20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

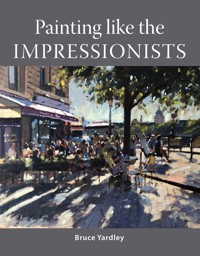

Impressionism, an art movement pioneered by a handful of avant-garde painters based in Paris in the 1870s, gave academic oil painting a vivacity and spontaneity it had previously lacked, and remains to this day the single most popular style of art for gallery-goers and amateur painters alike. This elegantly-written book, by a professional artist and scholar, is both an instructional guide to incorporating Impressionist techniques into your own painting, and an illuminating investigation into how those first Impressionists actually painted their pictures. As such, it will fascinate both the painter and the art historian. This new book provides detailed advice on paints, brushes and canvas, as used by the original Impressionists and still widely available today. It discusses the process of making an Impressionist painting from initial vision to final completion and analyses the role of composition, light and tone, colour and paint handling. Finally, it gives an overview of the subject matter most closely associated with the Impressionists.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 330

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Painting likethe Impressionists

Painting likethe Impressionists

Bruce Yardley

First published in 2021 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

This e-book first published in 2021

© Bruce Yardley 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 911 2

Cover design: Peggy & Co. DesignFrontispiece:Peonies and Work Table, oil on canvas, 41cm x 30cm

Contents

Preface

In writing this book I’ve tried to picture a reader who has been working in oils recreationally for some time, and who wishes their paintings to acquire something of the expressiveness they see in Impressionist art, the style of painting first brought to public attention by a small group of French artists in the third quarter of the nineteenth century. But I’ve also had in mind a wider audience, one that simply wishes to know more about how the Impressionists actually made their pictures. For it struck me, while doing the research for this book, how rare it is for conventional art historians to address this question head-on. Whatever practical information they do provide is often buried beneath a welter of less practical criticism.

I therefore discuss the Impressionists’ working practices as well as my own, at least in the main text. As a result, readers might expect to see more illustrations of Impressionist paintings, which are here confined to the pages of the Introduction. In response, I’d say two things. First, the cost of including more of these pictures would have made this book prohibitively expensive; with a couple of shining exceptions, custodians of Impressionist works are not very generous in their image-sharing arrangements. Secondly, the most efficient way of consulting an Impressionist picture is to look it up online. All of these paintings are now out of copyright and in the public domain: anyone with a computer or tablet to hand can call up the relevant image in quicker time than it would take to flick through the pages of the book in which it is mentioned.

My book was put under contract in late 2019 and I began work on it at the start of 2020. The Introduction and most of Chapter 1 were written by the time that the UK went into lockdown over the Covid pandemic. This put me in a quandary. Should I refer to these events in the book, knowing that they were disrupting our painting lives? For one thing, the opening paragraph of the Introduction, in which I suggest that museums and public collections might solve their financial difficulties by putting on Impressionist-themed exhibitions, no longer held true. In the end, though, I decided to make no adjustment to what I had already written and to carry on as though nothing had happened, even at the risk of sounding out of date. Who knows what the world will look like when this book is published; the impulse to paint will never leave us.

Bruce Yardley

Bath, October 2020

St Paul’s: Summer Morning, oil on canvas, 122cm × 102cm

INTRODUCTION

The Appeal of Impressionism

The board of a civic art gallery or museum struggling for funds would be well advised to put on an exhibition of Impressionist painting, for the public appetite for such shows – inevitably labelled ‘blockbusters’ – appears insatiable. If the resulting show can include the name Claude Monet, so much the better. Why has the wider public taken this form of painting, above all others, to their hearts?

Mixed Flowers in the Window, oil on canvas, 76cm × 51cm

There are, I think, a number of reasons. The vigorous brushwork and elimination of detail that you see in a typical Impressionist painting give it an immediacy and impact that more carefully wrought artworks often seem to lack. As a result, for me and for others, these pictures offer the most satisfying balance between representation and abstraction, with not too much and not too little left to the imagination. Next, the wide-ranging subject matter, presented without any predisposition to flatter, moralize or edify, is for most of us nearly always more congenial than the homilies in paint one so often sees in the pre-Impressionist era, and the mysteries in paint one so often sees in the post-Impressionist era. Finally, and perhaps crucially, the Impressionists’ ability to suggest and summarize with a few deft dabs of paint invests the act of painting with an alluring simplicity. As Neil MacGregor wrote, when introducing an exhibition of Impressionist paintings at the National Gallery in the 1990s, ‘There is the heady illusion that we could almost have painted these pictures ourselves.’

Before I expand upon these opening remarks I should explain that I am really referring to the first flush of Impressionism, the period dating from the late 1860s through to the early 1880s. The later works of the main protagonists, while still labelled Impressionist in most art books, only rarely provide a working model for the kind of painting I am advocating here. Even Monet, who is justifiably called the ‘quintessential’ Impressionist, had by the mid 1880s abandoned the ‘quick impression’ in favour of a much more laborious style, in which a densely worked paint surface is assembled over very many sittings (he was known to complain about how long these paintings took him). The huge, rhythmic waterlily compositions he undertook in the last thirty years of his life are different again, and have more in common with Expressionism than with Impressionism. Camille Pissarro was similarly mercurial, turning the interest in broken colour that he shared with other Impressionists into a pointillist obsession: the resulting works are demonstrations of colour theory that have little to do with Impressionism as I understand the term.

Claude Monet, The Zuiderkerk, Amsterdam, 1874, oil on canvas, 55cm × 65cm

Monet’s canvases became much more laboriously worked after the mid 1870s, when the number of sittings he required to complete his paintings spread over days, weeks and even months. This painting just predates that period, and we can perhaps see the beginnings of his later manner in the dense broken colour of the canal water.

(Courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art. Purchased with the W.P. Wilstach Fund)

On the other hand, the principles that underpinned the pure Impressionism of the 1870s were quickly taken up elsewhere, so for every lapsed Impressionist there is a credible alternative whose paintings do provide a good working model for the kind of painting I am advocating. I am thinking here particularly of the Englishman Walter Sickert and the American (resident in London) James Abbott Whistler, two painters who are cited frequently throughout this book. Sickert in his younger days was a disciple of Degas, and although his painting methods owed little to Impressionist precept, inasmuch as he disdained painting out of doors (‘Never paint from nature’, he told his students), the pictures themselves were imbued with the spirit of Impressionism. The same is true of Whistler’s works, especially his spare, atmospheric crepuscules and nocturnes.

Sickert and Whistler were both instrumental in introducing French Impressionism to the English art establishment, who were initially resistant to its charms. By the end of the nineteenth century, however, England was developing its own native brand of Impressionism, one decidedly less colourful and more tonal than that of the French. And it is in the context of English Impressionism that I must mention a further painter, one still active today, whose work has been a big inspiration to me: Ken Howard. His subject matter is very wide and his influences are not obvious, though Monet, Sickert and Eugène Boudin, the proto-Impressionist who specialized in small-scale beach scenes, all come to mind at different times when viewing his oeuvre. The point is, there now exists a rich and varied Impressionist tradition, and all of us who operate within it today might take our lead from any number of different painters from the last 150 years.

Eugène Boudin, View of Trouville, 1873, oil on panel, 32cm × 58cm

Boudin was a proto-Impressionist, inasmuch as he introduced the young Monet to the pleasures of plein air painting in his native Normandy, and continued to exert an influence over Monet and Monet’s student colleagues Renoir and Sisley. Many of Boudin’s landscapes were effectively cloudscapes, for which he had a real facility – Corot called him ‘King of the Skies’.

(Courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art. John G. Johnson Collection)

Claude Monet, Railway Bridge, Argenteuil, 1873, oil on canvas, 54cm × 73cm

Rail travel helped free the artist from the studio, so I find it somehow fitting that railways feature in some way or other in so many Impressionist paintings. This is Monet’s depiction of a railway bridge near his then hometown of Argenteuil; the colours of the sunlit engine steam are duplicated in the bridge pillars and the various river reflections.

(Courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art. John G. Johnson Collection)

The original French Impressionists were reacting against the art traditions in which they had been schooled. Each of them was academically trained, with the sole exception of Berthe Morisot, who nevertheless received instruction from several professional painters, including the celebrated Barbizon artist Camille Corot (women were not allowed to enrol at the École des Beaux-Arts until 1897). The quartet of Monet, Renoir, Sisley and Bazille attended the same atelier, and by the end of the 1860s all the key participants in what were to be the ‘Impressionist’ exhibitions of the 1870s and 1880s already knew each other well. Their collective self-promotion was intended, in the first instance, to create an alternative marketplace to that of the Salon, the annual exhibition closely regulated by the École des Beaux-Arts where young painters would hope to find patrons, and the kind of art promoted by the renegades was quite different from that sanctioned by the École.

Alfred Sisley, Flood at Port-Marly, 1872, oil on canvas, 46cm × 61cm

Sisley is less well known than his fellow students Monet and Renoir, but he never suffers in the comparison when they shared subject matter. Sisley and Monet sometimes painted together in the late 1860s and early 1870s, and their paintings are easily confused. This low-horizoned, gentle painting has a warm glow, due in large part to the happy combination of the orange of the building’s lowest storey, and the pale green-blue of the floodwater.

(Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington. Collection of Mr and Mrs Paul Mellon)

The best way to appreciate that difference is to take a chronological stroll through the nineteenth-century rooms of any major public art gallery. In the mid-century rooms you will encounter intricately designed, highly romanticized interpretations of historical or mythological narratives, executed in sombre colours with theatrical lighting effects and a detailed, superfine finish. Enter the rooms given over to Impressionism, however, and you will encounter the exact opposite – spontaneous, unsentimental, boldly coloured and wilfully under-finished observations of ordinary life as lived at the time. It’s easy to see why the names of Monet, Renoir et al are well known today, while those of the Salon favourites such as William-Adolphe Bouguereau, and their Royal Academy counterparts across the Channel, are not. To the modern eye there is something artificial and even hypocritical about those polished and pious Academy-approved canvases; the Impressionist works, with their unaffected celebration of the everyday, seem honest and reliable in comparison.

Auguste Renoir, The Grands Boulevards, 1875, oil on canvas, 52cm × 63cm

Renoir’s brushwork was always distinctive – ‘he paints with balls of wool’, said the acerbic Degas – and the general view is that it was better suited to soft, sensual portraiture than to the unromanticized landscape of Impressionist preference. Here, though, the strong composition and relatively restricted palette give the painting a solidity that Renoir’s work sometimes lacks.

(Courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art. The Henry P. McIlhenny Collection in memory of Frances P. McIlhenny)

Berthe Morisot, Peonies, c 1869, oil on canvas, 41cm × 33cm

As the only woman among the original Impressionists, and perforce as the only artist not to have received formal training (women could not enrol at the École des Beaux-Arts until the 1890s), Morisot was condescended to throughout her career. Yet her brushwork and paint-handling were as vigorous and original as any. This small, quite early picture of peonies, a favourite flower subject among the Impressionists, displays two of her traits – the warm grey background, scrubbed on in such a way as to allow the under-tint to shine through, and the idiosyncratic zig-zag brushwork at the bottom.

(Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington. Collection of Mr and Mrs Paul Mellon)

Claude Monet, Rouen Cathedral, West Façade, Sunlight, 1894, oil on canvas, 100cm × 66cm

By the time Monet came to paint his Rouen Cathedral sequence, working from a cramped milliner’s shop opposite, he had evolved a painting style that created a very dense paint surface, achieved by working on a large number of canvases at the same time over a long period. The pictures were thus very different from the ‘quick impressions’ he had produced as a young man. In this canvas the sun seems to be melting the surface decoration of the Gothic building.

(Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington. Chester Dale Collection)

That unaffected celebration of the everyday took many forms. It might be a jovial, well-dressed party of young professionals enjoying a dinner-dance, or a solitary, care-worn derelict nursing a drink in a bar. It might be a gang of labourers mending the flagstones of a boulevard, or that same boulevard bedecked with flags on a public holiday. It might be a cathedral of God or a cathedral of the railway. The weather might be sunny, cloudy, or rainy; there might be snow or fog or floods, or gusts of wind. Refusing to accept the long-held belief that some subjects were more worthy than others of the artist’s attention, the Impressionists put on a pictorial variety show, the different exhibits united by a sense of light and movement captured in paint.

Edgar Degas, After the Bath, Woman Drying Herself, c 1896, oil on canvas, 90cm × 117cm

Degas had a semi-detached relationship to the younger members of the Impressionist group; he participated in all but one of the group shows but his working methods were quite different from theirs, relying as he did on a careful assemblage of studio drawings before undertaking the actual painting. He’s best known for his informal portraits of ballet dancers and women at their toilette; this large canvas is a late, hot-coloured example of the latter.

(Courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art. Purchased with the funds from the estate of George D Widener, 1980)

Claude Monet, The Houses of Parliament, Sunset, 1903, oil on canvas, 81cm × 93cm

Monet made three painting trips to London in successive years from 1899–1901, finishing many of the resulting paintings in his studio on his return to Giverny, as the date here demonstrates. He particularly liked the fog and smoke that settled over the Thames, and in consequence there is a soft, ethereal quality to these later works. The younger Monet, the Monet who first came to London in 1870, would have painted these buildings with greater definition and solidity of colour.

(Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington. Chester Dale Collection)

Claude Monet, Palazzo da Mula, 1908, oil on canvas, 61cm × 81cm

Monet’s much-anticipated trip to Venice in the autumn of 1908 was his last major painting excursion; widowed once more, he bunkered down in his Giverny water garden, painting the enormous, mural-like canvases that were to dominate his last years. The viridian-and-violet pulse of this Venetian painting shows how far he had departed from his more literal palette of the 1860s and 1870s. Is it in fact a symptom of the cataracts that were increasingly to plague him?

(Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington. Chester Dale Collection)

All of this is brought into sharper relief when you wander into some of the other rooms in that hypothetical gallery I referred to above. The medieval and Renaissance rooms will probably yield a high count of gurning faces and writhing limbs belonging to saints and sinners caught in the throes of religious agony or ecstasy. The seventeenth-and eighteenth-century rooms will almost certainly parade the alternately smug and stern countenances of the rich and powerful of the temporal world, sharing wall space with land battles and sea battles and menageries of freshly killed wild animals posed unappetizingly upon the dining table. As for the twentieth-century rooms, they can be relied upon to plot the course of a growing introspection, in which the mental and emotional health of the artist is allowed to assume the role of the subject itself. I don’t mean to denigrate non-Impressionist art with these reductive caricatures. Outstanding paintings have been produced in every era. But it’s hard to deny that for many of us there is more comfort and joy to be had from the paintings of the Impressionist era than from those of other eras. Indeed, for unapologetic fans like me, the dozen-odd years during which French Impressionism first came to public notice represent the extended moment when painting was at its most humane.

Those years also represent the extended moment when art acquired a new painterly language without sacrificing its ability to communicate a recognizable and believable image of the visual world. With a few notable exceptions such as Velázquez, Frans Hals and Rembrandt, earlier artists rarely allowed the actual paint surface to feature prominently in the finished work: the paint was smoothed and modelled as if to divert attention away from the medium. The Impressionists were far more willing to let us see their pictures for what, in essence, they were: agglomerations of different marks of pigment. A typical Impressionist painting gives us a strong sense of the artist’s pleasure – and occasionally frustration – in the act of putting paint to canvas. The result is artwork with vastly more textural interest than what went before.

The Impressionists’ vibrant palette was another expression of this painterly quality. Informed by the latest thinking in colour theory, they strove to suggest light and form by means of firmly differentiated, juxtaposed brushstrokes of paint. Seurat, Pissarro and others developed this ‘broken colour’ into pointillism, covering the canvas with a mosaic of differently coloured dots – too methodical a technique to be truly impressionistic, but the use of broken colour in whatever guise had the effect of heightening the colour register. (It helped that the artists had access to newly available pigments of greater vividness and intensity, but we can’t make too much of this as their non-Impressionist contemporaries enjoyed the same access.)

Now, one person’s painterly quality is another person’s sketchiness, and if earlier artists had routinely displayed the oil sketches they had made in preparation for more fully worked out canvases – Constable and Corot come to mind here – we might not be so ready to credit the Impressionists with inventing a new way of painting. For the oil sketch was an integral part of the formal process of art composition, and the French had evolved a rich vocabulary to distinguish the different types: étude, pochade, esquisse, croquis, ébauche. Monet and his colleagues sometimes appended these terms to the titles of their paintings, especially in the first ‘Impressionist’ exhibition of 1874, but by signing and exhibiting them as artworks in their own right they closed the gap between the sketch and the finished painting (tableau, in academic parlance) and changed forever the way in which art was made and perceived.

One important difference between a sketch and an Impressionist painting has only recently come to light. Sketches are generally made at speed entirely in front of the motif, and it’s widely assumed that this is how the Impressionists worked. They themselves did much to foster this belief, Monet disingenuously claiming never to have had a studio. But we now know, thanks to close analysis of the paint surface in a number of iconic Impressionist canvases, that the vast majority of these paintings were completed over several sittings, and that much of the work would perforce have been done in the studio. The most iconic of them all, Monet’s early morning depiction of Le Havre harbour entitled Impression: Sunrise (1872), is now reckoned to have been a three-session picture, rather than the dashed-off study it purports to be.

The Impressionists have always had their detractors, of course. ‘Five or six lunatics, one of whom is a woman’ was how Le Figaro described the group at the time of their second exhibition, in 1876. Specifically, they were criticized for producing scruffy and unfinished work, and for being passive translators of the scenes before them, substituting straight observation for the more active task of imaginative construction. Cézanne said as much when he remarked that Monet and his like ‘caught’, while he and his supposedly more ambitious post-Impressionist colleagues ‘created’. This condescending attitude has continued ever since, with modern critics apt to dismiss Impressionist art as intellectually lightweight.

The trouble is, these readily comprehensible pictures offer the salaried explainers of art far less scope for scholarly exhibitionism than do other painting types. With the Old Masters they can have fun elucidating the often-arcane iconography, and with abstract art they can have even more fun saying pretty much whatever they please, secure in the knowledge that most of their assertions will be exquisitely immune to proof or disproof. Even the ones who approve of Impressionism seem to resent their subject’s accessibility, and end up writing the kind of impenetrable English that is all too common in academic art criticism. For example, the curator of Impression: Painting Quickly in France, 1860–90 – an enjoyable and influential exhibition, as it happens – after making the reasonable if unexceptional point that the Impressionists, with their well-documented interest in the science of optics, were more acutely aware than previous generations that a scene will look different when transposed onto the single plane of a canvas, inflicted the following sentence on his readers: ‘This dissociation from the material and three-dimensional and the concomitant embrace of the optical or two-dimensional is a primary paradigmatic in artistic consciousness, the radical nature of which has not yet been properly appreciated.’

The contrast with Monet’s limpid advice, as recalled by his neighbour the American artist Lilla Cabot Perry, could not be starker. It’s often quoted but is worth quoting again, as it incidentally reveals that Monet possessed a strong abstracting impulse:

When you go out to paint, try to forget what objects you have before you – a tree, a house, a field, or whatever. Merely think, here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact colour and shape, until it gives your own naïve impression of the scene before you.

Sounds easy, doesn’t it? His words lend weight to Neil MacGregor’s comment, quoted at the start of this Introduction, that these pictures look like something we could almost do ourselves. That’s the rationale behind Painting like the Impressionists, and while I don’t for one minute suggest that painting is easy, I do feel there’s been a conspiracy among art professionals, painters and critics alike, to create a mystique around it, as something requiring God-given talent honed by years of training and a lifetime of practice. This can only be discouraging for the would-be painter.

For my part, I’ve always believed that a successful painting comes about at a point where skill intersects with taste, and that no amount of the one will compensate for a serious deficiency of the other. Taste is a slippery concept, I know, and there are folk who maintain it is unimportant, or at any rate unteachable. Degas went so far as to state that ‘taste kills art’. That sounds to me like the kind of thing someone would say pour épater les bourgeois, a favourite pastime of the French artistic community in the late nineteenth century. (Épater has no direct equivalent in English, lying somewhere between ‘shock’ and ‘provoke’.) Degas seems here to equate taste with a deplorably genteel aesthetic sensibility, whereas I see it as a vital critical faculty, one that allows us to judge what makes a fitting subject, or a satisfying composition, or a harmonious palette, and so on. By this definition, the Impressionists showed consistently good taste throughout the painting process. It’s therefore my hope that this book, by introducing you to the philosophies and practices of the Impressionists, and by demonstrating how these have shaped my own painting style, will help you to attain a bit more taste, as well as a bit more skill.

CHAPTER 1

Materials and Equipment

The person who wishes to paint like the Impressionists will be comforted to know that many of the painting products we use today are not so very different from those available to the Impressionists themselves. The nineteenth century saw profound technical and commercial innovations in the art world, with the arrival onto the marketplace of new and more portable paints, different types of paintbrush and conveniently prepared canvases, all dispensed by a new breed of specialist art retailer. For the first time ever, oil painting could be taken up as a hobby as well as a profession. These developments helped to loosen the grip of the academic schools of painting, and in the wake of that, a painting style that took advantage of these new materials became, if not inevitable, then at least very likely. That painting style turned out to be Impressionism.

Freesias and Bath Abbey, oil on canvas, 76cm × 51cm

PAINTS AND PALETTE

In the first seven decades of the nineteenth century a large number of new chemical compounds such as chromium and the chromates were discovered by chemists and subsequently exploited by paint manufacturers, with the result that the palette of colours available to the Impressionists was almost unrecognizable from that available to painters a generation or two before them. Furthermore, from the mid century onwards the finished paint was sold in tin tubes very similar to those we buy today. This followed the invention in 1841 of a squeezable, re-sealable paint tube by an American portrait painter, John Goffe Rand, living in London. The importance of this invention to the Impressionist credo cannot be overemphasized. According to his son Jean, Renoir is supposed to have declared, ‘Without paints in tubes there would have been nothing of what the journalists were later to call Impressionism.’ Why? Because the portable paint tube made it infinitely easier for the artist to leave the studio and set up their easel in the great outdoors. Until then, the normal storage vessel had been a pig’s bladder, which, being insufficiently airtight, allowed the paint to gradually harden as the oil that bound it oxidized.

Renoir himself was fastidious about his paints, using colours hand-ground for him by the colour merchant Mulard. Monet, by contrast, seems to have been much more casual about the provenance and preparation of his paints. The Impressionists as a whole were united in their enthusiasm for the new pigments, nearly all of which were more intense and vivid than those in use before. This goes at least some way towards explaining why their palette was so much more vibrant than that of their immediate predecessors, although the widely held belief that they used pure, unmixed pigments in preference to mixing the colours has been exploded by recent analysis of the pigments used in a representative group of Impressionist works. An artist such as Monet might construct his colours from elaborate blends of many different contributing pigments.

Today’s painter has a wider choice of paints than their nineteenth-century counterpart for in addition to the continuing development of new colours, there are now different qualities of paint made for different sectors of the market: artists’ quality and students’ quality. Which should you buy? The standard advice is for beginners to start with students’ paints and only trade up to the much more expensive artists’ paints once they have reached a certain level of proficiency. I don’t question the logic of this but I do think you should invest in both in the first instance and compare them in order to understand better what the extra money gets you. Artists’ pigments are more finely ground and consequently more powerful than students’; also, the rare or difficult-to-produce pigments such as the cobalts and cadmiums are generally excluded from the students’ range. Bear in mind that, being more powerful, the artists’ paints stretch further, which helps offset the difference in cost. I’d be especially cautious of buying tubes labelled ‘hue’; this indicates that a cheaper substance has been substituted for the named pigment, and in my experience hues are always frustratingly weak.

There is no reason not to mix artists’ and students’ paints if you find that some colours warrant the extra cost while others do not, though you may find the difference in pigment strength complicates the business of mixing colours. (When mixing paints of unequal strength, you should start with the weaker and add the stronger; if you do it the other way round you are liable to end up with more of the mixture than you need.) Nor is there any reason to keep to the same brand: the paints I use are a mix of Old Holland, Michael Harding and Winsor & Newton brands. Even if you restrict yourself to artists’ quality, the prices of individual colours vary tremendously; mine range in price from about £6 a tube right up to a whopping £50 a tube – the culprit here is Old Holland Cerulean Blue, in case you were wondering. I would, though, resist the temptation to conduct lengthy experiments with different pigments: working with the same colours allows you to get to know their strengths and weaknesses, and how they perform together.

How many colours you choose is really a matter of taste. I currently have twelve on my palette, and lay them all out each time, squeezing out token amounts of those I feel I might not use: a small wastage of paint is, to me, less important than having the colours in their familiar positions with their familiar neighbours, allowing muscle-memory to take me to the colour I want almost without thinking. Other painters restrict or expand their palette according to the subject in hand: Monet, for example, used ten pigments in Gare St-Lazare (1877), but at least fifteen in Bathers at La Grenouillère (1869). However it is organized, your palette should enable you to obtain whatever colour you want while at the same time maintaining chromatic harmony.

Blues

Three blues are on my palette – French ultramarine, cobalt and cerulean. All three were staple colours in the Impressionist palette and differ from one another both in hue and tone. The synthetic form of ultramarine (as against the natural form, the rare and precious lapis lazuli), French ultramarine was first produced in the 1820s and was greatly favoured by Impressionist painters, not least because it was far cheaper than cobalt or cerulean. It is the warmest and darkest of the three blues, and like many painters both today and in the Impressionist era I use it as a base colour in my darks and as a substitute for black: mixed with burnt umber, it makes a rich warm black. As I tend to work from dark to light, ultramarine and burnt umber are actually the first two paints I squeeze on to my palette, laying the colours out from left to right (I am left-handed). Ultramarine makes a good all-round mixing pigment on account of its relative transparency, which prevents the colours containing it from becoming too muddy.

San Giorgio Maggiore and the Lagoon, oil on canvas, 76cm × 61cm

The blues of the sky and water have here been transmuted into soft greenish-blues and lilacs with the additions of Naples yellow and permanent rose, and by repeating these tints throughout the painting I’ve tried to bring the upper and lower halves of the composition closer together.

I rarely use ultramarine as a pure blue, for which I prefer the softer cobalt, especially for skies. Cobalt was discovered in 1802 and quickly adopted by painters, who appreciated its extraordinary stability. Its only disadvantage was its cost, unfortunately still the case today. Costlier still is cerulean, another cobalt derivative, with a greenish tinge not unlike turquoise. I’d be a richer man if I had found a good alternative to cerulean, yet it earns its place on the palette as a vital component of sky-blue colours, particularly for that section of the painting where the sky bleeds down to the horizon. I’ve tried doing without it from time to time, mixing cobalt with Naples yellow or cadmium lemon in the hope of replicating cerulean’s blue-blue-green qualities, but it’s never been quite the same.

Earth Colours

‘Earth colour’ is art world jargon for the six members of the Brown family (raw and burnt sienna, raw and burnt umber, red and yellow ochre) plus a dirty green, terre verte. All are inexpensive and relatively quick drying, though they differ in power and transparency. The Impressionists used them with discretion; their general feeling was that these colours could be mixed from other, higher-keyed pigments. The drab colours in Monet’s paintings of bathers at the Paris pleasure resort of La Grenouillère were often combinations of much brighter pigments. But while it is true that browns can always be mixed, my own feeling is that earth colours are an essential component of a balanced palette, and mixing them from the primaries (red, blue and yellow), as well as being more expensive, slows the painting process unnecessarily for a painting style where speed is desirable.

Browns Brasserie, Bristol, oil on canvas, 51cm × 61cm

One of the attractions of this subject was the subdued, restricted palette, which aptly reflects the name of the establishment. At first sight it looks as though an earth palette has been deployed, but I would have laid out my twelve standards in the normal way, and a closer look reveals that all twelve colours have a role to play somewhere or other in the composition. A second, more sentimental attraction of the subject for me is that, before Browns took it over, this used to be my university refectory. It served up pretty basic fare, and I can’t think that the interior was as paintable in those days.

Burnt umber is a particularly useful, powerful dark pigment, and nearly all my darks will contain at least some burnt umber. I’ve always preferred the siennas to the similar-hued ochres as they’re slightly more transparent, and therefore perform better when thinned. This is why I use a combination of raw and burnt sienna as a general-purpose warm ground on which to paint (the burnt sienna is much the stronger of the two, so the ratio is roughly four parts raw sienna to one part burnt sienna). My three earth colours alternate with the three blues on my palette (in order from left: ultramarine, burnt umber, cobalt blue, raw sienna, cerulean blue, burnt sienna) as I find I often use them together in various combinations in order to obtain the sludgier colours, as well as my darks.

It occurs to me that another reason for the Impressionists’ sparing use of earth colours is that earth colours are better suited to indirectly lit indoor subjects than to directly lit outdoor subjects. Such a theory is supported by the comments of the modern English Impressionist Ken Howard, who has written that he uses an earth palette for his studio paintings and a limited primary palette for his beach paintings. His phrase ‘earth palette’ should not be taken too literally: if you excluded all non-earth pigments from your palette you would end up not with a painting but with a camaïeu in brown. (Camaïeux are images based on varying tints of the same colour, often made by artists as an aid to understanding the tonal range of the painting in progress.) It’s really a question of using more or fewer of certain colours depending on the subject matter, and to that extent the indoor/outdoor, earth/primary division holds true.

Reds

The highest quality, most intense reds for use today are the cadmiums. They are always expensive but are so powerful that you never need much on your palette, and the various red ‘hues’ on the market are simply no substitute. Cadmium red did not appear until 1892 and was not in full commercial production until the twentieth century, so this was a colour denied to the Impressionists. Their reds were either vermilion or the lake pigments, all of which had good intensity and colour saturation.

Reds are not easy to use as part of a mix, especially as the cadmiums are all opaque colours. Our knowledge of the colour spectrum might lead us to suppose that red and blue make mauve or purple when in fact it makes a much dirtier colour akin to brown. That may explain why cobalt violet, which first appeared in 1859, was so enthusiastically taken up by the Impressionists. Monet had it on his palette by the end of the 1860s, using it especially for his purple-hued shadows in sunny compositions. I myself have used a ready-mixed mauve from time to time, but clean mauves and purples may be created from a mix of blues and pink-reds such as permanent rose or alizarin crimson, and I’ve since dropped mauve from my palette.

Yellows

In the Impressionist era chrome yellow was versatile and cheap to manufacture but not very stable, having a tendency to fade or discolour. This persuaded most Impressionists to switch either to cadmium yellow, available since the 1840s, or Naples yellow. Renoir abandoned chrome yellow in favour of Naples yellow in the 1880s, while Monet replaced his chromes with cadmiums. Cadmium is still the principal bright yellow used by artists today, ranging in temperature from lemon, the coolest, right up to orange. These yellow cadmiums have all the virtues and vices (the high cost) of their red cousins.

I have three yellows on my palette: cadmium lemon, cadmium yellow, and Naples yellow. Naples yellow is more of a buff colour, and I use it – specifically, Winsor & Newton Naples Yellow Light – mainly as a white substitute. Until a few years ago the active ingredient of this paint was zinc oxide and the paint itself was quite weak: I went through it by the bucket. Then in about 2003 the active ingredient was changed to titanium dioxide and suddenly the colour was colder, more opaque and far more powerful. This took a bit of getting used to, but was a welcome change as it made it less expensive and even more useful as a white substitute.

Greens

The use of ready-mixed green pigments is controversial. Many painters, myself included, avoid using pre-mixed greens, and indeed many painters could be said to avoid using greens altogether. In their landscape paintings Barbizon School representatives such as Corot and Courbet often employed silvery greys and earthy browns where, with a more literal representation on their part, we might have expected greens.