7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

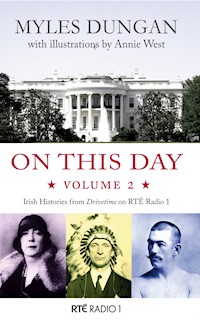

More fascinating, hilarious, and uncanny historical tales based on Myles Dungan's hugely popular Drivetime segment on RTÉ Radio One. The journey will take you through Ireland's historic influence at home and abroad: from the Irish architect of the White House to the Night of the Big Wind of 1839 (which just about levelled half the country). Find out how Wexford's Dollar Bay got its name (hint: it involves pirates) and how the Native American Choctaw Tribe came to the aid of the Irish during the famine. Uncover how a pair of ill-fitting boots may have made all the difference in the bloody Phoenix Park murders, and how the scientist Robert Boyle investigated the 'prolongation of life' and 'perpetual light'. With illustrations by Annie West, On This Day – Volume 2 is a whirlwind ride through Ireland's colourful – and often astonishing – history.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

On This Day

On This Day

Volume 2

Irish Histories fromDrivetime on RTÉ Radio 1

Myles Dungan

Illustrations by Annie West

ON THIS DAY – VOLUME 2

First published in 2017 by

New Island Books

16 Priory Hall Office Park

Stillorgan

County Dublin

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

Copyright © Myles Dungan, 2017

The Author asserts his moral rights in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

Print ISBN: 978-1-84840-636-0

Epub ISBN: 978-1-84840-637-7

Mobi ISBN: 978-1-84840-638-4

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owner.

British Library Cataloguing Data.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

New Island Books is a member of Publishing Ireland.

Cover images: The White House South Lawn © Mark Skrobola; John Lawrence Sullivan © Joe Maria Mora; Éamon de Valera in Indian headdress, 18 October 1919 (Reproduced by kind permission of UCD-OFM Partnership); Nora Joyce, courtesy of Alamy; RMS Titanic © FGO Stuart.

To Dr Eileen Butler, Dr Deirdre Lynch and Mr Barry McGuire, without whom … !

Acknowledgements

My profound thanks are due to the estimable and indispensable Tom Donnelly, producer of the RTÉ Radio One Drivetime programme, for keeping faith with this relentlessly non-topical Friday column. Thanks also to my affable and accomplished RTÉ History Show producer Alan Torney for his indulgence in allowing me to record much of the material for broadcast on his dollar. John Davis, now retired, again played a huge part in improving the items and making them something more than a mere four-minute spoken dirge.

I am, as before, grateful to Edwin Higel and Dan Bolger of New Island Books for taking this project on in the first place and, despite the wisdom of hindsight, for agreeing to follow up with two more years of anniversary etchings. Thanks to them also for persuading the redoubtable Annie West to shelve whatever useful project she was working on at the time and get involved in illustrating twelve of the stories in this and the previous volume. To Shauna Daly, thank you for saving me from myself. And to all those who had the good sense and generosity to be born, die or do something noteworthy on a Friday, I am eternally in your debt.

And finally, to the ever accommodating and supportive Nerys Williams and to the ever sceptical Amber, Rory, Lara, Ross and Gwyneth, thank you all for the grounding – and here we go yet again.

Foreword

And so, once more with feeling. Or encore une fois, as the French would say. Or should that be ‘encore un fois’? I could never hack that masculine/feminine thing in French.

‘On This Day’ has now survived for an entire American presidential term. Especially if William Henry Harrison is the president in question. The poor man died after only one month in office, helped to the pearly gates by giving a two-hour inauguration address, hatless and coatless, on a cold and wet March day in Washington, D.C. It is sobering to think that his inauguration speech was the equivalent of about six months of ‘On This Day’. But enough about William Henry Harrison.

As I mentioned in the distinguished preceding volume, the idea for ‘On This Day’ was stolen from the 1980s. It was already a tried and tested broadcasting format, allowed to pass on, before being triumphantly resurrected. It will inevitably lapse as a successful column in a few years, only to be picked up by some other concept thief in 2035. And so on. One wonders whether, a century from now, when tour operators are running sun holidays to Antarctica, it will re-emerge triumphantly. What will the slick, plausible ‘On This Day’ presenter of 2116 make of the events of 2016? Will listeners to Drivetime on 23 June 2116 shudder to hear that an obscure monarchy called the United Kingdom (now four distinct political entities), voted for political and economic self-immolation, one hundred years ago, on this day. And what about 8 November 2116? How will it be fondly remembered? The event that ultimately led to the secession of over half the states of the Union – the election of Donald Trump as forty-fifth and final President of the United States of America – took place one hundred years ago, on this day.

Not to worry, though. Columns like this will most likely be redundant in a world where only tropical aquatic creatures still survive. Is this unseemly pessimism? I’m sure it is. And if not, I warrant the sharks and ghost shrimp won’t carp.

So, what’s new this time around?

In On This Day – Volume 2, you can thrill to the horrors of the ‘Night of the Big Wind’ and the Invincibles, gasp at the genius of novelists Laurence Sterne and Arthur Conan Doyle, hiss at the iniquity of the informer Francis Magan, the Norman warlord Strongbow, and ‘Half-hanged’ McNaughton, and sob at the fate of the hapless RMS Titanic, the fearless Rollo Gillespie, and the luckless Kevin Barry. And you can, once again, enjoy Annie West’s idiosyncratic take on some of the narratives included in this volume.

In fact, if you have had the good sense to purchase this collection in November, you will be in a position to savour, in advance of broadcast, more than half a dozen columns. This will enable you, should you engineer a communal audience for Drivetime in December, to astonish all your friends with your intimate knowledge of Irish history. You will also be able to correct some of the more egregious errors before they are broadcast. This is the literary equivalent of the practice in horse racing of ‘past-posting’. However, be wary of how you use this dizzying power, as you may find yourself in the vicinity of an even greater pedant, with his or her own copy of On This Day – Volume 2 in hand.

Apologies for the prosaic nature of the title, by the way. Some of the more colourful suggestions were rejected, such as On This Day – The Golden Years, On This Day – Go Set a Watchman, and On This Day – Dead Man’s Chest.

As always, any errors are attributable to the mistakes, exaggerations and downright lies of the biographers and historians from whom the information contained in these columns has been culled. The author, himself an innocent victim of such fraud, #fakenews, special pleading or laxity, is entirely blameless.

Two years ago, in the foreword to the preceding volume, I asserted confidently that ‘I certainly have made nothing up’. Unfortunately, I must confess that is not the case here. One column is entirely fictional. The fact that 1 April 2016 fell on a Friday was just too tempting to resist.

Someday I am sure I will run out of interesting stories. But we’re not there yet.

Myles DunganApril 2017

January

29 January 1768

Oliver Goldsmith’s first play, The Good-Natured Man, opens in London

Oliver Goldsmith must have been the despair of his mother – his father didn’t live long enough to see him fail at almost everything to which he turned his hand. Eventually he would write one of the finest plays, one of the best novels, and one of the most ambitious long poems of the eighteenth century, but not before he had managed to destroy almost every opportunity that came his way.

Goldsmith was born the son of a Church of Ireland curate, either in Longford or Roscommon, in November 1728. In 1730 the family moved to Westmeath when his father was appointed rector to a parish in that county. In 1744 Goldsmith was admitted to Trinity College. There he learned to drink, gamble and play the flute. Although neither he nor the college greatly profited from his brief tenure, his subsequent fame has earned him one of the two most prominent statues in that venerable institution, overlooking College Green.

His father died around the time he graduated, and Goldsmith moved back into the family home so that he could be a burden on his poor mother, rather than on himself. He obtained a position as a tutor, and quickly lost it after a quarrel. After this, he decided to emigrate to America, but managed to miss his boat. He then took fifty pounds with him to Dublin, to help establish himself as a student of law, but he lost it all at gambling. He pretended to study medicine in Edinburgh, but rather than knuckle down he took off on a grand tour of Europe, keeping body and soul together by busking with his flute.

Eventually he settled in London and began to churn out hack writing to keep him gambling in the manner to which he had become accustomed. Due to the fact that he, in spite of himself, also occasionally published something of merit, he came to the attention of the famous wit and lexicographer, Samuel Johnson. He became a founder member of the club of writers and intellectuals unimaginatively entitled ‘The Club’, which included Johnson, his biographer James Boswell, the actor-manager David Garrick, the statesman and philosopher Edmund Burke, and the painter Joshua Reynolds. Heady company for a young ne’er do well from Ballymahon.

In 1760 he wrote the epic poem, The Deserted Village, elements of which schoolchildren of a certain age were forced to learn by heart. The poem tells the story of the fictional village of Auburn, laid to waste in order to make way for the ornamental gardens of a local landowner.

… the man of wealth and pride

Takes up a space that many poor supplied;

Space for his lake, his park’s extended bounds,

Space for his horses, equipage, and hounds:

The robe that wraps his limbs in silken sloth

Has robbed the neighbouring fields of half their growth.

He followed this poem with his charming novel, The Vicar of Wakefield, in 1766, and one of the greatest comic plays in the English language, She Stoops to Conquer in 1773. Prior to the play, he had a modicum of success with The Good-Natured Man, which bombed on the London stage but managed to sell a large number of copies when the text was published.

Success enabled Goldsmith to carry on with a lifestyle that virtually guaranteed an early exit. And so it proved. He continued to gamble and drink on a spectacular scale, and ended up in debt and in bad health. He died in 1774 at the age of forty-five.

Despite all his achievements as a novelist, playwright and poet, he is probably best remembered today for his Elegy on the Death of a Mad Dog, an inspired piece of doggerel (no pun intended). The title gives away the ending, but the short verse is a satire on hypocrisy and corruption in which a man of acknowledged standing, guilty of these vices, is bitten by a dog and left for dead by the commentariat. Then comes the sting in the tail (and yes, the pun is intended this time).

But soon a wonder came to light,

That showed the rogues they lied:

The man recovered of the bite,

The dog it was that died.

Oliver Goldsmith’s play, The Good-Natured Man, opened in London to less-than-ecstatic reviews, two hundred and forty-eight years ago, on this day.

Broadcast 29 January 2016

15 January 1825

The suicide of banker Thomas Newcomen

If you thought Irish banking failures and inquiries were peculiar only to the twenty-first century, then think again. As Woody Guthrie pithily put it:

Some men rob you with a gun

And some with a fountain pen.

The Irish banker has been ruining himself and his customers, as well as cleverly masking his losses, since the early 1800s.

Let us look at some of the most spectacular Irish banking collapses of the nineteenth century. Most of them involve politicians as well as bankers. Strange that.

To begin, there was the scandal of the Tipperary Joint Stock Bank. It was run by the Irish Liberal MP for Carlow, John Sadlier, and his brother James, MP for Tipperary. When the bank ran out of money in 1856, John Sadlier committed suicide on Hampstead Heath, leaving James to face the music. This he did for a while, before he absconded. He ended his days in Switzerland, the natural home of the dodgy banker. Investigations revealed that the collapse of the bank was due to John Sadlier’s embezzlement of funds on an outrageous scale. Before he shuffled off his mortal coil, he’d stolen nearly £300,000 from the vaults. The whole episode is said to have provided Charles Dickens with the inspiration to create the dubious financier, Mr Merdle, in Little Dorritt, published in 1857.

Fast forward to 1869, and to an egregious example of Ireland’s capacity to forgive a scoundrel, another MP, Joseph Neale McKenna, Chairman and Managing Director of the National Bank of Ireland in the 1850s and 60s. He somehow managed to combine in one person the roles later held by Sean Fitzpatrick and David Drumm of Anglo Irish Bank. Either Seanie and David were total slackers or McKenna was an absolute hive of fiduciary energy.

McKenna successfully ran the bank into the ground due to a number of unwise investments in pursuit of growth and greater market share. Aren’t we fortunate that our bankers shrugged off that bad habit a century and a half later? By the time he was forced out in 1869, accused of cronyism and being far too generous with his own paycheque – other habits utterly alien to the modern equivalent – the National Bank of Ireland had debts of almost £400,000. The bank did manage to survive, however, and McKenna, MP for Youghal, lost his seat, but later re-invented himself as a Parnellite and was re-elected in South Monaghan. This proves the theory that if Charles Stewart Parnell had nominated a pile of pigeon droppings for a nationalist constituency, they would have won the seat with a thumping majority.

Another flawed banker, however, was not so lucky where the Uncrowned King of Ireland was concerned. William Shaw briefly held the leadership of the Home Rule Party after Isaac Butt died in 1879 until, in 1880, he got the bum’s rush when Parnell stood against him. Interestingly, Shaw was supported in the leadership contest by one James McNeale McKenna. These banker/politicians do seem to stick together. Shaw was also founder and Chairman of the Munster Bank. In 1885 he resigned, having received loans to the value of £80,000 – twice the amount of the rest of the directors combined. Again, we are fortunate that this practice was completely stamped out before the twenty-first century. The Munster Bank did not outlive his chairmanship for long. It went bust the following year.

Finally, we go quickly to the 1820s, and Thomas Newcomen, a Viscount and, surprise surprise, a politician. He inherited the Newcomen Bank, voted for the Act of Union in 1800, spent much of his time in the bank’s fine new headquarters – now the Rates Office beside Dublin Castle – and proceeded to drive the family business into the ground, taking many depositors with him. Newcomen was described as a reclusive, Scrooge-like figure who enjoyed gloating over the precious metals left in his safe keeping.

Thomas Newcomen, driven to distraction by the collapse of his family bank, took his own life, one hundred and ninety-one years ago, on this day.

Broadcast 15 January 2016

6 January 1839

The night of ‘The Big Wind’

Snow fell over much of the country on 5 January 1839, but then, as often happens in Ireland, the weather changed completely. Temperatures rose, and the snow rapidly melted. For a few hours, the country basked in unseasonable warmth. No one had the slightest idea what lay in store.

Gradually, during the day of the 6 January, the winds rose. The first area affected was Co. Mayo, where a strong breeze and heavy rains swept in from the Atlantic at around midday. Nollaig na mBan, the religious feast of the Epiphany, wasn’t going to be that pleasant a day after all.

There was a belief among the impressionable that the world would come to an end, that the Apocalypse would descend on 6 January and that one Nollaig na mBan would finally prove to be the day of Final Judgement. And that was before the Apocalypse of the Night of the Big Wind.

The squalls that first appeared on the west coast quickly moved eastwards, and worse weather followed in its wake. The storm began to gather strength, and soon it was powerful enough to blow down the steeple of the Anglican church in Castlebar. As it moved across the midlands, the wind gusted at over one hundred knots – roughly one hundred and eighty-five kilometres an hour. According to the scale devised in 1805 by the Navan-born hydrographer and naval officer Sir Francis Beaufort, that was a force twelve, or hurricane force.

It was the most destructive wind to hit Europe in more than a century – another damaging, continent-wide hurricane in 1703 had largely bypassed Ireland. But our geographical position on the western periphery of the continent meant that this time early Victorian Ireland bore the brunt of nature’s awe-inspiring strength. By the time the wind had blown itself out, upwards of three hundred people were dead; many had died at sea. Forty-two ships had sunk. Most of the shipping damage was on the badly hit west coast. So strong were the surging winds that some inland flooding was caused by seawater.

The Big Wind spared no one. Well-built aristocratic homes and military barracks were destroyed or badly damaged, as were the bothies and cottages of the rural poor. Exposed livestock were vulnerable, not only to the Big Wind itself, but to the aftermath, as crops and stores of fodder were obliterated.

Ironically, given the prevailing conditions, much of the damage was caused by fire. The winds fanned the embers of turf fires abandoned overnight in hearths. The sparks set fire to thatched roofs. These conflagrations were then spread to adjacent roofs, especially in small towns like Naas, Kilbeggan, Slane and Kells. Seventy-one houses were burned in Loughrea, and over one hundred in Athlone.

County Meath was right in the path of the wind. The Dublin Evening Post reported that:

The damage done in this county is very great. Not a single demesne escaped, and tens of thousands of trees have been snapped in twain or torn up by the roots, and farming produce to an immense amount destroyed.

The city of Dublin did not escape either. The tremendous gusts devoured a quarter of the buildings in the capital as the wind raced across the Irish Sea to Britain and continental Europe before finally dissipating. The River Liffey rose and flooded the quays in the centre of the city. A noon service at the Bethesda Chapel in Dorset Street had given thanks, on 6 January, for deliverance from a potentially destructive fire – that night the wind whipped up the embers of the fire and consumed the church.

One of the unexpected consequences of the Night of the Big Wind came almost seventy years later, when the British Government introduced an old-age pension for the over-seventies. As the formal registration of births in Ireland had only begun in 1863, many septuagenarians were entitled to a pension, but had no birth certificates to prove their age. One of the methods used to ascertain their age was devised by civil servants, who would ask the question ‘Do you remember the Night of the Big Wind?’ If they did remember it, they got their pension, as they were deemed old enough to qualify.

Hurricane-force winds destroyed property and killed hundreds of people and animals when ‘The Night of the Big Wind’ struck Ireland, one hundred and seventy-eight years ago, on this day.

Broadcast 6 January 2017

8 January 1871

The birth of Sir James Craig

The most familiar photograph of James Craig is of a rather startled but steely-eyed elderly man with rapidly receding hair and a prominently thick, grey moustache. He looks like someone you wouldn’t want to trifle with. In this instance, looks were not deceptive.

Craig was born in Belfast in 1871, the son of a distiller. He was a millionaire by the age of forty, with much of his money coming from his adventures in stockbroking. This meant that he had plenty of resources to devote to his favourite pastime, keeping Ulster in the Union. This he was very good at indeed.

As did many a younger son of a well-established family, he first distinguished himself in the army. Everybody had enjoyed the first Boer War so much that they decided to do it all over again. So, from 1899, Craig served as an officer in the Third Royal Irish Rifles. He was, at one point, imprisoned by the Boers, and was finally forced home due to dysentery in 1901.

His name is, of course, as indelibly associated with that of Edward Carson as is Butch Cassidy’s with that of the Sundance Kid. Craig came into his own in 1912 in the organisation of unionist opposition to the prospect of Irish Home Rule. He was central to the creation of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and the promulgation of the Ulster Solemn League and Covenant, in which Ulster said ‘no’ with an emphatic flourish. While Carson made the speeches and was the most public opponent of Irish devolution, Craig was seen as the organisational genius who developed the muscular element to back up Carson’s rhetoric. Craig was, for example, one of the men behind the Larne gun running of 1914, which brought 20,000 rifles to the UVF.

Unlike Carson, Craig was perfectly content with the exclusion of the six counties from the ambit of Home Rule. The Government of Ireland Act of 1920 gave Ulster, somewhat ironically, a Home Rule parliament of its own. In February 1921, Craig succeeded Carson as leader of the Ulster Unionist party. Later that year he fought the 1921 election, while asking unionist supporters to ‘Rally round me that I may shatter our enemies and their hopes of a republic flag. The Union Jack must sweep the polls. Vote early, work late.’ If you were expecting ‘vote often’ there … well, that wasn’t Craig’s style. In June 1921 he became the first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland.

His most famous speech was made in the Northern Ireland Parliament in 1934 and, we are told, is often misquoted. He did not actually refer to that assembly as a ‘Protestant parliament for a Protestant people’. What he did say was, ‘my whole object [is] in carrying on a Protestant Government for a Protestant people.’ You might well be forgiven for wondering what the difference is.

He also reflected, on one occasion in the Northern Ireland House of Commons, that:

It would be rather interesting for historians of the future to compare a Catholic State launched in the South, with a Protestant State launched in the North, and to see which gets on the better, and prospers the more. It is most interesting for me at the moment to watch how they are progressing. I am doing my best always to top the bill, and to be ahead of the South.

Arguably, he achieved that ambition during his tenure as Prime Minister, though large-scale fiscal transfers from London, as well as the Anglo-Irish Economic War of the 1930s, undoubtedly helped the Northern Irish economy to keep its nose ahead of the under-performing Irish Free State.

Craig was almost obsessive in his desire to have Northern Ireland treated as an integral part of the United Kingdom, to such an extent that he occasionally acted contrary to the apparent interests of its population. This can be seen clearly in his insistence, in 1940, that conscription be introduced in Northern Ireland when World War II broke out. Winston Churchill wisely passed on that particular poisoned chalice, fearing the inevitable backlash from the sizeable nationalist population and the reaction in the Irish Free State.

Towards the end of his days, Craig began to take on an uncanny physical resemblance to the man who, in later life, would become the Rev. Ian Paisley. When Craig died in November 1940, aged sixty-nine, he was still Northern Ireland Prime Minister.

Captain James Craig, later First Viscount Craigavon, was born one hundred and forty-five years ago, on this day.

Broadcast 8 January 2016

22 January 1879

James Shields is elected Senator for Missouri

James Shields from Co. Tyrone was an extraordinary Irishman, though his name is virtually unknown in his native country. He had an uncle of the same name who emigrated to the US and became a senator for Ohio. Not to be outdone, James Shields Jr left Ireland at the age of twenty, and went on to represent not one but three states in the US Senate. A unique achievement, unlikely ever to be repeated.

In 1849 he served one term as a US senator for the state of Illinois… His election was helped by what came to be known as the ‘lucky Mexican bullet’. This had struck him while he was a brigadier general in the Mexican-American war in 1846, and he used it for all it was worth in his campaign. His opponent for the Illinois seat was the incumbent Sydney Breese, a fellow Democrat. A political rival wrote of Shields’s injury:

What a wonderful shot that was! The bullet went clean through Shields without hurting him, or even leaving a scar, and killed Breese a thousand miles away.

Shields is also unusual in that he replaced himself in the Senate. When he was first elected in 1849 it emerged that he had not been a citizen of the US for the required nine years. He had only been naturalized in October 1840, leaving him a few weeks short, so his election was declared null and void. However, he would be entitled to take his seat after a special election was immediately called to replace him as he had by then been naturalized for the required period. He stood again, and won the seat for a second time.

When he failed in his bid to be re-elected six years later, in 1855, he moved to what was then the Minnesota ‘territory’, from where he was returned in 1858 as one of the new State’s first two senators, after Minnesota achieved statehood. Later, during the Civil War, he distinguished himself as a union general and then settled in Missouri.

He had obviously taken a liking to the Senate chamber, because in 1879 he contrived to get re-elected to that house, from Missouri, at the age of seventy-three. He died shortly after taking office.

But Shields is possibly even more important for something he didn’t do.

In 1842 he was already well known in his adopted home of Illinois. He was a lawyer, and was serving in the State Legislature as a Democrat. After one of those periodic economic recessions hit the nation in the 1840s, Shields, as State auditor, issued instructions that paper money should no longer be taken as payment for State taxes. Only gold or silver would be acceptable. A prominent member of the Whig party, one Abraham Lincoln, took exception to the rule, and wrote an anonymous satirical letter to a local Springfield, Illinois newspaper, in which he called Shields a fool, a liar and a dunce. This was then followed up by Lincoln’s wife-to-be, Mary Todd, with an equally scathing letter of her own. When Shields contacted the editor of the newspaper to find out who had written the second letter, Lincoln himself took full responsibility. A belligerent Shields, accordingly, challenged the future US president to a duel. The venue was to be the infamous Bloody Island in the middle of the Mississippi river, dueling being illegal in Illinois.

Lincoln, having been challenged, was allowed to choose the weapons and set the rules. He did this to his own considerable advantage, opting for broadswords as opposed to pistols. While Shields was a crack shot, he was only five feet nine inches in height, as opposed to Lincoln’s towering six feet four inches. When the rivals finally met on 22 September 1842, Lincoln quickly demonstrated his huge reach advantage by ostentatiously lopping off a branch above the Irishman’s head with his weapon of choice.

When the seconds ticked by and other interested parties intervened, peace was negotiated between the two men, though it took some time to placate the pugnacious Shields and persuade him to shake hands with Lincoln.

The man who might have abruptly ended the life and career of Abraham Lincoln, and subsequently change the course of American history, James Shields from Co. Tyrone, was elected as Senator for Missouri, one hundred and thirty-seven years ago, on this day.

Broadcast 22 January 2016

13 January 1880

The Irish film director, Herbert Brenon, is born

They weren’t presented with anywhere near the same sort of pizzazz or pomp first time around as they are now, but the 1927 and 1928 Academy Awards – the first of their kind, at a time before they became known as ‘the Oscars’ – were still hugely important to the burgeoning Hollywood community of film-makers.

At the private dinner for the nominees at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel in Los Angeles, there was a significant Irish presence. The dinner was hosted by the president of the relatively newly formed Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Douglas Fairbanks, on 16 May 1929. It cost five dollars to get in, there were almost three hundred invited guests, a dozen categories, with two to four nominees in each category. The entire ceremony lasted fifteen minutes – about the length of Billy Crystal’s opening monologue these days. It remains the only Academy Award ceremony not to have been broadcast on radio or TV.

But who was the Irish-born nominee that night? It wasn’t the celebrated Dubliner Rex Ingram, whose brilliant career was coming to an end. Neither was it the Dublin-born art director Cedric Gibbons, though he did design the winner’s statuettes, which, at the time, were yet to be iconic. The Irish nominee, in the Best Director category, was another Dubliner, Herbert Brenon, director of over three hundred movies, in a career that dated back to the migration of the film industry to the west coast, and to its new home in the Hollywood Hills in Los Angeles.

Brenon was born in Dublin in 1880, son of an English father – who was a drama critic – and an Irish mother, Frances, who was a writer. He had emigrated to the USA at the age of sixteen and began performing on the vaudeville stage almost immediately. In the early 1900s, with vaudeville beginning to provide slim pickings, he joined Carl Laemmle’s Independent Motion Picture Company as a screen writer, working with glamorous stars like Florence Lawrence and Mary Pickford.

He directed his first film in 1912, and was quickly ranked alongside some of the Hollywood greats of the silent era, like Cecil B. de Mille, D.W. Griffiths, and his own compatriot, Rex Ingram. While some of his output was frivolous, much of what he created dealt with difficult and challenging subjects, like the fall of the Romanov dynasty, and life in a Jewish ghetto. His only obvious genuflection to his country of origin was Kathleen Mavourneen, made in 1913.

He worked with some of the biggest names of the silent era: Theda Bara, Ronald Colman, Lon Chaney, Clara Bow and Pola Negri. He also had an adventurous career. While making the film Neptune’s Daughter (1949), he was badly injured when a tank exploded. Later, while making a film on location in Italy, he was kidnapped by bandits.

In 1926 Brenon became the first director to try his hand at adapting F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925) for the screen. Not an easy thing to do convincingly, with no dialogue available during the silent movie era. Brenon’s version was produced by the legendary Adolph Zukor and Jesse Lasky, and released by Paramount.

Two years before, the same team had produced and directed the first full-length film adaptation of J. M. Barrie’s classic children’s story Peter Pan (1911). Brenon was also first to direct the film version of Beau Geste (1924), the French Foreign Legion novel by P. C.Wren.

On the night of 16 May 1929, he waited – not for too long given the length of the ceremony – to find out whether he had won the first Best Director Academy Award for a film called Sorrell and Son (1927). He hadn’t. The gold-plated gong went instead to Frank Borzage for Seventh Heaven (1927).

Like a lot of his contemporaries, Brenon wrote off the ‘talkies’ as a passing fad. His illustrious career did not prosper when Hollywood adopted sound, and his career ended with a number of undistinguished movies made in England. He made his last film in 1940 and died in Los Angeles in 1958.

Alexander Herbert Reginald St. John Brenon, to give him his full name, was born in Dublin, one hundred and thirty-seven years ago, on this day.

Broadcast 13 January 2017

27 January 1885

Charles Stewart Parnell turns the first sod for the West Clare Railway

In extenuation for his many crimes, it was once suggested that at least Benito Mussolini, the Italian Fascist leader, ‘made the trains run on time’. It is hardly enough, however, to erase the invasion of Abyssinia, his alliance with Nazi Germany, nor the liquidation of a number of inconvenient political opponents from our minds.

But you can’t offer that excuse in the case of one of the great villains of Irish history, Captain William Henry O’Shea. The reason O’Shea didn’t make the trains run on time was because he was one of the great parliamentary champions of the notoriously dilatory West Clare Railway. This narrow-gauge iron road ran, if that particular word doesn’t suggest too much urgency, between Ennis and Moyasta, and thence west to Kilrush, or east to Kilkee, whichever was your preference. It travelled the route via Ennistymon, Lahinch and Milltown Malbay. It was the last operating narrow-gauge passenger railway in the country. The problem was that it just wasn’t very reliable.

Only twenty-seven miles long when it opened in 1887, it was actually two railways, the West Clare and the South Clare, that met at Milltown Malbay. Hardly comparable to the iconic junction of America’s Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads at Promontory Point in Utah, but very exciting nonetheless for the good citizens of Clare, who now found it much easier to travel around and connect with the country’s main rail network at Ennis. The line was later extended to forty-eight miles in overall length.

Although work had already started the previous November, the sod was not officially turned on the original construction site until January 1885. O’Shea, the semi-detached Nationalist MP for Clare, wanted his pound of flesh after months of lobbying Parliament to ensure that funds were made available for the project, so the party leader himself, Charles Stewart Parnell, was recruited to pop over from his unwedded bliss with O’Shea’s wife Katharine in London, and do the needful with a shovel. Also in attendance was the man chosen to build the railway, one William Martin Murphy, who would have his own days in the sun during the infamous Dublin Lockout of 1913.

Of course, the railway was immortalized by its hilarious brush with the songwriter and performer Percy French. He successfully sued the line for loss of earnings after arriving four and a half hours late for an engagement in Kilkee on 10 August 1896, thanks, he alleged, to the rather relaxed attitude of the railroad employees towards the joys of timetabling. He won £10 and costs at the Ennis Quarter Sessions in January 1897.

Now, most sensible corporations, when in a hole, stop digging. But not the West Clare Railway. They appealed the decision at the next Clare Spring Assizes, held before the formidable jurist, Chief Baron Palles. French might have forfeited the case, as he arrived an hour late for the hearing. But his explanation that he ‘took the West Clare Railway here, Your Honour’, probably sealed the case in his favour.

In the course of his contribution, French offered a couplet that suggested he had a certain composition in mind already. He informed the Chief Baron that, ‘If you want to get to Kilkee/ You must go there by the sea’. The lines didn’t actually make it into his final revenge on the hapless railway line: ‘Are Ye Right There Michael’, which begins:

You may talk of Columbus’s sailing

Across the Atlantical Sea

But he never tried to go railing

From Ennis, as far as Kilkee

Incidentally, on the same day as Percy French’s court appearance, one Mary Anne Butler from Limerick was also suing the railway, alleging that she had been attacked by a malevolent donkey on the platform in Ennis.

The line eventually closed down in 1961, but thanks to a group of local enthusiasts, the West Clare Railway lives once more. Part of the line, between Moyasta and Kilkee, has been restored, and one of the original engines, the exquisite Slieve Callan, is back in use.