20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

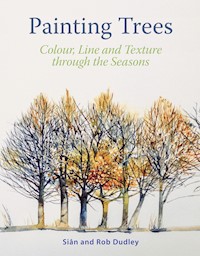

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Painting flowers is a joyful experience - to capture and celebrate the colour, form and beauty of flowers in watercolour is an endlessly exciting pursuit. This book encourages you to experiment and play when you paint, to enjoy the process of creating a painting, and to develop your own style as you observe and render either a single stem or a full floral abstract. By moving from the tight constraints of botanical illustration, it encourages a looser style of floral painting that allows for a more personal and unique interpretation of the subject. Contents include: Observational skills - the importance of looking closely at a subject to see detail in a new way; Understanding your materials and equipment - looks at traditional tools and paints, but also how photography and other digital media can be used to the artist's advantage; Inspiration and design ideas - suggest ways to express emotions by experimenting with colour, shapes, concepts and narrative. Demonstrations, exercises, studio tips and projects guide the way, but the book's emphasis is on developing your own ideas and styles through creative experimentation. Beautifully illustrated with 273 colour images.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 331

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Painting Flowers

– a creative approach

SIÂN DUDLEY

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2018 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2018

© Siân Dudley 2017

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of thistext may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 372 1

Dedication

For Rob, for Purple Pansy Sunday and for your patient and loving encouragement in the many years since.

Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1 Creativity in flower painting

Chapter 2From illustration to invention

Chapter 3The studio and equipment

Chapter 4Positive steps towards artistic freedom

Chapter 5Gathering information

Chapter 6Designing a painting

Chapter 7Botanical art: paintings of the flower

Chapter 8Floral art: paintings about flowers

Chapter 9Moving towards floral abstracts

Further information

Index

Introduction

I knew I had found my ideal medium the very first time I painted with Artists Quality watercolours. I was painting a deep purple pansy, freshly picked from my garden. I mixed the colour on my palette, and carefully placed it onto a dampened area of paper. What happened next quite literally took my breath away. As the colour flooded across the paper I gasped, and my knees went weak. I knew instantly that this was the medium I had been looking for. That was many years ago now, and I can scarcely believe that I still have the same reaction. Watching paint move with a will of its own, and the brilliance and clarity of bright fresh colours, still causes an involuntary intake of breath. Sometimes when I am demonstrating I have to concentrate hard to stop my knees buckling.

The Purple Pansy; a life changing painting.

Like many artists, I can genuinely say I have always drawn and painted. It is an impulse which I have found impossible to ignore; it just has to be done. The day just doesn’t feel complete without creating something, and the best days are when that something is a painting or drawing.

Growing up in a science-based household, my artistic nature was encouraged, but not fully understood. Art was considered a hobby, not a need, and despite my father’s valiant attempts to aid me in my interest, the finer points of art and art materials were missed. Science ‘won’ and my fascination with detail and wanting to know how things work finally led me to a degree in Microbiology. Thankfully this involved hours and hours of drawing. These were very precise, descriptive diagrams, focussing on tiny details and an accurate representation of the plant or animal we were studying. It called for intense observation, but any form of artistic expression was strictly forbidden. In spite of this I enjoyed every moment of making these drawings, from developing an ability to notice each tiny feature of my subject to learning to control my pencil to join two lines so that the join was invisible. This of course is the basis of botanical illustration, the purpose of which is to record a plant carefully and accurately in order that the illustration could be reliably used for identification purposes.

And so to the plants. I love flowers! I love the colours, the shapes, the way they move, the architectural qualities, the softness, the play of light on and through petals and the kinetic qualities of their shadows.

Oh, and the scents. The wonderful scents! There is a saying that you can hear an excellent landscape painting, because you are transported into it; imagining yourself standing there, you can hear the sounds that would be present. Wouldn’t it be wonderful to similarly transport the viewer of a floral painting to imagining themselves picking up the flower and being able to breathe in the delicious scent?

When I acquired my first garden, it was quite natural for me to draw and paint the flowers I grew, and very natural to continue in the botanical illustrative style I that I had already developed to quite a high standard. But now I could add colour, which was very exciting. I experimented with all sorts of materials, some very interesting, but none that thrilled me.

The afternoon I painted the pansy quite literally transformed my life. I had discovered a medium that gave me the opportunity to mix the exact colour I wanted, very easily. More than that, the watercolour seemed to have a life of its own, which was very exciting. It did unexpected things at unexpected times. Frustrating, of course, but I saw that as an exciting challenge. My initial interest in colouring the illustrations quickly developed into an exploration of the medium itself. The more I experimented and explored, the more exciting it became, until I realized that I had reached a point where it was the medium, not the subject matter, that was leading my decision-making when I painted. My paintings were no longer tight botanical illustrations, but much looser flower paintings. The subject matter was still recognizable, but the painting was now also about the paint and the painting process, not just the flower. My paintings were no longer a celebration of flowers in paint, but a celebration of flowers and paint.

In my very brief time as a scientist, I was trained to design experiments and analyze the results, and I think when my painting started to evolve from a tight illustrative style to a looser, freer style, I was instinctively adopting this same approach. That degree had to be useful for something as I never worked as a scientist, instead becoming a teacher, and very quickly finding myself teaching art.

I have often heard artists who paint detailed figurative work expressing the idea that they would like to paint more loosely, but have no idea how to go about it. Further questions establish that the person I am speaking to has attempted to make a leap from figurative painting to a much looser style. Experience has shown me that leaps of this kind, without a thorough understanding of techniques, rarely results in success. I have also discovered that many people feel that they ought to paint in a loose style; not only do they not know how, they are not even really sure that they want to. It saddens me to see enthusiastic artists embark on an exciting voyage of discovery, only to be thwarted by either dogma or an ill-considered approach.

I realized that through the evolution of my own work, I had developed an approach to painting that readily allowed transition from one painting style to another, whether in the usual direction from tight to loose, or the other way around. Having an analytical mind means that I have developed a considered approach to design, which has helped enormously in making decisions about style and freed me creatively. Taking time to think before and during painting actually speeds up productivity, because the chances of success are so much higher.

This book will guide you through this approach. The approach laid out here is for anyone who would like develop their own painting, whether you wish to change your style, or you are comfortable with your choice of style but would like to improve your painting ability. Obviously in this book I will be sharing my passions for watercolour and painting flowers, but you will find that the approach itself is applicable to any subject matter and any medium.

Much of it will be familiar; as you will see in Chapter 1, I do not believe it could be otherwise. What I think might be different is that rather than simply list a set of techniques for you to practise, or exercises for you to follow, you will be asked questions that will help you to consider your choices and decisions when you paint. Often solutions are found by knowing which questions to ask.

I have also noticed over my years of teaching art that it is often a lack of confidence, not a lack of ability, that holds people back. The desire to paint flows from somewhere inside of you; it is very personal. Keep this in mind as you go through the book. The right answers to the questions are your answers; trust them. You will be painting your paintings, not mine. I hope that you will find my approach helpful in building your confidence in your own work, so that you enjoy the process more and are happier with the results.

There will be techniques, exercises and examples too. You will also find demonstration pieces that you can work through. These should be used as stepping stones for your own work. You will also find lots of general tips for making painting easier. Whether you work through the book, or dip into the bits that are most useful to you, I hope it will help you to enjoy your painting more.

My own work continues to evolve, and I hope it always will. For me, the process of experimentation and discovery is endlessly exciting. I hope to be able to help you along your own path of thoughtful experimentation and discovery, and that for you also the process will become just as enjoyable and important as the finished image, if not more so.

Green Globes.

Chapter 1

Creativity in flower painting

Imagine for a moment the excitement of finding an inspiring subject that you are passionate about, and that surge of enthusiasm to begin painting immediately. How wonderful it would be to do just that! To paint freely, expressively, sensitively, with a sense of purpose and unadulterated joy. To allow your personality to show through in your paintings. To have the freedom to develop your own style. To paint the painting you want to look at. Are you smiling?

Every year since 1769, the Royal Academy of Arts has held an open exhibition in London. The RA Summer Exhibition aims to show contemporary art in painting, drawing, sculpture, printmaking, architectural models, film making and installations in one exhibition. Each year, thousands of hopeful artists submit their work, and over a thousand works are selected for exhibition.

Escaping Daffodils. Painted in response to seeing daffodils held in bunches by rubber bands and squashed into boxes in a supermarket. I painted this picture to express a desire to see them escape captivity and dance in the breeze under a spring sky.

What makes this exhibition so remarkable is the huge diversity in subject matter and variety of style and genres in the artwork exhibited. Ethereal figurative work is juxtapositioned with loud splashy abstracts, bold sculptures in strange materials are exhibited alongside delicately constructed architectural models. There is nowhere else on earth where it is possible to experience such a potpourri of artwork in one venue on the same day.

That is why, as an artist, one should visit this exhibition, and with an open mind. Walking through the galleries can be an adventure, a voyage of discovery. The number of paintings on display can be initially overwhelming, but you will very quickly find your eyes resting on the images that interest or excite you. But, do you like them? Could you live with them? Do you find yourself seeking out the familiar, or looking for surprises? Are they good? Do you question the selection committee’s choices? Why? What do you learn about your developing tastes in art?

For me, the most remarkable thread that runs through this exhibition every year, the one thing that every piece has in common, is confidence. The level of confidence on display at the RA Summer exhibition is encouraging, and freeing. The artist had the confidence to choose their subject matter and style, and to design the image they presented. The works themselves are confident in their execution. A whole committee of people liked it enough to confidently select it for exhibition. And a whole bunch of visitors will like it too. Some will not, but everyone is entitled to their personal taste.

Each time I visit, I leave with my own confidence boosted, because I am reminded that there is no right or wrong way to create a piece of art. There are as many ways as there are artists. There is my way. And there is your way, which is as valid as anybody else’s way. And that is exhilarating.

These pretty flowers were in a small pot on a garden table, where I was sitting drinking coffee. They fascinated me and I knew I needed to paint them, just for the sheer pleasure of it.

What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again, there is nothing new under the sun. Is there anything of which one can say, ‘Look! This is something new’? It was here already, long ago; it was here before our time.

Ecclesiastes 1: 9-10

VALUING YOUR CREATIVITY

Do you see a flower and just feel like you want to paint it? Is it as simple as that, the need to make an image of it? Or do you need to explore the medium, and you do that through painting a flower? Is it an inner feeling that you want to use your hands to make something? Or a desire to play with paint?

Nothing comes from nothing

Many people question their own creativity. A rather old fashioned but annoyingly prevalent and persistent definition of creativity implies that something is made out of nothing, and that the something created is completely new. It requires a good imagination, and the ability to come up with completely original ideas. This definition is so inaccurate it should be reclassified as a myth. Fledgling artists are often inhibited by this definition, feeling that unless they come up with something completely new, they are not being creative. We are all influenced by what has come before, by what has happened before, in art, and in our lives. It is impossible not to be. The lyrics from one of the songs in The Sound of Music are a lovely reminder: ‘Nothing comes from nothing, nothing ever could…’ , and a lovely little tune to hum in a moment of doubt.

A kinder and more accurate way of defining creativity is to see it as the ability to perceive the world in new ways, to notice patterns that others have missed, or to make new connections between apparently disparate sources, and in doing so to form something new. In the world of ideas, the something may be intangible, but in the world of art it could be a painting.

A mature artist will not only be aware that nothing comes from nothing, but will readily share the sources of their influences. The reality is that we build on what we know, because we cannot do otherwise. Do not overcomplicate the term ‘creative’. Instead, tune into your need to make something without worrying about it being completely new. Embrace the things that have influenced you, and learn from them.

If it has all been done before, why bother? You bother because you haven’t done it before. Your interpretation of it is as important as anyone else’s. There are few artists interested in painting flowers that have not attempted to paint a rose. Imagine the loss to our experience if Charles Rennie Mackintosh decided not to paint roses because Redouté had beaten him to it.

There is no one else quite like you. No-one else with your thoughts, who will make connections in the same way as you. No-one else with your hands, and your eyes; no-one else who can use them. So when you do that, when you co-ordinate your mind, your eyes, your hands and your heart, you are being original. You are the originality in the image, not the paint, not the techniques used to apply it, and not the subject matter. You have a desire to make a painting of what you find to be an inspirational subject. You are being creative.

Luckily there is a long history of floral art for us to draw on to inspire us and aid us in our creativity.

VARIETY IN FLOWER PAINTING

A tiny pot of delicate primroses.

It is rather an obvious statement to make that flowers play an integral part in our lives; so do lots of other things, but few commonplace things hold such a special place in people’s hearts as flowers. For beyond their usefulness in nature and their inherent beauty, the perfumes and the messages they convey have long played a part in cultures all around the globe. Little wonder then that flowers have provided inspiration for so many different artists, for so many different reasons.

Paintings of flowers display the same variety as the flowers themselves: intimate descriptive portraits recording every tiny detail of a plant; beautiful figurative paintings that transport you to a corner of a room filled with a vase of fragrant roses; soft gentle gardens full of fresh air and sunshine; bold energetic abstracts of bright red poppies; delicate portrayals of softly coloured primroses…

When asked what type of flower paintings you do, it can be difficult to describe the general style or genre of your paintings. Flower paintings seem to fall into categories, but beyond the well-defined genre of botanical illustration, the boundaries become blurred. It is far better described as a spectrum, with a gradual transition from one style to the next, and often considerable overlap between the different genres. For ease of communication in this book, I have come up with loose definitions of categories of flower painting.

Botanical art

Botanical art includes paintings which are intended to describe or record the morphological features of a flower or plant; these are essentially paintings of flowers. At one end of this category, the strong link with botanical illustration is evident, although the rules are relaxed as scientific accuracy is not a requirement. Stylistically botanical art is detailed and figurative. As botanical art moves along the spectrum of flower painting, there is room to explore the medium too, as long as it does not detract from the flower itself.

Spring Hedgerow. In this painting of a spring hedgerow, the flowers are instantly recognizable, despite the lack of ‘botanical accuracy’. The painting is about the abundance of life and energy in a spring hedgerow, the use of the medium reflecting this is in the energetic mark-making and vibrant colours. This image contains both figurative and abstract passages, with the medium being as important as the subject matter.

Calla Lilies. This painting of Calla lilies could be described as botanical art. It is clearly a painting of the flowers, encouraging the viewer to enjoy the colours and shapes, and drawing them in to discover detail they might have not noticed before.

Floral art

Floral art includes paintings that are about the flower. There is something about the flower that inspires a painting: it may be a physical attribute such as the colour, or the shape of the petals. It may be another characteristic, such as the way it moves in a breeze. It could be that the flower plays a role in a narrative; the painting is of a flower but there is a message or story involved. The medium itself plays a far greater role than in botanical art, and may even be the source of inspiration for a flower painting. Stylistically floral art is still quite figurative, but may also include elements of abstraction.

Floral abstracts

These paintings are inspired by flowers, sitting in a grey area between figurative painting and the abstract. The paintings are recognizably inspired by flowers, but are not representational of the flower itself.

This image falls into the category of Floral Abstracts. In this case, the inspiration is clear, as it is obviously inspired by a dandelion clock. It uses the spherical shape of the fluffy seedhead and the arrangement of the individual seeds, to the extent that the dandelion clock is recognizable, but that is where the resemblance ends. Closer inspection reveals that the motif of the dandelion clock is little more than a structure on which to base painterly marks, and to play with a variety of techniques. Glazing, salt and masking fluid techniques have all been explored to create a feeling of fluffiness, movement and energy. The pooling of paint within boundaries created by masking fluid are more suggestive of stained glass windows than a dandelion clock, and the choice of colours may bring to mind a starlit night sky. The viewer is invited to wander away from the obvious inspiration to an interpretation of their own.

Each category is of equal importance. Each has its own purpose. As you go through the book, please keep in mind that each of these falls somewhere along the spectrum of flower painting. There are paintings that fit neatly in a particular category, but also many that would be difficult to place in one category rather than another. Where a painting sits often depends on the perspective of the viewer; a painting that the artist describes as floral art might be perceived as botanical art by someone who paints in an abstract style, but as abstract art by someone who paints in a botanical style. Equally important is the intent of the artist; do they intend to make a painting of the flower, about the flower, or inspired by the flower?

All of this is not a matter of learning to define your art, which sounds restrictive and might inhibit creativity. It is more a matter of understanding what you are trying to achieve, and using that knowledge to free your creativity.

This diagram of a dissection of a stylized flower shows the botanical names for the parts of a flower. Botanical illustrations include this type of detail for each specimen, painted with extreme accuracy. Although not needing to understand plant structure to this degree, flower painters will find their powers of observation improved and their enjoyment of painting enhanced by gaining a basic knowledge of botany.

A note on botanical illustration

Botanical illustration has firm roots in science, and is subject to strict rules enabling these illustrations to be part of an international scientific language. The purpose of botanical illustration is to ensure accuracy of identification to species level (which, let’s face it, could be life-saving). The illustrations have to be botanically accurate, recording all aspects of the life cycle, and may include drawings of dissections, or illustrations of the plant in its natural habitat. The plant is depicted in a generalized form, ignoring any imperfections of individual specimens.

The best botanical illustrations can be very beautiful, giving considerable thought to composition so that they are visually appealing. It is impossible not to be in awe of the artist’s dedication to fine detail and technical skill. Just as the plants must be portrayed in a generalized form, there is no room at all for artistic expression or for the personality of the artist to show through. Botanical illustration is very much about the plant; the image itself is of secondary importance. For an artist with an interest in botany and fascinated by details, making botanical illustrations can be absorbing and deeply satisfying.

Despite botanical illustration being carried out by highly skilled artists, and its worthy and lasting influence over the way flowers and plants are painted, its purposes are science based rather than creative. This book is essentially about an artist developing their creativity, so it will be considering only the other forms of floral paintings. If you should decide that botanical illustration is for you then there are many excellent books which will guide you.

Second Flush. This painting captures the warmth and glow of an autumnal day, when a second flush of ox-eye daisies dance amongst the red and oranges of the changing colours in the hedgerow. Only the daisies and the veins in the leaves (left) were drawn in pencil first. The daisies were masked before applying paint with loose, fluid, confident marks, taking full advantage of the way watercolour blends and moves on the page. Although an experienced artist can make this look easy, it requires a thorough understanding of both the subject matter and the materials being used.

FIRST STEPS TO CREATIVE FREEDOM

When starting out, there is a need for the beginner to ‘copy’ what they see, a need to make an accurate representation of the flower in front of them; it has to be ‘right’. Watercolour, the usual choice for flower painters, and the medium on which this book focusses, is a challenging medium, and there is a lot to learn about the handling of the paint. Powers of observation too need to be developed. If a beginner were to be placed somewhere on the continuum described above, it would probably be right in the middle, between floral art and botanical art, simply because the level of skill does not allow for the accuracy of botanical art, or the expressiveness of floral art.

As a tutor, it is not unusual for me to come across many people who have been painting flowers for many years, but who are frustrated at not having progressed beyond this stage. A common complaint is that the paintings they are making are too figurative, when they want to paint more loosely. My usual response is ‘Why?’, which often causes a raised eyebrow. The answer usually goes something like ‘Because I ought to be more creative by now’, or even ‘Because I can’t draw; if I paint loosely it won’t matter’. Often, problems are caused by an overenthusiasm to begin a painting with a new, as yet untried, technique, because ‘… Joe Bloggs made it look easy and the effect was stunning!’ In discussion, I discovered they have tried all sorts of things; clearly a lack of motivation to try something new is not the problem.

These comments and complaints are common across the art world, whatever the choice of subject matter. When people start painting, capturing a likeness is often of prime importance. This may be rightly so; there is a typical path that artists follow, beginning with the figurative and gradually, as they become more experienced, moving towards the abstract.

One often hears ‘I want to paint more loosely’ but one rarely hears ‘How do I tighten up my paintings?’. In the world of painting flowers, it translates into a feeling that after starting with attempts at botanical art, progression then involves loosening up to make freer floral art, and then later to be able to paint floral abstracts. However, abstract art is not the epitome of art, the end point for which we should all aim. There are very many beautiful, highly detailed figurative paintings.

If each genre of flower painting is as important as the others, describing progress as a move towards floral abstracts doesn’t make sense. Some people may be happier to move in the other direction, and progress towards botanical illustration. Instead, progression should be described as a deepening understanding of which type of image you want to make, learning the appropriate skill set for that style, and then getting better at it. You may find you prefer to paint in a particular way so that your work settles at one point along the spectrum, falling into a style that suggests it belongs in a particular category. Alternatively, you may decide that you prefer to choose flower by flower, or painting by painting, how you want to make the image; with sound technical skills at your disposal, you have a choice where on the spectrum of flower painting each painting will sit, and you can happily choose whether a painting is to be precise and descriptive, loose and abstract or somewhere in between.

The later chapters in this book take another look at each of the categories of flower painting. There are projects which are intended to give further insight into the reasons behind each of the paintings, including step-by-step demonstrations which you can follow to learn or practise watercolour techniques. In reading the thought process behind each of my paintings, and seeing the effect it has on the design and execution of the paintings in the projects, you may gain insight into your own working method. Simply by beginning to question your intentions for your own paintings, you will be taking a step on the road to greater freedom and creativity in your work. ‘Loosening up’ is not just about how the paint is applied. It can also mean refusing to be beholden to how you think you ought to be painting, and developing confidence in your own purpose and abilities.

Creativity is not undisciplined

The word discipline often rings alarm bells for those wishing to be creative. Creativity is often associated with a splashy, exuberant ‘fling-it-at-the-paper-and-see-what happens’ attitude. Unfortunately, this approach ends in failure and tears far more often than it ends in success. In reality creativity involves proper hard work. When Joe Bloggs made that stunning effect look easy, that was due to a depth of knowledge and understanding borne of experience; they didn’t just get lucky, nor were they born with an extra large helping of magical talent. Of course talent can help, but the rest is down to endeavour and determination.

Discipline in this context is about developing efficient methods of working that enable you to discern how you want to paint, what you want to achieve and to acquire the skills to do those things. It involves learning how to combine an explorative and experimental attitude to your art with a practical analysis of your successes and failures, so that you can build on your experience. It involves time, practice, and lots of concentration. Proper preparation on every level (practical and intellectual) is essential if you want to begin a painting anticipating success rather than failure.

Contrary to expectations, a disciplined approach can lead to greater freedom. A useful analogy is to consider what it is like to learn to drive. When you first sit in the car, you are overwhelmed by the need to co-ordinate pedals, levers and gears, while watching the speedometer, the fuel gauge, reading road signs and, horror of horrors, other motorists. Yet within a short space of time, the handling of the car becomes automatic; you can focus on the journey and safely navigate from A to B.

In this book, I would like to encourage you to acquire a sound grasp of the essential practical tools of producing paintings, and that will require discipline. The tools are:

• Observational skills

• Understanding your materials and equipment

• Design skills

• The thoughtful application of these to implement any ideas you have.

A note on ‘failure’

Very much part of a creative approach to painting is a pragmatic, non-judgemental attitude to the success or failure of each painting. Every painter has paintings that do not turn out the way they had intended, especially if you are painting in a medium like watercolour which has a mind of its own. Learn to think of each one as part of the process of learning to paint. When a painting fails, take a step back and put it into perspective. It is just one painting. Don’t throw it away (yet). Analyze it: what went wrong? What can you learn from it? Do the same when a painting succeeds. Celebrate first, of course, then ask yourself what made it successful.

Draw often! Drawing causes you to see actively rather than passively, and will greatly enhance your observational skills and your visual understanding of the world around you. Draw as often as you can. Making this sketch of an agapanthus in bud forced me to make an accurate observation of the shapes of the buds in various stages of development, and how the angles change as they ripen. Although incomplete (there were more buds) it provides very useful information for future paintings; whether I choose to paint figuratively, or loosely through drawing, I have observed essential features of the essence of an agapanthus.

SEEING LIKE AN ARTIST

If you want to learn to paint, you need to learn to see the way an artist does. Artists genuinely notice more than other people. They are more aware of the play of light, colours and shapes, and more able to spot inspiring subjects.

Without any doubt, the most effective method to learn to see this way is to draw. Drawing does this through active observation. Strangely it is the act of drawing, rather than what appears on the paper, that is most important. It forces you to look much harder at your subject than you would normally. With practice, what appears on the paper improves, providing you with more visual information for your paintings. You learn to look differently, seeing things in a new way; the world itself becomes more visually interesting even when you are not drawing, and you find inspiration in the most unexpected places. Different methods of drawing, and the different ways those drawings are used are discussed in detail in Chapter 5, but why not take a short break now, pick up a pencil and draw something?

There are good reasons to use all the technology available to us, and in Chapter 5 we will be considering how to use photography and other digital media to our advantage. In the community of floral artists, there is some resistance to using photography, which arises because its use to botanical artists is limited, and is not acceptable in botanical illustration because it simply does not provide the right type of information.

Photography is never a substitute for drawing, but it is a worthy tool in its own right. It can be very useful for capturing information quickly, such as fleeting rays of light through leaves, or the position of tulips in a vase before they swing around to the light, entering the window. Photographs themselves can be invaluable inspiration, particularly for abstract paintings.

PLAY TIME

There is substance in the axiom that says there is something beyond the ability to handle materials that leads to success; interest, creativity and talent come readily to mind. But it is also true that no matter how inspired, talented or creative an artist is, unless they can handle the materials success will never come. It could be argued that someone with the desire to paint will automatically take the trouble to learn how to handle the materials, but this does not necessarily follow. Often the end product, the painting, takes precedence over the process of painting it, the latter being seen as simply a means to an end. For example, a student will ask, ‘How do I paint this rose?’ The focus is the rose, and the expectation is that they will be shown one way of painting it.

When the act of painting is undervalued in this way, there is a tendency to neglect developing an understanding of and a familiarity with the materials. The question should be, ‘Which techniques shall I use to paint this rose?’ with an understanding that the painting of it is as enjoyable as the finished piece, and a choice in how to go about it. The process of painting should not be simply a means to an end. Learn to enjoy the medium for its own sake … play with it! Play is a worthwhile occupation in its own right; when you play effectively you learn from it, and discover new and exciting ideas. Chapter 4 sets out guidelines for effective play, one of the most important elements in this creative approach to painting.

Doodle Flowers. This painting was the result of playing with some new paint colours. I began simply by dropping colour onto wet paper, and watching how the colours interacted and moved. Doodling with brushes, I added more layers of paint, and began experimenting with brush marks. I didn’t rush; waiting for effects to develop takes time. Playing with tones and shapes can be a good opportunity to practise balancing a composition. I introduced some lines, which to the imaginative viewer might suggest vases, but was not really important at the time. The purpose was experimentation for the fun of it.

THINK LIKE AN ARTIST

This book describes an approach to painting flowers that is genuinely creative. The approach encourages understanding the fundamental aspects of painting and their importance in designing an image. Along the way it encourages you to have the confidence to make conscious aesthetic decisions, which will lead to a flowering of your own creative style. What this book shares is that the creative process is a considered one, not a magical experience that leaves you hoping for good luck each time you pick up a brush.

There will be demonstrations, exercises, studio tips, and projects for you to undertake, but rather than simply working through them as prescribed activities, you will be encouraged to think like an artist. From inspiration to finished painting, you will be shown how to develop your ideas, working as a creative person works. Yes, it requires discipline, but it also requires a sparkly sense of fun and artistic abandon.

Take another moment to imagine the excitement of finding an inspiring subject that you are passionate about, and that surge of enthusiasm to begin painting immediately.

Take a moment to imagine being able to enjoy the process of painting in that way. It sounds wonderful, so keep it in mind. Let it be your aim, and believe it to be achievable.

Chapter 2

From illustration to invention

It may be surprising, but the best place to start your journey towards greater creativity in painting is at the end.

Promise of Spring. I adore everything about daffodils; they are truly joyful in the way they announce the arrival of spring. In the painting, Promise of Spring, I wanted to capture the feelings of anticipation and hope I feel as the day the first buds open approaches. You have to look closely to spot the buds but once seen, it is difficult not to imagine them fully opened on what is a bright, clear, crisp spring day.

Imagine for a moment a watercolour painting of a vase of flowers, framed and hung on the wall in a gallery. Visitors to the gallery see the painting, and respond to it. They reinterpret the image, their own memories and emotions adding to what is in front of them. They form an opinion; do they like it enough to want to look at it longer? Whatever they are thinking, the point of note here is that they are not responding to the flowers themselves, but to a delightful arrangement of colour, tones and painterly brush marks representing a vase of flowers. This is something different to the vase of flowers itself; it is something new, a ‘thing’ in its own right.

As mentioned in Chapter 1