Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

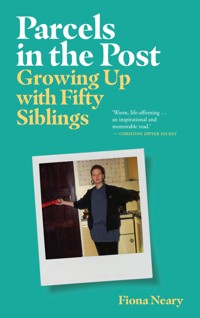

Welcome to the house of fun. It's the early 1980s and Fiona Neary and her family have recently moved back from England to the family farm. Fiona's huge-hearted mum decides to take in foster children – a decision that will change all their lives. Over the next decade, a procession of faces passes through the house. Every child has their own story, and each story claims a little piece of Fiona's heart. Some stay a few weeks; some months, and then years. All these children, as well as Fiona and her family, must pass through a chaotic system: where a judge's decision can alter a child's life, for better or worse; where emergency placements can break up siblings; where the foster family are often left in the dark and with little back-up. Filled with pathos and humour, Parcels in the Post is both a memoir of a loving household and snapshot of the fostering system in Ireland, from someone at the very heart of it all.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 349

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Parcels in the Post

PARCELS IN THE POST

First published in 2024 by

New Island Books

Glenshesk House

10 Richview Office Park

Clonskeagh

Dublin D14 V8C4

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

Copyright © Fiona Neary, 2024

The right of Fiona Neary to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

Print ISBN: 978-1-84840-926-2

eBook ISBN: 978-1-84840-927-9

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owners.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

New Island Books is a member of Publishing Ireland.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Chriss and Jimmy. Thank you.

In order to protect confidentiality many details regarding my life, my family and the children we fostered have been changed, including ages, personal traits, timelines and family configurations. Some of the characters are a composite of two or more people. I have attempted to balance protecting confidentiality, and an unreliable memory, with staying true to a lived experience of sharing my teenage years with multiple children in care and the reality of the lives of these children once in care.

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Afterword

Acknowledgements

1

o, he’s landed. Where’s his mum? What’s his name?’ I ask everything at once, dump my school bag out of the way of the door and get my first look. ‘He’s small. Is he big for two weeks? His head is very big for him.’

The new arrival is sucking contentedly on a bottle in Mum’s lap. He turns his head slightly towards my voice. Our first foster baby has arrived.

‘This is Gerard. He’s eight days old. Will you get me a bib, this one is drenched. How was school?’

‘Cool babygrow,’ I remark, handing her a fresh bib from a bunch of washing left on the table. ‘It was grand. What’s for dinner? Where’s his mum? Will I finish him? Where’s Áine and Seán?’

‘Up at Granny’s, with Dad. That’d be great. Here. It’s mince.’

She gathers him up and hands him to me. The bottle stays neatly in place. We’ve had some practice with my baby cousin Paul. The flat where Auntie Marie and her husband live is so rotten with damp that, after the hospital, Paul and Auntie Marie stayed with us to toughen up Paul’s tiny lungs. After about a month they moved back to the still-rotten-with-damp flat, and are all together again.

Gerard is tiny, smaller than Paul was. I feel clumsy. I grin at him as I take Mum’s place in the armchair.

‘Hello, little Gerard. Your name is bigger than you, isn’t it?’ He is only interested in his milk and slurps away. ‘Do you think he’s missing his mum? Do you think he can smell us and we are not the same?’ I settle us in, tilting the bottle with its milky formula smell.

‘He came from the hospital. It’s all antiseptic and disinfectant up there,’ Mum answers with her back to me as she checks the dinner.

‘Oh yeah. Is his mum in hospital? Did she bring him? How long will he stay? Can I put the TV on?’

‘No. The nurse brought him and his stuff.’ Still facing the range and saucepans, she nods her head towards the other side of the kitchen, in the direction of the telly. There’s a big pram and a bag. I forget about Scooby Doo and Top Cat. The prams are cool now compared to when Seán was a baby years ago.

‘Gerard, you’ll be lost in that thing it’s so big.’ He has blond hair and blue eyes and doesn’t look like us. He feels warm and bendy.

‘They never give up about the running in the hallways in school, Mum, I’m thirteen now, not a child.’ I throw my eyes up to the ceiling at the thought of it and then return to smiling at Gerard. Mum didn’t go to secondary school so there is nothing to be gained in whining about it with her, but I do anyway.

Áine and Seán arrive in with Dad. Neither of them is in secondary school, so they don’t have to wear a uniform. After a quick look through the pots they come over to examine Gerard in case there has been some drastic change in the half hour since they left him.

‘Did you see the size of his head?’ I ask them.

‘Will you give over about his head? There’s nothing wrong with him. He’ll grow into it.’

‘It is big though, Mum.’ Áine, for once, agrees with me. She is only eleven and hasn’t a clue. She strokes the side of his face. ‘Has anyone looked in the bag?’ Her hair has come loose from its band while she’s been up in the cowsheds with Dad.

‘I haven’t had time,’ Mum replies, mashing the spuds.

‘Where’s his mum?’ asks Seán, pulling at his trousers, which I think are looking a bit small for him now he’s nearly ten.

‘Who will be his godparents? Does he have relatives here, or someone? Will all the foster babies have big heads?’ I tease her for one last time about his head.

‘I don’t know. I’ll ask the nurse. Stop with that now.’

‘Well, you’ll have to talk to her soon.’ Dad looks to Mum as he takes off his farm jacket. ‘And who talks to the priest? It’s that young Fr McCarthy these days.’

‘I don’t know.’ She pauses, the jug of diluted packet soup in her hand hovering over the mince. ‘Us? Me? I’ll ask her. I’ll talk to Fr McCarthy about it.’ I look at her, trying to picture a baptism with no mammy and daddy. It’s only weeks since we were all up at the altar with cousin Paul, a big gang of us, and then ice cream afterwards.

‘Has he grandparents, are they farmers like ours? Do we know them?’ I try again.

‘Well, he came from the local hospital.’ That’s all Mum reveals.

‘You have only brought questions with you, Gerard.’ I snuggle him into me as he slurps away.

Áine and Seán go to explore the stuff that arrived with Gerard. The bag reveals babygrows, white cloth nappies, pins, plastic nappy covers with holes for the legs, dummies, Sudocrem, Gripe Water, bottles, teats and a big tin of formula covered in fat, happy pink babies. The pram has a rack underneath for shopping and stuff, and inside, along with the new blankets is a set of straps to hold a baby either lying down or sitting up. Seán and Áine poke at everything, holding things up for me to see. It’s all new, no hand-me-downs at all. Seán shakes the big tin of formula, pulls the plastic nappy cover over it and sticks his fingers out the leg holes, making silly faces. Áine smells the soft nappies and blankets.

I ease the bottle from the half-snoozing Gerard and carefully put him to my right shoulder. My left arm is under his bum, my hand on his tiny back, holding him in place. I can feel his little bones as I slowly rub his back and the fabric bundles up under my palm. I hope I’m doing it right. I’m rewarded with a belch and a splotch of smelly puke. It lands on the nappy thrown over my shoulder and not on my uniform.

‘Aha, nicely aimed, Gerard. Will I put him down while we eat?’ Without waiting for an answer I move us towards the pram. Mum comes over to help figure out the straps while Áine sets the table and Seán pulls up the stools.

I’m always in the middle, Áine on my right, Seán on my left. Mum and Dad sit on the other side of the counter. We are all on high stools and eat sitting sideways. We have never had a proper table. The kitchen in London was so narrow that the table and benches clipped up against the wall when they were not being used. Here, we have a counter on top of cupboards. It runs down the middle of the kitchen, with the range and other food cupboards on one side, and a small couch, armchairs and the telly on the other. There is no way to put your knees under the counter but the stools are so cool.

‘There aren’t five of us anymore now,’ says Seán. He points at Dad and counts: ‘One, Mum is two, Fiona is three, Áine four, and I am five.’ He turns on his stool and looks at the pram: ‘It’s six now, and I’m not the oldest. I mean the youngest. One, two, three, four, five AND now six.’

Dad reaches over into the pram.

‘He’s a fine fella, isn’t he? A good size.’ He rubs the side of the baby’s face with his finger and draws out a windy half smile.

‘The top comes off that thing and fits in the back of the car.’ The nurse has shown Mum how to unclip the wheels from the pram, she tells us.

‘But where will we fit, if that’s in the back?’ Áine wants to know. I don’t believe for a minute that that thing can fit in the back of a car.

‘The exercise is good for you,’ Dad teases her. ‘When I was your age––’ We all interrupt him before he can get into his stride, and dig into our dinners.

‘Granddad says the calves are ready.’ We look towards Seán. Granddad speaking at all is as much an event as the calves being ready. ‘And,’ Seán pauses, ‘he says I can go.’

Áine and I feign jealousy at not going to the mart on Saturday, and excitement at him going, to build Seán up even more. We are delighted we don’t have to go because the mart is dull.

After dinner, Dad puts on his heavy work jacket. This evening he’s not going up to the sheds to help with the milking as he has to go back to work at the council yard. There’s nothing on telly ’til later, so I offer to go up to the farm instead of him, just in case. Granny, Granddad and our Aunt Eileen won’t let me milk or anything much, but I’m handy for the odd thing. I go to find my wellies for the walk up the two fields between our house and the farm. Gerard starts to whinge.

‘Here we go,’ Dad remarks with good humour as he heads out the door.

I stop to rub Gerard’s belly softly, like Auntie Marie showed us with Paul. I wonder where Gerard will go next, after us. Maybe he will go to one of the posh houses with a VCR up past the church.

Later, with Seán gone to bed, Mum tells us something useful.

‘The community nurse who brought Gerard to stay with us today says his mammy can’t take care of him now. His mammy is a very nice lady and knows that he will be much happier with a big family, and a mammy and daddy.’

‘Where is his daddy?’ Áine asks.

After a pause Mum replies, ‘He had to go away and they can’t go with him. So, Gerard will stay with us while the nurse puts everything together. His new family are waiting for him like it’s Christmas coming. They can’t wait. There are a few things to be organised before he goes to live with them forever.’

2

’m dying now, right now, Mum.’ I can’t turn to glare at her. Oh, God. What if Gerard slips and bangs his head?

‘Will you give over?’ She doesn’t sound like she cares a bit.

‘And Top of the Pops is on soon and I’ll be dead and I won’t get to see it.’

‘Will you stop?’

‘Seriously, I’m having a heart attack right now, this minute. He’s so slithery. I can’t breathe. Look. Not breathing, not breathing, dying.’

‘Will you just pay attention?’

‘Ahhhh, Mum. What is the one thing every school report says, since I was four? Every single one? A pure genius if she only paid attention. You know I can’t pay attention. Everyone knows I can’t. That’s why I’m having a heart attack, right this minute.’

‘How can you fit so many words inside your mouth?’ Mum asks.

‘Big, always, big mouth, she always had a big mouth.’ I know well Seán is grinning, even though I’m afraid to look around. I can’t kill him because my hands are full of slippery, wet Gerard. I can’t even throw him a filthy look or anything over the other side of the kitchen without Gerard drowning. I’ll have to kill Seán after I’m finished drowning Gerard in the washing-up basin in the kitchen sink.

‘Use your free hand to move the water over him, and when he’s used to it, use the cloth. Softly. Softly! Will you go easy on him?’

And just as I am getting the hang of it, Gerard pees straight up and all over my T-shirt. ‘Well, he’s not drowned anyway,’ laughs Mum, and then she splashes water at me too.

Gerard starts waving his arms and legs about, cooing as I swish the water up over his chest, minding that it doesn’t go up onto his face too much. He starts laughing and bouncing. ‘We have to change the water now he peed in it, Mum.’ I bring my free hand up to my nose – can’t really smell it, just water and soap.

‘OK, take him out.’

‘Just another minute.’

‘No, out, he’ll get cold.’ That firmness again.

I race to the couch, leaving my damp clothes dumped on the floor while Mum takes Gerard. The children’s TV here is rubbish and we have no idea why Irish people are so excited by it. Dad did a deal with someone so that we get the English channels in our house. No one in my class has them, except the girl that just moved down from Dublin. They all watch The Incredible Hulk, which is so childish, when they could be watching this.

Mum hands Gerard back to me so she can go out and get turf. He’s giddy after his bath, moving about and reaching out to touch things. I grab a soother and give it to him to play with. The announcer is just introducing Top of the Pops, with the usual rev up. I like hearing the English accents again. I miss them. And seeing black faces, and just something different. Everything is the same here. There are no Jamaicans, no Greeks, not even any Scottish, just Irish, Irish, Irish. There are no Bangladeshis, and no Indians – not even up at the doctors. There aren’t even any Protestants, although one of the churches up town is Protestant. And, you have to fit in, be like the Irish, and not a Brit.

Last year when we were both in national school and walking home together, Áine stopped beside the hospital wall so she could tie her lace. While she was bent over I waited, looking at the slowly fading Brits Out graffiti that we passed every day. When she stood up she asked, ‘What are Brits?’ I noticed her accent was going. I had lost mine as fast. I thought about UTV, Ulster Television, playing the British national anthem when the programmes finished for the night.

‘So,’ I began, ‘the Brits came over here and took everything, and then didn’t give some of it back, so everyone is fighting over that bit that they didn’t give back.’

‘Took it where?’ she asks. I look at her. I’ll have to try another way.

‘Um, the English came over here, and they were the boss, and now they are still the boss in one bit and we don’t like that.’

‘We came from England. Are we Brits? We are not the boss, at all. The teacher, Sister Maureen, is the boss.’ She is very serious.

‘We came from London, but we live here now, so, maybe we are still a bit Brit.’ I shrug.

‘Do they want us out? I like it here. If the Brits are out will we still have Blue Peter and TheMagic Roundabout?’

‘Our house is built in Granddad’s field, so, they’re our fields, so, we’re Irish. I think.’ When Dad got a job with the council, Granddad gave him a site to build our house. He told us that blocks were so cheap we could each have a bedroom and one to spare. No bunk beds and sharing like London.

Áine saw someone from school up ahead and lost interest. I’d have to ask someone about all this stuff, which is something Irish children don’t do.

As well as always being in trouble for not paying attention, in Ireland I am always in trouble for asking questions off teachers that you are not supposed to ask. I’m better at losing the accent than at trying not to ask questions. I just can’t stop myself. Like that day when I asked why we have to write with pencils, not pens. The teacher just told me to get on with it.

Gerard yawns. Apart from cutting his nails I can do almost everything now. I tap his nose as the music starts. I sway him back and over as I wait. I can hold him on my hip, in one arm, and make up a bottle with just one hand already. It’s easy, if you use the side of the kettle to hold the measuring spoon in place while you scrape off any extra formula with the knife, before throwing the exact right amount into the boiling water in the bottle. And then shake the bottle while dancing Gerard around the kitchen. I can easily change his nappy, just getting pricked by the pins when he kicks out or wriggles is annoying. He gets a big slather of Sudocrem every time for his rash, which just won’t go, regardless. Áine is better than me at dressing him, though, she’s better with small things than me. Seán is learning to do things too.

Finally, the Top of the Pops opening theme music ends. Gerard stops yawning and starts to whimper.

‘No way, Gerard, no way.’ There’s no one else around. I’m annoyed because I can’t concentrate on the DJs. I carry him over to get a soother from his pram and rummage for the bottle of Gripe Water. It always works and this just isn’t fair. Back on the couch and there’s still no one else. When did Seán leave?

‘MUM, ÁINE, ANYONE? Feck sake, Gerard. Where’s your bloody mother now?’

Laying him on the couch beside me as he starts working up to crying, I stick the soother right into the top of the glass bottle, tip it all upside down until the soother is well drenched, tip it back up, take the soother out, throw the lid on – even though I want to chuck the whole lot across the room – and shove it into Gerard’s wide open, ready to howl, mouth. He promptly starts to suck.

‘Why is he up? What in the name of sunshine is that?’ Mum laughs at the TV as she looks over the pile of turf stacked on her arm. She throws the sods neatly into the box. ‘Don’t tell me you like that? That’s not music.’

‘Mum!’ I snap at her so she will just shut up, and sit up onto the arm of the couch to watch a bit with me.

3

alking to school or to town takes us past the farmhouse. As I’m walking home from school Granny comes down to the gable. ‘Your mother’s here, with the baby. Isn’t he a lovely thingeen?’ Her massive hands open the low gate out, towards me. She has flour on her big wide apron. It’s only an odd dab, not half a bag like I would have all over me and everything around me if I was making bread.

‘Hi, Granny. Where’s Rex?’ I shrug my school bag off my shoulder. It’s so heavy. The large sheepdog bounds up. Every time they get a dog it’s called Rex. This one only arrived after we came to live here, so he will be the Rex for a long time, if he isn’t killed on ‘the road’.

‘The road’ always means the busy one, as the farmhouse is exactly where two roads meet. The quiet road goes up a steep hill, out to the bogs where we cut turf every summer, and is all farmers and tractors. The busy road is flat, goes to the next town, and is a mix of farmers and town houses. There are buses on this route, we use them to tell the time.

I follow Nan up by her garden at the front, blinking as we enter the kitchen and my eyes adjust. The windows are all tiny, set into thick stone, and even on a bright day it’s dark in here. Only the new back kitchen that Dad built last year has a big bright window, which looks directly onto the yard and sheds. Rex stops at the door, knowing the limits.

The air is fruity with smells of fresh cow’s milk, cats, rain, sun, hay, moistened calf feed and various kinds of animal shit – all jumbled into the pastry Nan has returned to rolling out. Mum is up at the range, showing Gerard to Granddad, who is in his tall chair, nodding as if he can hear everything. The kitchen table where Nan works is an enormous, worn, wooden beast, running down the full length of the room. I lean on it and stroke the softened wood while I get out of my coat and kick that bloody bag to one side, drawing a cautionary look from Granny and Mum, which I ignore. I have inked David Bowie all over every bit of the denim, including the straps, and Granny shakes her head every time it catches her eye. Like Mum she can easily do everything at once. She can make a tart, watch out for the 4:15 bus passing, give out about my school bag, mind whatever is cooking on the range, manage all her chickens, geese, turkeys and chooks, milk and muck out eight cattle twice a day, and still have time to go out to either gable end. She leans on a gate to gather the news from whoever is going into town or going home, buying a couple of fresh duck eggs off her en route, paying in updates on who has died, who hasn’t and who might.

Áine and Seán must be out hunting for hen’s eggs. It’s a full roll of Eclairs for anyone who finds a hidden nest. It’s the wrong time of year for blackberries, thank God. Every year Mum despairs at the potential waste of ‘all that lovely fruit’ and makes jam. And every year, for a couple of weeks, we play along.

‘It’s lovely, Mum, can I have more?’

Then it’s: ‘Ah, it’s really lovely, great. No. Don’t need any more, thanks.’

Until we can take no more.

‘It’s like soup, Mum. It goes everywhere.’ Or: ‘It won’t spread. It’s like tar with seeds in it.’ Or: ‘It sits in a big lump and tears up the bread if you try and spread it.’ And inevitably: ‘Mum, it’s sour. Please can I have the Dunnes jam?’

Every autumn we give it our best shot until we have to give up.

‘... and Father McCarthy says he can do him Sunday week, after twelve o’clock Mass,’ Mum is saying. Granny likes Father McCarthy and says he does a lovely Mass.

‘Not his family then?’ Granny asks. ‘None of them at all?’ She shakes her head slowly. ‘The Europe and the EEC will be the death of us,’ she declares, as she pops a finished tart into the oven. We’re doing the EEC in school now, in Geography. I wonder if Granny is even sure which way Europe is. ‘Giving them all that money for having babies, any which way at all.’ I look over at Mum with a ‘What?’ on my face. Mum gives a slight shake of her head for me to say nothing.

‘What money, Nan?’ I grin at Mum, who throws me a look.

‘Oh, it’s a fortune, a full fortune. And they likely all get one of them big new prams. Would you look at the size of it, and the wheels come off and everything.’ The very new pram is indeed parked at the dresser, where a cat is eyeing it up. That cat won’t be there long if Granny sees it.

‘It’s eight pounds.’ Mum’s voice is a bit stiff.

‘It’s not eight. What’s eight? It’s eleven,’ I say.

Granny’s hands stop. I quickly grab a big piece of apple she has peeled, mush it right into the sugar bowl so not one bit isn’t sugared, and pop it into my mouth. She is quick enough to slap the side of her knife off the back of my hand and we both laugh.

‘Eleven pounds. Eleven. They get eleven pounds for having a baby?’ She is shocked. ‘You could buy a full heifer for that in jig time. Michael, did you hear this, eleven pounds?’ I don’t see what the big deal is. Mum has sat heavily into Granny’s chair by the range. There’s never any money in our house.

‘It’s eight for the unmarried mothers. We get eleven,’ Mum clarifies.

‘Why do we get more?’ I ask, eyeing up another piece of apple.

‘Eight pounds a week. Every week. When did I ever see eight pounds a week?’ Granny’s gone back to the sour cooking apples, her grey head still shaking.

‘For the things,’ is all Mum adds. I know she wants me to stop.

‘Well, Granny, she’s not getting any eight pounds now while we have the baby, is she? We’re getting it. Will she get it back if she takes the baby back, Mum?’ I’m all innocence as I size up how to get another piece of apple without landing a slap of the knife.

Granny is indignant. ‘Takes the baby back? What do you mean? You cannot be giving and taking a baby, who ever heard of it? It’s the Europe, the Italians.’ I knew it would put her out.

‘Give me a hand with him.’ Mum is having no more of it. I grab another piece of apple and start moving, grinning at her.

‘At least he will be baptised.’ This appeases Granny.

‘Who’ll stand?’ I ask.

‘We will,’ Mum replies, strapping him in.

‘You and Dad?’

‘Yes.’

‘You’ll come, and Eileen?’ Mum looks over to the table.

Aunt Eileen will be home soon, after the shop closes. Granny has to think about this. The baptism of a baby whose mother was likely not married. In the house of God, and her there too, in her very best clothes. She is Dad’s mum, and not as easy going as Mum’s mum.

‘Well …’ she buys some time, ‘it’s usually the early Mass for us, to be back for the milking.’

‘Granny, there will be ice cream after.’ I tease her. She has a fierce sweet tooth. ‘And, if you go twice on the one Sunday you will go straight to heaven entirely.’

‘Mmmh.’ She swings the oven door open and pops another tart in.

I go ahead of Mum, carrying the front of the pram down the old stone steps, as Mum guides the end. She’s facing forwards while I step backwards. The pram just about fits. It’s almost as wide as the cattle, who stain the whitewashed gate posts blacker every time they go through, before and after milking. Áine and Seán have gone ahead of us through the fields. We watch them running along the top of the hill as we cross the busy road and turn towards home.

‘You are a monkey,’ Mum tells me.

‘I know, I know.’ I’m giggling. ‘The Europe. It’s just a bloody baby, Mum, where’s the harm?’

‘Will you mind them shoes, so you’ll have them for the church.’

‘Do you think they’ll come?’

‘I don’t know.’ She sighs as we manoeuvre the pram around a large pothole. There’s no pavement running along the houses in this row that looks out onto the busy road and then across to my grandparents’ farmyard and fields. In some parts there are so many potholes that there isn’t enough room in between them for such a big pram. The town starts a bit further on, at the judge’s house, along with the streetlights and paving.

‘Those bloody dogs were up town, Mum. The whole gang, by the Dunnes lane, pure wild. That lead one is a big bastard. He’s more like a calf with savage teeth.’

She frowns. ‘I can’t believe they haven’t shot them yet.’

‘There will be murder if they don’t do it before the lambs. But that’s not for ages, Mum, and I think there’s more.’ Another series of potholes, and no space to go around them so we lift the pram together. I think it will be just us, Mum.’

‘Mmmhh.’ She’s giving nothing away.

‘Is there really no one? It’s awful sad.’ Gerard is watching the sky pass overhead, oblivious. ‘I can hold him in the back, though, so we all fit and no pram. And Dad’s new camera.’ Our latest banger of a car is bigger.

‘That’s if there’s any petrol.’

‘Oh yeah. We should get a big sled, and train them rotten bastard dogs.’

‘Stop that. And no photos,’ Mum says.

‘What? But we can get some film, from the eleven pounds?’

‘No, there’s to be no photos. The nurse says so.’

‘Is she mad? Has she never been to a christening?’

‘It’s the rules. It’s not allowed.’

‘But why? Who makes these bloody stupid rules?’

‘She doesn’t know why or who made the rule. It’s just the rule.’

‘Are you telling me that even with Dad’s new camera we cannot take a picture of a baby? They all look the same anyway, don’t they really? Small, bald. And, how would they know? Come on, Mum, we don’t have to tell them. If you don’t say it to Dad he won’t know.’ Dad won’t have a bit of that; if there’s a rule, we know well it will be followed.

‘Stop.’

‘Fuck sake.’

She stops pushing the pram abruptly, Gerard jerks inside.

‘I will not tell you again.’ The finger is out.

‘OK, OK.’ I roll my eyes, thinking about how I might get a picture, and try to hide it when Dad collects them from the chemist. I’d have to go with him and get at them first, but then he’d want to know how come one was missing, and he’d definitely look at the negatives to see. And he’d kill me for being at the camera, after he’d killed me for breaking the rule.

4

e won’t settle for me. He is fed, watered, changed, and winded. He is annoying.’ I spell it out for Dad. There isn’t a chance he will take Gerard off me, but I am fed up.

Dad looks up from measuring a section of wood.

‘Why not take him for a walk? You could bring a hat and gloves up to Seán. They were left in the kitchen.’ He sticks a pencil behind his ear and starts sawing along the neat line. I hold Gerard to my shoulder. He is momentarily quiet, distracted by the noise and all the stuff arranged around the garage. Dad is always fixing something, or building another shed, so there are lots of tools and screwdrivers stored in here.

‘Would you help me get the pram over the first set of potholes? Not all the way to the judge’s, just the first big ones?’ If I take Gerard to town I could show off my new corduroy trousers.

‘Let me finish up and I’ll be with you.’

Gerard starts whinging as soon as I put him back in his pram in the kitchen. Mum and Áine have gone to Dunnes to do the big shop, and Seán is with Granddad, so I leave him to go and find the pram cover and his outdoor one-piece. It goes over his yellow babygrow and covers him from his tiny feet right up to over his head. When I pull the zip up, all the way from his belly to his chin, only his face and hands are out in the fresh air. The blue material is all puffy and he looks like an astronaut.

‘I wouldn’t mind one of these for myself, Gerard, and someone to push me to town, all wrapped up and warm.’ I strap him in, pull the plastic cover up over the pram and slip the elastic loops around all the hooks, ten in total. Maybe it won’t rain. He whimpers and waves his arms and legs about. I go to the cupboard to get my pocket money. Inside there are four worn out red Brylcreem lids, turned upside down into tubs – one each for bills and the last for everything else. We know about the bills and how much is left each week, which is never much. We can all reach this cupboard, can see what’s in each tub, know what it’s for and if we need money for school, after we tell Mum, we can take the money out of the fourth tub ourselves.

As soon as we start moving Gerard quietens. I look over at Dad, who is putting on his jacket.

He nods. ‘If you only knew the miles I walked with you.’ Between us we get the pram out to the road and cross over to the gravel path side. The potholes are full to the brim with mucky grey rainwater and Dad can lift the pram without my help. He heads back home after I tell him I can manage from here on. I feel very grown up doing it all on my own. Zigzagging along it occurs to me that the pram is so big it might not fit in the door of the record shop. I try to remember if I have ever seen a pram in ‘Up Town Records’. It is not a big shop.

Once I reach the proper path the going is easy and I speed up. Not a squeak from the astronaut, who seems to be watching the clouds pass by. As we pass the petrol station I think about the queues and the men who lean on their cars or tractors, arms folded, or stand in twos and threes, chatting. The mart is only a few minutes away now.

As we get near I easily spot Granddad. He is the tallest, standing beside his red tractor and old wooden trailer, in among the thrown-together boxes on wheels that are pulled in at the bottom of Main Street. There’s the smell of calves skittering nervously on damp hay, waiting to be sold. Or not. It is like this every Saturday morning.

I loved it when we moved here first. I strained on my tiptoes, peeping over tailgates to get a close look at the snowy white or black noses inside. Usually, I’d know some of the other farmers. I got used to the tight grasp of their rough hands, the nodding from under caps, the big eyebrows. Something makes them all walk like John Wayne just off a horse after days of driving cattle across the telly. As far as we know none of them has a horse. Maybe some have donkeys. Maybe it’s from driving tractors. They sway from side to side as they stride about in old suit jackets and waistcoats, handling cattle. They pull up forelegs, slap haunches for good measure and heave calves of any size over with a push of their shoulder. Because of Granddad, we are one of them. I’d sit beside him on an old crate, which he would bring in the trailer just for me, waiting to sell a calf or two.

‘You’ll give me a good price today, ha?’

‘The besht, that one, the besht.’

From school I understand they speak differently, because the Irish alphabet is different. They speak English, mixed up with the Irish alphabet, flavoured with a Mayo accent. No one we know speaks Irish. We never hear it outside school.

The farmers are often quiet-spoken, or like Granddad, don’t really speak much at all, just nod, incline a head to the side. Some are tall and all angles like him, others are short and stout, their wellies rolled down to fit. They lean right into each other when they are talking, like they are whispering magic into each other’s ears. When the rain gets very heavy they throw any sort of a cover over their shoulders and heads; old macs, old sacks, whatever is handy.

Eventually, I spot Seán in the thick of it and try to catch his eye. I’m not going to attempt to get the pram over to him, through all this.

I decide to sit Gerard up and leave him here on the pavement while I go over. Rearranging him and fixing his straps, I think about Saturday mornings in London. We used to go to the swimming pool, beside the shopping centre, up by the allotments. Two tower blocks sat right on top of the shops and stretched high into the sky. After a swim and spending ages wondering if you were fit to jump off one of the diving boards, you could go upstairs and get a cup of soup for 10p. Sitting in the big glass-covered viewing area, with our plastic cups, a bunch of us from our street would watch the big lads diving off all three boards.

Here, there is no swimming pool, no shopping centre, no tower blocks, and no one has ever heard of an allotment. We are in Ireland long enough to know that Irish children don’t get regular pocket money and money is not kept in cupboards that they can open, if there is any that is. We know not to talk about money.

Slower than most to pick up on the signs, I have caused repeated embarrassment by openly asking questions like ‘How much pocket money do you get and when do you get it?’ and ‘Where does your mum work and whose car does she go to work in?’ The mumbling, mostly silent responses of Irish children has taught me not to do that.

Back on the Tottenham street we would sit on the kerb with the other kids and compare our weekly pocket money, which every kid got, usually on Saturday. There were pros and cons to the various amounts, what chores or messages we had to do to get it, when we got it and who got the best.

We sat on the kerb in a row, watching our mums getting ready for the factory’s evening shift, piling into the cars of the couple of women who owned them. The talk paused only to watch Diane and Davey’s mum sit into her car. She was so enormous that the Ford Cortina abruptly sank towards the road and surely someday it would actually hit the ground. We resumed speculation in disappointment as the under-carriage hovered a bare inch off the tarmac, the ignition turned, the engine turned over and the cars crawled off, taking our mums to their pay packets. When the conversation about pocket money ran dry, we might drift into comparing which of the factories gave the best children’s Christmas parties, as most of us had at least a mum or dad working in the Ford or the plastic glove factory.

When we moved to Ireland, the muted responses of Irish children made me think about the kids in London who made themselves absent during our pocket money research and debates. Perhaps not all were in the same boat as us back then either.

Walking back over to Gerard, I see our neighbour Mrs McDermott standing at the pram. She is neat and tidy. A scarf with lots of horses’ heads sits over her hair and is tied under her chin. I know her four daughters, who are all in my school, but none of them are in my class.

‘Is that Paul?’ she asks with a smile, peering into the pram. I unhook the plastic cover and turn it down so she can see properly. Before I can tell her it isn’t Paul, she says, ‘Isn’t he the image of your Auntie Marie, and your mother too, I think.’ I scratch my head as she reaches in and touches Gerard’s chin.

‘Paul is bigger, Mrs McDermott. This is Gerard; he is only a few weeks old. Paul is more than two months now.’

‘Doesn’t the time fly? Is he another cousin?’ Her eyebrows are raised.

‘No. Mum is minding him, for … for the community nurse.’