Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

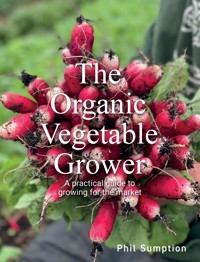

The Organic Vegetable Grower is a practical guide for those growing, or wishing to grow, market and sell organic vegetables for a living. The book is rooted in organic principles and covers: •tGetting on the land – gaining the skills and setting up •tHow to maximise diversity and productivity at a range of scales •tA crop-by-crop guide to the basics of growing quality produce •tSelling and marketing your produce •tThe human element - managing staff, complexity, and avoiding burnout Lavishly illustrated with over 250 colour photographs, The Organic Vegetable Grower highlights best practice within the industry with numerous case study examples. It focuses on agroecological and regenerative approaches that build soil health and biodiversity to grow quality vegetables for a growing market. Packed with the latest research, innovations, and grower knowledge, it will also be invaluable for advisers and students of organic farming.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 403

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Roger Hitchings

Chapter One Principles and Approaches

Chapter Two It’s All About the System

Chapter Three Getting on the Land

Chapter Four Setting Up

Chapter Five Soil Health

Chapter Six Rotations and Crop Planning

Chapter Seven Seeds and Plant-Raising

Chapter Eight Living with Weeds

Chapter Nine Managing Pests and Diseases Agroecologically

Chapter Ten Protected Cropping

Chapter Eleven Harvesting, Storage, Selling and Marketing

Chapter Twelve Managing Labour, Time and Complexity

Chapter Thirteen Crop by Crop Guide

Chapter Fourteen Economic and Environmental Sustainability

Sources of Information

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

Firstly, thanks to Jason Horner for alerting me that Organic Vegetable Production: A Complete Guide had gone out of print. Secondly, thanks to Gareth Davies and Margi Lennartsson for giving the green light for me to write a completely new version of this old classic, and to Crowood for enabling it to happen.

The biggest thanks go to my partner, Isabeau Meyer-Graft, for help with proofreading, support and much more. Also, to Roger Hitchings, for many helpful comments and suggestions, and agreeing to write the Foreword. I am also grateful to Jim Aplin, Nathan Richards, Kate Collyns, Pete Richardson, Tony Little, Antonia Ineson, Kate McEvoy, Mark Measures, Pete Dollimore, Iain Tolhurst, Tamara Schiopu, Suzy Russell and Dom van Marsh for assistance with aspects of the text along the way.

Photographic Acknowledgements

Brian Adair: 103 (all)

Jayne Arnold: 86–87, 157 (bottom left and right)

Mandy Barber: 217 (both)

Adam Beer, Pitney Farm Market Garden: 15 (top right), 48 (left), 49 (bottom) right), 50 (top left), 50 (bottom) left), 90, 93 (all), 100 (right), 108 (left), 120 (top right and (bottom) left), 152, 206, 212, 222

Pam Bowers: 27 (bottom), 47 (bottom), 70, 115, 120 (top left), 162 (top left), 162 (top right), 162 (bottom) right), 163 (right), 173, 196, 13.32

CAWR: 116 (all)

Kate Collyns: 27 (inset), 72

Culinaris Saatgut: 215

Tim Dickens: 11 (right), 12 (right), 14 (top left), 15 (top left), 34 (left), 35, 153 (bottom) left), 162 (bottom) left), 178 (bottom), 179, 181

Pete Dollimore: 145, 150 (both), 157 (top right)

Ecological Land Cooperative: 39 (top)

FarmStart: 38

David Frost: 184

Groundswell: 16

Ed Hamer: 28

Chris Holton: 27 (top)

Jason Horner: 26, 121 (top)

Scott Hunter: 23

Antonia Ineson: 56 (left)

Paul Izod: 106

Debbie James: 110

Holly Jarvis: 39 (bottom)

Stephan Junge: 135 (both)

Landgilde and Wageningen University & Research: 41 (top)

Henryk Luka, 130

Marley of Bennison Farm: 40, 96, 132, 153 (bottom) right), 162 (middle left), 179 (both), 178 (top), 185, 211

Organic Research Centre: 13 (top left), 14 (top right), 17, 29 (left), 58 (right), 65 (both), 66, 75 (bottom), 76 (left), 82 (left)

Adam Payne: 41 (bottom), 46, 47 (top), 50 (middle left), 75 (top), 100 (left), 120 (top middle), 159, 161 (bottom) left), 186, 188, 190, 193, 195, 201

Morten Pederson: 14 (bottom) left), 24 (bottom)

Morten Pedersen/Trill Farm Garden: 94

permacultureprinciples.com: 20

Pitney Farm Market Garden: 21, 98, 153 (middle right), 165 (top right), 177

Ben Raskin: 109

Nathan Richards: 11 (left), 14 (bottom) right), 50 (top right), 71 (left), 105 (right), 167 (top right), 170 (right), 202, 207

Pete Richardson: 37, 71 (right), 166 (top left)

Patricia Schwitter/FiBL: 155 (top)

David Shaw, Raindrops: 133 (bottom)

Jonathan Smith: 166 (bottom) left)

Claire Stapley: 32

Hans Steenbergen: 205

Emma Treanor, Sandy Lane Farm: 9, 25, 57, 133 (bottom) (potatoes), 161 (top left), 161 (bottom right), 162 (middle right) 170 (left), 182, 191, 203 (top), 214

Paul van Midden: 148, 153 (top left)

Anja Vieweger/Organic Research Centre: 157 (top left)

Chloe Ward: 84

Ashley Wheeler: 24 (top), 34 (right), 73, 82 (right), 108 (right), 145, 146 (bottom), 153 (top right), 164, 165 (middle right and (bottom) right), 167 (bottom) right), 183, 187, 189, 197, 199, 200, 203 (bottom), 210

Adam York: 48 (right), 124, 129 (right), 166 (top right), 220

Foreword

Much has changed since the publication by Crowood of Organic Vegetable Production: A Complete Guide in 2005 and yet some things have stayed more or less the same. Notable changes include a greater focus on seed and food sovereignty, a much greater awareness of the realities of climate change, financial ups and downs and, more latterly, the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine. All of these have affected organic food production and not always in a good way.

The amount of support for organic horticulture has increased. The Organic Growers Association was reborn as the Organic Growers Alliance (OGA) in 2007 and transitioned into a Community Interest Company (CIC) in 2019. It continues to provide support, representation and an increasing body of invaluable information for organic growers. Organisations such as the Soil Association and Garden Organic continue to provide valuable information and support, while the Landworkers’ Alliance (LWA) campaigns to improve the livelihoods of all land-based workers, including growers.

The marketplace continues to be dominated by supermarket sales, but there is a much greater diversity of marketing initiatives at local and regional levels. Whichever part of the market you are supplying, or seeking to supply, there are challenges and these are increasing, not least because of the increasing variability and unpredictability of UK weather. Other factors to consider when working out marketing plans include addressing the increasing interest in veganism and tapping into interest in ‘heritage’ varieties and unusual vegetables.

A welcome, if belated, change is a significant increase in awareness of the importance of soil health and the fundamental importance of soils, both in terms of food production and as repositories of sequestrated carbon. Soil has always been at the heart of organic production, but there is now an increasing number of initiatives based on regenerative land management which seek to improve soil structure and health. There is no clear single definition of regenerative farming and many initiatives still rely on the use of herbicides and other inputs, but the change in emphasis is welcome.

This book not only builds on the very solid foundation of its predecessor, but also takes account of all the developments that have happened since. It is detailed and thorough and has drawn on the experiences and knowledge of a number of successful growers in different parts of the UK. It is also informed by research projects, many of which have been conducted in collaboration with growers. Another major source of information is the seriously impressive body of work contained in the 60-plus editions of The Organic Grower, all edited by the author.

This will probably be first and foremost a valuable reference book and should be essential reading for anyone starting out on the journey of commercial organic vegetable production on whatever scale. That said, there are also new things for old hands to learn, so the book should find its way on to a shelf in every packing shed and office in the country. It should not gather dust, but become well-thumbed as the seasons turn.

Roger Hitchings

Chapter One

Principles and Approaches

This is a book written for growers, or prospective growers, of organic vegetables for sale. The organic growing community is a ‘broad church’ and the ‘organic’ word can be off-putting for some. Many growers prefer to use other terms, such as agroecological, regenerative, biointensive and permaculture, to name but a few. There are zealots in every camp, but they have more in common than what separates them. It is essential to look at the principles rather than the jargon and for every grower, farmer or community to find the system that works best for them. It is the ‘how’ of applying those principles in practice that is important and examples of best practice will be given throughout this book.

Harvesting carrots at Sandy Lane Farm, Oxfordshire. Precision sowing with an air seeder means that the carrots have the right space to grow for optimum size and yield, with no need for thinning.

Organic is not a trend or a fad, but a legally recognised system of food production. There are guidelines and regulations which may scare off those distrustful of authority, but they are there to protect the consumer and the grower from the fraudulent. It should also be noted that standards are a baseline and organic growers should – and mostly do – strive to improve their systems ecologically. Historically, growers played a huge role in the setting up of organic standards in the UK. Standards have evolved, but have always been a pragmatic representation of what was achievable on the ground. While some might argue that the standards have not evolved fast enough to eliminate or reduce contentious inputs, such as the use of peat, copper and plastics, or to include social and ethical dimensions, they are still useful as a starting point and as guidelines. However you choose to define yourself as a grower, please approach this book and your growing journey with an open mind and try to avoid dogma!

The sun doesn’t always shine, especially in west Wales! Leek harvesting in the rain at Troed y Rhiw Farm, Llwyndafydd.

Embarking on a career as a grower can be a romantic notion. It can be, and might seem to others, a lifestyle choice. It is true that there are rewards to be gained from working in the fresh air, combining the joys of nature with the production of wholesome healthy food to be sold to a satisfied customer. But the sun doesn’t always shine and growing is not without its stresses. Once in the hurly-burly of the season, it can seem relentless. Climate change is making the weather less predictable and the risks of losing crops to extreme weather events and/or pest and disease outbreaks are increasing.

Growing has its fun moments, though.

There is also a huge amount of complexity involved with growing crops agroecologically. It is all about diversity – but that diversity demands an extensive knowledge of a large number of crops. Add in agroforestry, intercropping and perhaps livestock to the mix and the interactions between all those elements, and you have an organisational nightmare or a productive paradise, or maybe both! For that reason, this book focuses not only on the technical aspects of nurturing a healthy soil and bountiful crops, but also on the human side of vegetable production. The grower’s health and that of their family and employees is as vital for sustainability as the health of the soil.

The heart of the grower

The business of growing, as opposed to gardening or farming, is unique in terms of the relationship with the land and the direct contact with the soil and nature in addition to food production. Experienced grower Tim Deane expressed this eloquently in the first issue of The Organic Grower magazine in 2007:

Where is the grower in the scheme of things? Not a gardener, though we both grow plants, nor yet a farmer, though we both make our living from the ground.

Although in biodynamic practice and elsewhere commercial fruit and vegetable production may be characterised as ‘gardening’ and the term ‘market gardener’ is sometimes used, the divide between gardening and growing is simple and stark. One is a leisure activity, the other isn’t. One is the pursuit of freedom, the other more a matter of survival. The impetus that leads to both activities may be the same, but the moment the notion of profit and loss appears the path forks, and the two ways soon lose each other.

Farmers and growers both make their living from the land. Alike we are caught up in the rhythms of the world, moving perforce to its humours and its seasons. We live on and with the land, while the rest of humanity seems merely to occupy it. We come to recognise its meaning and its mysteries even if we cannot pin them down, whereas the non-agriculturist sees only entertainment, decoration or a space to be passed over. In the face of this incomprehension, farmers and growers must surely stand in pretty much the same place.

And yet, and yet … Of course, there are farmers who grow vegetables and growers who keep stock, but away from the edges, when you look at the two professions side by side and (as it were) en masse, there is a gulf between them. There may be some sympathy, but there is limited understanding. The differences all flow, I think, from the scale on which we work. A grower can make do with an acre or two (given enough plastic), whereas a farmer may just get by on a hundred acres and its subsidies, so long as his wife goes out to work. Scale implies status. It also has a huge effect on how we view the world.

Go to a farm sale and to a horticultural sale and you will see the difference right there – in the car park! In the one – Land Rovers, four-by-fours and macho pick-ups. In the other – battered vans. If you go further, you will see that the average weight at a farm sale is about two stone more than that at a grower sale. There will also be more beards at the latter, probably a lot more. And so on.

A grower might look on livestock as a literal waste of space; a livestock farmer tends to see vegetables, immobile in a field, as inanimate objects; the arable man’s cereal crops are composed of plants beyond reckoning, each living and dying in perfect anonymity. The difference of scale runs all through this. Grass grows without much effort. It has to be managed, a matter of skill, but it doesn’t have to be delved into. Just as well if several hundred acres are being farmed together. An arable field may only see a human presence for five or six days in the year. The value of what it produces may justify no more than that. If it wasn’t for the need to relieve themselves, today’s ploughmen could go from morning to night without their feet touching the ground.

The grower cannot live like that. The plants we grow may not move around, but the skill that brings them to life and husbands them through it is not different in essence to that entailed in stockmanship. Empathy, observation, attention to detail and not leaving things to chance – these are the same in both cases. Arable crops need space if anything is to be made of them. It’s not just that there has to be a lot of them to add up to any value. The wind cannot weave its dance over a few square yards of barley. Even the swede is only really happy if it has enough of its kind around it to take up an acre or two. But horticultural crops are tame and with it tender. They demand attention and understanding. At least at stages in their life they are individual and distinct – as seed, transplant, harvested root, fruit and the rest of it. To make a place for them and to bring them to conclusion, the grower has to enter into the soil in which they root as well as to live the weather in which they grow.

While the farmer scans broad acres from his tractor seat, the grower is down on the ground and cannot live without the earth getting under his fingernails. I wouldn’t say one is better or more valuable than the other. I do think though that, as farming is now, it is the grower who best preserves that vital link of mankind with the earth and its processes. The sun’s energy, photosynthesis and the cycling of carbon – this is the basis of all life. In the growing of plants organically lies its truest human expression.

Organic principles

Organic standards are guided by the principles and so should you be! Organic farming can often be defined or perceived by the negative – what you are not allowed to do, what is not permitted to be used and so on. I have heard growers say that they did not have a full grasp of what ’organic’ was until they started down the road to certification and had to read the organic guidelines and standards. Understanding ‘organic’ is about recognising the wholeness and interconnectedness of the system.

After three years’ work by a task force, IFOAM – Organics International came up with the following definition of organic agriculture:

Organic agriculture is a production system that sustains the health of soils, ecosystems, and people. It relies on ecological processes, biodiversity and cycles adapted to local conditions, rather than the use of inputs with adverse effects. Organic agriculture combines tradition, innovation, and science to benefit the shared environment and promote fair relationships and good quality of life for all involved. [IFOAM General Assembly, 2008]

IFOAM has also identified four principles of organic agriculture: The Principles of Health, Ecology, Fairness and Care. These are interconnected ethical principles composed to guide the global organic movement in policy positions, programmes and standards.

Organic growing is demonstrably so much more than the avoidance of artificial fertilisers and pesticides. By embracing the principles, organic growers can design systems from the ground up. If coming from a conventional growing or farming background, the biggest challenge can be converting what’s between the ears. Rather than thinking; ‘What product am I allowed to use to kill slugs instead of Product X?’, the approach should be ‘How can I redesign my system so that slugs are less of a problem?’

1. Principle of health

Organic agriculture should sustain and enhance the health of soil, plant, animal, human and planet as one and indivisible.

2. Principle of ecology

Organic agriculture should be based on living ecological systems and cycles, work with them, emulate them and help to sustain them.

3. Principle of fairness

Organic agriculture should build on relationships that ensure fairness with regard to the common environment and life opportunities.

4. Principle of care

Organic agriculture should be managed in a precautionary and responsible manner to protect the health and well-being of current and future generations and the environment.

Towards farmer principles of health

The farmers’ principles of health as set out here are the results of the Health Networks project, conducted 2015–16. It was funded by the Ekhaga Foundation, Sweden, and led by the Organic Research Centre, UK; the Humboldt University Berlin, Germany; Leibniz Centre for Agricultural Landscape Research, Germany; and the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Austria. Over a period of two years, a group of sixteen farmers (including growers) from Germany, Austria and the UK identified their own principles of health in organic agricultural systems. The farmers have established personal philosophies and strategies of best practice that make them successful in running healthy farms and producing healthy food. In this context, ‘farmers’ and ’growers’ are synonymous.

Statement 1 – Soil health

Farmers who aim to run healthy farming systems are aware that soil health is fundamental and the base for health in all other domains: plant, animal, human and ecosystem.

Statement 2 – Biodiversity

Farmers who aim to run healthy farming systems recognise and closely observe changes in biodiversity (particularly earthworms, farmland birds, bees and beneficial insects); and they aim for high and increasing biodiversity in their system, which contributes to the function of the agroecosystem.

Statement 3 – Systems thinking

Farmers who aim to run healthy farming systems are aware of working in and with nature’s systems and feel that best health is achieved when all domains are included according to their being, as part of the agroecosystem: soil, plants, animals and humans.

Statement 4 – Observation skills

Farmers who aim to run healthy farming systems develop the ability to closely observe key health-related processes on their farm and react appropriately; they have a good overview of the system.

Statement 5 – Intuition and self-observation

Farmers who aim to run healthy farming systems develop the intuition and ability for self-observation (for example, daring to listen to an inner voice or gut feeling) as part of the observation process of the farm; and they are aware of their own strengths and weaknesses and know their own resources and those of the farm (for example, social network, basic trust).

Statement 6 – Overview

Farmers who aim to run healthy farming systems ensure the manageability and overview of land and processes (diversity, integrity and sustainability), their responsible organisation (design) and optimal organisation of capacities on the farm, so that the complexity and size of the farm does not negatively affect health (also social and societal health). Different scale farms require different processes and organisational structures to achieve health.

Statement 7 – Long-term thinking and acting

Farmers who aim to run healthy farming systems improve health by planning in an increasingly broad and long-term perspective of the system. For example, through long rotations, perennials, habitats for wild animals, hedges or trees (generational structure and thinking).

Statement 8 – Shifting goals

The main goals of farmers who aim to run healthy farming systems shift away from mass production towards quality production. In place of maximising productivity (for example with high performance breeds), optimal yields are aimed for. By selecting appropriate breeds and varieties suitable for the site and the farm, qualitative values and multiple outcomes can be achieved; such as quality, optimum yields, resilience, animal welfare, biodiversity, etc. Aiming for high productivity when it comes to achieving multiple outcomes.

Statement 9 – Impart health

Farmers who aim to run healthy farming systems are aware that they not only contribute to human health through their high-quality food products, but that they also deliver highly valuable outputs in other areas (for example, environment protection, public goods, cultural landscape, water quality and so on). They get across the story and value of the product and the farm through close communication with, and involvement of, customers, consumers, retailers, processors and so on.

Statement 10 – Indicators

The most apparent indicators of health on the farm are (in alphabetical order): biodiversity; economic sustainability (financial viability); external inputs; food quality; health of people on the farm; number of veterinarian visits and treatments; plant vitality; soil fertility; soil workability; weeds; pests and diseases; and yield.

Shades of green – approaches and philosophies

Regenerative agriculture

Regenerative agriculture is becoming a trend and there are many farmers or growers who prefer to call themselves regenerative rather than organic. The term has been around for a while, but has recently gained traction due to its emphasis on soil health. But what is regenerative agriculture?

Groundswell’s five principles of regenerative agriculture.

According to the Regenerative Agriculture Initiative, California State University and The Carbon Underground: ‘ “Regenerative agriculture” describes farming and grazing practices that, among other benefits, reverse climate change by rebuilding soil organic matter and restoring degraded soil biodiversity – resulting in both carbon drawdown and improving the water cycle.’

The five principles of regenerative agriculture are summarised below, with my comments:

1.Minimising soil disturbance. The degree that this principle is adhered to can be a point of difference between some regenerative farmers who insist on no-till (and use of the herbicide glyphosate) and organic practitioners. There are, however, many successful examples of no-dig horticulture and systems that reduce tillage on a rotational basis.

2.Keeping the soil covered. Growing crops or stubbles will protect the soil from the impact of heavy rain, sun or frost.

3.Keep living roots in the soil. Living roots protect the soil from erosion – therefore cover crops are grown between cash crops, retaining nutrients and providing food for soil microorganisms.

4.Maximising plant or crop diversity. The more diversity in the system, the more resilience to pests and diseases.

5.Integration of livestock. Livestock provide a source of organic matter, encourage new plant growth, create more carbon in the soil and drive nutrient recycling by feeding biology.

The term ‘regenerative organic agriculture’ was first coined by Robert Rodale (son of the founder of the Rodale Institute) in the US to recognise that farming should do more than just be sustainable. Some say that regenerative agriculture is ‘beyond organic’, but there is much of regenerative agriculture that is integral to organic farming in its truest expression. In the US, companies like McDonald’s, Cargill and General Mills have jumped on the regenerative agriculture bandwagon. It makes good PR. Perhaps sensing this corporate encroachment, in 2018 the Rodale Institute went a step further and introduced Regenerative Organic Certified (ROC): ‘a new, holistic, high-bar standard for agriculture certification’ overseen by the NGO Regenerative Organic Alliance. The ROC takes the USDA Certified Organic standard as a baseline and adds: ‘criteria and benchmarks that incorporate the three major pillars of regenerative organic agriculture (soil health, animal health and social wellness) into one certification’.

Stockfree organic

In contrast to regenerative agriculture, stockfree organic agriculture excludes animals or animal by-products from the farming system. It is partly a response to the difficulties in providing fertility through organic manures from within the farm, but it also coincides with the growing vegan movement and the demand that products vegans consume do not support livestock farming.

Iain Tolhurst of Tolhurst Organic, near Reading, has been a pioneer of vegan organic systems.

Stockfree organic systems aim to provide fertility through green manures and composts where livestock manures are not available; many stockfree organic farmers choose to farm without livestock for ethical reasons, as well. There are issues beyond the ethical concerns, with potential risks to human health from antibiotics and other drugs in manures – less an issue in organic farming – but the use of manure from non-organic (but not factory) farms is allowed in organic standards under certain conditions. Of course, animals can’t ever be excluded completely from a system and stockfree organic growers could be considered farmers of earthworms and other below- and above-ground fauna.

The emphasis is on a systems-based approach. Stockfree organic standards have been developed and are currently certified by the Soil Association. There are currently two sets of standards: the Biocyclic Vegan Standard approved by IFOAM and supported by the International Biocyclic Vegan Network in Germany; and the stockfree organic standards held by the Vegan Organic Network (VON) in the UK. Both standards operate above and beyond the existing organic standards.

The first stockfree organic standards were developed by VON in the UK in 2007 and encourage practices promoting soil fertility and health through the use of plant-based inputs, such as compost and green manures, aligned with a well-designed rotation.

The Biocyclic Vegan Standard is based on the work of the German pioneer of organic farming, Adolf Hoops (1932–99). It takes a holistic approach, with an emphasis on using mature compost and humus, closing loops, working with nature and caring about the whole food chain.

Natural agriculture: Shumei and Korean style

The concept of Shumei Natural Agriculture was developed by the Japanese naturalist and philosopher Mokichi Okada in the 1930s in Japan. According to Okada, ‘The principle of Natural Agriculture is an overriding respect and concern for nature.’ Naturally, that precludes the use of fertilisers, but not just artificials – the belief is that any fertiliser inhibits the soil’s natural ability to enrich itself. Soil is considered ‘perfect’, containing all that is needed for healthy plant growth. Health starts with healthy soils. The use of ‘natural compost’ is permitted; it is not considered a fertility input, but is used for improving the soil temperature, keeping the soil ‘temperate’, and for ‘softening the soil’. The principle of consciousness guides all life processes and extends to all that grows. Pests are not considered as such, with the principle of non-intervention extending to the prohibition of organic pesticides.

Shumei Natural Agriculture at Yatesbury, Wiltshire, with brassicas continually grown in one place.

The most challenging aspect of Shumei Natural Agriculture is the absence of rotations. Continuous cropping allows crops to become accustomed to the soil they grow in and their wider environment, with plants building up resistance to pests and diseases. Seed-saving and adaptation is an important part of this. Science is starting to reveal how the seed biome adapts to its environment over time and we are learning more about mycorrhizal associations with crops, which can help to explain to an extent how these systems can work.

As with biodynamic farming, spirituality is integral to the philosophy, as is a pure mind, gratitude and humility. A caring attitude towards the soil and crops is key – water and soil respond to our hearts, according to Shumei Natural Agriculture precepts.

Korean Natural Farming (KNF) was developed in the 1960s by Dr Cho Han Kyu, who was influenced by the natural farming movements in Japan. The emphasis is on closed systems, limiting external inputs and recycling wastes on the farm. An important aspect is a focus on indigenous microorganisms (IMO), which are collected from woodland on site and nurtured with sugar and fermented plant juices as ‘microbial seed for your land’. There are growers in the US and in the UK and Ireland who are adapting these methods, using local plants such as comfrey and nettle, fermented according to KNF guidelines.

Biodynamic agriculture

Biodynamics is claimed by the Biodynamic Agriculture Association to be the oldest defined system of organic growing. It has its roots in a series of lectures entitled ‘Spiritual Foundations for the Renewal of Agriculture’ given by Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner in 1924. According to Steiner, ‘life forces’ in the crops and animals also sustain the vitality of the person who eats the food. The use of chemical fertilisers reduces the vitality of the crops, he believed, so it is therefore important to increase soil life, with the use of composts and manures creating a biologically dynamic agriculture.

One of the best-known biodynamic preparations involves fermenting cow manure inside a cow horn that has been buried in the soil over winter.

Steiner introduced six herbal preparations for use on the compost heap and two additional preparations for spraying on the fields to increase vitality of the soil and crops. One of these is derived from manure buried in a cow horn during winter (500) and is designed to enhance the powers that come from the earth. The other (501) is made from a quartz crystal that is buried in the summer and said to be subject to the metabolic forces of soil life and the cosmos. A well-known aspect of biodynamics is its adherence to the rhythms of the sun and the moon – for example, planting by the moon.

Perhaps the most significant concept that Steiner introduced, and easier for the scientifically trained to grasp, is that of the ‘farm organism’. Farms should be self-contained, mixed with livestock and with as far as possible closed nutrient and energy cycles. This can be problematic for horticultural units due to a higher land requirement unless part of a wider biodynamic farm.

Whatever you may feel about some of the more esoteric aspects of biodynamics, or misgivings you may have about some of Steiner’s beliefs, farms practising their methods are often well run, with vibrant, healthy crops and animals. In the UK they come under the umbrella of organic certification, with additional requirements governed under Demeter certification.

Permaculture

Permaculture is a contraction of not only Permanent Agriculture but also Permanent Culture and was developed as a concept by the Australian Bill Mollison in the mid-1970s. He described it as a:

design system for creating sustainable human environments. Permaculture is based on the observation of natural systems, the wisdom contained in traditional farming systems, and modern scientific and technological knowledge. Although based on good ecological models, permaculture creates a cultivated ecology, which is designed to produce more human and animal food than is generally found in nature.

The principles are sound: the use of polycultures (many species of plants and animals together); plant stacking (making use of different levels: trees, bushes, herbs); time stacking (starting one crop before another is finished); perennial vegetables (resilient and less soil disturbance); efficient energy planning; and energy cycling. It is the application of these principles to viable commercial production that can be challenging.

The foundations of permaculture are the ethics (centre) which guide the use of the twelve design principles, ensuring that they are used in appropriate ways. These principles are seen as universal, although the methods used to express them will vary greatly according to the place and situation.

Agroecology and Food Sovereignty

It has become common for growers who choose not to certify their holdings organically to describe themselves as agroecological growers. Agroecology has a comparatively wider meaning, but according to the UK Statutory conservation, countryside and environment agencies’ Land Use Policy Group (LUPG) report, The Role of Agroecology in Sustainable Intensification: ‘The term agroecology has been popularised more as an approach emphasising ecological principles and practices in the design and management of agroecosystems, one that integrates the long-term protection of natural resources as an element of food, fuel and fibre production.’

Agroecology is based on applying ecological concepts and principles to optimise interactions among plants, animals, humans and the environment, while taking into consideration the social aspects that need to be addressed for a sustainable and fair food system (FAO).

It was not until the early 1980s that agroecology became a discipline named by ecologists, agronomists and ethnobotanists. In essence, it encompasses all of the above approaches including organic farming, but more recently it has also been associated with more radical perspectives and linked to peasant agricultural movements such as La Via Campesina in South America.

There is a danger that the term could be hijacked by corporations as ‘green wash’, in the same way that some say the term ‘sustainable agriculture’ has been, and thus become meaningless. Indeed, in France the term ‘agroecology’ became a battleground in 2012 between the French Government’s form of agroecology, which encompassed no-till methods with herbicides, and the version favoured by civil society organisations and small farmers, that is, a diversified organic agriculture on a human scale. Many argue that agroecology must go hand in hand with food sovereignty to enable transformation of the food system. La Via Campesina defines food sovereignty as:

The right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems. Food sovereignty puts those who produce, distribute and consume food at the heart of food systems and policies rather than the demands of markets and corporations.

Chapter Two

It’s All About the System

The system of production arises out of the principles outlined in the previous chapter, but it also relates to scale and to market. System design needs a degree of pragmatism and flexibility as ecological and commercial realities come into play, interacting with the individual circumstances of the particular holding. Certification, through adherence to standards, provides boundaries to the extent to which compromises can or should be made. The good grower will be continuously evaluating the functioning of their system and striving to improve it.

Teign Greens, near Exeter, is an 80-member Biodynamic Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) veg-box scheme established in 2020, growing on roughly 1.5ha and using a mixture of methods from min-till with compact tractor to no-dig via a BCS walking tractor, As well as the CSA, they wholesale salad and greens to local pubs, retreat centres and so on, based on a larger 22ha mixed farm.

Sometimes more than one system can be employed on one farm. For example, a holding might have a bio-intensive no-dig system operating in polytunnels, an intensive market garden using a bed system and two-wheeled tractor, wheeled hoes and seed drills, plus field-scale vegetables with tractor-operated cultivations, planting, weed control and harvest. The intensity of the system and the degree of mechanisation is to an extent determined by the market and the value of the produce. If you are direct marketing and planning to grow all crops yourself, then you may need different systems – growing maincrop potatoes for hand harvesting on a no-dig system makes no commercial sense.

From market garden to field-scale production

Bio-intensive production

There is nothing much new under the sun and intensive bed systems are not new. Alan Chadwick in the 1960s in California and later John Jeavons in How to Grow More Vegetables than You Ever Thought Possible on Less Land than You Can Imagine advocated the biodynamic/French intensive method of horticulture. They drew inspiration from the French intensive techniques employed in the market gardens surrounding Paris in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Crops were grown in 45cm of horse manure, which was readily available, and spaced closely together to exclude light and weed growth and to conserve moisture. Glass bell jars were used to provide individual cloches for winter and early crops. Using these techniques, up to nine crops per year could be grown.

Chadwick and Jeavons also drew on the biodynamic techniques of Rudolf Steiner, particularly the holistic growing environments of plants and their various companion relationships. Chadwick made a barren garden at the University of California – Santa Cruz fertile, using large quantities of compost. One technique he employed was to ensure that seedlings were always transplanted into progressively better soil, as well as sowing and planting by the phases of the moon. Yields were said to be four times higher than those produced by commercial growers. Jeavons describes biodynamic gardens using raised beds 90–180cm wide, themselves inspired by Ancient Greek observations of how plants thrived in landslides, with loose soil allowing air, warmth, nutrients and roots to penetrate the soil properly. Jeavons’ system does involve double digging when setting up the beds, followed by the use of a U-bar – which has now come to be known as a ‘broadfork’.

Broadfork with intensive beds, mulched with compost at Trill Farm Garden in Devon.

No-dig or minimum tillage

The model of growing food in undisturbed soil, thereby preserving soil structure and encouraging the absorbance of water and carbon while allowing soil health to flourish, is key to its appeal, coupled with the human scale of production and the possibilities of establishing a holding without huge investments in machinery. No-dig/no-till allows the soil biology to be more active and can help plant roots to find nutrients that are already in the soil. The mycelial network remains intact and serves as an extension to plant roots. Using compost on undisturbed soil is about feeding and encouraging the work of these valuable organisms.

Trill Farm Garden. Ashley Wheeler and Kate Norman have been running Trill Farm Garden since 2010. In 2022, they took on an additional hectare on top of the original 1ha market garden.

Charles Dowding has been a long-term practitioner of no-dig growing and his early systems involved initial cultivations with a rotavator, followed by bed-forming by hand using a spade. The system he has developed since 2000 at Lower Farm and now at Homeacres in Somerset involves laying cardboard on the ground (usually mown pasture), with 7–15cm of composted material on top. He is experimenting with different amounts and types of compost, including woodchip, and currently makes two-thirds of the compost he uses.

Setting up no-dig beds at Sandy Lane Farm.

At Homeacres, the health of the crops, the lack of weeds and the reduction in hard physical labour are evident. The ongoing comparative trials (not replicated) between a dig and no-dig bed consistently show yield advantages for the no-dig system. It is, however, not a certified organic system and the use of cardboard plus the quantities of brought-in manures entails some challenges both for certification and for scaling-up to a commercial scale.

Inspired by Charles Dowding, many growers have adopted no-dig beds in protected cropping, or in intensive plots for high-value crops, such as salads.

More recently, growers have found inspiration in some of the (mainly) North American growers with intensive no-till market gardens. There are, though, a few notes of caution that should be raised. The North American models may not be replicable in UK conditions in terms of returns and profitability (for example, Curtis Stone’s claim of being able to make $100K/year profit off his 0.1ha urban farm), as they are very reliant on a large urban market. Also, the systems depend on large inputs of manure or compost from off the farm, particularly when starting out. In the same way that the French bio-intensive growers of old relied on supplies of horse manure, the modern no-till grower may use green-waste compost from municipal composting, or manures from horse stables and livestock farming. This can be considered as ‘closing the loop’ by allowing the return to the land of nutrients that might otherwise go to waste. However, there is an ongoing debate about the addition of what some consider to be excessive amounts of organic matter and nutrients, and the problems this can cause (seeChapter 5).

Ghost acres

The term ‘ghost acres’ was coined in the 1960s by Georg Borgstrom in his book The Hungry Planet to refer to the area of land abroad that is used to grow feed for animals within a country. In horticultural terms, it relates to the land outside the holding that is producing the nutrients imported into the system. This can take many forms, not just the feed for animals on the holding, but also the manure, straw or mulches that are imported, which also need land to produce them.

Pedestrian rotavator/two-wheeled tractor

In the hinterland between the intensive no-dig market gardens and field-scale production lie intensive systems based on pedestrian rotavators, two-wheeled tractors or compact tractors. A little bit of mechanisation, though anathema to some, can enable a larger area to be managed by one person.

Two-wheeled tractors are mainly used for cultivations – preparing the ground for seedbeds and planting – but they can also be fitted with a range of implements for mowing, chipping and carting. A pedestrian rotavator or two-wheeled tractor can be used comfortably on cultivation areas up to 0.7ha, with much lower running and maintenance costs than a tractor and hence a lower carbon footprint. The easy creation of seedbeds enables seed drills to be used for precision sowing and row marking for efficient use of wheel hoes for weeding. Precision saves time when thinning crops, while optimum spacing maximises yields and quality, reducing wastage. The system lends itself to growing in plots rather than beds, though some systems have fixed paths, with the rotavator used to till narrow beds the width of the rotavator.

Jason Horner of Leen Organics in County Clare, Ireland, using a two-wheeled tractor with ridging attachment in potatoes.

It is advisable to get the most powerful model you can afford. Avoid tillers and cultivators that are powered on the rotors, as they tend to bounce and can be difficult to control and need a lot more physical effort to use. That is not good when using anywhere near or inside a polytunnel!

Compact tractor

A next step up is to the compact tractor. The advantages of small tractors are that, while good for seedbed preparation, you can expand the possibilities in terms of equipment like loaders for turning and moving manure and compost, fertilizer spreaders for lime, or broadcasting green manure and pallet forks for moving bulk bags around the holding. They are suitable for plot-scale growing, where a large field is subdivided into rotational plots.

Field-scale vegetable systems

Field-scale vegetable systems, where large plots or fields grow single crops, are normally associated with production for wholesale or packer (supermarket) sales. They are usually highly mechanised, with large capital inputs and economies of scale. There can be an assumption that these systems are not as agroecological as smaller intensive systems, but this is not necessarily the case. They can be every bit as focused on soil health and regenerative practices and are often very innovative in their approaches, for example the use of cover crops and integrated pest management.

A market grower may also have a few fields for growing the staples. It is still possible to source smaller field kit relatively cheaply and to grow staples profitably. There are indications that fewer new growers are coming into field production, plus there are fewer growers around with the necessary skills. Training and demystifying field-scale production is necessary, together with appropriate technology, if the gap between intensive market gardens and the supermarket growers, with increasing use of robotics and cutting-edge technology, is not to widen. There are opportunities, as well as a need for growers to work together through sharing machinery – for example through machinery rings – and planning field cropping strategically, something that UK growers have not always been good at doing.

Farmtrac FT25G HST electric tractor in demo at Grown Green in Wiltshire.

Field-scale vegetable production at Strawberry Fields in Lincolnshire.

Kate Collyns (Grown Green) rents 1ha at Hartley Farm near Bath. Kate grows on a mini-field scale for local wholesale, to the farm shop and kitchen on site, as well as to nearby veg-box schemes, shops and restaurants. She uses a Kubota compact tractor with a 1.5m rotavator for the field and a BCS 740 two-wheeled tractor for cultivating polytunnels and smaller patches. Planting is done by hand, sowing with an Earthway drill, and weeding with a wheel hoe.

Arable rotations with vegetables

While vegetables are normally grown on a vegetable holding with a permanent rotation, they can also be grown as part of a wider farming system, for example an arable farmer diversifying into vegetable production, or a grower entering into an agreement with an arable farmer to rotate vegetables around the farm. There are advantages for the grower, as the vegetables can be grown on ground that should be clean of pest and diseases.

It may be a few years before returning to the same field, which means that the usual need to balance crop families – there is often a need for more brassicas in the rotation than is healthy – don’t apply. If it is a share-farming agreement, then primary cultivations and muck spreading could be done by the farmer, meaning fewer machinery requirements. On the other hand, arable farms are less likely to have irrigation and electric fencing may be required to keep rabbits, badgers and the like out of the crops.

Mixed farming systems with vegetables

A mixed farm that includes grazing land might also incorporate arable and vegetable crops into the rotation. In mild coastal locations like Cornwall, mixed farms would traditionally follow (at least) three years of grass/clover with early potatoes and winter cauliflowers and a summer reseeding of the grass leys. Animal manure from grazing animals, normally dairy or beef suckler herds, would provide fertility.

Horse-powered vegetable growing

While for some the thought of powered machinery is scary, for others working with horses it is even more so! It may seem like a step backwards, but modern horse-powered vegetable farms combine new technologies with traditional ways. If you have an affinity with horses and the time and patience to learn the skills, it may be for you. A lot of the skills and knowledge about horse-powered systems come from the US, where there have been Amish communities keeping the skills alive.

The Pioneer Homesteader in use at Chagford CSA in Devon.

In the UK, there are very few horse-drawn implements available and you may have to look to Continental Europe or North America for appropriate kit. There are toolbars, such as the French-made Kassine, which can be fitted with a range of different tools for weeding, tilling and ridging. It can be pulled by a range of draft animals, with either flexible traction, whereby the carrier is linked to the tool by ropes or chains, or rigid traction using a shaft or drawbar. Other tool carriers are available, such as the German–Swiss developed Univecus, which has a combined steering mechanism that is useful on sloping ground, and the US Pioneer Homesteader, which is good for heavier duty cultivations with two light or medium-sized horses.