expectation, magic and chagrin flourish in equal measure, and performance is permanently burnished. Ben Stokes at Headingley 2019 would have been a marvel against any opposition; its additional gilding is that it came at Australia’s expense.

Ahead of the Ashes of 2025–26, we find ourselves in a very particular period, where home advantage is bordering on the unassailable: Australia has not won a series in England since 2001, England not won a Test in Australia since 2011. But in a rivalry so long, everything can be deemed a phase. Even Bradman retired. Even Warne could be worked around. The Ashes, moreover, still connects. There is in marketing an established taxonomy of brands: the ‘ritual’ brand, identified with special occasions; the ‘symbolic’ brand, identified with a recognized logo; the ‘heritage of good’ brand, established as according a special benefit; the ‘aloof snob’ brand, nourishing a sense of superiority; the ‘belonging’ brand, which binds a self-perceived special group; and the ‘legend’ brand, which derives from an epic story. If it be possible, Ashes cricket works on all six levels.

But the Ashes is, of course, also more than a brand. Within it is the dynamic of rivalry, about which it is impossible to be neutral. I am not a particular patriot or partisan, except in barracking for Test matches: nothing so disappoints me as cricket that fails to rise to the occasion (such as, sad to say, the Ashes of 2021–22). But from my tangle of DNA and my hope for a worthy contest, I confess, arises a modest but unreducing satisfaction when England fares well. Australia is always competitive. They fight; they strike back. Since 1977, only once has Australia not won at least one Test in a series, and then, in 2013, they were about to whitewash England on home soil. This it is only possible to respect. It is England’s measuring up to and every so often exceeding Australia’s standard that completes the Ashes: their worst moments resonate uneasily with senses of national masochism and post-imperial marginalization. When these countries meet, in fact, there is always something slightly more at stake than cricket supremacy. They are saying something of themselves to the world.

What am I saying of myself? I grew up on anthologies of cricket writing: Pollard’s Six and Out, Ross’s The Cricketer’s Companion, compilations from sundry mastheads and about particular series, and particularly the canonical treasuries of Cardus, Robertson-Glasgow, Arlott, Swanton, Kilburn, Robinson and Fingleton. To curate my own collection is a happy act of homage, as well as an attempt to cover the full arc of history, from Charles Bannerman, the first Australian century-maker against England, to Ben Stokes, England’s most recent Ashes captain. I’ve had a press box vantage on the last three decades; by profiles, interviews, reviews and obituaries I’ve sought a communion with the past. I hope that the partialities of On The Ashes will be pardoned, that the gaps will be overlooked, and that the forthcoming cricket compels an updated edition.

GIDEON HAIGHMelbourne

GOLDEN AGE, DARKER LINING

Records are proverbially made to be broken; firsts stand for all time. Before the First World War, the Ashes was a blank tablet to carve feats into. So here are some of the carvers: the first scorer of a century, Charles Bannerman; the first taker of a five-for, William Midwinter; the first Ashes diarist, Tom Horan; the first giant series, 1894–95. The achievements have lasted as long as the lives associated proved short and benighted: Midwinter and captain extraordinaire Harry Trott became asylum inmates; Drewy Stoddart and Arthur Shrewsbury were suicides; Victor Trumper and Tip Foster, top scorers in the grand Sydney Test of 1903, were prematurely slain by illness; the whole belle époque would be drowned in mud, blood and disillusionment. But by 1914, the Ashes were established enough to survive, and nothing short of war has been equal to stopping them since.

The Ashes

SACRED SOOT (2017)

The Ashes fails almost every test as a modern sporting trophy. It confers no number one status, involves no massive cash prize and plods along in a slow-moving format widely considered obsolete. The small, frail urn would not catch your eye in a bric-a-brac shop, embodying the rivalry of a distant time, and riffing on a forgotten joke – about, for heaven’s sake, cremation. Although, considering what else was in vogue in 1882, England and Australia are lucky not to be playing for a trophy in the shape of Jumbo the elephant or the Eddystone Lighthouse.

In uniqueness, of course, lies the Ashes’ success. Aslant the priorities of contemporary sport, it occupies a universe of one. Its history can be exposited at voluminous length, or in a shorthand that summons legends by a name, by a year, or even by a single delivery, whether it’s Bradman b Hollies or Gatting b Warne. Better yet, success has exhibited a gratifying cyclicality: of seventy-two series, Australia have won thirty-four, England thirty-two, with six series drawn.

*

The totem’s origins are improbable – the fruit of youthful high spirits. When the fifth Anglo-Australian Test ended in a breathless seven-run victory for the visitors at The Oval, twenty-seven-year-old journalist Reginald Shirley Brooks secured immortality of a sort by inserting a death notice in London’s Sporting Times ‘in affectionate memory of English cricket’, with the addendum: ‘The body will be cremated and the ashes taken to Australia.’

Some months later in Australia, a twenty-three-year-old nob, The Hon. Ivo Walter Francis Bligh, who had come as captain of an English touring XI, referred jestingly to his objective as ‘recovery of the ashes’. The notion so captivated some Melbourne society belles, one of who became his bride, that they subsequently awarded Bligh a dark red pottery urn containing something sooty, popularly a burned bail, of which the Marylebone Cricket Club has been custodian since 1927. By then, the Ashes had gained a capital letter, thanks to the title of Pelham Warner’s journal of his team’s 1903–04 tour: How We Recovered the Ashes.

From the first, then, the Ashes has echoed and reinforced the relationship of the countries, playing out their differences in such a way as to emphasize their closeness. Perhaps only rivals with so much in common could afford such unbridled competition; at the same time, empire’s bonds never sat so heavily on the colonized because of cricket’s free play.

On a per capita basis, the Ashes has probably always meant more to Australians. ‘Cricket was the great way out of Australian cultural ignominy,’ wrote the novelist and republican gadfly Thomas Keneally. ‘No Australian had written Paradise Lost, but Bradman had made 100 before lunch at Lord’s.’ England’s frequent underdog status since the 1960s has also resonated with popular sensations of global decline, while also offering, every now and again, the salve of sporting superiority.

In the history of the Ashes, the decisive figure is Sir Donald Bradman, not merely because of his prowess, or his fame, or his statistics, but more generally the intensity his presence lent the contest. In piling up nineteen hundreds against England, he scaled the greatest heights; in provoking Bodyline, he engendered the most controversial countermeasures; in being knighted, he raised the cricketer to the level of imperial statesman. It helped universalize his popularity that Bradman was himself a conservative man, deeply respectful of the English institutions and assumptions he challenged. ‘We want him to do well,’ noted R. C. Robertson-Glasgow. ‘We feel we have a share in him. He is more than Australian. He is a world batsman.’

In our own generation, Richie Benaud and Shane Warne have achieved something like the same warm regard, Benaud by blending perfectly into the English media landscape, Warne by standing out from it with a certain irrepressibly comedic Aussieness. In the shadow of the unforgettable 2005 Ashes, a crowd at The Oval serenaded Warne with choruses of ‘We wish you were English.’ No sunhat has been so ceremoniously doffed as Warne did in acknowledgement.

Although it has been easier for Australians to win English admiration than the other way round, the panache of Ian Botham and Andrew Flintoff made them favourites. Some unexpected accommodations have also been reached. Grim Douglas Jardine and saturnine Harold Larwood were vilified through the Antipodes in 1932–33 as England rained bouncers on Australian batsmen. But the former returned as a tourist, remarking drily: ‘Though they may not hail me as Uncle Doug, I am no longer the bogeyman. Just an old so-and-so who got away with it.’ The latter was by then comfortably settled in Sydney, rather as if Mitchell Johnson was to become an English market town’s friendly greengrocer.

Issues have run the gamut, of course: from chucking to sledging, from doctoring pitches to conniving substitutes. The decisive weapon more often than not has been fast bowling, which tends to make blood pump and tempers flare. Yet it’s worth a small prayer of thanks for the extremities of competition being all in the one direction. There has never been an Ashes fix; there has never even been the thought of one. The cricket has been good and bad, exciting and dull, even-tempered and one-sided. But the only object has ever been winning or, failing that, avoiding defeat.

In this century, cricket has also been bent out of shape by economics, demographics and geopolitics; it has veered towards bigger markets and shorter attention spans, brighter colours and louder noises. Yet it remains the case that the biggest verified crowd for a day’s Test cricket anywhere, 91,112, was for the 2013 Boxing Day Ashes, on the same patch of earth where English and colonial teams met as far back as 1862. Bigger purses and greater prestige may be available elsewhere, but one joins no continuous cricket lineage longer or more meaningful. Bring it on.

Charles Bannerman

STANDARD SETTER (2016)1

Charles Bannerman is known today by a feat and an image. The feat, of course, is that of having faced Test cricket’s first ball and scored its first run before peeling off its maiden century, a match-winning 165 from an Australian all out score of 245 at the MCG in March 1877. The image is a widely published photograph taken nearly fifty-three years later of an elderly Bannerman, in hat and coat, laying a gently approving hand on the shoulder of Donald Bradman at the SCG, when the twenty-one-year-old was about to commence his near-vertical ascent through cricket’s hierarchy of records.

The time lapse between feat and image is perhaps just as evocative. Bannerman’s cricket peak was brief and lonely: you can almost argue that it was confined to that innings, when he took toll of an English bowling attack still queasy from a stormy crossing of the Tasman, for it was almost exactly twice his next best first-class score, and he played only two further Test matches. But a first can never be busted to second. Bannerman’s feat afforded him such imperishable status that he could, as it were, induct Bradman in an Australian batting lineage, with the additional prophecy: ‘This boy will clip all the records.’

The big gap is also an enigma, both enticing and off-putting to a potential biographer. Bannerman has probably waited as long as any cricketer for a historian to go searching for him, and Alfred James, a studious classicist, reveals the pressure of the years in Australia’s Premier Batsman: the traces are scant, limited and ambiguous. There are no photographs of Bannerman in action. The written accounts of his batting are disappointingly short of detail. James deems him a pioneer of ‘forward play’, but a mental image of his batting is hard to summon. Likewise a personal image. When James quotes a fond 1923 memoir of Bannerman from the journalist Jack Worrall – ‘May he long remain with us, with his big blue eyes and his lisp’ – the intimacy of the observation is powerful because it is so exceptional. Otherwise James is lumbered with reciting a great many scores, including some lengthy threadbare sequences, which seem a little redundant seeing that they’re recapitulated in statistical appendices.

Yet there is something here, and if the writing is mainly serviceable, with the occasional Latinate flourish, an intriguing story is hinted. Born in Woolwich, Bannerman was two years old when his family arrived in Sydney, his mother heavily pregnant with his brother Alick, himself destined to play twenty-eight Tests. Their father worked at Sydney’s Mint, whose deputy master was an accomplished round-arm bowler: the boys walked in, then, on an evolving game.

It was also the unruly game of an unruly people, and Charles Bannerman was no exception. James reveals that nineteen-year-old Bannerman lost his own Mint job for ‘insolence to his superior officer and general insubordination’, and went through a period in his early twenties when he alienated many contemporaries by his cocky club and colony hopping. ‘The colt was considered a bright particular star while he lasted,’ said a censorious columnist in the Sydney Mail in March 1874, ‘but a good many people have come to the conclusion that for some time he has been on the wane, and that if common sense does not come to his aid he will be snuffed out for ever.’ David Warner, then, has a distinguished antecedent. Although not even David Warner had three children with his first wife and two children with a mistress ten years his junior.

Bannerman’s crowded hour of glorious batting life came when he was twenty-five. After the subsequent Australian tour of England, he dropped away precipitously, in a way strangely foretold. And although James has been unable to establish any satisfactory explanation, writers seemed uncannily aware that the process was irreversible. By 1879, the Sydney Morning Herald was calling him ‘only the ghost of himself’, Australian Town and Country Journal ‘only the ghost of the player we used to know’, and the Sydney Mail was asserting that there was ‘no prospect of improvement’. Whatever they meant, they were right: for the next five years, Bannerman averaged less than 15 in first-class cricket. ‘Drink and gambling, it is reputed, was his downfall,’ wrote a contemporary many years later, although James shies from this ‘far-fetched conclusion on the slight evidence available’.

James being a reluctant interpreter, the reader is left in a way to build their own story. My own was this. Bannerman was unusual in his Australian era in playing openly as a ‘professional’. After losing his Mint job, he seems to have had only fragmentary employment outside the game: instead he relied on playing, touring, coaching and umpiring. His only other fallback, bookmaking, was a constraint. Not only did it eat into his Saturdays, but the England team of 1882–83 refused to accept him as an umpire – not surprising, really, given the betting-related cricket riot four years earlier when the SCG crowd stormed the field in protest at an umpiring decision against NSW’s Billy Murdoch during a game with Lord Harris’s Englishmen.

Bannerman was a ‘professional’, in other words, long before there was anything like a professional cricket structure. And for it he, and others, paid a price. Probably the most moving passages in James’s book are from a news story in Sydney’s Evening News, 27 May 1891, headlined ‘A Cricketer in Low Circumstances’: Bannerman had been arraigned to answer charges of desertion of his wife, and failure to provide for her. An exchange is recorded:

JUDGE: Your family is in destitute circumstances. How do you get your living?

BANNERMAN: By cricketing, your Worship.

JUDGE: But it’s the off season now, and there’s not much doing in that line.

BANNERMAN: I’ve nothing to say against my wife, your worship, at all. If you will give me a week to try and get the money, I might get some of it.

By cricketing, your Worship: four desperate words to encapsulate the precariousness of the professional cricket life, for the player, and for their financial dependents. Blessedly it was not to be the end. Cricket biography reserves a special place for the tragic figure. Bannerman ends up being a rarer figure in biography – a subject who flirted with tragedy and survived. When his wife died in 1895, he was able to marry his mistress, and he benefited by testimonial matches in 1899 and 1922; his prudent brother, meanwhile, grew wealthy.

In that 1930 photograph with bashful Bradman, Bannerman strikes a pose of solemn dignity befitting the prestige of his achievement – with maybe just a hint of the character he had been in his playing days. For is that a cigarette in his hand?

Tom Horan

FELIX ON THE BAT (2006)

In the last few weeks I have exchanged a number of emails with a young Indian, eagerly immersing himself in a dissertation on Australian cricket writing and full of questions. What did I think of Ray Robinson? Jack Fingleton? Peter Roebuck? (Peter will be gratified to know that he’s now seen as one of us.) I answered these enquiries as best I was able, then made my own modest proposal: if he was a serious scholar in the field, he should probably acquaint himself with Tom Horan.

When answer came there none, I was not especially surprised. If Horan rings a bell at all today, it is as a name in the very first Test in 1877, and on the Australians’ inaugural tour of England a year later, where he enjoyed the signal honour of the winning hit in their rout of Marylebone.

Born in County Cork on 8 March 1855 and brought to Melbourne as a boy, Horan became a steady top order batsman, worth 4027 first-class runs at 23, and considered good enough to captain Australia at a pinch in 1884–85 when more uppity teammates decided to hold out for a few extra shillings. By then, however, he had commenced a greater contribution to cricket’s common weal: the ‘Cricket Chatter’ columns in The Australasian, the weekly sister paper of Melbourne’s Argus, which he would compose for an extraordinary thirty-seven years. This transition was in its time highly unusual; in fact, distinguishing. Australian cricket was well supplied with competent scribes before the First World War, notably J. C. Davis and A. H. Gregory in Sydney, and Donald McDonald and Harry Hedley in Melbourne. Only Horan, however, had represented Australia, at home and abroad. There was no television to apparently drop the fan into the middle of the game; on the writer fell the entire responsibility for bringing the game to the fan, and no one in their time was on such intimate terms with cricket at the top level. It wasn’t merely out of Hibernian loyalty that Bill O’Reilly described Horan as ‘the cricket writer par excellence’; it was, he explained, because Horan was ‘a writer who really did know what he was writing about’.

‘Felix’, as he was pseudonymously known, was not an adventurous stylist: he wrote, instead, with his ears and eyes, with a sense of the telling remark and the evocative detail, such as in his recollection of his first encounter with Victor Trumper in 1897:

While on the Melbourne Ground the veteran Harry Hilliard introduced me to him and I was struck by the frank, engaging facial expression of the young Sydneyite. After a few words he went away and old Harry said to me: ‘That lad will have to be reckoned with later on.’ My word! But do you know what particularly attracted my attention when I first saw Victor fielding? You wouldn’t guess in three. It was the remarkably neat way in which his shirt sleeves were folded. No loose, dangling down, and folding back again after a run for the ball, but always trim and artistic.

I have never failed since to note this detail in Beldam’s famous image of Trumper jumping out to drive.

My own acquaintance with Horan dates from the early 1990s, thanks to Australia’s grand old man of cricket bibliophilia, Brisbane’s Pat Mullins. Horan was Pat’s great favourite, for his other great enthusiasm was all things Irish, and he had dedicated years of effort to compiling voluminous scrapbooks of Horaniana. When he foisted these on me at our first meeting, I accepted them with some reticence: seldom have I been so completely converted.

Horan knew everyone, and reported their deeds in a prose as breezy and inviting as his personality. When he is recounting the experiences of the English team of 1884–85 on tour, for instance, it is as though you have a seat at their table:

Barnes says that at Narrabri the heat was simply awful, and immediately up in the ranges at Armidale he had to wear a top coat and sit by the fire to keep himself warm . . . It would do one good to hear Ulyett, little Briggs or Attewell laugh as they detail some of their Australian experiences; how Flowers was frightened of the native bears on the banks of the Broken River at Benalla; how Ulyett jumped from the steamer on a hot afternoon on his way down from Clarence; and how little Briggs came to grief on a backjumper at Armidale. Briggs to this day maintains that the horse had nothing to do with unseating him, it was simply the saddle. His comrades, however, will not believe him . . . Briggs gives a graphic description of a murderous raid he made one night upon the mosquitos in Gympie, and how, when that proved futile, he quenched the light and pulled his bed into another corner of the room to dodge them.

In January 1893, The Australasian commissioned from ‘Felix’ a regular supplementary column called `Round the Ground’. Horan’s preferred vantage point at the MCG was under an elm tree near the sight board opposite the pavilion; from here he would embark on long peregrinations round the arena and through his memory, each personal encounter bringing forth a fund of reminiscences. It was during one of these ambles, in January 1902, that he committed to print perhaps his most famous passages, which concern the dying moments of the inaugural Ashes Test at The Oval in 1882 in which he had played.

Subsequently cited by H. S. Altham in A History of Cricket, these lines have been unconsciously paraphrased by scores of writers since:

. . . the strain even for the spectators was so severe, that one onlooker dropped down dead, and another with his teeth gnawed out pieces of his umbrella handle. That was the match in which for the final half-hour you could have heard a pin drop, while the celebrated batsmen, A. P. Lucas and Alfred Lyttelton, were together, and Spofforth and Boyle bowling at them as they never bowled before. That was the match in which the last English batsman had to screw his courage to the sticking place by the aid of champagne, when one man’s lips were ashen grey and his throat so parched that he could hardly speak as he strode by me to the crease; when the scorer’s hand shook so that he wrote Peate’s name like ‘geese’, and when in the wild tumult at the fall of the last wicket, the crowd in one tremendous roar cried ‘bravo Australia’.

That inaugural Ashes Test had, I suspect, another impact on Horan’s writing. He was not the last Australian journalist to be struck by the vehemence of the local criticisms of his English opponents:

The very papers which, in dealing with the first day’s play, said, in effect, that the English cricketers were the noblest, the bravest and the best; that, like the old guard of Napoleon, they would never know they are beaten, now turn completely around, and, with very questionable taste, designate these same cricketers as a weak-kneed and pusillanimous lot, who shaped worse than eleven schoolboys.

So even after his active cricketing days were over, Horan remained at heart a player: ‘Felix’ rejoiced in successes, and sympathized with failures, understanding sensitivities and susceptibilities as only one who has been there can. If he felt a point of order worth making, he did so with utmost even-handedness, the lightest touch and a peculiarly Victorian circumlocution.

‘All this should be enough, indeed, to make one long to be in possession of Cagliostro’s famous secret, so that one might have everlasting youth to enjoy to the full and for ever the glorious life of a first-class Australian cricketer,’ he wrote of the frequency of cricket tours in the 1880s. ‘Though, to be sure, one must not forget that the thing might pall upon the taste in the long run, for does not the sonnet tell us that “sweets grown common lose their dear delight”.’

No danger of that with Horan’s writing today; its sweetness remains well worth savouring.

Billy Midwinter

LOST SOUL (2015)

William Midwinter’s cricket career was full of firsts. He was the first bowler to take five wickets in an innings in a Test match. He was the first and remains the only cricketer to play for Australia against England and for England against Australia. But the first whose 125th anniversary falls today [3 December 2015] is that he was the first Australian Test cricketer to die, aged only thirty-nine, and in circumstances that caused Arthur Haygarth to remark in Cricket Scores and Biographies: ‘May the death of no other cricketer who has taken part in great matches be like his!’

Like the first Test centurion, Charles Bannerman, and the first number three, Tom Horan, Midwinter was an adopted Australian born in the UK. He was nine when his gamekeeper father brought the family from the Forest of Dean to California Gully, near Sandhurst, where he formed a lasting association with Harry Boyle, a precocious teenage medium-pace bowler who had organized a local team. He grew into a sandy-haired six-footer with a physique testifying to work as a miner and butcher. In the 1971 Wisden, the secretary of Gloucestershire CCC, Grahame Parker, published a superbly thorough account of Midwinter’s wanderings: how he came to the attention of his fellow Gloucester man W. G. Grace by bowling him and brother Fred at the MCG in March 1874; how he set off for England three weeks after the Second Test and became one of Grace’s cricket retinue; how when he tried to reunite with the Australian team of 1878, Grace regained his services by . . . well . . . abduction. He had in the meantime at least top-scored for the Australians in their astonishing turkey shoot-out at Lord’s: he made 10. The modern commuter cricket had nothing on ‘Mid’: to play six consecutive summers in Australia and England, he had to chalk up almost a year in travelling time.

What anchored Midwinter to Australia at last was love. In June 1883, he married a Bendigo girl, Lizzie McLaughlan, and became the publican at Carlton’s Clyde Hotel, then an eponymous hotel in South Melbourne, and finally the Victoria Hotel in Bourke Street. Lizzie bore a son in 1886, Albert, and a daughter and son in 1888, Elsie and William Jnr. At the end of that year, however, the Midwinters were struck by the first of a series of consuming family tragedies: infant Elsie died of pneumonia; within a year, Lizzie and Albert also died, and William Jnr was hospitalized with a crippling hip problem.

The effect on Billy Midwinter can be imagined . . . or actually, maybe it can’t All we really know is that while staying with a married sister back in his old neighbourhood of California Gully, Midwinter became violent, attempted self-immolation, threw candles at his hosts, and was found in possession of arms and ammunition – the police took him to Bendigo Hospital, from where he was decanted to Kew Asylum and designated ‘dangerous’. Within months, reported Horan in The Australasian, he had degenerated into a ‘helpless imbecile’.

The diagnosis of ‘general paralysis of the insane’ contained in his Kew Asylum records is unhelpfully vague. GPI was basically any neurological collapse the ‘alienists’ of the time could not explain: in William Julius Mickle’s comprehensive 1880 textbook, its causes ranged from emotional strain to an excess of alcohol or sex. Interestingly, the admitting staff at Kew conscientiously absolved Midwinter of the latter (‘Habits of life: Steady’) and stressed the former (‘Cause: domestic bereavement’). But later diagnosticians would establish a connection between GPI and untreated syphilis, and it’s possible that Midwinter’s infection was the unwitting cause of his family’s annihilation.

Whatever the case, he knew but one final brief lapse into lucidity, reported by the Singleton Argus:

H. F. Boyle went out to Kew (Vic.) Asylum one day last week to see his old Bendigo comrade Midwinter. The asylum authorities said that Midwinter would not recognize anybody, but, strange to say, he recognized Boyle, and also remembered W. G. Grace’s name when it was mentioned, and said, ‘Grace, good man.’ Dave Scott was also present, and Mid knew him too. When they left he relapsed into his condition of mental oblivion. His lower limbs are completely paralysed, and it is thought that he cannot live for another twelve month.

In fact, Midwinter did not live another week. His funeral was well-attended, the actress Maggie Moore, wife of J. C. Williamson, sending a bat composed of immortelles (everlasting flowers), which was placed on the coffin. But there was no money for a headstone, and the grave remained unmarked for almost a hundred years, until the plot was identified by the Australian Cricket Society. Richie Benaud used to balk at the use of the word ‘tragedy’ in the context of cricket, but this story might have satisfied his criteria: within twenty years of the first Test five-for, the man who took it, his wife and his three children were all dead.

W. G. Grace

THE GRAND OLD MAN (2022)

For W. G. Grace, the challenge of Test cricket against Australia materialized in the nick of time. In 1880, the nineteenth century’s greatest cricketer turned thirty-two. He was a father of three, had just become a doctor, and was committed for five years to a practice in a poor part of Bristol. For fifteen years, he had built a first-class cricket record beyond compare, averaging 50, producing more hundreds than almost all the rest of the world’s batsmen put together. What else was there to aim for?

In fact, Grace sensed the waft of change. The great travelling elevens of his youth were fading; the County Championship was formalizing; but above all there was competition from beyond the seas, which he had seen first-hand on his cricket tour cum honeymoon in 1873–74. Here was a rival worthy of his mettle, with whom he tangled again, and came off second best, at Lord’s, on that signal day in 1878 when Dave Gregory’s unheralded Australians routed Marylebone by ten wickets.

When the Australian team of 1880 arrived under the shadow of the infamous Sydney Cricket Ground riot a year earlier, they struggled to fill a fixture list until Grace, in consultation with the industrious Surrey secretary Charles Alcock, successfully pushed for a full-dress match at The Oval. It was so late in the season that Grace was almost on holiday. In the last week of August, he accepted an invitation to Kingsclere from John Porter, a leading horse trainer, to go shooting. Grace prepared for his Test debut with a social match against Newbury in which he took eleven wickets, made a catch and a stumping.

‘I came straight up to London for the Test match, and as I had not been playing in first-class cricket for some little time, I did not expect any conspicuous personal success,’ he recalled. ‘Nevertheless, I scored 152 out of the 420 made by England in the first innings.’ And, characteristically of Cricket Reminiscences & Personal Recollections (1899), that’s it: the only first-hand description of the first Test century by an Englishman.

This was not for want of trying from his amanuensis, the pertinacious Arthur Porritt, former editor of the Church Times, who undertook the blood-from-stone task of extracting Grace’s memories. It’s to Porritt’s own lively memoir, The Best I Remember (1922), that we owe some of the most incisive glimpses of Grace, ‘a singularly inarticulate man’ with ‘the simple faith of a child’ who disliked talking about himself and mangled every story yet was oddly magnetic: ‘He was a big grown-up boy, just what a man who only lived when he was in the open air might be expected to be. A wonderful kindliness ran through his nature, mingling strangely with the arbitrary temper of a man who had been accustomed to be dominant over other men.’

Thus, perhaps, Grace’s relationship with Australians, who shared his favour for the open air, while jibing at times with his tactless quest for advantage. ‘Thus, perhaps, was born the Whingeing Pom,’ says Simon Rae in W. G. Grace: A Life (1998) of that first fractious expedition down under. ‘I do not think it redounds much to any man’s credit to endeavor to win a match by resorting to what might not inaptly be called sharp practice,’ complained the Australian Tom Horan of Grace’s sly run out of Sammy Jones in the Ashes-making Oval Test of 1882. Yet Grace was no grudge holder in the vein of Lords Harris and Hawke. And for all his posthumous reputation for rapacity, the sense you obtain from the sheer density of Grace’s career, powerfully evoked by the 2000 matches enumerated in Joe Webber’s 1102-page Chronicle of WG (1998), is of a man who almost could hardly stop himself from playing cricket. No wonder he warmed to Australians: they meant he did not have to.

His Test figures provide a mean estimation of Grace: 1098 runs at 32.29 in twenty-two Tests spaced over nineteen years in this establishing phase of the format when teams were seldom altogether representative and administration was in constant flux. What’s notable in that, nonetheless, is the stimulus of rivalry. Grace’s 152 was immediately counter-weighted by the Australian Billy Murdoch’s 153 not out; having lost his English record score when Arthur Shrewsbury compiled 164 in the Test at Lord’s in 1886, Grace wrested it back with 170 in the Test at The Oval. Grace wasn’t about to share anything that day. No cricketer has rivalled the ratio of runs he scored while at the wicket in that match: a staggering 78 per cent. On the same pitch, Australia was bowled out for 68 and 149.

In that summer, Grace batted fifty-five times: a third of those innings were against Australia. By the end of his career, Webber tells us, he had packed in no fewer than 99 games against Antipodean XIs, with 4500 runs, 158 wickets and 111 catches – more than any other opponent. It was Australia, too, that persuaded Grace he was done: after the Trent Bridge Test of 1899, fifty-one-year-old Grace told his fellow selectors he was no longer worth his place. By then he was widely known as ‘The Old Man’. His girth was ample, his beard flecked with grey, his feet sore after a day’s play. In Life Worth Living (1939), C. B. Fry recounted Grace’s explanation at the fateful meeting: ‘It’s the ground, Charlie. It’s too far away.’

Nor did Australians forget. In The Old Man (1948), a biographical radio play on the BBC by John Arlott broadcast on Grace’s centenary, fellow commentator Alan McGilvray played the role of Billy Murdoch. Donald Bradman’s Australian ‘Invincibles’ sent a wreath to Grace’s half-ruined grave at Elmers End: ‘In memory of the great cricketer, from all Australia.’ ‘In W. G.,’ notes Grace’s latest biographer, Richard Tomlinson, in Amazing Grace (2018), ‘they recognized a fellow spirit.’ That might be regarded as putting a seal on the relationship: that, down the decades, Australians have played cricket more like Grace than his countrymen.

Billy Murdoch

WORLD CLASS (2019)2

Sometimes a book is published only for a late-breaking development to undermine a key assertion. Usually this is disappointing and frustrating. For the authors of a new biography of the Australian cricketer Billy Murdoch, however, the occurrence will be altogether welcome.

In Cricketing Colossus, to be launched today at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, Richard Cashman and Ric Sissons argue that Murdoch, maker of the first Test double-century and the first Australian first-class triple-century, should at once be inducted in the Australian Cricket Hall of Fame ‘to rectify more than a century of neglect of this great player’.

They were not to know that even as they wrote this the decision had been made to do so – by, among others, me – ahead of its announcement at Monday’s Australian Cricket Awards. Murdoch was indeed, as Cashman and Sissons argue, ‘the first Australian batsman to develop a world-class reputation’; maybe, also, the first captain.

Murdoch presented Australian batting credentials at the earliest opportunity, at The Oval during Australia’s inaugural Test in England, where W. G. Grace made 152, and Murdoch replied with 153 not out. His leadership spurs were gained on the same ground two years later when he led Australia to a first Test victory abroad, in the match from which emerged the Ashes tradition.

One of the reasons for his overlooking since, I suspect, has been the lack of a thorough biography – a service that, in Murdoch’s generation, Cashman has performed for Fred Spofforth and Sissons for Charlie Turner. And the reason for this is that Murdoch does not surrender readily to researchers: David Frith observes in his foreword, Murdoch’s ‘vacillating fortunes read like a novel’. He is a sporting Richard Mahony.3

Has any Australian cricketer had such an incomparably vivid patrimony? When American Gilbert Murdoch married Tasmanian Susanna Flegg in California in 1851, he was twenty-five and she was fifteen. Gilbert had been a corporal in a volunteer regiment from Maryland involved in the Mexican war and served as the second mayor of Monterey as part of a corrupt and violent Democrat clique; Susanna was the daughter of illiterate convicts, travelling with her mother and a consignment of goods on what was virtually a pirate ship.

No sooner had the newlyweds returned to Hobart than they embarked for the Victorian goldfields, where Billy would duly be born, and Gilbert become a flamboyant scapegrace, a merchant and auctioneer always on the edge of the law, eventually toppling in to jail in Bathurst and Beechworth.

Later profile writers drew a veil over Gilbert’s infamies, but Cashman and Sissons believe that he abandoned his family circa 1856, when Billy was an infant, and Australia just over a decade later. Returning to Monterey, he claimed that his family had perished in a shipwreck after which he had escaped from savages; setting up as a greengrocer, he contracted a bigamous marriage to an epileptic women thirty years his junior.

Of the impact on Billy, who can say? But there assuredly emerged competing parts of his character: a streak of entrepreneurship and tendency to improvidence versus an arriviste’s craving of respectability. This suited the Australian cricket teams he led between 1880 and 1884, which played with aggressively commercial intent while arrogating to themselves the status of amateurs. But it mainly showed up in his life, where he had an early brush with bankruptcy, then married money – or, to be more exact, eloped with it, hastily wedding a daughter of mining tycoon John Boyd Watson without approval.

In seeming atonement, Murdoch renounced cricket between the ages of thirty and thirty-five in favour of the life of a country solicitor, only resuming when old man Watson died – Murdoch promptly returned to Sydney, and was ceded the Australian captaincy for the 1890 Ashes tour. The team was a flop but the trip facilitated Murdoch’s relocation to England, whose leisure class his family joined, returning to Australia only twice in his remaining two decades.

Mind you, this outwardly cheerful and festive existence proved harder to sustain than the family let on. Cashman and Sissons have obtained some fascinating begging letters to the Watson estate, in which Murdoch’s wife touchingly if enigmatically defends his honour: ‘Other than his one little fault he could not be a better husband to me.’

Though Murdoch would play many years for Sussex, it also queered his Test career. In addition to his residence, Murdoch’s visiting South Africa with a team of English cricketers in 1891–92, including a match retrospectively accorded Test status, seems to have confounded his expectation of leading the next Australian team to tour England.

From Sydney, its manager Victor Cohen counselled Murdoch candidly that ‘there is a decided antipathy to the inclusion of any Anglo-Australians out here’. Murdoch’s retort was to call himself ‘an Australian pure and simple’. But his having to make such an insistence implied the opposite. It could be argued that he fell victim to prejudices he played a part in instilling, the achievements of Australian cricketers building a proto-national consciousness.

A year before his death in 1911, Melbourne Punch commented cattily on Murdoch’s diffuse allegiances: ‘The old cricket captain is thoroughly anglicized now, and regards Australia with horror as a little place set by itself as far as possible from everywhere else. He has become cosmopolitan, and cannot bear the thought of being more than a day’s journey from London, Berlin, Vienna, Paris, St Petersburg. That is the worst of a long and wealthy residence abroad, the best Australians becoming un-Australianized under such conditions.’

One hundred and nine years later, the fifty-second member of the Australian Cricket Hall of Fame is in a category with a membership of one: he is the first and only inductee to have also represented England.

George Giffen

ATLAS (2020)4

For eight decades, the George Giffen Stand was part of the patriotic topography of the Adelaide Oval, as distinctive and resonant as the Victor Richardson Gates. It was a fitting tribute. The cricketer for whom the stand was named was very nearly as permanent – a player who stopped only because it was impossible to play on one’s own, who had bowlers been allowed to bowl from both ends or batsmen been free to face their own bowling would have given nobody else a sniff.

Giffen, however, has been slow to achieve other recognition. The Chappells, Clem Hill and Clarrie Grimmett are the only other full-fledged South Australians in the Australian Cricket Hall of Fame. But Bernard Whimpress’s is the first biography, fully 122 years after Giffen published his own pioneering autobiography – the first of its kind, ghosted by Test cricket’s great taxonomist Clarence Moody.

The surname Giffen, Bernard tells us, emerged from Flanders. It is a coincidence, but an apt one, that some have posited Flanders as the birthplace of cricket, the name being an adaptation of a Flemish phrase for ‘to chase with a curved stick’. There is about Giffen, to be sure, something elemental and foundational. He took out the Australian patent on the all-round cricketer – classically defined as the player worthy of selection as either a batsman or a bowler. He was a cricketer, too, built to the specifications of timeless cricket, with a love of tall scores and unbroken spells, and an iron man’s physique. To the latter, Giffen’s contemporary Tom Horan paid sweaty tribute: ‘I saw him once in football rig at a fancy dress ball on board ship, and even the ladies paused to watch the muscular play of his finely developed arm.’

Giffen was also, in his way, a modern figure. He never married. He never had children. He travelled only for cricket. He stayed with the Post Office because it was amenable to his playing. When his playing ended, his coaching and writing began. He then passed quickly from mortal to permanent, his name transferring to the aforementioned stand just six months after his death; the stand has since been succeeded by a statue. Nearly 150 years since the boy Giffen threw himself into bowling at W. G. Grace’s Englishmen as they practised there, then, the Oval continues to make his name and reputation a feature. Read Bernard’s book and you’ll find out why.

The Ashes of 1894–95

‘I SAY, OLD MAN . . .’ (1994)

‘I say, “Old Man”, who’s got those Ashes?’

The inquiry, in a contemporary cartoon by George Ashton, was polite but pointed. The off-field welcome was hospitable, the on-field intent explicitly hostile. England’s cricketers came to Australia holding an Ashes trophy some eleven years old, but it was in the 1894–95 series that their rivalry first showed its staying power.

In a new book on the series, Stoddy’s Mission (1994), David Frith has called it ‘the first Great Test Series’. It meets objective criteria. The rubber’s unfolding was perfect: England won the first two Tests. Australia the next two, and England the decider. These games featured passages so dramatic and captivating that even Queen Victoria asked to be kept abreast of scores. The patriotic pride involved in the result, moreover, reached a new intensity.

The British Empire was at a peak, and the country to which its Andrew Stoddart led his thirteen Englishmen was one recovering from the trauma of a banking crash while also experiencing the early rapture of proto-nationalism. Ethel Turner published her Seven Little Australians and Tom Roberts painted his ‘Golden Fleece’ in 1894. The Bulletin incorporated both ‘fair dinkum’ and ‘cobber’ into the local vernacular. Cricket presaged the incipient federalism. A gratuity left by Lord Sheffield, a patron of the previous English touring team, had been invested by the embryonic Australian Cricket Council in an intercolonial championship shield. Its first season, 1892–93, also saw Western Australia and Queensland join New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania as first-class cricket competitors. And Stoddart’s team was the first invited by colonies in cooperation rather than competition.

Stoddart himself was an eminent Corinthian, who had stayed behind after the 1887–88 tour of Australia to captain England at rugby and even play a few Australian rules fixtures. His troupe of five amateurs and eight professionals was one of the best assembled, including the destructive Surrey fast bowling duo of Tom Richardson and Bill Lockwood, two prodigious Yorkshiremen in batsmen John Brown and left-arm spinner Bobby Peel, plus the uncapped Lancastarian opening batsman Archie MacLaren. They resembled well-to-do holiday makers as they relaxed for the camera in Adelaide’s Botanical Gardens on arrival. But when his team was soundly defeated by South Australia in the first big match of the trip – with the inexhaustible thirty-five-year-old local hero George Giffen taking 11 wickets and top scoring in both innings – they knew they had their work cut out.

Perhaps it was ship-lag. It would be more than seventy years until an English team flew all the way to Australia. Stoddart’s men had boarded RMS Ophir, flagship of the Orient Line, at Tilbury on 21 September and not arrived in Adelaide until 2 November, MacLaren meeting his future wife en route. Such wanderlust was gradually outlining a global cricket. English teams had visited South Africa, India, North America by 1894; another would set off for the West Indies at the start of 1895. Since the pioneering visit of Australian aborigines, England itself had also received a great variety of touring teams, ranging from the Philadelphians to Indian Parsis.

The venue for the first Test for Stoddart’s team was the Sydney Cricket Ground which, with a century of development ahead of it, was a far cry from today’s arena. Plans had only just been laid for the Ladies Stand, and there was a lot of airspace for cricketers to play with: South Australian Joe Darling would hit a six there that carried 110 yards, through the location of the present M.A. Noble Stand, into the tennis courts outside. But, after years in which the venue had simply been the nebulous ‘Association Cricket Ground’, the flag ‘SCG’ was hoisted indicating its name change. Its pitch square had also been drastically improved by the introduction in August 1894 of Bulli soil.

No match in first-class cricket history had lasted as long as the First Test’s six days, produced as many as its 1514 runs, or involved so many twists. Australia recovered from three for 21 on the first day to make a Test record 586 in just seven hours and ten minutes, with Syd Gregory compiling the first Test double-century in Australia and joining in a record Australian ninth-wicket partnership that still stands.

England followed on after trailing by 261 runs and MacLaren was one of the few brave enough to stake four pounds on his team, when the odds against their win lengthened to 50/1. But rain fell on the fifth evening as Australia contemplated victory with eight wickets in hand and just 64 runs to get, and Stoddart sobered up the notoriously bibulous Peel beneath a cold shower so that he could exploit the uncovered surface. Australia’s 10-run defeat was mean reward for Giffen, who’d taken eight wickets from 118 overs and scored 202 runs, and not until 1981 at Headingley did a team win again after following on.

The First Test must have been agony for faraway English cricket followers. The cablegram service to London broke down at the end of the third day with the tourists on their knees, and those at home caught up with the match’s last three days in a single despatch that some would have suspected was a work of fiction. Mind you, watching the game and catching the score was difficult even in Australia. Although almost 600,000 attended the first-class season – in a country with a population of about 3.5 million – the smaller grounds meant that many spectators were turned away. The offices of the major newspapers where scores were posted regularly were thronged by thousands daily.

The Second Test at the MCG seemed almost as fanciful as the First. England lost MacLaren to the game’s first ball, were all out before lunch for 75, but still prevailed by 94 runs. The Third Test at Adelaide Oval was then marked by an all-round Test debut performance still unmatched: Australia’s Albert Trott made 110 runs without being dismissed and took eight for 43 as his team romped home by 362 runs. It was an ill-advised heresy when Stoddart became the first Test captain to insert his opponents in the Fourth Test: he lost in a day and a half on a rain-affected surface exploited by Giffen and Charlie Turner, in the process even throwing financial markets into confusion. When trade on the Ballarat Stock Exchange was interrupted by London-born brokers chorusing ‘Rule Britannia’, Australian colleagues responded by raising a Southern Cross and singing ‘The Men of Australia’. Communications between the Ballarat bourse and its Melbourne counterpart were limited one afternoon to a cable: ‘Nothing doing; cricket mad; Stoddart out’.

More than 100,000 attended a game for the first time as the Fifth Test was fought out at the MCG in an atmosphere tense from the moment of the toss. Australia’s captain Giffen wrote of the preliminaries: ‘He [Stoddart] was white as a sheet, and I have been told that the pallor of my own countenance matched his.’ Australia banked a robust 414, but MacLaren’s century ensured England’s virtual parity. Richardson’s tireless strivings on a blameless wicket gave England the edge and Brown saw his team home by seven wickets with what was then the fastest century in Ashes cricket in ninety-three minutes. Nobody in Test cricket has made it to 50 faster than his twenty-eight minutes.

Stoddart was a popular victor. Melbourne Punch versified: ‘Then spoke the Queen of England/Whose hand is blessed by God/I must do something handsome/For my dear victorious Stod/Let him return without delay/And shall dub him pat/A baronet that he may be/Sir Andrew Stoddart (Bat).’ But though its players had not recaptured the Ashes, the rubber did much to restore Australian self-confidence. The Argus opined: ‘A wise government desiring to improve our credit abroad may do worse than send away thousands of photographs of the scene on the MCG on Saturday. There appears to be an idea somewhere else that there is depression here. To the spectator on Saturday the word had no meaning.’ Three new loans were negotiated with London’s financiers during 1895.

Australian cricket had crossed a Rubicon. Giffen had become the country’s first great all-rounder – allegedly turning up in the children’s prayers (‘God bless Mummy, Daddy and George Giffen . . .’) – and his seasonal first-class double of 903 runs and 93 wickets has never been surpassed. The past was honoured: Syd Gregory was son of SCG groundsman Ned, veteran of the inaugural Test. The future was in the offing: 1894 also featured the birth of Victor Richardson, founder of the greatest of South Australian sporting dynasties, and Robert Menzies, longest-lasting and most cricket-fond of prime ministers. A tradition was emerging. Who had those Ashes? Nobody permanently.

Harry Trott

THE MADNESS OF KING HARRY (2004)

Cricketers great and humble meet one opponent equally. Sooner or later, all defer to time. Usually the end comes stealthily: muscles stiffen, reflexes slow, eyes dim. In some cases, though, it is abrupt, unceremonious, unkind; so sudden that it’s as though the individual was never there to begin with.

One hundred and five years ago, in the summer of 1897– 98, Harry Trott led Australia to its first win in a five-Test Ashes series. At thirty-one, he was in his athletic prime, and by common consent the world’s wisest cricket captain. On his watch had emerged what historian Bill Mandle has called ‘the unfilial yearning to thrash the mother country’, even as the constitutional undergirding of an Australian commonwealth was being erected. But at the peak of his fame, Harry Trott disappeared, never to play let alone captain another Test. And though he reappeared as a man, it was as a marginal figure, and a source of stifled embarrassment. For – didn’t you know? – poor Harry went mad.

Trott was born on 5 August 1866, third of eight children. Father Adolphus, an accountant, was scorer for the South Melbourne Cricket Club, whose batting and bowling averages eighteen-year-old Harry topped in his inaugural season. He was marked out from the first by uncommon temperament, batting with easy grace, giving his leg-breaks an optimistic loop. As befitted one destined to spend his whole working life in the Post Office as a postman and mail-sorter, he met everyone alike. On one occasion he was introduced to the Prince of Wales, who after a long and convivial conversation conferred on him a royal cigar. Later he was asked what he had done with it: the fashion was for preserving anything of royal provenance as a keepsake. Trott, though, simply looked puzzled. ‘I smoked it,’ he said.

In his equanimity, Trott was a rarity. Australian teams of the time were notoriously combustible, riven by intercolonial jealousies. Trott’s first skipper, Percy McDonnell, survived a ‘muffled mutiny’ against his leadership because of his over-reliance on New South Welshmen; his second, Jack Blackham, was weak, suggestible, and felt to be the cat’s paw of other Victorians; his third, George Giffen, asserted South Australian primacy simply by bowling himself interminably. Discipline was lamentable, with Australia’s 1893 tour of England especially unruly. ‘It was impossible to keep some of them straight,’ complained their manager. ‘One of them was altogether useless because of his drinking propensities . . . Some were in the habit of holding receptions in their rooms and would not go to bed until all hours.’

Appointed to lead Australia’s next trip to England in 1896, Harry Trott changed everything. He knew no favourites, was never quarrelsome, and above all showed a pioneering flair for tactics. At the time, rigid field settings and pre-determined bowling changes were standard; Trott set the trend of positioning fielders and employing bowlers with particular batsmen and match situations in mind, and rotating his attack to keep its members fresh. ‘His bowlers felt that he understood the gruelling nature of their work,’ said The Referee, ‘and that they had his sympathy in the grimmest of battles.’ To some, this sympathy seemed uncanny. Trott’s star bowler Hugh Trumble had days, he confessed, when his usual sting and snap were missing; Trott could sense such occasions within a few balls, and would whip him off. Sydney batsman Frank Iredale, meanwhile, was gifted but highly strung, a teetotaller. ‘Look here, Noss, what you need is a tonic,’ Trott counselled. ‘I’ll mix you one.’ Iredale made more centuries than any other batsman on tour, fortified by what Trott later admitted was brandy and soda.

In the end, the Australians were pipped 1–2 in the series, the defeats being narrow, their victory stirring. Opening the bowling on a whim at Manchester, Trott had W. G. Grace and Drewy Stoddart stumped in his first two overs: a decisive breakthrough. His leadership was then seen to even better advantage when England next visited Australia, and was overwhelmed 4–1. ‘It didn’t seem to matter to Mr Trott whom he put on,’ lamented Stoddart, ‘for each change ended in a wicket.’ Wisden thought him ‘incomparably the best captain the Australians have ever had’; the Anglo-Indian batting guru Ranjitsinhji concluded that he was ‘without a superior today anywhere’. The Melbourne Test of January 1898 not only drew many of the delegates from the marathon Constitutional Convention smoothing the path to Federation, it wholly distracted the public. As John Hirst says in Sentimental Nation (2000): ‘The Australian cricketers were better than the English. Who cared whether Australian judges were up to the mark?’ Victory could also be deemed a vindication of the cause. The Bulletin exulted: ‘This ruthless rout of English cricket will do – and has done – more to enhance the cause of Australian nationality than could be achieved by miles of erudite essays and impassioned appeal.’ Trott joined the Albert Park branch of the Australian Natives’ Association, and his double-fronted weatherboard in Phillipson Street became a place of pilgrimage. Trott’s employers, when some complained about the leave lavished on their most famous functionary, explained: ‘Harry Trott is a national institution.’