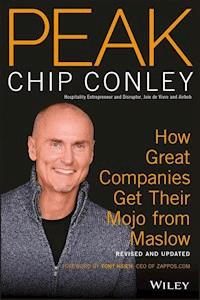

14,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

Proven principles for sustainable success, with new leadership insight PEAK is the popular, transformative guide to doing business better, written by a seasoned entrepreneur/CEO who has disrupted his favorite industry not once, but twice. Author Chip Conley, founder and former CEO of one of the world's largest boutique hotel companies, turned to psychologist Abraham Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs at a time when his company was in dire need. And years later, when the young founders of Airbnb asked him to help turn their start-up home sharing company into a world-class hospitality giant, Conley once again used the principles he'd developed in PEAK. In the decade since this book's first edition, Conley's PEAK strategy has been developed on six continents in organizations in virtually every industry. The author's foundational premise is that great leaders become amateur psychologists by understanding the unique needs of three key relationships--with employees, customers, and investors--and this message has resonated with every kind of leader and company including some of the world's best-known, from Apple to Facebook. Avid users of PEAK have found that the principles create greater loyalty and differentiation with their key stakeholders. This new second edition includes in-depth examples of real-world PEAK companies, including the author's own at Airbnb, and exclusive PEAK leadership practices that will take you--and your company's performance--to new heights. Whether you're at a startup or a Fortune 500 company, at a for-profit, nonprofit, or governmental organization, this book can help you and your people reach potential you never realized you had. * Understand how Maslow's hierarchy makes for winning business practices * Learn how PEAK drove some of today's top businesses to success * Help employees reach their full potential--and beyond * Transform the customer experience and keep investors happy The PEAK framework succeeds because it elevates the business from the inside out. These same principles apply in the boardroom, the breakroom, and your living room at home, and have proven to be the foundation of healthy, fulfilled lives. Even if you think you're doing great, you could always be doing better--and PEAK gives you a roadmap to the next level.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 502

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

More Praise for Peak

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Foreword

Introduction

Preface

Part One: Maslow and Me

Chapter One: Toward a Psychology of Business

A Brief Primer on Maslow

Maslow in the Workplace

Taking Maslow to Heart

How This Book Is Organized

Chapter Two: Karmic Capitalism

The Workplace as a Mirror

Why Are We So Focused on the Short Term?

Satisfying Our Tendency Toward the Tangible

The Pursuit of Happiness at Work

Making the Hierarchy of Needs Tangible

Chapter Three: The Relationship Truths

Joie de Vivre's Web of Relationships

The Value of Relationships in the Workplace

Introducing the Relationship Truths

The Power of the Pyramid

Part Two: Relationship Truth 1: The Employee Pyramid

Chapter Four: Creating Base Motivation

The Base of the Employee Pyramid

Google Is Peaking

Bigger Than Money

How Solid Is the Base of Your Pyramid?

Chapter Five: Creating Loyalty

Why Recognition Rules

Creating a Culture of Recognition

Chapter Six: Creating Inspiration

A Swinging Company

Why Meaning Has Become More Meaningful

The Two Components of Meaning in the Workplace

Creating Meaning in the Day-to-Day Work

Part Three: Relationship Truth 2: The Customer Pyramid

Chapter Seven: Creating Satisfaction

Using the Hierarchy of Needs to Understand Your Customer

The Nature of Customer Expectations

Satisfaction Doesn't Create Loyalty

Boutique Hotels as Disruptive Innovators

Joie de Vivre on the Brink of Disaster

Chapter Eight: Creating Commitment

What Are Customer Desires?

Using Technology to Meet Desires

High-Tech, High-Touch Cultures

Creating a Great Service Culture

Chapter Nine: Creating Evangelists

Peak's Apple and Harley-Davidson Customer Pyramids

Creating Your Own Customer Pyramid

Understanding the Unrecognized Needs of Your Customer

Four Themes at the Top of the Customer Pyramid

Part Four: Relationship Truth 3: The Investor Pyramid

Chapter Ten: Creating Trust

The Investor Pyramid Is Relevant to All Employees

Are Investors Human?

Attracting an Aligned Investor

Creating Transactional Alignment

The Definition of Effective Performance

Chapter Eleven: Creating Confidence

Emotionally Intelligent Investing

From Transaction to Collaboration

Creating an Emotional Connection with Investors

Chapter Twelve: Creating Pride of Ownership

How Big Is the Legacy Investor Market?

Purpose Drives Profit

Investing in Community Pays Off

Part Five: Putting The Truths into Action

Chapter Thirteen: The Heart of the Matter

The Emergence of the Joie de Vivre Heart

Creating Corporate Culture

What's the Right Culture for Your Company?

Bringing It All Together

Chapter Fourteen: Peak Leadership Practices

The Practices

Chapter Fifteen: Creating a Self-Actualized Life

Job, Career, Calling

The Qualities of a Self-Actualized Person

Using Pyramids to Set Priorities

Climbing Higher

Appendix: Peak Managerial Assessment

References

Acknowledgments

The Author

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Foreword

Part 1

Chapter 1

Pages

i

ii

iii

iv

v

vi

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

xvii

xviii

xix

xx

xxi

xxii

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

More Praise for Peak

“I love the Joie de Vivre Heart icon that Chip uses to illustrate how a passionate corporate culture breeds happy employees, which leads to satisfied customers, which results in a profitable and sustainable business.”

—Sir Richard Branson, founder and chairman, Virgin Group Ltd.

“Late in his life, Abe Maslow imagined how his iconic hierarchy of needs could be translated to the collective, especially to companies, but he never fully realized that vision. Chip Conley has channeled Abe's point of view and made it relevant to the business world. There is no person on the planet better versed in how to create a self-actualized organization than Chip and Peak is his virtuoso manifesto.”

—Michael Murphy, cofounder, Esalen Institute

“Peak was one of the sources of inspiration for Life@Facebook, our new comprehensive approach to caring for our people and those who matter to them.”

—Tudor Havriliuc, vice president, human resources, Facebook

“The world could use more conscious capitalists who realize the most neglected fact in business is we're all human. Chip Conley's Peak is one of the most practical and inspiring books of this new era of stakeholder-centered businesses. This was required reading for many of our top execs.”

—Kip Tindell, cofounder and chairman, The Container Store

“WeWork truly resonates with Chip's Peak principles as we believe our mission is to create a world where people work to make a life, not just a living. As a fellow former hotel industry CEO, I have the utmost admiration for Chip's approach to leadership and how it translates into success.”

—Michael Gross, vice-chair, WeWork

“Within this engrossing, inspiring, and all-around wonderful book is the gripping story of an extraordinary company facing the most trying circumstances imaginable and emerging stronger than ever. If you want to build a great business, work in a great business, or simply understand what greatness in business is all about, you need to read Peak.”

—Bo Burlingham, editor-at-large of Inc. and author of Small Giants: Companies That Choose to Be Great Instead of Big

“There aren't many books that do a more brilliant job of showing how both a company and a leader can create loyalty and differentiation by just applying a little common sense psychology. Like most wonders of the world, Peak is both simple and complex at the same time, but, most importantly, it's effective as a way of seeing business and life.”

—Leslie Blodgett, founder and former CEO, bareMinerals

“Chip Conley has captured something special here. Peak shows how to apply fundamental human principles toward building a great company and offers poignant insights for all leaders.”

—John Donahoe, former CEO, eBay

“What do Yvon Chouinard, Timothy Leary, and a company where one-third of the employees clean toilets for a living have in common? As brilliant entrepreneur Chip Conley will teach you in this groundbreaking book: Abraham Maslow. Essential reading for anyone trying to create an organization with meaning.”

—Seth Godin, author of Purple Cow and Tribes

“Chip's book is a rare combination of poignant story, potent theory, and prescriptive action steps—it is applicable to both public and private sector work.”

—Gavin Newsom, lieutenant governor of California

“Chip Conley proves that Abraham Maslow's brilliant theories regarding work and leadership cannot only be applied in the real world but, when embraced, often lead to enormous competitive advantages. Chip's book is an instructive guide for any leader who seeks to build enlightened organizations that tap the potential of employees and capture the hearts and minds of customers and shareholders.”

—Deborah Collins Stephens, coauthor of Maslow on Management and The Maslow Business Reader and cofounder of The Center for Innovative Leadership

Also by Chip Conley

The Rebel Rules

Marketing That Matters

Peak

Emotional Equations

Peak

Chip Conley

How Great Companies Get Their Mojo from Maslow

Revised and Updated

Cover image: © Lisa KeatingCover design: Wiley

Copyright © 2017 by Chip Conley. All rights reserved.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.

Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom.

For general information about our other products and services, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

ISBN 978-1-119-43492-4 (paper)

ISBN 978-1-119-43493-1 (ePDF)

ISBN 978-1-119-43494-8 (ePub)

To Abraham H. Maslow, whose lifetime of learning offered a precious gift to the world.

And to my Joie de Vivre crew, who “sought the peak” with me every day.

Foreword

I first met Chip Conley at an event where we were both speaking in 2007, just one year before we hit $1 billion in gross merchandise sales at Zappos.com. When he presented his concepts from Peak, I was instantly struck with how similar our philosophies about building a brand and business were. I later found out that we were both passionate students of the field of positive psychology—essentially, the science of happiness—and that we had both applied our learning to our respective businesses as well as our personal lives. I felt like we were kindred spirits.

At Zappos, our goal is to wow our customers, our employees, our vendors, and ultimately our investors. We strive to deliver the very best customer service and customer experience, and ultimately our brand is about delivering happiness to the world. Our hope is that 10 years from now, people won't even realize that we started selling shoes online, and perhaps 20 to 30 years from now, there may even be a Zappos Airlines that's focused on just delivering the very best customer experience.

Our number-one priority at Zappos is company culture. Our belief is that if we get the culture right, then most of the other stuff, like building a long-term enduring brand, delivering great service, and finding passionate employees and customers, will happen naturally on its own.

Building a brand today is very different from building a brand 50 years ago. It used to be that a few people got together in a room, decided what the brand positioning was going to be, and then spent a lot of money buying advertising telling people what their brand was. And if you were able to spend enough money, then you were able to build your brand.

Today, what you do and who you are matter much more than what you say. Your brand is the combination of everyone's experience with your company, which is ultimately a byproduct of your company's culture.

A company's culture and a company's brand are really just two sides of the same coin. The brand may lag the culture at first, but eventually it will catch up. At the end of the day, every brand is basically a short cut to emotions. All of the world's greatest enduring brands ultimately appeal to one or more human emotions. Peak provides a great framework for thinking about how to accomplish that.

One of our core values at Zappos is to Pursue Growth and Learning, so we offer many different classes to help our employees grow both personally and professionally. We are such a fan of Chip's work that Peak has become required reading for many of our employees, and our training team now offers a class specifically designed to cover all the concepts from the book that you are now holding in your hands.

Every employee and visitor to our headquarters in Las Vegas is offered a free copy of Peak, and we even have posters on the walls of our headquarters in Las Vegas to serve as a daily reminder to our employees to always keep Chip's modified version of Maslow's Hierarchy in mind.

If you're interested in building an enduring brand and business, this book will be one of the best investments you'll ever make. I encourage you to do what we've done at Zappos: get a copy for each and every one of your employees. This book is one of the rare few that can help you and your employees grow both personally and professionally.

Tony Hsieh, CEO of Zappos.com ([email protected])

P.S. If you're ever in the Las Vegas area, I would like to invite you to come and tour our headquarters to observe firsthand many of the concepts from Peak in action. To schedule your tour, just go to https://www.zapposinsights.com/tours.

Introduction

Books teach me. Even my own. Writing a book helps make sense of what I've learned at the congested crossroads of psychology and business. And I enjoy sharing the wisdom found on the journey. You're welcome to think of me as your crossing guard at that confusing intersection.

It's been 10 years since Peak was published and I'm thrilled the book is still a favorite with so many people, and in so many different industries and countries. This updated edition offers new insights from me, as well as many examples of new companies—from Facebook to WeWork—that use the Peak model in their organizational strategy. You'll also find a whole new chapter on Peak Leadership Practices (Chapter Fourteen) and a new Managerial Assessment tool regarding the Employee Pyramid in the Appendix.

Quite a bit has changed for me in the past decade. Just six months after Peak came out in 2007, it was clear we were entering the Great Recession, not long after recovering from the dot-com bust. Who knew my company would experience two once-in-a-lifetime downturns in the same decade? Déjà vu. Joie de Vivre (JdV). Don't worry, this isn't a French lesson; let's just say I felt a whole lot of déjà vu at JdV between 2008 and 2010.

During difficult times, it's natural to feel paralyzed and to operate exclusively in survival mode. Most of us are working in infectious fear factories, where risk aversion runs rampant at a time when creativity, innovation, and teamwork are more needed than ever. That's where you, the leader, come in. W. Edward Deming, father of the total quality movement, once said that the primary duty of every leader is to remove fear from the workplace. But organizational wellness doesn't emerge simply from the absence of fear. Fear must be replaced with a positive spirit of fulfillment and vitality that comes from the principles outlined in this book. What's true of the companies we love is true of the leaders we love. They are deeply admired for being passionate, smart, resilient, trustworthy, original, and humane—the same qualities we admire in people.

Joie de Vivre made it through that difficult time. But I had a health scare in late 2008, which woke me up to the fact that my new calling was to primarily be a writer and speaker. Of course, that was confusing to me, and everyone around me, as we thought I'd be the owner and CEO of my company for at least another 25 years. Ultimately, I sold Joie de Vivre, the brand and the management company, in mid-2010. But I kept ownership in much of the hotel real estate, and provided guidance to the new ownership team (led by John Pritzker of Geolo Capital, whose father started the Hyatt hotel chain). This gave me time to sort through my emotions after my heart literally stopped at age 47, which led me to write Emotional Equations.

In March 2013, I was approached by Brian Chesky, the CEO and cofounder of Airbnb, at the time a small start-up home-sharing company. He and some of the young execs had read Peak and were intrigued by how it might apply to Airbnb's business model. Brian asked if I wanted to “democratize hospitality,” which sounded pretty nifty to me. But I only wanted to do it part-time since I'd just launched a business, Fest300 (now part of Everfest), to share my passion for the world's best festivals. Not surprising, the part-time consulting gig turned into a full-time obsession and leadership role for this “retired” CEO. Fifteen hours a week became 15 hours a day. How many chances do you get to disrupt your favorite industry? For me it happened not just once—as a boutique hotelier long ago—but a second time, at the forefront of the sharing economy.

My initial title was Hospitality Guru, which in a few weeks morphed into Head of Global Hospitality and Strategy. Brian said he liked the way my mind worked strategically and also asked me to create a Learning and Development department. Over four years, I oversaw more than a half-dozen departments and key initiatives for the company before moving into my Strategic Advisor role—and back to blessed part-time status. But what a fascinating journey it's been! We weren't really called a hospitality company in early 2013, and we were thought of as a travel tech start-up with a design focus. Today, we offer more accommodations than the top three hotel companies in the world combined—Marriott (including their Starwood acquisition), Hilton, and Intercontinental—and our private market valuation has surpassed $30 billion.

Today, I also see pyramids on whiteboards all over Airbnb's headquarters and our more than 20 offices around the world. But I remember just four months into my tenure, when Brian asked me to lead a three-day retreat for Estaff—our dozen-person senior leadership team—and I introduced the principles of Peak to develop our 2014 strategic initiatives. It's been a true peak experience to see the business model I developed applied at such a deep level to a fast-growing, high-profile company playing on a global canvas. Airbnb was going to succeed whether I was there or not. But I do feel a certain joy and honor at how my contribution helped this fledgling and extremely talented leadership team earn Inc. magazine's Company of the Year cover story in December 2014, and Glassdoor's Best Places to Work award in December 2015. And, I do believe the underpinning of Peak's humane approach to business has helped Airbnb steer clear of some of the cultural, personality, and strategic challenges that have hurt the reputations of other sharing economy companies.

While it turned into a huge disruption in my life, I'm glad I said yes to Brian. Many hoteliers couldn't see Airbnb coming. But I recognized that Brian's investment in the company's culture, and the fact that home sharing was addressing an unrecognized need for travelers—living like a local affordably—meant Airbnb had the potential to go big. As I point out in Chapters Seven through Nine on the Customer Pyramid, established companies can miss innovation if they get too fixated at the base and address only the expectations of their core customers.

A more mobile populace leads to changes in lodging needs. There's a growing number of mostly Millennials choosing to be “digital nomads,” living parts of the year in places like Bali or Baja, and the rest of the year in cities such as Boston or Austin. These folks are less interested in being upwardly mobile and are, instead, outwardly mobile. Equipped with a laptop and a smartphone, a Wi-Fi connection and a coworking space, these freelancers, entrepreneurs, and other modern merchants are not typically weighed down by home or car ownership.

My Baby Boomer generation saw work and leisure as an “either/or” proposition. With an occasional sabbatical to moderate workaholism, the global nomad phenomenon is “both/and”—enjoy a great life while doing work on the road. Add in the “bleisure” trend, where business travelers tack on a few extra days of leisure to an interesting destination, and you see an upward trajectory in the extended-stay lodging market. Nearly 60 percent of Airbnb's room-night demand in many major metropolitan markets is guests staying a week or longer, whereas the average length of stay for most urban hotels is less than three days. Thinking about the expectations, desires, and unrecognized needs of these new kinds of travelers has helped Airbnb deliver a level of guest satisfaction that far exceeds the hotel industry average (based upon net promoter score as the common metric). This is part of the reason we've grown so quickly.

Over the past decade, I've been introduced to so many business leaders who are also “peakers.” What's been surprising is how universal this Peak model is, no matter the industry, geography, or culture of the company. Some might be surprised that investment bankers are also intrigued by this humanistic approach to business, yet Merrill Lynch has invited me to give eight speeches to their various employees and customers around the world.

But it's another investment bank, Houlihan Lokey, that woke me up to the biggest realization I've had about my Maslovian model since I wrote the book: the two lines that define the boundaries between the Survive, Success, and Transformation levels of the Employee, Customer, and Investor pyramids are not fixed. When I was leading a workshop for Houlihan Lokey's top leaders, one astutely pointed out that, depending upon the industry and the economy, the bottom of the pyramid that defines survival could represent 80 percent of the pyramid. For example, investment bankers are money-obsessed. So, the base of their employee pyramid takes huge precedence. But, interestingly enough, both Merrill Lynch and Houlihan Lokey execs have agreed that the next two levels of the pyramid (Recognition and Meaning), while thin in the world of investment banking, represent the differentiators for an employer. This is where loyalty is created with their slightly mercenary bankers. As one exec said to me, “Peak helped us see that many of our bankers are stuck at the success level of the pyramids, not seeing the disruptive transformation available at the peak.” I call this “the illusion of being ahead” that afflicts many established companies and execs, who are just coasting along based upon historical momentum.

A completely different company, on a completely different continent, reinforced the message of the movable lines in the employee pyramid. Liderman is one of the largest security firms in Latin America, with more than 12,000 security guards, mostly in Peru and Ecuador. Its average employee makes as much in a month as the Houlihan Lokey investment bankers make in an hour. Yet, Liderman CEO Javier Calvo Perez Badiola, who also calls himself the “guardian of the culture,” told me at a Peak seminar in South America that their employee pyramid is dominated by money as well, because their guards and their families are living paycheck to paycheck. But, just as with the investment bankers, Javier—who is one of the most Peak-focused execs I've ever met—recognizes that you create a unique, loyalty-driven culture higher up the pyramid. This is part of the reason his company is consistently ranked one of the best employers in Latin America. Conversely, in many nonprofit, governmental, or educational institutions, the money slice of the pyramid is very thin and the meaning at the top is what predominates. So, these new insights have proven to me just how adaptable the Peak model is to just about any institution.

In my travels, I've met many inspired business leaders—some at conferences, others in the cliffside hot springs at Big Sur's Esalen Institute, and even some at the annual Burning Man event in Nevada. Bill Linton is an inspired idealist and, for 40 years, has been a pragmatic entrepreneur growing his life sciences company, Promega, to approximately $400 million in annual sales with a reputation that is world-class in the biotechnology world.

Bill and I are birds of a feather. Because we're both “Burners” (those who enjoy making the Burning Man pilgrimage each year), and because we consider Maslow as so fundamental to how we see life and business. Bill explains, “In the early 1990s, Promega's board and management team started exploring our purpose and meaning of being in business. As a model that reflects a path of meaningful growth, we chose Maslow's hierarchy and began to develop our purpose with corporate ‘self-transcendence’ as our aspirational goal. It was exciting and helpful to discover Peak and its insights. All our corporate leaders received it. Chip provides an excellent resource in how a business can access and practice a way of operating that brings greater reward for all parties involved. We have put the concepts into practice throughout the organization for the past two decades with excellent outcomes.”1

Khalil Gibran said, “Work is love made visible.”2 So true. If you're on the path of living a calling and you're in a habitat that supports that path. Tragically, only a small percentage of the world can say that. So, I'd like you to consider a one-month trial of the following exercise based upon the classic question we ask each other as strangers. When someone asks, “What do you do?” answer not with your profession, job title, or company. Tell them what creates meaning for you. This gives people a window into your occupational soul and it may also prompt them to ask a deeper question of themselves.

Or, they may just think you're a crackpot when you answer like I do: “I am a crossing guard at the congested intersection of psychology and business,” or “I dispense wisdom and uncover blind spots,” or “I help people do the best work of their lives.” A doctor could answer: “I fix people,” or “I listen,” or “I help people heal themselves.” My friend and colleague Debra Amador DeLaRosa helps people cultivate their unique stories and says, “I am a Story Gardener.” And Vivian Quach, who I featured at the start of my 2010 TED speech and has been cleaning hotel rooms in my first hotel, The Phoenix, for more than 30 years says, “I am the peace of mind police.” Who are you?

Finally, I share the following letter from someone whose life has been positively affected by this book. Receiving these kinds of letters keeps me motivated to continue writing about my experiences in business and in life. Thanks, Gabe! My next book, Wisdom@Work: The Making of a Modern Elder celebrates what the young and not-so-young have to offer each other.

Dear Chip,

I know that you're a storyteller, so I hope you can take some time to read and enjoy this one. It's a little long, but I assure you it's worth it.

My first job in hospitality was running an elevator.

Despite being a college graduate, the only entry-level hotel job I could find was as a host of a rooftop venue at a new boutique hotel. Being last in the pecking order, every night it was my job to run the independent elevator that took guests up and down 27 floors to and from the hotel's popular rooftop.

I was extremely embarrassed by my job. I had entered the hospitality world because of my love for creating experiences for those around me, and despite already having success in the service industry and travel booking, here I was confined to a tiny space for hours at a time. Something had to change.

First, I timed each elevator trip. Thirty-two seconds. I began to practice different ways to introduce myself and create a routine of relaying the basic facts and information required before they reached the top, always leaving room for a joke or some improvisation. I'd even recommend drinks at the bar, views around the rooftop, and give them my own business card for table bookings. After a while, guests began asking for me instead of the hosts that were actually working the venue.

I'd made the most of my “elevator pitch,” but I had yet to focus on another opportunity: the way down. In fact, most of the time I spent in that elevator alone, so how could I take advantage of that time?

When I told my parents I'd found a job, I decided to hide some of the details from them (specifically the moving metal box), but they still knew I was at the bottom of the food chain. As a gift, my mom sent me a book that she said would help me once I got to where I wanted to go. The book was called Peak, and I would read it every trip down in that elevator a half a minute at a time before hiding it in the emergency compartment as the doors opened for the next guests to go up.

Because of Peak I began to see more and more value in my job as well as those around me in other departments of the hotel. I also began approaching relationships with coworkers and guests more genuinely, enhancing my network and accelerating my development as a leader. It also provided me with a level of confidence in my decision-making that would serve me well when I got my shot.

Over the next three-and-a-half years, I worked from the elevator to management. While a lot of my own personal motivation led to my success, it was your book that prepared me for when I got my shot and provided a context from which I could evaluate and contribute to the overall leadership of the venue and hotel. I also decided to return to school for my master's, focusing on customer service psychology and business management before joining an up and coming hospitality group in 2015. I have since left that job and have been traveling around the world and preparing for beginning the next chapter of my life, one that introduces self-actualization, or perhaps my own “joie de vivre.”

I hope you enjoyed the story and continue to influence young professionals and companies poised to impact the world. Oh, and I can't wait for that next book, either.

Best,

Gabe Huntting

Notes

1.

personal communication

2.

Gibran Kahlil, “On Work,”

The Prophet

(New York: Knopf, 1923).

Preface

Deep down I always knew that business could be done differently. I founded and grew my company, Joie de Vivre Hospitality, with this rebellious spirit. But it wasn't until I was rocked to my foundation with a desperate economic downturn that I was truly able to see the power of my principles.

Celebrated restaurateur Danny Meyer told me he wrote his book Setting the Table because it helped him move from the intuitive to the intentional in how he ran the Union Square Hospitality Group. Brazilian CEO Ricardo Semlar has said he wrote his books The Seven-Day Weekend and Maverick to address one of his director's questions about whether what works in practice for their company could also work in theory. I decided to write Peak because it allowed me to combine three of my greatest interests: writing, psychology, and business. Writing this book required me to reconcile how Joie de Vivre has successfully interpreted one of the most famous theories of human motivation into how we do business. But my learning was most profound when I discovered dozens of other peak-performing companies that have also consciously and unconsciously relied on Abraham Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. It wasn't just my little company that was fond of Abe's pyramid. Yet, taking all of this learning and turning it into a book was quite a task. Thankfully, at a very young age, I knew I wanted to be a writer when I grew up, so all the time spent researching and writing just helped connect me back to a lifelong aspiration. I guess that means I'm now grown up.

This book is about the miracle of human potential: employees living up to their full potential in the workplace, customers feeling the potential bliss associated with having their unrecognized needs met, and investors feeling fulfilled by seeing the potential of their capital leveraged. Celebrated author Fred Reichheld says, “The fundamental job of a leader is to be a role model, an exemplary partner whose primary goal is to help people grow to their fullest human potential.”1 Great leaders know how to tap into potential and actualize it into reality. My hope is that whether you are a start-up entrepreneur or in management at a Fortune 500 company, you will be able to use the theory in this book to maximize your own potential as well as the potential of those around you. Don't get discouraged if this theory feels a little foreign. At Joie de Vivre, we weren't perfect, either. I can't say we acted on this theory every day in every one of our more than 40 businesses, but the process of educating everyone in the company about these principles made a big difference in our lives.

I might have called this book How I Survived the Great Depression and Created a Great Company and Great Relationships Along the Way, but I don't think my publisher could have fit that on the cover. It seems trite to say that companies are just communities of relationships. But common sense suggests, and empirical studies show, those organizations that create deeper loyalty—with employees, customers, and investors—experience more sustained success. In this age of commoditization, one of the truly differentiating characteristics of leaders and companies is the quality and durability of the relationships they create. Peak (a much more succinct title) will help you create peak experiences with those you work with so that these flourishing relationships will help you sustain peak performance.

Part OneMaslow and Me

Chapter OneToward a Psychology of Business

If we want to answer the question, how tall can the human species grow, then obviously it is well to pick out the ones who are already tallest and study them. If we want to know how fast a human being can run, then it is no use to average out the speed of the population; it is far better to collect Olympic gold medal winners and see how well they can do. If we want to know the possibilities for spiritual growth, value growth, or moral development in human beings, then I maintain that we can learn by studying the most moral, ethical, or saintly people.

Abraham Maslow1

Pop.

That word conjures up some nostalgic images for me: my dad who doubled as my Little League coach, a style of music I couldn't get enough of, the Shasta Orange I used to drink by the six-pack.

At the end of 2000, as we were enjoying the second millennium celebration, the word pop had a new meaning to me: it was the sound of champagne flowing, of good times continuing to roll, of prosperity anointing me with a hero's halo.

I had a lot to be thankful for. My company, Joie de Vivre Hospitality, had grown into one of the three most prominent boutique hoteliers in the United States. My first book of any note, The Rebel Rules: Daring to Be Yourself in Business, which included a foreword from my demigod, Richard Branson, was hitting the shelves. And USA Today had just profiled me as one of 14 Americans, along with Julia Roberts and Michael Eisner, to be “watched” in 2001. Every indication was that my life, my company, and my budding career as an author were all heading in the right direction—up—and the New Year would be a welcome one. Little did I know that the real thing to watch in 2001 would be that I didn't jump off the Golden Gate Bridge.

I went from being a genius to an idiot in one short year. You see, all 20 of my company's unique hotels were in the San Francisco Bay Area. Yes, you can tell me all about the value of geographic diversification, but in the late 1990s, there was no better place, with the possible exception of Manhattan, to operate a hotel. I had learned long ago that a company can be product-line diverse or geographically diverse, but it's hard to be both. Rather than be a Holiday Inn with replicated product all over the world, we consciously chose the opposite strategy as we built our company. We would focus our growth in California and create what has become recognized as the most eclectic, creative, and handcrafted collection of hotels, lodges, restaurants, bars, and spas in a single geographic location.

But that pop I heard around New Year's was more than just champagne. It was also the sound of the bursting dot-com bubble. It was the pop heard around the world, but nowhere was it louder than in my own backyard. I won't bore you with the details, but even before the tragedy of 9/11 sent the worldwide travel industry into an unprecedented tailspin, San Francisco and Silicon Valley hotels were experiencing annualized double-digit revenue losses because of the high-tech flameout. Bay Area business leaders didn't want to admit that we were as addicted to electronics as Detroit is to cars or Houston to oil, but in 2001, during that first full year of the new millennium, we came to realize that we were going through withdrawal.

It turns out the millennium was sort of the midpoint of the seesaw. The Bay Area had partied for five good economic years in the last half of the 1990s. But just like if you drink heavily for five days approaching New Year's you might also suffer through a five-day hangover, our region experienced a comparable nausea in the first five years of the new millennium. That seesaw hit the ground really hard. My business, my confidence, and my self- worth all took a precipitous fall.

What do you say to a journalist who asks, “How does it feel to be the most vulnerable hotelier in America?” I knew I was feeling rotten, but I didn't realize my melancholy was being observed on a national stage. The reality is my company, after 15 years of rising to the top of the hospitality industry, was suddenly undercapitalized and overexposed in a world that had changed overnight. I never realized that after founding Joie de Vivre at age 26, and dedicating 15 years to building it, there was a risk I could lose everything. Most industry observers thought we were done for.

It wasn't just the dot-com meltdown or 9/11 that led to a truly troubled travel industry. A couple of wars, an outbreak of SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), and a very weak worldwide economy from 2001 to 2004 didn't help. It seems as if everyone wanted to stay close to home. The San Francisco Bay Area was ground zero for this great depression for American hoteliers. In the history of the United States since World War II, no hotel region in the country had ever experienced the percentage drop in revenues the Bay Area experienced in those first few years of the new millennium. And because Joie de Vivre operated more hotels in the region than any other hotelier, we faced a classic thrive-or-dive dilemma.

I remember sitting on the dock of my best friend Vanda's houseboat in Sausalito, facing the sparkling city of San Francisco across the bay on a crystal-clear morning. It was low tide, which exposed all of the mud and muck of the shoreline. It felt familiar: my business was at low tide. Vanda certainly knew it and, being the poet aficionado she is, she read me a line from a Mary Oliver poem, “Are you breathing just a little and calling it a life?”*

I was speechless. I'd been holding my breath ever since I'd heard the pop of the bubble bursting. I had a moment of clarity. This downturn was proving to be a true stress test for my business, but it was also a stress test for me personally. I'd been joking with my Joie de Vivre leadership team that we were becoming a faith-based organization. We truly believed this downturn wouldn't last forever, but with each passing quarter, things only got worse. The pressure made me feel like I was going to pop. I realized I needed to stop holding my breath. Speechless, yes—breathless, no.

A couple of days later, when I was experiencing a bit of malaise, I snuck into the Borders bookstore around the corner from Joie de Vivre's home office. I needed another Mary Oliver fix or some form of inspiration. A CEO in the poetry section of a downtown bookstore on a weekday afternoon? I felt like I should be wearing sunglasses and a disguise. Somehow I drifted over to the psychology section of the bookstore; maybe it had something to do with my mental state.

There among the stacks I came upon a section of books by one of the masters of twentieth-century psychology, Abraham Maslow. I started leafing through Toward a Psychology of Being, a book I'd enjoyed 20 years earlier in my introductory psychology class in college. Moments grew to minutes, which grew to hours as I hunkered down, sheepishly looking over my shoulder every once in a while to make sure no one was watching. I couldn't put the book down. Everything Maslow was saying made so much sense: the Hierarchy of Needs, self-actualization, peak experiences. In the midst of the crisis that was threatening my business, which was challenging me personally as I had not been challenged before, this stuff reminded me why I started my company.

When you name your company after a hard-to-pronounce, harder-to-spell, French phrase meaning “joy of life,” as I did, you must have different motivations than the typical Stanford MBA. The goal I set for myself just a few years out of Stanford was to create a workplace where I could not only seek joy from the day-to-day activities of my career but also help create it for both my employees and customers. I'd done a short stint at Morgan Stanley investment bank and realized that my aspiration in life was not to climb the typical corporate ladder. After deciding against a career in investment banking, I'd spent a couple of years in the rough-and-tumble world of commercial real estate construction and development and realized that spending all day negotiating through adversarial relationships wasn't my idea of a good time, either.

It was on my twenty-sixth birthday that I finished the business plan for Joie de Vivre. At that point, I'd become a tad disillusioned with the traditional business world and was considering a career as a screenwriter or massage therapist (I did training in both). Starting a boutique hotel company was my last option before I took an exit off the business superhighway. What inspired me about the hospitality world was that if we got our job right, we made people happy. And as a boutique hotelier, I could tap into my creativity to do things that I could never do in building an office tower. I remember telling an MBA friend back in 1987, when he was helping me paint my first hotel (I didn't have the budget to hire a professional painting contractor), that Joie de Vivre was my form of self-actualization (we'd both been exposed again to Maslow in a business school class called Interpersonal Dynamics, which all of us deridingly called “touchy-feely”).

Each day during the early part of 2002, when there seemed to be no limit to the depths the San Francisco hotel industry could fall, I would come home from work weary and a little battered and crack open another Maslow book. I even had the opportunity to read his personal journals from the last 10 years of his life. I started using some of his principles at work. I came to realize that my climb to the top wasn't going to be on a traditional corporate ladder; instead, it was to be on Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs Pyramid. During the next few months, I began to mentally compost this book—throwing everything into the bin I had experienced and everything I was learning—while giving my business mouth-to-mouth resuscitation based on Maslow's principles.

A Brief Primer on Maslow

A musician must make music, an artist must paint, a poet must write, if he is to be ultimately at peace with himself. What a man can be, he must be. This need we call self-actualization…. It refers to man's desire for self-fulfillment, namely to the tendency for him to become actually in what he is potentially: to become everything one is capable of becoming.

—Abraham Maslow2

Abraham Maslow is probably the most recognized and quoted psychologist in corporate universities and leadership books. In best-selling business books by legendary authors Stephen Covey, Peter Drucker, and Warren Bennis, you find many limited references to Maslow's seminal work. The influence of his thinking is everywhere. Author Jim Collins (Built to Last, Good to Great) wrote, “Imagine if you were to build organizations designed to allow the vast majority of people to self-actualize, to discover and draw upon their true talents and creative passions, and then commit to a relentless pursuit of those activities toward a pinnacle of excellence.”3

Maslow believed human beings had been sold short, especially by the traditional psychology community. Freud's perspective on the human psyche was a kind of “bungalow with a cellar,” with his main psychiatric focus being on people and their neuroses, which often came from childhood traumas. B. F. Skinner pioneered the idea of behaviorism in psychology, based on the premise that we could learn a lot about humans by studying lab rats (think of the bestseller Who Moved My Cheese?). Maslow came at this from a very different angle, focusing more on people's future than on their past. Instead of studying just people who were psychologically unhealthy, he began reading about history's acclaimed sages and saints to look for commonality in their outlook and behavior. Maslow focused on the “higher ceilings” of human nature rather than the basement cellar. Of course, this all made sense: in sports, in the arts, and in business, we study peak performers to understand how to improve our own performance. By recognizing that all humans have a higher nature, Maslow helped spawn the human potential movement in the 1960s and 1970s. And even the U.S. Army picked up on his theory when their internal Task Force Delta team turned Maslow's “What man can be, he must be” into the phrase “Be all you can be,” which became the advertising slogan in its recruiting campaign.

The foundation of Maslow's theory is his Hierarchy of Needs Pyramid, which presumes that “the human being is a wanting animal and rarely reaches a state of complete satisfaction except for a short time. As one desire is satisfied, another pops up to take its place…. A satisfied need is not a motivator of behavior.”4

Hierarchy of Needs Pyramid

Maslow believed that each of us has base needs for sleep, water, and food (physiological), and he suggested we focus in the direction of fulfilling our lowest unmet need at the time. As those needs are partially fulfilled, we move up the pyramid to higher needs for physical safety, affiliation or social connection, and esteem. At the top of the pyramid is self-actualization, a place where people have transient moments called peak experiences.

A peak experience—comparable to being “in the zone” or in the “flow”—is when what ought to be just is. Peak experiences are transcendental moments when everything just seems to fit together perfectly. They're very difficult to capture—just like you can't trap a rainbow in a jar. Maslow wrote, “They are moments of ecstasy which cannot be bought, cannot be guaranteed, cannot even be sought…but one can set up the conditions so that peak experiences are more likely, or one can perversely set up the conditions so that they are less likely.”5

This was pretty fascinating stuff. But as much as I searched for books on Maslow, I couldn't find one that applied his theory to the universal motivational truths that define our key relationships in the workplace.

Although I knew I wouldn't find a book that would say, “Here's how you can get out of your funk and create peak experiences at Joie de Vivre,” I began to wonder: if humans aspire to self-actualization, why couldn't companies, which are really just a collection of people, aspire to this peak also? Maslow wrote, “The person in the peak experience usually feels himself to be at the peak of his powers, using all of his capabilities at the best and fullest.…He is at his best, at concert pitch, the top of his form.”6 Why couldn't that same sentiment be applied to my company? What does a self-actualized company look like? And how could Joie de Vivre “set up the conditions so that peak experiences are more likely”?

I started studying Maslow even more deeply. I learned that this rebel with an IQ of 195 was elected to the presidency of the mainstream American Psychological Association in his latter years. His studies of exceptional individuals like Abraham Lincoln, Albert Einstein, and Eleanor Roosevelt helped him to realize that there was a “growing tip” of humanity who could prove to be role models for the rest of us. He called these individuals peakers as opposed to most people who were considered nonpeakers. The characteristics of these self-actualized people included creativity, flexibility, courage, willingness to make mistakes, openness, collegiality, and humility.

Maslow in the Workplace

In the summer of 1962, Abraham Maslow spent a few months at Non-Linear Systems (NLS), a digital voltmeter factory just north of San Diego, California. His goal was to see if the characteristics that defined the self-actualized person could also apply to a company. He saw industry as a “source of knowledge, replacing the laboratory…a new kind of life laboratory with going-on researches where I can confidently expect to learn much about standard problems of classical psychology, e.g., learning, motivation, emotion, thinking, acting, etc.”7 In essence, Maslow wanted to see if the science of the mind could be translated into the art of management.

Andrew Kay, the owner of NLS, relied heavily on Maslow's 1954 book Motivation and Personality to create a more productive and enlightened workplace. He believed, based on Maslow's theories, that employees satisfied their deeper social and esteem needs when they could witness the fruits of their labor. Kay noticed that his workers were more productive at the end of the assembly line, where finality of the assembly provided a sense of accomplishment. Kay dismantled the assembly lines, created small production teams that were self-managed, offered stock options, and created a post called the “vice president of innovation.” These teams were even allowed to choose the decor of their private workrooms—a pretty revolutionary approach during the era of the Organizational Man, more than 30 years before the first dot-coms sprouted.

Maslow was fascinated with how NLS used basic theories of human motivation and applied them in the workplace. He went on to publish a book on business called Eupsychian Management in 1965, but the inaccessible title doomed this effort, as did the fact that many of his ideas were probably ahead of their time (the book sold only 3,000 copies when it was first printed). Maslow's interest in business didn't wane, as he spent his last couple of years as the scholar-in-residence at the Saga Corporation on Sand Hill Road in Menlo Park, California, just off the Stanford University campus. (A couple of decades later, this street became the number one address for the world's leading venture capital firms.) I only wish Abe Maslow had lived to a proper age (he died in 1970 at 62 years old) because I might have had the opportunity to meet him: just eight years after he died, I was regularly running along Sand Hill Road as a freshman on the Stanford water polo team.

Although Maslow's impact in the workplace took decades to gain widespread acceptance, many business pioneers beyond Andrew Kay took his theories to heart. Charles Koch of Koch Industries got an authorization to reprint the long-forgotten Eupsychian Management for his senior executives as they built the country's second largest private company. Lee Ozley was a consultant to Harley-Davidson's president, Rich Teerlink, during the 1980s and 1990s, when the company was struggling to survive. Ozley had studied with Maslow as a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin and believed the key to Harley's renaissance was aligning the employees' intrinsic motivations with the needs and priorities of the company. Harley's reengineering of its company and its unique approach to creating a cult brand with its customers can be partially traced back to Maslow's theories. Senior leadership in diverse companies from Whole Foods Market to Apple to Pinterest also credit Maslow's influence with helping develop the foundational elements of how they operate their businesses.

Maslow's message struck a chord with many business leaders. In essence, he said that with humans, there's a qualitative difference between not being sick and feeling healthy or truly alive. This idea could be applied to companies, most of which fall into the middle ground of not sick but not truly alive.

Based on his Hierarchy of Needs, the solution for a company that wants to ascend up the healthy pyramid is not just to diminish the negative or to get too preoccupied with basic needs but instead to focus on aspirational needs. This idea is rather blasphemous for some. The tendency in psychology and in business has always been to focus on the deficits. Psychologists and business consultants look for what's broken and try to fix it. Yet, fixing it doesn't necessarily offer the opportunity for transformation to a more optimal state of being or productivity.

Taking Maslow to Heart

It seems natural that corporate transformation and personal transformation aren't all that different. In this era when more and more individuals have undertaken deep personal change striving for self-actualization, it's not surprising that this has also become the marching orders for many companies. Employees are looking for meaning. Customers are looking for a transforming experience. Investors are looking to make a difference with their investments. We often forget, especially in today's high-tech world, that a company is a collection of individuals. As my friend Deborah Stephens wrote in Maslow on Management (which helped to resuscitate Eupsychian Management), “Amid today's impressive technological innovations, business leaders sometimes forget that work is—at its core—a fundamental human endeavor.”8

As a guy who runs his company in the shadow of the iconic Transamerica Pyramid, it's only fitting that I would become so pyramid-obsessed. Maslow's pyramid offered me a way of rethinking my business at a time when the brutal travel economy demanded it. During my first 15 years in business, I'd found that having an organizing philosophy I could live and teach to my team helped drive Joie de Vivre to success. Best-selling author Malcolm Gladwell (The Tipping Point and Blink) told the New York Times that part of the reason for his books' successes is, “People are experience-rich and theory-poor…people who are busy doing things…don't have opportunities to collect and organize their experiences and make sense of them.”9 I came to realize that Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs would become my organizing structure for understanding the aspirational motivations in my workplace and in the marketplace. It would be the road map for the next chapter in my company's history.

Using Maslow as our inspiration, we created a new psychology of business based on not just meeting the tangible, foundational needs of our key stakeholders but, more importantly, focusing on their intangible, self-actualizing needs. I came to realize that creating peak experiences for our employees, customers, and investors fostered peak performance for my company. This book illustrates that new psychology of business and tells the story of how Joie de Vivre transcended its challenging situation during the first five years of the new millennium and not only survived but thrived. It's all about where you put your attention. Are you focused on the base or on the peak of the pyramid in your relationships with your employees, customers, and investors?

Whereas our biggest hotel competitors, who had much deeper pockets, experienced bankruptcies and lender defaults during the big hotel downturn of 2001–2004, Joie de Vivre grew market share by 20 percent, doubled revenues, launched our most successful hotel ever, was named one of the 10 best companies to work for in the Bay Area, and reduced its annualized employee turnover rate to one-third of the industry average. How is it that Joie de Vivre, seemingly left for dead during the worst hotel downturn in 60 years, avoided the fate of its peers and began the most successful period in