18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

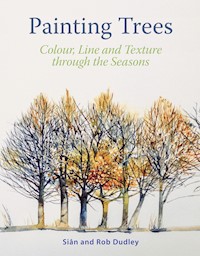

Trees are a magnificent source of inspiration for artists. This book looks more closely at their role in art and how best the artist can capture their essence as the sole subject of a painting, to complete a landscape or to step into an abstract representation. In a unique collaboration, Sian and Rob Dudley combine their skills to offer insights into a range of techniques and styles. There are tips and ideas for finding inspiration, developing your ideas, information gathering, layout, tone and colour within the book. Step-by-step projects demonstrate the techniques in action, from first inspiration through to completion. With practical advice on painting through the seasons to help you to see and paint trees with new appreciation, this book is a joyful and essential guide to creating expressive paintings. A beautiful and essential guide to painting trees creatively with confidence and personal style, it is superbly illustrated with 198 colour illustrations featuring watercolour, oil and pencil technique. Will be of great interest to artists, watercolourists, English countryside enthusiasts, natural history and scientific illustrators, Trees are a magnificent source of inspiration for artists. Sian and Rob Dudley are well-known and respected artists and contribute to the online resource Art Tutor.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 334

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Painting Trees

Painting Trees

Colour, Line and Texturethrough the Seasons

SIÂN AND ROB DUDLEY

First published in 2019 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

This e-book first published in 2019

www.crowood.com

© Siân and Rob Dudley 2019

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 602 9

Frontispiece: Tree Study, Modbury (detail), watercolour, 10cm × 12cm (4in × 4¾in), Rob Dudley.

Dedication

For Huw, for quiet and steadfast supportand for helping us to stay rooted.Thank you.

Youth, Bluebell Wood, watercolour, 23cm × 28cm (9in × 11in), Siân Dudley.

Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1Why paint trees?Chapter 2Materials and techniquesChapter 3Information gatheringChapter 4Designing the paintingChapter 5SpringChapter 6SummerChapter 7AutumnChapter 8WinterFurther information

Index

Introduction

As much as we love painting, and we really do love painting, we also enjoy watching other people delight in realizing that it is perfectly possible to learn how to do it. Achieving success in art is not magic, is not entirely due to innate talent and is rarely due to good luck. The one essential ingredient is having the desire to do it; as long as that is present, we believe that anyone can learn to paint.

Although a little bit of innate talent and an element of luck are undoubtedly helpful, continued success and progression result from the same attitudes that are important in every other part of life: endeavour, commitment and hard work. But do not let this put you off! As long as the desire to be creative is present, the effort that you put in will not seem at all like work.

Orange Tree, watercolour, 22cm × 28cm (8¾in × 11in), Siân Dudley. This sketch was made during a short visit to the Carmen de los Mártires gardens, Granada.

As in other walks of life, when learning something new, it helps to have some sort of structure to guide you. In this book, we have tried to provide just that, by describing our working method. While, as artists, we have our own styles, we have worked and taught together for years and realized that our modi operandi are very similar. Through teaching together, we have developed a method of describing how we work that has enabled many, many students to get started, improve and progress to developing their own styles. Just as a modicum of talent can help, so does a modicum of discipline and, far from restricting creativity, it enhances it, freeing you up to enjoy painting your way, creating the art that you want to make.

Trees are a versatile and fascinating subject matter as a basis for learning how to design and create a painting. Trees provide the most wonderful inspiration for us throughout the year, making crisp, winter sketching trips just as enjoyable as are those on warm, summer days.

The later chapters in this book comprise a series of step-by-step projects, organized according to the seasons. It is not just the quantity and colour of foliage that changes with the seasons, but the very character of trees and the impact this has on the mood of a painting change too. Similarly, the way that the trees are painted, the trees’ placement on the page, the medium chosen and the techniques used to apply the paint have an impact on the way that a viewer responds to a painting. Within the step-by-step projects, you will find plenty of ideas and technical advice about how to make design decisions, so that you can paint trees expressively.

As we describe in Chapter 1, trees appear in paintings for different reasons and, in the step-by-step projects, we have attempted to cover a number of them. In some of these projects, the trees are the main subject of the painting; in others, they appear in the background or as the supporting act for the main subject.

The variety of ways in which trees are painted is so vast that one book simply could not cover it all. This book focuses on painterly, figurative styles, although we hope that the approach taken will encourage you to take this as a starting point and to develop your own way of working. You will be encouraged to think about what interests you and how you want to paint. In time, we hope that you will develop your own figurative way of working, or maybe even find yourself adopting a far more abstract style.

Chapter 1

Why paint trees?

Trees have captured the human imagination since the beginning of time. Through the ages, and in all corners of the globe, trees have played a prominent part in the lives of humans. Our relationship with them may have originated from an intuitive understanding of their significance to our physical well-being, dating back to our ancient ancestors. Trees meet our needs in so many different ways that our relationship with them goes beyond the purely physical, touching us at every level of human experience. It is perhaps not surprising that we feel an emotional bond with them and relate to them more closely than with almost any other plant. It is rare to find a person who does not like trees!

It is unsurprising then, that trees feature abundantly in the arts, inspiring poetry, literature, architecture and of course, painting. It is their place, or maybe their participation, in the latter with which we are concerned in this book.

Teasels and Tree, watercolour, 32cm × 43cm (12½in × 17in), Siân Dudley. This painting was inspired by the way that the glowing autumnal light lit both the hedge behind the tree and the teasels in the foreground. As I was focused on the golden colours below, the uppermost branches of the tree seemed to melt into the bright, blue sky.

Trees are so much part of our lives, so natural a choice of subject matter, that asking the question ‘Why do you want to paint trees?’ may seem superfluous. Yet, giving the question some serious thought might lead to some unexpected ideas and reveal exciting sources of inspiration that might otherwise have been lost in the mists of assumption. Having an awareness of why you want to paint trees will enable you to make informed decisions about how you will depict them in your paintings. As you consider this question, you will begin to discover what it is about trees that you personally find inspiring.

‘Accidental’ Inclusion!

It is very common for someone new to painting to begin by painting landscapes and notice, relatively quickly, that it is quite difficult to avoid trees! Faced with this realization, the novice painter recognizes that they have a challenge on their hands. At this stage, the artist is, appropriately, concerned with figurative representation of their subject matter, and the prospect of having to find ways to represent certain aspects of trees (for example, the character of a wooded hillside or a mass of leaves) can seem quite daunting. Do not be daunted! Throughout this book, there are many suggestions that will help you with these artistic problems.

As an artist gains more experience, techniques are learned and a personal style develops, and the inclusion of trees no longer is something forced upon the artist by the landscape in front of them but rather is something that they will seek out. Trees undeniably enhance a landscape, and being able to paint them convincingly and confidently can lead the artist to a point where the trees play a major role in the composition of the artist’s images.

Home Through the Meadow, 29cm × 45cm (11½in × 17¾in), watercolour, Siân Dudley. In this painting, I wanted to capture the feeling of walking home through a summer meadow. The trees were an unavoidable part of the background to the cottage, but they served the useful purpose of providing darker tones against which to paint the light-toned cottage.

The Visual Beauty of Trees

It may be that, from the very beginning of your artistic journey, trees have been a major source of inspiration for you. Are you able to identify what it is that you find inspiring about them?

It may be tempting to state that you simply find them visually beautiful. This of course is indisputable; we all find trees beautiful, and you are more than entitled to your personal preferences. However, are you able to discern which physical characteristics you find especially appealing? Being able to identify why you find a particular tree or stand of trees visually beautiful will help you to make informed artistic decisions about how you paint the subject matter.

Autumnal Trees, watercolour, 29cm × 25cm (11½in × 9¾in), Siân Dudley. I found the light coming through these young trees, clothed in autumnal foliage, beautiful. That was reason enough to paint this scene.

For example, if what you love about a tree is its overall shape, describing the shape in a simple manner may take precedence over the careful depiction of the shape and distribution the tree’s leaves. Think about images that you may have seen of the cypress trees so typical of Tuscany; paintings tend to focus on the trees’ tall, slender shapes and on their position in the landscape, rather than on detailed descriptions of their leaves.

On the other hand, when we think about an apple tree or cherry tree in full blossom, we think about the flowers and their overall colour. This might inspire a painting that depicts just a few branches rather than the whole tree. Van Gogh took this approach when he painted Almond Blossom.

Contemplate the laciness of branches in winter, the autumnal colour of leaves, the texture of a trunk, the rich, dense foliage in summer and the bright, spring greens of newly opened leaves; all of these, and many, many more features of trees, are excellent starting points for paintings. Take time to ponder over what really excites you, and ask yourself how you can bring these qualities out in a painting.

For us, it is the play of light on and through trees that we both find particularly interesting. Strong sunlight accentuates the contrasts in tone of any subject; when it falls on a bare tree in winter, fascinating things happen. It is not always the outer branches that catch the sunlight but sometimes a branch in the middle of the tree, which gives a sense of intrigue due to its unexpectedness. At the same time, the tonal range from highlights on branches to the deep, dark shadows that the branches cast gives a real sense of the depth and shape, and it highlights textures of the bark. Similarly, in summer, a patch of sunlight may slip through an area of foliage, causing a group of leaves to positively glow against the rich, dark greens of an area more densely populated with leaves.

The Big Beech Tree: Winter (detail). The play of light amongst the branches, accentuating the branches’ twisting shapes, inspired the making of this graphite image. The full image can be seen in Chapter 8.

This book is about trees as the inspiration for painting. While we have a genuine interest in trees, and each of us has a favourite species, being able to identify a tree by name, or describe its growth pattern in botanical terms, is of little importance compared with the visual pleasure that the tree provides. Any information about the tree is interesting when developing your ideas of painting it, but care should be taken not to become embroiled in allowing what you know about the physicality of the tree to overly influence your design for your painting.

Focus your attention on what excites you about the tree that you see before you. This will free yourself up to create beautiful expressive paintings, rather than you expending any of your creative energy on things you may have learned from reading about the tree.

The Intangible Qualities of Trees

There are other aspects of trees that might inspire an artist to paint them or to include them in a painting. These qualities are more subjective, intangible qualities.

We describe trees as having strength, grandeur and elegance. We may say that they are ethereal or sinister. Many of the characteristics that we attribute to them could also be applied to ourselves, although, at this level, we are not anthropomorphizing trees but recognizing something about them with which we connect at a deep level. Our use of this type of language recognizes our emotional response to trees, and it is so ensconced in our daily language that we do this subconsciously.

As an artist, it might be useful to take some time to consider this aspect of trees and how it relates to the paintings that you make. Is this something that is important to you, in that recognizing your emotional response to trees is at the root of your inspiration? Or might it influence your work in another way, for example, in considering how your choice of tree might affect the narrative of a painting? If your intent in making the painting is to evoke a particular emotional response in the viewer, having an awareness of your own response to trees would be very useful.

To put some of this into context, consider the oak. The oak is considered to have the qualities of strength and endurance (its size and longevity obviously being the basis for this). It is often described as noble or majestic. It has a presence, an aura, that implies a history.

Imagine a painting of rural England, with a farm field taking centre stage. Placing an oak in the centre of the field immediately adds an element of history to the scene and, hence, depth to the narrative. If the oak is removed, or replaced with a different species, for example, a single apple tree, the painting acquires an entirely different feel and loses its sense of history.

Gainsborough used his understanding of this concept when he painted Mr & Mrs Andrews (c.1750). The featured couple sit under an oak tree, which was intended by Gainsborough to deliberately reflect Englishness, stability, continuity and a sense of successive generations managing the family estates.

TREES AND SYMBOLISM

Through the ages, trees have acquired symbolic meanings. These differ from culture to culture and between different mythologies and religions. Here are just a few…

Aspen: exploring, and spreading your wings

Birch: new beginnings

Cedar: healing, cleansing

Cherry (tree): love, romance and, when in flower, good fortune

Elm (old-growth): intuition, strength

Maple: balance, promise

Oak: stateliness, power and courage

Olive (branch): reconciliation

Palm: peace

Redwood: forever

Wisteria: romance

A Sense of Place

Trees stand tall, solid and strong, rooted in the earth. Unless moved by humans, they remain in that place where each tree’s originating seed germinated, for their entire lives. They become an integral part of the place in which they live, contributing visually to the landscape and biologically to the local ecosystem. Since different species grow in different climates, it is easy to see how, on a global scale, trees can impart a sense of place.

At home in Devon, England, we are used to seeing hawthorn hedges, which are intended to keep farm animals enclosed within fields; these hedges are often wind pruned, indicating the direction of the prevailing wind. Many of the local farm fields have a large oak standing proud in their centre, under which cows and sheep shelter from the sun. Although relatively unfamiliar crops have invaded the landscape in recent years, the trees still tell us that we are at home in England. When on holiday in southern Spain, the local trees were olives and almonds, the surprising blackness of their trunks making a real and lasting impression on us of an unfamiliar landscape, which will forever remind us of the Alpujarras.

In paintings, trees can be used very effectively to convey a sense of place, simply by the artist’s choice of species that are appropriate for a particular area. Close observation of how trees grow in a particular area will help you to describe that area. Conversely, a sense of mystery could be imparted to a painting by your deliberate choice of inclusion of an inappropriate species.

A single tree can also impart a strong sense of place. We become familiar with individual trees in the local area. Near our home is a wind-pruned hawthorn tree shaped just like a teapot; we call it The Teapot Tree. Another local tree, split by lightening, has earned the nickname The Tuning-Fork Tree. It is probable that every town, village and hamlet in the country has at least one tree known to all of the local residents, complete with nickname!

Single trees can make wonderful subject matter for artists. A popular project is to paint a particular tree throughout all of the seasons. The obvious thought here is to study a deciduous tree, which will have brilliant, bright, fresh growth in the spring, abundant summer foliage, rich autumn colour and open, lacy patterns in the branches in the winter. We have taken this approach with The Big Beech Tree, which we visit regularly, as we find it so inspirational. The paintings that we produce are intended not as a simple record of how the tree changes each time that we visit it but rather as a record of our response to it when we are in its vicinity. As a result, the paintings are varied in both style and the media that we chose to use for each painting. One of four different The Big Beech Tree paintings can be seen at the beginning of each of Chapters 5 to 8.

With just a few brushstrokes, this quick watercolour sketch captured the character of each tree that is so typical of the Alpujarras, Spain.

However, evergreen trees can also make marvellous subjects for such a project; since the changes in the tree are relatively small compared with those of a deciduous tree, the variations come from changes in light, weather and atmospheric conditions, and an evergreen tree can be every bit as inspiring as a deciduous tree. Other seasonal changes are recorded around the tree, and, as the project takes some time to complete, the artist will develop an affinity with the place too. The differences in the paintings made as the project progresses may be subtle, perhaps through more-confident mark-making or minor adjustments to the composition. All of this will add to the artist’s sense of place and help to convey this to the viewer, so that they too feel the connection.

Environmental Advocacy Through Art

The obvious stature of trees in their environment belies the degree to which they are a part of a community of organisms. Underground, they are supported by mycorrhizal fungi, which help to bring water and nutrients close to the trees’ roots. Above ground, there are a myriad of microcosms upon their trunks and within their branches, supporting all manner of life! Birds, fungi, mosses, frogs, mistletoe and ferns, and even other trees, can be seen growing amongst their branches. In addition to looking at how trees can help us to understand our geographical place on the planet, we have much to learn from trees about our place in the ecosystem.

In an era where science can often overshadow art, it is easy to focus on the ways in which trees can be of enormous benefit to both the planet and us as a species. The part trees play in maintaining the temperature of the planet is well-documented and reported frequently in the press, so that even those with little interest in global warming or science can hardly avoid gaining an understanding of the significance of trees. Many studies have been conducted on the ecosystem benefits provided by trees. Trees absorb carbon dioxide, release oxygen into the atmosphere, increase the stability of land and thus reduce erosion, cool water to a suitable temperature to support native fish, and much, much more.

Wanting to get the message across to those who have not yet heard it is inspiration enough for many artists! Art has, and has always had, the ability to reach those who are impervious to messages delivered by other means. TV and radio programmes end and are forgotten; a piece of artwork remains in place, always visible. Even for the viewers whose gazes are transient, the art sits there, subliminally entering their consciousnesses through the corners of their eyes.

Environmental advocacy is an excellent reason for painting images of trees! The message can be very deliberate, overtly causing the viewer to question, such as one might find in a surreal image of a dystopian future. But the message need not be so obvious. Beautiful images of trees can be enough to inspire the viewer to think about the planet. Painting something that inspires you may be enough to inspire your views to go out into the environment and make a similar connection with the viewer. Of course, if you can design an image with a narrative somewhere between these two extremes, you could successfully encourage people to take more action too.

Art has always been used to express messages and is perfectly valid as a reason for painting trees!

TREES

Joyce Kilmer

I think that I shall never seeA poem lovely as a tree.

A tree whose hungry mouth is prestAgainst the earth’s sweet flowing breast;

A tree that looks at God all day,And lifts her leafy arms to pray;

A tree that may in Summer wearA nest of robins in her hair;

Upon whose bosom snow has lain;Who intimately lives with rain.

Poems are made by fools like me,But only God can make a tree.

Joyce Kilmer makes his feelings about the beauty of trees quite clear in this short poem, ‘Trees’ (Kilmer, J., Trees and Other Poems [Doubleday Doran and Co., 1914]). While we cannot disagree with him on the beauty of trees, there is a feeling that he has slightly missed the point about art. Poems and paintings are not trees; they are about trees and can be beautiful in themselves. Artists are not making trees; they are making paintings – new entities in their own right. You will not be hanging a tree on your living-room wall but a painted image of one. And that can be a beautiful thing!

Trees and Health

Humans have always instinctively understood the value of trees to their own physical and mental health. The physical benefits are obvious. Trees provide shelter, oxygen, food, building materials, paper and so on. Medications can be made from various parts of a tree, including leaves, bark and roots.

Intuitively, we know we feel more relaxed and are more mentally alert if we spend time in natural surroundings. In an era where we are becoming increasingly urbanized, a number of studies have considered the link between trees and mental health. It is now well-documented that a short break during the working day that is spent outside amongst nature increases a person’s ability to focus on their work, increases job satisfaction and reduces employee illness. Humans have a strong preference for landscapes with trees or woods; studies have shown that, in areas with more trees, house prices are higher, commercial regions attract more customers and employment rates are higher.

An artist has a huge advantage here! Since the time spent making a painting involves preparation in the form of information gathering, it is absolutely essential to spend time outdoors walking, looking, sketching and photographing. If the painting is completed en plein air, so much the better. Use your art to encourage others to do the same: organize sketching trips or paint images of places that people want to visit.

Painting trees has to be good for your heath!

Lunch with Robin, watercolour, 37cm × 26cm (14½in × 10¼in), Siân Dudley. A short lunchtime walk amongst nature can be both refreshing and inspiring. After a tedious morning, just such a walk inspired the making of this cheerful watercolour painting.

PAINTING TREES: THE PRACTICALITIES

When it comes to how trees are portrayed in art, our emotional response to trees transcends our scientific understanding of our symbiotic relationship with them. Just as they are a staple part of our existence, they are a staple part of our artistic endeavours. It is no wonder that they have been the subject for painters for hundreds of years, either as elements within a painting or as the main subject of the artwork itself. The representation of trees in art can be as varied as the different trees themselves, transcending all styles and movements, from photorealist pixel-perfect representations to the often simplified colours, shapes and forms of abstract works.

Trees have been the inspiration, the focus, the background of countless artworks. They have been used as compositional devices, represented allegorical elements within narrative paintings, been pared down to abstracted simplicity or been examined in minute detail. The humble tree has done it all.

Considering two artists working with trees as their subject matter, compare the different interpretations by the English painter John Constable (1776–1837) with those of the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian (1872–1944). Constable’s approach is very naturalistic, and his deft brushwork depicts the wind-lifted leaves along the banks of the River Stour. Mondrian’s far more abstract approach interprets leaves as geometric, interlocking, branch-like shapes. Using the same starting point, trees, both painters producing captivating, yet very different, images.

Glowing Teasels, watercolour, 23cm × 32cm (9in × 12½in), Rob Dudley. In this image, the trees are purely background. The viewer’s eye is drawn first to the teasels and then to the grasses, the cottage and the sky. Finally, the viewer may notice the trees. Despite their seeming irrelevance to the subject matter, the trees perform an important role, in providing dark tones that highlight the glow on the teasels and in the sky, that frame the cottage and that act as stoppers, preventing the viewer’s eye from leaving the scene and instead guiding it back to the teasels.

Painting Trees in the Landscape

One of the most popular painting genres found around the world is that of landscape painting. Within landscape painting itself there are numerous subgenres: towering snow-capped mountains, wide, expansive moorlands, flower-filled meadows and reed-filled marshlands. Whichever type of landscape is being portrayed in a painting, it is undeniable that trees play a prominent part. Indeed, for many a landscape painter, it is trees and the painting of them that fills their work. They are a staple of our lives; they are also a staple of our paintings. We cannot do without them.

Slapton Ley, watercolour, 30cm × 30cm (11¾in × 11¾in), Siân Dudley. The trees (and the reeds) in the foreground of this painting are intended to attract attention, drawing the viewer’s eye into the image, but they are not the focal point. The trees are designed, in particular by using specific shapes and tones, to lead the viewer’s eye through them to the light on the water beyond. Once the viewer’s eye arrives there, the trees recede in the viewer’s mind, as they are subconsciously considered as being something to look through rather than at.

For generations trees have been the subject of, and are the indispensable elements within, landscape paintings and, for as long as trees grow on the planet, they are likely to be for generations to come. They might form only a small part of the artwork, but they can still have a dramatic impact on the overall mood or atmosphere of the painting. The colour of the foliage, or lack of it, can describe the season. Shadows within or cast from trees can suggest the time of day or even indicate the warmth of the day by implying the strength of the sunlight.

The careful inclusion of well-placed trees can add to the sense of space and distance within the artwork. Trees can feature in the landscape in ones or twos or as vast woods and forests. In short, they are an essential component of the landscape-painter’s art.

Untitled, watercolour, 50cm × 26cm (19¾in × 10¼in), Siân Dudley. This stand of trees was enchanting and needed no background or context within a painting. As the sun played on the bare branches, the trees’ tips glowed, and the shadows deepened. Both of these effects were enhanced in the painting by the choice of complementary colours and exaggeration of the tones.

Within landscape paintings, trees can play different roles. They can be part of the background, be part of the supporting cast or be the focus of the painting. They can be used more overtly as compositional devices, playing a far more obvious role. They can be used as part of the narrative, having an essential role in the image.

Trees as a Background

Trees can be used as the background or as a backdrop to the action taking place in front of them. Used in this way, they are subtle compositional devices, used by the artist to lead the viewer’s eye towards the main subject matter of the painting. They are painted in such a way that the viewer almost overlooks them, maybe coming back to reconsider them only after thoroughly examining the rest of the painting. Without wishing to imply a lack of importance to the overall image, in this sense, the trees are sometimes little more than fillers. If this is what you have intended from the start, this is no bad thing; it requires a degree of skill to paint the trees so convincingly that they perform this role!

Used in this manner, trees can be extremely useful. The tone and colour of these trees can be used to bring the focal point into sharp focus by, for example, ensuring that these trees are dark in tone if the focal point is light. They can be coloured to lead the viewer’s eye around the painting, directing the viewer to the area that you wish their eye to rest on. Trees performing this role within a painting are usually en masse, such as you might see in a wooded hillside, a small copse or a hedge.

Trees as a Compositional Device

When designing a painting, it is not uncommon to rearrange, alter or even invent some of the elements that come together to make a successful painting. Moving a building here and adding a cloud there all add to making a stronger whole. Using trees in this way means placing them deliberately within an image, just where they are needed. For example, trees can be added to hillsides to balance compositional designs or be removed altogether, if it strengthens the overall image.

Used in this manner, the trees will claim some of the attention. They are a more obvious part of the composition than trees used as a background. Depending on how they are used, they may even be a part of the focal point, though not being the main subject matter of the painting.

The key, particularly when adding trees to the design, is to ensure that they look as if they could grow where they are positioned. Size, detail, texture, tone and colour must all be assessed correctly in relation to the rest of the painting, otherwise the arboreal addition will stand out like a sore thumb and likely unbalance the rest of the design.

Trees as the Subject

Trees are very beautiful and deserve to be the subject matter of paintings, where the artist invites you to examine the tree, or aspects of it, for what it is. These paintings can be pure, simple, descriptive and direct. Our love of trees is such that we can gaze at such paintings for hours, following the lines of the branches or enjoying the colour of the leaves, much as we would watch flames flickering in a fire.

Very descriptive, figurative paintings, verging on the diagrammatic, can be enjoyable and interesting. But trees inspire emotions, and the artist can evoke an emotional response to a painting of a single specimen, by carefully choosing the style in which it is painted. A tight, or detailed, descriptive rendition of the bark might evoke memories of the texture, while a loosely painted image might be more ethereal, evoking memories of long, summer days or of misty mornings.

Close inspection of trees can reveal whole new sets of subjects for the observant artist to consider. Deep fissures in the textured bark to the shapes, colours and patterns of leaves can all be starting points for exciting tree-based projects.

AN APPROACH TO PAINTING

Throughout this book, there will be plenty of practical advice on how to design paintings and to implement this advice to actually make a painting. Knowing why you are painting the image will help you to decide on your approach and which techniques to use.

The techniques demonstrated in this book are those used for the featured paintings or for the step-by-step projects in later chapters. There are many more techniques available to an artist than it is possible to include in one book! It is important to remember that our intention is not that you just learn how to paint each of the images provided in the later chapters but is that you absorb and develop the approach to painting. This allows you to extrapolate from the lessons in this book, to identify your own purposes for each painting that you make and to find the appropriate techniques to use; whether you discover those techniques through this book or by the attitude of experimentation that it promotes. Our intention is that you use this book as a springboard for your own work.

Choice of Media

This book features mainly watercolour, oil and pencil artwork. Painters using these media will find lots of techniques specific to these media.

However, much of the advice given applies across all media. All of the tips and techniques given for finding inspiration, developing your ideas, information gathering, layout, tone and colour are cross-media. SeeChapter 2, Materials and Techniques, for ways to explore different media and apply them effectively to the realization of your ideas.

Trees Near Soar, water-mixable oils, 30cm × 20cm (11¾in × 8in), Rob Dudley. The wind had bent these trees into such an interesting shape and, with the low sun casting such long shadows from them, they just had to be painted!

Chapter 2

Materials and techniques

Most books of this type have a chapter on materials and equipment, providing extremely useful hints and tips on what to use and how to use it to create beautiful works of art. This book is no exception. What follows in this chapter are many hints, tips and descriptions of techniques that can be used to create beautiful paintings. But, with all the best will in the world, this chapter will not be able to give you the vital ingredient that will enhance your painting.

The vital ingredient is you.

Experimenting with mark-making, Siân Dudley. In the initial stages, a watercolour painting went wrong. Having washed off the first washes and repeated them twice, I gave up. Rather than throw the failed painting away, I used it to give context to experiments with some water-based ink pens, experimenting with mark-making and observing how the two media worked together. This sheet will be kept for reference.

This chapter is not really about the art materials, equipment and techniques. This chapter is about you.

The vital piece of information that is often, perhaps strangely, overlooked is that the materials themselves are nothing without the hand that holds them. Art materials are inanimate. Left to their own devices, they will sit obediently wherever you left them, gathering dust rather than miraculously making paintings of their own accord. When you watch another artist painting, it is clearly important to take note of the tools that they are using, but never forget that it is not the tool that makes the mark, it is the artist’s hand.

And, when it comes to making your own paintings, that hand is yours. No amount of watching or reading will enable you to make a painting. That will happen only when you pick up your materials and start using them. It follows that the best advice that you could receive would be to pick up those materials and try them out!

INVESTIGATING MATERIALS

In practice, the very best way to learn to paint is to pick up your materials and play with them. Children learn through play, but as adults we forget its value. In the context intended here, play means giving yourself permission to let go of the need to produce a painting. Instead, spend some time investigating what you are able to do with the materials that you have. There is an old adage that says that time in reconnaissance is never wasted; devoting time to simply playing with art materials will not only give you skills in handling them but enthuse you and inspire greater creativity. Adopting this approach can be as useful and inspiring for those with a little more experience as it is for beginners. Free yourself from the pressure of producing a great work of art, relax and relearn the art of experimental investigation. Play!

PROJECT

Learning through play

Time spent learning to use your materials is invaluable! It should never be underestimated.

Take time to get to understand how your materials work. How do your brushes respond to your hand movements? How do your paints respond to your supports? Are you easily able to find the exact colour or tone that you need?

Make time to experiment with your materials. Ask yourself these questions:

1 What can I do with…?

For example, what can you do with your brushes? Spend time playing with them, each in turn, to discover the different types of marks and effects that you can create with each one. Work on dry paper, wet paper, rough surfaces and smooth surfaces, change the angle of your hand and hold the handle in a different place. Try loading the brush fully and using it almost dry.

2 What will happen if…?

For example, try discarding the brush and picking up something else, anything, with which you think you could make a mark. Sticks, toothpicks, palette knives, feathers, string…

What happens if you use the ‘wrong’ hand, your non-dominant hand? What happens if you close your eyes and flick paint at the painting surface?

3 How did that happen?

Watch carefully what happens as you play. Remember to keep watching as the paint dries (over several days, if necessary).

Use any ‘happy accidents’ that occur as learning experiences. They need not be one-offs. Such an accident was happy because you liked the effect, so try to work out how it happened and then practise making it happen on purpose; with just a little practice, you will be able to do this.

Experiment with mark making, play with your brushes, whatever the medium being used. Try to make as many different marks as you can with each of your brushes, for it is these marks that can lead to the creation of better paintings.

THE VARIETY OF MEDIA